High Court Malaya, Kuala Lumpur

Arziah Mohamed Apandi JC

[Civil Appeal No: WA-12BNCVC-83-10-2021]

4 November 2024

Legal Profession: Misconduct — Touting — Whether introduction of client to law firm amounted to touting — Whether arrangement between parties were legitimate professional arrangement — Whether appellant contracted with respondents as investor — Whether appellant entitled to recoup investments made from respondents

Contract: Oral agreement — Upfront payment of litigation costs ('fees') in exchange for share of successful litigation — Whether agreement subsequently documented — Whether agreement signed under duress — Whether there was valid consideration for undertaking — Whether there were binding obligations — Whether conditions for return of fees met

In 2009, JKR Terengganu awarded lndah Sebati Sdn Bhd ('ISSB') a contract for a project and the appellant was an investor for the said project. Unknown to the appellant, JKR Terengganu ('JKR') had terminated the contract with ISSB in September 2013. When this was discovered, ISSB wanted to sue JKR but lacked funds for legal fees. The appellant then referred ISSB to the respondents' law firm and stepped forward to fund the litigation by paying the respondents' legal fees of RM80,000.00 for two cases, one against JKR Terengganu and another against KUBB Land Sdn Bhd. The appellant claimed that the 2nd respondent verbally agreed that he would ensure that the appellant would receive 15% of any judgment sum from the JKR case if she paid the legal fees. This verbal agreement was allegedly later documented in a 29 September 2017 letter signed by the 2nd respondent ('the Agreement Letter'). When the litigation succeeded with a judgment sum of RM5,130,537.60, the respondents received their fees from the Malaysian Department of Insolvency ('Insolvency Department') in August 2019 but declined to honour their undertaking to the appellant. Hence, the appellant commenced an action against the respondents in the Sessions Court. The Sessions Court Judge ('SCJ') however dismissed the appellant's claim on the grounds that: (i) there was no evidence of a verbal agreement in 2014; (ii) the Agreement Letter was signed under duress after threats and harassment; (iii) there was no valid consideration for the undertaking, and (iv) the undertaking was void and unenforceable. Aggrieved, the appellant appealed.

Held (allowing the appeal):

(1) The Agreement Letter was an outright agreement between the appellant and the respondents where in consideration of the appellant paying the RM80,000.00 legal fees for the respondents' client ISSB for the two suits, the respondents undertook to pay the appellant 15% from the judgment sum they won in the two cases for ISSB. The Agreement Letter represented a legitimate arrangement in which the appellant agreed to pay costs upfront to enable the legal work to proceed in exchange for a share of the eventual recovery. This created binding obligations between the parties. Hence, the trial judge erred in finding the Agreement Letter, a fee-sharing agreement, invalid for lack of consideration. (paras 32-33)

(2) The trial judge did not decide whether there was consideration but concluded the Agreement Letter was void due to the failure to prove the verbal undertaking. However, the trial judge should consider whether there was consideration or not to determine if the Agreement Letter was a binding contract. The focus on proof of the verbal undertaking was misconstrued when the objective was to ascertain whether the Agreement Letter was enforceable or not. Analysis should be done on the parties' actions after the execution of the Agreement Letter to determine the existence of compliance to the terms contained therein. (para 48)

(3) While the trial judge found the Agreement Letter was obtained through coercion, the evidence presented did not support this conclusion. The allegations of threats and disturbances were based mainly on hearsay testimony. The respondents did not produce police reports or other direct evidence to substantiate their claims of harassment and coercion. The allegations of coercion were based on the testimony from the respondents' witnesses, who admitted that they did not directly witness the alleged incidents. The respondents also failed to provide any corroborating evidence of threats or coercion. The failure to file any police report was fatal to the respondents' allegation of threats or coercion against the appellant as it could be construed as a bare allegation. (para 50)

(4) The trial judge failed to properly consider that fee-sharing arrangements between solicitors and referring parties when properly structured and disclosed, could be legitimate under professional conduct rules. The agreement appeared to be transparent about the fee-sharing terms. The Agreement Letter involved legitimate legal proceedings in the two suits. The fee-sharing terms were translated into a written document that was agreed upon by both parties. Such arrangements could promote access to justice by allowing parties to obtain legal representation that they otherwise could not afford. The trial judge's rejection of the Agreement Letter without considering its legitimate purpose was an error in law and fact. (paras 55-56)

(5) The appellant provided proof of the advance payment of legal costs, which enabled the litigation to proceed. Allowing the respondents to retain the full benefit after accepting those payments would create an unjust enrichment. The respondents benefited from the RM80,000.00 advanced costs. The appellant's contribution directly enabled the successful litigation. The appellant had fulfilled her obligations under the Agreement Letter. The respondents benefited from the funding but sought to avoid their agreed contractual obligations. (para 60)

(6) A mere client introduction to a law firm did not ipso fact amount to touting. Touting specifically involved arrangements where fees or commissions were shared purely in exchange for bringing clients to the firm. On the facts of the case, the arrangement between the appellant and the respondents was a legitimate professional arrangement between the law firm, including its partners, and the company's investor. A careful examination of the nature of the arrangement between the parties that led to the arrangement dictated by the Agreement Letter showed that it was not touting. Instead, the appellant contracted with the respondents as the investor of ISSB, and she wanted to recoup her investment previously made. (paras 70 & 72)

(7) The Legal Profession (Practice and Etiquette) Rules 1978 ('Rules') aimed to prohibit arrangements where intermediaries profited solely from referring clients without any legitimate connection to the litigation. The Rules did not prohibit legitimate business arrangements where client introduction was incidental to substantive involvement in financing and facilitating litigation. The appellant's introduction of ISSB to the respondents formed part of a broader legitimate business arrangement stemming from her position as an investor and financier. The subsequent undertaking was grounded in these legitimate interests rather than being payment for touting. The relationship between the parties extended well beyond mere client referral for commission, grounded in the appellant's legitimate role as investor and financier of the litigation. (para 73)

(8) The fees were paid to enable the JKR suit to proceed when ISSB lacked funds. Without the appellant's payment of fees, the cases could not have proceeded. The condition triggering the obligation to return the fees had been met. The Insolvency Department had made the payments to the respondents on 27 August 2019 and this payment had satisfied the condition specified in the undertaking for the return of the fees. Therefore, the appellant's entitlement to the return of RM80,000.00 was proven by the express written undertaking, the payment of the fees by the appellant, fulfilment of the conditions triggering the return obligation and proof of payment and receipt of funds from the Insolvency Department. This claim stood regarding the validity of the respondents' undertaking as it represented actual funds paid by the appellant for which a clear promise of return was made and the conditions for return had been satisfied. (paras 84-85)

Case(s) referred to:

Balakrishnan Devaraj v. Patwant Singh Niranjan Singh & Anor [2004] 3 MLRH 235 (distd)

Bar Malaysia v. Index Continent Sdn Bhd [2016] 1 MLRA 559 (refd)

Bhavanash Sharma Gurchan Singh Sharma (mengamal Di Bawah Nama Dan Gaya Bhavanash Sharma ) v. Jagmohan Singh Sandhu [2021] MLRHU 1150 (refd)

China Airlines Ltd v. Maltran Air Corp Sdn Bhd & Another Appeal [1996] 1 MLRA 260 (refd)

Dream Property Sdn Bhd v. Atlas Housing Sdn Bhd [2015] 2 MLRA 247 (refd)

First National Bank of Chicago v. Lam Thoo Sang & Ors [1978] 1 MLRH 548 (folld)

Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1 (refd)

Halimah Abdul Rahman v. Fatimah Abdullah [1976] 1 MLRA 446 (folld)

Koid Hong Keat v. Rhina Bhar [1989] 1 MLRH 766 (refd)

Lee Kuang Guat v. Chiang Woei Chien [2020] MLRAU 335 (refd)

Leong Hoong Khie v. PP & Another Case [1984] 1 MLRA 599 (refd)

Malaysia British Assurance Bhd v. Sihazko Sdn Bhd & Ors [2004] 2 MLRH 612 (refd)

Nasir Kenzin & Tan v. Elegant Group Sdn Bhd [2008] 2 MLRA 628 (refd)

Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 (refd)

Ong Leong Chiou & Anor v. Keller (M) Sdn Bhd & Ors [2021] 4 MLRA 211 (refd)

Paldraman Palaniappan & Ors v. Lachemi Sanganayar [1992] 2 MLRH 221 (refd)

Re Choe Kuan Him Advocate & Solicitor; T Damodaran v. Choe Kuan Him [1976] 1 MLRA 118 (refd)

Sarmiina Sdn Bhd v. Gerry Ho & Ors [2023] 2 MLRA 599 (refd)

Semenda Sdn Bhd & Anor v. CD Anugerah Sdn Bhd & Anor [2010] 2 MLRA 328 (refd)

Soo Lip Hong v. Tee Kim Huan [2005] 1 MLRA 801 (refd)

Tengku Dato Ibrahim Petra Tengku Indra Petra v. Petra Perdana Berhad & Another Case [2018] 1 MLRA 263 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Contracts Act 1950, ss 2, 10(1), 24(a), (e), 26

Evidence Act 1950, ss 6, 7, 59, 60, 101, 102, 114(g)

Legal Profession (Practice And Etiquette) Rules 1978, rr 51, 52

Legal Profession Act 1976, s 37

Solicitors' Account Rules 1990, r 7

Other(s) referred to:

R Sarma, Third party Litigation Funding In Canada - Validity, Regulatory Challenges And Navigating Through Champerty And Maintenance, 2022, p 107

S Ramalingam, "Contingency Fees and Third-Party Litigation Funding: Should Malaysia's Legal Profession Embrace It?" [2023] 4 MLJ xxv-xlvi

Counsel:

For the plaintiff: Alani Farhah Mohd Farouk; M/s Haris Ibrahim Kandiah Partnership

For the defendant: Ravvenneah Kalisvaran; M/s Kumar Partnership

JUDGMENT

Arziah Mohamed Apandi JC:

Introduction

[1] This appeal spotlights a critical intersection between access to justice and legal ethics, examining whether an investor who funds litigation costs can legitimately contract with lawyers to share successful cases' proceeds. At its heart lies a written undertaking by the Respondent law firm to share 15% of judgment proceeds with the Appellant, who had advanced RM80,000.00 in legal fees to enable litigation that ultimately succeeded. The Sessions Court struck down this arrangement, finding it void for lack of consideration and contrary to professional conduct rules.

[2] The facts unfold against a backdrop where Indah Sebati Sdn Bhd (ISSB) facing financial constraints, required funding to pursue legitimate claims against JKR Terengganu. The Appellant, already an investor in ISSB, stepped forward to fund the litigation by paying the Respondents' legal fees. The Respondents subsequently documented their undertaking to share proceeds in a letter dated 29 September 2017. When the litigation succeeded with a judgment of RM5,130,537.60, the Respondents received their fees but declined to honour their undertaking to the Appellant.

Background Of Claim

[3] Sometime in July or August 2009, JKR Terengganu awarded ISSB a contract for the SKTAI Project. In early 2013, ISSB invited the Appellant to invest RM335,000.00 to help complete the project when it faced financial difficulties. The Appellant invested the money, and in March 2013, an Investment Agreement was signed, giving her rights to 50% of ISSB's profits from the project. ISSB had repaid RM100,000.00 of her investment by January 2014.

[4] Unknown to the Appellant then, JKR Terengganu had terminated ISSB's contract in September 2013. When this was discovered, ISSB wanted to sue JKR but lacked funds for legal fees. The Appellant then referred ISSB to the Respondents' law firm and agreed to pay the initial legal fees of RM80,000.00 for two cases - one against JKR Terengganu and another against KUBB Land Sdn Bhd.

[5] The Appellant claims that in 2014, the 2nd Respondent verbally agreed that they would ensure she receives 15% of any judgment sum from the JKR case if she paid the legal fees. This verbal agreement was allegedly later documented in a 29 September 2017 letter signed by the 2nd Respondent ("the Agreement Letter"). In August 2017, ISSB won the case against JKR and was awarded RM5,130,537.60. The Respondents received their legal fees of RM1,097,807.78 from the Insolvency Department in August 2019 but refused to pay the Appellant.

The Defence

[6]The Respondents deny giving any verbal undertaking in 2014 to share their legal fees with the Appellant. They contend that the Appellant willingly paid the initial legal fees to protect her interests as an investor in ISSB, as without the lawsuits being filed, she would have no chance of recovering her investment.

[7]The Respondents argue that the Agreement Letter was signed under duress and coercion from the Appellant's husband, Jaafarul, who allegedly created commotions at their office and damaged property. They claim he brought a draft of the Agreement Letter and forced the 2nd Respondent to sign it by threatening the safety of the firm's staff and family members.

[8]The Respondents further contend that the Agreement Letter is void and unenforceable as it lacks consideration. They argue that the RM80,000.00 paid was purely for legal fees for services rendered and not consideration for fee sharing. Additionally, they argue that such fee-sharing agreements between lawyers and third parties amount to prohibited "touting" under legal profession rules.

[9]The Respondents also point out that the Appellant had already successfully sued ISSB directly and was awarded RM1,250,000.00 as a return on her investment. They argue that her current claim against them amounts to unjust enrichment as she is attempting to profit twice from the same matter.

[10] In essence, while the Appellant claims enforcement of what she characterises as a valid solicitor's undertaking with consideration, the Respondents maintain it was an invalid agreement obtained through coercion, without consideration, and contrary to professional conduct rules.

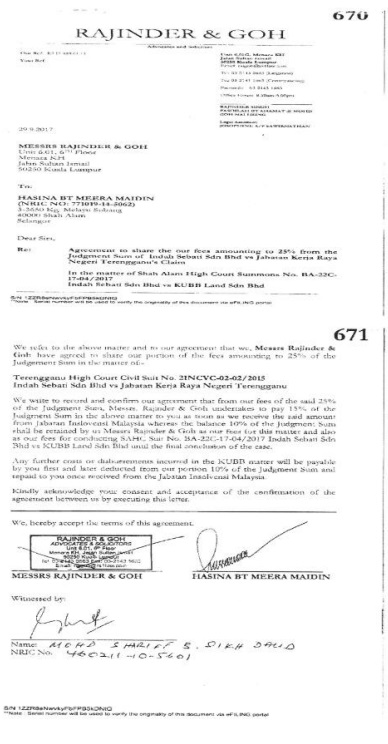

[11] The Agreement Letter can be perused below to appreciate its contents and determine the parties' consensus ad idem when it was executed. Two sets of the Agreement Letter were produced, including the stamped and unstamped copies.

What Transpired In The Trial

[12] PW1 - Hasina Meera Maidin (Appellant) claims there was a verbal undertaking in 2014 by Rajinder Singh to share 15% of the judgment sum. But she admits she was not present during the alleged 2014 verbal undertaking discussion. She also admits she was absent when the 29 September 2017 letter was signed. Further, she states that she paid RM80,000.00 legal fees progressively upon receiving invoices, and she agreed to pay because Rajinder (2nd Respondent) was willing to share a percentage of fees.

[13] PW2 - Jaafarul Shariff (Appellant's husband) confirmed a discussion with Rajinder Singh (2nd Respondent) in 2014 about claiming 15% from Indah Sebati as legal fees. He claims verbal agreement was made that 15% would be paid to his wife (Appellant) while admitting the RM80,000.00 as payment for legal fees for the cases.

[14] PW3 - Leonard D'Cruz is a lawyer friend of both Jaafarul (PW2) and Rajinder (2nd Respondent). He tried to mediate the dispute among parties in October 2019 but failed.

[15] DW1 - Goh Nai Hsing (3rd Respondent) is the partner in the law firm of the 1st Respondent. Her evidence supports the defence's position on threats and harassment.

[16] DW2 - Josephine Sawirnathan is the lawyer at the law firm (1st Respondent) where she spoke about the commotion and glass-breaking incident but admitted under cross-examination she was never threatened by the Appellant's husband (PW2).

[17] DW3 - Heryanti bt Nordin is the secretary at the law firm (1st Respondent), where she corroborated evidence about commotion but also admitted during cross-examination that she was never threatened.

[18] DW4 - Rajinder Singh (2nd Respondent) admits to signing the 29 September 2017 letter but claims it was under duress. He claims no verbal undertaking was given in 2014 and admits receiving RM80,000.00 fees from Plaintiff. After signing, he admitted he never took steps to revoke or dispute the Agreement Letter. He also did not make any police reports about alleged threats.

What The Trial Judge Decided

[19] The learned trial judge dismissed the Appellant's claim, finding that there was no evidence of a verbal agreement in 2014, that the Agreement Letter was signed under duress after threats and harassment, there was no valid consideration for the undertaking, and that the undertaking was void and unenforceable.

The Appeal

[20] Aggrieved, the Appellant eventually comes before me to have her claim re-tried through an appellate hearing. It is unfortunate for her to wait more than 3 years to have her appeal be heard and decided after the appeal notice was filed on 11 October 2021.

[21] The central issues embodied in the Amended memorandum of appeal dated 20 January 2022 are the following:

(i) On Evidence and Burden of Proof:

The Appellant argues that the trial judge erred in determining that they failed to prove their claim on the balance of probabilities, mainly regarding an oral undertaking mentioned in the Statement of Claim. The Appellant also argues that the judge's decision to set aside evidence (PW1) due to inconsistencies between positions taken in the Courts and to dismiss material facts about oral undertakings by the 1st and 2nd Respondents were wrong.

(ii) Financial Claims:

The trial judge failed to recognise that the Respondents are indebted to the Appellant based on an undertaking dated 29 September 2017, claiming entitlement to sums of RM658,684.07 and RM80,000.00. The Appellant argues that the Respondents' defence of unjust enrichment and lack of consideration were mere afterthoughts.

(iii) Legal Issues and Procedural Matters:

The Appellant contends that the judge erred in applying s 26 of the Contracts Act 1950 ("CA 1950") to the undertaking, arguing it was improperly deemed an agreement without consideration. It is also argued that the trial judge erred in invoking s 114(g) of the Evidence Act 1950 ("EA 1950") on the adverse inference to the Appellant in not calling a specific witness. The Appellant also argues that the trial judge erred in not considering that the Courts are not bound by the Legal Profession (Practice and Etiquette) Rules 1978.

(iv) Disputed Undertaking:

It is argued that the 29 September 2017 undertaking was voluntary (not coerced), created binding obligations that were breached, and that the Appellant, as a layperson, relied on the Respondents' special skill and knowledge regarding this undertaking.

Principle Of Appellate Intervention

[22] The jurisprudence on appellate review of factual findings in Malaysian courts can be summarised in three key principles: First, appellate courts should be hesitant to disturb findings of fact that depend on witness credibility. As established in China Airlines Ltd v. Maltran Air Corp Sdn Bhd & Another Appeal [1996] 1 MLRA 260, where the trial court's conclusions rely heavily on their direct observation of witnesses and assessment of their honesty and accuracy, appellate intervention is especially undesirable. Second, a distinction exists between two types of factual findings: those based on witness credibility versus those drawn from inference. According to China Airlines, appellate courts may more readily intervene in cases where the finding relies on inferences drawn from other facts rather than direct witness testimony. Third, "insufficient judicial appreciation of evidence" relates specifically to the trial judge's evaluation process. As articulated in Gan YookChin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1, a judge must properly assess and weigh all evidence presented, providing good reasons for accepting or rejecting any part of it.

[23] There is a high threshold for appellate intervention, requiring evidence of "serious misdirection" by the trial judge that renders the decision "plainly wrong." However, there are several established circumstances where intervention is warranted. The Federal Court in Gan Yook Chin (supra) established that "insufficient judicial appreciation of evidence" constitutes grounds for intervention when it aligns with the "plainly wrong" test. This focuses on how the trial judge evaluates evidence. Similarly, Ong Leong Chiou & Anor v. Keller (M) Sdn Bhd & Ors [2021] 4 MLRA 211 emphasized that appellate courts should intervene when decisions cannot be reasonably explained or justified, including findings that defy common sense. While Tengku Dato Ibrahim Petra Tengku Indra Petra v. Petra Perdana Berhad & Another Case [2018] 1 MLRA 263 stressed that mere disagreement with the trial judge's opinion is insufficient, misapplication of legal principles to factual findings may warrant intervention. Additionally, as highlighted in Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193, specific identification of the trial judge's failure to consider material evidence can justify intervention. The Sarmiina Sdn Bhd v. Gerry Ho & Ors [2023] 2 MLRA 599 case exemplifies proper grounds for appellate intervention. The trial judge failed to address key legal issues, consider statutory requirements, and properly evaluate evidence, resulting in a miscarriage of justice. Most significantly, intervention is warranted when the trial judge fails to consider both parties' defences, arguments and evidence, instead focusing only on one party's perspective.

[24] This Court must balance the need for judicial deference with the responsibility to correct serious errors in legal reasoning or evidence evaluation that result in plainly wrong decisions. Such failure by the trial judge to engage in this evaluation process may warrant appellate intervention. These principles establish a framework that generally favours deference to trial court findings while preserving the appellate court's ability to intervene when the trial judge's reasoning process is demonstrably flawed.

What The Trial Judge Concluded

[25] The trial judge determined these four key issues: whether the Respondents issued those undertakings vide the two letters dated 29 September 2017 for civil suits at the Terengganu High Court and Shah Alam High Court; whether the Appellant or her representatives forced, threatened and/or harassed the Respondents to obtain the undertaking letters; whether the Respondents owed the Appellant based on the undertakings and whether the Appellant suffered losses from breach of the undertaking terms; and whether the Appellant's claim amounts to unjust enrichment.

[26] Regarding the alleged verbal undertaking which led to the Agreement Letter, the trial judge found that the Appellant failed to prove her case. The evidence showed that the Appellant was absent during the alleged verbal undertaking discussion in 2014, contradicting her pleaded case. The failure to call Sharif as a witness despite his presence in court warranted an adverse inference under s 114(g) EA 1950. The trial judge also found that the RM80,000.00 paid by the Appellant was clearly for legal fees to commence ISSB's cases and not a consideration for any undertaking.

[27] As for the Agreement Letter, the trial judge found it to be an agreement and not an undertaking. The trial judge found no valid consideration for the agreement as required under s 26 CA 1950. The trial judge found that the 2nd Respondent was forced to sign the letter under duress due to threats and harassment from the Appellant's husband. This was corroborated by the testimonies of the Respondent's staff regarding incidents of commotion and threats at the office. Consequently, the judge held that the letter was invalid and had no legal effect.

[28] On losses and unjust enrichment, the trial judge concluded that since there was no valid agreement or undertaking, the Respondents did not owe any payment to the Appellant. Furthermore, the Appellant did not suffer any losses as she had already successfully claimed RM1,250,000.00 from ISSB in a separate suit. The trial judge found that the Appellant's claim amounted to unjust enrichment as she attempted to profit twice from the same matter, having already received returns of 6 times her original investment through the ISSB suit.

[29] Based on these findings, the Sessions Court dismissed the Plaintiff's claim with costs of RM10,000.00. The judge concluded that the Plaintiff had failed to prove her case on the balance of probabilities. In contrast, the Respondents proved their defence of duress and lack of consideration for the purported agreement.

Analysis Of The Appeal

1. The Written Agreement Created Valid Obligations

[30] The trial judge held that the Appellant failed to prove a verbal agreement made in 2014 between the Appellant and the 2nd Respondent that formed the basis of the 2nd Respondent signing the Agreement Letter. By such failure to prove, the trial judge held there was no such agreement as dictated in the terms of the Agreement Letter. I find the conclusion wrong because the Appellant need not prove the existence of the verbal agreement since it is proven through the Agreement Letter. Except for the allegation of no free consent by the Respondents, the contents of the Agreement Letter remain unchallenged. Section 10(1) CA 1950 expressly define agreements as contracts if made by the free consent of parties competent to contract, for a lawful consideration and with lawful object, and are not expressly declared to be void.

[31] The Agreement Letter is the ultimatum as it was entered by parties the latest after the purported verbal agreement in 2014, execution of the Warrant to Act dated 5 November 2014 and after the meeting held at the Respondents' office where the Agreement Letter was subsequently signed.

[32] Based on my analysis of this case, I find that the Agreement Letter is an outright agreement between the Appellant and the Respondents where inconsideration of the Appellant paying the RM80,000.00 legal fees for the Respondents' client ISSB for the two suits, the Respondents undertake to pay the Appellant 15% from the judgment sum they would eventually win in the two cases for their client ISSB.

[33] The trial judge erred in finding the Agreement Letter, a fee-sharing agreement, invalid for lack of consideration. The Agreement Letter represented a legitimate arrangement in which the Appellant agreed to pay costs upfront to enable the legal work to proceed in exchange for a share of the eventual recovery. This created binding obligations between the parties. The Agreement Letter specified the fee-sharing terms: 15% of any judgment amount to be paid to the Appellant for the advanced legal costs. The consideration is the payment by the Appellant of RM80,000.00 as upfront expenses to enable the legal proceedings. The Agreement Letter was properly witnessed and signed by both parties.

[34] The trial judge found no consideration when it was agreed that the Appellant had paid the Respondents vide the invoices the 1st Respondent issued to ISSB. This finding contradicts the facts and the law. Because the reciprocating act by the Respondents had yet to happen when the Appellant made the payments, the Agreement Letter stated the "undertaking" whereby the future conduct is for the Respondents to pay the Appellant the 15% out of the judgment sum to be received when the two cases concluded. It is a conditional contract subject to the realisation of the Judgment Sum when the two suits favour ISSB. In contrast, if no judgment sum is realised, the Appellant loses her payment for the legal fees of RM80,000.00 and cannot recoup her investment in ISSB. The Agreement Letter cannot become void.

[35] The application of s 26 CA 1950 was not made completely by the trial judge when the exceptions were not considered. Section 26 CA 1950 states:

"Section 26. Agreement without consideration, void, unless:

An agreement made without consideration is void, unless:

it is in writing and registered

(a) it is expressed in writing and registered under the law (if any) for the time being in force for the registration of such documents, and is made on account of natural love and affection between parties standing in a near relation to each other;

(b) it is a promise to compensate, wholly or in part, a person who has already voluntarily done something for the promisor, or something which the promisor was legally compellable to do; or

or is a promise to pay a debt barred by limitation law

(c) it is a promise, made in writing and signed by the person to be charged therewith, or by his agent generally or specially authorized in that behalf, to pay wholly or in part a debt of which the creditor might have enforced payment but for the law for the limitation of suits.

In any of these cases, such an agreement is a contract".

[36] Explanation 2 which is relevant in this case states:

"Explanation 2 - An agreement to which the consent of the promisor is freely given is not merely because the consideration is inadequate, but the inadequacy of the consideration may be taken into account by the court in determining the question whether the consent of the promisor was freely given".

[37] This position of the law is expounded on the inadequacy of consideration, which may also be relevant to whether a contract should be specifically performed. The Specific Relief Act 1950 ("SRA 1950") provides that specific performance of a contract cannot be enforced against a party to it if the consideration is so grossly inadequate either by itself or coupled with evidence of fraud or undue advantage taken (per Visu Sinnadurai in Contracts Act, A Commentary, 2015). In this case, the consideration was the legal fees paid by the Appellant to the Respondents. I stand guided by the judgment of the Federal Court in Halimah Abdul Rahman v. Fatimah Abdullah [1976] 1 MLRA 446 where the agreement there, among other things, states that:

"I, Fatimah admit to sell 'usaha saya' on the said land to Halimah for $300. The said sum mentioned I, Fatimah admit receiving from Halimah and I have handed possession of the said land to Halimah for her to enter and cultivate.

My agreement Fatimah with Halimah is that when the Government issue the documents of title on the said land then at that time, I, Fatimah undertake to transfer to Halimah and all expenses payable at the time I, Fatimah undertake to pay."

[38] Similarly, the Appellant intends to complete the Agreement Letter for the Respondents to complete the refused agreement. Fatimah pleaded uncertainty and no locus standi of Halimah of the land where the defence was the agreement is void because Halimah had no title. The Federal Court disagreed with the learned trial judge when Ali FJ expounded:

"My reading of this portion of the agreement is that the promise by the respondent, Fatimah, was to execute a transfer as and when she is issued with the document of title. On the promise the appellant, Halimah, paid the sum $300 which the respondent admitted to have received. In terms of paragraph (d) of s 2 of the Contracts Act 1950 the $300 was the consideration for the respondent's promise to execute a transfer. Also in terms of paragraph (e) of the same section the respondent's promise was the consideration for the $300. Having put it in this way, can there be any doubt that possession of the land was not the consideration of the agreement? Nor was it the object of the agreement for the object was to give the appellant something better than possession ie. Title."

[39] In this instant case, the same agreement would be the purported verbal agreement in 2014 that led to the execution of the Agreement Letter. Here, the parties went beyond the situation in the Halimah case as the agreement was documented and signed by the parties as per the Agreement Letter. By applying the judgment by Ali FJ above, the consideration is the RM80,000.00 paid by the Appellant as payment of the Respondents' fees for ISSB (being their client) for the Respondents' promise to pay the 15% from the Judgment Sum. The Respondents were contracted to pay as and when they were issued with the payment of the Judgment Sum. The Federal Court disagreed with the trial judge and held it was not void by s 10(1) CA 1950.

[40] It is trite that an undertaking falls under a typical contract requiring consideration. The Agreement Letter bears all hallmarks of a valid solicitor's undertaking as established in Nasir Kenzin & Tan v. Elegant Group Sdn Bhd [2008] 2 MLRA 628, namely that the Agreement Letter was issued on the Respondents' law firm letterhead, a solicitor signed in a professional capacity, it was worded in clear and unambiguous terms, and it was intended to rely upon.

[41] The solicitors' undertakings are enforceable even without consideration due to the professional obligations involved. As established in Re Choe Kuan Him Advocate & Solicitor; T Damodaran v. Choe Kuan Him [1976] 1 MLRA 118,undertakings given by solicitors in their professional capacity are enforceable to maintain public confidence in the profession. It is timely to be reminded of the judgment of Suffian LP in Re Choe Kuan Kim (supra) as expounded by the Appellant that echoes:

"The law and practice relating to solicitors' undertakings in Malaya in my opinion is the same as that in England.

Mr Choe is an officer of the court and we should compel him to honour undertakings by him promptly to secure public trust and confidence in the legal profession which is an ancient and honourable one, and the language used by MrChoe in this undertaking is clear, unambiguous and unqualified and that any one reading it cannot but get the impression that Mr Choe undertook to release the money in his hand the moment the lands had been transferred into the name of the Alor Merah Sdn Bhd or its assignees."

In the said case, Ali FJ stated:

"Such assurance coming from a solicitor, as it were, would leave the appellant in no doubt that it would be honoured once the transfers were completed. But the respondent did not honour his words or undertaking. He tried to put up all sorts of excuses for not doing so."

[42] What more when the solicitor's undertaking was given with consideration. The case emphasises solicitors' undertakings must be honoured to maintain public trust. As held in Semenda Sdn Bhd & Anor v. CD Anugerah Sdn Bhd & Anor [2010] 2 MLRA 328, undertakings are fundamental to legal practice, and breaching them undermines confidence in the profession.

[43] PW1 (Appellant) testified the legal fees were paid progressively upon receiving the invoices from the 1st Respondent. DW4 (2nd Respondent) agreed that the Appellant paid all legal fees, which, in total, RM80,000.00 was paid for handling both suits. PW1 said:

On Why Fees are Paid:

HASINA: Dia berjanji sebab saya membawa kes Indah Sebati kepada peguam ini, dengan bersetuju membayar yuran guaman awal. Sebagai return, lawyer Rajinder berjanji untuk memberi saya 15% .

About Payment of Fees:

HASINA: No, I just follow the bills. Whenever they send me the invoice, they ask for the payment, then I just release.

VB: So, the fee guaman, Puan, was paid progressively?

HASINA: Yes. Progressively.

On Knowledge of Payment:

RAJINDER: Sekitar tarikh e-mel tersebut Puan Hakim. Saya telah pun memberitahu kawan karib dia Leonard D'Cruz, pagi sebelum mereka hadir kat pejabat saya. Dalam recording itu memang tertera. Saya beritahu Jaafarul dan isteri, isteri dia. Saya dah pun beritahu dia, Leonard D'Cruz, yang saya dah terima duitnya.

[44] During the trial, DW4 (2nd Respondent) admitted to preparing and signing the undertaking on the 1st Respondent's letterhead, admitted instructing his staff Christina to type the undertaking, admitted he "was ready to agree" to give the undertaking but failed to produce any "draft" document that Appellant's husband allegedly brought to the law firm. The highlights of DW4's testimony areas follows:

DW4's Admissions About Undertaking:

SV: Do you see the signatures there in pp 31 and 33?

RAJINDER: Yes.

SV: And the signatures you signed today?

RAJINDER: Yes.

SV: I put it to you these are your signatures.

RAJINDER: Agree.

S V: And in p 31, the Rajinder and Goh company chop as well as p 33 is from your law firm.

RAJINDER: Agree.

On Preparing the Undertaking:

SV: Alright. You then instructed Christina to go ahead and type the letter.

RAJINDER: Yes

SV: And I put it to you Christina typed the letter after you instructed her or told her to type the letter

RAJINDER: Yes.

SV: I take you to p 35, B1 and you confirm you signed and issued this letter on 9 October 2017?

RAJINDER: Yes.

SV: And you wrote this to Pn Haslina, the Plaintiff?

RAJINDER: Yes.

On Understanding Terms of Undertaking:

SV: Can you also see the further paragraph, the second last paragraph, the same 31, that the word 'any further cost or disbursements incurred will be payable by you first and later deducted from our portion of the 10% of the judgment sum repaid to you.' So, that paragraph says, in plain ordinary reading, that from the judgment sum that you received, 10% is due to the law firm?

RAJINDER: Agree.

SV: Thank you. And you also agree to the entire sentence that finishes, 'and repaid to you once received from the Jabatan Insolvensi Department.' You agree to the whole sentence, following the 10%?

RAJINDER: Agree

[45] Evidence of the post-undertaking conduct showed DW4 continued normal business relations after the undertaking. On 9 October 2017, DW4 was still in regular contact with the Appellant and never took steps to retract, revoke or cancel the undertaking. DW4 also never lodged a police report despite claiming serious threats nor disputing or correcting the Appellant's letter of 30 August 2018. The letter stated the Appellant's forwarded documents as requested by DW4 for purposes of submission to the Insolvency Department to claim the 25% proceeds and thereafter make payment of 15% to the Appellant as agreed financing and assistance fee. The letter was received unequivocally by the Respondents on the same day.

On No Response to 30 August 2018 Letter:

SV: Do you have a reply to this letter? If you have, please show us.

RAJINDER: Tidak ada Puan Hakim.

[46] DW4 also admitted to being old friends with the Appellant's husband and going back more than 10 years. This explains why the ISSB cases were referred to him:

RAJINDER: The Plaintiff's husband and I are friends from a long time ago.

RAJINDER: At least more than 10 years. Lebih daripada 10 tahun, Puan Hakim.

[47] The referred case by the Respondents, Malaysia British Assurance Bhd v. Sihazko Sdn Bhd & Ors [2004] 2 MLRH 612 is a reflection of the Halimah case above where In Sihazko case (supra), the executed letters of indemnity by the defendants were made based on the plaintiff's undertaking tissue the insurance guarantee which guarantee was issued. This undertaking or promise by the plaintiff must be construed as good consideration under s 2 CA 1950. In this case, the Appellant paid the fees on the Respondents' undertaking to release part of the Judgment Sum to the Appellant once they managed to secure the Judgment Sum. The Judgment Sum was secured when ISSB won the two suits. Therefore, the Respondents must fulfil their promise to give the Appellant her agreed portion of the Judgment Sum received. The issue of nudum pactum (naked orbare promise) under the common law where a promise that is not legally enforceable for want of consideration is without merits as there is consideration respectively from the Appellant of the payment of fees to the Respondents and from the Respondents of the undertaking to release part of the Judgment Sum to her (following First National Bank of Chicago v. Lam Thoo Sang & Ors [1978] 1 MLRH 548).

[48] What I understand from the Respondents' argument is that because the trial judge found the Agreement Letter to be void as it was issued without the 2nd Respondent's free consent, there is no consideration. This argument differs from what was in her grounds of judgment, where the Appellant's case was dismissed because she failed to prove the verbal undertaking in 2014,which led to the Agreement Letter becoming void. The trial judge did not decide whether there was consideration but concluded the Agreement Letter was void due to the failure to prove the verbal undertaking. The trial judge should consider whether there is consideration or not to determine if the Agreement Letter is a binding contract. The focus on proof of the verbal undertaking in 2014 is misconstrued when the objective is to ascertain whether the Agreement Letter is enforceable or not. Analysis should be done on the parties' actions after the execution of the Agreement Letter to determine the existence of compliance to the terms contained therein.

[49] The trial judge also accepted the Respondents' evidence of no free consent when the Agreement Letter was executed, where the trial judge found there was coercion, oppression and threats inflicted on the Respondents. Thus, the trial judge held the Agreement Letter was unlawfully executed where it was held to be void and unenforceable. I find the trial judge's decision on the issue of no consent is unsubstantiated by all of the evidence presented, particularly when the 3rd Respondent did not know about the Agreement Letter and there is only hearsay evidence on the coercion, oppression and threats purported.

2. No Evidence of Coercion

[50] While the trial judge found the Agreement Letter was obtained through coercion, the evidence presented does not support this conclusion. The allegations of threats and disturbances were based mainly on hearsay testimony. The Respondents did not produce police reports or other direct evidence to substantiate their claims of harassment and coercion. The allegations of coercion were based on the testimony from DW2 and DW3, who admitted they did not directly witness the alleged incidents. No police reports were filed regarding the alleged threats and disturbances. The Respondents also failed to provide any corroborating evidence of threats or coercion. I find that the failure to file any police report is fatal to the Respondents' allegation of threats or coercion against the Appellant as it can be construed as a bare allegation (see Soo Lip Hong v. Tee Kim Huan [2005] 1 MLRA 801). In Paldraman Palaniappan & Ors v. Lachemi Sanganayar [1992] 2 MLRH 221, the judgment by Mahadev Shankar J must be noted:

"In all the circumstances of this case and in the light of this letter Consider the defendant's bare allegation that she was defrauded into executing the statutory declaration and the application to transfer inherently incredible and totally unworthy of belief. There was no police report, and there was absolutely no action taken to establish the alleged forging even though the defendant was then being legally advised."

[51] DW2 (Josophin) testified under cross-examination that the Appellant or her family never threatened her. DW3 (Heriyanti) confirmed no threats were made against her. The Respondents' only evidence about alleged threats was hearsay from "Glory", who was never called as a witness:

SV: Ok, alright. So, now I put it to you, Puan Hasina atau Jaafarul atau father in-law did not threaten or raise their voice with you, Pn Josophine.

JOSOPHIN: Tidak.

SV: No, yes?

JOSOPHIN: Tak ada.

SV: Yes, yes, I know, yes, ada. Saya cadangkan, Puan, pada bila-bila masa, Plaintif atau Jaafarul atau bapa dia they never threatened you, Gloria or Ms Josophine. They never threaten or raise their voice, shout at any of the staff, setuju?

HERI: Setuju.

SV: Correct. In fact, my instructions are they have seen you a number of times, and they were very pleasant with you. Do you agree with that? They said hello, they wished you.

JOSOPHIN: Ya.

[52] The Respondents claiming no consent bear the burden to prove there was coercion, oppression and threats inflicted on the Respondents (as in s 101 EA 1950), and when there is no evidence as such, the burden is not discharged (s 102 EA 1950). All of the Respondents' witnesses gave hearsay evidence. The witnesses knew the shouting and glass breaking in the meeting room from the Respondents' receptionist named Glory. She was not called as a witness despite she has first-hand knowledge of the incident. DW1, DW2 and DW3 evidence is all hearsay that falls on the hearsay principle mentioned in the Respondents' referred case of Leong Hoong Khie v. PP & Another Case [1984] 1 MLRA 599:

"The general rule Is that hearsay evidence is not admissible as proof of a fact which has been stated by a third person. This rule has been long established as a fundamental principle of the law of evidence. To quote Lord Normand in Teper v. R:

"The rule against the admission of hearsay evidence is fundamental. It is not the best evidence, and it is not delivered on oath. The truthfulness and accuracy of the person whose words are spoken by another witness cannot be tested by cross-examination, and the light which his demeanour would throw on his testimony is lost.".

In our opinion, another reason is the danger that hearsay evidence may be concocted, fabricated and tailored to suit the witness's testimony."

[53] DW1 admitted not to be in the meeting room when the 2nd Respondent signed the Agreement Letter. DW1 did not even know about the Agreement Letter until the document was filed in court, and she also admitted since the Agreement Letter bore the 1st Respondent's letterhead, the Respondents would need to be liable as well.

GOH: I mean, I first read this letter after I got this, when I received the bundle lah, when we got the summons, then only I read everything.

HS: Did you see the letter before that?

GOH: No.

HS: Who prepared this letter?

GOH: I mean I not sure.

SV:

................

HAKIM: ...........Let the witness explain.

GOH: I am not sure but they used our letterhead lah.

HS: So, what do you mean by 'commits'?

GOH: I mean, it's used by our letterhead. If this is true, I mean, we will, I Will need to be liable as well.

HS: If this is true?

GOH: Yes.

[54] The oral evidence that the Respondents were threatened or coerced by the Appellant, Jaafarul, or her father at the law firm was never substantiated by any facts (s 59 EA 1950), which requires oral evidence to be direct (s 60 EA 1950). There was no such threat or coercion.

3. Professional Rules Considerations

[55] The trial judge failed to properly consider that fee-sharing arrangements between solicitors and referring parties when properly structured and disclosed, can be legitimate under professional conduct rules. The agreement here appears to have been transparent about the fee-sharing terms. The Agreement Letter involved legitimate legal proceedings in the two suits. The fee-sharing terms were translated into a written document that was agreed upon by both parties.

[56] Such arrangements can promote access to justice by allowing parties to obtain legal representation that they may otherwise be unable to afford. The trial judge's rejection of the Agreement Letter without considering its legitimate purpose was an error in law and fact. Evidence showed that ISSB required assistance with funding to pursue legitimate legal claims. The RM80,000.00 advanced by the Appellant enabled the litigation to proceed. The successful litigation resulted in a judgment of RM1.25 million.

4. Unjust Enrichment

[57] The trial judge's finding of unjust enrichment was misplaced. In the grounds of judgment (para 72), the fact that the Appellant invested in ISSB and that the award given to the Appellant by the High Court was very high should not be considered (see ss 6 and 7 EA 1950 on the relevancy of facts). This case concerns the Agreement Letter, which the trial judge had rightly found to be an agreement, not an undertaking. It does not matter what history the Appellant had with ISSB because this action only concerns the Agreement Letter. It was prejudicial to the Appellant when the trial judge considered irrelevant facts.

[58] The Respondents pointed out that only part of the cross-examination of the Appellant and the other part and her re-examination need to be produced for completeness of testimony (see Encl 44 pp 202 & 216-217 and 366-367):

HS: And you're still claiming another RM600,000.00 now.

HASINA: This is for another agreement.

HS: You're claiming RM600,000.00. Yes?

HASINA: Yes.

HS: So now that you want this honorable Court to give you is basically tosay anybody can now go to lawyers, make them sign something like this, come out with little bit of money because they were scare the are going to lose their investment and then when the judgment comes in your favour you try to sapu everything.

HASINA: No. I disagree with this.

HS: So what is he sharing with you?

HASINA: His fees amounting-

HS: His fees. And his fees is from the judgment sum.

HASINA: Yes.

GP: So you have the judgment-

HASINA: Yes.

GP: On the claim for 50%.

HASINA: Yes.

GP: Of the profit-sharing?

HASINA: Yes.

GP: Now we come to this case, now in this case, what are you claiming?

HASINA: I'm claiming 15% from the agreement between me and Rajinder, Mr Rajinder.

GP: May I ask you this, are you making a double claim in this suit and the other suit, Suit 511?

HASINA: No.

[59] The first line of defence falls because Judgment Sum that the Respondents agreed to pay 15% to the Appellant does not belong to the Respondents. What that does not belong to one cannot be claimed. One has suffered losses, and the other reaped unjust enrichment. The Federal Court case referred by the Respondents detailed the laws on unjust enrichment where it is clear that this case is not a case on unjust enrichment. Dream Property Sdn Bhd v. Atlas Housing Sdn Bhd [2015] 2 MLRA 247 established that unjust enrichment represents a distinct cause of action, while restitution serves as the remedy. The court positioned unjust enrichment as an independent source of rights and obligations in private law, equal in standing to contract and tort law, rather than being subsumed within either category. Four mandatory elements must be proven: the plaintiff must have been enriched, this enrichment must have occurred at the defendant's expense, the retention of the benefit must be unjust, and there must be no available defences that would eliminate or reduce the plaintiff's liability. These elements form the basic analytical framework for evaluating unjust enrichment claims The Federal Court then explored two competing approaches for determining whether enrichment is "unjust" − the English approach, which looks for specific unjust factors such as mistake or failure of consideration, and the civilian approach, which examines whether there is a lack of legal basis for the enrichment. The court ultimately adopted the civilian "absence of basis" approach, reasoning it would lead to fairer outcomes. Under this approach, a plaintiff can escape restitutionary liability only by demonstrating legal grounds (from legislation or contract) for receiving the benefit. The remedial focus of unjust enrichment is unlike compensation, which focuses on the claimant's loss, whereas unjust enrichment remedies are gain-based. The measure is not what the claimant lost but rather the value of the benefit received by the defendant that needs to be reversed. This distinguishes unjust enrichment remedies from traditional compensatory damages.

[60] The Appellant provided proof of the advance payment of legal costs, which enabled the litigation to proceed. Allowing the Respondents to retain the full benefit after accepting those payments would create an unjust enrichment. The Respondents benefited from the RM80,000.00 advanced costs. Evidence showed the Appellant's contribution directly enabled the successful litigation. The Appellant had fulfilled her obligations under the Agreement Letter. The Respondents benefited from the funding but sought to avoid their agreed contractual obligations.

[61] The Respondents argued that the Agreement Letter was prohibited by law to share fees that it is caught under ss 24(a) and (e) CA 1950 where the consideration becomes unlawful by it contravening s 37 of the Legal Profession Act 1976 ("LPA 1976") and r 52 of the Legal Profession (Practice and Etiquette) Rules 1978 ("LPPE Rules 1978"). It is also argued that the Agreement Letter opposes the public policy to prohibit against touting arrangements.

[62] Section 24(a) and (e) CA 1950 states:

"Section 24. What considerations and object are lawful, and what not.

The consideration or object of an agreement is lawful, unless:

(a) it is forbidden by a law;

...

(e) the court regards it as immoral, or opposed to public policy".

[63] While s 37 Legal Profession Act 1976 and r 52 Legal Profession (Practice and Etiquette) Rules 1978 state:

"Legal Profession Act 1976

No unauthorized person to act as advocate and solicitor

37.(1) Any unauthorized person who:

(a) acts as an advocate and solicitor or agent for any party to proceedings or in any capacity, other than as a party to an action in which heis himself a party, sues out any writ, summons or process, or commences, carries on, solicits or defends any action, suit or other proceedings in the name of another person in any of the Courts in Malaysia or draws or prepares any instrument relating to any proceedings in any such Courts; or

(b) will fully or falsely pretends to be, or takes or uses any name, title, addition or description implying that he so duly qualified or authorized to act as an advocate and solicitor, or that he is recognized by law as so qualified or authorized, shall be guilty of an offence and shall on conviction be liable to a fine not exceeding two thousand five hundred ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to both.

(2) Without prejudice to the generality of subsection (1), any unauthorized person who either directly or indirectly:

(a) draws or prepares any document or instrument relating to any immovable property or to any legal proceedings or to any trust; or

(b) takes instructions for or draws or prepares on which to found or oppose a grant or probate or letters of administration; or

(d) on behalf of a claimant or person alleging himself to have a claim to a legal right writes publishers or sends a letter or notice threatening legal proceedings other than a letter or notice that the matter will be handed to an advocate and solicitor for legal proceedings; or

(e) solicits the right to negotiate, or negotiate in any way for the settlement of, or settles, any claim arising out of personal injury or death and founded upon a legal right or otherwise, shall, unless he proves that the act was not done for or in expectation of any fee, gain or reward, be guilty of an offence under this subsection.

(3) Any unauthorized person who offers or agrees to place at the disposal of any other person the services of an advocate of any fee, gain or reward, be guilty of an offence under this subsection:

Provided that this subsection shall not apply to any person who offers or agrees to place at the disposal of any other person the services of an advocate and solicitor pursuant to a lawful contract of indemnity or insurance.

(4) Every person who is convicted of an offence under subsection (2) or(3) shall, on conviction, be liable for the first offence to a fine not exceeding five hundred ringgit or in default of payment to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months and for the second or subsequent offence to a fine not exceeding two thousand ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to both.

(5) Any act done by a body corporate which if done by a person would be an offence under subsection (1), (2) or (3) or is of the nature or in the manner as to be calculated to imply that the body corporate is qualified, or recognized bylaw as qualified, to act as an advocate and solicitor shall be an offence under this section and the body corporate shall, on conviction, be liable for the first offence to a fine not exceeding one thousand ringgit and for the second or subsequent offence to a fine not exceeding three thousand ringgit and where the act is done by a director, officer or servant thereof the director, officer or servant shall, without prejudice to the liability of the body corporate, be liable to the punishment provided in subsection (4).

(6) Where any firm does an act which if done by a person would be an offence under subsection (1), (2) or (3) every member of the firm shall be deemed to have committed the offence unless he proves that he was unaware of its commission.

(7) Any person who does any act in relation to a contemplated or instituted proceeding in High Court which act is an offence under this section shall also be guilty of a contempt of the Court in which the proceeding is contemplated or instituted and may be punished accordingly irrespective of whether he is prosecuted for the offence or not.

Legal Profession (Practice And Etiquette) Rules 1978

No Division of costs or profits with unqualified person

52. It is unprofessional and improper conduct-

(a) for an advocate and solicitor to divide or agree to divide either costs received or the profits of his business with any unqualified person;

(b) for an advocate and solicitor to pay, give, agree to pay or agree to give any commission, gratuity or valuable consideration to any unqualified person to procure or influence or for having procured or influenced any legal business and whether such payment, gift or agreement be made under pretext of services rendered or otherwise, but his rule does not prohibit the payment of ordinary bonuses to staff;

(c) for an advocate and solicitor to accept or agree to accept less than the scale fees laid down by law in respect of non-contentious business carried out by him except for some special reason where no charge at all is made".

[64] Legal dictionaries primarily define 'Touting' as looking out for custom in an obtrusive, aggressive, or brazen way or attempting to sell something through direct or persistent approaches. This basic definition forms the foundation for more specific legal interpretations.

[65] The courts have expanded this definition to encompass specific behaviours in the legal profession. Touting occurs when financial arrangements are made for client procurement, mainly when non-lawyers receive commissions from law firms for securing clients. The courts have emphasised that touting can occur whether done directly or indirectly and whether conducted by lawyers or non-lawyers.

[66] In Koid Hong Keat v. Rhina Bhar [1989] 1 MLRH 766, the High Court established that touting arrangements are fundamentally unlawful and against public policy. It determined that agreements between solicitors and touts for client referrals are unenforceable, particularly when they involve fee-sharing with unqualified persons. This definition was further refined in Balakrishnan Devaraj v. Patwant Singh Niranjan Singh & Anor [2004] 3 MLRH 235. The High Court examined the LPPE Rules 1978 in detail, confirming that touting encompasses direct and indirect client procurement methods for reward. It reinforced that such arrangements cannot form valid contractual relationships, regardless of how they are structured or presented. In Lee Kuang Guat v. Chiang Woei Chien [2020] MLRAU 335, the Court of Appeal explicitly recognises touting as a menace to the legal profession. The Malaysian Bar's press release dated 27 August 2019 defined 'touts' as individuals who receive commissions from law firms for securing clients. The judgment emphasises the continuing public policy concerns against touting practices and reaffirms the profession's stance against such arrangements.

[67] The definition in r 51 LPPE Rules 1978 prohibits advocates and solicitors from engaging in any activity that constitutes touting, whether directly or indirectly. The courts have consistently held that touting arrangements is fundamentally against public policy and professional ethics. This includes any system where intermediaries are paid to influence a client's choice of legal representation or where there are monetary incentives for client referrals. The courts distinguish between legitimate professional arrangements and touting. While fee-sharing between qualified legal professionals for legitimate services may be permissible, arrangements specifically designed to procure clients through intermediaries are considered touting. This distinction helps maintain professional standards while allowing legitimate business relationships within the legal community.

[68] Bar Malaysia v. Index Continent Sdn Bhd [2016] 1 MLRA 559 reinforced the Bar Council's regulatory powers in protecting the public interest in legal matters. The court confirmed that the Bar Council has concurrent jurisdiction with the Attorney General regarding legal practice matters. It emphasised that powers under the Legal Profession Act should be interpreted purposively to enable the Bar Council to fulfil its role in protecting the public interest. This judgment strengthened the Bar's authority to take action against unauthorised practices and maintain professional standards.

[69] These judgments collectively reinforce the principle that professional obligations arise from formal arrangements, conduct, and implied relationships. They establish that the duty of care owed to clients exists regardless of formalities and that the legal profession's regulatory bodies have broad powers to protect both public interest and professional standards.

[70] I find that the arrangement between the Appellant and the Respondents is a legitimate professional arrangement between the law firm, including its partners, and the company's investor. A careful examination of the nature of the arrangement between the parties that led to the arrangement dictated by the Agreement Letter showed it is not touting. Somewhat, the Appellant contracted with the Respondents as the investor of ISSB, and she wanted to recoup her investment previously made.

[71] The evidence shows that the Appellant did introduce ISSB to the Respondents. The Appellant testified she "recommended the lawyer to ISSB's representative." This was corroborated by DW4's admission during cross-examination that "Plaintiff was an investor in Indah Sebati and had referred the Indah Sebati cases to the 1st and 2nd defendants to handle Indah Sebati's claims in the Terengganu and Shah Alam High Courts."

[72] However, mere client introduction to a law firm does not ipso facto amount to touting. Drawing guidance from Balakrishnan Devaraj v. Patwant Singh (supra), touting specifically involves arrangements where fees or commissions are shared purely in exchange for bringing clients to the firm. The relationship must be examined holistically. The factors distinguishing this case from pure touting arrangements are as follows. First, the Appellant was an investor in ISSB with a legitimate interest in the litigation outcome. Second, she paid RM80,000.00 in legal fees to enable the cases to proceed when ISSB lacked funds. Third, her role encompassed financing and facilitating the litigation, extending well beyond client referral. The subsequent undertaking for 15% of the judgment sum must be viewed in the context of her financial contribution and legitimate business interest rather than as a commission for the referral. This materially differs from Balakrishnan's case, where the agreement was purely to receive a 25% commission for referring accident cases without any other legitimate interest in the litigation.

[73] The LPPE Rules 1978 aim to prohibit arrangements where intermediaries profit solely from referring clients without any legitimate connection to the litigation. The Rules do not prohibit legitimate business arrangements where client introduction is incidental to substantive involvement in financing and facilitating litigation. The Appellant's introduction of ISSB to the Respondents formed part of a broader legitimate business arrangement stemming from her position as investor and financier. The subsequent undertaking was grounded in these legitimate interests rather than being payment for touting. The relationship between the parties extended well beyond mere client referral for commission, grounded in the Appellant's legitimate role as investor and financier of the litigation.

[74] This case resonates with Bhavanash Sharma Gurchan Singh Sharma (mengamal Di Bawah Nama Dan Gaya Bhavanash Sharma ) v. Jagmohan Singh Sandhu [2021] MLRHU 1150, where it dealt with fee-sharing arrangements in successful litigation. The High Court upheld an agreement to share 10% of settlement proceeds between lawyers as valid, distinguishing it from touting arrangements. The case emphasised that agreements between qualified legal professionals for legitimate services are enforceable, unlike arrangements with non-lawyers for client procurement. The Court also referenced the Malaysian Bar's position that touting is "abhorrent to the legal profession and detrimental to the public interest."

[75] From my analysis, the fee-sharing, in this case, is in the context of third-party litigation funding (TPLF), which refers to an arrangement where the litigation funder receives a portion of the legal fees or damages awarded in a successful case. In essence, fee-sharing in TPLF involves the funder receiving a predetermined percentage of a case's financial outcome in exchange for funding the litigation costs upfront. The litigation funder commonly receives 15-40% of awards, depending on the funding arrangement. TPLF allows law firms to return to their preferred billable hour model, with the funder paying the law firm's fees and then recouping their investment (plus profit) from a successful outcome.

[76] The Agreement Letter shows that the funder (Appellant) would receive 15% of the judgment sum from a particular case. It shows how to share the legal fees payable to the law firm and, after that, payable to them with the Appellant (the party that arranged the funding). The Agreement Letter concerns the working ethics related to fee-sharing arrangements between lawyers and non-lawyers, which is generally prohibited in many jurisdictions but is a key aspect of how TPLF operates.

[77] Ramalingam S (2023), in her article on legal funding in Malaysia and solicitors' undertakings, provide important context for reconsidering this appeal. The article highlights that access to justice remains a significant challenge in Malaysia's civil litigation system, with limited legal aid options. This broader context is relevant when considering arrangements that may facilitate access to justice, even if they push the boundaries of traditional fee structures.

[78] The UK, Australia, and the US courts generally accept TPLF while Canadian courts have been more cautious. Sarma R (2022) wrote that if there is no corruption of justice, champerty and maintenance should not stand in the way of TPLF. It recommends addressing adverse costs, ethical concerns, and control over lawsuits through comprehensive rules and regulations to protect vulnerable clients while promoting funders' interests. The writer argues for a more nuanced approach to TPLF, focusing on its potential to increase access to justice rather than outdated concerns about champerty and maintenance. Champerty and maintenance are legal doctrines that historically prohibited certain forms of litigation support. They are ancient legal doctrines initially developed to prevent corruption in the justice system. Champerty is a specific form of maintenance where the person supporting the lawsuit does so in exchange for a share of the proceeds if the case is successful. Maintenance refers to supporting someone else's lawsuit, typically by providing financial assistance.

[79] A separate point I find is that the fees received by the Respondents have become their money, namely, income for the law firm. The Respondents have the right to deal with their income where, in this case, they had agreed to pay the Appellant such fees amounting to 15% of the judgment sum in the two suits.

[80] Payments made by the Appellant would go into the 1st Respondent's client account, where the money may be drawn from the client's account. According to the Solicitors' Account Rules 1990 ("SAR 1990") RO, the paid fees received by the Office for or towards payment of the Respondents' costs where a bill of costs (such as the invoice issued by the law firm) or other written intimation of the amount of the expenses incurred has been delivered to the client and the client has been notified that money held for him will be applied towards or in satisfaction of such costs (r 7 SAR 1990).

[81] The fees stated in the Agreement Letters fall under the definition of "costs" in the LPA 1976, which includes fees, charges, disbursements, expenses, and remuneration. In this case, the fees received by the Respondents from the Appellant have become their money, and the Respondents are at liberty to deal with the money in whatever manner they intend to. The Respondents dealt with part of their fees by sharing their portion of 15% of the judgment sum in the two suits to be paid to the Appellant as stipulated in the Agreement Letter. Both parties reached a consensus by signing the Agreement Letter, and they acted on the terms contained. The Appellant is entitled to what the Respondents promised her.

Decision

[82] For the reasons above, I allow the appeal with costs. The Sessions Court decision is set aside, and judgment is entered for the Appellant as prayed for in the claim, namely for the 15% of the judgment sum amounting to RM658,684.07; return of legal fees of RM80,000.00 and interest at 5% per annum from the date of judgment until full realisation.

[83] The Appellant's claim for the return of the RM80,000.00 legal fees is found in the Agreement Letter where the express undertaking by the Respondents stating: "Any further costs or disbursements incurred in the KUBB matter will be payable by you first and later deducted from our portion 10% of the Judgment Sum and repaid to you once received from the Jabatan Insolvensi Malaysia."

[84] The fees were paid to enable the JKR suit to proceed when ISSB lacked funds. This was acknowledged by DW4 who testified that "Indah Sebati dah lepas tangan" and without the Appellant's payment of fees, the cases could not have proceeded. The condition triggering the obligation to return these fees has been met. The evidence shows that the Jabatan Insolvensi Malaysia ("JIM") paid the Respondents on 27 August 2019. This payment satisfied the condition specified in the undertaking for the return of the fees. Therefore, the Appellant's entitlement to the return of RM80,000.00 is proven by the express written undertaking to return the fees, the payment of these fees by the Appellant, fulfilment of the condition triggering the return obligation and proof of payment and receipt of funds from the Insolvency Department.

[85] This claim stands regarding the Respondents' undertaking's validity as it represents actual funds paid by the Appellant for which a clear promise of return was made and the conditions for return have been satisfied.