High Court Sabah & Sarawak, Kota Kinabalu

Celestina Stuel Galid J

[Judicial Review Application No: BKI-25-14-6-2022]

7 November 2025

Administrative Law: Judicial review — Certiorari and mandamus — Rules of Court 2012, O 53 — Application in respect of Order "The Federal Constitution [Review of Special Grant Under Art 112D] [State of Sabah] Order 2022" ("Second Review Order") published by Federal Government — Whether Second Review Order failed to comply with art 112C of Federal Constitution, read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of Tenth Schedule and cls (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D — Whether decision in relation to Second Review Order illegal, irrational, procedurally improper and/or disproportionate

Constitutional Law: East Malaysian States — State of Sabah — Application for judicial review in respect of Order "The Federal Constitution [Review of Special Grant Under Art 112D] [State of Sabah] Order 2022" ("Second Review Order") published by Federal Government — Whether Second Review Order failed to comply with art 112C of Federal Constitution, read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of Tenth Schedule and cls (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D — Whether decision in relation to Second Review Order illegal, irrational, procedurally improper and/or disproportionate

Constitutional Law: Government — Federal Government — Application for judicial review in respect of Order "The Federal Constitution [Review of Special Grant Under art 112D] [State of Sabah] Order 2022" ("Second Review Order'") published by Federal Government — Whether Second Review Order failed to comply with art 112C of Federal Constitution, read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of Tenth Schedule and cls (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D — Whether decision in relation to Second Review Order illegal, irrational, procedurally improper and/or disproportionate

This was an application for Judicial Review ("JR") filed by the Sabah Law Society ("SLS") under O 53 of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC 2012"). SLS was an entity established under the Sabah Advocates Ordinance (Sabah Cap 2), while the 1st respondent was the Federal Government and the 2nd respondent the State Government of Sabah. By a Federal Government Gazette publication PU(A) 119/2022 dated 20 April 2022, the Federal Government published an Order, ie "The Federal Constitution [Review of Special Grant Under Art 112D] [State of Sabah] Order 2022" ("Second Review Order") which stated the following: "Special grant — for a period of five years with effect from 1 January 2022, the Government of the Federation shall make to the State of Sabah, in respect of the financial year 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025 and 2026, grants in the sum of RM125.6 million, RM129.7 million, RM133.8 million, RM138.1 million and RM142.6 million respectively; Revocation - the Sabah Special Grant (First Review) Order 1970 ("First Review Order") is revoked." In addition (and after the filing of this JR application), a Federal Government Gazette publication PU(A) 364/2023 dated 24 December 2023 was issued, publishing the Order "Federal Constitution [Review of Special Grant Under Art 112D] [State of Sabah] Order 2023" ("Third Review Order"). It was in respect of the Second Review Order that SLS applied for orders of certiorari and mandamus in the JR herein. SLS contended that the Second Review Order failed to comply with art 112C of the Federal Constitution ("FC"), read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule and cls (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D. Article 112C and subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the FC provided for the special annual grant by the Federation of Malaysia to the State of Sabah in respect of each financial year, commonly referred to as the State of Sabah's 40% Entitlement.

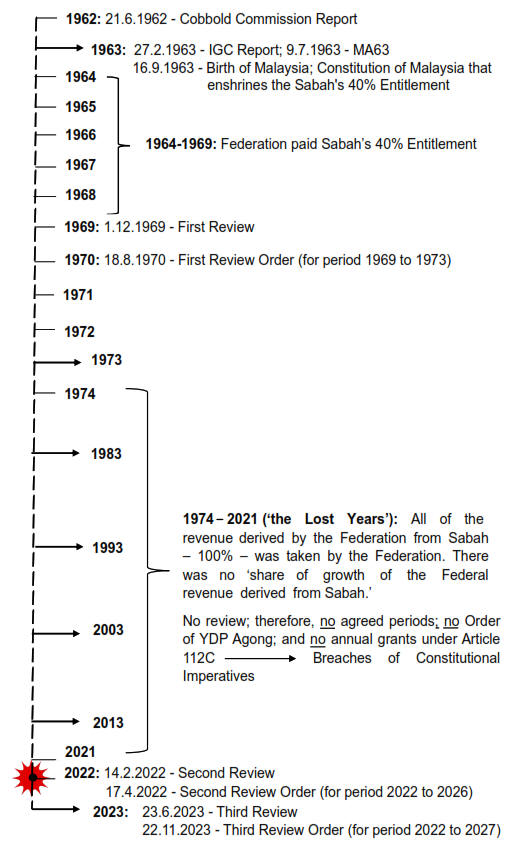

SLS' stance was that the Second Review Order was contrary to the imperatives of cls (1) and (4) of art 112D which mandated the Federal Government and the State Government (taking each clause in turn): (i) to conduct a review of the 40% Entitlement (provided under cl (1)(a) of art 112C) and any substituted or additional grant made by virtue of cl (1) of art 112D; (ii) for such review to make provision of a period of five years or (except in the case of the first review) such longer period as agreed between the Federation and the State of Sabah; and (iii) for the period covered by the second review to begin with the year 1974. It was contended that contrary to arts 112C and 112D, there was no review held in 1974 which resulted in the State of Sabah not making its 40% Entitlement in respect of each and all of the 48 years from 1974 to 2021 ("Lost Years"). It was further asserted that: (i) the Second Review Order was therefore ultra vires the express provisions of the FC and more particularly arts 112C and 112D read together with the Tenth Schedule, Parts III, IV and V thereto; (ii) there was a breach of natural justice as the 1st respondent had failed and/ or neglected to hold a Second Review for the period beginning in 1974. This had resulted in the 40% Entitlement of the State of Sabah under the FC to be ignored or discarded for 48 years in breach of the express provisions of the FC; (iii) the Second Review Order was contrary to the express provision of art 112C and art 112D of the FC as it failed to provide for each consecutive year for the period from 1974 to 2021 therein; (iv) the Second Review Order was irrational and unreasonable as it failed to take into account para 24(6), (8) and (9) of the Inter-Governmental Committee Report ("IGC Report") which entitled the State of Sabah to receive grants based on the 40% formula as provided under art 112C and Part IV of the Tenth Schedule for the period from 1974 to 2021; and (v) the Second Review Order was disproportionate to art 112C and 112D of the FC, particularly the application of the formula as set out in Part V of the Tenth Schedule thereto as the amount that would be derived from the 40% formula would be highly disproportionate to the amount purportedly agreed upon in the Second Review Order.

Held (allowing the application):

(1) The 1st respondent contended that there had been an on-going negotiation between the 1st respondent and the 2nd respondent since 1974. However, there was no evidence at all produced before this Court to support the 1st respondent's assertion on the existence of an on-going review. Not a single document was exhibited, only certain averments by the 1st respondent. One would think that after the lapse of some 48 years, some semblance of evidence would be forthcoming of such on-going review — the people of Sabah (whose interests had been and were directly affected) had a legitimate expectation and indeed deserved to know what exactly their Governments (Federal and State) had done in all those 48 years to realise and ensure the continuity of the conditions and safeguards that their forefathers had insisted on when they agreed to become part of the Federation of Malaysia. It was thus rather troubling, to say the least, that after some 48 years and this application being brought up for the first time, all the 1st respondent could rely on to support its claim as to the 48-year-long on-going review were only affidavit averments. If the argument was that the supporting documents were classified documents or "rahsia", it certainly did not stop the 1st respondent's counterpart, the 2nd respondent, from disclosing such similar documents. Even then, none of the documents produced by the 2nd respondent suggested that the review process started in 1974 and continued until 2021. Thus, the review therein could not have, by any stretch of imagination, covered the period during the Lost Years. As rightly pointed out by SLS, even if one were to entertain the idea of a 48-year-long and on-going review, such claim would be untenable when considered in the light of the clear constitutional provisions. (paras 155, 156, 157, 159, 160, 164 & 165)

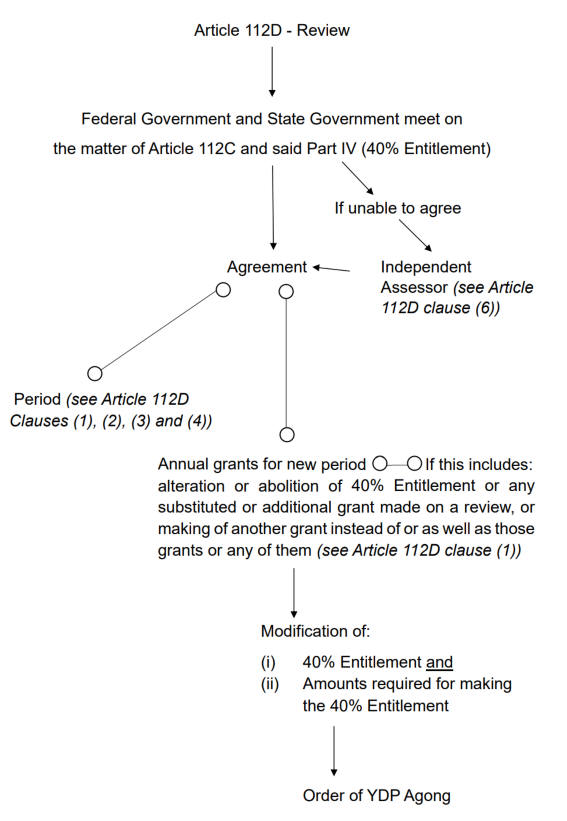

(2) A review as contemplated under art 112D of the FC must include the following elements: (i) meeting between the representatives of the Federal Government and the Sabah Government for the purpose of a review of the special grant; (ii) agreement between them as to a mandated fixed period of 5 years or another agreed period for the annual grant to be made (cls (1), (2), (3) and (4)); (iii) (a) agreement on the specified grant for each year in that mandated or agreed period, and (b) if agreement on the specified grants each year included alteration or abolition of the 40% Entitlement or any substituted or additional grant made on a review, or making of another grant instead of for as well as these grants or any of them for that agreed period; and (iv) then modification of the duty to make the 40% Entitlement and the amounts required for making the 40% Entitlement by an order of the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong. If in the process of carrying out the review under art 112D, the two Governments were unable to reach an agreement on any matter, it would be referred to an independent assessor, and his recommendations would be binding on the two Governments as if they were the agreement of those Governments as provided under cl (6) of art 112D. Taking the 1st respondent's case at the most, the only essential element under art 112D which would have been fulfilled by the purported ongoing review would have been that the two Governments had corresponded and/or met to broach the subject of a review of the special grant in 1974 and that this continued up until 2021. This amounted to procedural impropriety, was irrational and unreasonable. To accept the 1st respondent's argument on this issue would be to re-write art 112D so that the provision only required the Federal and State Governments to meet or correspond with each other on this matter. Taking it further, if accepted, the 1st respondent's interpretation would mean that the grant in 1973 might continue to apply indefinitely and even, ad infinitum. Likewise, it would allow the two Governments to embark on a never-ending on-going review. (paras 167-170)

(3) The 1st respondent's assertion that there was an on-going review from 1974 to 2021 and that the First Review Order remained in force until it was revoked by the Second Review Order. Counsel for SLS was quite correct to note that the 1st respondent's stance, if accepted, would result in an interpretation of art 112D, which would allow the outcome of a review conducted on 1 December 1969 between the two Governments to govern the amounts in grants made from the Federation to Sabah as many as 52 years later in 2021. The 1st respondent's stance that there was an on-going review from 1974 to 2021 and that the First Review Order remained in force until the Second Review Order in 2022 was not only irrational and unreasonable but absurd as it failed to consider cl (2) of art 112D, which provided that any review under the Article would consider the following: (i) the financial position of the 1st respondent; (ii) the needs of Sabah; and (iii) whether or not the revenue of Sabah was adequate to meet the cost of the State services. (paras 171-174)

(4) The 1st respondent's further contention that SLS ought to be precluded from contending that the Second Review Order was irrational and amounted to Wednesbury Unreasonableness on the ground that it was not pleaded in the Statement filed pursuant to O 53 of the ROC 2012 was not convincing. First, it was not a new or unpleaded ground. On the contrary, they were relevant considerations when construing art 112D and determining the lawfulness or otherwise of the Second Review Order. For the Second Review Order to be a properly conducted and rational review under art 112D, it must encompass at the very least when the last review was done, the period for which the review would cover, the financial position of the Federal Government and the needs of the State Government in regard to the State services with room for expansion, the amount of net revenue derived by the Federation from Sabah for each consecutive year in the period for which the review to agree to and make the special grant would cover, the amount of net revenue derived for the year 1963 to be readily available during the review. Clause (2) of art 112D expressly required this. The Second Review Order, in its omission of any consideration of the special grant, its annual amount, and allocation of payment for that period from 1974 to 2021, was irrational and unreasonable (Wednesbury sense). The words 'at the time of the review' appearing in cl (2) of art 112D could not be ignored, so that it could be accepted that the framers of the FC could or would have intended for a review that was outdated, by decades, to continue to govern the grants paid by the Federal Government to the State of Sabah. At the very least, common sense would dictate that the needs of Sabah in 2020, for instance, would not have been the same as it was in 1974. To put it another way, the sum of RM26.7 million under the First Review Order would have gone a long way towards the development of Sabah in 1974, but the same could not be said in the year 2020. However, that was what Sabah received then. (paras 175-179)

(5) It was argued for the 1st respondent that the absence of a review order in 1974 did not mean that "the Applicant" would by default be granted the 40% Entitlement as stipulated under art 112C(1)(a) read with s 2(1) of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the FC. The 1st respondent relied on art 112D(3) to support their justification for the yearly payment of RM26.7 million under the First Review Order from 1974 to 2021. However, the Senior Federal Counsel ("SFC") might have missed the point that the 40% Entitlement was to be granted to the State of Sabah and not "the Applicant" or SLS. Further, careful consideration of SLS' arguments showed that the "by default" arguments by SFC were too simplistic and failed to appreciate SLS' case which could be broken down as follows: (i) the FC in cl (1)(a) of art 112C mandated for the making of the 40% Entitlement from Federation to State; (ii) the only way to modify this provision was as set out in cl (1) of art 112D, by an order of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong; (iii) where there was no modification to the 40% Entitlement, there was no requirement for such an order of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong.; and (iv) but the converse was also true — where there was no order, no modification to the 40% Entitlement could be given effect to. The only way that a modification of the 40% Entitlement could be given effect to was by an order of the Yang di- Pertuan Agong. Any purported change to the 40% Entitlement, without such an order, was constitutionally impermissible. While it was true that the First Review Order did modify the 40% Entitlement mandated by cl (1)(a) of art 112C of the FC, it did not have the effect of modifying Sabah's constitutional rights beyond 1973. The First Review Order, which was an order of the Yang di- Pertuan Agong, was a subsidiary legislation and must yield to the primacy of the FC. To read it otherwise would be ultra vires to the FC. A plain reading of the First Review Order would show that there was nothing therein that remotely suggested that its effects went beyond 1973. It only expressly modified the 40% Entitlement in respect of the years 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972 and 1973. While the Second Review Order purported to revoke the First Review Order, there was nothing in it which allowed for the modification of the First Review Order so that it extended beyond 1973. In fact, nothing was stated about those Lost Years at all. (paras 187-194)

(6) The 1st respondent also contended that the First Review Order remained in force pursuant to cl (3) of art 112D during the Lost Years and until revoked by the Second Review Order. The 1st respondent's stand was that this provision excused the absence of any review or order in 1974 and justified the nonpayment of the 40% Entitlement to the State of Sabah in respect of the Lost Years. However, the taking away of the State of Sabah's constitutional rights to receive the 40% Entitlement in those Lost Years could not, by any means, be left to inferences or implications when the Second Review Order did not purport to make any (further) modification to the 40% Entitlement. That would have been a clear breach of natural justice and ultra vires the express provisions of the FC, in particular arts 112C and 112D read together with the Tenth Schedule, Parts III, IV and V thereto. If it were the case and such right had been superseded by the grant of the Second Review Order as contended by the 1st respondent, it must be expressly stated to be so. The converse would be true — the rights of the State of Sabah since 1974 to 2021 were never constitutionally modified or more importantly, lost. The interpretation by SLS which was preferable was that cl (3) was a temporary savings clause to avoid a constitutional vacuum during the period between the expiry of one review order and the implementation of the next. It preserved legality during the transitional period between two orders. It did not envisage or authorise prolonged non-compliance. Neither did it serve as a mechanism to justify indefinite inaction by the Federal Government or to displace its constitutional duty to conduct periodic reviews and, specifically, a review in 1974. To construe the provision the way the 1st respondent asserted would be to countenance its own breach by the executive. Clause (3) also prevented the Federation from being in breach of its duty to make the 40% Entitlement once the period of the existing order modifying that 40% Entitlement (as the First Review Order did) came to an end, but before the succeeding order came into effect to supersede it. This modification of the 40% Entitlement by the existing order only continued in force (and prevented the Federation from being in breach of its duty to make the 40% Entitlement) up till the point that the Second Review Order — which gave effect to a second review that should have been properly conducted pursuant to art 112D — took effect. (paras 195-200)

(7) On the facts herein, once the First Review Order was revoked by the Second Review Order, which gave effect to the second review, the modification was also thereafter revoked. At that point, the Federation's duty to make the 40% Entitlement to the State of Sabah immediately came into effect for the period of the Lost Years. This event, occurring not in 1974 as was mandated by the FC, but 48 years later, a fortiori triggered the Federation's duty to make the 40% Entitlement to the State of Sabah and which the two Governments were mandated to consider in their second review. Here, the two Governments, in breach of their constitutional duties imposed upon and powers vested in them under the FC at art 112C read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule and cls (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D, did not consider the 40% Entitlement in respect of the Lost Years. In circumstances where no review took place in 1974, and no review had ever taken place in respect of the period covered by the 48 Lost Years from 1974 to 2021, the 40% Entitlement remained due and payable by the Federation to the State of Sabah for each of those Lost Years. In breach of natural justice and legitimate expectation of the State of Sabah and her people, the Second Review Order made on 17 April 2022 and with effect from 1 January 2022 failed to provide for the making of annual grants for the period of the Lost Years (1974 to 2021). The Federation's duty to make the 40% Entitlement remained, and remained to be fulfilled, with the lifting of the First Review Order by the Second Review Order on 20 April 2022 (or 1 January 2022). (paras 202-205)

(8) Given the findings above, the Federal Government and the Sabah Government's use of their respective powers under art 112D of the FC not only amounted to an abuse of power but a breach of constitutional duties stipulated in that article and art 112C read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule. Hence, the decision in relation to the Second Review Order was illegal, irrational, procedurally improper and/or disproportionate. (paras 211-212)

(9) As for the reliefs sought, SLS had prayed for the remedy of certiorari to quash that part of the Second Review Order that was implicitly unlawful for the omission to consider the Lost Years to be read together with the remedy of declarations at prayers (2)(a) and (b) of its JR application. SLS had rightly submitted that the 40% Entitlement would have been a large part of the financial provision that, being revenue derived by the Federation from Sabah, should have been made and paid to the State of Sabah for the development of the public services, including the costs of state services. The State of Sabah, although indubitably rich in natural minerals — oil and gas, and palm oil — remained appallingly poor. This Court was entitled to consider that a person's right to his or her life and livelihood would include the right to the bare necessities of life. This was entrenched in cl (1) of art 5 of the FC, which provided that 'No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty save in accordance with law'. In the circumstances, these declarations were necessary in order for the two Governments to carry out the review of the special grant for the Lost Years that had been omitted in both the Second Review Order and the Third Review Order. (paras 213, 223, 224 & 225)

(10) SLS had also prayed for an order of mandamus in sub-paragraph 3(a) to carry out the mandatory review for the period since 1974. This was to remedy the omission and failure of the two Governments to review the 40% Entitlement for the Lost Years despite being under a duty and invested with power under the said constitutional provisions of the FC to carry out the mandatory review. The SFC argued that the relief of mandamus was not available to SLS, contending that SLS had failed to establish that the 1st respondent had a legal or statutory duty as a matter of course to provide a grant based on the 40% formula. This submission could not stand given this Court's findings on the failure by the two Governments to review the 40% Entitlement for the Lost Years. The order of mandamus was necessary to compel the two Governments to hold and conduct the review properly in accordance with the provisions of art 112D and art 112C read with s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the FC. This Court was within its powers to grant such a relief. The relief in sub-paragraph (3)(b) for the consequential payment order was also necessary following the earlier orders. Likewise, the additional remedy of an account would be appropriate to ensure that the efforts and fruits to the Sabah public were not to be frustrated. The earlier orders would not be sufficient and/or would be futile if the two Governments, who were entrusted by the FC to review the 40% Entitlement in respect of the Lost Years, were not made to account for the review and the results. (paras 226-229)

Case(s) referred to:

Advance Synergy Capital Sdn Bhd v. The Minister Of Finance Malaysia & Anor [2011] 1 MLRA 477 (distd)

Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd. v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] 1 KB 223 (refd)

Attorney General Of Malaysia v. Sabah Law Society; State Government Of Sabah (Intervener) [2024] 5 MLRA 565 (refd)

Attorney General Of Malaysia v. Sabah Law Society [2025] 1 MLRA 17 (refd)

Basheshar Nath v. Commissioner Of Income Tax, Delhi And Rajasthan [1959] AIR (SC) 149 (refd)

Behram Khurshid Pesikaka v. The State Of Bombay [1955] 1 SCR 613 (refd)

Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad v. Mohd Afrizan Husain [2022] 4 MLRA 547 (refd)

Civil Service Unions & Ors v. Minister Of Civil Service [1985] AC 374 (refd)

Datuk Hj Mohammad TufailMahmud & Ors v. Dato' Ting Check Sii [2009] 1 MLRA 602 (refd)

Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [2020] 2 MLRA 1 (refd)

Dhinesh Tanaphll v. Lembaga Pencegahan Jenayah & Ors [2022] 4 MLRA 452 (refd)

Dominic Lau Hoe Chai v. Maszlee Malik & Ors [2019] MLRHU 1449 (distd)

Dr Koay Cheng Boon v. Majlis Perubatan Malaysia [2012] 2 MLRA 23 (distd)

Dr Michael Jeyakumar Devaraj v. Peguam Negara Malaysia [2013] 2 MLRA 179 (refd)

Gujarat State Co-operative Land Development Ltd v. PR Mankad & Anor [1979] AIR 1203 (refd)

Indira Gandhi Mutho v. Pengarah Jabatan Agama Islam Perak & Ors And Other Appeals [2018] 2 MLRA 1 (folld)

JRI Resources Sdn Bhd v. Kuwait Finance House (Malaysia) Berhad; President Of Association Of Islamic Banking Institutions Malaysia & Anor (Interveners) [2019] 3 MLRA 87 (distd)

Keruntum Sdn Bhd v. The Director Of Forest & Ors [2018] 2 SSLR 167; [2018] 5 MLRA 175 (distd)

Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri v. Alcatel-Lucent Malaysia Sdn Bhd & Anor [2017] 1 MLRA 251 (refd)

Khaw Poh Chhuan v. Ng Gaik Peng & Yap Wan Chuan & Ors [1996] 1 MLRA 101 (refd)

Letitia Bosman v. PP & Other Appeals [2020] 5 MLRA 636 (distd)

Majlis Agama Islam Selangor v. Bong Boon Chuen & Ors [2009] 2 MLRA 453 (distd)

Mahisha Sulaiha Abdul Majeed v. Ketua Pengarah Pendaftaran & Ors And Another Appeal [2022] 6 MLRA 59 (folld)

Maria Chin Abdullah v. Ketua Pengarah Imigresen & Anor [2021] 3 MLRA 1 (distd)

Matadeen v. Pointu [1998] UKPC 9 (refd)

Minister Of Finance Government Of Sabah v. Petrojasa Sdn Bhd [2008] 1 MLRA 705 (refd)

Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai & Anor v. Muziadi Mukhtar [2019] 6 MLRA 307 (refd)

R Rama Chandran v. Industrial Court Of Malaysia & Anor [1996] 1 MELR 71; [1996] 1 MLRA 725 (refd)

Sabah Law Society v. The Government Of The Federation Of Malaysia & Anor [2023] MLRHU 2395 (refd)

Tan Sri Eric Chia Eng Hock v. PP [2006] 2 MLRA 556 (refd)

Tan Tek Seng v. Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan & Anor [1996] 1 MLRA 186 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Bandar Nusajaya Development Sdn Bhd [2016] 6 MLRA 103 (refd)

The Government Of The State Of Kelantan v. The Government Of The Federation Of Malaya And Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj [1963] 1 MLRH 160 (refd)

Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop Of Kuala Lumpur v. Menteri Dalam Negeri & Ors [2014] 4 MLRA 205 (refd)

TR Sandah Ak Tabau & Ors v. Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor And Other Appeals [2019] 5 MLRA 667 (distd)

Legislation referred to:

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, ss 74, 96(a), Schedule, para 1

Federal Constitution, arts 5(1), 12, 13, 71, 74, 76, 76A, 77, 96, 97, 110(1), 112C(1)(a), 112D(1), (2), (3), (4), (6), 128(1)(b), 160, Eighth Schedule, Ninth Schedule, Tenth Schedule, Part III, Part IV, s 2(1), Part V, ss 3, 4, Part VII

Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967, s 3

Rules of Court 2012, O 53 rr 3, 8(1)

Sales Tax Enactment 1998, s 6

Land Ordinance (Sabah) (Cap 68), ss 9, 31, 132

Other(s) referred to:

Jalihah Md Shah, Rosazman Hussin & Asmady Idris, Poverty Eradication Project in Sabah, Malaysia: New Initiative, New Challenges?, Planning Malaysia: Journal of the Malaysian Institute of Planners [2023], Vol 21, Issue 6, pp 477 — 492

Mazlianie Mohd Lan & Emeritus Professor Datuk Dr Shad Saleem Faruqi, Special Financial Provisions for Sabah under the Federal Constitution: The Issue of the 40% Special Grant, [2023] 50(2) JMCL 1

Tun Mohamed Suffian Hashim, An Introduction to the Constitution of Malaysia, 2nd Edn, Government Printer [1976], p 188, para 24 of the IGC Report

Counsel:

For the applicant: David Fung (Janice Junie Lim with him); M/s Alex Pang & Co;

Jeyan Marimuttu; M/s J Marimuttu & Partners

For the 1st respondent: Ahmad Hanir Hambaly @ Arwi (Atirah Aiman Rahim & Mohammad Solehheen Mohammad Zaki with him); AG's Chambers

JUDGMENT

Celestina Stuel Galid J:

Introduction

[1] On 17 October 2025, this court granted the application for judicial review filed by Sabah Law Society ("SLS") under O 53 of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC 2012").

[2] This judgment contains this court's reasoning in coming to its decision and is divided into the following sub-topics:

(i) The proceedings at the leave stage;

(ii) Salient background facts;

(iii) What is the 40% Entitlement?;

(iv) The remedies and orders prayed for by SLS;

(v) The respective parties' cases in a nutshell;

(vi) Preliminary issues;

(vii) This Court's decision on the merits (of the application); and

(viii) Conclusion and orders.

The Proceedings At The Leave Stage

[3] SLS' leave application (to commence the judicial review) was opposed by the Federal Attorney-General with the 2nd Respondent being allowed to intervene. Leave was granted by Ismail Brahim J (later JCA) on 11 November 2022 — see Sabah Law Society v. The Government Of The Federation Of Malaysia & Anor [2023] MLRHU 2395.

[4] The grant of leave was appealed against by the 1st Respondent to the Court of Appeal — see Attorney General Of Malaysia v. Sabah Law Society; State Government Of Sabah (Intervener) [2024] 5 MLRA 565. The appeal was dismissed on 18 June 2024.

[5] The 1st Respondent's leave application to appeal to the Federal Court against the Court of Appeal's decision was dismissed on 17 October 2024 — see Attorney General Of Malaysia v. Sabah Law Society [2025] 1 MLRA 17.

Salient Background Facts

[6] SLS is an entity established under Sabah Advocates Ordinance (Sabah Cap 2). Although its standing to bring the present judicial review was challenged by the 1st Respondent, this issue has been put to rest by the Federal Court which held that SLS has threshold locus standi to do so — see Attorney General of Malaysia v. Sabah Law Society.

[7] The 1st Respondent is the Federal Government while the 2nd Respondent is the State Government of Sabah. They will be interchangeably referred to herein as the 1st Respondent/the Federal Government and the 2nd Respondent/the State Government.

[8] By a Federal Government Gazette publication PU(A) 119/2022 dated 20 April 2022, the Federal Government published the Order "The Federal Constitution [Review of Special Grant Under art 112D] [State of Sabah] Order 2022 ("the Second Review Order")" which states the following:

"Special grant

2. For a period of five years with effect from 1 January 2022, the Government of the Federation shall make to the State of Sabah, in respect of the financial year 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025 and 2026, grants in the sum of RM125.6 million, RM129.7 million, RM133.8 million, RM138.1 million and RM142.6 million respectively.

Revocation

3. The Sabah Special Grant (First Review) Order 1970 [PU(A) 328/1970] is revoked."

[9] It was in respect of the Second Review Order that this judicial review was applied for. SLS contended that the Second Review Order failed to comply with art 112C of the Federal Constitution ("FC"), read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule and Clauses (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D.

[10] As a matter of additional background, Sabah Special Grant (First Review) Order 1970 ("the First Review Order") under art 112D was made on 18 August 1970. By the First Review Order, the Federal Government and Sabah Government agreed that instead of the grant specified in sub-section (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule to the FC, another grant be made for the period of five years as follows:

(i) 1969 — RM20 million

(ii) 1970 — RM21.5 million

(iii) 1971 — RM23.1 million

(iv) 1972 — RM24.8 million

(v) 1973 — RM26.7 million

[11] The period for the grant was from 1 January 1969 to 1 January 1974. Thereafter, the next review order would be the Second Review Order in 2022.

[12] In addition (and after the filing of this judicial review application), a Federal Government Gazette publication PU(A) 364/2023 dated 24 December 2023 was issued publishing the Order "Federal Constitution [Review of Special Grant Under art 112D] [State of Sabah] Order 2023" ("the Third Review Order") which states the following:

"Special grant

2.(1) For a period of six years with effect from 1 January 2022, the Government of the Federation shall make to the Government of the State of Sabah, in respect of the financial year 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, 2026 and 2027, grants in the amount of RM125.6 million, RM300 million, RM306 million, RM312 million, RM318 million and RM325 million respectively.

(2) The Government of Federation has made to the State of Sabah, in respect of the financial year 2022, grant in the amount of RM125.6 million on 16 June 2022.

Revocation

3. The Federal Constitution (Review of Special Grant under art 112D) (State of Sabah) Order 2022 [PU(A) 119/2022] is revoked."

What Is The 40% Entitlement?

[13] As the issues in this judicial review revolve on it, it would be helpful to have a brief explanation of what the State of Sabah's 40% Entitlement is.

[14] Article 112C and subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the FC provide for the special annual grant by the Federation of Malaysia to the State of Sabah in respect of each financial year. This special grant is commonly referred to as the State of Sabah's 40% Entitlement.

[15] This 40% Entitlement is to be contrasted from the other grants provided in Part VII of the FC which sets out the financial provisions and the financial management of the Federation applicable to all States. This includes the following:

(i) Development Grant — the Federation is required to pay into a fund known as the State Reserve Fund ("SRF") in respect of every financial year as may be determined to be necessary and may make grants out of the SRF for the purpose of development or generally to supplement its revenues.

(ii) State Taxes, fees and other revenue — the FC allocates certain taxes and revenues to be collected by the States. Article 110(1) of the FC provides that the States shall receive all proceeds from taxes, fees and other sources of revenue specified in Part III of the Tenth Schedule as far as collected, levied or raised within the State.

[16] Exhs "CST-4" to "CST-9" show that over and above the grants provided in Part VII of the FC, the State of Sabah received the 40% Entitlement from 1964 to 1968, then described as "Share of growth of Federal Revenue Derived from Sabah" in the following sums:

(i) 1964 — RM4,965,167.00

(ii) 1965 — RM8,199,340.00

(iii) 1966 — RM13,271,238.00

(iv) 1967 — RM22,178,172.00

(v) 1968 — RM21,097,923.00

[17] Illustrative of the matters stated in paragraphs 15 and 16 above, during the same period from 1964 to 1968, the State of Sabah is also shown to have received the following Capitation Grants and State Road Grants (apart from the 40% Entitlement):

The Remedies And Orders Prayed For

[18] SLS sought for the following remedies and orders in this application (verbatim):

"(1) An order of certiorari to remove into the High Court for the purpose of quashing such part of the decision contained in Gazette publication PU(A) 119/2022 dated 20 April 2022 and Gazette publication PU(A) 364/2023 dated 24 December 2023 as is or is implied to decide and publish that the duty of the 1st Respondent is otherwise than is as declared under paras 2 (a) and 2 (b) herein.

(2) A declaration that:

(a) The failure of the 1st Respondent to hold the second review in the year 1974 with the 2nd Respondent is a breach and contravention of its constitutional duty stipulated under art 112D, Clauses (1), (3) and (4) of the Federal Constitution.

(b) The 40% Entitlement under art 112C read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the Federal Constitution means an annual grant of two-fifths of the amount by which the net revenue derived by the Federation from the State of Sabah exceeds the net revenue which would have been derived in the year 1963 wherein net revenue is the revenue which accrues to the Federation less the amounts received by the State of Sabah in respect of assignments of that revenue under ss 3 or 4 of Part V of the Tenth Schedule of the Federal Constitution as depicted by the formula as shown:

Federal Revenue derived from Sabah in current Year [A]

Revenue Assigned to State [ss 3 or 4 of Part V of Tenth Schedule] [B]

Net Revenue derived from Sabah in current Year (A — B = C) [C]

Federal Revenue derived from Sabah in 1963 [D]

Revenue assigned to Sabah in 1963 [E]

Net Revenue derived from Sabah in 1963 (D — E = F) [F]

Special Grant due to Sabah in Current Year: 40% x (C — F = G) [G]

(c) The 40% Entitlement remains due and payable by the Federation to the State of Sabah for each consecutive financial year for the period from the year 1974 to the year 2021.

(d) A failure to pay the 40% Entitlement by the Federation to the State of Sabah for each consecutive financial year for the period from the year 1974 to the year 2021 is a breach of the fundamental right to property of the State of Sabah and ultimately of the fundamental right to life of the people of Sabah as enshrined under the respective art 13 and 5 of the Federal Constitution.

(3) And for the following orders:

(a) An order of mandamus directed to the 1st Respondent to hold another review with the 2nd Respondent under the provisions of art 112D of the Federal Constitution to give effect to the Federation making the 40% Entitlement to the State of Sabah under art 112C read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the Federal Constitution for each consecutive financial year for the period from the year 1974 to the year 2021 within 30 days and to reach an agreement within 90 days from the date of this order.

(b) An order that the 1st Respondent pays the entitlement as determined under para 3 (a) above to the 2nd Respondent or as constitutional damages for breach of art 5 and 13 of the Federal Constitution or both.

(c) An order that the 1st and 2nd Respondents account for the entitlement pursuant to the review undertaken under sub-para (3)(a) above."

The Respective Parties' Cases In A Nutshell

The Case For SLS

[19] SLS' stance was that the Second Review Order was contrary to the imperatives of Clauses (1) and (4) of art 112D which mandate the Federal Government and the State Government (taking each clause in turn):

(i) to conduct a review of the 40% Entitlement (provided under cl 1(a) of art 112C) and any substituted or additional grant made by virtue of cl (1) of art 112D;

(ii) for such review to make provision of a period of five years or (except in the case of the first review) such longer period as agreed between the Federation and the State of Sabah; and

(iii) for the period covered by the second review to begin with the year 1974.

[20] It was contended that contrary to arts 112C and 112D, there was no review held in 1974 which resulted in the State of Sabah not making its 40% Entitlement in respect of each and all of the 48 years from 1974 to 2021 ("the Lost Years").

[21] It was further asserted that:

(i) the Second Review Order was therefore ultra vires the express provisions of the FC and more particularly arts 112C and 112D read together with the Tenth Schedule Parts III, IV and V thereto;

(ii) there was a breach of natural justice as the 1st Respondent had failed and or neglected to hold a Second Review for the period beginning in 1974. This has resulted in the 40% Entitlement of the State of Sabah under the FC to be ignored or discarded for 48 years in breach of the express provisions of the FC;

(iii) the Second Review Order was contrary to the express provision of art 112C and art 112D of the FC as it failed to provide for each consecutive year for period from 1974 to 2021 therein;

(iv) the Second Review Order was irrational and unreasonable as it failed to take into account para 24(6), (8) and (9) of the InterGovernmental Committee Report ("IGC Report") which entitles the State of Sabah to receive grants based on the 40% formula as provided under art 112C and Part IV of the Tenth Schedule for the period from 1974 to 2021; and

(v) the Second Review Order was disproportionate to arts 112C and 112D of the FC particularly the application of the formula as set out in Part V of the Tenth Schedule thereto as the amount that would be derived from the 40% formula would be highly disproportionate to the amount now purportedly agreed upon in the Second Review Order.

[22] The following illustration was provided by SLS to summarise the relevant timeline of events in this matter:

The Case For The Federal Government

[23] The 1st Respondent's stand was that there was no outstanding payment due and owing to the State of Sabah between 1974 and the Second Review Order.

[24] This was premised on the 1st Respondent's further stand that:

(i) It had already paid the annual grants of RM26.7 million (which sum was based on the sum paid for the year 1973 under the First Review Order), which payments had been accepted by the State Government from 1974 until 2021;

(ii) The First Review Order was effective until it was revoked by the Second Review Order in 2022, which in turn was effective until it was revoked by the Third Review Order made on 22 November 2023; and

(iii) The sum of RM125.6 million, which was both agreed to as payment for the Year 2022 in the Second Review Order and the Third Review Order, was paid on 16 June 2022.

[25] In addition, the 1st Respondent's stand was that the review process was ongoing from 1974 up until the year 2021 between the 1st and 2nd Respondents concerning the amount to be granted by way of a substituted grant under art 112D(1) of the FC taking into account the consideration stipulated in art 112D(2) of the FC.

The Case For The State Government

[26] The 2nd Respondent took a somewhat neutral stand and contended that it had, at all material times, continuously pursued its rights to a review of Sabah Special Grant, that after the First Review Order and up until the year 2020, it had corresponded and or met with the 1st Respondent towards that purpose wherein there was an acknowledgement by the 1st Respondent that a review of Sabah Special Grant was necessary given that the one and only review was conducted in 1969.

[27] Despite this, according to the 2nd Respondent there was no agreement and or subsequent review to the First Review Order that resulted in a substitution of the First Review Order. As a result, the 2nd Respondent had received and continued to receive RM26.7 million for each of the consecutive years from 1973 until 2021.

[28] As the parties were unable to agree on a quantum for the new Sabah Special Grant and/or any outstanding payments due to the absence of a review of Sabah Special Grants since 1973, the 2nd Respondent averred that an "interim arrangement" was agreed upon which resulted in the Second and Third Review Orders.

[29] However, the 2nd Respondent asserted that this was on a "without prejudice" basis and pending further negotiations between the parties with the following express conditions:

(a) that the 2nd Respondent was entitled to rely on the original formula as stated in art 112C and Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the FC; and

(b) that the 2nd Respondent was entitled to recover any outstanding payments due to the absence of a review of Sabah Special Grants since 1973.

[30] The respective parties' cases would be revisited in the latter part of this judgment and considered on their merits as against the relevant constitutional provisions.

Preliminary Issues

[31] Before delving into the merits of the application, there were two interrelated issues raised by the 1st Respondent which merited this court's preliminary determinations.

Jurisdictional Point

[32] The first was a jurisdictional point.

[33] It was contended that the Court's jurisdiction to review under O 53 of the ROC 2012 was ousted given the divergence in the positions taken by the Federal Government and State Government with respect to the constitutional right of the State of Sabah for a review exercise under art 112D(3) and (4) of the FC and the 40% Entitlement for special grant each consecutive financial year from 1974 to 2021.

[34] It was submitted that the Federal Government and Sabah Government were at odds as regards the issue of whether there was an outstanding payment due to the absence of a review of Sabah Special Grants since 1973. Thus, although leave to commence judicial review proceedings had been brought by SLS, according to learned Senior Federal Counsel ("SFC"), the issue has evolved at the substantive stage into a dispute between the Federal Government and Sabah Government.

[35] Indeed, as set out earlier, the case for the 1st Respondent was that there was no outstanding payment for the Lost Years while the 2nd Respondent's case was that while it had accepted the RM26.7 million for the years from 1973 until 2021 and agreed to the "interim arrangement" in the form of the Second and Third Review Orders, it never waived its rights to the outstanding payments since 1973.

[36] Learned SFC submitted that this "dispute" fell within the original jurisdiction of the Federal Court under art 128 of the FC, reproduced below:

"(1) The Federal Court shall, to the exclusion of any other court, have jurisdiction to determine in accordance with any rules of court regulating the exercise of such jurisdiction:

(a) any question whether a law made by Parliament or by the Legislature of a State is invalid on the ground that it makes provision with respect to a matter with respect to which Parliament or, as the case may be, the Legislature of the State has no power to make laws; and

(b) disputes on any other question between States or between the Federation and any State.

(2) Without prejudice to any appellate jurisdiction of the Federal Court, where in any proceedings before another court a question arises as to the effect of any provision of this Constitution, the Federal Court shall have jurisdiction (subject to any rules of court regulating the exercise of that jurisdiction) to determine the question and remit the case to the other court to be disposed of in accordance with the determination.

(3) The jurisdiction of the Federal Court to determine appeals from the Court of Appeal, a High Court or a judge thereof shall be such as may be provided by federal law."

[37] The Federal Court case of Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [2020] 2 MLRA 1 was cited to contend that whilst all courts are empowered to interpret the FC under its different provisions, the Federal Court has exclusive jurisdiction to determine Federal and State disputes pursuant to art 128(1)(b) of the FC.

[38] The 1st Respondent had in fact already raised this issue in the leave application before the Federal Court. However, the Federal Court was not in favour of the argument, inter alia, holding that it was "obvious" that the appeal must involve some form of disagreement between the relevant parties and that since there was no claim by Sabah on its own behalf, it could not be said that there was a dispute between Sabah and the Federation (for art 128(1)(b) to apply).

[39] In revisiting the argument before this court, learned SFC submitted that the 2nd Respondent had become a party to the proceedings at the leave stage by virtue of O 53 r 8(1) of the ROC 2012. Thus, the 2nd Respondent's stance was not clear at that time as opposed to in the substantive application.

[40] Both SLS and the 2nd Respondent resisted the arguments by the 1st Respondent on this issue on the ground that notwithstanding the inclusion of the 2nd Respondent as a party in the application, it remained true that the State Government has not made any claim, nor has it been sued by, or sued the Federal Government as the inter-Governmental 'dispute' envisaged under cl (1)(b) of art 128.

[41] It is instructive to first reproduce in full what the Federal Court in Dato' Seri Anwar Ibrahim had stated on the jurisdiction of the Federal Court:

"[13] The general scheme of the FC is to empower all courts to interpret the constitution (Gin Poh Holdings Sdn Bhd v. The Government Of The State Of Penang & Ors [2018] 2 MLRA 547 at [35]-[36]). The power to interpret constitutional provisions is not exclusive to the Federal Court. 'The Federal Court is not a constitutional court, but as the final Court of Appeal on all questions of law, is the final arbiter on the meaning of constitutional provisions' (A Harding, Law, Government and the Constitution in Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Malayan Law Journal, 1996) at p 138).

[14] The jurisdiction of the Federal Court is of four kinds: appellate jurisdiction, original jurisdiction under art 128(1) of the FC, referral jurisdiction under art 128(2), and advisory jurisdiction under art 130 (Assa Singh v. MentriBesar Johore [1968] 1 MLRA 886, Kulasingam v. Public Prosecutor [1978] 1 MLRA 603). The exclusive original jurisdiction of the Federal Court is confined only to Federal-State disputes, disputes between states, and cases where the validity of a law is challenged on the ground that Parliament or a State Legislative Assembly had legislated on a matter on which it had no power to make laws. All other questions of constitutionality are within the jurisdiction of the High Court (Gin Poh Holdings Sdn Bhd at [36]).

[15] The limits of the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Federal Court are strictly construed. This is to preserve the role of the Federal Court as a final Court of Appeal on constitutional issues; 'to extend the exclusive original jurisdiction of the Federal Court to matters which are not expressly provided by the Constitution would apart from anything else, deprive aggrieved litigants of their right of appeal to the highest court in the land' (Rethana M Rajasigamoney v. The Government Of Malaysia [1984] 1 MLRA 233).

[16] Under the constitutional scheme, therefore, the Federal Court is generally a court of last resort for all constitutional questions. It is only in a narrow category of exceptional cases — those expressly stipulated in art 128(1) of the FC — that such questions must be determined by the Federal Court at first instance."

[42] The above statement of the Federal Court could not be any clearer. As learned SFC submitted, the Federal Court did hold that it has exclusive original jurisdiction when the matter involves Federal and State disputes. However, the Federal Court also went on to add that the High Court has jurisdiction to hear and decide on all other questions of constitutionality.

[43] In my considered view, the facts of the present case fell within those "other questions of constitutionality" for which this court was clothed with jurisdiction to adjudicate.

[44] Further, a careful reading of Justice Nallini's statement in the judgment of the Federal Court in Attorney General of Malaysia v. Sabah Law Society precluded the facts of the present case from falling within the dispute envisaged under cl (1)(b) of art 128.

[45] Her Ladyship held that:

"...art 128(1)(b) says that disputes 'between' the Federation and any State fall within the Federal Court's exclusive jurisdiction; it does not say that disputes affecting or relating to the Federation and any State fall within the Federal Court's exclusive jurisdiction. If the article is intended to impose a substantive restriction on the type of matters that must be brought only to the Federal Court, it would have used different words. The word 'between' suggests that what matters is that the parties to the suit are the Federation and any State not that the suit affects the Federation and/or any State;"

[Emphasis Added]

[46] The divergence in the stances taken by the Federal Government and the State Government as regards whether there was an outstanding payment for the Lost Years, in my view, did not amount to a 'dispute' within the contemplation of art 128(1).

[47] As held by Sarkaria J in the Supreme Court of India case of Gujarat State Co-operative Land Development Ltd v. PR Mankad & Anor [1979] AIR 1203:

"The term 'dispute' means a controversy having both positive and negative aspects. It postulates the assertion of a claim by one party and its denial by the other."

[48] As would be evident in the later part of this judgment, the divergence in the stances by the 1st and 2nd Respondents merely went to the differences in their respective understanding of arts 112C and 112D of the FC. This by itself was insufficient to oust this court's jurisdiction. To construe art 128 to apply to the facts and circumstances of the present case would be to apply a liberal interpretation of constitutional provisions that confer jurisdiction to the courts contrary to the general rule — see Dr Koay Cheng Boon v. Majlis Perubatan Malaysia [2012] 2 MLRA 23; Tan Sri Eric Chia Eng Hock v. PP [2006] 2 MLRA 556.

[49] Additionally, to agree with learned SFC's contentions on this issue would be to ignore the fact that the judicial review was brought by SLS, whose locus standi was challenged by the 1st Respondent to the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court (at the leave stage). Having successfully defended their standing, to invoke art 128 at this stage would not only have denied SLS of their rights to be heard on the merits of the substantive judicial review application but also derail the whole proceedings which at the time already taken three years since its filing.

[50] In contrast, and I found it to be highly significant, the fact that this issue was not raised by the 1st Respondent at the earliest possible time (ie after the close of the affidavits in March 2025) but only through the 1st Respondent's written submissions strongly suggested that this issue was not at all pivotal to their case in this judicial review.

The 2nd Respondent Not Being An "Appropriate" Party

[51] The second issue raised by the 1st Respondent had to do with the position taken by the 2nd Respondent in the judicial review and related to the 1st Respondent's arguments on art 128 discussed earlier.

[52] It was asserted that the 2nd Respondent's stand was "aligned" with SLS namely that the 2nd Respondent was entitled to rely on the original formula as stated in art 112C and Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the FC and to recover any outstanding payments due to the absence of a review of Sabah Special Grants since 1973.

[53] This, according to learned SFC, rendered the 2nd Respondent's inclusion as a party to the judicial review, "inappropriate" as it was argued that O 53 r 8(1) of the ROC 2012 applies (only) to persons wishing to be heard in opposition. It was submitted that this amplified the invocation of art 128(1)(b) of the FC.

[54] The Federal Court case of Majlis Agama Islam Selangor v. Bong Boon Chuen & Ors [2009] 2 MLRA 453 and the Court of Appeal case of Advance Synergy Capital Sdn Bhd v. The Minister Of Finance Malaysia & Anor [2011] 1 MLRA 477 were cited in support.

[55] I did not find these cases to be of any assistance to the 1st Respondent on the facts of the present case. Here, a High Court order was made on 20 July 2022 granting the 2nd Respondent leave to be joined as a party in the judicial review and for the 2nd Respondent "to be heard in all judicial review proceedings herein". This necessarily meant including the present substantive judicial review.

[56] The said Order was never appealed against and or set aside, and as such, was valid and must be obeyed — see Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Bandar Nusajaya Development Sdn Bhd [2016] 6 MLRA 103; Khaw Poh Chhuan v. Ng Gaik Peng & Yap Wan Chuan & Ors [1996] 1 MLRA 101. Thus, to accept the 1st Respondent's contention that the 2nd Respondent was an "inappropriate" party to the proceedings would be to completely ignore the said Order.

[57] In any event, from this court's own evaluation of the 2nd Respondent's averments in its affidavits and the submissions by learned State-Attorney General ("SAG"), it could not be said that the 2nd Respondent's position was "aligned" with SLS. The 2nd Respondent in fact opposed the order for certiorari which was the primary remedy sought by SLS in this application. This was sufficient for this court to exercise its wide discretion to hear the 2nd Respondent in this application.

[58] For the above reasons, I did not agree with the 1st Respondent's contention that this court's jurisdiction was ousted by art 128. I had therefore proceeded to consider the merits of the application.

This Court's Decision On The Merits

[59] The merits or otherwise of this application turned on the construction of art 112C read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule and Clauses (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D.

[60] It would therefore be appropriate to reproduce the relevant provisions under arts 112C and 112D:

"Article 112C. Special Grants and assignment of revenue to States of Sabah and Sarawak

(1) Subject to the provisions of art 112D and to any limitation expressed in the relevant section of the Tenth Schedule:

(a) the Federation shall make to the States of Sabah and Sarawak in respect of each financial year the grants specified in Part IV of that Schedule; and

(b) each of those States shall receive all proceeds from the taxes, fees and dues specified in Part V of that Schedule, so far as collected, levied or raised within the States, or such part of those proceeds as is so specified.

(2) The amounts required for making the grants specified in the said Part IV, and the amounts receivable by the State of Sabah or Sarawak under s 3 or 4 of the said Part V, shall be charged on the Consolidated Fund; and the amounts otherwise receivable by the State of Sabah or Sarawak under the said Part V shall not be paid into the Consolidated Fund.

(3) In art 110, Clauses (3A) and (4) shall not apply to the State of Sabah or Sarawak.

(4) Subject to Clause (5) of art 112D, in relation to the State of Sabah or Sarawak Clause (3B) of art 110:

(a) shall apply in relation to all minerals, including mineral oils; but

(b) shall not authorize Parliament to prohibit the levying of royalties on any mineral by the State or to restrict the royalties that may be levied in any case so that the State is not entitled to receive a royalty amounting to ten per cent ad valorem (calculated as for export duty).

Article 112D. Reviews of special grants to States of Sabah and Sarawak

(1) The grants specified in s 1 and subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule, and any substituted or additional grant made by virtue of this Clause, shall at the intervals mentioned in cl (4) be reviewed by the Governments of the Federation and the States or State concerned, and if they agree on the alteration or abolition of any of those grants, or the making of another grant instead of or as well as those grants or any of them, the said Part IV and Clause (2) of art 112C shall be modified by order of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong as may be necessary to give effect to the agreement:

Provided that on the first review the grant specified in subsection (2) of s 1 of the said Part IV shall not be brought into question except for the purpose of fixing the amounts for the ensuing five years.

.....

(3) The period for which provision is to be made on a review shall be a period of five years or (except in the case of the first review) such longer period as may be agreed between the Federation and the States or State concerned; but any order under cl (1) giving effect to the results of a review shall continue in force after the end of that period, except in so far as it is superseded by a further order under that Clause.

(4) A review under this Article shall not take place earlier than is reasonably necessary to secure that effect can be given to the results of the review from the end of the year 1968 or, in the case of a second or subsequent review, from the end of the period provided for by the preceding review; but, subject to that, reviews shall be held as regards both the States of Sabah and Sarawak for periods beginning with the year 1969 and with the year 1974, and thereafter as regards either of them at such time (during or after the period provided for on the preceding review) as the Government of the Federation or of the State may require."

[61] Subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule which provides for special grants to states of Sabah and Sarawak reads as follows:

"(1) In the case of Sabah, a grant of amount equal in each year to two-fifths of the amount by which the net revenue derived by the Federation from Sabah exceeds the net revenue which would have been so derived in the year 1963 if:

(a) the Malaysia Act had been in operation in that year as in the year 1964; and

(b) the net revenue for the year 1963 were calculated without regard to any alteration of any tax or fee made on or after Malaysia Day,

("net revenue" meaning for this purpose the revenue which accrues to the Federation, less the amounts received by the State in respect of assignments of that revenue)."

[62] The questions for this court in this judicial review were twofold:

(i) whether the review conducted by the Federal Government and Sabah Government on 14 February 2022 with the ensuing results contained in the Second Review Order complied with the constitutional duties imposed upon and powers vested in them under the FC at art 112C read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule and Clauses (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D; and

(ii) if the Governments had failed to comply with their duties and to properly exercise their powers, what was the effect of that failure in relation to the Second Review Order.

[63] SLS had invited this court to consider and approach the construction of these constitutional provisions with the historical facts and the constitutional foundation documents in mind.

[64] These "constitutional foundation documents" included the following:

(i) Cobbold Commission Report (Cobbold Report);

(ii) IGC Report;

(iii) Malaysia Agreement 1963 ("MA 63"); and

(iv) Malaysia Act 1963.

[65] It was highlighted by learned counsel for SLS that the provisions in the FC comprise part of the conditions that led to the people living in North Borneo agreeing to the formation of Malaysia and that these constitutional foundation documents attest to this fact. Thus, they could not be divorced from the court's consideration when construing these constitutional provisions.

[66] While not disputing the veracity of the historical facts as set out in SLS' affidavit, the 1st Respondent rather inexplicably downplayed their significance, stating that:

"... the history of formation of the Federation of Malaysia is not a factor to be taken into account in this judicial review application."

[67] With respect, the 1st Respondent's stand was against the decision by the apex court in Indira Gandhi Mutho v. Pengarah Jabatan Agama Islam Perak & Ors And Other Appeals [2018] 2 MLRA 1, that:

"[29] A constitution must be interpreted in light of its historical and philosophical context, as well as its fundamental underlying principles."

[68] This sentiment was later echoed by the Court of Appeal in Mahisha Sulaiha Abdul Majeed v. Ketua Pengarah Pendaftaran & Ors And Another Appeal [2022] 6 MLRA 59 which held as follows:

"[12] The historical background is important in determining the clear intention of the framers of the Constitution. It is well-established that a constitution must be interpreted in light of its historical and philosophical context, as well as its fundamental underlying principles. This is because every utterance must be construed in its proper context, considering the historical background and the purpose for which the utterance was made. The background of a constitution is an attempt, at a particular moment in history, to lay down an enduring scheme of Government in accordance with certain moral and political values. Interpretation must take these purposes into account. (See: Alma Nudo Atenza v. PP & Another Appeal [2019] 3 MLRA 1)."

[69] It was with the above authorities in mind that this court considered the historical facts as set out by SLS in their affidavit. These facts provided the necessary context as to how the constitutional provisions came into being and how they were to be construed. As noted earlier, these facts were not disputed by the 1st Respondent.

Relevant Historical Facts

[70] The MA63 came into being on 9 July 1963. It was entered into between the Federation of Malaya, United Kingdom, acting as Colonial Governments of Sabah and Sarawak, and Singapore. The States of Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore were federated with Federation of Malaya, and the Federation of Malaya was later renamed as the Federation of Malaysia.

[71] The MA63 together with all the Annexures thereto was registered by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on 21 September 1970 with the United Nations and endorsed by the United Nations (UN) as an International Treaty and entered in the List Treaties as Registered with the UN as No 10760 in the United Nations — Treaty Series.

[72] The 40% Entitlement was one of the rights granted to Sabah as promised under the MA63. This right, amongst others, was contained in the IGC Report and the reason for the IGC was that the Cobbold Commission found that roughly only one-third of the people in these former colonies were in favour of the formation of Malaysia, one-third were willing to accept the Malaysia idea provided certain specific safeguards and rights were implemented for Sabah and Sarawak as conditions for formation of Malaysia, and the last one-third was a mixed group with the larger part dead set against the idea and wanted independence first and the other part that can be persuaded with assurances in place.

[73] In MA63 at Article II, the Government of the Federation of Malaya promised that Malaysia Act would be enacted by the Malayan Parliament to come into force on Malaysia Day, which was postponed to 16 September 1963.

[74] The financial provisions, including the duty to pay the 40% Entitlement, was contained in Malaysia Act and these were enacted as amendments in the Federal Constitution to constitutionalise the promise to make the 40% Entitlement to the State of Sabah that was at the same time federated with Malaya, Sarawak, and Singapore.

[75] In MA63 at Article VIII, it was also promised by the Governments of Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak and further assured to the peoples of Sabah and Sarawak that such rights in Chapter 3, inter alia, of the IGC Report, which included the 40% Entitlement, would be implemented.

The Constitutional Foundation Documents

[76] The case of Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop Of Kuala Lumpur v. Menteri Dalam Negeri & Ors [2014] 4 MLRA 205 concerned an application for leave to appeal to the Federal Court under s 96(a) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964.

[77] Among others, the proposed leave questions included the following 'constitutional law question':

"Whether in the construction of art 3(1) it is obligatory for the Court to take into account the historical constitutional preparatory documents, namely, the Reid Commission Report 1957, the White Paper 1957, and the Cobbold Commission Report 1962 (North Borneo and Sarawak) that the declaration in art 3(1) is not to affect freedom of religion and the position of Malaya or Malaysia as a secular state?

[78] The Federal Court cited its own decision in Datuk Hj Mohammad Tufail Mahmud & Ors v. Dato' Ting Check Sii [2009] 1 MLRA 602 and reminded that:

"The various documents, being the initial foundation in the formation of the Federation, must not be cast aside as mere historical artifacts."

[79] In Datuk Hj Mohammad Tufail Mahmud, the Federal Court heard arguments on two leave questions namely, (i) whether an advocate and solicitor from Peninsular Malaysia was entitled to appear as counsel in an appeal to be heard in Putrajaya arising from a matter originating from the High Court in Sarawak and Sabah at Kuching; and (ii) whether an advocate from Sarawak was entitled to appear as counsel in an appeal to be heard by the Court of Appeal in Putrajaya arising from a matter originating from the High Court in Sarawak and Sabah at Kuching.

[80] In coming to its decision on these issues, the Federal Court noted that "the Cobbold Commission was created to ascertain the views of the people of the Borneo States" and that the "report showed that the people had fears of substitution of one colonisation with another; fear of being taken over by the then Federation of Malaya; fears of the submersion of the individualities of North Borneo and Sarawak within the then Federation of Malaya."

[81] The Federal Court went on to note that:

"[17] These fears were ultimately addressed by the formation of the InterGovernmental Committee (IGC) on which the British, Malaya (now properly known as Semenanjung Malaysia), North Borneo and Sarawak Governments were represented. Its task was to work out the future constitutional arrangements, including safeguards for the special interests of North Borneo and Sarawak relying on the Cobbold Commission Report...

[18] Following the IGC Report, the Malaysia Agreement was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore and signed on 9 July 1963 (see p 3 of the Malaysia Agreement, see also The Government Of The State Of Kelantan v. The Government Of The Federation Of Malaya And Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj [1963] 1 MLRH 160)."

[82] More importantly, the Federal Court recognised that:

[23] It must be noted that without such recommendations in the IGC, Cobbold Commission and the Malaysia Agreement, there may not be a Malaysia (The Birth of Malaysia (3 Ed 2008), Malaysia Singapore and Hong Kong, Sweet & Maxwell Asia at p 11)."

[Emphasis Added]

[83] The historical facts and the constitutional foundation documents would be relevant as this court considered the counter-arguments by the parties on the issues raised. This included the submissions for the 1st Respondent that the legal right of the State of Sabah as provided under art 112C read with art 112D of the FC could not be extended based on the recommendation in the IGC Report and the Cobbold Report.

Did The Federal Government And The Sabah Government Fail To Comply With Their Duties And To Properly Exercise Their Powers?

[84] As a starting point, it must be noted that it was never the 1st Respondent's stand that the State of Sabah was not ever entitled to the 40% Entitlement under art 112C read with subsection (1) of s 2 of Part IV of the Tenth Schedule of the FC. The 1st Respondent's stand was that the 40% Entitlement was not an immutable right but subject to review by the Federal Government and the State of Sabah based on the scope of art 112D of the FC.

[85] Neither was it the 1st Respondent's case that the formula expressed in the second declaratory relief sought herein was incorrect or erroneous. The 1st Respondent had no arguments with the said formula. The 1st Respondent's stand was simply that the manner in which the special grant based on the 40% formula was to be calculated had been rendered "academic".

[86] There was also no dispute that after the First Review Order 1970, the next review order ie the Second Review Order was made in 2022, after the lapse of 48 years.

[87] It was submitted by learned counsel for SLS that the plain language used in art 112D expresses the intent that by using the word 'shall', it is imperative or mandatory, rather than permissive or optional. As a rule of thumb, prima facie, 'shall' means that it is imperative. However, the word would also take its meaning from the context in which it is used — see Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad v. Mohd Afrizan Husain [2022] 4 MLRA 547 where the Federal Court held that the word 'shall' in r 16.11(2) of Bursa's ACE Market Listing Requirements was used in a 'directory' sense.

[88] It was further submitted that Clauses (1), (3) and (4) of art 112D use the imperative 'shall' when stipulating that the two Governments shall conduct the review.

[89] Clause (1) states, the special grant 'made by virtue of this Clause, shall at the intervals mentioned in cl (4) be reviewed by' the two Governments.

[90] Clause (3) in stipulating the 'period for which provision is to be made on a review shall be a period of five years or (except in the case of the first review) such longer period as may be agreed between' the two Governments 'but any order under cl (1) giving effect to the results of a review shall continue in force after the end of that period, except in so far as it is superseded by a further order under that Clause.'

[91] The imperative nature of the constitutional intent is further seen in cl (4) of art 112D which reads as follows:

"(4) A review under this Article shall not take place earlier than is reasonably necessary to secure that effect can be given to the results of the review from the end of the year 1968 or, in the case of a second or subsequent review, from the end of the period provided for by the preceding review; but, subject to that, reviews shall be held as regards both the States of Sabah and Sarawak for periods beginning with the year 1969 and with the year 1974, and thereafter as regards either of them at such time (during or after the period provided for on the preceding review) as the Government of the Federation or of the State may require."

[Emphasis Added]

[92] According to SLS, cl (4) means the following:

(i) that the first review is mandated to be held for the period of five years from the beginning of the year 1969;

(ii) that the period for annual payments of the special grant made under the first review would therefore be completed by the end of the year 1973; and

(iii) that therefore, the second review must be held to make the special grant for the succeeding period beginning from the year 1974. And after the first and second reviews, the Federal Government and Sabah Government would hold such reviews to make the special grant as either of them may require.

[93] I found merits in SLS' reading of this provision. As noted earlier in this judgment, case law has long held that the court must have regards to not only the historical facts but also the constitutional foundation documents when interpreting the constitutional provisions.

[94] In this respect, it was relevant to note the recommendations by the IGC in its Report to the Governments of the United Kingdom and Malaya that the special grant to the States of Sabah and Sarawak have to be included as amendments to Part VII of the then Malayan Constitution at the formation of Malaysia.

[95] Paragraph 24(8) of the IGC Report stipulates that:

"Subject to the provisions of review made in subparagraph (9) below, North Borneo should receive each year a grant equal to 40% of any increase in Federal revenue derived from North Borneo and not assigned to the State over the Federal revenue which would have accrued in 1963 if these financial arrangements had been in force in that year. The sum payable would be calculated on the basis of actual revenue received in each year."

[96] At subparagraphs (9)(iii) and (iv) of Paragraph 24 of the IGC Report, it was recommended by the IGC as follows:

"(iii) The first review should be undertaken in time to enable the assessor's recommendations to be implemented with effect from the beginning of the sixth year after the application of Part VII of the Constitution to the Borneo States, and once implemented should remain in force until superseded by implementation of the recommendations of the second assessor.

(iv) The second review should similarly be undertaken in time to enable the assessor's recommendations to be implemented with effect from the beginning of the eleventh year and should relate to the ensuing period of five years or such longer period as might be agreed upon by the parties concerned, and once implemented should remain in force until the end of that period and thereafter until superseded by implementation of the recommendations of a subsequent assessor."

[97] In my considered view, SLS' reading of cl (4) was consistent with the constitutional intent as illustrated in the recommendations in the IGC Report.

[98] As noted earlier, learned SFC has cautioned against relying on the recommendations in the IGC Report. Citing the Federal Court's decision in Keruntum Sdn Bhd v. The Director of Forest & Ors [2018] 2 SSLR 167; [2018] 5 MLRA 175, it was submitted that SLS could not attempt to enforce terms relating to financial provisions which are not encompassed in the FC on the basis that they had been recommended in the IGC Report and the Cobbold Report.

[99] In Keruntum, an application was made to review the Federal Court's earlier judgment on the basis that there was a coram failure of the Federal Court's panel which did not consist of a judge of Borneo and therefore with Bornean experience. According to the applicant, His Lordship Hasan Lah FCJ, who sat and penned the judgment of the Federal Court, was not with Bornean judicial experience.

[100] The applicant's main thrust of argument was grounded on the application of the IGC Report whereby the applicant contended that art 128 of the FC, read together with paragraph 26(4) of the IGC Report stipulate that a Bornean dispute before the Federal Court must be decided by a panel which includes at least one judge with Bornean judicial experience. Reference was made to paragraph 26(4) of the IGC Report which recommended the following:

"(4) The domicile of the Supreme Court should be in Kuala Lumpur. Normally at least one of the Judges of the Supreme Court should be a judge with Bornean judicial experience when the Court is hearing a case arising in a Borneo State; and it should normally sit in a Borneo State to hear appeals in cases arising in that State."

[101] As regards the arguments on the IGC recommendation, the Federal Court stated as follows:

"(c) after the IGC Report, the CJA 1964 which came into effect from 16 March 1964 and specifically s 74 CJA 1964 remains unamended. Thus, reading s 74 CJA 1964 together with art 122 of the FC clearly does not impose a legal requirement that the Federal Court, when hearing or disposing of cases, must consist of at least one judge with Bornean judicial experience [17].