Federal Court, Putrajaya

Abdul Rahman Sebli CJSS, Hasnah Mohammed Hashim CJM, Zabariah Mohd Yusof, Abdul Karim Abdul Jalil, Vazeer Alam Mydin Meera FCJJ

[Civil Appeal No: 01(f)-5-02-2024(W)]

20 January 2025

Revenue Law: Stamp duty — Assessment — Whether fixed or ad valorem stamp duty payable under Stamp Duty Act 1949 ('Act') on a commercial contract, namely, an Asset Purchase Agreement — Whether Agreement fell within ambit of s 21(1) of Act, and Item 32 of First Schedule to Act

This appeal concerned the issue of whether fixed or ad valorem stamp duty was payable under the Stamp Duty Act 1949 ('Act') on a commercial contract, namely, an Asset Purchase Agreement. On 6 February 2020, the appellant company entered into an Asset Purchase Agreement ('the Agreement') with Martin-Brower Malaysia Co Sdn Bhd to purchase certain assets and liabilities. The appellant through its solicitors applied to the respondent for assessment of stamp duty payable on the Agreement. The respondent assessed the Agreement with ad valorem duty of RM399,196.00 on the basis that the Agreement fell within the ambit of s 21(1) of the Act and Item 32 of the First Schedule to the Act ('Assessment'). The appellant made a payment of RM399,196.00 to the respondent under protest with a Notice of Objection as required under s 38A of the Act. On 11 April 2020, the appellant lodged an appeal against the Assessment on grounds that the Agreement should be assessed based on Item 4 of the First Schedule of the Act, wherein only a fixed stamp duty of RM10.00 was payable. The respondent rejected the appellant's appeal and maintained the earlier decision to impose ad valorem duty on the instrument. Aggrieved, the appellant appealed to the High Court by way of a Case Stated pursuant to s 39 of the Act, where the High Court allowed the appellant's appeal. The respondent appealed against the High Court's decision to the Court of Appeal, which allowed the respondent's appeal. The Court of Appeal's rationale for the decision was: (a) the title of the acquired assets under the Agreement was passed to the respondent under the Agreement by virtue of the contractual deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement. Hence, the Agreement constituted a conveyance on sale under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule; and (b) the Agreement did not come within s 21(1) of the Act as the fixed assets that were sold under the Agreement came within the meaning of 'goods', which was an exception under the said provision. Hence, the present appeal by the appellant in which, among others, the following issues, required determination: (i) whether the Agreement was a 'conveyance on sale' within the meaning of s 2 of the Act, thus being chargeable with ad valorem duty; (ii) whether the fixed assets (part of the acquired assets) sold under the Agreement fell within the expression 'goods' as mentioned under s 21(1) of the Act, thus being excluded from the operation of the said section and not attracting ad valorem duty; and (iii) whether the respondent as a Collector of Stamp Duties could raise a stamp duty assessment without specifying which sub-limb of Item 32 of the First Schedule of the Act that the respondent had invoked.

Held (dismissing the appeal with costs):

(1) When the Agreement was read as a whole, it was evident that the sale of the business consisting of the fixed assets, liabilities and business contracts were properties within the meaning in s 2 of the Act, and the intention of the parties was clearly to transfer these properties upon the sale to the appellant without the need for any further acts. Thus, the Agreement clearly fell within the second category of s 21(1) of the Act, which did not require an instrument to operate to convey or transfer property for it to be a conveyance on sale. The fact that the sale transaction was not concluded on the date of the instrument or that it was to be completed at a future date was immaterial, as the timing of the closing or when the title to the property passed could not be the determinant factor in construing whether an instrument was a conveyance on sale. Otherwise, ad valorem stamp duty could easily be avoided by merely stating in the instrument that the title to the property sold would pass at a future date. In fact, the introduction of s 59 of the UK Stamp Act 1891(which was in pari materia with s 21(1) of the Act) was to deal with and make an exception to the requirement in s 2 of the Act that such instruments must convey or transfer property before it could be chargeable with ad valorem duty. Thus, to that extent, the Court of Appeal had erred in holding that the Agreement was a conveyance on sale merely by virtue of the deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement, as it was a conveyance on sale irrespective of the said contractual deeming provision. With or without the contractual deeming provision, the Agreement fell squarely within s 21(1) of the Act and was thus to be construed as an actual conveyance on sale. (paras 55-57)

(2) The Court of Appeal, on the facts, fell into error when it said that the dictionary meanings of 'goods' in Black's Law Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary as advanced by the respondent, were of no assistance in the construction of that word as it appeared in s 21(1) of the Act. The dictionary meanings of the words 'goods', 'ware' and 'merchandise' clearly showed that they all referred to trading goods, which was very useful in determining the meaning of the word 'goods' and the intent of the legislature in using this specific word in s 21(1) of the Act. Further, similar construction applied with regard to the exemption given to agreements for sale of goods, wares and merchandise under exemption (a) of Item 4 of the First Schedule. The meaning of 'goods' therein also applied to the sale of goods in the course of trading, and not otherwise as contended by counsel for the appellant. Also, the term 'stock' found immediately after the words 'goods', 'wares' or 'merchandise' in s 21(1) did not refer at all to trading goods, but to shares in the capital stock or funded debt of a corporation, company, or society in Malaysia, as well as shares in the stocks or funds of the Government of Malaysia or any other Government or country. Hence, only trading goods would come under the exception to the second category of properties in s 21(1), while non-trading moveable properties would be chargeable with ad valorem duty under s 21(1) of the Act read with Item 32(a) of the First Schedule. Thus, the Court of Appeal had erred in that regard and its decision in that respect was reversed. (paras 73-76)

(3) The Federal Court in Pemungut Duti Setem lwn. Lee Koy Eng (Sebagai Pentadbir Bagi Harta Pusaka Tan Kok Lee @ Tan Chin Chai, Si Mati) laid down the principle that in determining a stamp duty appeal by way of Case Stated, the High Court's sole duty was to answer the question of law posed for its opinion. Hence, the High Court had no other duty but to answer the question put forth in the Case Stated. The issue regarding the non-specification of the sub-limb of Item 32 was not posed for determination in the Case Stated, thus the appellant was precluded from raising it. In any event, the appellant knew very well that the stamp duty assessment was made by the respondent under sub-Item (a) of Item 32 that provided for the imposition of ad valorem duty on the sale of any property, except for stock, shares, marketable securities and accounts receivables or book debts mentioned in sub-Item (c). The question put forth by the appellant in the Case Stated clearly pointed to Item 32(a) of the First Schedule, leaving no uncertainty as to which sub-item of Item 32 of the First Schedule applied to the Agreement. The stamp duty payable on the Agreement was assessed on the basis of a conveyance on sale, ie as sale or transfer of business, whereupon the only applicable provision was s 21(1) of the Act read together with Item 32(a) of the First Schedule. There was no other possible provision under Item 32 relating to ad valorem duty that could apply to the instrument other than sub-Item (a). All the other sub-Items on ad valorem duty had no possible connection or relevance to the instrument. Thus, the Agreement was treated as a conveyance on sale and clearly fell under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule, as it was an instrument specified with duty under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule, it could not be regarded as an instrument liable to duty under Item 4 of the First Schedule. (paras 77-80)

Case(s) referred to:

BASF Services (M) Sdn Bhd v. Pemungut Duti Setem [2010] 1 MLRA 317 (refd)

Capper & Anor v. Baldwin [1965] 2 QB 53 (refd)

Commissioners of Inland Revenue v. Angus [1889] 23 QBD 579 (refd)

Drages v. Commissioners of Inland Revenue [1927] 46 TC 389 (refd)

Farmer & Co v. IRC [1898] 2 QB 141 (refd)

Havi Logistics (M) Sdn Bhd v. Pemungut Duti Setem [2023] 2 MLRH 314 (refd)

Ipoh Garden Sdn Bhd v. Ismail Mahyuddin Enterprise Sdn Bhd [1975] 1 MLRH 517 (refd)

Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri v. Classic Japan (M) Sdn Bhd [2022] 4 MLRA 219 (refd)

Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri v. Rainforest Heights Sdn Bhd [2018] MLRHU 1869 (refd)

Maple Amalgamated Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Bank Pertanian Malaysia Berhad [2021] 5 MLRA 337 (refd)

Oughtred v. IRC [1960] AC 206 (refd)

Pemungut Duti Setem lwn. Lee Koy Eng (Sebagai Pentadbir Bagi Harta Pusaka Tan Kok Lee @ Tan Chin Chai, Si Mati) [2022] MLRAU 312 (refd)

Pemungut Duti Setem v. BASF Services (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [2009] 4 MLRA 161 (refd)

Pemungut Duti Setem v. Havi Logistics (M) Sdn Bhd [2024] 1 MLRA 241 (refd)

Pernas Securities Sdn Bhd v. The Collector of Stamp Duties [1976] 1 MLRH 546 (refd)

Stanway Limited v. Collector of Stamp Duties, Ipoh [1932] 1 MLRA 125 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Majlis Daerah Segamat [2022] 2 MLRA 334 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967, s 3

Stamp Act 1891 [UK], ss 54, 59

Stamp Act 1949, ss 2, 21(1), 38A, 39, First Schedule, Items 4, 32(a), (c)

Counsel:

For the appellant: S Saravana Kumar (Nur Hanina Mohd Azham & Melody Tham Cheng Yee with him); M/s Raj Ong & Yudistra

For the respondent: Normareza Mat Rejab (Mohammad Hafidz Ahmad, Syazana Safiah Rozman & Muhammad Danial Izzat Zulbahari with her); Inland Revenue Board of Malaysia

JUDGMENT

Vazeer Alam Mydin Meera FCJ:

Introduction

[1] This appeal concerns the issue of whether fixed or ad valorem stamp duty is payable under the Stamp Duty 1949 ("Act") on a commercial contract, namely, an Asset Purchase Agreement.

Background Facts

[2] On 6 February 2020, the appellant, Havi Logistics (M) Sdn Bhd, entered into an Asset Purchase Agreement ("the Agreement") with Martin-Brower Malaysia Co Sdn Bhd ("MB Malaysia") to purchase certain assets and liabilities.

[3] The principal operative clauses in the Agreement were cls 2.1(a) to (c). They read as follows:

2.1 Acquired Assets and Assumed Liabilities.

(a) Subject to and in accordance with the terms of this Agreement, the Seller hereby sells, transfers, conveys, assigns and delivers to the Purchaser, and the Purchaser hereby purchases from the Seller at the Closing, all of the Seller's right, title and interest in and to the Acquired Assets.

(b) Subject to and in accordance with the terms of this Agreement, the Purchaser hereby assumes as of and following the Closing, all of the Assumed Liabilities.

(c) Notwithstanding anything to the contrary herein, the Excluded Assets are excluded from the sale and purchase herein and shall be retained by the Seller.

[4] The details of the assets and liabilities acquired were set out in Schedule 1 and Schedule 3 of the Agreement. Schedule 1 specifies a listing of fixed assets (such as computer software, computer hardware, fittings, renovation, plant, machinery and equipment) and the inventory of the seller (which was to be determined as of the date of completion of the Agreement). Schedule 3 lists out a number of business contracts, the liabilities of which the appellant had agreed to assume under cl 2.1 (b) of the Agreement.

[5] There were some assets excluded from the sale transaction and these were listed under Schedule 2 of the Agreement. Among others, the "goodwill of the Malaysia Business" of MB Malaysia was excluded.

[6] The consideration payable for the transaction was specified under cl 2.2(a) of the Agreement, which reads as follows:

The purchase price for the Acquired Assets (save for Inventory which shall be dealt with in cl 2.2(c)) of this Agreement and Assumed Liabilities is USD2,491,491.55 ("Purchase Price") payable in cash by the Purchaser on Closing to the Seller or as directed by the Seller.

The USD2,491,491.55 was equivalent to RM10,378,806.35 at the then-prevailing exchange rate.

[7] According to cl 1 of the Agreement, the Closing Date shall mean 31 March 2020 or such other date for the Closing of the Transaction as agreed in writing by the parties.

[8] The appellant through their solicitors applied to the respondent on 5 March 2020 for assessment of stamp duty payable on the Agreement. The respondent assessed the Agreement with ad valorem duty of RM399,196.00 on the basis that the Agreement fell within the ambit of s 21(1) of the Act, and Item 32 of the First Schedule to the Act ("Assessment"). The appellant made a payment of RM399,196.00 to the respondent under protest with a notice of objection as required under s 38A of the Act.

[9] On 11 April 2020, the appellant lodged an appeal against the Assessment on grounds that the Agreement should be assessed based on Item 4, First Schedule of the Act, wherein only a fixed stamp duty of RM10.00 was payable. The respondent rejected the appellant's appeal via letter dated 13 April 2020 and maintained the earlier decision dated 15 March 2020 to impose ad valorem duty on the instrument.

[10] Aggrieved by the respondent's decision, the appellant appealed to the High Court by way of a Case Stated pursuant to s 39 of the Act. The High Court allowed the appellant's appeal and ordered, among others, that:

(a) the Notice of Stamp Duty Assessment (Ad Valorem Duty) dated 15 March 2020 issued by the respondent be set aside on the basis that it was erroneous, null, and void;

(b) the applicable stamp duty chargeable on the Agreement is only RM10.00; and

(c) the excess stamp duty paid amounting to the sum of RM399,186.00 be refunded to the appellant.

[11] The respondent appealed against the High Court's decision to the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal allowed the respondent's appeal and the respondent's Assessment imposing ad valorem duty under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Act was upheld. The Court of Appeal's rationale for the decision may be summarized as follows:

(a) The title of the Acquired Assets under the Agreement was passed to the respondent under the Agreement by virtue of the contractual deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement. Hence, the Agreement constituted a conveyance on sale under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule.

(b) The Agreement does not come within s 21(1) of the Act as the fixed assets that were sold under the Agreement came within the meaning of 'goods', which is an exception under the said provision.

Leave To Appeal

[12] The appellant being dissatisfied with the decision of the Court of Appeal, applied for, and the Federal Court granted leave to appeal, on the following questions of law:

(a) Whether the Asset Purchase Agreement was a conveyance on sale within the meaning of s 21(1) of the Stamp Act 1949 which is dutiable under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Stamp Act 1949.

(b) Whether the deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Asset Purchase Agreement makes the said agreement an instrument (ie conveyance on sale) which falls under s 21(1) of the Stamp Act 1949.

(c) Whether the Asset Purchase Agreement falls under the exception under s 21(1) of the Stamp Act 1949 and if the answer is in the affirmative, was the Court of Appeal correct to subject the said Agreement to ad valorem duty under Item 32(a) of First Schedule of the Stamp Act 1949.

(d) Whether the Collector of Stamp Duties may raise a stamp duty assessment without specifying which sub-limb of Item 32 of the First Schedule of the Stamp Act 1949 that the Collector has invoked?

Proceedings At The High Court

[13] The learned High Court Judge quite correctly ruled that the sole issue to be determined was whether the stamp duty on the Agreement is to be assessed under Item 4 or Item 32, First Schedule of the Act.

[14] Instruments that came under Item 4 of the First Schedule of the Act are described as:

AGREEMENT OR MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT made under hand only, and not otherwise specially charged with any duty, whether the same is only evidence of a contract or obligatory on the parties from its being a written instrument.

[15] Whilst instruments that fell under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Act are described as:

CONVEYANCE, ASSIGNMENT, TRANSFER OR ABSOLUTE BILL OF SALE:

(a) On sale of any property (except stock, shares, marketable securities and accounts receivables or book debts of the kind mentioned in paragraph (c))

[16] If an instrument came under Item 4, then the stamp duty payable is the fixed RM10.00, but if it was chargeable under Item 32(a) then ad valorem duty shall be payable calculated in the following manner:

For every RM100.00 or fractional part of RM100.00 of the amount of the money value of the consideration or the market value of the property, whichever is the greater:

(i) RM1.00 on the first RM100,000.00;

(ii) RM2.00 on any amount in excess of RM100,000.00 but not exceeding RM500,000.00;

(iii) RM3.00 on any amount in excess of RM500,000.00 but not exceeding RM1,000,000.00;

(iv) RM4.00 on any amount in excess of RM1,000,000.00.

[17] The appellant submitted that the Agreement came under Item 4 of the First Schedule, and thus only the fixed RM10.00 was payable. The respondent, on the other hand, contended that the Agreement is a conveyance of interest in the property of MB Malaysia to the appellant, and thus, it fell under Item 32 of the First Schedule read together with s 21 of the Act which attracted ad valorem duty payable by the appellant as the purchaser.

[18] Section 21 of the Act states that:

Certain contracts to be chargeable as conveyances on sale

21. (1) Any contract or agreement made in Malaysia under seal or underhand only, for the sale of any equitable estate or interest in any property whatsoever, or for the sale of any estate or interest in any property except lands, tenements. hereditaments, or heritages, or property locally situate out of Malaysia, or goods, wares or merchandise, or stock, or marketable securities, or any ship or vessel, or part interest, share or property of or in any ship or vessel, shall be charged with the same ad valorem duty, to be paid by the purchaser, as if it were an actual conveyance on sale of the estate, interest or property contracted or agreed to be sold.

[Emphasis Added]

And s 2 of the Act defines "conveyance on sale" and "property" as follows:

"conveyance on sale" includes every instrument and every decree or order of any Court, whereby any property, or any estate or interest in any property, upon the sale thereof is transferred to or vested in a purchaser or any other person on his behalf or by his direction.

"property" includes movable or immovable property and any estate or interest in any property moveable or immovable, whether in possession, reversion, remainder or contingency, and any debt, and anything in action, and any other right or interest in the nature of property which is capable of being disposed of and has a value in it."

[19] The term "movable property" is not defined under the Act. According to s 3 of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967, "movable property" means all property other than immovable property whilst "immovable property" is defined to include land, benefits to arise out of land, and things attached to the earth or permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth.

[20] The learned High Court Judge in the grounds of judgment had found as follows:

[13] The instrument in question herein is the Agreement between the Plaintiff and MB Malaysia which is a written contract for the sale and purchase of business excluding the goodwill (see s 2 of the Agreement which stipulates that the goodwill of the MB Malaysia business in Malaysia is excluded from the transaction).

[14] Having conceded that goodwill of MB Malaysia is excluded from the transaction, the Respondent takes the position that the Agreement involves conveyance on the interest on property of MB Malaysia to the Plaintiff and thus, falls under s 21 and Item 32, First Schedule of the SA.

......

[20] Based on the Agreement, the fact that goodwill is not part of the "Acquired Assets" and that there is no landed property involved, it is of the considered view that the business contract between MB Malaysia and the Plaintiff does not involve transfer of properties or interest legally or equitably between the two parties. As such, the Agreement cannot be said to be an instrument which falls within the purview of s 21 and Item 32, First Schedule of the SA.

[21] Ad valorem duty can only be imposed when a property is legally or equitably transferred by an instrument....

[21] The learned High Court Judge, in short, found the Agreement does not involve the transfer of properties or interest legally or equitably between the appellant and MB Malaysia, and as such it was not an instrument that fell within the purview of s 21 and Item 32 of the First Schedule to the Act. In this regard, the learned judge further referred to the "Malaysian Stamp Duty Handbook" Sixth Edition by Dr Arjunan Subramaniam and also the cases of Commissioners of Inland Revenue v. Angus [1889] 23 QBD 579 referred to by Thorne J, Acting CJ in Stanway Limited v. Collector of Stamp Duties, Ipoh [1932] 1 MLRA 125 for the proposition that where a property is legally or equitably transferred by an instrument the stamp duty is ad valorem, but if an instrument does not transfer property legally or equitably then it is merely a contract (as opposed to a conveyance) and no ad valorem duty is payable. In Angus, the matter was put this way:

If the property is legally or equitably transferred by the instrument to which a stamp ought to be affixed, then, no doubt, ad valorem duty ought to be paid upon an agreement but if by an instrument no property is legally or equitably transferred, then it falls within the ordinary denomination of deeds and is simply to be stamped with an ordinary stamp, and no ad valorem duty would be payable until after the conveyance was actually made in pursuance of the agreement. The question is, whether this agreement can be said to convey or transfer any legal or equitable interest.

Hence, the instrument in Angus was held to be an executory contract and not a conveyance on sale because the transaction was incomplete at the time when the instrument was executed. In Angus, the completion date was a future date.

[22] Similarly, in Stanway Limited (supra), the material terms of the agreement were that the sale was to be completed when the consideration was to be paid and satisfied, and the vendors were to execute and do all such assurances and things as should be reasonably required by the purchasers for the vesting in them of the said premises so sold. Upon the presentation of the agreement, the Collector of Stamp Duty in that case was of the opinion that under the provisions of the Stamp Enactment ad valorem duty was payable on the total consideration and an amount of that duty was assessed. Thorne Acting CJ held as follows:

With regard to the contention raised by the Government here as to the operation of this agreement, I would refer to the passage in the judgment of Hawkins J., at the bottom of p 128, where he says:

"If the property is legally or equitably transferred by the instrument to which a stamp ought to be affixed, then, no doubt, an ad valorem duty ought to be paid upon an agreement, but if by an instrument no property is legally or equitably transferred, then it falls within the ordinary denomination of deeds and is simply to be stamped with an ordinary stamp, and no ad valorem duty would be payable until after the conveyance was actually made in pursuance of the agreement. The question is, whether this agreement can be said to convey or transfer any legal or equitable interest."

... it is quite clear that this contract of sale contemplates a completion of purchase, acts remained to be done, and instruments remained to be executed, in order to carry the agreement into effect.

This instrument is a concluded agreement between the parties, and is not a conveyance on sale, and further assurances are necessary in order that it may become a completed purchase. The practical test, as I have said, applied to a question of this kind is to ask oneself the question as to what would happen if either of the parties failed to complete the purchase. The answer, as I have pointed out, is that the effect and operation of this document is to create in the purchasers a right of action ex contractu.

I am of the opinion, therefore, that the decision of the Collector, of the Chief Revenue Authority, and the Judge in the Court below are all wrong, and that this instrument should be stamped under Schedule A of the Stamp Enactment with a 25 cents stamp.

[23] The learned High Court Judge further considered the issue of the respondent's failure to specify which sub-item of Item 32, First Schedule of the Act was relied on to impose the ad valorem duty as well as reasons as to the imposition of the duty. Thus, by reference to the case of Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri v. Rainforest Heights Sdn Bhd [2018] MLRHU 1869, the learned judge held that the notice of assessment issued by the respondent was bad.

[24] Thus, the learned High Court Judge concluded as follows:

"[47] The facts are clear. The Agreement is a mere written contract for the purchase of business between the Plaintiff and MB Malaysia and the consideration paid by the Plaintiff is for the list of assets stated in the Agreement. The Agreement clearly stipulates that the goodwill of MB Malaysia's business in Malaysia is excluded from the transaction and that MB Malaysia remains in business in Malaysia. The Agreement is not a sham arrangement. Nowhere can it be shown that the valuation of the assets purchased by the Plaintiff is inflated.

[48] On a plain reading of Item 4, First Schedule of the SA, this Court finds that the Plaintiff has fulfilled all the requirements stipulated thereunder. The Agreement clearly fell within the ambit of Item 4, First Schedule of the SA. Therefore, the stamp duty on the Agreement should be assessed under the same Item".

See: Havi Logistics (M) Sdn Bhd v. Pemungut Duti Setem [2023] 2 MLRH 314 for the Judgment of the High Court.

Proceedings At The Court of Appeal

[25] The respondent's main grounds of appeal were that the stamp duty for the Agreement should have been assessed in reference to s 21(1) of the Act read together with Item 32(a) to the First Schedule of the same Act.

[26] Hence, the core issues that arose were:

(i) whether the Agreement was a 'conveyance on sale' within the meaning of s 2 of the Act, thus being chargeable with ad valorem duty; and

(ii) whether the fixed assets (part of the acquired assets) sold under the Agreement fell within the expression 'goods' as mentioned under s 21(1) of the Act, thus exempted from the operation of the said section and not attracting ad valorem duty.

[27] The Court of Appeal reversed the decision of the High Court and allowed the appeal on grounds that the Agreement was a conveyance on sale within the meaning of the Act, thus attracting ad valorem duty.

[28] The grounds of judgment of the Court of Appeal may be summarized as follows:

"(i) Clause 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement stated that at closing, the title and risk in the acquired assets would pass automatically through a deeming provision. The assets were deemed delivered where they were located, with no further action required by the parties. Thus, the Agreement itself should serve as the instrument by which title passed, which meant that it was a 'conveyance on sale' under the Act, and was thus subject to duty under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule.

(ii) However, contrary to the respondent's assertion, the Court of Appeal found that the fixed assets (part of the acquired assets) sold under the Agreement fell within the expression of 'goods' as mentioned under s 21(1) of the Act. Hence, the Court held that the Agreement was excepted from the operation of the said s 21, and did not attract ad valorem duty.

(iii) The term 'goods' typically refers to tangible property. Black's Law Dictionary defines it as 'tangible or movable personal property other than money.' The Court of Appeal did not find reasons to narrow this to only current assets or inventory held by a company. Section 21(1) of the Act applies generally and does not suggest a distinction between capital goods and inventory. The Oxford English Dictionary, cited by the appellant, defines goods as 'property' or 'merchandise, wares,' but the Court saw no reason to favour one definition over the other. The appellant argued that 'goods' should be read in line with 'wares or merchandise,' meaning only those held for future sale, excluding capital goods. However, no authority supported this claim.

(iv) In Drages v. Commissioners of Inland Revenue [1927] 46 TC 389, the UK tax authorities did not distinguish between goods held as inventory and those held as capital ( e.g. motor lorries or office furniture) under s 59 of the Stamp Act 1891. All were treated as part of the 'goods, wares, or merchandise' exception. Therefore, the court concluded that the fixed assets sold under the agreement fell under the meaning of 'goods' in s 21(1) of the Act. As a result, the consideration for the fixed assets was not subject to ad valorem duty due to s 21(1)".

[29] Despite that finding, the Court of Appeal nevertheless went on to hold that the Agreement was a conveyance on sale within the definition in s 2 of the Act due to the presence of the contractual deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement which states that the title to the assets were deemed have passed and delivered at the place where they were located. On that basis, the Court of Appeal held that the Agreement was a conveyance on sale that attracted ad valorem duty as it fell under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Act.

[30] Clause 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement read as follows:

"(c) As of and at Closing:

(i) title to the Acquired Assets and all risk of loss as to the Acquired Assets shall be deemed to have passed to the Purchaser and deemed delivered at the place at which the Acquired Assets are located; and"

Hence, the Court of Appeal held that by virtue of this contractual deeming provision, no separate act was to be undertaken by parties for the transfer of legal title for the assets and that the Agreement was thus the instrument by which title to the assets passed to the purchaser, without anything more.

See: Pemungut Duti Setem v. Havi Logistics (M) Sdn Bhd [2024] 1 MLRA 241 for the full judgment of the Court of Appeal.

The Decision Of This Court

(a) Applicable Principles

[31] A good starting point would be to look at the applicable legal principles. This Court has in BASF Services (M) Sdn Bhd v. Pemungut Duti Setem [2010] 1 MLRA 317 reiterated the principle that stamp duty is chargeable on an instrument and not on the transaction. The reason is quite simple. Under the Act, stamp duty is imposed on an instrument and not on a transaction. Hence, if the transaction can be effected orally or by conduct, it would not attract stamp duty. Thus, one must look at the instrument in determining the applicable stamp duty. See: Pernas Securities Sdn Bhd v. The Collector of Stamp Duties [1976] 1 MLRH 546; Pemungut Duti Setem v. BASF Services (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [2009] 4 MLRA 161.

[32] In construing the Act and the First Schedule thereto, it must be borne in mind that legislative intent must be given effect to and the function of the court is to interpret the statute 'according to the intent of them that made it and the intention must be deduced from the language used' (per Lord Parker CJ in Capper & Anor v. Baldwin [1965] 2 QB 53 at p 61).

[33] In BASF Services (Malaysia) (supra), this Court had further elaborated on the legislative scheme of Item 32(a), First Schedule, and in particular what instruments come to be regarded as 'conveyance on sale'. The Court said:

"[10] Under the First Schedule, with particular reference to item 32(a), an instrument purporting to convey real estate is liable to duty as it falls under conveyance on sale. With the definition of instrument being so wide under s 2 of the Act, which includes every written document, the ventilation by the appellant that the transfer form is the chargeable instrument is a reasonable option, as the second part of the definition of instrument requires the transfer or the vesting of property to the purchaser. The appellant pressed on, in order to arrive at a negative answer to the question for determination that the agreement, did not operate to transfer the property to it. In his submission, the appellant canvassed that only the transfer form will transfer the property, due to the words in the impugned item. With the infrastructure fee also not included in the transfer form, which means less stamp duty being chargeable, it is no surprise too that the appellant chose this option.

[11] Sir Nathaniel J Highmore in "The Stamp Laws" 4th edn at p 160 had occasion to write:

"It is not necessary that a conveyance on sale should be preceded by a contract of purchase and sale, and where a conveyance is made from one person to another for money or what is according to the provisions of the Stamp Act the equivalent of money, the instrument is a conveyance on sale".

[Emphasis Added]

[12] In Furness Railway Company v. The Commissioners of Inland Revenue [1864] 33 LJ Exch 173 the court held that a transfer of the undertaking of a railway company to another railway company by deed for similar considerations was chargeable with ad valorem duty. In Chesterfield Brewery Company v. Commissioners of Inland Revenue [1899] 2 QB 7 an agreement was executed whereby all shareholders in a company in the course of being voluntarily wound up agreed to exchange their shares in the company for shares in a new company then incorporated. There was a proviso that after the allotment of the shares in the new company, the shareholders in the old company would hold their shares in the old company in trust for the new company. The agreement was held to be a conveyance on sale and thus subject to ad valorem duty.

[13] Returning to s 2 of the Act, conveyance on sale "includes every instrument and every decree or order of any court, whereby any property, or any estate or interest in any property, upon the sale thereof is transferred to or vested in a purchaser or any other person on his behalf or by his direction;". Under this provision, any transfer of any estate or interest in any property thus can take place by an order or decree of any court without more but this is a statutory concession (see also ss 18 and 23 of the Act).

[14] It is obvious as gauged from the above precedents and authorities, a deed, agreement, Act or some documentary medium may be chargeable to ad valorem stamp duty, but subject to the instrument being able to transfer title. Therefore, property may be transferred by other means, legally or equitably and not necessarily only via the process of a transfer form. Much depends on the facts of each case.

[15] Having considered the submissions of parties, in the circumstances of the case, we agree with the appellant that the transfer form is the instrument that should attract stamp duty. This is so as the agreement of 11 October 1997 does not have the legal effect of transferring the property to the appellant. Here, in order for the transfer of property to be effective there is another step to be undertaken by the appellant ie, the filing of the transfer form, and unless duly stamped the transfer of property falls short of one step. Lord Esher MR had occasion to explain in Commissioners of Inland Revenue v. Angus [1889] LR 23 QBD 579:

The taxation is confined to the instrument whereby the property is transferred. The transfer must be made by the instrument. If a transfer requires something more than an instrument to carry it through, then the transaction is not struck at, and the instrument is not struck at because the property is not transferred by it.

[16] The agreement here therefore is merely a contract to convey rather than a conveyance of the property to the appellant (Malaysian Stamp Duty Handbook 4th edn by Arjunan Subramaniam; Stanway Limited v. Collector Of Stamp Duties Ipoh [1931] 1 MLRA 435; [1931-32] FMSLR 239)"

[34] The Court of Appeal quite correctly summarised the applicable principles in assessing the duty payable on an instrument in the following manner.

"[63] We summarise the applicable principles as follows:

(i) the first step in assessing the duty payable in respect of an agreement for the sale of the property is to determine whether the sale relates to an equitable estate or equitable interest in the property. If it is, then the duty payable would be at the ad valorem rate specified under Item 32 of the First Schedule;

(ii) if, on the other hand, the agreement relates to a sale of a legal estate or legal interest in the property, then it must be ascertained if any of the exceptions in s 21(1) apply. If they do not, then duty would be payable ad valorem pursuant to Item 32 of the First Schedule;

(iii) if however the sale relates to legal estate or legal interest in the property, and the property in question comes within one of the exceptions in s 21(1), the next question to be asked is whether the agreement or contract in question is a conveyance on sale. Does property in assets pass to the purchaser by virtue of the agreement or contract in question? If so, then duty would be payable ad valorem pursuant to Item 32 of the First Schedule;

(iv) if, on the other hand, one of the exceptions applies and the agreement is on its proper construction not a conveyance on sale, then the agreement or contract ought to be stamped as an "agreement" pursuant to Item 4 of the First Schedule of the Stamp Act 1949".

(b) The Issues In This Appeal

Issue (i): Whether The Agreement Was A 'Conveyance On Sale' Within The Meaning Of Section 2 Of The Act, Thus Being Chargeable With Ad Valorem Duty

[35] The appellant contended that the Agreement is a mere written contract for the purchase of business between the appellant and MB Malaysia for which stamp duty is the fixed RM10.00 under Item 4 of the First Schedule to the Act. The appellant further submitted that there is no conveyance, assignment, or transfer of the sale of property under the Agreement that would warrant the application of Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Act. The respondent contended otherwise.

[36] In ascertaining whether the Agreement was a conveyance on sale, the court must first determine whether the intention of the parties to the agreement is to ultimately pass title to the assets to the appellant via the instrument. Here, the sale of the business from MB Malaysia to the appellant consisted of the fixed assets, liabilities and business contracts stipulated in the Agreement.

[37] The Court of Appeal did not reject the respondent's contention that the Agreement fell under s 21(1) of the Act, but rather found that the fixed assets under the Agreement came within the expression 'goods' in the said s 21(1), and thus, excluded from ad valorem duty. This is found in para 62 of the Court of Appeal's Judgment:

"[62] For this reason, we were fortified in our view that the fixed assets sold under the asset purchase agreement in the present case came within the meaning of "goods" within the meaning of s 21(1) of the Stamp Act 1949. Accordingly the consideration paid for the fixed assets would not be dutiable on an ad valorem basis, by reason solely of s 21(1). Nonetheless, the asset purchase agreement constituted a "conveyance on sale" of the fixed assets, because - as explained at paras [28] and [29] ante - the property in the fixed assets passed to the respondent by the asset purchase agreement without the need for any further act to be taken by the parties to the agreement".

And paras 28 and 29 of the Judgment read:

"[28] Clause 2.3(c)(i) provides that as at closing, title to and risk in the acquired assets passed automatically by way of a deeming provision, and such assets were deemed delivered where they are located. The asset purchase agreement did not contemplate any separate act to be undertaken by the parties for the transfer of legal title. For this reason, the asset purchase agreement must be the instrument by which title to the acquired assets passed. The agreement supported no other reasonable construction.

[29] That being the case, the asset purchase agreement constituted a conveyance on sale within the meaning of the Stamp Act 1949 and would be dutiable pursuant to Item 32(a) of the First Schedule. For this reason, we must allow the appeal by the Collector of Stamp Duty".

[38] Thus, the Court of Appeal held that the Agreement was subject to ad valorem duty under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Act for the following reasons:

(i) Clause 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement states that as of and at closing title to the assets shall be deemed to have passed to the appellant and deemed delivered where they are located; and

(ii) No separate act was to be undertaken by parties for the transfer of legal title for the assets. The Agreement is the instrument by which the title to the assets is passed; and

(iii) The instrument that falls within the ambit of s 21(1) is not in itself an instrument of conveyance but due to the deeming words in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement, the instrument has to be treated as a conveyance on sale, and thus became dutiable ad valorem under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule.

[39] We agree with the Court of Appeal that the Agreement is a conveyance on sale, as it falls within the definition provided in s 2 of the Act. However, we do not agree with the Court of Appeal's view that the Agreement, though falling within the ambit of s 21(1) of the Act is not in itself an instrument of conveyance on sale, but becomes one only by virtue of the deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement.

[40] As stated earlier the expression "conveyance on sale" is defined in s 2 in the following manner:

"Conveyance on sale includes every instrument and every decree or order of any Court, whereby any property, or any estate or any interest in any property, upon the sale thereof is transferred to or vested in a purchaser or any other person on his behalf or by his direction".

The statutory definition of 'conveyance on sale' makes it clear that an instrument by which property or any interest therein is transferred on the sale of such property or interest would be regarded as a conveyance on sale. This definition of conveyance on sale is similar to that of s 54 of the Stamp Act 1891 of England & Wales, upon which our Act is based.

[41] In Oughtred v. IRC [1960] AC 206, Lord Denning explained the effect of s 54 in the following terms:

"In my opinion, every conveyance or transfer by which an agreement for sale is implemented is liable to stamp duty on the value of the consideration... Suffice it that the instrument is the means by which the parties choose to implement the bargain they have made. It is then a "conveyance or transfer on sale" of any property which I take to mean a conveyance or transfer consequent upon the sale of any property and in implementation of it".

[Emphasis Added]

[42] Now, when the Agreement is scrutinised carefully, it would fall squarely within the definition in s 2 of the Act. The Agreement is essentially for the sale and purchase of a business, excluding goodwill. Clause 2.1(a) of the Agreement clearly stated that the seller, MB Malaysia, was to sell, transfer, convey, assign and deliver to the appellant all of MB Malaysia's right, title and interest in the Acquired Assets.

[43] 'Acquired Assets' is defined under cl 1.1 of the Agreement as follows:

"Acquired Assets" means business assets of the Seller related to the Malaysia Business (excluding the Excluded Assets), particulars of which are set out in Schedule 1 and Schedule 3."

Whilst, 'Malaysia Business' is defined to mean:

"business carried on by the Seller related to the Malaysia market and McDonald's markets listed in cl 2.1 (j)".

[44] As stated earlier, what was agreed to be sold and transferred were the Acquired Assets, the particulars of which are contained in Schedule 1 and Schedule 3. Schedule 1 consists of (1) Fixed Assets, (2) Inventory (3) Liabilities under Business Contracts, and (4) Liabilities related to the Acquired Assets (if any). Clause 2.1(b) of the Agreement provides that the appellant as the purchaser will assume the business liabilities of the seller, which is termed as the 'Assumed Liabilities'.

[45] Apart from the above, Acquired Assets also consist of Business Contracts, which particulars were listed in Schedule 3. Clause 2.1(e) of the Agreement stipulated that the appellant will assume and undertake to perform the Business Contracts and be bound by their terms. These Business Contracts included:

(1) Contracts for hire or lease of equipment, including without limitation, material handling equipment, floor cleaning equipment and spare parts for these equipment.

(2) Contracts for facilities, tenancy or lease of Properties used for the Malaysia Business, save for the IT Office Lease.

(3) Contracts for IT related services.

(4) Contracts for photocopiers.

(5) Contract for truck hires.

(6) Contracts for provision of other third party services.

(7) Deposits.

[46] Further, cl 2.1(j) of the Agreement provides that the appellant shall take over the service of supplying McDonald's products to a number of McDonald's markets overseas, which charge will be based on the current markup charged by MB Malaysia.

[47] Hence, the sale and purchase of the business under the Agreement consisted of:

(i) Transfer of the fixed assets (including inventories) to the appellant;

(ii) The appellant assuming the rights and liabilities of the Business Contracts and Acquired Assets; and

(iii) The appellant taking over the Business Contracts, including the supply of products to McDonald's markets overseas.

[48] The consideration for the sale and transfer of the Acquired Assets and Assumed Liabilities is provided in cl 2.2(a) of the Agreement:

"The purchase price for the Acquired Assets (save for Inventory which shall be dealt with in cl 2.2(c) of this Agreement and Assumed Liabilities is USD2,491,491.55 ("Purchase Price") payable in cash by the Purchaser on Closing to the Seller or as directed by the Seller".

Further, cl 2.2(b) apportioned the purchase price in the manner set out in Schedule 1. Even though the purchase price in Schedule 1 was aligned to the fixed assets, the consideration was in actual fact for the sale of the business consisting of the fixed assets (excluding the inventories that were computed separately), the assumed liabilities and the business contracts. This was reflected in the respondent's explanation in the Case Stated at para 15.13(i), (ii) and (iii). Thus, the respondent had assessed the ad valorem duty on the whole consideration.

[49] Apart from this, the Agreement provided under cl 2.3(c)(i) that at the Closing, the title to the Acquired Assets shall be deemed to have passed to the respondent and deemed delivered at the place the Acquired Assets were located. "Closing" was defined in cl 1.1 as the closing of the Transaction. "Transaction" is further defined as "the sale and transfer by the Seller and the purchase and assumption by Purchaser of the Acquired Assets and the Assumed Liabilities".

[50] Now, it would be opportune to look at s 21(1) of the Act, and it reads:

"Certain contracts to be chargeable as conveyances on sale.

21.(1) Any contract or agreement made in Malaysia under seal or under hand only, for the sale of any equitable estate or interest in any property whatsoever, or for the sale of any estate or interest in any property except lands, tenements, hereditaments, or heritages, or property locally situate out of Malaysia, or goods, wares or merchandise, or stock, or marketable securities, or any ship or vessel, or part interest, share or property of or in any ship or vessel, shall be charged with the same ad valorem duty, to be paid by the purchaser, as if it were an actual conveyance on sale of the estate, interest or property contracted or agreed to be sold".

[51] Hence, an instrument, though not a conveyance on sale as defined in s 2 of the Act, would be chargeable with ad valorem duty under s 21(1) of the Act as if it was an actual conveyance on sale if it fulfils the following criteria:

(a) The instrument is a contract or agreement.

(b) The contract or agreement is for (i) the sale of equitable estate or interest in any property, or (ii) the sale of any estate or interest in any property.

(c) If the agreement is for the sale of estate or interest in property ie under category para (b)(ii) above, the following are excluded from ad valorem duty, namely if the instrument is in respect of an agreement for the sale of:

(i) lands, tenements, hereditaments;

(ii) heritages;

(iii) property locally situated out of Malaysia;

(iv) goods, wares or merchandise;

(v) stock;

(vi) marketable securities;

(vii) any ship or vessel; or

(viii) part interest, share or property of or in any ship or vessel.

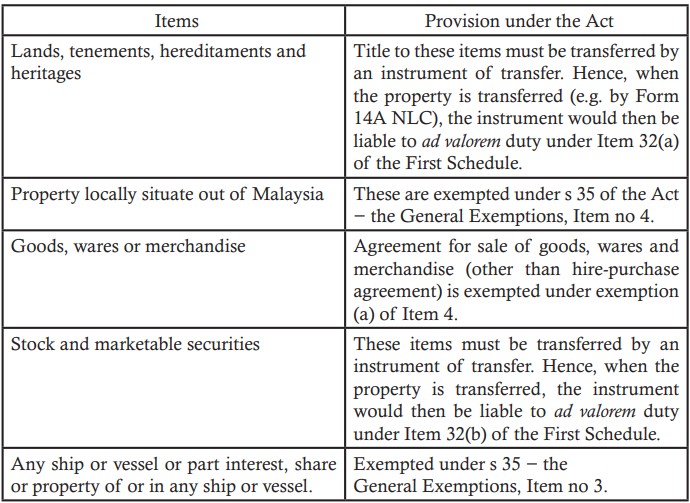

[52] The items in para [51](c)(i) to (vii) above were specifically excluded from ad valorem duty under s 21(1) as stamp duty provisions for those items were catered for in other provisions of the Act, as follows:

[53] Thus, the Court of Appeal had quite correctly stated that s 21(1) of the Act applies to two categories of contracts or agreements, namely (i) first, a contract or agreement for sale of equitable estate or equitable interest in any property, and (ii) second, a contract or agreement for sale of legal estate or legal interest in any property. The first category would not be subject to any exclusions, whilst the second category, would. See: Farmer & Co v. IRC [1898] 2 QB 141. Hence, if the instrument comes under either category in s 21(1) of the Act, and if the exclusion did not apply, then it shall be treated as conveyance on sale and ad valorem duty shall apply. The Court of Appeal, had, by reference to the English position, quite correctly stated this in para 46 of the Judgment in the following terms:

"[46] More significant is the introduction of s 59. On its plain reading, it removes the previous requirement that an instrument must operate to convey or transfer property before it becomes chargeable with ad valorem duty. The net is now cast wider, to encompass all contracts for the sale of an estate or interest in property, regardless of whether such contract operates as an instrument of conveyance. Where however the contract relates to the sale of a legal estate or interest, there are exceptions for certain classes of property, namely real property, tenements, hereditaments, heritages, property located outside the jurisdiction, goods, wares or merchandise, stock, marketable securities, ships and vessels. For these classes of assets exempt from the operation of s 59, s 54 applies. Thus, a contract for the sale of goods would only be dutiable ad valorem if it operated as a conveyance on sale".

[Emphasis Added]

[54] Learned counsel for the appellant relied on Commissioners Of Inland Revenue v. Angus [1889] 23 QBD 579, where the instrument in issue was held to be an agreement and not a conveyance on sale because the transaction was not completed at the time when the instrument was executed. The completion date was a future date. Thus, the appellant contended that similarly the Agreement was not chargeable with ad valorem duty as the transaction therein was not completed at the time when the instrument was executed, and that the closing was at a future date. We are unable to accept this argument for the simple reason that the principle enunciated in Angus was no longer applicable following the statutory introduction of s 59 to the UK Stamp Act, as was noted by the Court of Appeal in para 46 of its Judgment:

.. it removes the previous requirement that an instrument must operate to convey or transfer property before it becomes chargeable with ad valorem duty. The net is now cast wider, to encompass all contracts for the sale of an estate or interest in property, regardless of whether such contract operates as an instrument of conveyance.

[55] Now, when the Agreement is read as a whole, it is evident that the sale of the business consisting of the fixed assets, liabilities and business contracts were properties within the meaning in s 2 of the Act, and the intention of the parties is clearly to transfer these properties upon the sale to the appellant without the need for any further acts on the part of the parties. Thus, the Agreement clearly falls within the second category of s 21(1) of the Act.

[56] There is no requirement under s 21(1) of the Act that an instrument must operate to convey or transfer property for it to be a conveyance on sale. The fact that the sale transaction was not concluded on the date of the instrument or that it was to be completed at a future date is immaterial. The timing of the closing or when the title to the property passes cannot be the determinant factor in construing whether an instrument is a conveyance on sale. Otherwise, ad valorem stamp duty can easily be avoided by merely stating in the instrument that the title to the property sold shall pass at a future date. In fact, the introduction of s 59 of the UK Stamp Act 1891 (which is in pari materia with our s 21(1) of the Act) was to deal with and make an exception to the requirement in s 2 of the Act that such instruments must convey or transfer the property before it can be chargeable with ad valorem duty.

[57] Thus, to that extent, we are of the view that the Court of Appeal had erred in holding that the Agreement was a conveyance on sale merely by virtue of the deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement. The Agreement is a conveyance on sale irrespective of the said contractual deeming provision. The Agreement, with or without the contractual deeming provision in cl 2.3(c) (i) of the Agreement, falls squarely within s 21(1) of the Act and is thus to be construed as an actual conveyance on sale.

Issue (ii): Whether The Fixed Assets (Part Of The Acquired Assets) Sold Under The Agreement Fell Within The Expression 'Goods' As Mentioned Under Section 21(1) Of The Act, Thus Excluded From The Operation Of The Said Section And Not Attracting Ad Valorem Duty

[58] The Court of Appeal ruled that though the Agreement came within the ambit of the second category of s 21(1) of the Act, it was excluded because it viewed the fixed assets sold and transferred under the Agreement to come within the expression of "goods", and therefore, excluded from the operation of the said section. The operative part of s 21(1) of the Act dealing with the exception provides as follows:

"... except lands, tenements, hereditaments, or heritages, or property locally situate out of Malaysia, or goods, wares or merchandise, or stock, or marketable securities, or any ship or vessel, or part interest, share or property of or in any ship or vessel..."

[59] Learned counsel for the appellant submits that the Court of Appeal was correct in holding that the fixed assets sold under the Agreement came within the meaning of 'goods' in s 21(1) of the Act, and thus the instrument is excluded from ad valorem duty.

[60] The learned Senior Revenue Counsel, on the other hand, submitted that the fixed assets listed in the Agreement would not come within the meaning of "goods, wares or merchandise" under s 21(1) of the Act. This is based on the argument that the term 'goods' was only intended to cover stock-in-trade or assets held as inventory. The respondent further contended that capital assets such as tables, chairs and computer equipment sold under the Agreement would not fall under the exception under s 21(1) of the Act, and thus, the Agreement would be regarded as a conveyance on sale chargeable with ad valorem duty.

[61] The Court of Appeal disagreed with the stance taken by the Senior Revenue Counsel as can be seen in paras 48 to 62 of the Judgment of the Court of Appeal. In coming to that decision, the Court of Appeal had in the main referred to the English case of Drages v. Commissioners of Inland Revenue [1927] 46 TC 389, and considered the position taken by the courts in England in construing the meaning of the word 'goods' in their equipollent s 59 of the Stamp Act 1891, and concluded as follows:

"[61] It is thus apparent that the Commissioners of Inland Revenue of the UK, in implementing s 59 of the Stamp Act 1891, did not discriminate between goods held as inventory or stock, and goods that were capital in nature (such as motor lorries and office furniture). They treated all of these as coming within the exception of "goods, wares or merchandise". This then is the reason why no dispute has ever arisen in the corpus of legal precedent as to whether "goods" in s 59 was limited only to inventory or stock-in-trade.

[62] For this reason, we were fortified in our view that the fixed assets sold under the asset purchase agreement in the present case came within the meaning of "goods" within the meaning of s 21(1) of the Stamp Act 1949. Accordingly, the consideration paid for the fixed assets would not be dutiable on an ad valorem basis, by reason solely of s 21(1). Nonetheless, the asset purchase agreement constituted a "conveyance on sale" of the fixed assets, because - as explained at paras [28] and [29] ante - the property in the fixed assets passed to the respondent by the asset purchase agreement without the need for any further act to be taken by the parties to the agreement".

[62] We are of the considered view that the position in England, whilst persuasive, must be taken in light of their legislative evolution in respect of the meaning of the term 'goods'. The United Kingdom taxing authority has taken a more expansive reading of the word 'goods' and has not limited the exception in s 59 of their Act to mere inventory or stock in trade. The reason behind this stance may be traced to their legislative history and intent. This legislative evolution of the meaning of the term 'goods' was discussed in one of the leading English textbooks on stamp duty, The Law of Stamp Duties (Alpe), (25th Ed), as follows:

What are "goods, wares or merchandise".

"The phrase "goods, wares or merchandise" in exemption (3) also occurs (in connection with ad valorem duty) in s 59(1) (post, p 191) and in the Finance Act, s 36 (1) (post, p,510). Its meaning was extended by the Electric Lighting Act 1909, s 19, which provides as follows:

19. Electrical energy shall be deemed to be goods, wares or merchandise for the purpose of the Stamp Act, 1891 (which makes certain contracts chargeable with stamp duty as conveyances on sale), and also for the purposes of the exemption numbered 3 under the heading "Agreement or any Memorandum of an Agreement" contained in the First Schedule to that Act.

The phrase includes all corporeal moveable property (Benjamin on Sale, 8th Ed., p 172). It occurs in s 17 of the Statute of Frauds 1677. All contracts governed by that section as amended by Lord Tenterden's Act of 1828 (9 Geo. IV c.14) were within the corresponding exemption in former stamp Acts.

Section 17 of the Statute of Frauds, 1677, was replaced by the Sale of Goods Act 1893. Section 62(1) of that Act defines "goods" as follows:

62(1). In this Act, unless the context or subject matter otherwise requires...''Goods" includes all chattels personal other than things in action and money, and in Scotland all corporeal movables except money. The term includes emblements, industrial growing crops, and things attached to or forming part of the land which are agreed to be severed before sale or under the contract of sale."

[63] Hence, the term 'goods' in s 59 of the UK Act, had evolved and attained a meaning of its own by virtue of various statutory enactments. There was an express extension of its meaning by the UK Electric Lighting Act 1909. Further, the UK Sale of Goods Act 1893 (which replaced the Statute of Frauds 1677) had included personal chattels in the definition of 'goods'. This explains why the UK Tax Authority, and for that matter their courts, construed the term 'goods' in s 59 of their Act widely to include goods held as inventory or stock, as well as goods that were capital in nature. Thus came to be their practice of not limiting the 'goods' exception in s 59 of the UK Act merely to inventory or stock in trade, but expanding it to all goods.

[64] Hence, against this historical legislative background, it is not surprising that the English taxing authority adopted the practice that in contracts for sale of business, all goods regardless of whether used for trading or non- trading, were excluded, and not susceptible to ad valorem duty. However, the Malaysian Stamp Act does not have a similar legislative history or evolution as in England. Hence, the term 'goods' in s 21(1) of the Act must be construed within the framework of the Act applying the appropriate canons of statutory interpretation, particularly the interpretive canon of noscitur a sociis.

[65] The maxim noscitur a sociis, or the associated words rule, was explained by Abdoolcader J in Ipoh Garden Sdn Bhd v. Ismail Mahyuddin Enterprise Sdn Bhd [1975] 1 MLRH 517, in the following manner:

It is a fundamental rule in the construction of statutes that associated words (noscitur a sociis) explain and limit each other. The meaning of doubtful word or phrase in a statute may be ascertained by a consideration of the company in which it is found and the meaning of the words which are associated with it. The rule noscitur a sociis is frequently applied to ascertain the meaning of a word and consequently the intention of the legislature by reference to the context, and by considering whether the word in question and the surrounding words are, in fact, ejusdem generis, and referable to the same subject matter. Especially must it be remembered that the sense and meaning of the law can be collected only by comparing one part with another and by viewing all the parts together as one whole, and not one part only by itself.

[66] And more recently, this Court speaking through Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat CJ had occasion to explain and apply this rule of statutory construction in Maple Amalgamated Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Bank Pertanian Malaysia Berhad [2021] 5 MLRA 337, in the following terms:

[60] In our view, the words "transfer, convey or dispose of employed in s 214A ought to be construed having regard to the maxim of noscitur a sociis — the associated words rule. According to learned author Ruth Sullivan in Statutory Interpretation (2nd edn, Irwin Law Inc, 2007), at p 175, this cannon of construction operates thus:

When two or more words or phrases perform a parallel function within a provision and are linked by "and" or "or", the meaning of each is presumed to be influenced by the others. The interpreter looks for a pattern or a common theme in the words or phrases, which may be relied on to resolve ambiguity or to fix the scope of the provision.

[61] The author cites an example of the application of the maxim by reference to the judgment of Martin JA of the Court of Appeal of Ontario in R v. Goulis [1981] 33 OR (2d) 55 ("Goulis").

[62] The issue in Goulis was whether the accused, who was declared a bankrupt, was guilty of "concealing" items of his property in his statement of property to the trustee. The facts were such that he did not disclose the relevant information to the trustee. The question was whether the word "conceal" required a positive act of concealment or whether the failure to simply disclose sufficient information itself amounted to "concealment". Section 350 of the statute in question, provided as follows:

350. Everyone who:

(a) with intent to defraud his creditors,

(i) makes or causes to be made a gift, conveyance, assignment, sale, transfer or delivery of his property, or

(ii) removes, conceals or disposes of any of his property, or

(b) with intent that any one should defraud his creditors, receives any property by means of or in relation to which an offence has been committed under para (a), is guilty of an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for two years.

[63] Goulis was acquitted on the charge as the court of first instance found that the failure to disclose information did not amount to "concealment". On appeal, the decision was affirmed by the Court of Appeal. In particular, this is what Martin JA held:

It is an ancient rule of statutory construction (commonly expressed by the Latin maxim, noscitur a sociis) that the meaning of a doubtful word may be ascertained by reference to the meaning of words associated with it... When two or more words which are susceptible of analogous meanings are coupled together they are understood to be used in their cognate sense. They take their colour from each other, the meaning of the more general being restricted to a sense analogous to the less general...

[Emphasis Added]

In this case, the words which lend colour to the word "conceals" are, first, the word "removes", which clearly refers to a physical removal of property, and second, the words "disposes of ", which, standing in contrast to the kind of disposition which is expressly dealt with in subpara (i) of the same para (a), namely, one which is made by "gift, conveyance, assignment, sale, transfer or delivery", strongly suggests the kind of disposition which results from a positive act taken by a person to physically part with his property. In my view the association of "conceals" with the words "removes" or "disposes of in s 350(a)(ii) shows that the word "conceals" is there used by Parliament in a sense which contemplates a positive act of concealment.

[67] Similarly, in the present case, the meaning of the contentious word 'goods', in s 21(1) of the Act must be construed noscitur a sociis by reference to its two associated words, namely, 'wares' and 'merchandise', as they take contextual colour from each other.

[68] The rule is that, in the absence of a definition in the Act, ordinary everyday meaning must be given to any word the meaning of which is contentious, in doing so, resort may be had to the dictionary meaning. This was the approach taken by this Court in Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Majlis Daerah Segamat [2022] 2 MLRA 334, where it was held:

[70] Before we examine the meaning of these words in the well-known and authoritative dictionaries, perhaps it will be useful to note that statutory words and phrases are to be understood in their ordinary meaning; everyday meaning'" unless the context indicates that they bear a technical meaning. The rule is based on the presumption that legislature is most likely to have intended the language to be understood in their ordinary sense and on the value that people subject to such laws will more likely comprehend the rights and obligations granted to them. One of the ways to determine the meaning of a word is to turn to dictionaries as a source of information about the word usage.

See also the Court of Appeal's decision in Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri v. Classic Japan (M) Sdn Bhd [2022] 4 MLRA 219.

[69] The Oxford English Dictionary defines 'ware' as:

"Articles of merchandise or manufacture; the things which a merchant, tradesman or pedlar has to sell; goods; commodities".

[70] And the dictionary meaning of 'merchandise' as found in several dictionaries is as follows:

1. Black's Law Dictionary:

"1. In general, a movable object involved in trade or traffic; that which is passed from hand to hand by purchase and sale. 2. In particular, that which is dealt in by merchants; an article of trading or the class of objects in which trade is carried on by physical transfer; collectively, mercantile goods, wares or commodities, or any subjects of regular trade, animate as well as inanimate. This definition generally excludes real estate, ships, intangibles such as software, and the like, and does not apply to money, stocks, bonds, notes, or other mere representatives or measures of actual commodities or values. - Also termed (in senses 1 & 2) article of merchandise. 3. Purchase and sale; trade; traffic, dealing, or advantage from dealing."

2. The Oxford English Dictionary:

"The action or business of buying and selling commodities for profit; trading; the commodities of commerce; movables which may be bought and sold; A saleable commodity, an article of commerce"

[71] Now, as for the word 'goods', the following dictionary meanings are available for reference and assistance:

1. Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English:

1. Things that are produced to be sold. 2. Possessions that can be moved... 3. Things (not people) that are transported by rail or road.

2. Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary:

1. Items for sale, or the things that you own. 2. Items, but not people, which are transported by railway or road.

3. Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English:

1. Things that are produced in order to be sold. 2. Things that someone owns and that can be moved.... 3. Things which are carried by road, train etc....

4. Blacks' Law Dictionary:

1. Tangible or movable personal property other than money; esp., articles of trade or items of merchandise 2. Things that have value, whether tangible or not.

5. The Oxford English Dictionary:

Property: now moveable property; money; livestock; merchandise, ware (now chiefly manufactured articles).

[72] As can be seen from the above, the meaning of 'goods' in the various dictionaries is consistent with the meaning of 'wares' and 'merchandise'. The Oxford Advanced Learner, Cambridge and Longman all define 'goods' as things for sale or produced to be sold, whilst the Oxford English Dictionary likens it to wares and merchandise (which definition both covered an article of merchandise or manufacture or commerce). Further, Black's Law Dictionary specifically states that 'goods' is notably an article of trade and an item of merchandise, it must be emphasised that none of the dictionary meanings denote 'goods' as capital or non-trading movable properties.

[73] Hence, we agree with the Senior Revenue Counsel that the Court of Appeal fell into error when it said that the dictionary meaning of 'goods' in Black's Law Dictionary and Oxford English Dictionary as advanced by the respondent was of no assistance in the construction of that word as it appears in s 21(1) of the Act. The dictionary meaning of the words 'goods, ware and merchandise' clearly shows that they all refer to trading goods, and that is very useful in determining the meaning of the word 'goods' and the intent of the legislature in using this specific word in s 21(1) of the Act.

[74] Further, similar construction applies with regard to the exemption given to agreements for sale of goods, wares and merchandise under exemption (a) of Item 4 of the First Schedule. The meaning of 'goods' therein also applies to the sale of goods in the course of trading, and not otherwise as contended by learned counsel for the appellant.

[75] Learned counsel for the appellant further referred to the word 'stock' found immediately after the words 'goods, wares or merchandise' in s 21(1) of the Act and submitted that this was a specific reference to stock-in-trade or trading goods, and as such, argued that the word 'goods' cannot be construed to mean trading goods, but must instead be taken to mean non-trading movable properties. We are unable to accept this contention. The word 'stock' is defined in s 2 of the Act as follows:

"stock" includes any share in the capital stock or funded debt of any corporation, company or society in Malaysia or elsewhere and any share in the stocks or funds of the Government of Malaysia or of any other Government or country;

Thus, it is clear that the term 'stock' used in s 21(1) does not refer at all to trading goods. Instead, it refers to shares in the capital stock or funded debt of a corporation, company, or society in Malaysia or any shares in the stocks or funds of the Government of Malaysia or any other Government or country.

[76] Hence, we are of the considered view that only trading goods would come under the exception to the second category of properties in s 21(1), and non- trading moveable properties would be chargeable with ad valorem duty under s 21(1) of the Act read with Item 32(a) of the First Schedule. Thus, to that extent, we find the Court of Appeal to have erred and the decision of the Court of Appeal in that respect is reversed.

Issue (iii): Whether The Collector Of Stamp Duties May Raise A Stamp Duty Assessment Without Specifying Which Sub-Limb Of Item 32 Of The First Schedule Of The Act That The Collector Has Invoked

[77] The Federal Court in Pemungut Duti Setem lwn. Lee Koy Eng (Sebagai Pentadbir Bagi Harta Pusaka Tan Kok Lee @ Tan Chin Chai, Si Mati) [2022] MLRAU 312 laid down the principle that in determining a stamp duty appeal by way of Case Stated, the High Court is required solely to answer the question of law posed for the opinion of the High Court. Hence, the High Court had no other duty but to answer the question that had been put forth for the opinion of the High Court in the Case Stated. The issue regarding the non-specification of the sub-limb of Item 32 was not posed as a question for the determination of the High Court in the Case Stated. Thus, the appellant would be precluded from raising this issue.

[78] In any event, the appellant knew very well that the stamp duty assessment was made by the respondent under sub-item (a) of Item 32 which provides for imposition of ad valorem duty on sale of any property, except for stock, shares, marketable securities and accounts receivables or book debts mentioned in sub- item (c). The question put forth by the appellant in the Case Stated to the High Court clearly points to Item 32(a) of the First Schedule. Hence, there is no uncertainty as to which sub-item of Item 32 of the First Schedule would apply to the Agreement.

[79] The stamp duty payable on the Agreement was assessed on the basis of a conveyance on sale, ie as sale or transfer of business, whereupon the only applicable provision is s 21(1) of the Act read together with Item 32(a) of the First Schedule. There is no other possible provision under Item 32 relating to ad valorem duty that could apply to the instrument other than sub-Item (a). All the other sub-Items on ad valorem duty had no possible connection or relevance to the instrument. Thus, the Agreement was treated, as a conveyance on sale. This being the case, the Agreement clearly falls under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule.

[80] As the Agreement falls within the instrument specified with duty under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule, the Agreement cannot be regarded as an instrument liable to duty under Item 4 of the First Schedule.

Answers To The Questions Posed

[81] Therefore, our answers to the questions posed are as follows:

Question 1: Whether the Asset Purchase Agreement was a conveyance on sale within the meaning of s 21(1) of the Stamp Act 1949 which is dutiable under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Stamp Act 1949.

Answer: We answer in the affirmative. The Agreement was a conveyance on sale within the meaning of s 21(1) of the Act and is chargeable with duty under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Act.

Question 2: Whether the Asset Purchase Agreement falls under the exception under s 21(1) of the Stamp Act, and if the answer is in the affirmative, was the Court of Appeal correct to subject the said Agreement to ad valorem duty under Item 32 (a) of First Schedule of the Stamp Act 1949.

Answer: We answer in the negative. The Agreement does not fall under any of the exceptions in s 21(1) of the Act. The Agreement is chargeable with ad valorem duty as an instrument of conveyance on sale under Item 32(a) of the First Schedule of the Act.

Question 3: Whether the deeming provision in cl 2.3 (c)(i) of the Asset Purchase Agreement makes the said agreement an instrument (ie conveyance on sale) which falls under s 21(1) of the Stamp Act 1949.

Answer: We answer in the negative. The contractual deeming provision in cl 2.3(c)(i) of the Agreement is immaterial to the determination of whether the Agreement is a conveyance on sale under s 21(1) of the Act as the timing of the completion of the transaction is not a determinative factor.

Question 4: Whether the Collector of Stamp Duties may raise a stamp duty assessment without specifying which sub-limb of Item 32 of the First Schedule of the Stamp Act 1949 the Collector had invoked.

Answer: We decline to answer. This is a non-issue.

Conclusion

[82] In the premise of the foregoing, the appeal is dismissed with costs. The Order of the Court of Appeal is affirmed, albeit for the reasons stated above.