Federal Court, Putrajaya

Ahmad Terrirudin Mohd Salleh, Lee Swee Seng, Rhodzariah Bujang FCJJ

[Civil Appeal Nos: 02(i)-26-08-2024(W), 03-5-08-2024(W) & 03-6-08-2024(W)]

29 January 2026

Contract: Breach — Assessment of quantum — Appeal to Federal Court on assessment of quantum following liability judgment — Failure by joint-venture partner to remit maintenance fees — Common-law derivative action — Account and inquiry — Subsequent winding up of joint-venture company before completion of assessment — Whether events occurring after a liability judgment including winding up could limit the period of assessment — Whether winding up of injured party was a relevant intervening event reducing or terminating liability — Whether winding up constituted an unavoidable supervening event or an avoidable consequence of breach — Whether effect of winding up barred by issue estoppel or abuse of process at quantum stage — Whether operating costs and expenses had to be deducted to determine net profit — Whether Court of Appeal erred in refusing deductions by adopting an overly literal construction of liability judgment

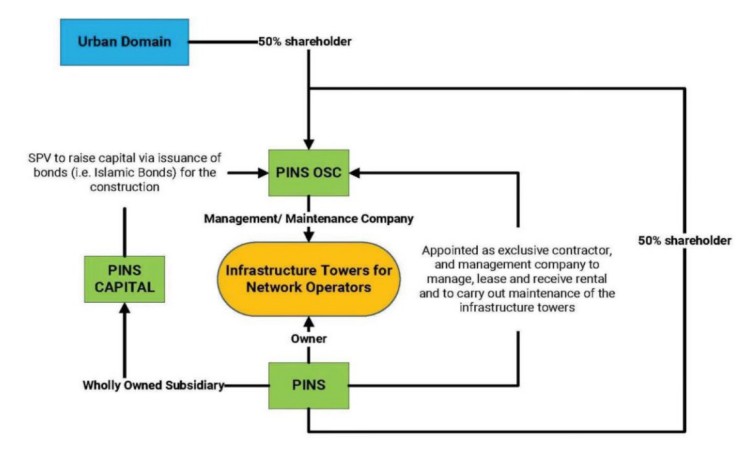

The appellant, Perak Integrated Network Services Sdn Bhd ("PINS"), and the 2nd respondent, Urban Domain Sdn Bhd ("UDSB"), were joint-venture partners in the 1st respondent, PINS OSC & Maintenance Services Sdn Bhd ("OSC"), in which PINS and UDSB each held a 50% shareholding. Pursuant to a Management Agreement and a First Supplemental Agreement dated 21 May 2007, OSC was appointed to construct, maintain and manage telecommunications towers,with PINS responsible for collecting rental proceeds from network operators and paying OSC a maintenance fee. Following PINS' failure to remit maintenance fees due to OSC, UDSB commenced a common-law derivative action on behalf of OSC against PINS. On 26 September 2013, the High Court entered a liability judgment in favour of OSC for breach of the agreements and ordered an account and inquiry to assess quantum, allowing only a limited counterclaim deduction for payments made by PINS to the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission. OSC was subsequently wound up on 27 October 2016 before the completion of the account and inquiry. In the quantum proceedings, disputes arose as to whether the assessment period should be cut off at the date of winding up and whether costs and expenses incurred in generating gross revenue should be deducted. The Court of Appeal restored the Senior Assistant Registrar's order extending the assessment period beyond the winding up date and held that further deductions were not permissible. PINS filed three appeals to the Federal Court from the decision of the Court of Appeal, all concerning quantum. The issues before the Federal Court were whether, in assessing quantum pursuant to a prior liability judgment, events occurring after judgment, including the winding up of the injured party, could limit the period of assessment; whether the winding up of OSC was a relevant intervening event for reducing or terminating PINS' liability and whether, on a proper construction of the liability judgment, the assessment of sums payable required deduction of operating costs and expenses beyond those expressly allowed, having regard to established compensatory principles and the governing contractual framework.

Held (allowing the appellant's appeals in part):

(1) The winding up of OSC on 27 October 2016 was a subsequent event occurring after the liability judgment and was not a relevant terminating event for limiting the period of assessment, as it would not have occurred but for PINS' breach and could not be relied upon by the defaulting party to reduce its liability. (paras 63 & 70)

(2) Given the bifurcation of liability and quantum, the effect of OSC's winding up was not finally determined at the liability stage, and raising it at the quantum stage did not constitute an abuse of process nor attract issue estoppel in the wider sense. (paras 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39 & 57)

(3) Unavoidable supervening events were distinguished from avoidable consequences flowing from the breach. OSC's winding up was an avoidable event contributed to by PINS' non-payment and was therefore irrelevant to reducing damages. (paras 58, 59, 60, 62, 63 & 64)

(4) However, regarding the interpretation of the liability judgment, the Court of Appeal had adopted an overly literal approach. A liability judgment must be interpreted consistently with established principles of law, the pleadings, the contractual scheme, and the compensatory principle, and not in a manner that would over-compensate the injured party or rewrite the parties' agreements. As the claim was for loss of profit and not gross revenue, expenses and costs that would have been incurred had the contract been performed had to be deducted to arrive at the proper quantum, consistent with compensatory principles and authority. (paras 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93 & 122)

Case(s) referred to:

Arnold v. National Westminster Bank Plc [1991] 2 AC 93 (refd)

Asia Commercial Finance (M) Berhad v. Kawal Teliti Sdn Bhd [1995] 1 MLRA 611 (refd)

Bunge SA v. Nidera BV [2015] 3 All ER 1082 (distd)

Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung v. Rayner And Keeler Ltd And Others (No 2) [1966] 2 All ER 536 (refd)

Chee Pok Choy & Ors v. Scotch Leasing Sdn Bhd [2001] 1 MLRA 98 (folld)

Golden Strait Corporation v. Nippon Yusen Kubishiki Kaisha [2007] 2 AC 353 (distd)

Henderson v. Henderson [1843] 3 Hare 99 (refd)

Hoban Steven Maurice Dixon & Anor v. Scanlon Graeme John & Ors [2007] 2 SLR(R) 770 (refd)

iVenture Card Ltd And Others v. Big Bus Singapore Sightseeing Pte Ltd And Others [2022] 1 SLR 302 (distd)

Johnson v. Gore Wood & Co [2001] 1 All ER 481 (refd)

Kerajaan Malaysia v. Mat Shuhaimi bin Shafiei [2018] 2 MLRA 185 (refd)

Lim v. Comcare [2019] 165 ALD 217 (refd)

Manoharan Malayalam v. Menteri Dalam Negeri Malaysia & Anor [2009] 1 MLRA 81 (refd)

Marl Jaya (M) Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Malaysia & Ors (Encl 50) [2017] MLRHU 848 (refd)

New Century Media Limited v. Mr Vladimir Mahkhlay [2013] EWHC 3556 (QB) (refd)

Newacres Sdn Bhd v. Sri Alam Sdn Bhd [2000] 1 MLRA 184 (refd)

Orji And Another v. Nagra And Another [2023] EWCA Civ 1289 (refd)

Rinota Construction Sdn Bhd v. Mascon Rinota Sdn Bhd & Ors [2021] 3 MLRA 647 (refd)

Sans Souci Ltd v. VRL Services Ltd [2012] UKPC 6 (refd)

Scott & English (M) Sdn Bhd v. Yung Chen Wood Industries Sdn Bhd [2018] 2 SSLR 81 (refd)

SPM Membrane Switch Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Negeri Selangor [2016] 1 MLRA 1 (folld)

Sujatha v. Prabhakaran [1988] 1 SLR (R) 631 (refd)

Superintendent of Pudu Prison & Ors v. Sim Kie Chon [1986] 1 MLRA 131 (refd)

Syarikat Sebati Sdn Bhd v. Pengarah Jabatan Perhutanan & Anor [2019] 2 MLRA 171 (refd)

Takako Sakao (f) v. Ng Pek Yuen (f) & Anor (No 2) [2009] 3 MLRA 92 (refd)

Tan Soo Bing & Ors v. Tan Kooi Fook [1996] 2 MLRA 164 (refd)

The "STX Mumbai" And Another Matter [2015] 5 SLR 1 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Companies Act 2016, ss 492, 493

Rules of Court 2012, O 43 r 2(1), O 56 r 1

Rules of the Federal Court 1995, r 137

Counsel:

For the appellant: Gopal Sreenevasan (Villie Nethi, Saw Wei Siang & Low Yun Hui with him); M/s Nethi & Saw

For the 1st respondent: Wilson Lim Mao Shen (Huam Wan Ying with him); M/s Wilson Lim

For the 2nd respondent: Bastian Vendargon (Leong Kwong Wah, Goik Kenwayne, Gene Vendargon, Sera Foong Chui-Yeng & Vincent Lim Seng Liang with him); M/s Dennis Nik & Wong

[For the Court of Appeal judgment, please refer to Urban Domain Sdn Bhd v. Perak Integrated Network Services Sdn Bhd & Other Appeals [2025] MLRAU 279]

JUDGMENT

Lee Swee Seng FCJ:

[1] The three related appeals before us, heard together, raise two interesting issues. One is whether the winding up of a joint-venture company, after it has obtained a liability judgment in a derivative action but before quantum is assessed, limits the quantum to the period ending on the winding up date ("the Subsequent Winding Up Issue").

[2] The other issue is whether when a judgment specified only an item to be deducted from the gross revenue of certain services rendered by the joint-venture company, as part of the counterclaim allowed by the Court in favour of the defendant, should the assessment of the quantum to be paid to the joint-venture company take into account the costs and expenses incurred by it in generating the gross revenue ("the Interpretation of Liability Judgment Issue").

[3] The plaintiff, Urban Domain Sdn Bhd ("UDSB") brought a common-law derivative action for and on behalf of a Joint-Venture Company ("JV Company") PINS OSC Maintenance Services Sdn Bhd ("OSC") as a nominal 1st Defendant ("D1") against its joint-venture partner Perak Integrated Network Services Sdn Bhd ("PINS") as the 2nd Defendant ("D2") for loss of profit arising out of a breach of a Management Agreement ("MA") and First Supplemental Agreement ("1st SMA"), collectively called "MAs". The derivative action arose because of the failure of PINS to pay OSC maintenance fees derived from the Operators in Group B under the MAs. PINS had, at its end, entered into a License Agreement with Operators in Group A to charge them License Fees for their use of the Infrastructure Projects, chiefly consisting of the Telecommunications Towers ("Towers").

[4] The derivative action was resorted to by the plaintiff, as the shareholding of both UDSB and PINS in the JV Company OSC, being equal, there was no way in which a resolution could be passed for OSC to bring an action to recover the amount not paid by PINS to OSC.

[5] There was also a claim against a 3rd Defendant who was a director of OSC and PINS for damages for breach of fiduciary duties in failing to claim for the maintenance fees due to OSC from PINS. The High Court had dismissed this claim, and as there was no appeal, the effective parties to these appeals are PINS as the appellant and UDSB as the 2nd Respondent ("R2") with OSC as the 1st Respondent ("R1"). As OSC is merely a nominal respondent, the respondent UDSB is the substantive respondent in these three appeals.

Before The High Court (Liability)

[6] The trial at the High Court was bifurcated into a finding of liability followed by quantum if liability was found. The Liability High Court gave its amended Liability Judgment on 26 September 2013 in favour of the plaintiff, having satisfied itself that there was a breach of the MAs when PINS refused to pay the maintenance fees to OSC for the Operators under Category B.

[7] The Liability High Court also allowed part of the counterclaim of PINS on OSC's failure to pay the Licensing Fee of Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission ("MCMC") to the extent of about RM3,224,904.10, inclusive of fines for late payment, which payment PINS had to pay to prevent its license with MCMC from being terminated. The appeal by PINS on Liability to the Court of Appeal was dismissed and so was its leave to appeal to the Federal Court.

Before The High Court (Quantum)

[8] Meanwhile the High Court ("Quantum") proceedings in the First Account and Inquiry were heard before the Senior Assistant Registrar ("SAR") and on 6 August 2021 she made an order for the production of various documents via the necessary affidavit by PINS to disclose the rental proceeds and other payments collected from the Operators in Group A and Group B ("the Telcos") from 21 May 2007 (the date of the MA) to the dates of the last Authorised Work Orders ("AWOs") for the 87 Towers. The Account and Inquiry was ordered under O 43 r 2(1) of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC 2012").

[9] The Towers were constructed by the JV Company under the terms of the MAs wherein it was stated that PINS was the company that had been awarded a Concession Contract by the Perak State Government through its designated entity to construct and maintain the towers. PINS then incorporated OSC with equal shareholding with a Shareholders Agreement governing their relationship and with terms on board representation which are not relevant for the present appeal. The parties to the MAs are UDSB, PINS, OSC, together with PINS' wholly-owned subsidiary PINS Capital Sdn Bhd ("PINS Capital"), which was responsible for raising financing for the Concession Works contracted out to OSC.

[10] The relationship of the companies to one another is well captured in para 2.3.3 of the Expert Report filed with the Quantum High Court:

[11] There were also other agreements entered into, such as a Deed of Assignment by PINS to assign to PINS Capital the Rental Proceeds from the Telcos for the Repayment Sum to be made for the financing, leaving a "Balance Sum" under the MAs and it was only after deduction of what was termed as Priority Payments that the "balance of the Balance Sum" shall be held by OSC with OSC taking thereafter 20% of Rental Proceeds as its Maintenance Fees.

[12] Both UDSB and PINS, being dissatisfied with the Registrar's order, appealed to the Judge in Chambers ("Time-Period Quantum Judge"). The Time-Period Quantum Judge on 10 June 2022 allowed the appeal of PINS in part and dismissed the appeal of UDSB. The order of the Registrar was varied and amended to read as follows, with the remaining orders left intact in the High Court Time-Period Quantum Order:

"An Order that the 2nd Defendant do render to the Plaintiff the true account and full information of all monies and license fees (the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments) received by the 2nd Defendant from all the Group A Operators and Group B Operators for the 87 Towers between 21 May 2007 (the date of the Management Agreement) and 27 October 2016, being the date of the winding up Order made pursuant to Winding Up Petition No WA-2BNCC-724-08/2016."

Before The Court of Appeal ("Quantum")

[13] UDSB filed 2 appeals to the Court of Appeal with respect to the High Court Time-Period Quantum Order under O 56 r 1 of the ROC 2012; one for dismissing its appeal and another for allowing PINS' appeal. The Court of Appeal allowed, on 7 December 2023, UDSB's appeals and set aside the Order of the High Court (Time-Period Quantum Judge) of 10 June 2022 and made the following order:

"3. The Order of the Senior Assistant Registrar dated 6 August 2021 is restored ("SAR Order"), and Minute 1 of the SAR Order is amended as follows:

3. 1. An Order that the Respondent herein do render to the Appellant the true account and full information of all monies and license fees (the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments) received by the Respondent from all the Group A Operators and Group B Operators for the 87 Towers for the Extended License Period (all therein the Amended Judgment dated 26 September 2013 and all herein this Affidavit in Support affirmed by Azrina binti Mohammad Aziz on 23 June 2017).

4. The matter is remitted to the High Court for further account and inquiry pursuant to para 3 above, in respect of the liability period not covered in the Quantum Order; and

5. Costs of RM20,000.00 to be paid to the Appellant, subject to allocator."

[Emphasis Added]

[14] The Court of Appeal (Quantum) held that the subsequent winding up of UDSB on 27 October 2016, after the Liability Judgment and before the Assessment, did not in any way affect the period for which PINS was held liable as the winding up was not relevant. Moreover, PINS was estopped from raising this issue of winding up at the Quantum stage when the winding up that happened some 3 years after the Liability Judgment was a matter known to the appellant PINS in the Liability Appeals to the Court of Appeal and the leave application to the Federal Court but the issue of winding up having the effect of being a cutting-off date for the Liability Period was not raised.

[15] The Court of Appeal also held that to take into account the subsequent winding up of OSC would be to deviate from the terms of the Liability Judgment and additionally it was PINS that contributed towards the winding up of OSC for a paltry sum of some RM60,000.00 being the amount of tax owing to the petitioning creditor the Director General of the Inland Revenue of Malaysia in that it failed to pay OSC the Maintenance Fees due to OSC and as such it cannot take advantage of its own breach to derive a benefit from it.

[16] The Court of Appeal had ordered the Period of Assessment to be until the "Extended License Period" which was introduced by the 2016 Supplementary License Agreement ("SLA") of 1 January 2016, which, like the winding up event, happened some 3 years after the Liability Judgment dated 26 September 2013 and some 4 years before the Liability Appeal in 2020.

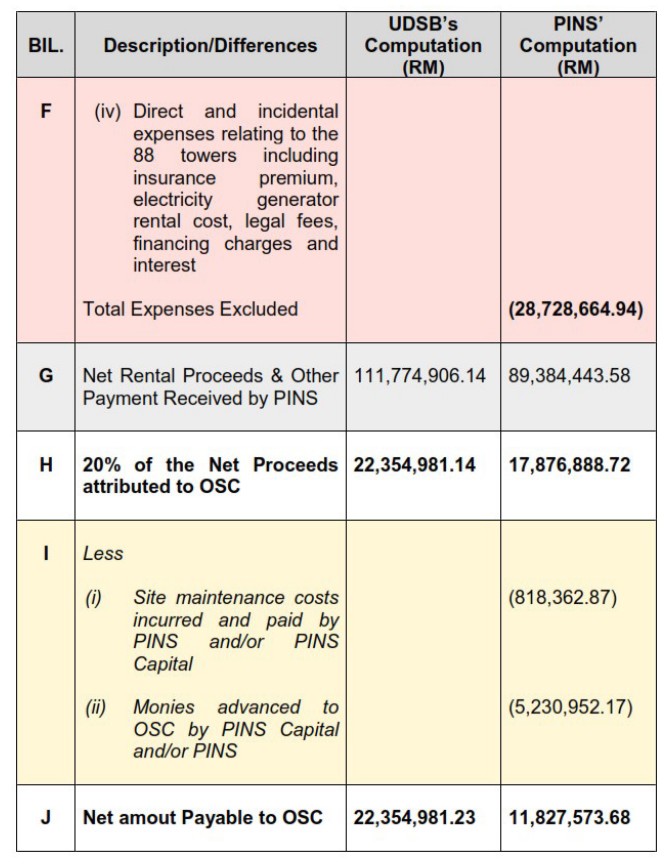

[17] It needs to be stated that there was also another appeal heard in PINS' appeal from the decision of the High Court (Assessment of Quantum) for by that time the High Court Assessment of Quantum Judge had already assessed the quantum based on the decision of the Time-Period Quantum Judge that decided the cut-off date of the assessment should be the date of the winding up. The Assessment of Quantum Judge had not allowed any deductions from the Rental Proceeds collected from the Telcos other than the amount allowed in the counterclaim of PINS for the MCMC fees and fines.

[18] The High Court Assessment of Quantum Judge assessed the quantum of the Maintenance Fee payable by PINS to OSC to be RM22,354,981.23 by order of the Court dated 20 February 2023 ("High Court Assessment of Quantum Order 1").

[19] The Court of Appeal further held that the Assessment of Quantum Judge had assessed the Quantum based on the terms of the Liability Judgment and as appeal to the Court of Appeal on the Liability Judgment was dismissed with further leave to appeal to the Federal Court being dismissed as well, it was too late to raise the issue of other deductions representing the costs and expenses incurred by OSC in generating the gross revenue. Any ambiguity on the Liability Judgment should have been raised in the Liability Appeal and not the Quantum Appeal, which was strictly confined to the exercise of determining Quantum from the clear words of the Liability Judgment.

In The Federal Court

[20] PINS filed 3 appeals to the Federal Court from the decision of the Court of Appeal (Quantum); 2 arising from the effect of the winding up on the Period of Liability and 1 on the correct interpretation of the Liability Judgment of the High Court.

[21] These 3 interconnected appeals filed by PINS before the Federal Court, all concerning Quantum, are as follows:

(a) Civil Appeal No 03-5-08/2024(W) ("Appeal 5");

(b) Civil Appeal No 03-6-08/2024(W) ("Appeal 6"); and

(c) Civil Appeal No 02(i)-26-08/2024(W) ("Appeal 26")

[22] Appeals 5 and 6 both arose from the Account and Inquiry before the SAR where on appeal from the SAR's order, the Time-Period Quantum Judge determined the applicable Time-Period for which OSC is entitled to receive the Maintenance Fee from PINS with the only difference being that Appeal 5 is PINS' appeal to the Time-Period Quantum Judge in Chambers which appeal was allowed but reversed by the Court of Appeal. Appeal 6 by PINS arose from UDSB's appeal, which was dismissed by the Time-Period Quantum Judge in Chambers, and which the Court of Appeal allowed.

[23] Appeal 26 arose from the Account and Inquiry by the Assessment of Quantum Judge which decision in the Assessment of Quantum O 1 was that costs and expenses were disallowed from being deducted in order to arrive at the amount to be paid by PINS to OSC. PINS' appeal to the Court of Appeal was dismissed.

[24] The question of law allowed by the Federal Court in respect of Appeals 5 and 6 is as follows:

"(1) Whether a Court in assessing quantum should take into account events occurring after the date of the breach of contract and/or the date of the Order for assessment, including a terminating event that would reduce or eliminate loss, having regard to Golden Strait Corporation v. Nippon Yusen Kubishiki Kaisha [2007] 2 AC 353, Bunge SA v. Nidera BV [2015] 3 All ER 1082, The "STX Mumbai" And Another Matter [2015] 5 SLR 1 and iVenture Card Ltd And Others v. Big Bus Singapore Sightseeing Pte Ltd And Others [2022] 1 SLR 302?"

[25] The legal questions allowed by the Federal Court in respect of Appeal 26 are as follows:

"(1) Whether, in construing an Order of Court, reference should be had to the background of the case, the pleadings and the grounds of judgment, having regard to Newacres Sdn Bhd v. Sri Alam Sdn Bhd [2000] 1 MLRA 184 or whether construing an Order of Court requires the application of established principles of law and practice other than those merely relating to construction, having regard to Sujatha v. Prabhakaran Nair [1988] 1 SLR(R) 631 and Hoban Steven Maurice Dixon & Anor v. Scanlon Graeme John & Ors [2007] 2 SLR(R) 770?; and

(2) Whether the proposition in SPM Membrane Switch Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Negeri Selangor [2016] 1 MLRA 1 that in an assessment of damages, expenses and costs are to be deducted, also applies to an account of profits for a breach of contract or otherwise?"

[26] The parties shall be referred to by their acronyms The appellant being PINS; OSC being the nominal respondent R1 in whose favour the derivative action was brought by R2 UDSB, the substantive respondent in the three appeals before us.

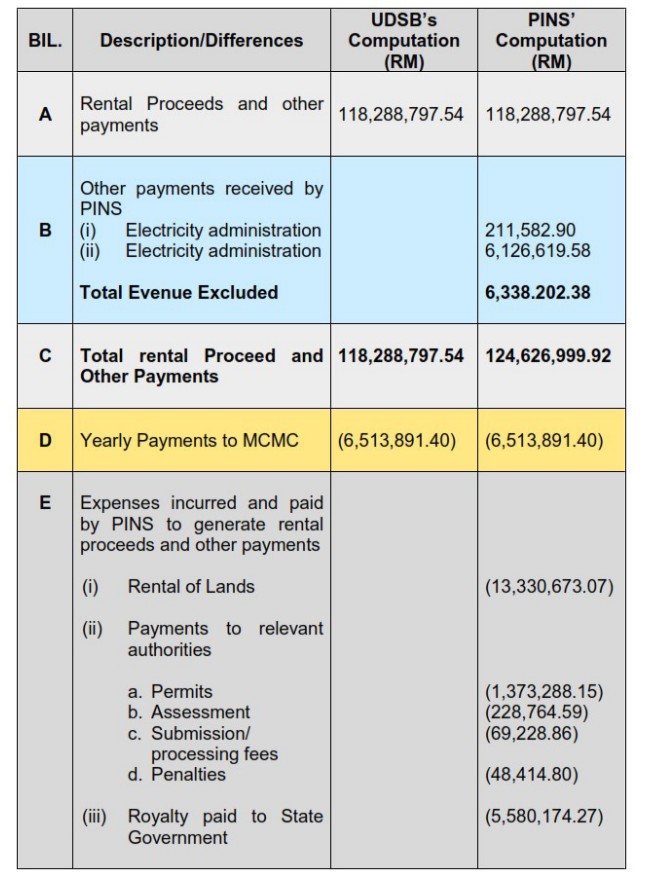

[27] Our task in unravelling the issues that have come to plague the parties since the Liability Judgment of 2013 was made more manageable in that PINS had candidly disclosed in its learned counsel's written submission at para 52 that the figures ascribed to each category of expenses are not in dispute — rather, the dispute centres on whether these categories of costs and expenses incurred should be deducted from the gross revenue of OSC ie the Maintenance Fee.

[28] That relieves the Court from being detained by the minutiae of massive items for each category of costs and expenses, not to mention the usual challenge on methodology in expert reports with its attendant assumptions, presumptions and projections and the application of the Discounted Cash Flow Method in the time-value of money realised now though realistically to be received only in the future until the expiry of the Extended License Period in 2037.

Whether Res Judicata And Estoppel Would Apply To Prevent The Appellant From Raising The Issue Of OSC's Winding Up Which Happened After The Liability Judgment As A Subsequent Intervening Event Which Limits The Period Of Assessment Of Quantum Up To The Date Of Winding Up ("The Subsequent Winding Up Issue")

[29] The fact of the winding up of OSC on 27 October 2016 is not disputed. It was an event that took place some 3 years after the Liability Judgment and before the assessment exercise. What is in dispute is the consequence of the winding up of OSC on the assessment of the compensation sum to be paid by PINS to OSC.

[30] UDSB argued that since the fact of winding up was known to PINS when the Liability Appeal was heard in the Court of Appeal and when the Leave Application to the Federal Court was dismissed, but that fact was not raised or argued, then PINS is estopped from raising it in the Quantum Appeals in the High Court and the Court of Appeal and now before the Federal Court.

[31] With respect, it cannot be said that the winding up was a pure Liability Issue. It is primarily an event that took place after the Liability Judgment and before the Assessment of Quantum Judgment 1. If the trial had proceeded with liability and assessment of the quantum together and not bifurcated, OSC would have been allowed to raise this issue on appeal, as there would have been only one appeal, on both liability and quantum.

[32] Moreover, the effect of the winding up on the Assessment of Quantum to be paid is generally a pure question of law which comes into acute focus when the assessment exercise to determine the Quantum is undertaken, for then the issue would be whether the Assessment should end at that winding up event or at the last AWO under the MAs. The Liability Judgment remains as it is and the only issue is when assessing Quantum, should the Time-Period Quantum Judge take the event of winding up of OSC into account.

[33] The issue of whether a winding up of the party in whose favour judgment had been given would be a liability issue if it is considered from the perspective of whether liability would cease upon the winding up of that party. However, it would be a case of pure interpretation on whether, in law, the subsequent event of a winding up has any effect on the Liability Judgment. That same issue affecting Liability would also have an effect on Quantum if the Assessment of Quantum is only up to the date of winding up.

[34] With respect, it would be more helpful and relevant to ask the question whether the winding up is a subsequent event that happened after the Liability Judgment had been entered, and not so much whether it ought to have been raised in the Liability Appeal and too late to be raised in the Quantum Appeal. The subsequent event of the winding up straddles both the Liability Judgment, where interpretation is concerned and the Quantum Judgment where an Assessment of Quantum has to be made with the Liability Judgment remaining intact. One does not have to be perturbed as to whether the subsequent winding up is primarily or particularly a liability issue, so long as its pervasive effect is said to be continuing at the point of Assessment of Quantum.

[35] As the respondent OSC would have every opportunity to resist the stand taken by the appellant PINS, there cannot be any serious prejudice suffered. A procedural point on appeal should not be over technical as walking a tight rope, such that to lose one's balance in a misstep would plunge one into the dark and bottomless abyss! Whilst many things are either black or white, there are some that are shades of grey.

[36] This is not a case where the issue of the effect of winding up on a Liability Judgment had been argued when the Liability Appeals were heard and the matter decided upon by the Court. It was raised for the first time during the Quantum stage before the Time-Period Quantum Judge. As the trial was bifurcated, it is not so much that the ship has sailed but that one may still catch the second ship before it sets sail.

[37] Res judicata means that a matter that had been adjudged with precision and finality would create an estoppel per rem judicatum such that the matter cannot be reopened for a fresh litigation or argument with the hope that the result may be different. See the locus classicus in the Supreme Court's case of Asia Commercial Finance (M) Berhad v. Kawal Teliti Sdn Bhd [1995] 1 MLRA 611.

[38] The res judicata referred to here is not a cause of action estoppel but rather an issue estoppel matter. With respect to issue estoppel, one needs to distinguish between issue estoppel in a narrow sense which would apply to issues actually decided by the Court in previous proceedings in which case the matter is res and it would not be allowed to be relitigated again, as there must be finality and an end to litigation on the same issue.

[39] Here, what is at stake is not issue estoppel in the narrow sense, as it is accepted that neither party brought up at the Liability Appeals the issue of the subsequent event of winding up of OSC having an effect on the Time-Period for which the Quantum is to be assessed. Instead, what is being argued is that of issue estoppel in the wider sense, in that an issue that could and should have been brought up and argued was not so done and so there was no decision on the issue.

[40] When applied in that wider sense and having its roots in equity, the test is whether its application would cause any serious prejudice to the party objecting to the issue being argued now, when it could have been argued before. The Court would have to look at the justice of the case and discern if the failure to raise the issue earlier would be an abuse of the court's process and balancing against that, the principle of a party not pursuing its claims or issues in instalments.

[41] The genesis of the doctrine of res judicata is traceable to its source in Henderson v. Henderson [1843] 3 Hare 99 at p 115 where Sir James Wigram V-C stated the proposition as follows:

"...where a given matter becomes the subject of litigation in, and of adjudication by, a court of competent jurisdiction, the court requires the parties to that litigation to bring forward their whole case, and will not (except under special circumstances) permit that same parties to open the same subject of litigation in respect of matters which might have been brought forward as part of the subject in contest, but which was not brought forward, only because they have from negligence, inadvertence, or even accident, omitted part of their case. The plea of res judicata applies, except in special cases, not only to points upon which the court was actually required by the parties to form an opinion and pronounce a judgment, but to every point which properly belonged to the subject of litigation and which the parties exercising reasonable diligence, might have brought forward at the time."

[Emphasis Added]

[42] The House of Lords in Johnson v. Gore Wood & Co [2001] 1 All ER 481 at p 499, [2002] 2 AC 1,30H-131F clarified that a strict interpretation of Henderson v. Henderson was too dogmatic an approach to be taken and that what was required was a broad merits-based judgment. The crucial question is whether, in all the circumstances, a party is misusing or abusing the court's process by seeking to raise the issue which could have been raised before. The approach is to ask if the failure to raise the issue earlier could be excused or justified by special circumstances. Lord Bingham explained as follows:

"The underlying public interest is the same: that there should be finality in litigation and that a party should not be twice vexed in the same matter. This public interest is reinforced by the public interest in the current emphasis on efficiency and economy in the conduct of litigation, in the interests of the parties and the public as a whole. The bringing of a claim or the raising of a defence in later proceedings, may, without more, amount to abuse if the court is satisfied (the onus being on the party alleging abuse) that the claim or defence should have been raised in the earlier proceedings if it was to be raised at all. It is, however, wrong to hold that because a matter could have been raised in earlier proceedings it should have been, so as to render the raising of it in later proceedings necessarily abusive. That is to adopt too dogmatic an approach to what should in my opinion be a broad, merits-based judgment which takes account of the public and private interests involved and also takes account of all the facts of the case, focusing attention on the crucial question whether, in all the circumstances, a party is misusing or abusing the process of the court by seeking to raise before it the issue which could have been raised before... it is in my view preferable to ask whether in all the circumstances a party's conduct is an abuse than to ask whether the conduct is an abuse and then, if it is, to ask whether the abuse is excused or justified by special circumstances."

[Emphasis Added]

[43] More recently, the UK Court of Appeal in Orji And Another v. Nagra And Another [2023] EWCA Civ 1289 cautioned with respect to the rule in Henderson v. Henderson (supra) as follows:

"47.... But it is crucial to remember that, whenever it arises, the rule in Henderson v. Henderson requires a previous determination by the court. As Lord Hobhouse put it in In Re Norris [2001] UKHL 34 at para 26: "It will be a rare case where the litigation of an issue which has not previously been decided between the same parties or their privies will amount to an abuse of process" (emphasis supplied). More recently, Nugee LJ reiterated in Wilson and Another v. McNamara and Others [2022] EWHC 243 (Ch) at [57], by reference to Henderson v. Henderson itself, that "the principle does not arise if there has not been a previous adjudication" by the court."

[Emphasis Added]

[44] Such an approach was already taken by our apex court in the Supreme Court case of Superintendent of Pudu Prison & Ors v. Sim Kie Chon [1986] 1 MLRA 131, at p 135, where Abdoolcader SCJ recognised that "the plea of res judicata applies, except perhaps where special circumstances may conceivably arise of sufficient merit to exclude its operation...".

[45] Later in Chee Pok Choy & Ors v. Scotch Leasing Sdn Bhd [2001] 1 MLRA 98, at pp 103-104, Gopal Sri Ram JCA (later FCJ), found support in the decisions of the UK House of Lords in Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung v. Rayner and Keeler Ltd and Others (No 2) [1966] 2 All ER 536, Arnold v. National Westminster Bank Plc [1991] 2 AC 93, and Johnson v. Gore Wood & Co (supra) to explicitly state the exception to res judicata as follows:

"... there is a dimension to the doctrine of res judicata that is not always appreciated. It is this. Since the doctrine (whether in its narrow or broader sense) is designed to achieve justice, a court may decline to apply it where to do so would lead to an unjust result. And there is respectable authority in support of the view I have just expressed.

...

On the authorities discussed thus far, the principle comes to this. Whether res judicata in the wider sense should be permitted to bar a claim is a matter that is to be determined on the facts of each case, always having regard to where the justice of the individual and particular case lies."

[Emphasis Added]

[46] Likewise, the Federal Court in Manoharan Malayalam v. Menteri Dalam Negeri Malaysia & Anor [2009] 1 MLRA 81 at para 17 reiterated that it does "... recognize the fact that there would be exceptional cases where matters which should have been raised were not, but when raised in subsequent proceedings would not amount to an abuse of process." This approach has been adopted by our Federal Court in Kerajaan Malaysia v. Mat Shuhaimi bin Shafiei [2018] 2 MLRA 185 at para [44].

[47] Our law has moved beyond the narrow exceptions of fraud and unavailability of fresh evidence enunciated in Federal Court case of Scott & English (M) Sdn Bhd v. Yung Chen Wood Industries Sdn Bhd [2018] 2 SSLR 81 at para 20 and later in Syarikat Sebati Sdn Bhd v. Pengarah Jabatan Perhutanan & Anor [2019] 2 MLRA 171, where at para 43 it was held:

"It is clear however from decided cases that the circumstances alluded to by the Court of Appeal (ie non-consideration of the provisions of the GCA 1949) do not fall within the exceptions to the doctrine of res judicata which are limited to the following situations: fraud or where evidence not available at the original hearing becomes available (see Arnold and others v. National Westminster Bank plc [1991] 3 All ER 41; [1991] 2 AC 93 and Hock Hua Bank Bhd v. Sahari bin Murid)."

[Emphasis Added]

[48] It does not comport with the notion of fairness and justice in that had the trial not been bifurcated, the appellant would have had the opportunity to raise the issue of a subsequent event of OSC's winding up, but not in this instance, where the trial was bifurcated.

[49] It must be appreciated that though the Liability Judgment had described and defined the Time-Period for the Assessment of Quantum, yet the determination of the Quantum was not definite until the determination of the Time-Period Quantum Order. All that the Liability Judgment did was to give a formula for the Time-Period for Assessment of the Quantum with reference to cl 8.1.1 of the MA, which provides for the Commencement of Time-Period being the Commencement Date of the MA and ending on the last day of the AWO issued during the License Period and any extension thereof by the Operators which are the Telcos in Group A and Group B as referred to in the License Agreement.

[50] Moreover, the Liability Judgment requires that the determination of the applicable Time-Period be carried out in an account and inquiry process. In particular Minute (a) of the Liability Judgment provides that PINS liability to pay is "for the period from 21 May 2007 (the Management Agreement date) until the expiry of the period as stated in cl 8.1.1 of the Management Agreement for the Operators (Group A Operators) and the Other Telecommunication Providers (Group B Operators)(which will be determined vide the Account and Inquiry in accordance to (B) below)". [Emphasis Added]

[51] Minute (b) of the Liability Judgment further went on to order that an account and inquiry "be conducted on the Maintenance Fee Payable." We agree with learned counsel for the appellant that a reading of Minutes (a) and (b) together discloses that there are two (2) unknowns which fall to be determined in the account and inquiry proceedings, ie, (1) the expiry of the period in accordance with the MA and (2) the actual Maintenance Fee payable. It would not be wrong to say that the applicable Time-Period to be applied is a Quantum issue to be ventilated and decided in the subsequent Quantum proceedings without derogating or deviating from the terms of the Liability Judgment.

[52] As there was no evidence at all that was led in the Liability Trial vis-à-vis the applicable Time-Period or the actual Quantum save for its description and definition as stated in the formula given, it was the Time-Period Quantum proceedings that descended to the details to determine the Quantum payable.

[53] Indeed, by the same token, the Liability Appeal heard by the Court of Appeal did not decide on the "Extended License Period" as that was not argued before the Court of Appeal hearing the Liability Appeal. The "Extended License Period" was extended only in the SLA, which was entered into some 3 years after the Liability Judgment, and whilst it could be argued in the Liability Appeal by way of adducing fresh evidence, it was not so argued nor did the respondent take any steps to amend or vary the Liability Judgment. The Liability Judge could not have foreseen that the License Period in the MAs would be extended by the Telcos in a SLA dated 1 January 2016 for a period of 10 years after the expiry of the MAs.

[54] After all, the MA only referred to an extension of 5 years or such other period as the parties may agree. However, it is provided in cl 6.1.1 (ix) of the MA that the terms in the License Agreement, to which UDSB is not a party, shall not be terminated by PINS without the prior written consent of UDSB. Additionally, PINS shall not, without the prior written consent of OSC under cl 6.1.1 (x) of the MA, agree to any variation, modification or amendment to the License Agreement and/or the AWO.

[55] Whilst ordinarily upon a breach of an agreement the innocent party would only be able to claim compensation until the expired term of the agreement, here there was a built-in automatic extension clause in the License Agreement at the option of the Telcos. The combined effect of the above cls 6.1.1 (ix) and (x) is such that once the Telcos agreed to the Extended License Period of another 10 years after the expiration of the last AWO under the License Agreement, PINS cannot, to the detriment of OSC, decide not to continue with the MAs with OSC.

[56] By the time of the Assessment of Quantum Order, the Extension was already in place and certain and there does not seem to be any good reason why the Court of Appeal could not rely on what is certain on the Quantum Appeal to allow the Assessment of the Quantum to continue until the last AWO in the Extended License Period.

[57] Thus, we would allow the appellant to raise the issue of the winding up at the Time-Period Quantum stage, having satisfied ourselves that if it is relevant, it would affect the Quantum that is finally determined, for then the Quantum would be assessed up to that date and not beyond. We shall now turn to discuss whether or not the winding up is a relevant event.

Whether The Winding Up Of OSC Was An Avoidable Event Which Would Ordinarily Not Have Happened If PINS Had Not Breached The Contract And Thus Not Relevant For Assessment Of Quantum

[58] The compensatory principle states that compensation is determined on the basis of putting the injured party back to the position as if the contract had not been broken but rather performed. Applying this principle, the winding up of the innocent party would ordinarily not have happened had PINS not breached the contract but instead complied with its terms by making the payments due to OSC.

[59] Unlike the outbreak of a pandemic in iVenture Card Ltd And Others v. Big Bus Singapore Sightseeing Pte Ltd And Others [2022] 1 SLR 302, the outbreak of war in Golden Strait Corporation v. Nippon Yusen Kubishiki Kaisha [2007] 2 AC 353 House of Lords, the introduction of legislation to prohibit the export of wheat in Bunge SA v. Nidera BV [2015] 3 All ER 1082, UK Supreme Court, which are unavoidable and unforeseeable events as in a force majeure, here the winding up of a paltry sum of RM60,000.00 by the Inland Revenue was a preventable and avoidable event not in the nature of a force majeure.

[60] In a case of an anticipatory breach, subsequent events which shed more light on damage suffered at trial, as in The "STX Mumbai" And Another Matter [2015] 5 SLR 1, may be taken into consideration in assessing damages.

[61] PINS had submitted that taxes are assessed on income earned and so its failure to pay tax to the Inland Revenue has nothing to do with the fact that PINS had withheld payment due to OSC for the Operators in Category B that had triggered this derivative action.

[62] Whilst that principle of tax may be true, one must not ignore the realities of business and the cash flow bottlenecks when services have been rendered, but payments are not received. Had payment been made regularly as provided for in the MAs, we doubt OSC would have the problem of not being able to pay the sum of RM60,000.00 for which it was wound up by the Inland Revenue.

[63] We can agree with the appellant that the party winding them up was not PINS but the Inland Revenue and in that sense, the party responsible to wind up OSC was not PINS but the Inland Revenue. However, that does not mean that PINS' non-payment to OSC was not a contributing factor to OSC's winding up. It is fair to say that by its non-payment of Management Fees due and owing to OSC, PINS contributed to the winding up of OSC on ground of the latter's inability to pay its debts when they fell due to the Inland Revenue. It is not a matter of subjective speculation because the law allows one to state what the likely outcome if the contract had been performed.

[64] From that perspective, PINS should not be allowed to rely on OSC's winding up, which in all probabilities would not have happened if PINS had paid OSC regularly and punctually, to now say that the assessment of the Quantum to be paid should be only until the winding up of OSC. It is an extended application of the principle that a party cannot take advantage of its default.

[65] The nature of winding up of a company is that, any time payment is made to the creditors to their satisfaction, a permanent stay of the winding up may be obtained. Any contributory of the company may make payment to the petitioning creditor and get a stay of the winding up order or apply to terminate the winding up under s 492 or 493 of the Companies Act 2016 respectively. Winding up does not spell the end of a company as a liquidator appointed would be able to collect the judgment sum due to the company and pay off all debts of the company in liquidation.

[66] What is more important here is that PINS had taken over the contract of managing the Towers and providing a one-stop centre from OSC, and as such OSC was no longer required to provide such services but instead would be compensated with the quantum as ordered to be determined by the Liability Judge through an Account and Inquiry exercise.

[67] There was no need for OSC to have a staff force to provide such services to PINS anymore from the date PINS took over such services from OSC. The winding up of OSC therefore does not have any effect on the performance of the MAs because it was not required to do so. All that OSC exists for after the Liability Judgment is to receive the Quantum that is due to it after the Quantum Court has assessed the amount. Had there not been any winding up order, OSC as the injured party here, would still not have needed to lift any finger to earn the profits that it claimed against PINS.

[68] The Liquidator appointed would be there to ensure that the quantum received is paid to creditors before paying any excess to the contributories which in this case are the 2 equal shareholders in UDSB and PINS.

[69] The fact that ordinarily all contracts would be terminated upon winding up of the company OSC is not relevant simply because the contracts had been terminated by the repudiatory conduct of PINS even though PINS had not pleaded that fact but the evidence adduced including PINS taking over all accounting records from OSC and preventing OSC from continuing to discharge its obligations under the contracts point inevitably to the fact of wrongful repudiation of the contracts in the MAs.

[70] We are thus in agreement with the Court of Appeal that the subsequent winding up of the respondent OSC is not a relevant event for the purpose of limiting the assessment of the Quantum to be paid until the date of winding up.

Whether The Liability Judgment Is Ambiguous Such That The Court Would Interpret It In A Manner Consistent With The Contractual Principle And Compensatory Principle ("The Interpretation Of Liability Judgment Issue")

[71] It is a cardinal principle of compensation that the end result is to put the injured party in the position it would be if the contract had not been breached. It is not to put the injured party in a far better position now that the contract has been breached. That would be a case of unjust enrichment or over-compensating the injured party.

[72] The injured party, having been prevented from performing the contract, would get compensation for the loss of profit arising from the breach by the defaulting party. The injured party would no longer have to expend costs and expenses in performing the contract because it had been prevented from doing so. It is however a loss of profit and not a loss of revenue that the injured party would be compensated, as had it performed the contract, it would only be able to reap a profit after deducting its costs and expenses.

[73] The other principle to bear in mind is that the Court generally would not rewrite the contract that the parties had entered into. In the rare occasion where they did, they would explain why they did so. Courts would also not give a party more than what it had prayed for and claimed as its relief because to do so would be a denial of natural justice as the defendant ordinarily would only have defended the plaintiff's claim based on what it had pleaded.

[74] Thus, it has been said that where an order of court is capable of being construed to have effect in accordance with or contrary to established principles of law or practice, the proper approach, in the absence of manifest intention, is not to attribute to the judge an intention or a desire to act contrary to such principles or practice but rather in conformity with them. See the case of Sujatha v. Prabhakaran [1988] 1 SLR (R) 631.

[75] The High Court in its Liability Judgment had singled out only one deduction being payment by PINS to MCMC for the license fees and that is because it had allowed PINS' counterclaim against OSC for that item, which OSC had undertaken to pay under the MA. It was also a judgment given based on the pleadings of both parties where neither party pleaded termination of the MAs, much less its unlawful termination and UDSB had proceeded on the basis of the contract in the MAs being performed by the JV Company OSC.

[76] Against that backdrop, PINS would be paying OSC the 20% of the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments due to it and OSC would have to bear all costs and expenses incurred in discharging its three duties and obligations of constructing, maintaining and providing the One Stop Centre services as well as making the Priority Payments and the Repayments for the Bond Issue. OSC would also continue its annual payment to MCMC for the license fees.

[77] The Liability Court had in mind a complete running account which is why the exercise of the Account and Inquiry was for the period from the commencement of the MA until the expiry of the period as stated in cl 8.1.1 of the MA for the Telcos.

[78] The process of the Account and Inquiry would be able to determine in paragraph (d) of the Liability Judgment "...all sums determined to be due to the 1st Defendant within 30 days after the Accounts and Inquiry as stated in (B) above is conducted entirely". Indeed, this was what the plaintiff UDSB prayed for in para 11 of its Statement of Claim. [Emphasis Added]

[79] The subtle change in the language could easily have gone unnoticed. Previously at para (b) of the Liability Judgment, the words used were different with a focus on determining the Maintenance Fee as follows: "(b) that an Account and Inquiry be conducted on the Maintenance Fee Payable by the 2nd Defendant to the 1st Defendant in accordance with the Judgment herein..." [Emphasis Added]

[80] A change from a reference to the "Maintenance Fee" to "all sums determined to be due" would suggest that being a running account, the exercise was more than just to determine the "Maintenance Fee" but to do a complete accounting on all payments under the MAs such that at the end of the day one would have a true picture of the amount due to OSC.

[81] The Liability Court was conscious of the payment scheme as a whole under the MA where the Court noted at para 37 of the Liability GOJ as follows:

"I have carefully perused the Management Agreement and it is observed that cl 6.1.1 (vii) expressly provides that the 2nd Defendant [PINS] covenant with the 1st Defendant [OSC] inter alia to ensure that the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments are paid directly to PINS Capital."

[82] This is to be expected and is provided for in cl 1.4.1 wherein PINS Capital, a wholly-owned subsidiary of PINS, is the vehicle set up to raise the financing by way of bonds issued to finance the construction of the Infrastructures which is expected to gross in millions annually and as the figure in the Expert Report of Jonathan Khong, the Managing Partner of Virdos Lima Consultancy (M) Sdn Bhd said, to the tune of RM222,713,706.25 from the "Realized Revenue" (due on or prior to 8 December 2023) at p 39 of its Report of 8 March 2024.

[83] There was also a Proceeds Assignment dated 14 February 2007 between PINS and PINS Capital, where all the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments are to be paid to PINS Capital first. Under cl 4.1 of the MA, which the Liability Judge specifically referred to in paragraph (a) of the Judgment with respect to the Maintenance Fee payable to OSC, it is provided as follows:

"4.1 For the consideration aforesaid, PINS shall irrevocably and absolutely assigns to PINS Capital all its rights, interest and benefit in the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments. PINS shall simultaneous with the execution of this Agreement execute and deliver to PINS Capital a Proceeds Assignment for the aforesaid assignment. PINS shall immediately notify the Operators of the assignment and instruct the Operators to remit all Rental Proceeds and Other Payments into PINS Capital's designated account by way of a Notice cum Instruction containing, inter alia, the details of the bank account of PINS Capital into which the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments are to be deposited ("Notice cum Instruction"). PINS Capital hereby undertakes to only retain the Repayment Sum towards repayment of the Bonds Issue and return to the Company the balance of the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments ("Balance Sum"). The Company hereby undertakes with PINS, and UDSB that the Company shall make the following, priority payments (before operation costs):

(i) rental to landowners for land rented by PINS pursuant to the Tenancy Agreements;

(ii) yearly obligations to MCMC;

(iii) any other payments to relevant authorities inclusive of any penalties imposed by the relevant authorities or parties."

[Emphasis Added]

[84] This is again reiterated in cl 1.2.2 of the SMA wherein PINS Capital shall retain the Repayment Sum towards repayment of the Bonds Issue and return to the OSC the balance of the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments and OSC shall undertake to make the Priority Payments was also set out.

[85] Another clause specifically referred to by the Liability Judge is cl 3.1 of the SMA which reads:

"3. BALANCE SUM

3.1 PINS and the Company hereby mutually agree that after payment of the Priority Payments, the Company shall be entitled to deduct an amount equivalent to 20% of the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments as the maintenance fee for the maintenance of the Infrastructures by the Company ("the Maintenance Fee")...

Any balance of the Balance Sum after payment of the Priority Payment and deduction of the Maintenance Fee...shall be paid by the Company to PINS ("Remaining Sum'"). Notwithstanding the foregoing obligation to pay the Remaining Sum to PINS, PINS hereby irrevocably instructs the Company to retain the Remaining Sum in a trust account for purpose of utilization to satisfy future Maintenance Fee...".

[Emphasis Added]

[86] The Liability Court could not have rewritten the MA and the SMA for the parties and by "Rental Proceeds" the Liability Court must have included the "balance of the Rental Proceeds and Other Payments" in cl 1.2.2 of the SMA and the undertaking of OSC to make the Priority Payments.

[87] It would be fair to say that the use of the words "Rental Proceeds" is a shorthand used by the Liability Court and it must be read in the context of both cls 4.1 of the MA and 3.1 of the SMA for these two clauses were specifically referred to by the Liability Judge in making paragraph (a) of the Liability Judgment and they made reference to the deduction of Priority Payments which included the payment to landlords for rental of the lands on which the Towers stand which amounted to a substantial payment of RM13,330,673.07 in the calculation in the Expert Report of Jonathan Khong Heng Jun.

[88] Moreover, the reality on the ground by the time the Assessment of Quantum was done was such that the operations of OSC had been taken over by PINS and all accounting books and records had also been taken over by PINS and OSC had stopped performing the MAs, as there were no payments forthcoming from PINS since the matter was filed in the High Court. The Court in assessing Quantum must take this reality into consideration in as much as it has taken the fact of the Extension of the License Period by another 10 years into account in assessing Quantum.

[89] The Liability Judgment must thus be read in the context of the pleadings where neither party pleaded termination. One must then interpret the Liability Judgment, taking into consideration the new circumstances that had arisen after the Liability Judgment. The Court cannot shut its eyes to the fact that OSC was no longer required to perform the contract under the MAs anymore in as much as the Extended License Period had kicked in for an extension of the period of the last AWO under the MAs. Whilst it was performing the contract in the MAs, it would be paid the Maintenance Fee, but then it would also have to incur costs and expenses in earning that Management Fee.

[90] UDSB, as the plaintiff in the High Court below, had pleaded and claimed for the loss of profit arising from PINS' breach of the MAs in paras 27(a), (b) and (c) of the Statement of Claim. To arrive at a loss of profit from the gross revenue, the costs and expenses incurred to generate the revenue must be deducted from the gross revenue. The Court would not generally grant the plaintiff a more favourable sum in loss of revenue than what it had prayed for.

[91] If authority is needed for the above proposition of law, one need not go further than to refer to the Federal Court case of SPM Membrane Switch Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Negeri Selangor [2016] 1 MLRA 1, where it was held that to calculate the loss of profits, the proper sum should be the revenue "[130]...net of all expenses that would be reasonably incurred". It goes without saying that the claiming party (the party not in default or breach) cannot recover from the defaulting party in breach of the contract more than what they rightfully would have profited.

[92] The Liability Judgment does not say that only the payment to MCMC was to be deducted in arriving at the Maintenance Fee and the Liability Judgment must be read in the context of the payment scheme referred to in the MAs where all costs and expenses including financing costs would have to be deducted to arrive at the Maintenance Fee payable in a case where OSC was no longer required to perform the contract.

[93] In the event the Liability Judge was minded not to follow the terms of the MAs had the contract been performed, one would expect some reasons to be given for otherwise the Court would be rewriting the terms of the contracts for the parties. As the Liability Judge had not given any reasons for not following the terms of the MA and SMA where deductions have to be made for the Repayment Sums and the Priority Payments, one would expect to make the Liability Judgment consistent with the MA and SMA. The Liability Judgment cannot be read in a manner giving the innocent party in OSC a more favourable position than what it would enjoy had the contract been performed.

[94] In fact, the initial Expert Report procured by PINS for the Assessment of Quantum proceedings based on the Time-Period Quantum Order had included the following items as costs and expenses to be deducted, which the Assessment of Quantum Judge had excluded, as follows:

[95] The Court of Appeal agreed with the Assessment of Quantum Judge that the "strict terms of the Liability Judgment" must be adhered to and in particular paragraph (a) and (e) which are "clear and unambiguous" and that the Assessment of Quantum Judge had applied "the correct principles of law" in arriving at the amount payable by PINS to OSC.

[96] This resulted in OSC being entitled to the Maintenance Fees after deducting only one item which was part of what the Liability Judge had allowed ie the MCMC Payments contrary to what OSC was obligated to bear which included the Repayment Sum and the Priority Payments besides bearing its own costs and expenses in providing the three services of constructing the towers, maintaining it and providing the One-Stop Centre.

[97] In construing the Liability Judgment, the Court of Appeal must have regard to the context in which the judgment was given, which would include the background of the case, the pleadings, issues to be tried and the grounds of the Judgment. Context is critical and crucial in the interpretation of all documents and more so in a crucial judgment of a court. It provides the colours for the tapestry and the contours for the terrain, without which there would be little appreciation of what is plainly placid.

[98] Such an approach was taken by the Court of Appeal in Rinota Construction Sdn Bhd v. Mascon Rinota Sdn Bhd & Ors [2021] 3 MLRA 647, which held that a purposive approach should be adopted as follows at [18]-[19]:

"After going through the factual matrix and chronological background of this case which lead to this application by the appellant, we are constrained to agree with the learned counsel for the appellant that the learned High Court Judge had erred when His Lordship took a literal and rigid approach in interpreting the order dated 29 August 2012. It is axiomatic that court orders are the derivative and distillation of the important factors like the background of cases, how those cases are pleaded, what redress is being sought by the complainant and what are the court's reasoning process culminating in the granting of the order.

The legal principles on the purposive approach that could be gleaned from the cases referred to us by the appellant's counsel are that the court may:

(a) look at the background to the case Hong Kong Bank (malaysia) Bhd v. Raja Letchumi Ramarajoo & Ors [1996] 1 MLRA 479;

(b) look to the pleadings of the case Newacres Sdn Bhd v. Sri Alam Sdn Bhd [2000] 1 MLRA 184;

(c) look to the ground of judgment Newacres Sdn Bhd v. Sri Alam Sdn Bhd [2000] 1 MLRA 184; and

(d) look at the essential issue of what the court order is supposed to resolve (Privy Council's case Sans Souci Ltd v. VRL Services Ltd [2012] All ER (D) 186 (May); [2012] UKPC 6)..."

[Emphasis Added]

[99] The Court of Appeal in Newacres Sdn Bhd v. Sri Alam Sdn Bhd [2000] 1 MLRA 184 had held that the Court is entitled to look at the pleadings and grounds of judgment in construing an order where there is some seeming ambiguity. The Privy Council in Sans Souci Ltd v. VRL Services Ltd [2012] UKPC 6, an appeal from the decision of the Court of Appeal of Jamaica, propounded a "single coherent process" in interpreting a court order even without an "ambiguity" being there to begin with, as follows:

"[13]...the construction of a judicial order, like that of any other legal instrument, is a single coherent process. It depends on what the language of the order would convey, in the circumstances in which the Court made it, so far as these circumstances were before the Court and patent to the parties. The reasons for making the order which are given by the Court in its judgment are an overt and authoritative statement of the circumstances which it regarded as relevant. They are therefore always admissible to construe the order. In particular, the interpretation of an order may be critically affected by knowing what the Court considered to be the issue which its order was supposed to resolve.

It is generally unhelpful to look for an "ambiguity", if by that is meant an expression capable of more than one meaning simply as a matter of language. True linguistic ambiguities are comparatively rare. The real issue is whether the meaning of the language is open to question. There are many reasons why it may be open to question, which are not limited to cases of ambiguity."

[Emphasis Added]

[100] Likewise, the Australian Federal Court in Lim v. Comcare [2019] 165 ALD 217 at para [40]-[41] also advocated the contextual primacy in interpreting even an unambiguous court order as follows:

"...To pose the question as simply, can ambiguity in court orders be resolved by reference to their external context, obscures the point of what an order sets out to do. The purpose of a court order is, ordinarily, to give effect to a judgment. The judgment is not some kind of penumbral context surrounding the order. Rather the judgment is the source of the order. A court order derives from its originating judgment, as a transfer of land derives from the underlying contract. The order must therefore conform to the judgment, with only such latitude as the judgment allows. Likewise, the transfer must conform to the contract. To speak therefore of the originating judgment as providing context for resolving ambiguity understates the primacy of that judgment as a source of the interpretation of the order.

...

It is impermissible, in my view, as well as being quite unrealistic, to attempt to read, that is, to understand an order in isolation from the context of the reasons for it being made. The Full Court of the Supreme Court of Queensland, in Australian Energy Ltd v. Lennard Oil NL (No 2) [1988] 2 Qd R 230 held that, in interpreting an order framed in unambiguous language, regard should still be had to the reasons given by the Court for making the order because they form part of a context in which the order was made...".

[Emphasis Added]

[101] It cannot be gainsaid that the Liability Judgment could have been made clearer with the benefit of hindsight and where an interpretation of the judgment would not yield a commercial or business sense, the Court is constrained to interpret it in a manner consistent with the terms of the contracts of the parties, the background of the case as pleaded and the pleadings themselves as well as the reliefs sought and its consistency with the principles of compensation. It would be a windfall to compensate OSC based on the revenue generated without the need to lift a finger to undertake any task after the breach by PINS.

[102] With respect to learned counsel for the respondent UDSB, here we are not dealing with a case of a default judgment which was not set aside and then the defendant, when it came to assessment of damages, tried to "roam freely" to indirectly challenge the correctness of the default judgment. The dicta of the UK High Court in New Century Media Limited v. Mr Vladimir Mahkhlay [2013] EWHC 3556 (QB) must be read in its context which is that as the default judgment was not set aside the issue of liability cannot be challenged vis a back-door way in the assessment stage, as follows:

"[32]...Peter Gibson LJ also agreeing, said this:

In my judgment, the true principle is that on an assessment of damages any point which goes to quantification of the damage can be raised by the Defendant, provided that it is not inconsistent with any issue settled by the judgment.

...

[36] Mr Makhlay had a full opportunity to defend the claim on liability. If he disagreed with an aspect of liability that was relevant to quantum, it was for him to challenge the claim at the liability stage. He chose not to do so. He has not sought to set the judgment aside. He cannot now "roam freely" across issues of liability as he wishes to do.

...

[40] Mr Makhlay's approach is tantamount to an abuse of process by way of a back-door attempt to challenge the findings in the judgment. It offends not only a natural sense of justice, but also against the general rule that a party should not be allowed to litigate issues which have already been decided by a court of competent jurisdiction.

[41] The consequences of Mr Makhlay's position being correct would be startling: a Defendant would benefit from failing to lodge a defence on liability and by simply submitting to a judgment in default, holding his powder dry until the quantum stage. He would then be able to mount, essentially unfettered, all and any arguments on liability at the quantum stage that he wished — probably, as has happened here, without any proper pleading or identification of the issues.

[42] In this regard I have been taken to a footnote to s 8 of Zuckerman on Civil Procedure (2007). It is stated that judgment under CPR 12 "is more common than judgment on the merits... There were 310 judgments after trial given in the Queen's Bench Division in 2004, whilst 657 sets of proceedings were determined by judgment in default...". More recent statistics suggest that there were 1,292 judgments in default in the Queen's Bench Division in 2011, as against some 193 trials concluded in the months January to December 2011. It does not appear to me conducive to the administration of justice, or to the delivery of the overriding objective, for a Claimant seeking to defend his position on quantum by reference to arguments on liability not to be required to raise those arguments at the appropriate stage, namely at the liability stage pre-judgment."

[Emphasis Added]

[103] We have no quibble with the above sound principle, which was followed by our Court in Marl Jaya (M) Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Malaysia & Ors (Encl 50) [2017] MLRHU 848.

[104] PINS is challenging the Quantum assessed in arguing that while the Liability Judgment remains intact, the interpretation of it must be made in the context in which it was delivered, having regard to the factual matrix of the case, the way the parties had pleaded their respective claims and counterclaims, the grounds of the judgment and the changed circumstances and the terms of the agreements entered into by the parties.

[105] The clarity in the MAs having being renewed for another 10 years happened some 3 years after the Liability Judgment was entered and some 4 years before the Time-Period Quantum Judge decided on the cut-off date for the period of Assessment. In as much as UDSB did not object to the approach of taking a subsequent event in the Extended License Period to be taken into account, it would be a breach of natural justice if the fact of PINS having to bear all costs and expenses in generating the Rental Proceeds are not taken into account before determining the amount to be paid to OSC. OSC would be placed in a super favourable position where it does not have to incur any costs and expenses other than payments to MCMC in receiving the full enjoyment and benefit of the Maintenance Fee.

[106] The way the Liability Judgment is worded, especially in paragraph (d) thereof, is such that it is versatile enough for the Account and Inquiry to take into consideration all costs and expenses incurred as if there had not been any breach. While that hypothetical scenario is used to work out the Account and Inquiry, it is tempered with the harsh reality that PINS is now bearing all the risks and incurring all the costs and expenses in running the JV Company as if there had been no breach of the MAs.

[107] In resolving the Interpretation of the Liability Judgment Issue, the Federal Court in SPM Membrane Switch Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Negeri Selangor [2016] 1 MLRA 1 prescribed the approach below in interpreting documents as follows:

"[68]... when one has to choose between two competing interpretations, the one which makes more commercial sense should be preferred if the natural meaning of the words is unclear. It is noteworthy that the same approach was taken by Lord Hodge (in the majority decision of Arnold v. Britton And Others), where His Lordship accepted the unitary process of construction in Rainy Sky SA v. Kookmin Bank [2011] 1 WLR 2900 para 21 that:

... if there are two possible constructions, the Court is entitled to prefer the construction which is consistent with business common sense and to reject the other.

[69] Thus it would appear that even Arnold v. Britton And Others [2015] UKSC 36 is not totally opposed to the application of business common sense approach in construing a contract, in the absence of clear words."

[Emphasis Added]

[108] We are not dealing with a case of a wrong Judgment where the only recourse is to appeal. Here we are dealing with a Liability Judgment where events that happened subsequent to the Liability Judgment, like the Extended License Period and the reality of PINS having taken over the performance of the MAs such that the Court cannot shut its eyes to the situation prevailing at the time the Assessment of Quantum was heard some 10 years after the Liability Judgment.

[109] Things have a way of gaining greater clarity with the passage of time when the dust of the conflict has settled after some 10 years. It had become clear after the Liability Judgment 2013 that the Telcos would be extending the License Agreement with PINS in 2016. The terms of the License Agreement cannot be altered by PINS without the consent of OSC such that any Extension of the License Agreement would accrue to the benefit of OSC, the agreed special vehicle incorporated to provide the Services under the MAs.

[110] Lest it be said that we have deviated from the terms of the Liability Judgment, we would buttress our confidence in the dicta of the Federal Court in Takako Sakao (f) v. Ng Pek Yuen (f) & Anor (No 2) [2009] 3 MLRA 92, at p 94, as follows:

"We have ample jurisdiction to fashion specific relief, in this instance the remedy of injunction, to meet the justice of this case based on its peculiar facts."

[111] Just as the Court has ample jurisdiction to make consequential orders to give effect to its judgment as was held in Tan Soo Bing & Ors v. Tan Kooi Fook [1996] 2 MLRA 164, the Court in a case where there has been subsequent events after the Liability Judgment pointing irresistibly to the fact that the party in breach had taken over the performance of the contract in the Concession Works, the Court must interpret the Liability Judgment in the light of the new facts prevailing at the point of the Assessment of the Quantum exercise. Very significantly, though neither party pleaded termination, the action of PINS in taking over the accounting records and in preventing OSC from continuing to perform the contracts in carrying out the Concession Works would constrain the Court to apply the Liability Judgment with necessary modifications in the light of the current changed circumstances which facts the parties are not disputing.

[112] It is not then a case of the Assessment of Quantum Judge deviating from and disregarding the terms of the Liability Judgment but rather one in which the dynamics of the joint venture have changed so drastically to the point of having disappeared. With no need to deploy staff and direct any efforts to carry out the Concession Works, OSC would nevertheless be entitled to what it would have been entitled had the contract been performed in a hypothetical situation where there are no risks involved.

[113] We must not for a moment forget that the determination of what is the Quantum payable for a breach of a contract is a single continuous exercise, though sometimes bifurcated for convenience and with the consent of the parties. As such nothing is final until the quantum is determined and parties and the Court would sometimes clarify that there shall only be one appeal after assessment of the quantum so that all issues, related as they would be with respect to liability and quantum, be ventilated in a single appeal rather than two streams of appeal like in this case where there was an appeal on Liability up to leave stage at the Federal Court followed by the second stream of appeal on Quantum right up to the Federal Court on substantive merits of the Quantum Appeals.

[114] As it is, now is 2026, some 13 years after the Liability Judgment. Much water has flowed under the bridge. The joint-venture has, for all intents and purposes, disintegrated and disappeared. A proper accounting has still to be done pursuant to the Account and Inquiry ordered by the Liability Judge so as to determine what is the Quantum to be paid to the JV Company that had not been required to do any of the Concession Works subsequent to 3 May 2011. See para [36] of the Liability Judgment which was upheld by the Liability Court of Appeal as follows:

"36. The Plaintiff further submitted that the 2nd Defendant and the 3rd Defendant had deprived the 1st Defendant of funds to sustain operations subsequent to 3 May 2011, resulting in the 1st Defendant being unable to maintain the 87 towers. In relation to this point, the Plaintiff alleged that the 2nd Defendant without notice or without issuing letter of termination of the Management Agreement proceeded to take over the functions of the 1st Defendant to perform the Construction Services, Maintenance Services & OSC Services under the Management Agreement.

...

41. In these circumstances it appears that the 2nd Defendant and the 3rd Defendant has deprived the 1st Defendant of funds to sustain operations after 3 May 2011, resulting in the 1st Defendant being unable to maintain the 87 towers.

42. In fact, DW1 admitted in cross-examination that in May 2011, the 2nd Defendant took over the functions of the 1st Defendant to perform the Construction Services, Maintenance Services & OSC Services under the Management Agreement."

[Emphasis Added]

[115] The nature of an account and inquiry is to capture all costs and expenses incurred so that at the end of the day, one could ascertain the financial position and amount due to OSC had the joint-venture contract not been breached. That is the consequence that PINS has to suffer for breaching the terms of the JV in not fulfilling its obligations to make payments of Maintenance Fees to OSC, the JV Company.

[116] In the case of an ongoing JV, the Account and Inquiry exercise would take into consideration the actual costs and expenses incurred in consideration of the payment of the Management Fees to the JV Company. The Liability Judge made her judgment based on the pleadings of the parties, where neither referred to any termination of the MAs. By the time of the Assessment of Quantum exercise the JV Company was already in liquidation but was nevertheless not required to perform any of the Concession Works. There is no cogent reason why all costs and expenses incurred should not be taken into account in a case where the JV Company OSC remains to collect Maintenance Fees without the need to do any work.

[117] The Liability Judgment as worded was clearly delivered in the context where the plaintiff had not pleaded for damages to be assessed as its primary relief which generally is prayed for arising from unlawful termination of an agreement. It did pray in para 12 "Further and/or in the alternative, damages to be assessed by the Honourable Court." The Liability Court did not grant the prayer as nowhere in the pleadings did either party refer to the termination of the MAs.

[118] In assessing Quantum in the light of changed circumstances which parties are not disputing, the Court is not throwing out the Liability Judgment but rather tailoring it to meet the ends of justice where it is impossible to revert to the status quo ante before the breach. It is not a case of going against or avoiding the terms of the Liability Judgment but rather applying it with an appreciation of the changed circumstances on the ground.

[119] As alluded to earlier, UDSB and with that OSC has no issue of the Court of Appeal in the Quantum Appeal taking into consideration that there was a subsequent event of Extension of the License Period in the SLA such that the Quantum is to be calculated taking into consideration the extension of 10 years after the expiry of the initial LA. Clearly the Liability Judge could not have foreseen that and did not expressly provide for that in her Liability Judgment which was couched in descriptive terms as "for the period from 21 May 2007 (the Management Agreement date) until the expiry of the period as stated in cl 8.1.1 of the Management Agreement for the Operators (Group A Operators) and the Other Telecommunication Providers (Group B Operators) (which will be determined vide the Account and Inquiry in accordance to (B) below)". [Emphasis Added]