Federal Court, Putrajaya

Abdul Rahman Sebli CJSS, Zabariah Mohd Yusof, Rhodzariah Bujang, Abdul Karim Abdul Jalil, Ahmad Terrirudin Mohd Salleh FCJJ

[Civil Appeal Nos: 02(f)-22-07-2024(W) & 02(f)-23-07-2024(W)]

2 October 2025

Contract: Consideration — Restitution — Equitable doctrine of total failure of consideration — Invocation and application of said doctrine — Whether case of Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd wrongfully conflated right of rescission of contract with right to seek restitution of monies paid and received — Whether applicable test for total failure of consideration was not whether promisee had received a specific benefit but whether promisor had performed any part of contractual duties in respect of which payment was due

The present two appeals raised novel points of law concerning the Malaysian position on the common law restitutionary doctrine of total failure of consideration in light of the Federal Court's prior rulings in Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd ("Berjaya Times Square") and Damansara Realty Bhd v. Bungsar Hill Holdings Sdn Bhd & Anor ("Damansara Realty"). The present appeals, in essence, concerned the Assignment Agreements involving four vacant parcels of land in the District of Gombak, Mukim Rawang, Selangor ("Rawang 4") assigned by the Plaintiffs/Applicants to the Defendant/Respondent for a consideration. These lands were acquired through a Sale and Purchase Agreement ("SPA") between the Plaintiffs and a land developer, DA Land Sdn Bhd ("DA Land"), which itself subsequently became involved in a broader sequence of separate proceedings involving the Plaintiffs on one hand and the Defendant on the other. The proceedings between the Plaintiffs and Defendant in the courts below proceeded on the legality of these contracts as the central issue for judicial determination, and the leave questions framed by the Plaintiffs primarily concerned the parties' rights and liabilities arising from these contractual arrangements. The Plaintiffs filed Appeal No 23 against the Court of Appeal's dismissal of their appeal and Appeal No 22 against the Court of Appeal's decision allowing the Defendant's appeal against the High Court's dismissal of the counterclaim.

The Plaintiffs were granted leave to appeal to this Court on the following questions of law: (1) whether the doctrine of total failure of consideration, as an equitable doctrine, could be invoked by the Defendant to recover, from the Plaintiffs, a sum of RM23,000,000.00, which sum had previously been declared by the High Court in a related suit (affirmed on appeal) as non-recoverable, as it comprised part of an illegal moneylending transaction engaged in by the Defendant, and in which proceedings the Defendant was declared to be an unlicensed moneylender; (2) whether the doctrine of a total failure of consideration, as an equitable doctrine, could be invoked by the Defendant to recover a sum of RM23,000,000.00 from the Applicants when the Defendant was held by the High Court in the present case to be the party who had caused the loss and on which "loss" he had based his claim of a total failure of consideration; (3) whether the doctrine of a total failure of consideration could apply where there had been performance or part-performance of the contract, which was the assignment of a sale agreement by the Plaintiffs to the Defendant, pursuant to which the Defendant made part-payment thereof and received the benefit of the assignment; (4) whether the true test of a total failure of consideration was as stated in Stocznia Gdanska SA v. Latvian Shipping Co ("Stocznia Gdanska SA"), namely "whether the promisor has performed any part of the contractual duties in respect of which payment is due" and not the test of "whether the party in default has failed to perform his promise in its entirety" as stipulated by the Federal Court in Berjaya Times Square; (5) whether the case of Berjaya Times Square relied on by the Court of Appeal had wrongfully conflated the right of rescission of a contract with the right to seek restitution of monies paid and received (which was independent of rescission or termination of a contract) and was, therefore, not truly classifiable as an authority for the doctrine of restitution based on a total failure of consideration; and (6) whether, on its true principle, the doctrine of a total failure of consideration had no application where there had been only a partial failure of performance or the claimant had derived some benefit from the contract so that he was restricted to an action in damages for breach of contract as opposed to restitution, per Phang Quee v. Virutthasalam and Baltic Shipping Co v. Dillon.

Held (allowing both the plaintiffs/applicants' appeals):

(1) The Defendant was, on the facts, not entitled to pursue recovery based on the equitable doctrine of total failure of consideration against the Plaintiffs, the amount of RM23,000,000.00, which amount had previously been declared by the High Court in two suits (ie, Suits 396 and 88), as non-recoverable because it comprised part of an illegal moneylending transaction engaged in by the Defendant and in which proceedings the Defendant was declared to be an unlicensed moneylender. Similarly, the Defendant was not entitled to pursue recovery on the same equitable principle for the same amount when the High Court found the Defendant in the main suit from which the present appeals originated as the party who had caused the loss and on which loss he had based his claim of total failure of consideration. Given the background, the Court of Appeal could not, in equity, order the Plaintiffs to refund RM23,000,000.00 to the Defendant. The Court of Appeal's failure to give any consideration to - (i) the relevant surrounding circumstances of the Defendant's use of the RM23,000,000.00 in his subsequent unilateral transaction with DA Land for three of the lots in Rawang 4 ("Rawang 3"), after having entered into an Assignment Agreement and Supplemental Assignment Agreement with the Plaintiffs for Rawang 4; and (ii) the effect of the High Court judgments in Suits 396 and 88 on the Defendant - constituted a fatal misdirection warranting appellate intervention. Therefore, Questions 1 and 2 were answered in the negative. (paras 131-132)

(2) Question 3, in essence, sought a determination as to whether a total failure of consideration might be recognised in law where there had been complete or partial performance from which the Defendant had received the benefit of the assignment arising from his purported part payment under the contract. Question 6 was a derivative of Question 3 and similarly sought a determination on whether a total failure of consideration might be recognised in law where there had been a partial failure of performance or where the Defendant had derived some benefit under the contract, thereby entitling him to claim restitution. In that context, Questions 3 and 6 might be considered together as they entailed a cause-based inquiry and an effect-based inquiry into the doctrine of total failure of consideration. In fact, the questions could have been merged. Read together, they focused on the Plaintiffs' performance under the Assignment Agreement and Supplemental Assignment Agreement, and the purported benefit, if any, received by the Defendant under the contracts. (para 134)

(3) In the instant case, the Plaintiffs had done everything on their part under the contracts. The Defendant's contention that the Assignment Agreement and Supplemental Assignment Agreement were impossible to complete was without merit. There was no total failure of consideration as there had been performance or part performance by the Plaintiffs of their contractual duties in respect of which payment was due under the Assignment Agreement, and the Defendant had derived benefit from the same. Hence, the Court of Appeal's finding that there was a total failure of consideration was erroneous and could not be sustained. As there was no total failure of consideration and no basis for the Court of Appeal to make a finding of unconscionability against the Plaintiffs, the Defendant had breached the Assignment Agreement by entering into an SPA with DA Land for Rawang 3. This transaction was subsequently held by the High Court in Suits 396 and 88 to amount to an illegal moneylending arrangement and was therefore unenforceable. As a result, the Defendant lost all rights, interest and title to the lands in Rawang 3, without which Rawang 4 could not exist. Through the aforesaid actions, the Defendant had deprived the Plaintiffs of the benefit they were entitled to as consideration for assigning their rights to Rawang 4, namely RM2,500,000.00 which represented their investment in Rawang 4. The Plaintiffs suffered this loss due to the Defendant's breach of the Assignment Agreement and the Defendant's unilateral dealings with DA Land. Following the Defendant's breach, no investment in Rawang 4 could ever materialise. Therefore, in the premises, Questions 3 and 6, read and considered collectively, must be answered in the negative. (paras 151-155)

(4) As for Questions 4 and 5, the judicial focus of the inquiry must remain on the performance of the anticipated promise which formed the basis for the transfer of the relevant benefit or for which payment was due or made. Therefore, the law took a different course following Berjaya Times Square and Damansara Realty insofar as the doctrine of total failure of consideration was concerned, and conflating it with the right to rescind or terminate a contract. Those rulings conflated the doctrine of total failure of consideration for recovery of monies paid with recovery for breach of contract based upon termination or rescission. Accordingly, those rulings left the application of the doctrine of total failure of consideration in a state of uncertainty of the principles and tests applicable for: (i) rescission or termination of a contract for breach; and (ii) restitution in cases of a total failure of consideration. The law thus required clarification. Upon careful analysis and anxious reflection, the Court was of the considered view that Berjaya Times Square could no longer be regarded as good law. In the premises, Questions 4 and 5 were answered in the affirmative. (paras 164-166)

(5) In the upshot, the legal position could be stated as follows. The expression "rescission" was commonly used in two different contexts. On the one hand, it might denote the process by which a contract, containing an inherent cause of invalidity, was set aside in such a way that not only did the contract cease to exist, but it was deemed never to have existed. This process was more properly described as "rescission ab initio" and was the more correct usage of the term "rescission". An example of this was where a contract was set aside on the ground that it was induced by misrepresentation. On the other hand, the expression "rescission" might also be used to describe the situation where a contract that was otherwise entirely valid, containing no inherent cause of invalidity, suffered from a serious breach or where the innocent party treated the breach as a repudiation and accepted it, thereby bringing the contract to an end and releasing both parties from further obligations. This process was more properly described as "rescission for breach" or "termination". In this situation, there was no doubt that the contract subsisted until the moment of termination. For a breach to have the effect of entitling the innocent party to terminate the contract, it must be either: (i) a breach of a condition; or (ii) a sufficiently serious breach of an innominate/intermediate term; or (iii) a repudiation of the contract. The legal principles governing the award of restitutionary remedies had no application in determining whether a contract should be terminated for breach. The law of restitution and unjust enrichment became relevant after a contract had been discharged, rescinded, or terminated. A claim for restitution would be available when there was a total failure of consideration. The applicable test for total failure of consideration was not whether the promisee had received a specific benefit but rather whether the promisor had performed any part of the contractual duties in respect of which payment was due (Stocznia Gdanska SA). Hence, the Court of Appeal misdirected itself in concluding that the Plaintiffs were liable to return the sum of RM23,000,000.00 to the Defendant and that the Plaintiffs were not entitled to claim the remaining RM2,500,000.00 under the Assignment Agreement and Supplemental Assignment Agreement from the Defendant. The conclusions reached could not be justified in law and in fact, and they warranted appellate intervention. (paras 175-176)

Case(s) referred to:

Araprop Development Sdn Bhd v. Leong Chee Kong & Anor [2007] 2 MLRA 673 (refd)

Asia Pacific Higher Learning Sdn Bhd v. Majlis Perubatan Malaysia & Anor [2020] 1 MLRA 683 (refd)

Asian International Arbitration Centre v. One Amerin Residence Sdn Bhd & Ors And Another Appeal [2025] 3 MLRA 83 (refd)

Baltic Shipping Co v. Dillon [1993] 111 ALR 289 (folld)

Barnes v. Eastenders Cash & Carry Plc And Others [2015] AC 1 (refd)

Black-Clawson International Ltd v. Papierwerke Waldhof-Aschaffenburg AG [1975] AC 591 (refd)

Benzline Auto Pte Ltd v. Supercars Lorinser Pte Ltd And Another [2018] 1 SLR 239 (refd)

Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd [2009] 3 MLRA 1 (overd)

Bickerton v. Walker [1885] 31 Ch D 151 (refd)

Biswick v. Biswick [1968] AC 58 (refd)

British Movietonews Ltd v. London And District Cinemas Ltd [1952] AC 166 (refd)

Chor Phaik Har v. Farlim Properties Sdn Bhd [1994] 1 MLRA 356 (refd)

DA Land Sdn Bhd v. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong [2018] 2 MLRH 557 (refd)

Damansara Realty Bhd v. Bungsar Hill Holdings Sdn Bhd & Anor [2012] 1 MLRA 311 (distd)

Davis v. Johnson [1978] 1 All ER 841 (refd)

Dream Property Sdn Bhd v. Atlas Housing Sdn Bhd [2015] 2 MLRA 247 (refd)

Fibrosa Spolka Akcyjna v. Fairbairn Lawson Combe Barbour Ltd [1943] AC 32 (refd)

Foo Loke Ying & Anor v. Television Broadcasts Ltd & Ors [1985] 1 MLRA 635 (refd)

French Marine v. Compagnie Napolitaine d'Eclairage et de Chauffage par le Gaz [1921] 2 AC 494 (refd)

Goh Yew Chew & Anor v. Soh Kian Tee [1969] 1 MLRA 357 (refd)

Hong Kong Fir Shipping Co Ltd v. Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [1962] 2 QB 26 (refd)

Hunter v. Canary Wharf Ltd [1997] 2 WLR 684 (refd)

James Buchanan & Co Ltd v. Babco Forwarding And Shipping (UK) Ltd [1977] 1 ALL ER 518 (refd)

Jamshed Khodaram Irani v. Burjorji Dhurjibhai AIR [1915] PC 83 (refd)

Johnson & Anor v. Agnew [1980] AC 367 (refd)

Johor Coastal Development Sdn Bhd v. Constrajaya Sdn Bhd [2005] 1 MLRA 393 (refd)

Kartar Singh v. Pappa [1954] 1 MLRH 69 (refd)

Letitia Bosman v. PP & Other Appeals [2020] 5 MLRA 636 (refd)

Lim Ah Moi v. AMS Periasamy Suppiah Pillay [1997] 1 MLRA 366 (refd)

Lim Kar Bee v. Duofortis Properties (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 213 (refd)

Lim Swee Choo & Anor v. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong & Another Appeal [2024] 4 MLRA 623 (refd)

Lim Swee Choo & Satu Lagi lwn. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong [2022] MLRHU 928 (refd)

Linden Gardens Trust Ltd v. Lenesta Sludge Disposals Ltd [1994] 1 AC 85 (refd)

Ling Peek Hoe & Anor v. Ding Siew Ching And Another Appeal [2017] 4 MLRA 372 (refd)

LSSC Development Sdn Bhd v. Thomas Iruthayam & Anor [2007] 1 MLRA 121 (refd)

Mahiaddin Md Yasin v. PP [2024] 6 MLRA 914 (refd)

Marley v. Rawlings [2012] EWCA Civ 61 (refd)

Merong Mahawangsa Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Dato' Shazryl Eskay Abdullah [2015] 5 MLRA 377 (refd)

Metramac Corporation Sdn Bhd v. Fawziah Holdings Sdn Bhd [2006] 1 MLRA 666 (folld)

Moses v. Macferlan [1760] 2 Burr 1005 (refd)

Muschinski v. Dodds [1985] 160 CLR 583 (refd)

Ng Hoe Keong & Ors v. OAG Engineering Sdn Bhd & Ors [2022] 4 MLRA 535 (refd)

Obata-Ambak Holdings Sdn Bhd v. Prema Bonanza Sdn Bhd And Other Appeals [2024] 6 MLRA 1 (refd)

Offer-Hoar v. Larkstore Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 1079 (refd)

Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong v. DA Land Sdn Bhd & Ors [2018] 5 MLRA 648 (refd)

Phang Quee v. Virutthasalam & Ors [1965] 1 MLRA 304 (folld)

Photo Production Ltd v. Securicor Transport Ltd [1980] 1 All ER 556 (refd)

Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai & Anor v. Muziadi Mukhtar [2019] 6 MLRA 307 (refd)

R (On The Application Of Quintavalle) v. Secretary Of State For Health [2003] 2 All ER 113 (refd)

Rasiah Munusamy v. Lim Tan & Sons Sdn Bhd [1985] 1 MLRA 150 (refd)

Re Spectrum Plus Ltd (In Liquidation) [2005] 2 AC 680 (refd)

Roberts v. Jules Consultancy Ltd [2021] NZCA 303 (refd)

Roxborough And Others v. Rothmans Of Pall Mall Australia Ltd [2001] 185 ALR 335 (refd)

Senanayake v. Annie Yeo [1965] 1 MLRA 7 (refd)

Shanghai Tongji Science & Technology Industrial Co Ltd v. Casil Clearing Ltd [2004] HKCU 380 (refd)

Stocznia Gdanska SA v. Latvian Shipping Co [1998] 1 WLR 574 (folld)

Tan Ah Tong v. Che Pee Saad & Anor And Other Cases (Consolidated) [2009] 4 MLRA 341 (refd)

Tekun Nasional v. Plenitude Drive (M) Sdn Bhd And Another Appeal [2021] 6 MLRA 677 (folld)

Tebin Mostapa v. Hulba-Danyal Balia & Anor [2020] 4 MLRA 394 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Chew Thai Kay & Anor [2022] 2 MLRA 178 (refd)

Triple Zest Trading & Suppliers Sdn Bhd & Ors v. Applied Business Technologies Sdn Bhd [2024] 1 MLRA 144 (refd)

United Hokkien Cemetries Penang v. The Board Majlis Perbandaran Pulau Pinang [1979] 1 MLRA 95 (refd)

White v. Blackmore [1972] 3 All ER 158 (refd)

White v. Jones [1993] 3 All ER 481 (refd)

Yeap Hock Seng @ Ah Seng v. Minister For Home Affairs, Malaysia & Ors [1975] 1 MLRH 378 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Contracts Act 1950, ss 40, 56(1), 66, 71

Evidence Act 1950, s 103

Other(s) referred to:

Charles Mitchell, Paul Mitchell & Stephen Watterson, Goff & Jones on Unjust Enrichment, [2022], (10th Edn), Sweet & Maxwell, p 467

Cheong May Fong & Lee Yin Harn, Civil Remedies, (2nd Edn), [2016], Sweet & Maxwell, pp 36-39, paras 2.056, 2.059

David Fung Yin Kee, Berjaya Times Square Revisited: What's in a Name?, [2019], Journal of the Malaysian Judiciary, pp 169-203, 188-189, paras 44, 77

Edwin Peel, Treitel on The Law of Contract, (16th Edn), [2025] Sweet & Maxwell

Ewan McKendrick, Contract Law — Text Cases and Materials, (11th Edn), [2024], Oxford University Press

Hugh Beale, Chitty on Contracts, (35th Edn), [2024], Sweet & Maxwell

J W Carter, Fundamental Breach and Discharge of Breach under the Contract Act 1950 (Malaysia), [2011], Journal of Contract Law, Vol 28, pp 85-100

Lord Devlin, The Treatment of Breach of Contract, [1966], The Cambridge Law Journal, 24(2), pp 192-215

Lord Reid, The Judge as Lawmaker, [1972], Journal of the Society of Public Teachers of Law, Vol 12, p 23

Lord Sales, Statutory Interpretation in Theory and Practice, [2025], p 16

Low Weng Tchung, The Law of Restitution and Unjust Enrichment in Malaysia, [2015], LexisNexis, pp 61, 430, 465, 466, 467, 468, paras 2.25, 6.91, 6.134, 6.137

Sultan Azlan Shah Law Lectures II, Rule of Law, Written Constitutions & The Common Law Tradition, [2011], Sweet & Maxwell, p 387

Visu Sinnadurai, Law of Contract, (4th Edn), [2011], LexisNexis, pp 1031-1042, 1046-1047

Visu Sinnadurai, Law of Contract, (5th Edn), [2023], LexisNexis, Vol 2 pp 1161-1165

Counsel:

For the applicants: Cyrus V Das (Low Weng Tchung, Jaden Phoon Wai Ken & Adeline Tan Shu Phing with him); M/s Adeline, Phoon & Co

For the respondent: Alfred Lai Choong Wui (Toh Mei Swan, Ho Weng Sze, Yew Jing Yi, & Jonathan Gerard with him); M/s Alfred Lai & Partners

[For the Court of Appeal judgment, please refer to Lim Swee Choo & Anor v. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong & Another Appeal [2024] 4 MLRA 623]

JUDGMENT

Ahmad Terrirudin Mohd Salleh FCJ:

A. Introduction

[1] These appeals raise novel points of law concerning the Malaysian position on the common law restitutionary doctrine of total failure of consideration in light of this Court's prior rulings in Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd [2009] 3 MLRA 1 and Damansara Realty Bhd v. Bungsar Hill Holdings Sdn Bhd & Anor [2012] 1 MLRA 311. These rulings have since been frequently applied by the lower courts and have garnered considerable attention from both legal scholars and practitioners. Much judicial and academic ink has been spilt analysing the legal developments introduced by these rulings. In this judgment, parties will be referred to as they were in the High Court.

[2] Through a letter dated 18 December 2024, the Registry of the Federal Court received an application from learned counsel for the Plaintiffs for these appeals to be heard by a panel larger than that which heard the above two (2) cases in light of the Plaintiffs' Leave Questions No 4 and 5. This request was granted.

[3] We heard the appeal on 24 January 2025 and, curia advisari vult, delivered our broad grounds on 8 April 2025, whereupon, having heard both learned counsel and after anxious consideration, we were constrained to allow the appeals. This is the full grounds of our unanimous decision.

[4] The present appeals, in essence, concern the Assignment Agreements involving four (4) vacant parcels of land assigned by the Plaintiffs to the Defendant for a consideration. These lands were acquired through a Sale and Purchase Agreement ("SPA") between the Plaintiffs and a land developer, which itself subsequently became involved in a broader sequence of separate proceedings involving the Plaintiffs, on the one hand, and the Defendant, on the other.

[5] The proceedings between the Plaintiffs and Defendant in the Courts below proceeded on the legality of these contracts as the central issues for judicial determination, and the leave questions framed by the Plaintiffs primarily concerned the parties' rights and liabilities arising from these contractual arrangements.

[6] The Plaintiffs filed Appeal No 23 against the Court of Appeal's dismissal of their appeal and filed Appeal No 22 against the Court of Appeal's decision allowing the Defendant's appeal against the High Court's dismissal of the counterclaim.

B. Background Of Facts

[7] While the facts of these appeals are not entirely straightforward, they remain sufficiently clear for determination owing to the meticulous efforts of learned counsel in their written submissions and the documents within the appeal records. The facts of the appeals are largely uncontentious. For ease of reference, we set out diagrams illustrating the factual narrative and the relevant timeline of events at the end of this part of the judgment.

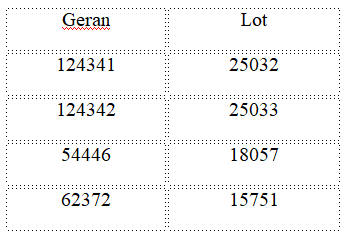

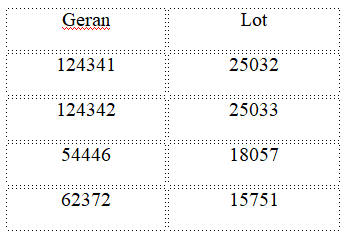

[8] The Plaintiffs entered into an SPA dated 23 June 2015 with DA Land Sdn Bhd ("DA Land") for the purchase of four (4) vacant parcels of land held under (i) Geran 124341 Lot 25032, (ii) Geran 54446 Lot 18057, (iii) Geran 62373 Lot 15751 and (iv) Geran 124342 Lot 25033 all in the District of Gombak, Mukim Rawang, Selangor ("Rawang 4") at the purchase price of RM23,000,000.00. Both parties were aware at the material time that one piece of these lands was under a caveat lodged by one Ho Fook Cheoy ("Ho's caveat"). Under this SPA, it was DA Land's contractual obligation to remove Ho's caveat and to deliver vacant possession free from the encumbrance of Ho's caveat. Section 5 of the Second Schedule of the SPA provides as follows:

"5. PRIVATE CAVEAT/ENCUMBRANCE ON THE SAID PROPERTY

The parties hereto are aware that there is a private caveat lodged by HO FOOK CHEOY (NRIC NO: 6XXX30-07-XXXX) (hereinafter referred to as "the Caveator") vide Presentation No: 44894/2014 on 23 July 2014 (hereinafter referred to as "the said Caveat") against the said Property held under Geran 124342 Lot 25033 Mukim Rawang. The Vendor(s) shall and hereby undertake to cause the said Caveat to be withdrawn or removed within six (6) months from the date hereof falling which provisions of s 4 of this Schedule shall apply without waiting for the expiry of the Cooling-off Period. All monies paid to the Caveator (if any) and all costs and expenses incurred in removing such caveat shall be a debt due by the Vendor(s) to the Purchaser(s)."

[9] Thereafter, the Plaintiffs assigned all their rights and interests in Rawang 4 to the Defendant by way of the Assignment Agreement dated 20 October 2015 for RM25,500,000.00 with the purported knowledge and consent of DA Land. Paragraph 12 of the Recital in the Assignment Agreement provides:

"(12) DA Land has vide a letter dated 2 October 2015 agreed and consented to the assignment by the First Party of all the First Party's rights titles and interest in and to the said Land and under the SPA to the Second Party)."

An undated acknowledgement letter issued by DA Land, bearing the signatures of its Directors and shareholders (the "Chew Brothers"), is relied upon by the Plaintiffs as evidence of DA Land's knowledge of and consent to the said Assignment Agreement. The letter states as follows:

"Re: Sale of the following lands

Mukim Rawang

Vendor: DA Land Sdn Bhd

Purchases: Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong

This is to acknowledge that Mr Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong has on this day paid to Lim Swee Choo and Chiam Eng Huat @ Chiam Eng Hong at our request the sum of Ringgit Twenty Five Million Five Hundred Thousand (RM25,500,000.00) only which is deemed to be and taken by us as part payment towards the purchase by him from us of the above Lands."

[10] Through the Assignment Agreement and an undated Supplemental Assignment Agreement, this RM25,500,000.00 is to be settled as follows:

(a) A sum of RM20,000,000.00 from the purchase price paid by the Plaintiffs to DA Land shall be set-off against the 1st Plaintiff's debt owing to the Defendant;

(b) The balance sum of RM3,000,000.00 shall be paid directly to the Plaintiffs; and

(c) The balance sum of RM2,500,000.00 shall be treated as the Plaintiffs' investment in Rawang 4 representing 4.5% of the value of the lands.

The following contract clauses and a letter dated 2 October 2015, respectively, reflect the above payment arrangements:

(a) Sub-paragraph 10(a) of the Recital in the Assignment Agreement provides as follows:

"By an agreement in writing dated 2 October 2015 made between one of the First Party Lim Swee Choo (F) (NRIC No: 6XXXX3-XX-XXXX) and also acting on behalf of the other First Party Chiam Eng Huat @ Chiam Eng Hong (NRIC No: 4XXXX7-XX-XXXX) of the one part and the Second Party of the other part, the Second Party has agreed to pay to Lim Swee Choo and also acting on behalf of Chiam Eng Huat @ Chiam Eng Hong the new Purchase Price RM25,500,000.00 in the manner as follows:

(a) by way of set-off/contra with Lim Swee Choo (F) (NRIC No: 6XXXX3-XX-XXXX) of the debts amounting to Ringgit Malaysia Twenty Million (RM20,000,000.00) only due and owing from Lim Swee Choo (F) to the Second Party inclusive of the debts under two (2) Agreement dated 29 September 2013 and 31 October 2013 respectively

(b) In so far as relevant, a letter dated 2 October 2015 issued by the 1st Plaintiff to the Defendant provides as follows:

"To,

Mr Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong

I, Lim Swee Choo (NRIC No 6XXXX3-XX-XXXX) acknowledge as follows:

1. Contra with you the sum of Ringgit Twenty Million (RM20,000,000.00) (being the amount presently owed by me to you) for the same amount of RM20,000,000.00 which I and Mr Chiam Eng Huat @ Chiam Eng Hong had paid to DA Land Sdn.Bhd. for purchase of 4 pieces of lands held under Geran 124341-2, 54446 and 62372 for lots 25032-3, 18057 and 15751 respectively in the Mukim of Rawang (said Lands).

2. Receiving from you the following cheques:

UOB 299516 for RM3,000,000.00

RHB 000073 for RM2,500,000,00

RM5,500,000,00

both dated 2 October 2015

being the balance of the amount which I and Mr Chiam Eng Huat @ Chiam Eng Hong had paid to DA Land Sdn Bhd for purchase of the said Lands.

3. The above total sum of RM25,500,000.00 fully settle our proposed purchase of the said Lands from DA Land Sdn Bhd and the agreement thereon shall hereby be deemed to be released and mutually terminated.

..."

(c) Paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Supplemental Assignment Agreement provide as follows:

"2. The parties hereto hereby expressly agree that the Second Party need not deposit the said Security Sum with the Second Party's Solicitors as stakeholders instead it is mutually agreed that the said Security Sum shall be dealt with in the following manner:

2.1 the Second Party shall release part of the said Security Sum amounting to Ringgit Malaysia Three Million (RM3,000,000.00) only directly to the First Party upon the execution of this Agreement;

2.2 the balance of the said Security Sum amounting to Ringgit Malaysia Two Million and Five Hundred Thousand (RM2,500,000.00) only shall be treated as the First Party's investment in the said Land upon the successful completion of the registration of the transfer of the said Land in favour of the Second Party.

3. It is also mutually agreed that the said sum of Ringgit Malaysia Two Million and Five Hundred Thousand (RM2,500,000.00) only shall represent 4.5% of the value of the said Land."

[11] In total, the Defendant had paid RM23,000,000.00 to the Plaintiffs. Under the Assignment Agreement, the Plaintiffs also assigned their rights, title, and interest under the SPA dated 23 June 2015 to the Defendant, including the RM23,000,000.00 they had paid to DA Land under that SPA. Clause 1 of the Assignment Agreement provides as follows:

"1. In consideration of the new Purchase Price of Ringgit Malaysia Twenty - Five Million and Five Hundred Thousand (RM25,500,000.00) only paid by the Second Party, the receipt of which the First Party expressly acknowledged and in further consideration of the Second Party agreeing to be bound by the terms and conditions of the SPA and the provisions herein contained, the First Party HEREBY ASSIGNS ABSOLUTELY UNTO to the Second Party and the Second Party hereby accepts all the rights title and interest of the First Party in the said Land and to the SPA and the full benefits granted thereby and stipulations contained therein and all remedies for enforcing the same."

[12] Parties also agreed that Rawang 4 shall be transferred directly from DA Land to the Defendant. Clause 2 of the Assignment Agreement provides as follows:

"2. Upon the execution of this Agreement, the First Party shall forthwith nominate the Second Party as the transferee of the said Land and shall ensure that the Second Party shall be entitled to execute the relevant Memorandums of Transfer as the transferee of the said Land without any objections or obstruction from DA Land or any third party."

[13] Clause 3 of the Assignment Agreement, in turn, spells out the Plaintiffs' obligation to the Defendant in relation to any caveat on Rawang 4 as follows:

"The First Party shall, simultaneously with the execution hereof, do all acts and things and to execute or cause to be executed all the relevant documents and instruments to transfer the said Land together with all the rights and benefits under the SPA to the Second Party free from any claims, caveats, charges and/or encumbrances and deposit the same with the Second Party's Solicitors as stakeholders."

[14] Further, the Plaintiffs' SPA with DA Land dated 23 June 2015 is referred to in the Assignment Agreement. Clause 4A of the Assignment Agreement provides as follows:

"4A. Simultaneously with the execution of this Agreement, the First Party shall deposit with the Second Party's Solicitors as stakeholders the duly stamped and original documents as follows:

(1) Sale and Purchase Agreement dated 23 June 2015;

(2) 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Supplemental Agreement;

(3) Agreement dated 2 October 2015;

(4) DA Land's letter dated 2 October 2015;

..."

[15] Following a dispute between the Plaintiffs and DA Land which led to the Kuala Lumpur High Court Suit No 22NCVC-688-12/2015 ("Suit 688") involving DA Land and six (6) others against the Plaintiffs and two (2) others, a consent judgment dated 2 June 2016 (based on the Settlement Agreement dated 9 May 2015) was entered, whereupon, inter alia, the Plaintiffs admitted, under para 3(ii)(a), that the Plaintiffs had no right, claim or caveatable interest over Rawang 4.

[16] Unbeknownst to the Plaintiffs, the Defendant entered into an SPA with DA Land on 24 May 2016, which was backdated to 1 October 2015, for the repurchase of three (3) lots of Rawang 4, excluding the one with Ho's caveat, for RM84,000,000.00 (Rawang 3). The consideration of RM25,500,000.00 paid under the Assignment Agreement to the Plaintiffs (of which a total sum of RM23,000,000.00 was paid directly by the Plaintiffs to DA Land under the Plaintiffs' SPA with DA Land dated 23 June 2015) was declared as the deposit to DA Land. The Defendant relies on an undated acknowledgement letter issued by DA Land and signed by the Chew Brothers, which states as follows:

"Re: Sale of the following lands

Mukim Rawang

Vendor: DA Land Sdn Bhd

Purchases: Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong

Price: RM84Million

This is to acknowledge that Mr Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong has on this day paid to Lim Swee Choo and Chiam Eng Huat @ Chiam Eng Hong at our request the sum of Ringgit Twenty Five Million Five Hundred Thousand (RM25,500,000.00) only which is deemed to be and taken by us as part payment towards the purchase by him from us of the above Lands."

[17] By way of a letter dated 28 November 2016, the 1st Plaintiff had, inter alia, demanded that the Defendant pay RM2,500,000.00 due to the alleged Defendant's breach of the Assignment Agreement and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement.

[18] However, a dispute arose between the Defendant and DA Land, culminating in DA Land's Suit No BA-22NCVC-396-07/2017 ("Suit 396") and the Defendant's Suit No. BA-22NCVC-88-02/2017 ("Suit 88") DA Land Sdn Bhd v. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong [2018] 2 MLRH 557, which were heard together in the Shah Alam High Court.

[19] On 2 March 2018, the learned High Court Judge in these suits held, inter alia, that DA Land was entitled to terminate the SPA and forfeit the deposit paid of RM23,000,000.00 as a result of the Defendant's failure to pay the balance of the purchase price of RM61,000,000.00 on or before the completion date, 31 October 2016, and the Defendant had also failed to seek an extension of time for the payment. It was also found that the Defendant admitted to not having paid anything to DA Land and that the Defendant was an unlicensed moneylender. Accordingly, the Court held that the Supplementary Agreements, which form part of the SPA, are sham transactions tainted with illegality and, therefore, void.

[20] In relation to the payment of the deposit, the learned High Court Judge ruled that there was no certainty as to the actual amounts that were allegedly paid by the Defendant to DA Land under the SPA. In the judgment, reported as DA Land Sdn Bhd v. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong [2018] 2 MLRH 557, the learned High Court Judge made the following observation at paras 18, 31, 32, 34, and 35:

"[12]... Testimony Ng Geok Chee (SD1) — Re Examination

S: In 1st Supplementary Agreement p 63 its record that sum of 25.5 million was paid to DA Land. Do you agree?

J: Yes.

S: Did you witness this money go through to your firm accounts?

J: No.

S: According to the agreement, Mr Ong has entitled to proceed to complete the SPA if DA Land does not pay the 61 million, correct? So did he give you instruction to proceed to complete the SPA?

J: No.

S: Did he pay the balance purchase price into your banks account?

J: No.

S: Did you as solicitor ask for an extension of the completion date?

J: No.

From the above testimonies, it is clear to my mind the Defendant/ Purchaser was not ready, able and willing to perform the contract at the time. His solicitor (SD1) had confirm that the balance of RM23 million was not deposited into her firm's account and confirms that she received no instructions from the Defendant/Purchaser to seek an extension or at all and as such she then discharged herself.

[18]... Testimony Ong Koh Hou (SD2) — Cross-Examination

S: In this agreement it is stated that you had paid 25.5 million to the Plaintiff?

J: Correct.

S: Did you make payment through cheque?

J: Some through contra some I helped them to settle off their debt.

S: So you confirmed no actual money was paid?

J: No.

S: So you agree this contra is in relation to the 5 transactions I just referred to you?

J: Yes.

[32] In the above testimonies, the Defendant/Purchaser during cross examination had confirmed that no payments were actually made and that the payment referred to in the Supplementary Agreements 1 and 2 were in fact set offs of various loans owed to him and others.

[34] On the face of these three documents, the illusion created is that the SPA was executed on 1 October 2015 and then subsequently part payment of RM25.5 million was made on 3 November 2015 and another part payment of RM10 million was made on 29 September 2016. Nevertheless from theDefendant/Purchaser's own witness, (SD1), Ng Geok Chee during re-examination, had confirmed that all the three agreements were executed on the same day and that as far as she was aware no actual payment was made. Furthermore, the Defendant/Purchaser has produced no evidence whatsoever to discharge his burden in rebutting the allegation that no monies were paid to DA Land.

Testimony Ng Geok Chee (SD1) — Re-examination

S: Did you witness the giving of the money by way of cheques?

J: No.

S: Did you witness the giving of money by cash?

S: Can I take it that you cannot confirm whether 25.5 million was actually paid?

J: I cannot confirm.

S: Referring to the 2nd Supplemental Agreement, was this 10 million paid into your clients account for you to act as stakeholder and release?

J: No.

S: Did you witness the handing of the cheques for 10 million to DA Land?

J: No.

S: Did you witness the handing of cash to DA Land?

J: No.

S: Although you are solicitor in the SPA, you cannot confirm that 10 million payments was actually made?

J: I can't confirm."

[Emphasis Added]

[21] In relation to the Defendant's involvement as an unlicensed moneylender, the learned High Court Judge observed at para 41 as follows:

"[41]... From the witnesses' testimonies, it is my conclusion that it became clear that the Defendant/Purchaser had developed a mechanism of lending money with property held as security against various third parties, including companies of which Derek and Howard were Directors. The Defendant/ Purchaser had acknowledged that all the transactions took the form of Sale and Purchase Agreement. It also followed that in each instance the Vendor/ Plaintiff was making payments to the Defendant/Purchaser in the form of postdated cheque issued in the Defendant/Purchaser's favour. This highly unusual nature of these transactions failed to be explained by the Defendant when questions were put to him during cross-examination. There are documents bearing the Defendant's signature which clearly state that the transaction listed involve payments of principal sums and their charges of interest. On the issue of post dated cheques, though the Defendant submits that since the cheques were dishonoured, there is no evidence of interest being paid or collected and hence not a moneylender, nevertheless to my mind the Defendant does not explained in any way the nature and purpose of the payments being made via the post dated cheques. The cumulative effect of all the above evidence which remains unchallenged, to my mind the Defendant/ Purchaser is in the business of money lending within the meaning of the Moneylenders Act 1951 cannot be ruled out. That being the case, pursuant to s 5 of the said Act, the Defendant/Purchaser is required to be licensed in order to carry on the business of money lending. No such licence having been tendered in evidence it must be taken that the Defendant/Purchaser is an unlicensed moneylender and that the Supplementary Agreements 1 and 2 are tainted by these illegal activities."

[Emphasis Added]

[22] The Defendant's appeal to the Court of Appeal against the High Court's decision was dismissed on 21 November 2018 (B-02(NCvC)(W)-487-03/2018) Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong v. DA Land Sdn Bhd & Ors [2018] 5 MLRA 648, and the Defendant's further application for leave to appeal against the Court of Appeal's decision was also dismissed by this Court on 22 July 2020 (08(f)-621-12/2018(B)).

[23] On 15 June 2020, the Plaintiffs, inter alia, sought a declaration that the Defendant had breached the Assignment Agreement dated 20 October 2015 and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement, and pursued the balance payment of RM2,500,000.00 as special damages against the Defendant through Kuala Lumpur High Court Civil Suit No: WA-22NCVC-293-06/2020 Lim Swee Choo & Satu Lagi lwn. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong [2022] MLRHU 928 ("the main suit" from which the present appeals originate). This amount is due and owing to the Plaintiffs after the Defendant failed to invest the said amount into Rawang 4. The Defendant, on the other hand, counterclaimed the return of RM23,000,000.00 paid to the Plaintiffs.

C. Antecedent Proceedings And Judgment Below

[24] On 6 August 2021, the parties framed the agreed issues to be tried and submitted them for judicial determination before the High Court as follows:

(a) Whether the SPA dated 23 June 2015 between the Plaintiffs and DA Land for the purchase of Rawang 4 is tainted by illegal moneylending transactions, in contravention of the Moneylenders Act 1951, and thereby void, unlawful, and unenforceable?;

(b) Whether all agreements between the Plaintiffs and the Defendant concerning Rawang 4 are tainted by illegal moneylending transactions originating from the SPA dated 23 June 2015, and are consequently void, unlawful, and unenforceable?;

(c) Whether the Plaintiffs were aware that DA Land had sold one (1) parcel of land from Rawang 4, namely, Geran 124342 Lot 25033, Mukim Rawang, District of Gombak, State of Selangor to Ho Fook Cheoy at the time the Plaintiffs entered into the Assignment Agreement dated 20 October 2015 with the Defendant?;

(d) Whether the Plaintiffs had consented to the Defendant entering into a new SPA dated 1 October 2015 (which was in fact signed on 24 May 2016) with DA Land?;

(e) Whether the Defendant has breached the Letter dated 2 October 2015, the Agreement dated 20 October 2015 and the Supplemental Agreement?;

(f) Whether the Plaintiffs have suffered losses amounting to RM2,500,000.00 and are entitled to the reliefs claimed?; and

(g) Whether the Defendant has suffered losses amounting to RM23,000,000.00 and is entitled to the reliefs claimed?

[25] The nature of the Plaintiffs' claim is that the Defendant had entered into an SPA dated 1 October 2015 with DA Land, executed on 24 May 2016, to purchase Rawang 3 for RM84,000,000.00 without the Plaintiffs' knowledge in breach of the letter dated 2 October 2015, Assignment Agreement and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement. As a result of this breach, the Plaintiffs' investment of RM2,500,000.00 in Rawang 4 was diminished, causing them to suffer a corresponding loss.

[26] On the other hand, the main plank of the Defendant's case is that the Plaintiffs had deceived him into entering the Assignment Agreement dated 20 October 2015. He contended that the Plaintiffs had failed to disclose that DA Land had, by an SPA dated 22 July 2014, sold one parcel of Rawang 4 (Lot 25033, Title No 124342) to Mr Ho Fook Cheoy prior to the Assignment Agreement. Upon being confronted with this transaction, the Plaintiffs had allegedly expressed regret for having concealed the information from the Defendant. With the consent of both the Plaintiffs and DA Land, and following the Defendant's suspicion that the Plaintiffs' SPA with DA Land was a questionable transaction, the Defendant was constrained to sever his transaction from that of the Plaintiffs and independently enter into an SPA dated 1 October 2015, signed on 24 May 2016, with DA Land for the purchase of Rawang 3.

[27] According to the Defendant, the Plaintiffs' SPA with DA Land was tainted with illegality as it constituted an illegal moneylending transaction with Rawang 4 used as collateral for an unlawful loan of RM20,000,000.00 between them. It followed that the Plaintiffs had no legal power to assign any right in the Plaintiffs' SPA to the Defendant from the outset, in view of the Plaintiffs' SPAbeing illegal. The Assignment Agreement and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement, which were the products of the illegal moneylending transaction, were therefore equally illegal and void.

[28] The trial proceeded on 20 September 2021, 21 September 2021, 23 September 2021, and 24 September 2021. The matter was then adjourned, and the parties' clarification took place on 20 December 2021 and 15 February 2022. On 18 February 2022, the learned High Court Judge dismissed the Plaintiffs' claim and the Defendant's counterclaim without any order as to costs. In essence, the main findings of the learned High Court Judge may be summarised as follows:

(a) There was no evidence to support the Defendant's allegation that the Assignment Agreement between the Plaintiffs and the Defendant was tainted by illegal moneylending transactions between the Plaintiffs and DA Land. The burden of proving the allegation lies with the Defendant and that the Defendant's failure to call the material witnesses (ie, the Chew Brothers) to testify on the allegation of unlicensed moneylending activities was detrimental to the Defendant's case on the point. Accordingly, there is no basis for the Court to hold that the Assignment Agreement is void or unlawful;

(b) The SPA between the Plaintiffs and DA Land contains a provision stating that there is a caveat over one (1) parcel of land from Rawang 4. This indicates that the Plaintiffs were aware of the existence of the caveat filed by Mr Ho Fook Cheoy. A perusal of the caveat clearly shows that the caveator had purchased the said land. Therefore, the Plaintiffs had knowledge that DA Land had sold the land to the caveator;

(c) In view of the sale, the Assignment Agreement could not be completed without amendment. It is, therefore, unreasonable for PW1 (ie, the 1st Plaintiff) to maintain that she had no knowledge whatsoever of the new SPA between the Defendant and DA Land.The Defendant did not breach the Assignment Agreement or the Supplemental Assignment Agreement. It must be noted that the obligation to remove Ho's caveat rested not with the Defendant but with DA Land;

(d) Although the Plaintiffs have suffered a loss, the Defendant did not breach the Assignment Agreement or the Supplemental Agreement. Following the principles in Berjaya Times Square and Damansara Realty on total failure of consideration, it is unreasonable for the Plaintiffs to pursue their claim against the Defendant for the sum of RM2,500,000.00 given that the Defendant was no longer able to acquire the entirety of Rawang 4;

(e) Having concluded the SPA for Rawang 3 with DA Land, the Defendant did not claim for the return of RM23,000,000.00 from the Plaintiffs on the ground that the Assignment Agreement was tainted with the alleged illegal moneylending transactions.The Defendant had taken no action against the Plaintiffs when the agreements involving Rawang 4 and Rawang 3 failed to materialise. It was only when the Plaintiffs filed the main suit that the Defendant filed his counterclaim for his alleged loss. The Defendant's loss was not caused by the Plaintiffs but rather by the Defendant's own greed.

[29] Aggrieved by the decision of the learned High Court Judge, the Plaintiffs and the Defendant filed their respective appeal to the Court of Appeal in Civil Appeal No W-02(NCVC)(W)-439-03/2022 ("Appeal No 439") and Civil Appeal No. W-02(NCVC)(W)-449-03/2022 ("Appeal No 449"), Lim Swee Choo & Anor v. Ong Koh Hou @ Won Kok Fong & Another Appeal [2024] 4 MLRA 623, respectively. On 24 July 2023, the Court of Appeal dismissed the Plaintiffs' Appeal 439 with costs and allowed the Defendant's Appeal 449 with costs. The main findings of the learned panel of the Court of Appeal may be summarised as follows:

(a) The Defendant bears the evidential burden to prove illegality under s 103 of the Evidence Act 1950 [Act 56]. The Assignment Agreement and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement had not been tainted with the Plaintiffs' SPA as no evidence had been adduced at the trial to prove, on a balance of probabilities, that the said SPA had contravened the Moneylenders Act 1951 [Act 400]. Even if it is assumed that the said SPA had breached Act 400, no evidence has been adduced to show that its illegality subsequently tainted the Assignment Agreement and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement. Therefore, there is no room for the Defendant to invoke s 66 of the Contracts Act 1950 [Act 136];

(b) Citing Berjaya Times Square and Damansara Realty, the Court of Appeal ruled that there was a total failure of consideration as the Defendant had paid RM23,000,000.00 to the Plaintiffs and that following Suit 688, the Plaintiffs had no right, claim or caveatable interest in Rawang 4 and were not in a position to absolutely assign any right or interest therein to the Defendant under the Assignment Agreement and Supplemental Assignment Agreement. The Plaintiffs had actual knowledge of the sale of one (1) parcel of land from Rawang 4 to Mr Ho Fook Cheoy and they have not demonstrated that the High Court's finding of fact regarding their knowledge is plainly wrong;

(c) In view of the total failure of consideration, the Plaintiffs' Appeal No. 439 regarding the amount of RM2,500,000.00 should be dismissed, not because there was no breach by the Defendant but because allowing the Plaintiffs to claim the amount from the Defendant would be unconscionable and result in their unjust enrichment. The Court of Appeal disagreed with the learned High Court Judge's factual finding that the Plaintiffs had suffered a loss as the Plaintiffs in the first place could not, in fact, absolutely assign any right or interest in Rawang 4;

(d) The total failure of consideration also justified allowing the Defendant's Appeal No 449. The Court of Appeal held that the learned High Court Judge should have applied the restitutionary principle and ordered the Plaintiffs to return RM23,000,000.00 to the Defendant, irrespective of the Defendant's greed or altruism or the Defendant's failure to deny the 1st Plaintiff's letter of demand dated 28 November 2016, as the Defendant would have otherwise paid the sum in vain resulting in an injustice to the Defendant and an unjustifiable windfall to the Plaintiffs. Notwithstanding their actual knowledge of the sale to Mr Ho Fook Cheoy, the Plaintiffs entered into the Assignment Agreement and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement with the Defendant without disclosing the said sale and received RM3,000,000.00 from the Defendant. By reason of their inequitable conduct, the Plaintiffs cannot now rely on the doctrine of equitable estoppel;

(e) Section 71 of the Contracts Act 1950 [Act 136] only applies where there is no contract between the parties. In the present case, the Plaintiffs and Defendant had concluded the Assignment Agreement and the Supplemental Assignment Agreement.

[30] Both rulings, read together, support the following conclusions:

(a) It is the concurrent finding of the learned High Court Judge and the learned panel of the Court of Appeal that the Plaintiffs' SPA with DA Land dated 23 June 2015 is valid, as are the Assignment Agreement dated 20 October 2015 and the undated Supplemental Assignment Agreement, both entered into between the Plaintiffs and the Defendant;

(b) Both the High Court and the Court of Appeal referred to Berjaya Times Square and Damansara Realty in support of their findings that there was a total failure of consideration thereby justifying the dismissal of the Plaintiffs' claim against the Defendant.

D. Leave Questions

[31] During the application for leave to appeal to this Court, the Plaintiffs were the Applicants and the Defendant was the Respondent. Their respective capacity was mirrored in the leave question. On 3 July 2024, the Plaintiffs were granted leave to appeal to this Court on the following questions of law:

(a) QUESTION 1: Whether the doctrine of a total failure of consideration, as an equitable doctrine, could be invoked by the Respondent to recover from the Applicants a sum of RM23,000,000.00 which sum had previously been declared by the High Court in a related suit (affirmed on appeal) as non-recoverable because it comprised part of an illegal moneylending transaction engaged in by the Respondent and in which proceedings the Respondent was declared as an unlicensed moneylender?

(b) QUESTION 2: Whether the doctrine of a total failure of consideration, as an equitable doctrine, could be invoked by the Respondent to recover a sum of RM23,000,000.00 from the Applicants when the Respondent was held by the High Court in the present case as the party who had caused the loss and on which "loss" he had based his claim of a total failure of consideration?

(c) QUESTION 3: Whether the doctrine of a total failure of consideration could apply where there has been performance or part-performance of the contract, which in this case was the assignment of a sale agreement by the Applicants to the Respondent, pursuant to which the Respondent made part- payment thereof and received the benefit of the assignment?

(d) QUESTION 4: Whether the true test of a total failure of consideration is as stated by the House of Lords in Stocznia Gdanska SA v. Latvian Shipping Co [1998] 1 WLR 574 per Lord Goff of "whether the promisor has performed any part of the contractual duties in respect of which payment is due" and not the test of "whether the party in default has failed to perform his promise in its entirety" as stipulated by the Federal Court in Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd [2009] 3 MLRA 1, (at para 18)?

(e) QUESTION 5: Whether the case of Berjaya Times Square, supra, relied on by the Court of Appeal has wrongfully conflated the right of rescission of a contract with the right to seek restitution of monies paid and received (which is independent of rescission or termination of a contract) and is, therefore, not truly classifiable as an authority for the doctrine of restitution based on a total failure of consideration?

(f) QUESTION 6: Whether on its true principle the doctrine of a total failure of consideration has no application where there has been only a partial failure of performance or the claimant has derived some benefit from the contract so that he is restricted to an action in damages for breach of contract as opposed to restitution per Phang Quee v. Virutthasalam & Ors [1965] 1 MLRA 304 and Baltic Shipping Co v. Dillon [1993] 111 ALR 289?

For the purposes of the present appeals, references to the parties in these questions will be modified to reflect their respective capacities as they appeared in the proceedings before the High Court.

E. Our Analysis And Decision

(i) Academic Literature In Judicial Reasoning

[32] The judicial decision-making process entails a critical engagement with live and intelligent legal controversy presented in the courtroom. This process, within which the systematic analysis of fact and law is integral to judicial reasoning, constitutes a discipline in its own right. The integrity of this discipline is preserved when judges remain meticulous in their strict adherence to established methodological approaches in interpreting and applying the law, even if their findings and decisions are later reversed on appeal or review. Quoting Lord Reid, Lord Mance, in His Lordship's speech titled "The Role of Judges in a Representative Democracy" during the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council's Fourth Sitting in The Bahamas on 24 February 2017, reiterated:

"[Judges] will consider the implications of [a] decision, and will ensure that it is consistent with the general purpose and scheme of the law or principle... Judging is thus not a science, but a discipline. The good judge is loyal to well established approaches and methods of reasoning. But she or he may in the last analysis have to exercise an important judgment as to the relevant weight of different and sometimes competing considerations, in deciding in which sense to state or restate the legal position."

[Emphasis Added]

[33] Within the constraints of our duty to method of reasoning, coherence, rationality and fidelity to legal principles and rules, it must be acknowledged that the scholarly contributions of passionate legal academics, serving judges writing in an extra-judicial capacity, legal practitioners, and even retired judges are indispensable to lucid judicial reasoning. In the present appeal, for instance, learned counsel for the Plaintiffs referred us to the following academic commentaries on Berjaya Times Square and Damansara Realty to which we shall turn at great length in the ensuing part of this judgment:

(a) Visu Sinnadurai. [2023]. Law of Contract(5th Edn), LexisNexis, Vol 2, at pp 1161-1165;

(b) David Fung Yin Kee. [2019]. Berjaya Times Square Revisited: What's in a Name?, Journal of the Malaysian Judiciary at pp 169-203;

(c) Low Weng Tchung. [2015]. The Law of Restitution and Unjust Enrichment in Malaysia, LexisNexis at pp 61, 430, 465-468; and

(d) Visu Sinnadurai. [2011]. Law of Contract (4th Edn), LexisNexis at pp 1031-1042.

[34] Additionally, by judicial notice, we also extended our reference to the following works which reflect a similar academic perspective:

(a) Cheong May Fong & Lee Yin Harn. [2016]. Civil Remedies (2nd Edn), Sweet & Maxwell, at pp 36-39;

(b) J W Carter. [2011]. Fundamental Breach and Discharge for Breach under the Contract Act 1950 (Malaysia), Journal of Contract Law, Vol 28, at pp 85-100.

For reasons that will become apparent, these academic works highlight several critical points which, in our considered view, the learned panels in Berjaya Times Square and Damansara Realty might have found beneficial had these points been brought to their attention at the time of deciding those appeals. It would be remiss of us to disregard these points now that the opportunity to consider them is before us.

[35] Given the far-reaching effect of appellate judicial rulings as precedents, judicial reasoning that detaches or that fails to engage with, in appropriate instances, informed critique duly submitted by the parties not only weakens the resulting judgment but also undermines its persuasive legitimacy. Respectful and fair criticism of judicial precedents objectively presented in published academic commentaries not only signifies judicial transparency and a commitment to fostering legal literacy and discourse but also plays a vital role in refining our home-grown jurisprudence and promoting the continual development of, in the context of the present appeal, a corpus of contract law.

[36] In the discharge of our judicial role, we must refrain from interpreting laws according to our own standards or ideas of reason and justice. What matters is not what we believe to be right but rather what we may reasonably believe that some other man of normal intellect and conscience might reasonably look upon as right. The standard is, therefore, an objective one.

[37] As we have seen within the common law tradition, Lord Mance of Frognal, in His Lordship's extra-judicial speech titled "The Changing Role of an Independent Judiciary", delivered during the Twenty-Third Sultan Azlan Shah Law Lecture on 15 December 2009 and published in Sultan Azlan Shah Law Lectures II — Rule of Law, Written Constitutions & The Common Law Tradition, [2011], Sweet & Maxwell, acknowledged the following at p 387:

"In contrast, common law judges have carefully to place each decision in the context of prior case law and the submissions before him. In this way, the common law judge aims to legitimise his or her decisions and to ensure their social acceptability. The common law's traditional invocation of the reasonable person fits into the same pattern. The common law judge is appealing to the ordinary member of the public."

[Emphasis Added]

Therefore, we find it imperative to act on learned counsel for the Plaintiffs' invitation to consider these academic works which, in our considered view, are beneficial in enabling an objective examination of the precedents under review closer to the above ideal. Ultimately, however, the duty for deciding these appeals rests with us.

[38] Some academic works are directed at judges, suggesting perspectives on how our Courts should decide cases coming before us. Observing how legal academics have engaged with novel or contentious legal issues, whether in the abstract or in response to decided cases, may better equip us to address such matters in the course of judicial determination. In this context, the relationship between our Courts and our legal scholars is dialogic. For instance, Visu Sinnadurai [2011], in his work, stated at p 1042 as follows:

"In conclusion it is submitted that the doctrine of total failure of consideration generally has no place in the area of breach of contract. It has limited application only in cases where the action is based on restitutionary relief, ie, where an innocent party seeks recovery of monies paid and not in for a claim in damages for breach. In all other cases of breach, the traditional test as employed by Malaysian and English cases, ie, 'fundamental breach, or the like, is the correct approach. Total failure of consideration certainly has no place in cases dealing with time such as in Berjaya Times Square. It is hoped that the opportunity will soon arise for the Federal Court to revisit its decision in Berjaya Times Square and restate the correct position of the law. Uncertainties in the law cause discomfort to businessmen and lawyers alike."

[Emphasis Added]

[39] It goes without saying that academic commentaries cannot trump primary sources of law. However, the value of the lifelong academic contributions of legal experts in the field, particularly those whose scholarship has shaped comparative and fundamental theoretical understanding, form a body of work that Courts would do well to consider in the pursuit of responsible judicial reasoning. Equally important are the academic insights of derivative contributors, which also carry force in the dynamic progression of legal thought. In essence, no principled approach to judicial adjudication can disregard the contributions of academic literature.

[40] That being said, we did not, however, regard our approach to the above matter as an innovation. In fact, Lord Denning MR in White v. Blackmore [1972] 3 All ER 158 (CA) expressed disappointment with counsel for failing to cite relevant academic literature in their submissions when stating at p 167 as follows:

"Ashdown v. Williams has been vigorously criticised by Professor Gower in the Modern Law Review. He pointed out the consequences of it, if carried to its full length. He gave good reasons for thinking that a licensor could not exempt himself from liability to his licensee except by contract. Unfortunately, his criticisms were not brought to our attention. I am disposed to agree with them."

[Emphasis Added]

[41] Illustrative of the essence of our point, Steyn LJ delivering the supporting judgment of the English Court of Appeal in White v. Jones [1993] 3 All ER 481 (CA) made the following extensive observation at p 500:

"It is therefore not altogether surprising that the appeal in the present case lasted three days, and that we were referred to about forty decisions of English and foreign courts. Pages and pages were read from some of the judgments. But we were not referred to a single piece of academic writing on Ross v. Caunters. Counsel are not to blame: traditionally counsel make very little use of academic materials other than standard textbooks. In a difficult case it is helpful to consider academic comment on the point. Often such writings examine the history of the problem, the framework into which a decision must fit and countervailing policy considerations in greater depth than is usually possible in judgments prepared by judges who are faced with a remorseless treadmill of cases that cannot wait. And it is arguments that influence decisions rather than the reading of pages upon pages from judgments. I am not suggesting that to the already extremely lengthy appellate process there should be added the reading of lengthy passages from textbooks and articles. But such material, properly used, can sometimes help to give one a better insight into the substantive arguments. I acknowledge that in preparing this short judgment the arguments for and against the ruling in Ross v. Caunters were clarified for me by academic writings."

[Emphasis Added]

[42] In the context of contract law, which is directly relevant to the present appeal, Lord Browne-Wilkinson in his speech in the House of Lords in Linden Gardens Trust Ltd v. Lenesta Sludge Disposals Ltd [1994] AC 85 (HL) stated the following at p 112:

"There is therefore much to be said for drawing a distinction between cases where the ownership of goods or property is relevant to prove that the plaintiff has suffered loss through the breach of a contract other than a contract to supply those goods or property and the measure of damages in a supply contract where the contractual obligation itself requires the provision of those goods or services. I am reluctant to express a concluded view on this point since it may have profound effects on commercial contracts which effects were not fully explored in argument. In my view the point merits exposure to academic consideration before it is decided by this House."

[Emphasis Added]

[43] However, we are mindful of the danger of citing academic literature that merely expresses opinions or preferences unsupported by legal analysis, as it provides little assistance and does not advance our reasoning. According weight to such writings solely because they are academic in origin is a misconceived approach. Lord Goff in Hunter v. Canary Wharf Ltd [1997] 2 WLR 684 (HL) at p 694 articulated:

"I would not wish it to be thought that I myself have not consulted the relevant academic writings. I have, of course, done so as is my usual practice; and it is my practice to refer to those which I have found to be of assistance, but not to refer, critically or otherwise, to those which are not. In the present circumstances, however, I feel driven to say that I found in the academic works which I consulted little more than an assertion of the desirability of extending the right of recovery in the manner favoured by the Court of Appeal in the present case. I have to say (though I say it in no spirit of criticism, because I know full well the limits within which writers of textbooks on major subjects must work) that I have found no analysis of the problem; and in circumstances such as this, a crumb of analysis is worth a loaf of opinion. Some writers have uncritically commended the decision of the Court of Appeal in Khorasandjian v. Bush [1993] Q.B. 727, without reference to the misunderstanding in Motherwell v. Motherwell, 73 D.L.R. (3d) 62, on which the Court of Appeal relied, or consideration of the undesirability of making a fundamental change to the tort of private nuisance to provide a partial remedy in cases of individual harassment. For these and other reasons, I did not, with all respect, find the stream of academic authority referred to by my noble and learned friend to be of assistance in the present case."

[Emphasis Added]

(ii) Certainty In Judicial Interpretation And The Rule Of Law

[44] Central to the above understanding is consideration of legal certainty and predictability, traceable to relevant interpretation methods used by Judges to reach a proper conclusion in judicial adjudication, as important components of the Rule of Law. Certainty and predictability in judicial decisions presuppose that legal principles and rules must not only be clear but also interpreted and applied faithfully and correctly by the Courts.

[45] Legal methods then serve to ensure rational reasoning and, even in cases involving novel legal issues, enable the Court to adopt a variety of rationally predictable methods in judicial decision-making, thereby promoting legal certainty on the broadest possible scale. By positioning the Rule of Law as the ultimate objective, achievable through legal certainty which, in turn, is underpinned by legal methods, the scope for judicial discretion may be preserved without allowing it to devolve into arbitrariness. In relation to the present appeals before us, we find it imperative to revisit two important legal methods: (i) statutory interpretation and (ii) judicial precedent.

[46] As the commonly used legal method in judicial adjudication where legal principles are applied to facts guided by judicial syllogisms, legal certainty requires the Court to interpret statutory provisions based on certain predetermined approaches of statutory interpretation (some referred to them as theories or arguments) and their priority, which can be categorised as follows:

(a) The textual interpretation requires the Court to give due regard to the plain and ordinary meaning of the words used in the statutory provision under review (Tebin Mostapa v. Hulba-Danyal Balia & Anor [2020] 4 MLRA 394, United Hokkien Cemetries Penang v. The Board Majlis Perbandaran Pulau Pinang [1979] 1 MLRA 95, and Foo Loke Ying & Anor v. Television Broadcasts Ltd & Ors [1985] 1 MLRA 635. Only if the natural construction of the words fails to answer the question before the Court is the Court then compelled to look beyond the strict letter of the legislation to discern its purpose. By focusing on the objective meaning of the text independent of any ideological or political-moral context, this approach limits judicial discretion in the interpretative process thereby promoting a very high degree of certainty and predictability in judicial outcomes;

(b) The intentionalist approach to statutory interpretation requires the Court to give due regard to, without doing actual violence to the clear meaning of any of the words used, the underlying intention of Parliament and to interpret the words used in the manner Parliament intended them to be understood (Ng Hoe Keong & Ors v. OAG Engineering Sdn Bhd & Ors [2022] 4 MLRA 535, Letitia Bosman v. PP & Other Appeals [2020] 5 MLRA 636, Chor Phaik Har v. Farlim Properties Sdn Bhd [1994] 1 MLRA 356, Marley v. Rawlings [2012] EWCA Civ 61 (CA); Beswick v. Beswick [1968] AC 58 (HL); and Black-Clawson International Ltd v. Papierwerke Waldhof-Aschaffenburg AG [1975]AC 591 (HL)). Since all statutes are the product of deliberate legislative action, each represents the collective will of the society as expressed through its democratically elected representatives. Legal certainty is upheld when the Court interprets a provision in accordance with its legislative purpose, relying on sources such as Hansard and historical materials which are publicly accessible thereby honouring the democratic legitimacy and justification of the provision rather than substituting the judge's personal will;

(c) The systematic approach to interpretation (within which harmonious interpretation forms a core aspect and may be supplemented by comparative analysis) requires the Court toconstrue the words used in a particular provision in a manner most compatible with the other components of the same statute and the wider legal system (Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai & Anor v. Muziadi Mukhtar [2019] 6 MLRA 307, and Mahiaddin Md Yasin v. PP [2024] 6 MLRA 914. This approach promotes consistency and coherence throughout the legal system thereby ensuring legal certainty and predictability. Therefore, alternative interpretations that conflict with legal principles or result in logical inconsistencies are unsustainable.

(d) Lastly, teleological interpretation requires the Court to adopt a reading that gives effect to the underlying goals of the provision under review by referring to its broad purposes or foundational values (Asian International Arbitration Centre v. One Amerin Residence Sdn Bhd & Ors And Another Appeal [2025] 3 MLRA 83. R (On The Application Of Quintavalle) v. Secretary Of State For Health [2003] 2 All ER 113 (HL); James Buchanan & Co Ltd v. Babco Forwarding And Shipping (UK) Ltd [1977] 1 All ER 518 (CA)). Commonly referred to as purposive interpretation, this approach is more expansive than the intentionalist approach, as it goes beyond identifying the specific intent of Parliament and instead focuses on the broader objectives, logical theory and rationale of the law. However, this approach cannot be viewed in isolation as a mere pursuit of subjective ideals at the fancy of the Court or solely as a form of consequentialism. Rather, it must be grounded in other established factors within the legal system. The more adequately these supporting factors (including natural justice, human rights, policy considerations, empirical consequences and practical viability to substantiate the meaning of the words used) are addressed, the more robust the reasoning becomes. This is because the interpretative exercise does not only consider the goal of the single provision but also the optimal functioning of the legal system as a whole which implies a certain predictability and certainty in judicial outcomes.

[47] Where multiple approaches are applicable, how should the Courts determine which approach to adopt? It may well be argued that the aforementioned approaches are independent and that no definitive hierarchy can be established, as each approach reflects a distinct underlying value, and their relative importance is perceived differently by different individuals. While these separate approaches may complement one another in ideal circumstances, such harmony is not always achievable in practice, given the divergence in reasoning behind interpretative perspectives, the context of the case, and judicial decisions. Therefore, some form of sequential primacy is necessary to ensure legal certainty.

[48] Unless compelling reasons justify a departure, these approaches may be ranked in the conventional order; in our considered view, the spectrum from textual, intentionalist, and systematic to teleological approaches reveals a demonstrable weakening of legal certainty corresponding with an increasing tendency towards judicial discretion in statutory interpretation. Quite recently, Lord Sales, in his address titled "Statutory Interpretation in Theory and Practice", delivered to the Office of Parliamentary Counsel on 20 March 2025, articulated the following at p 16:

"Citizens subject to the law expect the legislator to legislate for a coherent, not an arbitrary regime. So they expect the courts to interpret statutes to produce coherent results."

[Emphasis Added]

[49] As rudimentary as the above discussion may appear, we will see that what may be regarded as a judicial development in Berjaya Times Square reveals how this Court interpreted s 40 of the Contracts Act 1950 [Act 136] within the framework of the law of restitution through a curious exercise that departs from conventional reasoning approach which typically derives conclusions through step-by-step formal methodology and doctrinal justification as illustrated above even though, on its fact, the decision in Berjaya Times Square was correctly made. With all due respect, in our considered view, methodological randomness will undermine legal certainty and the basis of the Rule of Law. We will then see how Berjaya Times Square fared in relation to the academic literature cited by the learned counsel for the Plaintiffs.

[50] This, however, does not mean that Courts cannot develop legal solutions through judicial creativity. As we alluded to above, what matters is not what we believe to be right but rather what we may reasonably believe another person of normal intellect and conscience might reasonably regard as right. This speaks volumes about the tension between authoritative reasoning (which relies on legal authorities) and substantive reasoning (which incorporates fairness, public interest, economic and moral considerations) in the judicial decision-making process. The former produces decisions in accordance with the law while the latter seeks justice in individual cases (provided that substantive reasoning remains within the framework of recognised sources of law). When both are harmonised, the resulting decisions are legally sound and reasonable.

[51] However, when the goals of the two (2) approaches conflict, the outcome may be either legal but unreasonable or reasonable but not in accordance with the law. In the larger scheme of things, this reflects the struggle between legal certainty (decisions made according to established law) and what is regarded as "correct" (ie, reasonable). In the context of judicial development in the pursuit of justice in individual cases, considerations of correctness often take precedence over certainty. But should justice in an individual case always prevail over adjudication in accordance with the law? Cumming-Bruce LJ in Davis v. Johnson [1978] 1 All ER 841 (CA) observed at p 880 as follows: