Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Azizah Nawawi, Collin Lawrence Sequerah, Alwi Abdul Wahab JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: W-04(IM)(NCVC)-20-01-2022]

28 November 2025

Hire Purchase: Repossession — Appeal against finding of High Court that application for leave to issue statutory notices under s 16(1A) of the Hire Purchase Act 1967 must be made inter parte — Whether mandatory for originating summons filed for purpose of obtaining leave under s 16(1A) of the HPA to be filed inter parte.

The respondent had entered into a hire purchase agreement dated 4 January 2008 (agreement) with the appellant in respect of a recondition used vehicle bearing registration No WQQ 2628 (vehicle). The respondent defaulted in his repayments and the appellant vide Originating Summons No WA-A74-96-01/2018 applied to the Magistrate's Court for leave to issue statutory notices to commence the exercise of its rights to repossess the vehicle. Given that the 2 conditions under s 16(1A) of the Hire Purchase Act 1967 (HPA 1967) ie that instalment payments exceeding 75% of the vehicle's cash price had been paid, and that respondent had defaulted in 2 consecutive instalment payments (statutory conditions), the leave as prayed for was granted. The respondent ignored the statutory notices that were served on him and failed to pay the outstanding sum. Upon expiry of the 21 days period of the Fourth Schedule Notice, the appellant proceeded with the repossession of the vehicle, commenced proceedings against the respondent and obtained judgment for the outstanding amount. The vehicle was repossessed 11 months after the issuance of the Fourth Schedule Notice. The respondent applied unsuccessfully to set aside the leave granted by the Magistrate's Court on the sole ground that the application for leave was made on an ex parte basis instead of inter partes. The High Court upon appeal by the respondent held that an application for leave to repossess under ss 16(1A) and (1B) of the HPA 1967 could not be made ex-parte and that granting ex parte leave and repossessing the vehicle without serving the necessary documents violated the principles of natural justice and the audi alteram partem rule as the hirer was entitled to be heard at every stage of the repossession procedure. The High Court accordingly allowed the appeal and set aside the leave that was granted by the Magistrate's Court. Hence the instant appeal by the appellant on the legal issue of whether it was mandatory for an originating summons filed for the purpose of obtaining leave of court under s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967 to be filed inter parte.

Held (allowing the appeal)

(1) The appellant's right to repossess a hire purchase vehicle arose directly from statute and did not require any prior order of the court as was clear from the provisions of s 16(1) of the HPA 1967. (para 37)

(2) The purpose of the application to the court under s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967 was limited only to obtaining leave to issue the statutory notices in situations were more than 75% of the vehicle's cash price had been paid by the respondent. The requirement for leave served as a procedural safeguard to ensure that the statutory conditions were satisfied before the statutory notice was issued for the purpose of repossession. Such leave was not an authorization to repossession but merely permitted the appellant to begin the statutory notice process required under the HPA 1967. (paras 38-40)

(3) The filing of an application by way of ex parte Originating Summons was allowed under the Rules of Court 2012 where the application was simply to prove that the instalment payments had exceeded 75% of the vehicle's cash price and there were 2 consecutive defaults by the respondent in the hire purchase account. (para 41)

(4) The right to be heard was already incorporated in the Fourth Schedule Notice. In the circumstances it could not be said as held by the High Court that the application for leave under s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967 must be made inter parte and that any breach of the same amounted to a breach of natural justice. (para 43)

Case(s) referred to:

BBMB Kewangan Bhd v. Tan Swee Heng & Anor [2002] 2 MLRH 458 (refd)

Credit Corporation (M) Bhd v. The Malaysia Industrial Finance Corporation & Anor [1975] 1 MLRH 419 (refd)

Dr Lourdes Dava Raj Curuz Durai Raj v. Dr Milton Lum Siew Wah & Anor [2020] 5 MLRA 333 (refd)

Low Ping Ming v. MBf Finance Bhd [1999] 4 MLRH 106 (refd)

Metro Tyre Service Centre Sdn Bhd v. Wilfred Jolly [2003] 3 MLRH 217 (refd)

Ong Siew Hwa v. UMW Toyota Motor Sdn Bhd [2018] 5 MLRA 1 (refd)

Tuan Haji Ahmed Abdul Rahman v. Arab-Malaysian Finance Berhad [1995] 2 MLRA 155 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Hire-Purchase Act 1967, ss 2, 16, (1), (1A), (1B), (1C), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7)

Hire-Purchase (Application for Permit and Repossession Procedure) Regulations 2011, r 15(1)

Rules of Court 2012, O 41 r 1(8), O 85A

Counsel:

For the appellant: Tan Hong Kait (Divani Keruna Nithi with him); M/s Sidek Teoh Wong & Dennis

For the respondent: Absent

JUDGMENT

Azizah Nawawi JCA:

Introduction

[1] This is an appeal against the decision of the learned High Court Judge dated 10 March 2020 in allowing an appeal by the respondent against the decision of the Magistrate dated 17 October 2019 in dismissing the respondent's Notice of Application to set aside the leave granted under the s 16(1A) of the Hire-Purchase Act 1967 ("HPA 1967").

The Salient Facts

[2] Vide a Hire-Purchase Agreement dated 4 January 2008 ("the Agreement"), the appellant hired out a reconditioned used vehicle, namely a Mercedes Benz CLS 350 bearing registration number WQQ 2628 ("the vehicle"), to the respondent.

[3] The respondent had breached the Agreement by failing, refusing, and/or neglecting to make the instalment payments on time, and there were outstanding instalments for at least seven (7) months as of January 2017.

[4] Therefore, the appellant intended to repossess the vehicle pursuant to the HPA 1967. Since the respondent had already made instalment payments exceeding seventy-five percent (75%) of the vehicle's cash price, the appellant, in accordance with the provisions of the HPA 1967, was required to obtain leave of the Court before issuing the statutory notices to commence the exercise of its rights to repossess the vehicle.

[5] The appellant then filed Originating Summons No.: WA-A74-96-01/2018 and applied for leave from the Magistrates' Court on 25 January 2018. Under s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967, the conditions that must be satisfied before leave may be granted are:

(i) Instalment payments exceeding 75% of the cash price; and

(ii) At least two (2) consecutive instalment defaults committed by the respondent.

[6] Since both conditions under s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967 were fulfilled, the Magistrates' Court granted the leave sought by the appellant.

[7] The appellant complied with the Court's order and the provisions of the HPA 1967 by issuing the statutory notices to the respondent before carrying out the repossession process of the vehicle, as required under the Fourth Schedule.

[8] A notice under r 15(1) of the Hire-Purchase (Application for Permit and Repossession Procedure) Regulations 2011 dated 16 March 2018 was also issued and sent by registered post.

[9] Despite having been served with the Statutory Notices and that the respective periods had expired, the respondent had completely ignored the said Notices and continued to refuse and/or fail to pay the outstanding amount.

[10] After the expiry of the twenty-one (21) day period of the Fourth Schedule Notice, the appellant then proceeded with the physical repossession of the vehicle, and the vehicle was successfully repossessed on 15 February 2019. This was approximately eleven (11) months after the Fourth Schedule Notice was issued.

[11] An acknowledgment of receipt letter dated 18 February 2019 under s 16(4) of the HPA 1967 was also sent to the respondent by registered post.

[12] At that time, the appellant had also initiated legal proceedings against the respondent to claim the total outstanding sum owed by the respondent and had obtained a Judgment dated 30 April 2018 against the respondent.

[13] However, since the Respondent had also ignored this Judgment, the appellant had no other alternative but to commence the repossession process.

[14] On 31 May 2019, the respondent filed a Notice of Application before the Magistrates' Court to set aside the leave granted by the Magistrates' Court.

[15] The only ground relied by the respondent is that the application for leave via the Originating Summons should have been made inter partes, and not ex parte.

[16] After hearing the parties, on 17 October 2019 the Magistrate had dismissed the respondent's Notice of Application (Annexure 5) with costs.

[17] Dissatisfied with this decision, the respondent had filed a notice of appeal in the High Court. The High Court allowed the respondent's appeal on 10 March 2020 and set aside the leave order granted by the Magistrate.

[18] Hence the appellant applied for leave to appeal. Leave was granted for the substantive appeal against the decision of the learned Judge in setting aside the leave order granted by the Magistrate.

Decision of the High Court

[19] The learned High Court Judge has allowed the respondent's appeal based on the following grounds:

"[11] Firstly, it is trite law that an irregular judgment can and ought to be set aside ex debito justitae (as a matter of right) irrespective of merits and without terms when it is clearly demonstrated to the satisfaction of the court that the judgment had not been regularly obtained even when the timeline provided under the rules had been complied with (see the Federal Court decision in Tuan Haji Ahmed Abdul Rahman v. Arab-Malaysian Finance Berhad [1995] 2 MLRA 155). Thus, if the Ex-Parte Order in this case was wrongly obtained by the Respondent, the said Ex-Parte Order must be set aside.

[12] Secondly, I do take note of the Respondent's objections on the defects of the Appellant's Affidavit in Support for the purported non-compliance of the provisions of O 41 r 1(8) of the Rules of Court 2012. Be that as it may, the Appellant had applied orally for leave to use the said defective affidavits pursuant to the provisions of O 41 Rule on the grounds that it does not prejudice the Respondents. Premised on the Federal Court decision of Megat Najmuddin Dato' Seri (Dr) Megat Khas v. Bank Bumiputra Malaysia Bhd [2002] 1 MLRA 10 which discourages the raising of technical objections and that case should be decided on the merits, I allowed the Appellant's application.

[13] Thirdly, I am of the view that the Ex-Parte Order must be served on the Appellant prior to the Vehicle being repossessed. In this case, the Order was only served to the Appellant on 29 March 2019 despite the vehicle being repossessed on 15 February 2019. Had it been served on the Appellant earlier, they could have taken steps to set it aside immediately.

[14] Fourthly, having reviewed the provisions of ss 16(1A) and (1B) of the Hire-Purchase Act 1967, I am inclined to agree with the Appellant's submissions that an application for leave to repossess such as in the present case before me cannot be done ex parte as it would defeat the very purpose for which Parliament amended the provisions of the previous s 16(1A) of the legislation concerned. In addition, I take the view that the position taken by the Respondent that the leave application can be done ex parte is also not supported by O 85A of the Rules of Court 2012.

[15] Lastly, this Court agrees with the Appellant's contention that by granting the leave application ex parte and the Appellant then proceeding to repossess the Vehicle without serving the papers not the Ex-Parte Order on the Appellant, there was a clear breach of the principles of natural justice and the ' audi alteram partem rule'. To my mind, the Appellant had the right to be heard at all material times and at every step of the repossession exercise (see the judgment of Tengku Maimun CJ in Dr Lourdes Dava Raj Curuz Durai Raj v. Dr Milton Lum Siew Wah & Anor [2020] 5 MLRA 333)."

Our Decision

[20] The only legal issue in this appeal is whether it is mandatory for an Originating Summons filed for the purpose of obtaining leave of court under s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967 to be filed inter partes.

[21] Before we deal with the interpretation of s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967, let us appreciate the positions of parties under the Agreement. A hire-purchase agreement is a credit arrangement whereby the hirer is given possession of the goods while legal ownership remains with the owner or financier until all instalments are fully paid. Under such an arrangement, the hirer may use the goods immediately, subject to payments of the agreed deposit and monthly instalments. Ownership of the goods will only transfer to the hirer after the completion of all payments. As ownership remains with the financier during the term of the agreement, the financier may repossess the goods in the event of default, provided that all statutory requirements, such as those under the HPA 1967, have been strictly complied with.

[22] Therefore, under the Agreement, the ownership of the vehicle remains with the appellant whilst the respondent is only the hirer of the vehicle. This is based on s 2 of the HPA 1967 which provides as follows:

"owner" means a person who lets or has let goods to a hirer under a hire-purchase agreement and includes a person to whom the owner's rights or liabilities under the agreement have passed by assignment or by operation of law."

[23] The following cases have explained the relationship and the rights of the parties under a hire-purchase agreement.

[24] In BBMB Kewangan Bhd v. Tan Swee Heng & Anor [2002] 2 MLRH 458, the Court held as follows:

"In any case, even though the hirer was the registered owner of the vehicle, he was in law only a person who had possession and use of the car. This fact does not make him the legal owner of the vehicle."

[25] In Low Ping Ming v. MBf Finance Bhd [1999] 4 MLRH 106, Justice Steve Shim said as follows:

"A common characteristic or feature of such an agreement is that the hirer has the option of purchasing the goods. And throughout the period of hire-purchase, title to the goods remains with the owner. It is common practice nowadays for a finance company to be involved in a hire-purchase transaction as owner. For example the finance company buys the goods from the dealer who is paid the price and the finance company then steps into the dealer's shoes and becomes the owner for the purpose of the hire-purchase agreement. In this way, the finance company becomes the owner as well as financier."

[26] In Metro Tyre Service Centre Sdn Bhd v. Wilfred Jolly [2003] 3 MLRH 217, the Court held as follows:

"The legal owner is the person who owns and has an undisputed legal title to the vehicle. This is what the relevant section of the Hire Purchase Act is giving effect to."

[27] A classic description of a hire-purchase agreement was given by the Federal Court in Ong Siew Hwa v. UMW Toyota Motor Sdn Bhd [2018] 5 MLRA 1, which is as follows:

"... it is provided that if the hirer duly performed and observed all the stipulations and conditions in this agreement and pay to the owner all sums of money payable to the owner by the hirer, the hirer shall have an option of purchasing the goods and upon payment of the last instalment, the hirer is deemed to have exercised such option and the hiring shall come to an end and the goods shall become the property of the hirer and the owner shall assign all rights, benefits and interests in the goods to the hirer. But, until the option has been exercised, the goods shall remain the absolute property of the owner and the hirer shall not have any right or interest in the goods other than of a bailee. It must also be added that the fact that (as shown in the registration card) (p 270, rekod rayuan (Vol 6)) the plaintiff was the registered owner of the car did not make him the legal owner of the car."

[28] In the present case, it is not in dispute that the respondent was the hirer under the hire-purchase agreement whilst the ownership remained with the appellant until the respondent had paid all the sums of money payable to the appellant under the agreement. Therefore, until the respondent had exercised his option to purchase the car by paying the total rentals and fulfilling all his obligations under the agreement, no property in the car passed to the respondent. (see Credit Corporation (M) Bhd v. The Malaysia Industrial Finance Corporation & Anor [1975] 1 MLRH 419)

[29] The next issue is what happens when the hirer fails to make payments under the agreement. This is where s 16 of the HPA 1967 is relevant. Section 16 reads:

"Repossession

16. Notices to be given to hirer when goods repossessed

(1) Subject to this section, an owner shall not exercise any power of taking possession of goods comprised in a hire-purchase agreement arising out of any breach of the agreement relating to the payment of instalments unless the payment of instalments amounts to not more than seventy-five percent of the total cash price of the goods comprised in the hire-purchase agreement and there have been two successive defaults of payment by the hirer and he has served on the hirer a notice, in writing, in the form set out in the Fourth Schedule and the period fixed by the notice has expired, which shall not be less than twenty-one days after the service of the notice.

(1A) Notwithstanding subsection (1), if the payment of instalments made amounts to more than seventy-five percent of the total cash price of the goods comprised in a hire-purchase agreement and there have been two successive defaults of payment by the hirer, an owner shall not exercise any power of taking possession of the goods comprised in the hire-purchase agreement arising out of any breach of the agreement relating to the payment of instalments unless he has obtained an order of the Court to that effect.

(1B) Where an owner has obtained an order of the Court under subsection (1A) and he has served on the hirer a notice, in writing, in the form set out in the Fourth Schedule and the period fixed by the notice has expired, which shall not be less than twenty-one days after the service of the notice, the owner may exercise the power of taking possession of goods referred to in subsection (1A).

(1C) Where a hirer is deceased, an owner shall not exercise any power of taking possession of goods comprised in a hire-purchase agreement arising out of any breach of the agreement relating to the payment of instalments unless there has been four successive defaults of payment.

(2) An owner need not comply with subsection (1) if there are reasonable grounds for believing that the goods comprised in the hire-purchase agreement will be removed or concealed by the hirer contrary to the provisions of the agreement, but the onus of proving the existence of those grounds lies upon the owner.

(3) Within twenty-one days after the owner has taken possession of goods that were comprised in a hire-purchase agreement he shall serve on the hirer and every guarantor of the hirer a notice, in writing, in the form set out in the Fifth Schedule.

(4) Where the owner takes possession of goods that were comprised in a hire-purchase agreement he shall deliver or cause to be delivered to the hirer personally a document acknowledging receipt of the goods or, if the hirer is not present at that time, send to the hirer immediately after taking possession of the goods a document acknowledging receipt of the goods.

(5) The document acknowledging receipt of the goods, required under subsection (4) shall set out a short description of the goods and the date on which, the time at which and the place where the owner took possession of the goods.

(6) If the notice required by subsection (3) is not served, the rights of the owner under the hire-purchase agreement thereupon cease and determine; but if the hirer exercises his rights under this Act to recover the goods so taken possession of, the agreement has the same force and effect in relation to the rights and liabilities of the owner and the hirer as it would have had if the notice had been duly given.

(7) Before and when exercising the power of taking possession the owner or his servant or agent shall, in addition to the provisions of this Act comply with any regulations relating to the manner of taking possession as may be prescribed."

[30] Under s 16(1), it is provided that an owner cannot repossess goods under a hire-purchase agreement for non-payment of instalments unless all of the following conditions are met:

(i) Not more than 75% of the total cash price has been paid;

(ii) The hirer had missed two instalment payments in a row; and

(iii) The owner had given the hirer a written notice (using the Fourth Schedule form), and at least 21 days have passed since the notice was served on the hirer.

[31] Under s 16(1), the owner is not entitled to repossess the goods under a hire-purchase agreement unless the hirer has failed to pay more than 75% of the total cash price, has missed at least two consecutive instalments, and the owner has served a written notice in the prescribed form (Fourth Schedule) with at least 21 days having elapsed after service. Repossession is therefore lawful only when all these three conditions are satisfied, and the failure to meet any of the conditions renders repossession unlawful under the HPA 1967.

[32] In respect of s 16(1A), it provides that if the hirer has already paid more than 75% of the total cash price and then misses two instalments in a row, the owner cannot repossess the goods for those payment defaults unless the owner gets a court order before repossession. Therefore, getting a court order is a prerequisite in s 16(1A) before repossession can commence.

[33] Under s 16(1B), it provides that if the owner gets a court order under s 16(1A) and then serves the hirer a written notice (Fourth Schedule form), and at least 21 days have passed since the notice was served, the owner may then repossess the goods.

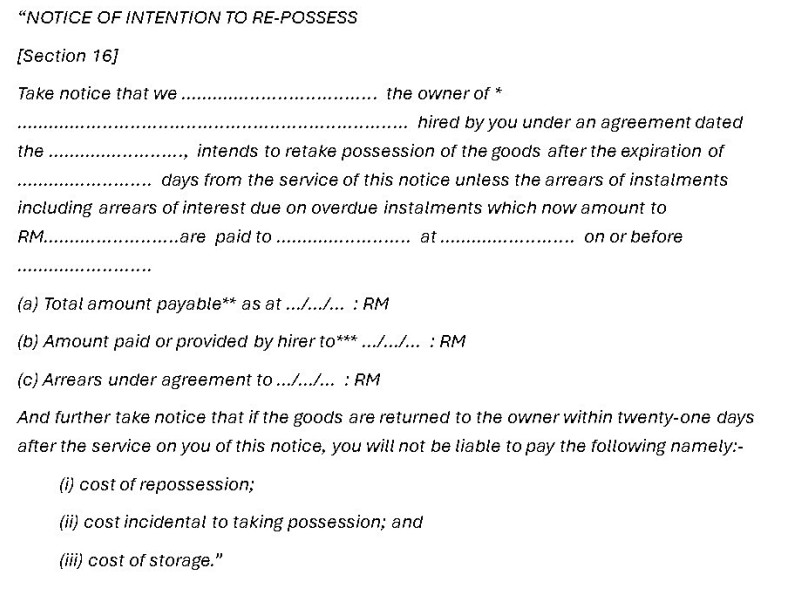

[34] The Fourth Schedule form reads as follows:

[35] Subsection 16(1A) requires the owner to obtain a court order before he can secure possession of the car. The next issue then is whether the requirement to obtain the leave of court via the filing of the Originating Summons pursuant to s 16(1A) must be filed ex parte or inter partes.

[36] It is the decision of the learned High Court Judge that the application via an Originating Summons must be served on the respondent. The learned Judge held that an application for leave to repossess under ss 16(1A) and (1B) of the HPA 1967 cannot be made ex parte. His reasons are that proceeding without notifying the hirer would defeat the purpose of the statutory amendments and is inconsistent with O 85A of the Rules of Court 2012. The learned Judge also held that granting ex parte leave and repossessing the vehicle without serving the necessary documents violated the principles of natural justice and the audi alteram partem rule, as the hirer was entitled to be heard at every stage of the repossession procedure.

[37] We are of the considered opinion that the appellant's right to repossess a hire-purchase vehicle arises directly from statute and does not require any prior order of the Court. This can be seen from s 16(1) which provides that the owner may repossess goods under a hire-purchase agreement only if the hirer has paid not more than 75% of the total cash price, has defaulted on at least two consecutive instalments, and has been served with a Fourth Schedule notice, with 21 days having passed since its service.

[38] Therefore, we find that the purpose of the appellant's application to the Court under s 16(1A) is limited only to obtaining leave to issue the Statutory Notices in situations where more than 75% of the vehicle's cash price has been paid by the Respondent. This requirement for leave serves as a procedural safeguard to ensure that the statutory conditions, namely the existence of two consecutive instalment defaults and the applicability of the 75% rule, have been satisfied before the statutory notice is issued for the purpose of repossession.

[39] We emphasize that this leave is not an authorization to repossess the vehicle. It merely permits the Appellant to begin the statutory notice process required under the HPA 1967. Actual repossession may only be carried out after the Statutory Notices are duly served and the statutory period had expired without any payment made by the respondent.

[40] Therefore, we are of the considered opinion that the application to the Court serves the narrow and specific purpose of enabling the appellant to issue the Statutory Notices in compliance with the HPA 1967, while simultaneously preserving the Respondent's added protection in cases where more than 75% of the cash price has been paid.

[41] As such, we agree with the appellant that the Rules of Court 2012 allows an application for an Originating Summons to be filed ex parte when the application is simply to prove to the Court that the instalment payments have exceeded 75% of the vehicle's price and that there were two (2) consecutive defaults on the hire-purchase account by the Respondent.

[42] Indeed in both s 16(1) and s 16(1A) of the HPA 1967, the right to be heard is already incorporated in the statutory notice, the Fourth Schedule. This statutory notice informs the hirer that the owner intends to repossess the goods after a specified number of days unless all outstanding instalments and interest are paid by a stated deadline. It also sets out the total amount payable, the amount already paid, and the arrears. If the hirer is not happy with the statutory notice after having been served with the same, then the hirer may initiate the process to set aside the statutory notice.

[43] As such, we cannot agree with the learned Judge that the application for leave under s 16(1A) must be made inter partes and any breach of the same amounts to a breach of natural justice. The purpose of getting the Court's leave to issue Statutory Notices is to ensure that the twin requirements under s 16(1A) has been met. The only difference between s 16(1) and s 16(1A) is that under s 16(1A), more than 75% of the cash price has been paid. Since the hirer has paid more than 75% of the loan agreement, it is only fair that before the car can be repossessed, leave must be obtained from the court to ensure the requirements of s 16(1A) has been met.

Conclusion

[43] For the aforesaid reasons, we allow the appeal and we set aside the decision of the learned Judge and we reinstate the decision of the Magistrates' Court. Since this appeal was heard in the absence of the respondent, who has since been adjudged a bankrupt and has failed to attend the Court hearing, we make no order as to costs.