Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

S Nantha Balan, Azhahari Kamal Ramli, Ahmad Kamal Md Shahid JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: W-02-(IM)-1683-10-2023]

18 July 2025

Family Law: Divorce — Appeal against refusal to allow variation (item 1G) by husband for variation of order granting interim relief to wife — Variation application premised on grounds of misrepresentation by wife and material change in circumstances — Spousal maintenance used by wife to pay for legal fees — Whether Judge erred in finding that misrepresentation and change in circumstances not proven — Whether spousal maintenance could be used for legal fees during pendency of matrimonial proceedings

The appellant (husband) and the respondent (wife) were married on 3 July 1999. In September 2018 the wife petitioned for a divorce and sought interim relief. By an order of court dated 9 December 2019, the wife was granted various forms of relief which included provisions for the maintenance of the children of the marriage including daily expenses for food and dining, education, insurance, medical expenses and travelling. The husband applied to vary item 1A with regard to the employment of a driver, 1B with regard to the type of car to be provided, item 1D regarding the employment of a full-time domestic helper, and item 1G with regard to the spending limit of the wife's credit card. The application was premised on the ground of misrepresentation, mistake of fact or material change of circumstances. The husband argued that the wife had committed misrepresentation in that the wife had used the credit card to pay the legal fees in the divorce proceedings contrary to her ground in support of her application for interim relief, namely for spousal maintenance. The High Court Judge (HCJ) disagreed that there had been a misrepresentation of fact and held that the husband's objection for the spousal maintenance provisions to be utilised to pay the legal fees was untenable because there was no indication that the wife could not use the funds for that purpose. The HCJ was of the view inter alia that spousal maintenance was inherently subjective and depended on the individual needs of the applicant with the court exercising discretion in each case; and that unless expressly excluded from the order dated 9 December 2019, the wife's legal costs were included in the said order. The HCJ accordingly allowed the variations in respect of items 1A, 1B and 1D but disallowed the variation to item 1G. Hence the instant appeal. The husband submitted that the wife's unilateral use of the interim relief for legal costs constituted clear misrepresentation, misuse and/or misconduct tantamount to disobedience of an order of court and abuse of process; that the interim relief prayed for by the wife did not include provisions for legal costs, forensic expert consultation fees, savings in TNG cash e-wallet and/or financial trader funding and jewellery; and that such expenses did not constitute interim relief within the ambit of the order dated 9 December 2019. The wife in response submitted that it was not proven that there was any misrepresentation or material change in circumstances, and that she was entitled to pay the legal expenses from the interim maintenance provision. It was further argued the husband's filing of the application for variation on 26 June 2023 after a delay of 4 years was an afterthought on his part to 'cripple' her. The issues that arose for determination were whether the HCJ was correct in finding that the husband had failed to prove misrepresentation and change in the circumstances under s 83 of the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976 (LRA) and whether legal fees could fall within interim maintenance during the pendency of divorce proceedings.

Held (allowing the appeal):

(1) The wife's application for interim relief was confined only to maintaining her luxurious lifestyle and the order dated 9 December 2019 was based on her disclosure of her description of such lifestyle and her needs, and the interim relief was capped at RM30,000.00. The HCJ's failure to consider that fact when dealing with the variation application and basing her decision on the ground that except for medical expenses, there was no other exception attached to the interim maintenance order was an error that warranted appellate intervention. The wife's legal expenses, forensic expert consultant fees, savings in a TNG cash e-wallet and/or financial trader funding did not fall within the category of the wife's needs when the order dated 9 December 2019 was pronounced. In this regard, the said order was made due to the misrepresentation of the wife, albeit innocently. (paras 35-37)

(2) There were no provisions in the LRA that entitled the wife to claim for legal expenses in the maintenance order. The wife therefore should not use the matrimonial provisions for expenses/purposes not specified in her application. Instead, the wife should have applied for a variation of the order dated 9 December 2019 to incorporate payment of legal expenses as part of the interim relief. (paras 40 & 46)

Case(s) referred to:

ALJ v. ALK [2010] SGHC 255 (folld)

AQT v. AQT [2011] SGHC 138 (folld)

Clayton v. Clayton [2015] NZHC 550 (distd)

Gisela Gertrud Abe v. Tan Wee Kiat [1986] 1 MLRA 70 (refd)

Sim Thong Realty Sdn Bhd v. Teh Kim Dar [2003] 1 MLRA 272 (refd)

Sivajothi K Suppiah v. Kunathasan Chelliah [2006] 2 MLRH 173 (refd)

Tay Chong Yew & Anor v. Onn Kim Muah [2016] 2 MLRA 663 (refd)

Teo Chee Cheong v. Chiam Siew Moi [2025] 2 MLRA 1 (refd)

UFU (M.W) v. UFV [2017] SGHCF 23 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Contracts Act 1950, s 18

Family Proceedings Act 1980 [NZ], s 64(1), (2)(a)(iii)

Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976, ss 77, 78, 83, 86

Women's Charter 1961, s 119

Counsel:

For the appellant: Sumita Gnanarajah (Agnes Loo Tse Ching & Hirasini S Mahandran with her); M/s Chris Lim Su Heng

For the respondent: Vasanthi V Sathasivam (Subathra K Sathianathan & Darshana Araventhan with her); M/s K Sugu Associates

[For the High Court judgment, please refer to Yogitha Kishanchand Jethwani v. Ashvin Jethanand Valiram & Ors [2023] MLRHU 1874]

JUDGMENT

Azhahari Kamal Ramli JCA:

Introduction

[1] This is an appeal by the appellant, who is the husband (respondent in the High Court), against the decision of the learned High Court Judge (HCJ) in dismissing his application for a variation of the interim maintenance order dated 9 December 2019 in favour of the respondent/wife petitioner in the High Court.

[2] In this judgment, the appellant will be referred to as "the husband", and the respondent will be referred to as "the wife."

Background Facts

[3] Both the husband and wife were married on 3 July 1999. They are blessed with 2 children, a boy who was born on 9 August 2002 and a girl who was born on 14 December 2004.

[4] The husband is a shareholder, Director and an Executive Director of the Valiram Group, one of the largest retail empires for luxury and branded goods in South East Asia.

[5] After their marriage, both the wife and the husband lived at the husband's family home in Sentul where they resided until 2009 before moving to a condominium at a high-scale neighbourhood in Kuala Lumpur.

[6] During the marriage, the wife has been enjoying a luxurious lifestyle provided by the husband. Among others, she was provided with a chauffeur- driven car, full-time maid, club membership at the Royal Selangor Golf Club, supplementary credit cards with credit limit of between RM100,000.00 and RM250,000.00, overseas vacations, travelling on first class/business class for overseas vacation and expensive handbags, watches and dresses. The husband also had purchased a unit at St Regis where renovation costs for the unit were estimated around RM5,500,000.00.

[7] Over the years, their marital relationship deteriorated. The couple had frequent quarrels and conflicts. In October 2017, the husband left the condominium. The wife, however, remains.

[8] In September 2018, the wife commenced divorce proceedings by filing a divorce petition. Thereafter, the wife filed an application for interim relief. On 9 December 2019, the High Court granted her various forms of relief. The husband has been ordered to maintain the wife and the children of the marriage in the interim, pending the disposal of the divorce petition.

[9] Among others, item 1G of the order dated 9 December 2019 provides that:

"The Respondent provides the Petitioner with one (1) supplementary credit card with a credit limit of RM100,000.00 (the credit card) where the Petitioner's monthly usage is capped at RM30,000.00 each month save and except for medical expenses of the Petitioner not covered by the medical insurance and the OTP to be sent to the Petitioner's number directly."

[10] It must be noted that the order dated 9 December 2019 has also made provisions for maintenance for the children of the marriage, including daily expenses for food and dining, education, insurance, medical expenses and travelling.

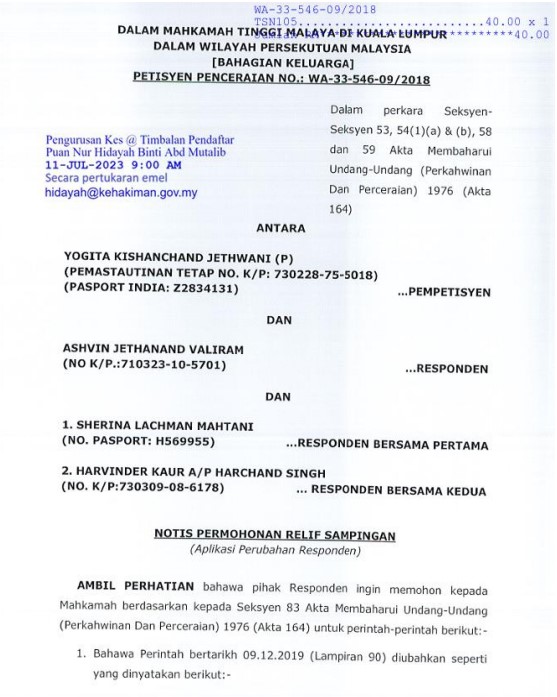

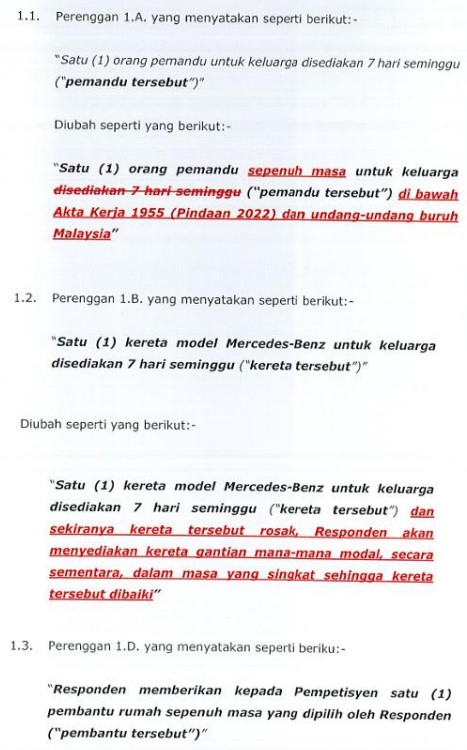

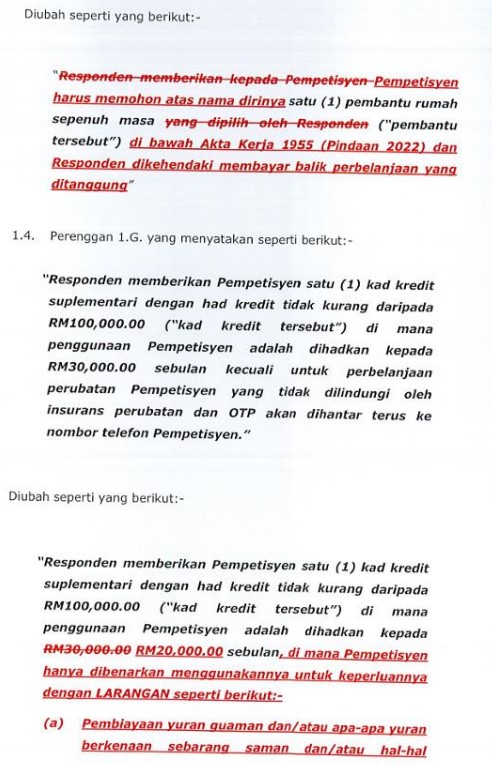

[11] The husband then filed an application to vary the High Court order dated 9 December 2019. The application was dated 26 June 2023. In that application, he sought to vary items 1A, 1B, 1D and 1G of the order dated 9 December 2019. The application was premised on the ground of misrepresentation, mistake of fact or material change of circumstances. For ease of reference, the application for variation is reproduced herewith:

[12] The husband's application was allowed in part on 16 November 2023. The learned HCJ only allowed variation in respect of items 1A (with regard to the employment of a driver), item 1B (with regard to the type of car to be provided) and item 1D (regarding the employment of a full-time domestic helper). The learned HCJ did not allow the variation regarding the spending limit of the credit cards ie, prayer 1.4 of the application relating to item 1G of the order dated 9 December 2019.

[13] Dissatisfied with the decision dated 16 November 2023, the husband appeals to this court against part of the order. The Notice of Appeal reads as follows:

Summary of the Decision of the High Court

[14] In essence, the purpose of this application is to stop the wife from using the money advanced to the wife for maintenance to be used to pay the legal costs in the divorce proceedings against the husband.

[15] Before the learned HCJ, the husband argued that the wife had committed misrepresentation when the usage of the credit card was not consistent with the grounds in support of the interim relief. It was submitted that the wife had used the credit card to pay legal fees in the divorce proceedings, contrary to her ground in support of the said application namely, for spousal maintenance. In this respect, the learned HCJ ruled that this contention was untenable because the maintenance order was specifically designated as spousal maintenance, irrespective of the children's need. It was also held that the order dated 9 December 2019 had already provided for child maintenance, reinforcing the distinction between spousal maintenance and child maintenance. When the court ordered that the wife's monthly expenses are capped at RM30,000.00, it is clear that the sum is not exclusively intended for the wife's daily expenses. Furthermore, there is no other exception attached to the order dated 9 December 2019 except for the medical expenses.

[16] The learned HCJ also found that the husband's objection to the spousal maintenance provisions to be utilised to pay the legal fees is also untenable because there is no indication that the wife cannot use the funds for that purpose. The learned HCJ opined that spousal maintenance is inherently subjective and depends on the individual needs of the applicant, with the court exercising discretion in each case.

[17] The learned HCJ disagreed with the husband that there was a misrepresentation of fact. There is no indication during the hearing of interim maintenance that the wife was not going to use the maintenance money for her legal fees. In fact, when the order of 9 December 2019 was made, it was foreseeable that the wife would incur legal expenses due to the intricate nature of the divorce petition. The learned HCJ also emphasised that any payment that the wife made from the RM30,000.00 spousal maintenance amount to pay for the legal expenses would inevitably reduce the funds available for the wife's other financial obligations.

[18] The learned HCJ also applied the New Zealand High Court case of Clayton v. Clayton [2015] NZHC 550, which ruled that a maintenance award can encompass the necessity for one party to cover accounting or legal expenses when there is ongoing litigation, facilitating the party's journey towards self- sufficiency. Hence, the learned HCJ was of the view that unless expressly excluded from the High Court order, the wife's legal costs are included in the 9 December 2019 order.

[19] The learned HCJ concluded that it became unmistakably clear that the husband was resolute in controlling the wife's expenditures, aiming to curtail her entitlement to spousal maintenance. The learned HCJ added that reducing the wife's interim spousal maintenance at this stage would be a stark contradiction to principles of justice and equity.

Summary Of The Submission Of Husband

[20] The husband argued that his application for variation is premised on the fact that the wife's application for interim relief did not include provisions for the impugned expenditure, ie, legal costs, forensic expert consultation fees, savings in TNG cash e-wallet and/or financial trader funding and jewellery. These expenses do not constitute interim relief within the ambit of the order dated 9 December 2019. It was argued that when considering the wife's application for interim relief, the order dated 9 December 2019 was premised on the wife's full and frank disclosure of the description of the marriage and her needs. In contrast, in the order dated 16 November 2023 (now appealed against), the learned HCJ interpreted item 1G of the order dated 9 December 2019 without making any reference to the wife's application and supporting affidavit for interim relief. This failure is a fundamental error on the part of the learned HCJ when considering the application to vary. In this respect, it was argued that there is no evidence that the wife's lifestyle during the tenure of the marriage to the husband included payment of legal costs, forensic expert consultation fees, savings in TNG cash e-wallet and/or financial trader funding. The order dated 9 December 2019, capping monthly interim relief at RM30,000.00, was intended solely for the wife's essential living expenses; hence, any deviation must necessarily constitute an abuse of the process and/ or material change in circumstances.

[21] The husband submitted that the discovery of the wife's unilateral use of the interim relief in June 2023 for legal costs and the contentious expenses without the husband's knowledge and to the husband's detriment constitutes clear misrepresentation, misuse and/or misconduct tantamount to disobedience of an order of court and abuse of process.

Summary Of The Submission Of The Wife

[22] The wife submits that the husband has failed to prove that there was any misrepresentation and whether there was any material change in circumstances. The learned HCJ was correct in finding that the order dated 9 December 2019 was specifically designated as spousal maintenance, irrespective of the children's needs. The husband has never given any money to the wife for her own savings throughout the course of the marriage. The husband was also fully aware that the wife had been financially dependent on him. Therefore, when the wife had to file the petition in the High Court, she did so on the basis of seeking justice for herself. It was submitted that these are pertinent considerations for the court to consider in determining the scope of item 1G of the order dated 9 December 2019; hence, the wife should be entitled to pay the legal expenses from the interim maintenance provision.

[23] It is also highlighted by the wife that item 1G of the order dated 9 December 2019 only made one exception with respect to the usage of the maintenance sum ie, in relation to the medical expenses which are not covered by the medical insurance. Furthermore, at the point of making the interim relief application, the wife had no knowledge that the trial of the divorce petition will be protracted up to almost 80 days and that she will have to use the maintenance to pay for the solicitor's fees.

[24] Contrary to the husband's submission that he only realised in June 2023 that the wife had been using the maintenance to pay the legal expenses, the wife submitted that the documentary evidence tendered in the court below shows that they were incurred from June 2021. The filing of the application for variation on 26 June 2023, after a delay of more than 4 years, shows that the application is an afterthought on the part of the husband designed to "cripple" her.

Analysis And Our Decision

[25] The memorandum of appeal contains 5 grounds of appeal. We have carefully examined the record of appeal and are of the view that the central issue in this appeal is whether the learned HCJ was correct in finding that the husband has failed to prove misrepresentation and change in the circumstances under s 83 of the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976 (the LRA).

[26] It is trite law that the court has the discretion in ordering a spouse to pay maintenance to his former spouse at any time from the commencement of the divorce proceedings. The order of maintenance may be ordered at any time from the filing of the divorce proceedings (pending disposal of the divorce proceedings), at the time or after the granting of decree of divorce or judicial separation and, in respect of a spouse who had been declared dead, after she is found. This power is provided for under s 77 of the LRA which provides:

"77. Power of Court to Order Maintenance of Spouse

(1) The Court may order a man to pay maintenance to his wife or former wife-

(a) during the course of any matrimonial proceedings;

(b) when granting or subsequent to the grant of a decree of divorce or judicial separation;

(c) if, after a decree declaring her presumed to be dead, she is found to be alive.

(2) The Court shall have corresponding power to order a woman to pay maintenance to her husband or former husband where he is incapacitated, wholly or partially, from earning a livelihood by reason of mental or physical injury or ill-health, and the court is satisfied that having regard to her means it is reasonable so to order."

[27] The power of the court is also extended to the recovery of arrears of maintenance owing to a particular spouse under s 86 of the LRA.

[28] The exercise of the court's discretion in determining the amount of maintenance to be paid is subject to the principle of "means and needs" of the parties regardless of the proportion such maintenance bears to the income of the parties ordered to pay the maintenance. However, this amount of maintenance to be paid shall have regard to the degree of responsibility which the court apportions to each party for the breakdown of the marriage. This is provided for under s 78 of the LRA which provides:

"Assessment of Maintenance

78. In determining the amount of any maintenance to be paid by a man to his wife or former wife or by a woman to her husband or former husband, the court shall base its assessment primarily on the means and needs of the parties, regardless of the proportion such maintenance bears to the income of the husband or wife as the case may be, but shall have regard to the degree of responsibility which the court apportions to each party for the breakdown of the marriage."

(see also the case of Tay Chong Yew & Anor v. Onn Kim Muah [2016] 2 MLRA 663)

[29] Notwithstanding s 78, the court is also empowered under s 83 of LRA to make variation to the order for maintenance. Section 83 reads as follows:

"Power of Court to Vary Orders for Maintenance

83. The court may at any time and from time to time vary, or rescind, any subsisting order for maintenance, whether secured or unsecured, on the application of the person in whose favour or of the person against whom the order was made, or in respect of secured maintenance, of the legal personal representatives of the latter, where it is satisfied that the order was based on any misrepresentation or mistake of fact or where there has been any material change in circumstances."

[30] Section 83 provides for a situation where the order for maintenance may be varied on the following grounds:

(a) misrepresentation;

(b) mistake of fact; or

(c) where there has been any material change in circumstances.

[31] We are of the view that, in determining whether the prerequisites in s 83 have been fulfilled, the court must go back to the time when the application for interim relief was made and to evaluate what are the means and needs of the parties when making the application. In this respect, the Supreme Court in Gisela Gertrud Abe v. Tan Wee Kiat [1986] 1 MLRA 70 held that:

"[4] When an application is made to the court to vary an existing order for maintenance, the proper approach is to start from the original order and see what changes financial or otherwise, have taken place since that date including any changes which the court is required to have regard to under s 78 as well as any increase or decrease in the means of either of the parties to the marriage and make adjustments roughly in proportion to the changes, if that is possible."

[32] We are minded of the fact that in Gisela Gertrud Abe (supra), the court was concerned with the issue of material change of circumstances. However, we are of the view that the approach adopted by the court in that case is equally applicable in our determination on the issue of misrepresentation or mistake of fact in the present case. We say this because the husband is now challenging the order dated 9 December 2019. As such the court must examine the fact that exists at the time of the filing of the application and decide whether the husband can prove misrepresentation, mistake of fact or change in material circumstances. Hence the facts that formed the basis for the said court order must be examined in this appeal to determine whether variation is justifiable.

[33] The LRA does not define the term 'misrepresentation'. Therefore, it is appropriate that reference to s 18 of the Contracts Act 1950 be made to render assistance in defining the said term. Section 18 provides:

"Misrepresentation" includes-

(a) the positive assertion, in a manner not warranted by the information of the person making it, of that which is not true, though he believes it to be true;

(b) any breach of duty which, without an intent to deceive, gives an advantage to the person committing it, or anyone claiming under him; and

(c) causing, however innocently, a party to an agreement to make a mistake as to the substance of the thing which is the subject of the agreement.

[34] In the case of Sim Thong Realty Sdn Bhd v. Teh Kim Dar [2003] 1 MLRA 272, it was held that:

"Now, it is trite that the expression 'misrepresentation' is merely descriptive of a false pre-contractual statement that induces a contract or other transaction. But this does not reflect the state of mind of the representor at the relevant time. The state of mind of the representor at the time he made the representation to the representee varies according to the circumstances of each case. It may be fraudulent. It may be negligent. Or it may be entirely innocent, that is to say, the product of a mind that is free of deceit and inadvertence (see Abdul Razak bin Datuk Abu Samah v. Shah Alam Properties Sdn Bhd). Put another way, misrepresentation is innocent 'where the representor believes his assertion to be true and consequently has no intention of deceiving the representee.'

(Cheshire & Fifoot, Law of Contract (6th edn). It is the particular state of mind of the representor that determines the nature of the remedy available to the representee. So, if the misrepresentation is made fraudulently, then the representee is entitled to rescission and all damages directly flowing from the fraudulent inducement."

[35] In support of her application for the interim maintenance order, the wife listed 13 items to be provided by the husband. Nowhere in her application did the wife ask for provision for expenses for the legal fees. Further, in her affidavit in support of her application for interim relief order (which runs into 46 pages with 179 paragraphs), the wife merely averred that she is so used to a luxurious lifestyle, including exhibiting her collection of expensive handbags and shoes, and insists that the husband should be ordered to pay for that lifestyle. It is worth mentioning that the affidavit of the wife also revealed that she needs RM2,713,414.60 per year (RM226,117.88 per month) to maintain her lifestyle. However, there is no indication in the affidavit that her lifestyle during the marriage included payment for legal costs, savings in a TNG cash e-wallet and/or financial trader funding. Also, there is no mention about the provision for any future legal expenses.

[36] It can be seen from the application and the affidavit in support that the wife's need at the time of making the application is only confined to maintaining her luxurious lifestyle. Hence, the order dated 9 December 2019 was made based on the wife's disclosure of her description of her luxurious lifestyle and her need. This explains why in the order dated 9 December 2019, the learned HCJ had capped the wife's interim relief at RM30,000.00 per month, save for medical expenses. Unfortunately, the learned HCJ did not consider this fact when dealing with the application for variation. The learned HCJ merely based her decision on the ground that there is no other exception attached to the interim maintenance order except for medical expenses. This, in our view is an appealable error which warrants our appellate intervention.

[37] We remind ourselves that the concept of innocent misrepresentation is accepted in our jurisdiction (see SimThong Realty Sdn Bhd (supra)). Hence, in the present case, when the wife has now used a portion of her interim maintenance provisions to pay for the legal expenses, forensic expert consultation fees, savings in a TNG cash e-wallet and/or financial trader funding, amounting to RM896,854.60 as at January 2025, these expenses do not fall within the category of the wife's need when the order dated 9 December 2019 was pronounced. Put another way, the wife did not consider these expenses as her needs when applying for the interim relief. In this regard, we are of the view that the order dated 9 December 2019 was made due to misrepresentation by the wife, albeit innocently.

[38] This brings us to the issue of whether spousal maintenance for the petitioner can be used for her legal fees during the pendency of the matrimonial proceedings. In other words, whether legal fees can fall within interim maintenance during the pendency of divorce proceedings.

[39] Generally, an order for maintenance is primarily a form of material provision that will enable an adult to live a normal life and a child is brought up properly (see Sivajothi K Suppiah v. Kunathasan Chelliah [2006] 2 MLRH 173), intended to cover the spouse's living expenses such as food, housing, clothing and medical care. These are considered basic needs to ensure the survival of the spouse during or after the disposal of the matrimonial proceedings.

[40] There is no provision in the LRA that entitles the wife to claim legal expenses in the maintenance order. In her judgment, the learned HCJ cited the case of Clayton v. Clayton [2015] NZHC 550 as an authority to support the proposition that a maintenance award can encompass the necessity for one party to cover accounting or legal expenses when there is an ongoing litigation, facilitating the party's journey towards self-sufficiency. In the light of Clayton v. Clayton (supra) the learned HCJ ruled that unless expressly excluded from the court order, the petitioner's legal costs should be included in the interim maintenance order. By this, the learned HCJ seems to have incorporated legal fees as one of the "need" considerations under s 83 of the LRA.

[41] Clayton's case (supra) was decided on the "clean break" principle in the final maintenance order. In his judgment, Courtney J states:

"[7] The provisions in ss 64 and 64A of the Family Proceedings Act 1980 for maintenance beyond the immediate period following the dissolution of a marriage or ending of a civil union or de facto partnership reflect the underlying "clean break" principle of that Act; a person's liability to maintain his or her former spouse or partner is usually expected to be temporary while the other person becomes self-sufficient."

[42] It is to be noted that, s 64(1) of the New Zealand's Family Proceedings Act 1980 (reproduced in Clayton's case judgment) provides that:

"(1) Subject to s 64A, after the dissolution of a marriage or civil union or, in the case of a de facto relationship, after the de facto partners cease to live together, each spouse, civil union partner, or de facto partner is liable to maintain the other spouse, civil union partner, or the de facto partner to the extent that such maintenance is necessary to meet the reasonable needs of the other spouse, civil union partner, or de facto partner, where the other spouse, civil union partner, or de facto partner cannot practicably meet the whole or any part of those needs because of any 1 or more of the circumstances specified in subsection (2).

(2) The circumstances referred to in subsection (1) are as follows:

(a) The ability of the spouses, civil union partners, or de facto partner, to become self-supporting, having regard to-

(i) the effect of the division of functions within the marriage or civil union or de facto relationship while the spouse, civil union partner, or de facto partner lives together:

(ii) the likely earning capacity of each spouse, civil union partner, or de facto partner:

(iii) any other relevant circumstances"

[Emphasis is ours]

[43] Obviously, Clayton's case (supra) is decided on a different provision of the law. Our section 83 of the LRA does not have similar provision as s 64 of the New Zealand Act. The New Zealand Act provides for situations where a spouse is liable to maintain the other spouse where the other spouse cannot practically meet the whole or any part of the other spouses' reasonable need. Unlike our s 83 of the LRA, s 64(2)(a)(iii) of the New Zealand Act is very broad which enables the court to consider any circumstances that have led the party seeking maintenance being unable to meet his or her reasonable needs.

[44] In this regard, the husband cited a Singapore case of UFU (M.W) v. UFV [2017] SGHCF 23 which cited the case of ALJ v. ALK [2010] SGHC 255 and AQT v. AQT [2011] SGHC 138 as follows:

105. The courts have generally accepted that legal fees are not to be deducted from the matrimonial pool. In ALJ v. ALK [2010] SGHC 255 Woo Bih Li J considered that "[i]f [a party] had incurred legal fees on the divorce and ancillary proceedings, he should have used his own assets to pay them first and not matrimonial assets" (at [431]). Similarly, in AQT v. AQT [2011] SGHC 138, Lai Siu Chiu J did not accept that the wife's legal fees for matrimonial proceedings could be deducted from the pool of assets. Lai J stated as follows:

It was highly unusual for the legal fees for these very matrimonial proceedings to be deducted from the pool of matrimonial assets. It would be an unwise precedent to allow parties to deduct their hefty legal costs from the pool of matrimonial assets. Whatever liability parties owe their solicitors for the matrimonial proceedings should be settled from their own share of the matrimonial assets after division. To deduct the legal fees from the joint pool of matrimonial assets during the proceedings would be to render any costs order the court made in the judgment largely nugatory.

[Emphasis Added]

[45] The Singapore cases referred to in the preceding paragraph are decided based on the provisions of their Women's Charter 1961. Section 119 thereof gives the court power to vary the order for maintenance on the ground of material change in circumstances. This provision is quite similar to our s 83 (except that misrepresentation and mistake of fact are not the ground for variation in the Singapore Act). We find that those authorities are highly persuasive. In this regard, we share the similar view taken by Justice Wong Kian Kheong in Teo Chee Cheong v. Chiam Siew Moi [2025] 2 MLRA 1 that Singapore cases should be preferred when this court is adjudicating a matrimonial matter (even though in that case, the court is concerned with the issue of division of matrimonial assets).

[46] Based on the above reasons, we are of the opinion that, the wife should not use the matrimonial provisions for expenses/purposes not specified in her application. This is also consistent with the rule of pleadings, in that parties are bound by their pleadings and the relief sought in the application. However, faced with the predicament as pleaded in her affidavit, the wife is not without any redress. It must be emphasised, that s 83 is applicable to both the wife or the husband. This is so based on the phrase "on the application of the person in whose favour or of the person against whom the order was made" used by the legislature in that provision. Hence, the wife should have made an application for the variation of the order dated 9 December 2019 to incorporate payment of legal expenses as part of the interim relief. A proper application should be made before such payments were made.

[47] For the aforesaid reasons, we are of the view that there is merit in this appeal. The learned HCJ has committed an appealable error when she dismissed prayer 1.4 of the husband's Notice of Application for Ancillary Relief dated 26 June 2023. The appeal is hereby allowed. The order of the learned HCJ for variation dated 16 November 2023 is set aside. We allow prayer 1.4 of the Notice of Application for Ancillary Relief dated 26 June 2023.

[48] However, we do not make any order for reimbursement of such payments made by the wife in contradiction to prayer 1G of the order dated 9 December 2019 as there is no provision for such relief under the LRA.

[49] Costs of RM15,000.00 to the husband subject to allocatur fee.