Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Hashim Hamzah CJM, Faizah Jamaludin, Meor Hashimi Abdul Hamid JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: K-01(NCvC)(W)-36-01-2024]

8 December 2025

Tort: Negligence — Duty of care — Appellant had suffered serious injuries, resulting in paralysis of the lower half of his body, when a coconut tree unexpectedly fell on him while he was on Pantai Chenang beach, Langkawi — Claim by appellant against respondent for negligence and breach of statutory duty — Whether respondent, as local authority, owed a duty under s 101 Local Government Act 1976 to control, supervise and maintain coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach, but failed in this responsibility — Whether appellant succeeded in proving his claim against respondent

This was the appellant's appeal against the decision of the High Court dismissing his claim against the respondent. The appellant had suffered serious injuries, resulting in paralysis of the lower half of his body, when a coconut tree unexpectedly fell on him while he was on Pantai Chenang beach, Langkawi, on 9 January 2019. This incident formed the basis of his claim against the respondent, the local authority for Langkawi established under the Local Government Act 1976 ("LGA 1976"). The appellant's claim against the respondent was based on allegations of negligence and breach of statutory duty under the LGA 1976. He contended that the respondent, as the local authority, owed a duty under s 101 of the LGA 1976 to control, supervise, and maintain the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach, but failed in this responsibility. In his action before the High Court, the appellant sought, among other reliefs, special damages amounting to RM4,594,577.42, general damages, aggravated and/or exemplary damages (to be assessed by the High Court) together with interest and costs. In the present appeal, the following issues required determination: (i) whether the Pantai Chenang beach formed part of the respondent's administrative area and jurisdiction; (ii) whether the respondent owed a statutory duty under s 101 of the LGA 1976; (iii) whether the respondent breached its statutory duty and/or duty of care; and (iv) whether liability might be inferred against the respondent under the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur.

Held (allowing the appellant's appeal):

(1) The respondent, being the local authority established in accordance with the LGA 1976, was mandated to administer the affairs of Langkawi pursuant to s 8 of the LGA 1976. This statutory mandate extended to all areas within the boundaries of the district of Langkawi, and it followed that the inclusion of Pantai Chenang beach within the defined jurisdiction meant the respondent was both authorised and obligated to oversee its administration. Consequently, any argument to the contrary, whether premised on the nature of "beach" under the LGA 1976 or on administrative correspondence, did not alter the operation of s 8 of the LGA 1976, which unequivocally conferred upon the respondent the duty to manage the entirety of Langkawi's local authority area. In light of this determination, the respondent's statutory duties under s 101 of the LGA 1976 must be interpreted to include the responsibilities associated with the management, supervision, and maintenance of Pantai Chenang beach and its environs. The local authority's remit encompassed not only the oversight of public parks and open spaces but also the obligation to address matters relating to trees that might affect public safety or convenience within its jurisdiction. (paras 21, 22 & 33)

(2) Based on the majority decision of the Federal Court in Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur and this Court's recent decision in Pengarah Jurutera Daerah Jabatan Kerja Raya Seremban & Ors v. Iqmal Izzuddeen Mohd Rosthy, it was established that the respondent had a statutory obligation under s 101(b) and (c) of the LGA 1976 to trim or remove trees, as well as to manage and supervise open spaces and holiday sites within Langkawi areas under its jurisdiction. Furthermore, pursuant to s 101(cc)(i), the respondent was required to remove coconut trees, even when such trees were located on private property. Accordingly, the respondent owed a duty of care to the appellant and to members of the public to remove any tree that posed a potential threat to public safety and to oversee the management and supervision of open spaces and holiday sites within Langkawi. This duty encompassed the trimming, maintenance, supervision, and control of trees and open spaces in the Pantai Chenang beach area, irrespective of whether the land was privately owned or State land. (paras 49-50)

(3) The law was settled that to prove breach of a statutory duty, it was enough to show that the defendant failed to perform a specific duty required by statute. In this case, by the respondent's own admission, it did not take any steps to supervise or maintain the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach. It also did not trim or remove any coconut trees that were dangerous to the public on the said beach, even though the beach area was within its administrative area. The respondent only supervised, maintained, trimmed, and removed trees that were on the main roads in Langkawi. Therefore, the respondent, due to its non-performance, had breached its statutory duties under the LGA 1976. Additionally, the respondent had breached its duty of care to the appellant under common law for failing to take reasonable care to supervise, maintain, trim and/or remove the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach. (paras 59-61)

(4) In light of the respondent's admitted failure to supervise, monitor and maintain the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach, coupled with its omission to trim or remove the coconut trees posing a danger to the public, the respondent's breach of statutory duty and duty of care were clearly established. Therefore, it was not necessary for the appellant to invoke res ipsa loquitur. Moreover, as the exact cause of the appellant's injury, a coconut tree falling on him, was known, the appellant could not rely on res ipsa loquitur. (para 65)

(5) Based on the analysis of the evidence presented during trial and the applicable law, the appellant had satisfactorily proven on a balance of probabilities that: (i) Pantai Chenang beach came within the administrative jurisdiction of the respondent; (ii) the respondent had statutory duties under s 101 of the LGA 1976 to supervise, maintain and control trees in the Pantai Chenang beach area and to trim or remove any tree that posed a potential threat to public safety, irrespective of whether the land was privately owned or State land; (iii) the respondent had breached its statutory duties and duty of care in not performing the said statutory duties in respect of the coconut trees in the Pantai Chenang beach area; and (iv) the appellant suffered injuries and damages as a result of the respondent's breach of its statutory duties and duty of care. Further, the defence of Act of God and the doctrine of volenti non fit injuria did not apply, and the appellant was not contributorily negligent for the injuries he suffered due to the respondent's breach of statutory duty and duty of care. Accordingly, the High Court was plainly wrong in dismissing the appellant's claim against the respondent. (paras 88-90)

Case(s) referred to:

Abdul Ghani Hamid v. Abdul Nasir Abdul Jabbar & Anor [1995] 2 MLRH 795 (refd)

Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur [2015] 1 MLRA 87 (folld)

Dalip Bhagwan Singh v. PP [1997] 1 MLRA 653 (refd)

Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 (refd)

Nor Azlina Abdul Aziz v. Expert Project Management Sdn Bhd [2017] 6 MLRA 561 (refd)

Pengarah Jurutera Daerah Jabatan Kerja Raya Seremban & Yang Lain lwn. Iqmal Izzuddeen Mohd Rosthy & Yang Lain & Satu Lagi Rayuan [2025] MLRAU 391 (folld)

Sabah Shell Petroleum Co Ltd & Anor v. The Owners Of And/Or Any Other Persons Interested In The Ship Or Vessel The Borcos Takdir [2012] 4 MLRH 560 (refd)

Scott v. London and St Katherine Docks [1865] 3 H & C 596 (refd)

Smith v. Cammell, Laird & Co Ltd [1940] AC 242 (refd)

Syaiful Amri Matimbang & Ors v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur & Anor [2024] 6 MLRH 322 (folld)

Teoh Guat Looi v. Ng Hong Guan [1998] 2 MLRA 47 (refd)

Young v. Bristol Aeroplane Co Ltd [1944] KB 718; [1944] 2 All ER 293 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Local Government Act 1976, ss 2, 3, 8, 101(b), (c), (cc)(i)

National Land Code, s 76

Counsel:

For the appellant: Tseng Seng Guan (Lily Chua & Nur Farah Farhana Effendy Onn with him); M/s Lily Chua & Associates

For the respondent: Ahmad Fadzli Abdul Salam (Muhammad Najwan Mohd Shukri with him); M/s Tawfeek Badjenid & Partners

[For the High Court judgment, please refer to Yong Shui Tian lwn. Majlis Perbandaraan Langkawi Bandaraya Pelancongan (Lamp 1, 12 & 16) [2025] MLRHU 287]

JUDGMENT

Faizah Jamaludin JCA:

A. Introduction

[1] This appeal arises from the decision of the High Court delivered on 11 December 2023, which dismissed the appellant's claim against the respondent with costs of RM10,000.00.

[2] The appellant suffered serious injuries, resulting in paralysis of the lower half of his body, when a coconut tree unexpectedly fell on him whilst he was on Pantai Chenang beach, Langkawi, on 9 January 2019. This incident forms the basis of his claim against the respondent.

[3] The respondent is the local authority for Langkawi, established under the Local Government Act 1976 ("LGA 1976").

• The Appellant's Claim

[4] The appellant's claim against the respondent is based on allegations of negligence and breach of statutory duty under the LGA 1976. He contends that the respondent, as the local authority, owed a duty under s 101 of the LGA 1976 to control, supervise, and maintain the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach, but failed in this responsibility. In his action before the High Court, the appellant sought, among other reliefs, special damages amounting to RM4,594,577.42, general damages, aggravated and/or exemplary damages (to be assessed by the High Court), together with interest and costs.

• The Respondent's Defence

[5] The respondent accepts that it is the local authority for Langkawi under the LGA 1976. Nevertheless, it firmly denies any allegations of negligence or breach of statutory duty, asserting that it cannot be held liable for the coconut tree falling on the appellant and the resulting injuries. The respondent's defence is four-fold:

(a) Jurisdiction Over Incident Location: The respondent contends that the site of the incident at Pantai Chenang beach, where the coconut tree fell, does not fall within its area of responsibility, control, or supervision. The respondent asserts that the coconut tree fell on private land; therefore, it does not bear any responsibility for the incident and the resulting injury to the appellant.

(b) Scope of Statutory Responsibility: The respondent argues that its obligations under the LGA 1976 are not absolute, and the said Act does not impose a strict or onerous duty upon local authorities, such that every incident would automatically amount to a breach of statutory duty.

(c) Act of God Defence and Volenti Non Fit Injuria: Alternatively, the respondent contends that the coconut tree fell due to strong winds, which qualifies as an Act of God and was therefore unavoidable. The respondent also claims that the principle of volenti non fit injuria applies because the appellant voluntarily and knowingly accepted the risk of the coconut tree falling, which led to his injuries. As such, the respondent maintains that it cannot be held responsible for incidents arising from such unforeseeable events.

(d) Proper Discharge of Duties: The respondent argues that even if the site of the incident was within its jurisdiction, it had diligently carried out its statutory obligations, including the proper maintenance of trees as required by law. Thus, it contends that the occurrence of the incident does not indicate any failure on its part in fulfilling its statutory duties.

• Findings Of The High Court

[6] After a full trial, the High Court concluded that the appellant had not established that the respondent, in its capacity as a local authority, owed a statutory duty or a duty of care to the appellant. The court further found that there was no breach of such duties by the respondent leading to the appellant's injuries, nor any negligence on the part of the respondent in maintaining the coconut trees or ensuring public safety at Pantai Chenang beach.

B. This Appeal

[7] Dissatisfied with the High Court's judgment, the appellant filed this appeal. The appellant contends that the High Court erred both in fact and in law in its findings and decision. Specifically, the appellant argues that the High Court incorrectly determined that the respondent did not bear statutory responsibilities for the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach, and erroneously concluded that the location of the incident was private land. This finding is said to contradict the Kedah Government Gazette dated 1 March 1979 (K.P.U. 11) ("Kedah Government Gazette"), which designates the entire District of Langkawi as falling under the respondent's local authority area.

[8] In his memorandum of appeal, the appellant sets out several grounds, asserting that the learned High Court Judge made the following errors in law and/or fact in arriving at his decision:

1) Failing to appreciate the purport of ss 101(b), (c) and (cc)(i) of the LGA 1976, which places statutory powers and responsibilities upon the respondent to: (a) prune or remove trees in the vicinity of the Pantai Chenang beach area; (b) maintain, supervise and control open spaces or recreational places in the vicinity of Pantai Chenang beach; (c) arrange, maintain and plant trees on land intended to be used as open spaces or recreational places; and/ or (d) require the owner or occupier of any premises to remove, reduce or prune, to the satisfaction of the local authority, any trees in the vicinity of Pantai Chenang beach that endanger public safety or comfort.

2) Failing to apply the correct principles regarding the statutory duties of the respondent as decided in Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur [2015] 1 MLRA 87, where it was held that "s 101 of the Act is worded in imperative terms, leaving no room for any discretion for the local authority in the exercise of its duty".

3) Failing to hold that the statutory duty and/or duty of care of the respondent as the local authority in the Pantai Chenang beach area extends to both private land and State land.

4) Failing to consider or failing to decide that the Kedah Government Gazette had declared the entire administrative district of Langkawi as the area of the respondent pursuant to s 3 of the LGA 1976.

5) Failing to hold that the respondent has responsibility, control and/or jurisdiction over Pantai Chenang beach, which forms part of the respondent's administrative area.

6) Failing to hold that there was a foreseeable risk of danger to the public when the respondent failed to inspect, supervise and/or maintain the trees at Pantai Chenang beach periodically.

7) Failing to hold that the negligence and/or failure of the respondent in carrying out their statutory duties caused the appellant to be struck by a coconut tree, resulting in disability.

8) Failing to hold that the principle of res ipsa loquitur applies to the appellant.

9) Failing to hold that the appellant is entitled to damages from the respondent.

C. Background Facts

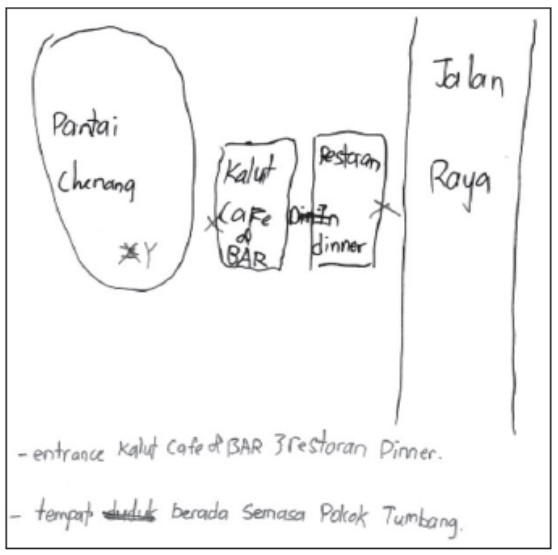

[9] The appellant was a tourist visiting Pantai Chenang beach, Langkawi, together with his family. On 9 January 2019, while walking along the beach in front of Mali-Mali Beach Resort, adjacent to Kalut Cafe & Bar on Pantai Chenang beach, a coconut tree unexpectedly toppled over, hitting him and two others. As a result of the incident, the appellant sustained paraplegia-paralysis of his lower body, while another victim tragically lost his life.

[10] The sketch plan below indicates the location of the appellant at the time when the coconut tree fell on him. His position is marked as "Y" on the plan. By referencing the appellant's location on the sketch plan, this Court is able to better appreciate the factual context in which the accident occurred. This is particularly relevant to the subsequent analysis of whether the respondent was subject to a statutory duty under s 101 of the LGA 1976 in respect of the maintenance, supervision, and control of trees and open spaces in the area. Furthermore, the sketch plan assists in determining whether the events in question took place within the respondent's administrative jurisdiction, as established by the Kedah Government Gazette.

D. Issues For Determination

[11] Based on the grounds of appeal presented by the appellant in his memorandum of appeal, and taking into account the facts in this case, we have framed the following issues for determination in this appeal.

(i) Whether the Pantai Chenang beach forms part of the respondent's administrative area and jurisdiction;

(ii) Whether the respondent owed a statutory duty under s 101 of the LGA 1976;

(iii) Whether the respondent breached its statutory duty and/or duty of care;

(iv) Whether liability may be inferred against the respondent under the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur.

[12] These issues are framed with reference to both the location of the incident illustrated in the sketch plan and the statutory responsibilities of the respondent under the LGA 1976. The analysis begins with an assessment of whether the respondent was obliged to maintain, supervise, and control trees and open spaces in Pantai Chenang beach, irrespective of whether the land is privately owned or State land.

[13] In addressing these issues for determination, it is necessary for this Court to examine the statutory framework governing the responsibilities of local authorities under the LGA 1976, evidence adduced during the trial, and the applicable legal principles, particularly in relation to the interpretation of ss 101(b), (c), and (cc)(i) of the LGA 1976 and the relevance of the Kedah Government Gazette, in light of the arguments presented by both parties and the legal authorities cited.

Issue (I): Whether The Pantai Chenang Beach Forms Part Of The Respondent's Administrative Area And Jurisdiction?

[14] The appellant contends that the High Court was wrong in holding that the respondent does not owe a statutory duty or a duty of care over the area where the coconut tree fell on him. He refers to ss 101(b), (c), and (cc)(i) of the LGA 1976, which empower the local authority to plant, trim, and remove trees that are endangering the public and supervise open spaces and holiday sites.

[15] The appellant contends that the Pantai Chenang beach comes within the jurisdiction of the respondent. This is because the whole administrative area of Langkawi was declared as under the respondent's jurisdiction with effect from 1 March 1979 in the Kedah Government Gazette. It argues that therefore, the respondent is responsible for maintaining, supervising, and controlling the trees on Pantai Chenang beach.

[16] The respondent, on the other hand, asserts that there is nothing in LGA 1976 which states or implies that the beach comes within the local authority area. It contends that the Pantai Chenang beach is a private area. It further argues that "beach" does not come within the definition of "public place" in s 2 of the LGA 1976. The respondent asserts in para 4.9 of its written submissions in reply, "... tanah Pantai bukanlah tanah awam di bawah kawalan Responden, sebaliknya ia merupakan tanah persendirian milik Kerajaan Negeri iaitu di bawah kawalan dan pentadbiran Pejabat Tanah dan Galian Langkawi". It contends that this is in line with the State Authority's power under s 76 of the National Land Code ("NLC") to alienate State land. The respondent further argues that a beach area falls outside the meaning of the word "road or street" in s 101 (cc)(i) of the LGA 1976.

• Our Analysis

[17] The LGA 1976 is an Act that was enacted to revise and consolidate the laws relating to local Government in Peninsular Malaysia. For the administration of local Government under the Act, the State Authority of each State in Peninsular Malaysia is empowered under s 3 of the Act by notification in the Government gazette to, inter alia, declare any area in the State to be a local authority area and define the boundaries of such local authority area. Section 3 of the LGA 1976 reads:

3. Declaration and determination of status of local authority area

For the administration of local Government under this Act, the State Authority, in consultation with the Minister and the Secretary of the Election Commission, may by notification in the Gazette:

(a) declare any area in such State to be a local authority area; (b) assign a name to such local authority area;

(c) define the boundaries of such local authority area; and

(d) determine the status of the local authority for such local authority area and such status shall be that of a Municipal Council or a District Council.

[18] In line with these statutory powers, the Kedah State Authority exercised its discretion to declare the entire administrative area of Langkawi as a local authorityarea,as evidenced intheKedahGovernmentGazette.This declaration assigned the status of District Council to the District Local Government Council Langkawi and established the boundaries for its jurisdiction, thereby conferring upon the respondent the administrative responsibility over the region, including locations such as Pantai Chenang beach. The Gazette notification serves as the legal instrument that defines the extent of the respondent's authority, ensuring that areas within the district, unless specifically excluded, fall under its remit for local administration and governance.

[19] The Kedah Government Gazette reads:

In exercise of the powers conferred by s 3 of the Local Government Act 1976, the State Authority in consultation with the Minister of Housing and Local Government and the Secretary of the Election Commission hereby declares that with effect from the 1st day of March 1979, the whole administrative area of the District of Langkawi to be a Local Authority area to be known as the District Local Government Council Langkawi and determines that the status of the local authority for such Local Authority area shall be that of a District Council.

[Emphasis Added]

[20] Therefore, based on s 3 of the LGA 1976 read together with the Kedah Government Gazette, the whole area of Langkawi, including Pantai Chenang beach, is a local authority area that comes within the jurisdiction of the respondent.

[21] Section 8 of the LGA 1976 provides that "the affairs of every local authority area shall be administered by a local authority established in accordance with this Act". In the context of the whole area of Langkawi, which has been declared a local authority area by the State Authority in the Kedah Government Gazette, the responsibility for administering its affairs is vested in the respondent. The respondent, being the local authority established in accordance with the LGA 1976, is mandated to administer the affairs of Langkawi in accordance with the Act, pursuant to s 8 of the LGA 1976.

[22] This statutory mandate extends to all areas within the boundaries of the district of Langkawi, and it follows that the inclusion of Pantai Chenang beach within the defined jurisdiction means the respondent is both authorised and obligated to oversee its administration. Consequently, any argument to the contrary - whether premised on the nature of "beach" under the Act or on administrative correspondence - does not alter the operation of s 8 of the LGA 1976, which unequivocally confers upon the respondent the duty to manage the entirety of Langkawi's local authority area.

[23] Learned counsel for the respondent argues that the Pantai Chenang beach does not come within its local authority area because "beach" does not come within the definition of "public place" in s 2 of the LGA 1976; the State Authority is empowered to alienate a beach under s 76 of the NLC; and "beach" falls outside the meaning of the word "road or street" in s 101(cc)(i) of the LGA 1976.

[24] For the reasons detailed in paras [25] - [32] below, we disagree with the respondent's claim that Pantai Chenang beach does not come within its local authority area.

• Does "Beach" Come Within The Definition Of "Public Place" In s 2 Of The LGA 1976?

[25]"Public place" is defined under s 2 of the LGA 1976 as "any open space, parking place, garden, recreation and pleasure ground or square, whether enclosed or not, set apart or appropriated for the use of the public or to which the public shall at any time have access". Beaches are open spaces, which the public has access at any time. Therefore, we find that "beach" falls squarely within the definition of "public place" under s 2 of the LGA 1976.

[26] Contrary to the respondent's argument, the authority granted to a State Authority under s 76 of the NLC to alienate beaches does not negate the classification of "beach" as a "public place" within the meaning of s 2 of the LGA 1976, nor does it affect the designation of Pantai Chenang beach as part of the respondent's local authority area according to s 3 of the LGA 1976 and the Kedah Government Gazette.

• Does The Respondent, As The Local Authority For Langkawi, Have Access To The Pantai Chenang Beach?

[27] The respondent claims that it does not have access to the Pantai Chenang beach area because its application to "supervise and control" ("untuk menyelia dan mengawal") the beach was rejected by the State Authority. However, upon review of the facts and documentation, we find that this contention is unfounded for the following reasons:

(a) The respondent's application, dated 8 October 2015, was not an application seeking custodianship or authority to supervise and control the Pantai Chenang beach, as claimed (see p 457 Rekod Rayuan Jilid 3A). Instead, the application was for custodial rights over the area of the sea extending 300 metres from the beach reserve along Pantai Chenang beach ("Permohonan hak jagaan kawasan laut 300 meter dari rezab pantai sepanjang Pantai Chenang"). This distinction is crucial, as it clarifies the scope and intent of the respondent's application and refutes its claim that it had sought access to the beach for supervisory and control purposes.

(b) The reply from the State Authority, dated 5 January 2017 (see p 459 Rekod Rayuan Jilid 3A), demonstrates that the application was not processed due to the respondent's failure to pay the requisite processing fee of RM500.00. This administrative issue, rather than any substantive rejection regarding the supervision of the beach, was the reason for the application not being considered; and

(c) Section 8 of the LGA 1976 imposes a statutory obligation on the respondent to administer and manage the affairs of the entire Langkawi area. This includes Pantai Chenang beach, which falls within the respondent's jurisdiction as established under the LGA 1976 and the Kedah Government Gazette. There is, therefore, no statutory requirement for the respondent to seek additional approval or apply to the State Authority for the right to supervise and control the Pantai Chenang beach area. The duty is inherent by virtue of the LGA 1976 and the respondent's status as the local authority for Langkawi.

• Does "Beach" Fall Outside The Meaning Of The Word "Road Or Street" In s 101(cc)(i) Of The LGA 1976?

[28] The word "road" is not defined in s 2 of the LGA 1976. However, the word "street" is defined in s 2 to include:

"any road, square, footway, passage or service road, whether a thoroughfare or not, over which the public have a right of way, and also the way over any bridge, and also includes any road, footway or passage, open court or open alley, used or intended to be used as a means of access to two or more holdings whether the public have a right of way over it or not, and all channels, drains and ditches at the side of any street shall be deemed to be part of such street".

[Emphasis Added]

[29] The High Court decision in Syaiful Amri Matimbang & Ors v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur & Anor [2024] 6 MLRH 322, at para 29, provides judicial interpretation regarding the meaning of "street" under the LGA 1976. The Court clarified that the term "street" encompasses "any road, square, footway, passage or service road, whether a thoroughfare or not, over which the public have a right of way." This interpretation extends the application of s 101 of the LGA 1976, when read together with s 2 of the Act, to situations where a tree is located wholly on private land, provided that the public has a right of way over that land.

[30] Applying this principle to the present case, it is evident that Pantai Chenang beach constitutes an area where the public has a right of way. As such, the beach falls within the statutory definition of "street" as provided under s 2 of the LGA 1976. Consequently, s 101(cc)(i), when read in conjunction with s 2 of the Act, is applicable to trees on the beach. This interpretation confirms that the responsibilities and powers vested in the respondent by these statutory provisions extend to trees located on beaches to which the public has access.

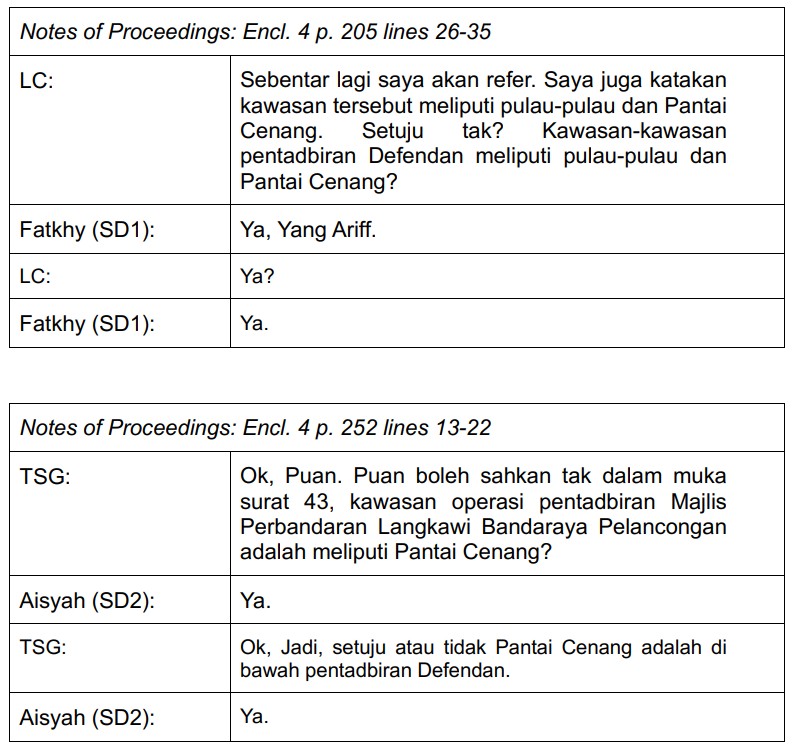

[31] Moreover, the respondent's own witnesses, Mohd Fatkhy bin Mohd Jamil ("SD1") and Siti Aisyah binti Mohd Taib ("SD2"), admitted during the trial that the Pantai Chenang beach area came within the respondent's administrative jurisdiction. Their testimonies are produced below:

Findings On Issue (I)

[32] Accordingly, for the reasons above, we find that Pantai Chenang beach forms part of the respondent's administrative area and jurisdiction of the LGA 1976.

[33] In light of this determination, the respondent's statutory duties under s 101 of the LGA 1976 must be interpreted to include the responsibilities associated with the management, supervision, and maintenance of Pantai Chenang beach and its environs. The local authority's remit encompasses not only the oversight of public parks and open spaces but also the obligation to address matters relating to trees that may affect public safety or convenience within its jurisdiction.

Issue (II): Whether The Respondent Owed A Statutory Duty Under s 101 Of The LGA 1976?

[34] Given the respondent's jurisdiction over the entire district of Langkawi, it is necessary to examine the statutory duties imposed on the local authority under the LGA 1976. Specifically, considering the legal framework and extent of the respondent's powers, whether there was an obligation - either a duty of care or a statutory one - to maintain and oversee coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach, especially considering its location and the respondent's arguments about its lack of duty under the LGA 1976.

• Provisions In s 101 Of The LGA 1976 In Relation To Trees

[35] Section 101 of the LGA 1976 details the responsibilities related to planting, maintaining, and removing trees. It also covers how open spaces and holiday sites within the respondent's jurisdiction should be managed and supervised.

[36] Pursuant to ss 101(b), (c), and (cc)(i) of the LGA 1976, the respondent is empowered to undertake a range of actions. This includes the authority to plant, trim, or remove trees as deemed appropriate. The respondent is also responsible for the construction, maintenance, supervision, and control of public parks, gardens, recreation grounds, open spaces, and holiday sites. Moreover, the legislation permits the local authority to require owners or occupiers of premises to remove, lower, or trim trees, shrubs, or hedges overhanging or interfering in any way with the traffic on any road or street or, in the opinion of the local authority, are likely to endanger public safety or convenience. In circumstances where a tree from private premises falls onto a public road or street, the local authority is empowered to remove the fallen tree and recover the expenses incurred from the owner or occupier.

[37] Accordingly, the scope of the respondent's statutory duties under the LGA 1976 encompasses not only the proactive management of public spaces and greenery but also the authority to require necessary action by private individuals to mitigate risks to public safety or traffic posed by trees, shrubs, or hedges within their premises.

[38] As outlined in para [5] above, the respondent advances two main arguments in its defence: First, the coconut tree in question was situated on private land. On this basis, the respondent asserts that it does not bear any responsibility for the maintenance or management of the tree. Secondly, the respondent maintains that its obligations under the LGA 1976 are not absolute. Specifically, it argues that the provisions of the LGA 1976 do not impose strict or onerous duties upon local authorities.

[39] Sections 101(b), (c) and (cc)(i) of the LGA 1976 states:

101. Further powers of local authority

In addition to any other powers conferred upon it by this Act or by any other written law a local authority shall have power to do all or any of the following things, namely-

...

(b) to plant, trim or remove trees;

(c) (i) to construct, maintain, supervise and control public parks, gardens, esplanades, recreation grounds, playing fields, children's playgrounds, open spaces, holiday sites, swimming pools, stadia, aquaria, gymnasia, community centres and refreshment rooms;

(ii) to lease, acquire, let, layout, plant, improve, equip and maintain lands for the purpose of being used as public parks, gardens, esplanades, recreation grounds, playing fields, children's playgrounds, open spaces, holiday sites, swimming pools, stadia, aquaria, gymnasia and community centres and to erect thereon any pavilion, recreation room or refreshment room or other buildings;

...

(cc) to r equire the owner or occupier of any premises to do any of the following acts-

(i)to remove, lower or trim to the satisfaction of the local authority any tree, shrub or hedge overhanging or interfering in any way with the traffic on any road or street or with any wires or works of the local authority or which in the opinion of the local authority is likely to endanger the public safety or convenience and in the event of any tree situated in private premises falling across any public road or street the local authority may remove the fallen tree and the expenses incurred shall be charged on and recoverable from the owner or occupier thereof;

[Emphasis Added]

[40] In Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur (supra), the Federal Court considered the following question of law:

"to what extent do the powers conferred under ss 101(b) and (cc) of the Local Government Act 1976 confer a duty of care on the local authority".

[41] In that case, the respondent was the local authority entrusted to administer the city of Kuala Lumpur under the LGA 1976. The appellant was driving his car along Jalan Duta, Kuala Lumpur, when a tree fell and crushed his car. As a result, the appellant suffered serious injuries and was paralysed from the neck down.

[42] The Federal Court, by a majority decision, found that s 101(cc)(i) of the LGA 1976 clearly imposes a statutory duty on the respondent local authority to remove any tree that is likely to cause danger to public safety. Raus Sharif PCA (as he then was), delivering the majority judgment of the Federal Court, held:

[17] There is no doubt that s 101(cc)(i) clearly imposes a statutory duty on the defendant to remove any tree that is likely to cause danger to public safety. The words in s 101(cc)(i) is clear and unambiguous. It has been drafted in such a manner so as to impose responsibility on the defendant. It imposes a duty on the defendant to act and ensure that public roads are kept safe from trees aligned to it.

...

[21]... the defendant's stance was that any mishap to the road users caused by the trees located on private land was not within their jurisdiction. With respect, I disagree. In my considered view it does not matter that the tree was on a private land, as under the Act the defendant can require the owner or occupier of any premises to remove or trim the tree. The Act also does not prohibit the defendant from entering any private land to cut or trim trees that pose a danger to the public. The defendant should have constantly supervised and trimmed all hazardous trees, immaterial of whether the trees stood on its land or otherwise. Section 101 of the Act clearly imposes a duty of care on the defendant, with the duty extending to the defendant to enter into private land to remove or lower or trim any tree, shrub or hedge before they cause any harm in light of the private land owner's neglect or failure to remove or trim the trees.

[22] Based on the aforesaid provision the obvious danger to road users brought about by the tree aligned to the highway along Jalan Duta would justify the defendant entering the private property to remedy the situation. Unfortunately, the defendant did not do so premised in the misconceived notion that it was not their business. I find that s 101 of the Act is worded in imperative terms, leaving no room for any discretion for the local authority in the exercise of its duty. The defendant was statutorily empowered to take the appropriate action when any breach is "likely to endanger the public safety" namely to trim the tree or to require the owner or occupier of any premises to remove, lower or trim any tree. The words so employed in s 101(cc)(i) of the Act ie, "likely to endanger" gives rise to the probability of the occurrence of such incident that triggers the safety standard required by the local authority to take action before harm is caused.

[23] S ection 101(cc)(i) is a statutory duty which imposes a responsibility on the defendant to act and ensure that public roads are kept safe from trees aligned to it. As an authority for this proposition I refer to the case of Ohrby v. Ryde Commissioners [1864] 5 B & S 743 cited by learned counsel for the plaintiff. The Ryde Commissioners in that case were responsible to place fences on the footways for the protection of foot passengers. The commissioners failed to carry out this duty. The plaintiff then slipped and fell off from the highway resulting in personal injuries. The court held that as a result of the powers given to the commissioners, they had a duty to ensure that the footways were safe and hence liable for any injuries caused by their failure...

In the case of Ohrby v. Ryde Commissioners (supra), much emphasis was placed by the court on the imperative words employed in the statute governing the duties of the commissioners to impose a common law duty on the public authority for the protection of the road users/public. Similarly in our case I am of the considered view that the words employed in s 101 is clear in that it imposes a duty of care on the part of the defendant to protect road users/ public.

[Emphasis Added]

[43] In Pengarah Jurutera Daerah Jabatan Kerja Raya Seremban & Yang Lain lwn. Iqmal Izzuddeen Mohd Rosthy & Yang Lain & Satu Lagi Rayuan [2025] MLRAU 391, this Court held that pursuant to s 101(b) of the LGA 1976, it was the duty of the local authority - Yang Dipertua Majlis Perbandaran Seremban and the Majlis Perbandaran Seremban - to ensure the proper supervision and maintenance of the tree in question. Despite the tree being situated on land belonging to JKR Seremban, this Court found that the local authority was wholly responsible for the accident and the injuries suffered by the plaintiff. We held that the responsibility arose from the local authority's failure to adequately supervise and maintain the tree, which ultimately led to its collapse on the day of the incident. This case illustrates the strict statutory obligations placed on local authorities to safeguard public safety by undertaking appropriate maintenance of trees within their jurisdiction, regardless of land ownership.

• Doctrine Of Stare Decisis

[44] Under the doctrine of stare decisis, courts are required to follow the decisions of higher courts within the same judicial hierarchy. Specifically, decisions of the Federal Court are binding on the Court of Appeal, the High Court, and all subordinate courts. Likewise, decisions of the Court of Appeal must be followed by the High Court and all courts below it in the hierarchy. This structure upholds the authority of higher courts and maintains uniformity in legal interpretation and application.

[45] As a general rule, the Court of Appeal is also bound by its own previous decisions. However, the seminal case of Young v. Bristol Aeroplane Co Ltd [1944] KB 718; [1944] 2 All ER 293 established important exceptions to this rule. The Court of Appeal may depart from its earlier rulings in three distinct situations:

• When there are conflicting decisions within the Court of Appeal itself;

• When a previous decision is inconsistent with a judgment of the Federal Court; or

• Where the earlier decision was made per incuriam, meaning through lack of due regard to the law or relevant authorities.

[46] This principle - that the Court of Appeal is generally bound by its own prior decisions, but with these three exceptions - has been affirmed by the Federal Court in Dalip Bhagwan Singh v. PP [1997] 1 MLRA 653.

[47] It is important to note that only the majority judgment of a higher court is binding upon lower courts. Although dissenting or minority judgments may offer persuasive reasoning, they do not have binding authority and cannot dictate the legal position that lower courts are obliged to follow.

[48] In this context, it is noteworthy that the respondent's counsel sought to advance the argument that the duties imposed upon local authorities under ss 101(b) and 101(cc) of the LGA 1976 are not absolute. In doing so, counsel relied upon the dissenting judgment of the Federal Court in Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur: referenced in para 5.3 of the respondent's written submissions in reply. However, counsel failed to disclose that the portion of the judgment cited was, in fact, from the minority or dissenting opinion of the Federal Court, not the majority judgment. As an officer of the Court, it is regrettable that counsel omitted to clarify this critical fact. Such omission risks misleading this Court regarding the binding nature of the authority relied upon.

Findings On Issue (II)

[49] Based on the majority decision of the Federal Court in Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur and this Court's recent decision in Pengarah Jurutera Daerah Jabatan Kerja Raya Seremban & Yang Lain lwn. Iqmal Izzuddeen Mohd Rosthy & Yang Lain & Satu Lagi Rayuan, it is established that the respondent has a statutory obligation under ss 101(b) and (c) of the LGA 1976 to trim or remove trees, as well as to manage and supervise open spaces and holiday sites within Langkawi areas under its jurisdiction. Furthermore, pursuant to s 101(cc)(i), the respondent is required to remove coconut trees, even when such trees are located on private property.

[50] Accordingly, we find that the respondent owes a duty of care to the appellant and to members of the public to remove any tree that poses a potential threat to public safety and to oversee the management and supervision of open spaces and holiday sites within Langkawi. This duty encompasses the trimming, maintenance, supervision, and control of trees and open spaces in the Pantai Chenang beach area, irrespective of whether the land is privately owned or State land.

Issue (III): Whether The Respondent Breached Its Statutory Duty And/Or Duty Of Care?

[51] It is a settled principle of law that breach of statutory duty occurs simply from non-performance of the said duty, regardless of the defendant's level of care. Accordingly, to establish breach of a statutory duty, it is not necessary to prove any absence of care on the part of the person upon whom the statutory duty is imposed. The mere non-performance of the statutory duty itself constitutes a breach.

[52] This approach contrasts with the requirements under common law for breach of duty of care. Under common law, a claimant must show that the defendant failed to exercise reasonable care to avoid causing a foreseeable harm.

[53] The High Court in the case of Abdul Ghani Hamid v. Abdul Nasir Abdul Jabbar & Anor [1995] 2 MLRH 795, addressed the requirements for establishing breach of statutory duty. The Court applied principles set out by the House of Lords in S mith v. Cammell, Laird & Co Ltd [1940] AC 242 that to prove breach of a statutory duty, it is sufficient to demonstrate that the defendant failed to perform a specific duty mandated by statute. Abdul Malik Ishak J (as he then was) articulated this distinction, emphasising that the statutory framework establishes its own threshold for liability, which is separate from the common law standard of negligence. He said:

On breach of statutory duty,... I can do no better than to quote the erudite words of Lord Atkin in Smith v. Cammell, Laird & Co Ltd [1940] AC 242 especially at p 258 where His Lordship had this to say:

"It is precisely in the absolute obligation imposed by statute to perform or forbear from performing a specified activity that a breach of statutory duty differs from the obligation imposed by common law, which is to take reasonable care to avoid injuring another."

...

... once it has been proved that a particular statutory duty has not been performed, it becomes actionable without having to prove any lack of care or diligence on the part of the person on whom the duty is imposed. In short, what matters is simply to show the non-performance of the act which the statute requires a person to perform, and that non- performances is in itself negligence on the part of that person.

[Emphasis Added]

[54] Accordingly, in determining whether the respondent breached its statutory duty under s 101 of the LGA 1976, the critical factor is whether the respondent had failed to perform a statutory duty imposed under the Act, rather than whether it had exercised reasonable care to prevent a foreseeable harm.

[55] Consequently, if it is established that the respondent did not perform the statutory act imposed on it by the Act - such as the removal or maintenance of hazardous trees or the supervision of open spaces - liability may arise solely by virtue of that non-performance. This statutory threshold for liability stands apart from the common law standard.

[56] The jurisprudence, thus, supports the proposition that the respondent's omission to act in accordance with the duties set out under s 101 of the LGA 1976 is sufficient to constitute a breach, irrespective of whether the respondent acted with diligence or care. This distinction is pivotal in assessing liability in this present case, where the respondent's statutory obligations were clear and any failure to discharge them, as required by law, is actionable without further evidence of negligence.

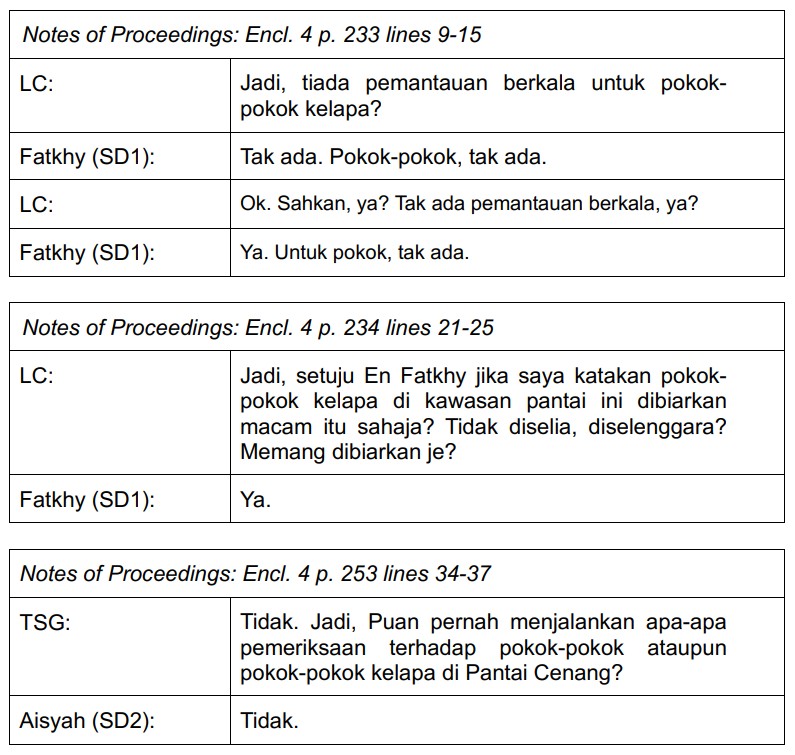

[57] During the course of the trial, both the respondent's witnesses - SD1 and SD2 - admitted that the respondent had not taken any action to monitor or maintain the coconut trees situated along Pantai Chenang beach. Their admissions were clear in confirming that no steps had been taken by the respondent with respect to the monitoring, upkeep or management of these trees. Their testimonies are produced below:

[58] SD2 reiterated during re-examination by the respondent's counsel that the respondent maintained the trees on the main roads only and not coconut trees on the beach. SD2's testimony is produced below:

Findings On Issue (III)

[59] The law is settled that to prove breach of a statutory duty, it is enough to show that the defendant failed to perform a specific duty required by statute. In this case, by the respondent's own admission, it did not take any steps to supervise or maintain the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach. It also did not trim or remove any coconut trees that were dangerous to the public on the said beach, even though the beach area was within its administrative area. As SD2 informed the Court, the respondent only supervised, maintained, trimmed, and removed trees that are on the main roads in Langkawi.

[60] Therefore, we find that the respondent - due to its non-performance - had breached its statutory duties under the LGA 1976.

[61] Additionally, we further find that the respondent had breached its duty of care to the appellant under common law for failing to take reasonable care to supervise, maintain, trim and/or remove the coconut trees on the Pantai Chenang beach. The Federal Court in its majority judgment in Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur, held that "the words employed in s 101 is clear in that it imposes a duty of care on the part of the defendant to protect road users/public".

Issue (IV): Whether Liability May Be Inferred Against The Respondent Under The Doctrine Of Res Ipsa Loquitur?

[62] One of the grounds of appeal raised by the appellant was that the learned High Court Judge did not consider its reliance on the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur to establish a prima facie case of negligence against the respondent for the coconut tree falling on and injuring the appellant.

[63] What is res ipsa loquitur? It is a rule of evidence that allows a court to infer negligence on the part of the defendant. It is not a principle of law. As stated in Clerk & Lindsell on Torts (20th Edn), res ipsa loquitur:

... It is only a convenient and label to apply to a set of circumstances in which a claimant proves a case so as to call for a rebuttal from the defendant, without having to allege and prove any specific act or omission on the part of the defendant. He merely proves a result, not any particular act or omission producing the result.

[64] To rely on res ipsa loquitur, the appellant must show: (i) the injury to him could not have happened without negligence; (ii) the injury was caused under the sole management and control of the respondent or someone for whom it is responsible or whom it has a right of control; and (iii) the exact cause of damage is not known: see Scott v. London and St Katherine Docks [1865] 3 H & C 596; Teoh Guat Looi v. Ng Hong Guan [1998] 2 MLRA 47; Sabah Shell Petroleum Co Ltd & Anor v. The Owners Of And/Or Any Other Persons Interested In The Ship Or Vessel The Borcos Takdir [2012] 4 MLRH 560.

Findings On Issue (IV)

[65] In light of the respondent's admitted failure to supervise, monitor, and maintain the coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach, coupled with its omission to trim or remove the coconut trees posing a danger to the public, the respondent's breach of statutory duty and duty of care are clearly established. Therefore, it is not necessary for the appellant to invoke res ipsa loquitur. Moreover, as the exact cause of the appellant's injury - a coconut tree falling on him - is known, the appellant cannot rely on res ipsa loquitur.

E. Is Appellate Intervention Warranted?

[66] The law on appellate intervention is settled. An appellate court must not interfere with the trial judge's conclusions on the primary facts unless it is satisfied that the trial judge was "plainly wrong". A "plainly wrong decision" is a decision arrived by the trial judge due to no or insufficient judicial appreciation of evidence and/or a material error of the law: see Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 ("Ng Hoo Kui").

[67] The necessity for appellate intervention in this case hinges on whether the learned High Court Judge's findings concerning the control, supervision, and maintenance of coconut trees on Pantai Chenang beach were adequately reasoned, founded upon the correct interpretation of the relevant law, and supported by sufficient judicial assessment of the evidence presented to the court.

[68] The learned High Court Judge made a finding of fact in para 22 of his grounds of judgment ("GOJ") that the appellant had failed to prove the area where the coconut tree fell on the appellant was under the control, supervision and maintenance of the respondent. In making the finding of fact, the learned judge made a general statement that "after examining and evaluating the evidence of the plaintiff's witness" he was satisfied that the appellant failed to prove on a balance of probabilities that the area where the coconut tree fell and hit the plaintiff and caused the injury to the plaintiff was under the control, supervision and maintenance of the defendant.

[69] His Lordship then went on to conclude in para 23 of the GOJ that because the appellant failed to prove that the area where the coconut tree fell and hit the appellant and caused the injury to the appellant was under control, supervision and maintenance of the respondent, "it may therefore be inferred that the area is owned by an individual, company, a firm or a business". Para 22 and 23 of the GOJ are produced below:

[22] Setelah Mahkamah ini meneliti dan menilai segala keterangan saksi- saksi Plaintif, Mahkamah ini berpuas hati dan mendapati bahawa Plaintif telah gagal membuktikan atas imbangan kebarangkalian yang kawasan di mana pokok kelapa di Pantai Chenang itu tumbang dan menimpa Plaintif dan menyebabkan kecederaan kepada Plaintif itu berada di bawah kawalan, seliaan dan selenggaraan Defendan. Sehubungan dengan itu, Mahkamah ini berpendapat, inter alia, bahawa-

(a) Plaintif telah gagal membuktikan bahawa sebagai Pihak Berkuasa Tempatan, Defendan mempunyai kewajipan statutori dan/atau kewajipan berhati-hati terhadap Plaintif;

(b) Plaintif telah gagal membuktikan bahawa Defendan telah mengingkari kewajipan statutori dan/atau kewajipan berhati-hati sehingga menyebabkan kecederaan separa lumpuh terhadap Plaintif; dan

(c) Plaintif telah gagal membuktikan bahawa Defendan telah melakukan kecuaian dalam menyelenggara pokok-pokok kelapa di kawasan Pantai Chenang dan memastikan keselamatan pelancong-pelancong, pengguna- pengguna dan orang awam.

[23] Memandangkan Plaintif telah gagal membuktikan bahawa kawasan di mana pokok kelapa di Pantai Chenang itu tumbang dan menimpa Plaintif di bawah kawalan, seliaan dan selenggaraan Defendan, maka boleh diandaikan bahawa kawasan itu dimiliki oleh orang perseorangan, syarikat atau perniagaan. Sekiranya fakta ini benar, maka pokok-pokok kelapa di kawasan ini sepatutnya berada di bawah kawalan, seliaan dan selenggaraan orang perseorangan, syarikat atau perniagaan tersebut.

[70] The paragraphs in the GOJ where the learned High Court Judge reached his findings of fact against the appellant are notably non-speaking. Specifically, the Judge did not analyse the precise location where the coconut tree fell. He did not refer to or discuss the sketch plan - which was the sole evidence on where the incident occurred. This omission is particularly significant given the absence of any reference to or engagement with the relevant statutory provisions, such as those within the LGA 1976 or the Kedah Government Gazette, which could have clarified whether the coconut tree fell within an area subject to the respondent's control, supervision, and maintenance.

[71] Furthermore, the learned Judge did not identify or discuss the appellant's evidence that he said to have "examined and evaluated" prior to concluding that the area in question was not under the control, supervision, and maintenance of the respondent. Additionally, the judgment did not clarify the rationale for the Judge's decision to confine his analysis to the appellant's evidence, without consideration of the respondent's evidence in reaching his conclusion. In our view, if the learned Judge had considered the provisions in the LGA 1976 and the Kedah Government Gazette, and the admissions made by SD1 and SD2 that Pantai Chenang beach was within the respondent's administrative area, he would have likely reached a different finding of fact.

[72] This lack of engagement with critical evidence and statutory materials, coupled with the failure to address the respondent's admissions as to the administrative boundaries, calls into question the adequacy of the learned Judge's factual analysis. In the circumstances, the minimal reasoning provided, together with the omission of a thorough evaluation of both parties' evidence and the relevant regulatory framework, raises legitimate concerns as to whether the decision can be said to be one which a reasonable judge would have reached. This, in turn, underscores the necessity for appellate scrutiny of the trial court's findings, particularly where such findings were reached without sufficient judicial appreciation of the entirety of the evidence and the applicable law.

[73] The learned High Court Judge erred in concluding that Pantai Chenang beach constituted private land and, as a result, that the respondent's obligations regarding the supervision and maintenance of trees in Langkawi did not extend to trees situated on private property.

[74] This conclusion stands in direct contradiction of the provisions of the LGA 1976 and to the legal position set out by the Federal Court's majority decision in Ahmad Jaafar Abdul Latiff v. Dato' Bandar Kuala Lumpur (supra). Specifically, the Federal Court clarified that the statutory duties imposed on local authorities under s 101 of the LGA 1976 are not limited solely to public land. Rather, local authorities are required to address dangerous trees regardless of whether they are located on public, private, or State land.

[75] By restricting the respondent's duties in this manner, the High Court Judge overlooked the legal effect of the Federal Court's interpretation of s 101 of the LGA 1976, and consequently, reached a conclusion that is inconsistent with the applicable law. The High Court's reasoning fails to reflect the binding precedent which holds that the responsibility of local authorities to supervise and maintain trees of public concern is not confined by the ownership status of the land on which those trees stand.

[76] Furthermore, in para 26 of the GOJ, the learned Judge expressed the view that imposing comprehensive responsibility on the respondent for the maintenance, control, and supervision of all coconut trees and coconuts throughout Langkawi was both "unreasonable and illogical". The Judge reasoned that it would not be sensible to expect the respondent to ensure that no coconut tree falls and injures tourists or members of the public, especially when such trees and coconuts are located on privately owned land. This position was advanced in the judgment as a justification for limiting the scope of the respondent's statutory and/or common law duties, particularly in circumstances where ownership and control of the land in question rested with private individuals, companies, or businesses. Para 26 of the GOJ is produced below:

[26] Mengenai perkara ini Mahkamah ini berpendapat bahawa adalah tidak munasabah dan tidak masuk akal untuk meletakkan segala tanggungjawab kepada Defendan untuk menjaga, mengawal dan memantau semua pokok kelapa dan buah kelapa di seluruh Bandaraya Langkawi bagi memastikan pokok-pokok itu tidak tumbang dan menimpa pelancong-pelancong, pengguna-pengguna dan orang awam, apatah lagi jika pokok-pokok dan buah- buah kelapa itu milik orang perseorangan, syarikat, firma atau perniagaan dan terletak dalam kawasan milik oleh orang perseorangan, syarikat, firma atau perniagaan.

[Emphasis Added]

[77] It is a fundamental principle of law that the primary role of courts is to interpret and apply the provisions of statutes and legislation as enacted by Parliament or by the State legislature. Courts are not empowered to question the reasonableness or the logic of such legislation; their mandate is limited to the interpretation and application of the law as it stands.

[78] Moreover, the doctrine of stare decisis requires courts to follow precedents established by superior courts. The High Court, therefore, is obliged to adopt and adhere to the statutory and legislative interpretations provided by the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court. Any failure by the High Court to follow binding precedent constitutes a significant deviation from established legal principles and serves to undermine the authority of higher courts in relation to the interpretation and application of statutory duties imposed upon local authorities.

[79] Additionally, the lack of proper evaluation of the evidence adduced during the trial is apparent from the conclusion reached by the learned Judge that the coconut tree fell down because of strong winds on the night of 9 January 2019. The respondent claims that there were strong winds on the said night and the strong winds were an Act of God. It argues that the principle of volenti non fit injuria applies; hence, the appellant was negligent by strolling on Pantai Chenang beach despite the strong winds.

[80] The learned Judge accepted the respondent's claim. In para 29 of the GOJ, the learned Judge determined that the injury suffered by the appellant was the result of his own negligence. In arriving at this conclusion, His Lordship made a specific finding of fact that the winds were blowing strongly on the night of the incident. Based on this finding, the Judge reasoned that, as a reasonable person, the appellant ought not to have positioned himself beneath the coconut tree at that time, since doing so exposed him to the risk of injury and danger.

[81] This finding of fact by the learned Judge is completely at odds with the Jabatan Meteorologi Malaysia's ("JBM") record of the meteorological data in exhs "P2" and "P3" as well as the factual evidence by SP1 and SP2. Both the documentary and oral evidence showed the opposite - that the weather conditions on the night of the incident were normal without rain and with weak/light winds. Exhibit "P2" (at p 272 Rekod Rayuan Jilid 3A) is JBM's record "Hourly Surface Wind" for Pulau Langkawi on 9 January 2019. The document exhibited at pp 274-275 Rekod Rayuan Jilid 3A is JBM's "Observer's Handbox Wind Beaufort Scale: Specifications and Equivalent Speeds" ("Wind Beaufort Scale"). And exhibit "P3" (at p 273 Rekod Rayuan Jilid 3A) is a certified copy of JBM's record of "Hourly Rainfall Duration and Amount" for Pulau Langkawi on 9 January 2019. It shows that total rainfall (midnight to midnight) on 9 January 2019 was 0.0mm.

[82] Nor Sherizan Binti Darus ("SP1"), a meteorological officer who is the Ketua Penolong Pengarah in Pusat Iklim Nasional Malaysia, JBM, testified that exh "P2" shows that the wind speed at Pulau Langkawi at 11.00pm on 9 January 2019 was 3 meters per se cond ("m/s"). SP1 explained the Wind Beaufort Scale is the scale used to measure wind speed; and that a wind speed of 3 m/s is weak/mild.

[83] The appellant ("SP2") testified that at the time the coconut tree fell on him (at 11.00pm on 9 January 2019) there was no rain and there was only a little wind. SP2's testimony is supported by the documentary evidence - JBM's official records in "P2" and "P3" - and SP1's oral testimony, that on the night of 9 January 2019, the weather conditions were normal with no rain and weak/ light winds.

[84] The learned Judge, contrary to the documentary evidence in "P2" and "P3" and the testimonies of SP1 and SP2, found that on the night of the incident, the wind was blowing strongly, and went on to conclude that the appellant's injuries were caused by the appellant's negligence and not the respondent's. Para 29 of the GOJ is produced below:

[29] Dalam kes ini, memandangkan pada malam kejadian tersebut angin bertiup kencang, maka sebagai seorang yang munasabah (reasonable man), Plaintif tidak sepatutnya berada di bawah pokok kelapa pada masa itu kerana ia boleh mendedahkan Plaintif kepada perkara-perkara yang boleh mencederakan, mengancam dan/atau membahayakan keselamatan diri dan nyawa Plaintif. Oleh itu, pada pendapat Mahkamah ini, kecederaan yang menimpa Plaintif tersebut adalah berpunca daripada kecuaian Plaintif sendiri dan bukannya Defendan.

[Emphasis Added]

[85] The finding of fact made in para 29 of the GOJ - that there were strong winds in Langkawi during the night of the incident-shows that the learned Judge did not consider, did not properly evaluate or had an insufficient appreciation of the documentary and oral evidence adduced in court during the trial. All the evidence pointed to the fact that the wind was weak/mild at the time of the incident. Inexplicably, the learned Judge found that the wind was blowing strongly at the time of the incident.

[86] Harmindar Singh Dhaliwal JCA (as he was then known) clearly set out the circumstances that warrant appellate intervention in Nor Azlina Abdul Aziz v. Expert Project Management Sdn Bhd [2017] 6 MLRA 561. These circumstances are:

[20] Nevertheless there are occasions when appellate interference is warranted and these occasions have been well set out in numerous cases. Some of these occasions are:

(a) where the trial judge took into account irrelevant considerations and failed to give due weight to relevant considerations (see Director Of Forestry Sabah & Anor v. Mau Kam Tong & Ors And Another Appeal [2009] 3 MLRA 617);

(b) where there was no proper evaluation of the evidence by the trial judge (see Lee Nyan Hon & Brothers Sdn Bhd v. Metro Charm Sdn Bhd [2009] 2 MLRA 593);

(c) where the decision arrived at by the trial court was without judicial appreciation of the evidence (see Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1);

(d) where a trial court has so fundamentally misdirected itself, that no reasonable court which had properly directed itself and asked the correct questions, would have arrived at the same conclusion (see Raja Lob Sharuddin Raja Ahmad Terzali & Ors v. Sri Seltra Sdn Bhd [2007] 3 MLRA 224);

(e) where the trial judge was plainly wrong in arriving at his decision see Lee Ing Chin & Ors v. Gan Yook Chin & Anor [2003] 1 MLRA 95);

(f) where a trial judge had so manifestly failed to derive proper benefit from the undoubted advantage of seeing and hearing witnesses at the trial, and in reaching his conclusion, has not properly analysed the entirety of the evidence which was given before him (see First Count Sdn Bhd v. Wang Yew Logging & Plantation Sdn Bhd [2013] 4 MLRA 457, which followed the Privy Council case of Choo Kok Beng v. Choo Kok Hoe & Ors [1984] 1 MLRA 706); and

(g) where the judgment is based upon a wrong premise of fact or of law (see Perembun (M) Sdn Bhd v. Conlay Construction Sdn Bhd [2012] 2 MLRA 71).

[Emphasis Added]

[87] Accordingly, in view of the judge's limited analysis and absence of or inadequate evaluation of the evidence, and his misdirection of the law and the statutory framework - including binding authorities of the Federal Court on local authorities' statutory duties under s 101 of the LGA 1976, we find that appellate intervention is warranted under the "plainly wrong" test.

F. Conclusion

[88] Based on our analysis of the evidence presented during trial and the applicable law, we find that the appellant had satisfactorily proven on a balance of probabilities that: (i) Pantai Chenang beach comes within the administrative jurisdiction of the respondent; (ii) the respondent has statutory duties under s 101 of the LGA 1976 to supervise, maintain and control trees in the Pantai Chenang beach area and to trim or remove any tree that poses a potential threat to public safety, irrespective of whether the land is privately owned or State land; (iii) the respondent had breached its statutory duties and duty of care in not performing the said statutory duties in respect of the coconut trees in the Pantai Chenang beach area; and (iv) the appellant suffered injuries and damages as a result of the respondent's breach of its statutory duties and duty of care.

[89] Further, we conclude that the defence of Act of God and the doctrine of volenti non fit injuria do not apply, and the appellant was not contributorily negligent for the injuries he suffered due to the respondent's breach of statutory duty and duty of care.

[90] Accordingly, we find that the High Court was plainly wrong in dismissing the appellant's claim against the respondent.

G. Decision

[91] Therefore, for all the reasons above, we give judgment as regards liability as follows:

(a) The appellant's appeal is allowed; and

(b) The respondent is wholly liable for the injuries sustained by the appellant as a result of the coconut tree falling on him at Pantai Chenang beach, Langkawi on 9 January 2019.

[92] The High Court's judgment dated 11 December 2023 is set aside.

[93] As the High Court did not adjudicate and decide on the appellant's claim for damages, we remit the appellant's claim for damages for hearing before a different Judge at the High Court of Alor Setar.

[94] Costs in the sum of RM30,000.00 here and below, subject to allocatur.