Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Ahmad Zaidi Ibrahim, Collin Lawrence Sequerah, Faizah Jamaludin JJCA

[Civil Appeal Nos: A-04(NCvC)(W)-444-10-2023 & A-04(NCvC)(W)-447-10-2023]

11 September 2025

Tort: Negligence — Road accident — Liability of appellants relating to fatal accident resulting in death of deceased — Loss of dependency — Special damages — Whether respondents had discharged their burden of proving that deceased's death caused by appellants' negligence — Quantum of damages

These two appeals by Projek Lebuhraya Usahasama Berhad ("PLUS") and Projek Penyelenggaraan Lebuhraya Berhad ("PROPEL") challenged the decision of the High Court, which affirmed the Sessions Court's findings on liability relating to a fatal accident at KM177.8 of the Lebuhraya Utara-Selatan ("Highway"), resulting in the death of motorcycle rider, Azizi bin Zakaria ("deceased"). They also contested the High Court's decision allowing the respondents' cross-appeal with regard to quantum. PLUS held the concession for the Highway while PROPEL was its contractor for maintenance and repairs. The respondents, as the parents of the deceased, had brought an action for negligence at the Sessions Court against PLUS, PROPEL, and Muhammed Azmer Jamel ("SD2") for the death of their son. The Sessions Court found both PLUS and PROPEL negligent and had allocated 80% of the liability to them and 20% to the deceased. It awarded the respondents the sum of RM57,600.00 for loss of dependency and the sum of RM3,000.00 as special damages. Upon appeal by PLUS and PROPEL, the High Court Judicial Commissioner ("JC") upheld the decision of the Sessions Court Judge ("SCJ") regarding liability and allowed the respondents' cross-appeal, increasing the quantum of loss of dependency to RM500.00 per month. Hence, the present appeals in which the main issue was whether PLUS and/or PROPEL were liable for the condition of the Highway on the night of the accident. It was not disputed that the accident resulted from the deceased's motorcycle hitting a yellow-orange object on the Highway, and the area was pitch black at the time of the accident. There were no street lights on the stretch of the Highway where the accident occurred. This was confirmed by SD2 and the investigating officer ("SP1"), who had arrived at the site approximately one hour after the accident. The appellants' case was that the JC had erred in law and in fact in upholding the SCJ's finding that the respondents had discharged their burden of proving that the deceased's death was caused by PLUS and PROPEL's negligence, and allocating 80% of the liability to the appellants.

Held (dismissing both appeals by PLUS and PROPEL with costs):

(1) From the facts and circumstances, PLUS owed the deceased a duty of care at common law to maintain the Highway in good repair and condition. This was because: (i) the harm to users of the Highway caused by PLUS or its contractors' failure to maintain the Highway in good repair and condition was reasonably foreseeable; and (ii) there was a proximity of relationship between the Highway users and PLUS. As for what "maintain in good repair and condition" meant, based on Burnside v. Emerson, first, the Highway must be in such a condition as to be dangerous for traffic; secondly, the dangerous condition was due to a failure to maintain, which included a failure to keep it in good repair and condition; and thirdly, if there was a failure to maintain, PLUS would be liable prima facie for any damage resulting therefrom. In order to escape liability, PLUS must prove that it took such care as, in all the circumstances, was reasonable. (paras 33-34)

(2) Both SP1 and SD2 testified that the stretch of the Highway on which the accident occurred was pitch black. One of the dangers to users on the Highway was foreign objects on the road, which might have been left by road users or others, or dropped from vehicles using the Highway. In the instant case, it was a yellow-orange object identified as a wheel chock for trucks and trailers. SP1 testified that he did not see the yellow-orange object when he patrolled the road approximately 20 minutes before the accident. In fact, SP1 said that even when he came back to the site after the accident, he was not able to see the yellow-orange object on the road. When asked by the SCJ why he wrote that the accident was caused by hitting an object on the road, SP1 said it was based on what he was told by the motorcyclists at the accident site. It was observed that in several instances, accidents occurred due to motorists being unable to see obstructions on the Highway at night when the area was unlit. On unlit roads at night, typically only the dividing lines painted with reflective paint or the road reflectors were visible. Therefore, a reasonable course of action in the circumstances would be for PLUS to install street lighting at intervals of, for instance, 300 metres or another distance deemed appropriate, in accordance with established engineering practices. Furthermore, with the introduction of solar-powered street lights, operational expenses were expected to be significantly reduced compared to those associated with conventionally powered lighting systems. In the circumstances, PLUS did not take reasonable steps to maintain and keep the Highway in good repair and condition. (paras 37, 44, 48, 49 & 50)

(3) PLUS argued that its duty to maintain and repair the Highway was delegable based on the decision of the Federal Court in Hemraj & Co Sdn Bhd v. Tenaga Nasional Berhad ("Hemraj v. TNB"). PLUS contended that because it had appointed PROPEL as its independent contractor to maintain and repair the Highway, PLUS was not liable for the damage caused to users of the Highway as a result of its negligence. Lord Sumption in Woodland v. Swimming Teachers Association And Others ("Woodland") explained that the expression "non-delegable duty" had become the conventional way of describing those cases in which the ordinary principle was displaced; the duty extended beyond being careful, to procuring the careful performance of work delegated to others. Work relating to the maintenance and repair of a highway was hazardous due to the number of vehicles that went up and down the highway on a daily basis. On this point alone, based on Woodland and Hemraj v. TNB, PLUS's duty of care to maintain the Highway in good repair and condition was non-delegable. Therefore, although PLUS had delegated its duty to PROPEL, it remained liable for PROPEL's negligence that resulted in damage or injury to the users of the Highway. Accordingly, the Sessions Court was not plainly wrong in its decision as regards its finding of liability and its allocation of liability to the appellants and the deceased, and the High Court was not plainly wrong in upholding the Sessions Court's decision. Hence, there was no basis for appellate intervention in the High Court's determination on liability. (paras 51, 52, 57, 59, 62, 63 & 64)

(4) In both appeals, PLUS and PROPEL contended that the JC was wrong at law to have upheld the award for loss of dependency and increased its amount to RM500.00 per month, when the evidence showed that the contribution from the deceased was for his younger siblings. The appellants failed to prove their claim that the deceased's monthly contribution to his parents was for his siblings. His father, the 1st respondent, testified that the deceased had contributed RM300.00 per month when he first started working, and later his contribution was increased to RM700.00, which went towards food, drinks, and utilities. The appellants did not adduce any evidence to counter the 1st respondent's testimony or to prove that the RM700.00 contribution from the deceased was for his siblings. The reason the JC allowed the respondents' cross-appeal on the quantum of the loss of dependency was because of the discrepancy between the pronouncement made by the SCJ in open court that the quantum of damages for loss of dependency was RM500.00 per month and the SCJ's grounds of judgment, where it was stated that the quantum for loss of dependency was RM300.00. The increase was not because she thought that the amount awarded by the SCJ was too low. Accordingly, there was no reason to interfere with the JC's decision as regards the quantum of damages for the respondents' loss of dependency. (paras 68-72)

Case(s) referred to:

Ahmad Rashidi Yahya & Anor v. Projek Lebuhraya Usahasama Berhad [2021] 6 MLRH 179 (refd)

AJS v. JMH & Another Appeal [2022] 1 MLRA 214 (refd)

Arab-Malaysian Finance Bhd v. Steven Phoa Cheng Loon & Ors [2002] 2 MLRA 319 (refd)

Burnside & Anor v. Emerson & Anor [1968] 1 WLR 1490 (folld)

Caparo Industries PLC v. Dickman [1990] UKHL 2 (distd)

Donoghue v. Stevenson [1932] AC 562 (refd)

Dr Kok Choong Seng & Anor v. Soo Cheng Lin & Another Appeal [2017] 6 MLRA 367 (refd)

Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1 (refd)

Gorringe v. Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council [2004] UKHL 15; [2004] 2 All ER 326 (refd)

Hamzah D 494 & Ors v. Wan Hanafi Bin Wan Ali [1975] 1 MLRA 531 (refd)

Hemraj & Co Sdn Bhd v. Tenaga Nasional Berhad [2023] 2 MLRA 25 (folld)

Iftikar Ahmed Khan v. Perwira Affin Bank Berhad [2018] 1 MLRA 202 (refd)

Latimer v. AEC Ltd [1953] 2 ALL ER 449 (refd)

LBS Travel Sdn Bhd & Satu Lagi lwn. Nathan Muthayah & Yang Lain [2018] MLRHU 1006 (refd)

Malaysian Motor Insurance Pool v. Tirumeniyar Singara Veloo [2019] 6 MLRA 99 (refd)

Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 (refd)

Parimala Muthusamy & Ors v. Projek Lebuhraya Utara-Selatan [1997] 3 MLRH 226 (refd)

Projek Lebuhraya Usahasama Berhad v. Abdul Azim John Abdullah [2022] MLRHU 998 (refd)

Projek Lebuhraya Utara-Selatan Berhad v. Hmd Rais Hussin A Mohamed Ariff [2010] 10 MLRH 391 (refd)

Samuel Naik Siang Ting v. Public Bank Berhad [2015] 5 MLRA 665 (refd)

Tan Kuan Yau v. Suhindrimani Angasamy [1985] 1 MLRA 183 (refd)

Tebin Mostapa v. Hulba-Danyal Balia & Anor [2020] 4 MLRA 394 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Malaysia v. Batu Kemas Industri Sdn Bhd & Another Appeal [2018] 4 MLRA 1 (refd)

Tengku Dato' Ibrahim Petra Tengku Indra Petra v. Petra Perdana Berhad & Another Case [2018] 1 MLRA 263 (refd)

Tetuan Wan Shahrizal Hari & Co v. PP [2023] 4 MLRA 11 (refd)

Topaiwah v. Salleh [1968] 1 MLRA 580 (refd)

UEM Group Bhd v. Genisys Integrated Engineers Pte Ltd & Anor [2010] 2 MLRA 668 (refd)

Vishnu Telagan v. Timbalan Menteri Dalam Negeri Malaysia & Ors [2019] 5 MLRA 83 (refd)

Woodland v. Swimming Teachers Association And Others [2014] AC 537 (folld)

Legislation referred to:

Federal Roads (Private Management) Act 1984, s 5

Highways Act 1980 [UK], s 41(1)

Counsel:

For Civil Appeal No: A-04(NCvC)(W)-444-10-2023

For the appellant: Krishna Dallumah (Thirunaaukarasu Thoppasamy & Yong Yoong Hui with him); M/s Thiru Jegatish & Associates

For the respondents: Ayleswary Bathamanathan; M/s Sudesh Narinder And Partners

For Civil Appeal No: A-04(NCvC)(W)-447-10-2023

For the appellant: Athithan Singaravelu (Illavarasi Thiruchelvam with him); M/s Athi & Seelan

For the respondents: Ayleswary Bathamanathan; M/s Sudesh Narinder And Partners

[For the High Court judgment, please refer to Projek Lebuhraya Usahasama Berhad & Anor v. Zakaria Hamid & Anor [2023] MLRHU 2479]

JUDGMENT

Faizah Jamaludin JCA:

Introduction

[1] The present appeals before us — W-04(NCvC)(W)-444-10/2023 ("Appeal 444") and W-04(NCvC)(W)-447-10/2023 ("Appeal 447") — have been filed by Projek Lebuhraya Usahasama Berhad ("PLUS") and Projek Penyelenggaraan Lebuhraya Berhad ("PROPEL"), respectively. These appeals challenge the decision of the Taiping High Court, which affirmed the Sessions Court's findings on liability relating to the fatal accident at KM177.8 of the Lebuhraya Utara-Selatan ("the Highway"), resulting in the death of motorcycle rider Azizi bin Zakaria ("the Deceased"). They also contest the High Court's decision in allowing the respondents' cross-appeal with regards to quantum.

[2] PLUS holds the concession for the Highway; PROPEL is its contractor for maintenance and repairs. The 1st and 2nd respondents are the parents of the Deceased. They had brought an action for negligence at the Taiping Sessions Court against PLUS, PROPEL, and Muhammed Azmer bin Jamel ("SD-2") for the death of their son. The Sessions Court found both PLUS and PROPEL negligent and had allocated 80% of the liability to them and 20% to the Deceased. It awarded the respondents the sum of RM57,600.00 for loss of dependency and the sum of RM3,000.00 as special damages.

[3] Upon appeal by PLUS and PROPEL, the High Court upheld the Sessions Court's decision regarding liability and allowed the respondents' cross-appeal, increasing the quantum of loss of dependency to RM500.00 per month.

[4] The appellants now appeal against the High Court's decision, contending that the learned Judicial Commissioner ("JC") was plainly wrong in upholding the Sessions Court's decision as regards liability and allowing the respondents' cross-appeal on quantum.

Background Facts

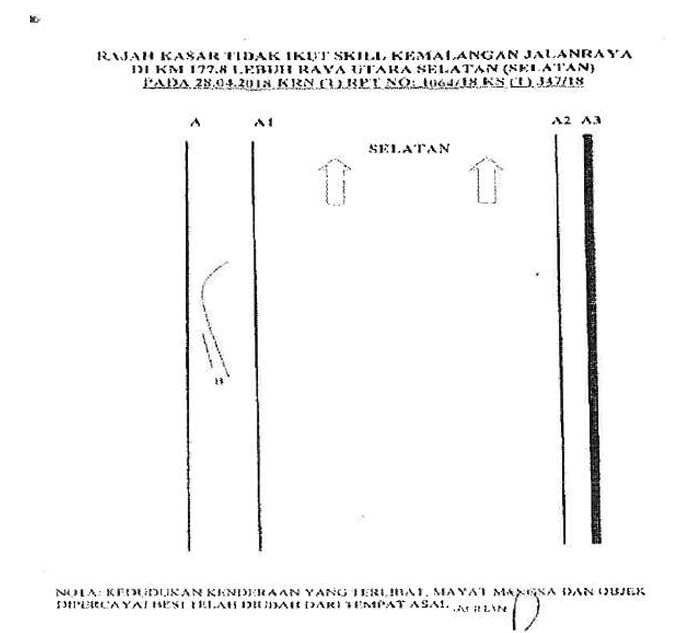

[5] On 27 April 2018, at about 11.45pm, the Deceased was riding along the Highway in a convoy with six other motorcyclists from Kuala Ketil, Kedah, to Banting, Selangor. At KM177.8 of the Highway, the Deceased hit a yellow-orange object along A1 (shown in the sketch plan below) and was flung off his motorcycle onto the middle of the highway at A1-A2; his motorcycle fell onto the side of the road along A1.

[6] Immediately after the Deceased's collision with the yellow-orange object, SD-2, who was riding in the convoy directly behind the Deceased, collided into the Deceased's motorcycle that had fallen along A1. As a result of the collision, SD-2 and his motorcycle fell and dragged the Deceased's motorcycle onto lane A-A1, which is the emergency lane.

[7] SD-2 was conscious after falling into lane A-A1 and switched on his hand-phone light to search for the Deceased. SD-2 saw the Deceased lying in the middle of lane A1-A2, and with the help of the members of the public who had stopped to help, carried the Deceased to lane A-A1. However, as a result of the excessive injury to his head, the Deceased succumbed to his injuries and died on location.

Principles Of Appellate Intervention

[8] The law on appellate intervention is trite. An appellate court must not interfere with the trial judge's conclusions on the primary facts unless it is satisfied that the trial judge was "plainly wrong". As explained by the Federal Court in Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 ("Ng Hoo Kui"):

[34] The 'plainly wrong' test operates on the principle that the trial court has had the advantage of seeing and hearing the witnesses on their evidence as opposed to the appellate court that acts on the printed records.

[9] In Malaysia, the Federal Court has held that a "plainly wrong decision" is a decision arrived at due to no or insufficient judicial appreciation of evidence and/or a material error of the law: see Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1; UEM Group Bhd v. Genisys Integrated Engineers Pte Ltd & Anor [2010] 2 MLRA 668; Tengku Dato'Ibrahim Petra Tengku Indra Petra v. Petra Perdana Berhad & Another Case [2018] 1 MLRA 263; and Ng Hoo Kui (supra).

[10] The Federal Court in Ng Hoo Kui reiterated that the "plainly wrong" test was not intended to be used by an appellate court as a means to substitute its own decision for that of the trial court on the facts. As long as the trial court's conclusion can be supported on a rational basis in view of the material evidence, the fact that the appellate court felt like it might have decided differently was irrelevant:

[148] .... As long as the trial judge's conclusion can be supported on a rational basis in view of the material evidence, the fact that the appellate court feels like it might have decided differently is irrelevant. In other words, a finding of fact that would not be repugnant to common sense ought not to be disturbed. The trial judge should be accorded a margin of appreciation when his treatment of the evidence is examined by the appellate courts.

[11] The Federal Court found in Ng Hoo Kui that the Court of Appeal had erroneously applied the "plainly wrong" test in a broad and general manner without identifying specifically why the trial judge's findings were plainly wrong on the key issues. It held that it was not sufficient for the Court of Appeal to reverse the findings of fact on a particular point of evidence merely because it disagreed with the trial judge's conclusion on whether one party or the other was to be believed on the evidence adduced. Although there might have been inconsistencies in the evidence — which meant that another judge might have reached a different conclusion — this was not relevant when considering if a trial judge's findings could be overturned. It held that unless the trial judge's conclusion was one that no reasonable judge would have made, his conclusion on the point should be left undisturbed.

[12] Thus, before this Court can intervene in the decision of the High Court in these appeals, we have to determine:

(a) whether the High Court in exercising its appellate function had correctly applied the "plainly wrong" test;

(b) whether the trial judge's conclusion was one that no reasonable judge would have made; and

(c) did the Sessions Court and/or the High Court arrive at their respective decisions due to no or insufficient judicial appreciation of the evidence and/or a material error of law.

(i) Liability

[13] The main issue in both these appeals is whether PLUS and/or PROPEL are liable for the condition of the Highway on the night of the accident. It is not disputed that the accident resulted from the Deceased hitting a yellow-orange object on the Highway, and the area was pitch black at the time of the accident: there were no street lights on the stretch of the Highway where the accident occurred. This was confirmed by SD-2 and the investigating officer ("SP-1"), who had arrived at the site approximately one hour after the accident.

[14] In a nutshell, the appellants' case is that the learned JC had erred in law and in fact in upholding the finding by the learned Sessions Court Judge ("SCJ") that the respondents had discharged their burden of proving that the Deceased's death was caused by PLUS and PROPEL's negligence, and allocating 80% of the liability to the appellants.

Statutory Duty

[15] Learned counsel for PLUS submits that the Highway Authority Malaysia (Incorporation) Act 1980 (Act 231) ("HA 1980") only imposes a duty on it to do all things reasonably necessary for the maintenance of the Highway. He cites, as authority, the English case of Gorringe v. Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council [2004] UKHL 15; [2004] 2 All ER 326, where the House of Lords held that "the duty to maintain the highway" under s 41(1) of the UK's Highways Act 1980, did not include a duty to take reasonable care to secure the highway was not dangerous to traffic.

[16] With respect to learned counsel, PLUS is the concession holder of the Highway. It is not the Highway Authority Malaysia. The Highway Authority Malaysia is Lembaga Lebuhraya Malaysia ("LLM"). It follows, therefore, that HA 1980 does not apply to PLUS. It applies to LLM. For this reason, we disagree that HA 1980 applies to PLUS.

[17] As the concession holder of the Highway, PLUS is authorised to demand, collect, and retain tolls on the said Highway. It has a statutory duty to maintain in good repair and condition the Highway under the Federal Roads (Private Management) Act 1984 (Act 306) ("FRA 1984"). Section 5 of the FRA 1984 states:

5. Duty to maintain road, bridge or ferry

Any person who is authorized to demand, collect and retain tolls under an order made under s 2 shall maintain in good repair and condition and in accordance with sound engineering practices the road, bridge or ferry in respect of which the order is made.

[18] The law is settled that in construing and interpreting statutes, where the words of a statute are unambiguous, plain and clear, Courts must give these words their natural and ordinary meaning and must apply the literal rule. It is only where the words in the statutes are ambiguous or where a literal reading of a provision bears more than one meaning, Courts may use the purposive approach: see the Federal Court's decisions in Tebin Mostapa v. Hulba-Danyal Balia & Anor [2020] 4 MLRA 394 and AJS v. JMH & Another Appeal [2022] 1 MLRA 214.

[19] The words in s 5 of the FRA 1984 are clear and unambiguous: any person who is authorised to demand, collect and retain tolls for a road, bridge or ferry shall maintain in good repair and condition, the said road, bridge or ferry, in accordance with sound engineering practices.

[20] In this instant case, PLUS, as the concession holder of the Highway, is authorised to demand, collect, and retain tolls from users of the Highway. Therefore, it has a statutory duty under s 5 of the FRA 1984 to maintain the Highway in good repair and condition in accordance with sound engineering practices.

Duty Of Care

[21] Learned counsel for PLUS submits that the learned JC had erred in fact and in law when she agreed with the SCJ that PLUS owed a duty of care towards the Deceased and that it had breached that duty of care, and is, thus, negligent. PLUS argues that, as a matter of public policy, it would not be just, fair, and reasonable to impose liability on it as this would open up floodgates to would-be plaintiffs for any incident on the Highway to make claims of negligence against PLUS, regardless of who was negligent.

[22] PLUS argues that liability should not be imposed on it, as the concessionaire of the Highway, for objects that had fallen or were thrown off vehicles using the Highway.

[23] The question before us is whether the Sessions Court and the High Court were plainly wrong on the issue that the appellants have a duty of care at common law towards the Deceased, when the appellants themselves did not plead in their Defence that they did not have any duty of care at common law towards the Deceased or the other users of the Highway.

[24] What PLUS and PROPEL had pleaded in para 3(a) of their Defence was that there was no foreign object in the Deceased's lane. In para 3(b), they had pleaded in the alternative that they had taken all reasonable steps to prevent any foreign object from being on the Highway. Para 3(b) of the appellants' defence is produced below:

3(b) Selanjutnya dan sebagai alternatifnya sekiranya terdapat sebarang benda asing di tempat tersebut, Defendan Pertama dan Defendan Kedua telah mengambil kesemua tindakan yang wajar dan munasabah untuk mengelakkan sebarang benda asing berada di jalanraya pada setiap masa dan sekiranya wujud sebarang benda asing ianya adalah satu perkara yang di luar kawalan Defendan Pertama dan Defendan Kedua pada masa tersebut dan sekiranya Si Mati, Azizi bin Zakaria terlibat dalam kemalangan jalanraya pada masa dan tempat tersebut, ianya adalah disebabkan oleh kecuaian atau kecuaian sumbangan Plaintif-Plaintif.

[25] It is trite that parties are bound by their pleadings: see Samuel Naik Siang Ting v. Public Bank Berhad [2015] 5 MLRA 665; and Iftikar Ahmed Khan v. Perwira Affin Bank Berhad [2018] 1 MLRA 202. Parties cannot raise defences and/or issues that were not pleaded in their Defence in this appeal. Therefore, PLUS and PROPEL cannot now deny that they have a duty of care towards the Deceased as a user of the Highway.

[26] Similarly, in their appeal to the High Court, as reflected in the appellants' submissions, the appellants did not contend that they did not have a duty of care to the Deceased. Rather, their position was that they had exercised reasonable care in fulfilling their obligations to ensure the safety of road users. Paras 5.5 and 5.13 of the PLUS's submission at the High Court are produced below:

5.5 Kesemua Langkah ini menunjukkan Defendan telah mengambil "reasonable care" dalam memenuhi tanggungjawabnya untuk menjaga keselamatan pengguna jalan raya.

5.13 Berasaskan penghujahan di atas adalah dihujahkan bahawa Defendan telah mengambil kesemua langkah yang munasabah untuk mengawasi untuk mengesan dan mengalih halangan di jalanraya untuk memudahkan perjalanan pengguna jalanraya dan Defendan tidak cuai dalam apa jua cara.

[27] The learned JC did not address the question of whether PLUS or PROPEL owed a duty of care to the Deceased. We find that this was not erroneous of her, as the appellants had not pleaded that they lacked such a duty toward the Deceased. In para 22 of her grounds of judgment, she considered the English case of Burnside & Anor v. Emerson & Anor [1968] 1 WLR 1490 and referenced the legal principle articulated in Gorringe v. Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council (supra), which holds that the existence of a statutory duty does not automatically give rise to a corresponding common law duty of care on the part of the relevant authority to the individuals or classes of persons for whom the statute is intended.

[28] Burnside v. Emerson (supra) is a UK Court of Appeal decision in an action for non-feasance against a highway authority. Lord Denning M.R. said the following as regards a highway authority's duty to maintain the highway:

There is a duty on a highway authority to maintain the highway; and "maintain" includes repair. If it is out of repair, they fail in their duty: and if damage results, they may now be made liable unless they prove that they used all reasonable care. The action involves three things:

First: The plaintiff must show that the road was in such a condition as to be dangerous for traffic. In seeing whether it was dangerous, foreseeability is an essential element. The state of affairs must be such that injury may reasonably be anticipated to persons using the highway.

Second: The plaintiff must prove that the dangerous condition was due to a failure to maintain, which includes a failure to repair the highway. In this regard, a distinction is to be drawn between a permanent danger due to want of repair, and a transient danger due to the elements. When there are potholes or ruts in a classified road which have continued for a long time unrepaired, it may be inferred that there has been a failure to maintain. When there is a transient danger due to the elements, be it snow or ice or heavy rain, the existence of danger for a short time is no evidence of a failure to maintain.

Third: If there is a failure to maintain, the highway authority is liable prima facie for any damage resulting therefrom. It can only escape liability if it proves that it took such care as in all the circumstances was reasonable.

[Emphasis Added]

[29] Learned counsel for PLUS argues that as a matter of public policy, it would not be just, fair, and reasonable to impose liability on it for the Deceased's death. He cites as authority the cases of Arab-Malaysian Finance Bhd v. Steven Phoa Cheng Loon & Ors [2002] 2 MLRA 319 ("Steven Phoa"); Tenaga Nasional Malaysia v. Batu Kemas Industri Sdn Bhd & Another Appeal [2018] 4 MLRA 1 ("Batu Kemas"). He also referred to the High Court's decision in Projek Lebuhraya Utara-Selatan Berhad v. Hmd Rais Hussin A Mohamed Ariff [2010] 10 MLRH 391 on whether the appellant had taken all reasonable steps to prevent wild boars or other animals from straying onto the Highway.

[30] With respect to learned counsel for PLUS, the question before the Federal Court in Steven Phoa and Batu Kemas was whether to impose liability on the local authority and TNB, respectively, for the economic loss suffered by the respondents in those cases. The Federal Court in Batu Kemas adopted the "three-fold test" in Caparo Industries PLC v. Dickman [1990] UKHL 2, where the House of Lords held that for a duty of care to arise in negligence, three elements must be present. They are (i) the harm must be reasonably foreseeable; (ii) there must be a proximity of relationship between the parties; and (iii) it must be just, fair, and reasonable to impose liability.

[31] Whereas, the issue before us in these appeals is not liability for economic loss caused by the appellants' negligence, but for the death caused to the Deceased. Injury and death is one of the established categories of liability. The Federal Court in Batu Kemas held that where a case falls within one of the established categories of liability, the third element of the Caparo v. Dickman test does not arise. Jeffery Tan FCJ, in delivering the decision of the Federal Court, said:

[66] In Malaysia, the 'fair, just and reasonable' element is well established in cases concerned with economic loss and public services. Still it should be said that where a case fell within the established categories of liability, 'a defendant should not be allowed to seek to escape from liability by appealing to some vague concept of justice and fairness' as the previous authorities 'have by necessarily implication held that it is fair, just and reasonable that the claimant should recover' (Clerk & Lindsell at para 8-24 citing Hobhouse LJ in Perrett v. Collins [1999] PNLR 77). Where a case falls within one of the established categories of liability, the Caparo three-fold test, which is to determine the duty of care in a new and novel situation, is inapplicable. Where a case falls within one of the established categories of liability, the third element in Caparo does not arise, as the previous authorities 'have by necessarily implication held that it is fair, just and reasonable that the claimant should recover'.

[Emphasis Added]

[32] Accordingly, the third element of the Caparo v. Dickman test does not arise in determining whether PLUS has a duty of care at common law towards the Deceased. All the previous authorities — starting from Donoghue v. Stevenson [1932] AC 562 — have held by necessary implication that it is fair, just and reasonable that the claimant should recover if it can show that the harm to the claimant is reasonably foreseeable and there is a relationship of proximity between the tortfeasor and the claimant.

[33] Based on the facts and circumstances of this case, we find that PLUS does owe the Deceased a duty of care at common law to maintain the Highway in good repair and condition. This is because (i) the harm to users of the Highway caused by PLUS' or its contractors' failure to maintain the Highway in good repair and condition is reasonably foreseeable; and (ii) there is a proximity of relationship between the Highway users and PLUS.

[34] What does "maintain in good repair and condition" mean? Based on Burnside v. Emerson (supra), first, the Highway must be in such a condition as to be dangerous for traffic; secondly; the dangerous condition was due to a failure to maintain, which includes a failure to keep it in good repair and condition; and thirdly, if there is a failure to maintain, PLUS is liable prima facie for any damage resulting therefrom. In order to escape liability, PLUS must prove that it took such care as, in all the circumstances, was reasonable.

Did PLUS Take Reasonable Care?

[35] Thus, the next question is whether PLUS took reasonable care in the circumstances.

[36] PLUS contends that it had taken reasonable care to ensure the safety of all the Highway users by erecting fences to prevent any entry of objects, and having PLUSRonda patrol the area at intervals of 45-50 minutes. It cites the case of Hamzah D 494 & Ors v. Wan Hanafi Bin Wan Ali [1975] 1 MLRA 531, where the Federal Court adopted the principle in Latimer v. AEC Ltd [1953] 2 All ER 449, that measures that should be taken are what a reasonably prudent man would have taken in the circumstances.

[37] Both SP-1 and SD-2 testified that the stretch of the Highway on which the accident occurred was pitch black (gelap gelita). One of the dangers to users on the Highway is foreign objects on the road, that may have been left by road users or others, or dropped from vehicles using the Highway. In this instant case, it was a yellow-orange object — identified as a wheel chock for trucks and trailers. In Ahmad Rashidi Yahya & Anor v. Projek Lebuhraya Usahasama Berhad [2021] 6 MLRH 179, the foreign object was a grey iron block. The High Court in Ahmad Rashidi allocated 40% of the liability to PLUS and 60% to the plaintiff.

[38] The Court of Appeal affirmed the High Court's decision in Ahmad Rashidi. However, it is not evident in Ahmad Rashidi when the accident took place — whether it was light or dark — since the time of the accident was not stated in the High Court's judgment and the Court of Appeal did not issue any grounds of judgment. Therefore, we find no merit in the PLUS's argument that the learned JC should have distinguished Ahmad Rashidi by the colour of the object on the Highway.

[39] Learned counsel for PLUS submitted that the learned JC fell into error by relying on the High Court's decisions in LBS Travel Sdn Bhd & Satu Lagi lwn. Nathan Muthayah & Yang Lain [2018] MLRHU 1006 and Parimala Muthusamy & Ors v. Projek Lebuhraya Utara-Selatan [1997] 3 MLRH 226 when both these decisions were reversed by the Court of Appeal. With respect to learned counsel for PLUS, a careful reading of the learned JC's grounds of judgment shows that she did take into account that the High Court's decisions in LBS Travel and Parimala had been reversed by the Court of Appeal. As regards LBS Travel, Her Ladyship stated at para 25 of the GOJ in item 5 of the table "COA reversed the HC order on 3 October 2019". In para 27, she said, "Although it has been reversed by the Court of Appeal, as far as I am aware, there is no written grounds." As for Parimala, the learned JC only listed it as one of the cases that involved PLUS, and she did not analyse the decision of the High Court in that case.

[40] Moreover, there are no written grounds of judgment in both LBS Travel and Parimala. It is settled law that without written grounds of judgment, the decision of a higher court is not binding under the principle of stare decisis on a lower Court: see Tetuan Wan Shahrizal Hari & Co v. PP [2023] 4 MLRA 11; Vishnu Telagan v. Timbalan Menteri Dalam Negeri Malaysia & Ors [2019] 5 MLRA 83; and Malaysian Motor Insurance Pool v. Tirumeniyar Singara Veloo [2019] 6 MLRA 99.

[41] For these reasons, we find that the learned JC did not fall into error by citing decisions of the High Court in both LBS Travel and Parimala in her grounds of judgment.

[42] Is providing patrols at 45-50 minutes intervals by PLUSRonda reasonable in the circumstances — is it a measure that a reasonably prudent man would have taken in the circumstances? Both the Sessions Court and the High Court held that the steps taken by the appellants were not reasonably sufficient in the circumstances, and allocated 80% of the liability on both PLUS and PROPEL.

[43] We do not agree with the arguments presented by PLUS and PROPEL that the establishment of PLUSRonda to patrol the 800km stretch of the Highway constitutes the taking of all reasonable measures to ensure user safety.

[44] In our view, establishing PLUSRonda is only one of the steps to ensure the Highway is maintained in good order and condition to ensure that it is safe for road users. PLUSRonda patrols the Highway in big vehicles. In an unlit stretch of the Highway, with no street lights, the PLUSRonda personnel will only be able to see what is on the road in front of their vehicle. In this case, SP-1 testified that he did not see the yellow-orange object when he patrolled the road approximately 20 minutes before the accident. In fact, SP-1 said that even when he came back to the site after the accident, he was not able to see the yellow-orange object on the road. When asked by the learned SCJ why he wrote that the accident was caused by hitting an object on the road, SP-1 said it was based on what he was told by the motorcyclists at the accident site.

[45] Nevertheless, we also disagree with the High Court in LBS Travel, Ahmad Rashidi and Projek Lebuhraya Usahasama Berhad v. Abdul Azim John Abdullah [2022] MLRHU 998, that PLUS must immediately remove any foreign object or obstruction on the Highway to satisfy their duty of care or statutory obligations. We find that imposing such an immediate requirement is not reasonable under the circumstances.

[46] We do, however, agree with the submission by learned counsel for PROPEL that there ought to be a reasonable time for PLUS and/or PROPEL to discover or be informed of objects on the Highway and for it to arrive at the scene and remove the object.

[47] The reasonable response time may range from 10 minutes to 30-45 minutes, depending on whether the object is detected directly by a PLUSRonda patrol vehicle or reported by road users, as well as the distance between the object and the nearest PLUSRonda base. PLUS and/or PROPEL should, in consultation with relevant experts, develop a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) that clearly outlines both the process and timeline for removing foreign objects from the Highway.

[48] It is observed that in several instances, including this case and Abdul Azim John (supra), accidents occurred due to motorists being unable to see obstructions on the Highway at night when the area was unlit. On unlit roads at night, typically only the dividing lines painted with reflective paint or the road reflectors, commonly referred to as "cat's-eye", are visible.

[49] Therefore, it is our considered opinion that a reasonable course of action in the circumstances would be for PLUS to install street lighting at intervals of, for instance, 300 meters or another distance deemed appropriate, in accordance with established engineering practices. Furthermore, with the introduction of solar-powered street lights, operational expenses are expected to be significantly reduced compared to those associated with conventionally powered lighting systems.

[50] For these reasons, we find that in the circumstances that PLUS did not take reasonable steps to maintain and keep the Highway in good repair and condition.

Is PLUS's Duty To Maintain And Repair The Highway Delegable?

[51] Learned counsel for PLUS argues that its duty to maintain and repair the Highway is delegable based on the decision of the Federal Court in Hemraj & Co Sdn Bhd v. Tenaga Nasional Berhad [2023] 2 MLRA 25 ("Hemraj v. TNB"). PLUS contends that because it had appointed PROPEL as its independent contractor to maintain and repair the Highway, PLUS is not liable for the damage caused to users of the Highway as a result of its negligence.

[52] What is a non-delegable duty of care? Lord Sumption in Woodland v. Swimming Teachers Association And Others [2014] AC 537 ("Woodland"), explained that the expression "non-delegable duty" has become the conventional way of describing those cases in which the ordinary principle is displaced; the duty extends beyond being careful, to procuring the careful performance of work delegated to others.

[53] The Federal Court in Hemraj v. TNB held that renovation works carried out by a homeowner through its independent contractor were delegable because it was not hazardous. However, it held, citing with approval Lord Sumption's judgment in Woodland, that operations relating to hazards in a public place such as a highway are non-delegable. Zabariah Yusoff FCJ said:

[56] There are further examples of non-delegable duties of care, namely, dangerous operations on the highway.

[54] Lord Sumption in Woodland held that "highway and hazards" cases are examples of non-delegable duties of care. The Federal Court in Hemraj v. TNB explained that in order for a duty of care relating to work on a highway to be non-delegable, the work must be hazardous.

[55] Apart from the "highway and hazards" cases, Lord Sumption had set out characteristics of five elements that would give rise to non-delegable duties of care. They are:

23 ... If the highway and hazard cases are put to one side, the remaining cases are characterised by the following defining features:

(1) The claimant is a patient or a child, or for some other reason is especially vulnerable or dependent on the protection of the defendant against the risk of injury. Other examples are likely to be prisoners and residents in care homes.

(2) There is an antecedent relationship between the claimant and the defendant, independent of the negligent act or omission itself, (i) which places the claimant in the actual custody, charge or care of the defendant, and (ii) from which it is possible to impute to the defendant the assumption of a positive duty to protect the claimant from harm, and not just a duty to refrain from conduct which will foreseeably damage the claimant. It is characteristic of such relationships that they involve an element of control over the claimant, which varies in intensity from one situation to another, but is clearly very substantial in the case of school children.

(3) The claimant has no control over how the defendant chooses to perform those obligations, ie whether personally or through employees or through third parties.

(4) The defendant has delegated to a third party some function which is an integral part of the positive duty which he has assumed towards the claimant; and the third party is exercising, for the purpose of the function thus delegated to him, the defendant's custody or care of the claimant and the element of control that goes with it.

(5) The third party has been negligent not in some collateral respect but in the performance of the very function assumed by the defendant and delegated by the defendant to him.

[56] The Federal Court in Dr Kok Choong Seng & Anor v. Soo Cheng Lin & Another Appeal [2017] 6 MLRA 367 ("Dr Kok Choong Seng") held that the principle of non-delegable duty applies in Malaysia. Raus Sharif CJ in Dr Kok Choong Seng highlighted that Lord Sumption in Woodland had stressed that non-delegable duties of care should be imputed "only so far as it would be fair, just and reasonable".

[57] Work relating to the maintenance and repair of a highway, including on this Highway, which is the main highway connecting the north and south of Malaysia and Singapore, is hazardous due to the amount of vehicles that go up and down the highway on a daily basis. On this point alone, based on Woodland and Hemraj v. TNB, since maintenance of a highway falls within the "highway and hazards" cases, PLUS's duty of care to maintain in good repair and condition the Highway is non-delegable.

[58] Moreover, we find that the elements outlined in Lord Sumption's list apply to PLUS's duty to maintain the Highway. This is due to several factors: first, users of the Highway have no control over how PLUS chooses to perform its obligation to maintain the Highway, whether through its employees or third parties. Second, PLUS delegated its duty to maintain Highway to PROPEL, granting PROPEL both the responsibility for maintenance and the associated duty of care towards Highway users, including the relevant element of control that goes with it. Third, PROPEL has been negligent not in some collateral respect but in the performance of the very function assumed by PLUS and delegated to PROPEL.

[59] Accordingly, for these reasons, we find that PLUS's duty of care at common law to the users of the Highway to maintain the Highway in good repair and condition is non-delegable. Therefore, although PLUS had delegated its duty to maintain and repair the Highway to PROPEL, it remains liable for PROPEL's negligence that results in damage or injury to the users of the Highway.

[60] As discussed above, this duty may be discharged by taking reasonable steps, which in our view includes removing foreign objects/obstructions from the Highway within a reasonable time period and placing street lights at reasonable intervals on the Highway in order to minimise the danger at night caused by these objects/obstructions for users of the Highway.

[61] Therefore, we find that PLUS and PROPEL have not taken reasonable steps to discharge their duty of care to the Deceased.

[62] Accordingly, based on the facts and the circumstances of the case, and the applicable law, we do not find that the Sessions Court was plainly wrong in its decision as regards its finding of liability and its allocation of liability to the appellants and the Deceased.

[63] Further, we find that the High Court was not plainly wrong in upholding the Sessions Court's decision. As is evident from her grounds of judgment, the learned JC had considered the evidence adduced during the trial as well as the SCJ's grounds of judgment and the submissions of the parties before concluding that she did not see it fit to interfere with the factual findings of the learned SCJ since she was not "plainly wrong" in arriving at her findings of facts. The learned JC noted in para 21 of her grounds of judgment that the trial judge had given a reasoned judgment and applied the relevant laws in arriving at her decision.

[64] Therefore, we find that there is no basis for appellate intervention in the High Court's determination on liability.

(ii) Quantum

[65] It is a settled principle of law that in an appeal on quantum of damages, an appellate court will only intervene in matters of quantum where there is a misapprehension of the facts or an error in the assessment by the judge who awarded the costs. An appeal court should not interfere in the award of damages just because it thinks that if it had heard the case, it would have awarded a higher or lesser sum.

[66] The Federal Court in Tan Kuan Yau v. Suhindrimani Angasamy [1985] 1 MLRA 183, held that an appeal court should be disinclined to interfere with the trial judge's award of damages. An appeal court ought to intervene in the quantum of damages awarded only if (a) the judge failed to take into account some relevant consideration or took into account some irrelevant consideration, or (b) the amount is so excessive or so insufficient as to be plainly unreasonable. Abdul Hamid Omar CJ (Malaya) (as he then was) said:

Now, in an appeal on quantum of damages, it is essential in order to come to a conclusion to bear in mind certain principles which are well established. The appeal Court is slow, indeed, disinclined to interfere with the Judge's finding merely because the appeal Court thinks that if the case had been before it in the first instance a lesser sum would have been awarded.

..........

The principle on which the Court of Appeal reviews the assessment of damages, whether too high or too low, is not because the Court of Appeal might have given rather more or rather less, but only (1) if the Judge has omitted some relevant consideration or admitted some irrelevant consideration, or (2) if the amount is so excessive, or insufficient, as to be plainly unreasonable.

[67] This is in line with the Federal Court's earlier decision in Topaiwah v. Salleh [1968] 1 MLRA 580, where Azmi CJM (as he then was) delivering the judgment of the Federal Court said:

In order to justify reversing the trial Judge on the question of the amount of damages it will generally be necessary that this Court should be convinced either that the Judge acted on some wrong principle of law, or that the amount awarded was so extremely high or so very small as to make it an entirely erroneous estimate of the damages to which the plaintiff is entitled. (See Flint v. Lovell [1935] 1 KB 354).

[68] In both these appeals before us, PLUS and PROPEL contend that the learned JC was wrong at law to have upheld the award for loss of dependency and increased its amount to RM500.00 per month, when the evidence shows that the contribution from the Deceased was for his younger siblings.

[69] From our perusal of the evidence presented during the trial, the appellants failed to prove their claim that the Deceased's monthly contribution to his parents was for his siblings. His father — the 1st respondent ("SP-3") testified that the Deceased had contributed RM300.00 per month when he first started working, and later his contribution was increased to RM700.00. SP-3 testified during the trial that the RM700.00 contributed from the Deceased went towards food and drink, and utilities.

[70] The appellants did not adduce any evidence to counter SP-3's testimony or to prove their case that the RM700.00 contribution from the Deceased was for his siblings.

[71] The reason the learned JC allowed the respondents' cross-appeal on the quantum of the loss of dependence was because of the discrepancy between the pronouncement made by the SCJ in open court on 24 May 2022 that the quantum of damages for loss of dependency was RM500.00 per month and that in the draft judgment and the SCJ's grounds of judgment, where it was stated that the quantum for loss of dependency of RM300.00. The increase was not because Her Ladyship thought that the amount awarded by the Sessions Court was too low.

[72] Accordingly, we see no reason to interfere with the learned JC's decision as regards the quantum of damages for respondents' loss of dependency.

Decision

[73] For the above reasons, Appeal 444 and Appeal 447 are dismissed with costs. The Order of the High Court dated 11 May 2023 is affirmed.

[74] "Tarikh Penghakiman" in the Sessions Court's Order dated 24 May 2022 means the date of the judgment of the Sessions Court.

[75] Costs of RM40,000.00 in total for both appeals, subject to allocatur.