Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Kamaluddin Mohd Said, Hashim Hamzah, Wong Kian Kheong JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: J-01(NCvC)(W)-275-05-2021]

30 July 2025

Tort: Negligence — Medical negligence — Appeal against High Court's decision on liability and quantum of damages — Whether respondent's pre-existing health problem should have been considered in respect of liability and quantum — Whether egg-shell skull rule applied in medical negligence cases, and if so, to what extent — Whether negligence of 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants materially contributed to respondent's brain damage — Whether High Court erred in not dismissing claim against the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th appellants in absence of evidence — Whether 17th appellant vicariously liable for employees' negligence and directly liable for breach of contract — Whether certain awards were "so extremely high" as to warrant appellate intervention

The respondent was pregnant with her second child and was referred to Hospital Sultanah Aminah, Johor Bahru ("hospital") on 11 November 2013. At the time, the foetus was at about 33 weeks of gestation. The respondent was diagnosed with Placenta Praevia Type 3 Posterior ("PP Type 3 Posterior") and was scheduled for an elective Caesarean section ("C-section") on 16 December 2013. While waiting for the elective C-section, the respondent was warded at the hospital for rest and monitoring. On 12 December 2013, the respondent had contraction pains and underwent an emergency C-section under general anaesthesia. Soon after delivery of the child, the respondent became bradycardic, and the oxygen saturation and capnograph were not recordable. The respondent then developed pulseless electrical activity, for which cardiopulmonary resuscitation was administered, and after 5 minutes, there was a return of spontaneous circulation. The respondent was diagnosed with amniotic fluid embolism ("AFE") and subsequently developed bleeding from the vagina and puncture sites, suffered blood loss, and was given a blood transfusion. The respondent was transferred to the intensive care unit ("ICU") for treatment and subsequently suffered severe and irreversible brain damage. The respondent was discharged from the hospital on 3 April 2014 after her rehabilitation period. The respondent, through her husband and litigation representative, Khairil Faiz Rahamat ("PW5"), sued the doctors and nurses at the hospital, ie the 1st to 16th appellants, who were involved in her C-section, treatment, and management, for medical negligence. The respondent's claim against the 17th appellant, which owned and managed the hospital, was for a breach of contract between her and the 17th appellant, and for being vicariously liable for the acts of the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants, who were its employees.

The instant case concerned whether the appellants had breached their duty of care to the respondent in respect of the C-section performed on the respondent and the subsequent treatment of the respondent in the ICU. The High Court found, inter alia, that the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants were liable to the respondent for the tort of medical negligence; that the sessional intensivist ("DW5") who was involved in the treatment and management of the respondent, although not an employee of the 17th appellant, was liable for medical negligence; and that the 17th appellant was vicariously liable for the acts of the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants and for breach of contract with regard to its 'organisational and system failures'. The High Court accordingly awarded damages for the various items of special and general damages in favour of the respondent, together with interest and costs. Hence, the instant appeal by the appellants against the High Court's decision on liability and quantum of damages. The appellants submitted, inter alia, that at the material time of the respondent's admission to the hospital, she was already a high-risk patient with a pre-existing health problem, namely, PP Type 3 Posterior, which had contributed to and/or worsened her brain damage and hence, the appellants' liability should be either totally or partially excluded; that the High Court should have recognised that AFE was a rare occurrence for which there was no universally accepted diagnostic criteria and standard treatment protocol; that the respondent's brain damage was due to AFE and, therefore, the appellants should not be held liable for medical negligence; and given the factual finding of negligence of the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants, the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th appellants' appeal should be allowed on this ground alone. As regards the quantum of damages, it was submitted that the High Court should have applied an 'Evidence-based Medicine' approach in deciding the quantum issue and should only award a reasonable amount of damages. The respondent, however, submitted, inter alia, that in accordance with the egg-shell skull rule, the appellants should have accepted her as she was at the time of her admission to the hospital; and that the High Court's decision on liability and quantum should be upheld.

Held (allowing the appeal in part; quantum of damages varied; and ordered accordingly):

(1) The nature and extent of a doctor's duty of care might depend on, inter alia, the patient's pre-existing medical problem and/or vulnerability, and in deciding whether the doctor's duty of care had been breached, the court might take into account the patient's pre-existing medical problem and/or vulnerability. Where there was a breach of such duty, the burden would be on the respondent to prove on a balance of probabilities that the breach had materially contributed to the patient's death, injury, damage, and/or loss. If there had been an exacerbation of the patient's pre-existing medical problem, the egg-shell skull rule could apply, and the doctor would be liable for the said exacerbation. If, however, the exacerbation was part of the patient's death, injury, damage or loss, there could not be double recovery by the patient for the said exacerbation, and the patient's death/injury, damage, and loss. There was no room to invoke the egg-shell skull rule if the pre-existing medical problem was not worsened by the doctor's breach of duty of care. (para 23)

(2) Premised on Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng (Administratrix For The Estate Of Tan Ewe Kwang, Deceased) & Ors, there was no plain factual error regarding the High Court's factual finding of negligence against the 2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th appellants. (paras 24-26)

(3) The High Court had made a plain error of fact in not dismissing the suit against the 1st, 4th, 5th, 6th, and 13th to 16th appellants, given the absence of any evidence regarding the medical negligence allegedly committed by the said appellants and the factual finding of negligence of the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants, and no notice of cross-appeal was filed by the respondent to vary the finding against the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants so as to impose liability on the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th appellants. (paras 27-28)

(4) Based on expert evidence, the breach of duty of care by the 2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th appellants had materially contributed to the respondent's brain damage. Accordingly, as was decided in Wu Siew Ying v. Gunung Tunggal Quarry & Construction Sdn Bhd & Anor, the fact that the respondent's brain damage could have been caused by AFE, the respondent's pre-existing health problem, and/or DW5's negligence, was not relevant. (paras 28-30)

(5) The 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants could not rely on s 12(1) of the Civil Law Act 1956 ("CLA") to reduce their liability to the respondent, as the said provision provided a defence of contributory negligence only when a patient's death, injury, damage or loss was caused partly by the patient's 'fault' as defined in s 12(6) of the CLA to mean, a patient's 'negligence' (not the doctor's negligence). In this regard, the respondent's pre-existing health problem was not the respondent's negligence and could not therefore constitute a 'fault' within the meaning of s 12(1) read with 12(6) of the CLA. Additionally, the respondent was not guilty of any contributory negligence that had contributed to her brain damage. (para 32)

(6) Since the 2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th appellants were the 17th appellant's employees at the material time, it was, thus, vicariously liable for their breach of duty. Additionally, the 17th appellant was liable to the respondent for breach of contract by failing to have in place, or follow proper and effective systems in providing healthcare services to the respondent, and failing to engage competent healthcare practitioners. (paras 33-34)

(7) The 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th appellants could not rely on DW5's negligence to exclude or reduce their liability to the respondent, and should have instituted third party proceedings against DW5 for an indemnity or contribution from DW5 with regard to their liability. (paras 35-36)

(8) Although there was no rule of law for a trial court to give a discount on an award of damages when a claimant only adduced oral testimony in support of the award, in the interest of justice, the trial court had the discretion to give a fair and reasonable reduction or discount with regard to an award of damages. Where a discount was given, it would be incumbent on the court to give reasons for the same. (para 40)

(9) Premised on Inas Faiqah Mohd Helmi v. Kerajaan Malaysia & Ors, the respondent's future medical consultations, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, contracture release surgery and hospital admission for respiratory infection would be available free of charge in Government Hospitals/Clinics. Notwithstanding the fact that the said treatments and hospitalisation could be obtained for free, it was fair and reasonable in the circumstances to reduce the awards made by the High Court in respect of the same. The decision on quantum was varied accordingly. (paras 41, 44 & 45)

Case(s) referred to:

Azizi Amran v. Hizzam Che Hassan [2006] 1 MLRA 577 (refd)

Dr Chandran Gnanappah v. Gan See Joe & Anor And Another Appeal [2025] 5 MLRA 203 (refd)

Inas Faiqah Mohd Helmi v. Kerajaan Malaysia & Ors [2016] 1 MLRA 647 (folld)

Jag Singh v. Toong Fong Omnibus Co Ltd [1964] 1 MLRA 682 (refd)

Jamiah Holam v. Koon Yin [1982] 1 MLRH 775 (refd)

Jaswant Singh v. Central Electricity Board And Anor [1967] 1 MLRH 512 (refd)

Kuala Terengganu Specialist Hospital Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Ahmad Thaqif Amzar Ahmad Huzairi & Other Appeals [2023] 1 MLRA 601 (refd)

Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 (folld)

Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v. Morts Dock & Engineering Co Ltd (The Wagon Mound No 1) [1961] 1 All ER 404 (refd)

Qi Qiaoxian & Anor v. Sunway Putra Hotel Sdn Bhd [2024] 4 MLRA 49 (refd)

Tan Kuan Yau v. Suhindrimani Angasamy [1985] 1 MLRA 183 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Transformer Repairs & Services Sdn Bhd & Ors [2024] 1 MLRA 616 (refd)

Thirukumaran Shanmugam v. Nyana Prakash Sepiah [2023] MLRHU 710 (refd)

Topaiwah v. Salleh [1968] 1 MLRA 580 (refd)

Wah Shen Development Sdn Bhd v. Success Portfolio Sdn Bhd [2019] 2 MLRA 73 (refd)

Wu Siew Ying v. Gunung Tunggal Quarry & Construction Sdn Bhd & Anor [2010] 3 MLRA 78 (folld)

Legislation referred to:

Civil Law Act 1956, s 12(1), (6)

Rules of Court 2012, O 15 r 6(1), O 16 r 1(1)(a)

Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994, r 8(1)

Counsel:

For the appellants: Nik Mohd Noor Nik Kar (Adiba Iman Md Hassan & Arina Azmin Ahmad Marzuki with him); AG's Chambers

For the respondent: Manmohan Singh Dhillon (Karthi Kanthabalan & Pravin Kumar Gobinathan with him); M/s P S Ranjan & Co

[For the High Court judgment, please refer to Yusnita Johari v. Dr Jerilee Mariam Khong & Ors [2023] 4 MLRH 263]

JUDGMENT

Wong Kian Kheong JCA:

A. Introduction

[1] This judgment discusses, among others, the effect of the "Egg-Shell Skull" rule or "Thin Skull" rule (a tortfeasor takes the victim as the tortfeasor finds the victim) in medical negligence claims

B. Background

[2] I will refer to the parties as they were in the High Court.

[3] The plaintiff (Plaintiff) was pregnant with her second child in 2013. On 11 November 2013, the Plaintiff was referred to Hospital Sultanah Aminah, Johor Bahru (Hospital), from "Klinik Kesihatan". At that time-

(1) the foetus inside the Plaintiff's uterus was at about 33 weeks of gestation;

(2) the Plaintiff was diagnosed with "Placenta Praevia Type III Posterior" [PP Type 3 (Posterior)]; and

(3) the Plaintiff had no prior history of antepartum haemorrhage (bleeding from the genital tract prior to delivery of baby).

[4] The Plaintiff was scheduled for an elective Caesarean section (C-section) on 16 December 2013 [at 38 weeks' period of amenorrhoea (period of time without menstruation)]. While waiting for the elective C-section, the Plaintiff was warded in the Hospital for rest and monitoring.

[5] On 12 December 2013-

(1) the Plaintiff started to have contraction pain. Consequently, at 11.05am, she underwent an emergency C-section under general anaesthesia for the delivery of her second child;

(2) a baby boy was delivered at 11.17am weighing 3.1 kg;

(3) soon after delivery of the baby in the operating theatre (OT), the Plaintiff became bradycardic (slow heart rate) with a heart rate of 40 beats per minute (bpm). Oxygen saturation and capnograph (methods to record the Plaintiff's respiratory status) were not recordable;

(4) the Plaintiff subsequently developed Pulseless Electrical Activity, i.e., the Plaintiff's heart had stopped beating ( Plaintiff's Collapse). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was immediately administered on her. After five minutes of CPR, there was a return of spontaneous circulation with pulse rate of 145 bpm and blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg;

(5) the Plaintiff was diagnosed with Amniotic Fluid Embolism (AFE), namely, amniotic fluid (which surrounds the foetus in the uterus) had breached the placental barrier and entered the mother's bloodstream);

(6) the Plaintiff subsequently developed bleeding from vagina and puncture sites. She had Primary Postpartum haemorrhage (bleeding from the genital tract after delivery of baby) with Disseminated Intravascular Coagulopathy (formation of blood clots throughout the body's blood vessels). She suffered blood loss and was given, among others, a blood transfusion; and

(7) the emergency C-section lasted for about two hours. The care of the Plaintiff in the OT was provided by-

(a) a medical specialist and a medical officer (MO) from the Hospital's Obstetrics Department; and

(b) one specialist and one MO from the anaesthesia team in the Hospital.

[6] The Plaintiff was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit of the Hospital (ICU), where she was treated.

[7] The Plaintiff subsequently suffered severe and irreversible brain damage (Plaintiff's Brain Damage).

[8] The Plaintiff was discharged from ICU on 26 December 2013 but was warded in the Hospital for rehabilitation, including physiotherapy, occupational, and speech therapy.

[9] On 3 April 2014, the Plaintiff was discharged from the Hospital.

C. Proceedings In The High Court

[10] The Plaintiff filed this suit in the High Court (This Suit) through her husband and litigation representative, Encik Khairil Faiz bin Rahamat (PW5), against 17 defendants (Defendants), namely:

(1) 16 individual defendants ("1st Defendant" to "16th Defendant"). The 1st to 16th Defendants are-

(a) the doctors and nurses at the Hospital who were involved in the Plaintiff's C-section, treatment and management; and

(b) employed by the Government (17th Defendant); and

(2) the 17th Defendant owns and manages the Hospital.

[11] In This Suit-

(1) the Plaintiff claimed from the Defendants for, among others, general damages and special damages in respect of, among others, the Plaintiff's Brain Damage based on the following two causes of action:

(a) the tort of medical negligence; and

(b) breach of contract between the Plaintiff and 17th Defendant [Contract (Plaintiff-17th Defendant)];

(2) the Plaintiff alleged against the 1st to 16th Defendants as follows, among others-

(a) there was a failure to undertake close monitoring of the Plaintiff following the Plaintiff's Collapse in the OT;

(b) there was a failure to estimate properly the volume of blood loss suffered by the Plaintiff;

(c) there was a failure to undertake proper transfusion of blood and the proper blood volume replacement for the Plaintiff;

(d) there was a failure to properly treat the Plaintiff's metabolic abnormalities;

(e) there was a failure to undertake proper cooling therapy for the Plaintiff's cerebrum (brain); and

(f) there was a failure to have a proper and adequate system for multidisciplinary consultation, discussion, treatment and management of the Plaintiff's condition; and

(3) the Plaintiff's allegations against the 17th Defendant were as follows-

(a) the 17th Defendant failed to have in place or follow proper and effective systems in providing healthcare services to the Plaintiff;

(b) the 17th Defendant failed to engage healthcare practitioners with sufficient qualifications and experience;

(c) the 17th Defendant failed to provide sufficient facilities for the proper and effective management of patients such as the Plaintiff; and

(d) the 17th Defendant failed to inform the Plaintiff of treatment options elsewhere for better management of her condition.

[12] At the trial in the High Court (Trial)-

(1) the Plaintiff called eight witnesses as follows-

(a) the Plaintiff's sister-in-law, Puan Rashidah bt Rahamat (PW1);

(b) Puan Saleha bt Hamdan (PW2), the Plaintiff's mother-in-law;

(c) the Plaintiff's mother, Puan Maini bt Suliman (PW3);

(d) Puan Siti Robiah bt Johari (PW4), the Plaintiff's elder sister;

(e) PW5;

(f) Professor Dr Chan Yoo Kuen (PW6), a consultant anaesthesiologist in the University of Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), was the Plaintiff's expert witness regarding the question of whether the Defendants were liable for medical negligence to the Plaintiff (Liability Issue);

(g) Dr Milton Lum Siew Wah (PW7), a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist (O&G) in Alpha Specialist Centre, was the second expert witness for the Plaintiff in respect of the Liability Issue; and

(h) a consultant rehabilitation physician in UMMC, Professor Dr Lydia bt Abdul Latif (PW8), was the Plaintiff's expert witness for the question of how much the Defendants would be liable in damages to the Plaintiff (Quantum Issue) (on the assumption that the Defendants were liable to the Plaintiff); and

(2) the following six witnesses testified for the Defendants-

(a) with regard to the Quantum Issue, Dr Akmal Hafizah bt Zamli, a consultant rehabilitation physician from the Sungai Buloh Hospital (DW1);

(b) the 2nd Defendant (Dr Senthi s/o N Muthuraman);

(c) the 9th Defendant (Dr Shazlina Shirin bt Jamaludin);

(d) the 10th Defendant (Dr Adlina bt Hisyamuddin);

(e) Professor Dr Nor' Azim Mohd Yunos (DW5), a sessional intensivist (an expert doctor who specialises on care of critically ill patients, eg., patients in ICU), was involved in the treatment and management of the Plaintiff in this case. DW5 was not an employee of the 17th Defendant; and

(f) Dr Mohd Rohisham bin Zainal Abidin (DW6) of the Tengku Ampuan Rahimah Hospital, Klang, a consultant anaesthesiologist, was the sole expert for the Defendants in respect of the Liability Issue.

[13] After the Trial, on 15 April 2021, the following decision was delivered by the High Court (High Court's Decision)-

(1) with regard to the Liability Issue, the High Court gave judgment in favour of the Plaintiff against the Defendants [High Court's Decision (Liability)]; and

(2) the learned High Court Judge awarded damages to be paid by the Defendants to the Plaintiff in respect of the Quantum Issue [High Court's Decision (Quantum)].

[14] In the grounds of judgment of the High Court (GOJ), among others:-

(1) the learned High Court Judge made the following findings of fact-

(a) there was inadequate documentation of the Plaintiff's blood loss — paras 37 to 44, 99.6 and 99.7 GOJ;

(b) there was a failure to bring down the Plaintiff's temperature which was a material contribution to the Plaintiff's Brain Damage — paras 45 to 65 and 99.1 GOJ;

(c) there was a failure to bring down the Plaintiff's metabolic lactate acidosis level — paras 66 to 74 and 99.5 GOJ;

(d) the Plaintiff's sedation was prematurely withdrawn and this materially contributed to the Plaintiff's permanent brain damage — paras 75 to 77, 79 to 89 and 99.2 GOJ;

(e) Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) should not have been applied on the Plaintiff — paras 90 to 93 and 99.4 GOJ;

(f) excessive doses of adrenaline and noradrenaline had been administered to the Plaintiff — paras 94 to 96 and 99.9 GOJ; and

(g) the learned High Court Judge did not believe the 2nd Defendant — para 105 GOJ;

(2) the Defendants did not call an expert in O&G to rebut the expert opinion of PW7, an O&G expert — paras 118 to 120 and 122 GOJ;

(3) the High Court had found as a fact that-

(a) the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants were liable for the tort of medical negligence to the Plaintiff [Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants)] — paras 131 to 145 GOJ; and

(b) even though DW5 was not an employee of the 17th Defendant, DW5 was liable for medical negligence to the Plaintiff (DW5's Negligence) — para 130 GOJ; and

(4) the 17th Defendant was liable to the Plaintiff as follows-

(a) the 17th Defendant was vicariously liable to the Plaintiff because the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants were the 17th Defendant's employees at the material time; and

(b) the breach of the Contract (Plaintiff-17th Defendant) with regard to the 17th Defendant's "organizational and system failures" — para 147 GOJ.

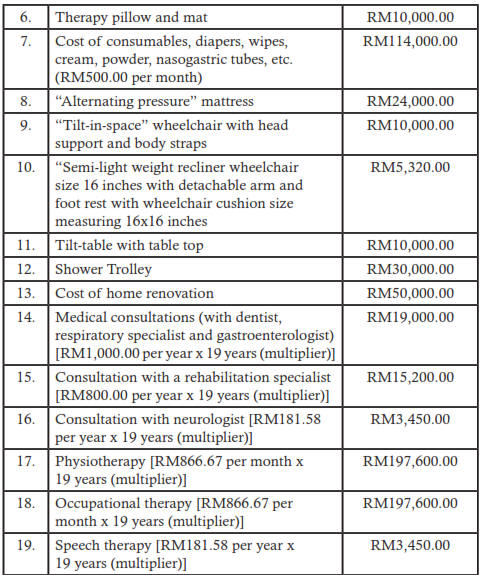

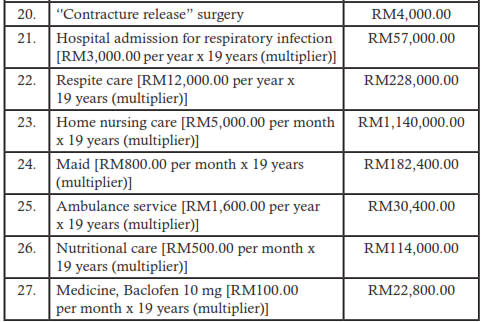

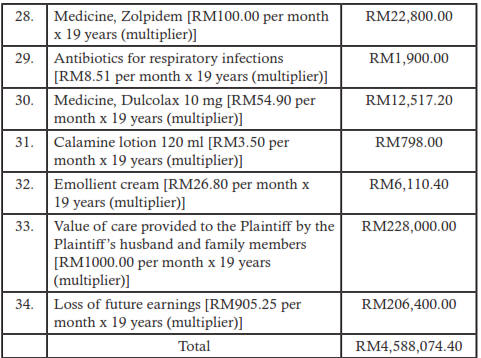

[15] According to the High Court's Decision (Quantum), the Defendants were liable to the Plaintiff as follows:

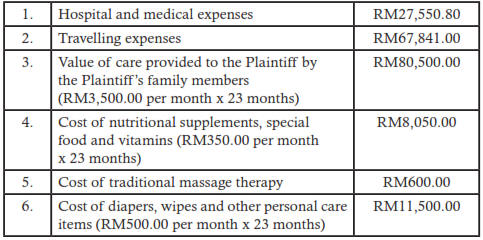

(1) special damages for the period of 23 months (from 12 December 2013 to 7 December 2015)-

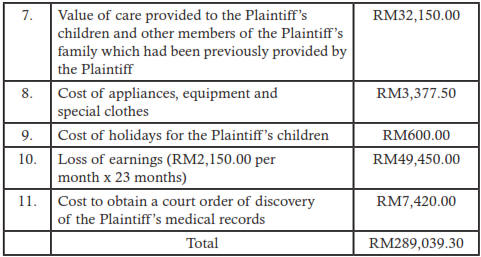

(2) damages for the period of 63 months, from 7 December 2015 to 30 April 2021 (Pre-Trial Damages)-

(3) a sum of RM400,000.00 was awarded as general damages for pain, suffering and loss of amenities [General Damages (Pain/ Suffering/Loss of Amenities)]; and

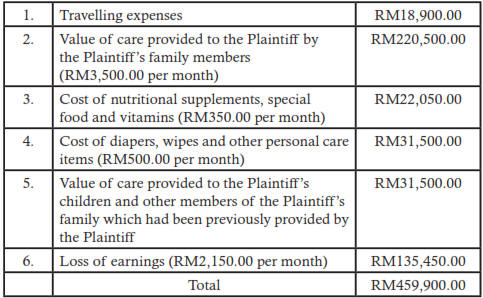

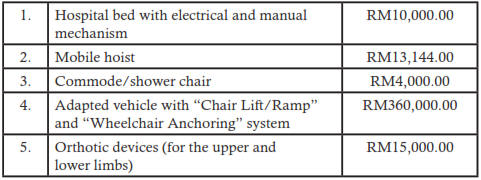

(4) general damages for the future [General Damages (Future)]-

[16] The learned High Court Judge determined the costs of This Suit [Costs (High Court)] as follows:

(1) the Defendants shall pay to the Plaintiff a sum of RM250,000.00 for getting-up (GU); and

(2) an amount of RM104,682.47 was awarded in favour of the Plaintiff as "out-of-pocket expenses" (OPE).

[17] With regard to interest-

(1) the Defendants shall pay to the Plaintiff interest on special damages at the rate of 4% per annum (pa) from 12 December 2013 (date of the Plaintiff's C-section) until 15 April 2021, the date of the High Court's Decision [Date (High Court's Judgment)];

(2) interest at the rate of 8% pa on the Pre-Trial Damages and General Damages (Pain/Suffering/Loss of Amenities) shall be paid by the Defendants to the Plaintiff from 9 December 2016 (date of the service of the writ on the Defendants) until the Date (High Court's Judgment);

(3) interest at the rate of 5% pa on the General Damages (Future) from the Date (High Court's Judgment) until full payment of the same; and

(4) no interest was awarded for the Costs (High Court).

D. Proceedings In The Court of Appeal

[18] The Defendants filed an appeal to the Court of Appeal (This Appeal) against both the High Court's Decision (Liability) and the High Court's Decision (Quantum).

E. Contentions Of The Parties

[19] In support of This Appeal, Encik Nik Mohd Noor bin Haji Nik Kar, the learned Senior Federal Counsel (SFC), advanced the following submission, among others, on behalf of the Defendants:

(1) with regard to the Liability Issue-

(a) when the Plaintiff was admitted to the Hospital, she was already a "high r/s/c" patient with a pre-existing medical problem, namely, PP Type 3 (Posterior) (Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem). The Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem had contributed to and/or worsened the Plaintiff's Brain Damage. Hence, the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem should exclude, either totally or partially, the liability of the Defendants in this case;

(b) based on-

(i) the testimonies of the 2nd, 9th and 10th Defendants; and

(ii) the expert opinion of DW6

— the Plaintiff had failed to discharge the legal and evidential burden to prove on a balance of probabilities that the Defendants were liable to her for medical negligence with regard to the Plaintiff's Brain Damage [Legal/Evidential Burden];

(c) in view of the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants), This Appeal by the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th Defendants should be allowed on this ground alone;

(d) despite DW5's Negligence, the Plaintiff did not sue DW5 in This Suit;

(e) the learned High Court Judge had erred in fact by rejecting the expert view of DW6 on the ground that DW6 is employed by the 17th Defendant;

(f) the High Court Judge should have recognised that AFE is a rare occurrence wherein there is no "universally accepted diagnostic criteria" and "standard treatment protocol'. Hence, the Defendants should not be liable for medical negligence in this case because the Plaintiff's Brain Damage was due to AFE; and

(g) the High Court should have decided that the Plaintiff was 75% liable for the Plaintiff's Brain Damage while the Defendants should only be 25% liable due to the following two reasons-

(i) the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem; and

(ii) the fact that AFE is a rare occurrence; and

(2) in respect of the Quantum Issue-

(a) the High Court should have applied an "Evidence-based Medicine" (EBM) approach to decide the Quantum Issue. In other words, the learned High Court Judge should only award damages, both special and general, for the treatment of the Plaintiff if such treatment was necessary for her;

(b) the High Court should only award a reasonable amount of damages to the Plaintiff. The learned SFC relied on the following cases-

(i) the judgment of the Federal Court delivered by Abdull Hamid Embong FCJ in Inas Faiqah Mohd Helmi v. Kerajaan Malaysia & Ors [2016] 1 MLRA 647 and

(ii) the decision of Gunalan Muniandy JCA in the Court of Appeal in Kuala Terengganu Specialist Hospital Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Ahmad Thaqif Amzar Ahmad Huzairi & Other Appeals [2023] 1 MLRA 601; [Court of Appeal's Judgment (Ahmad Thafiq Amzar)]. The Court of Appeal's Judgment (Ahmad Thafiq Amzar) had been varied on appeal to the Federal Court [Federal Court's Order (Ahmad Thafiq Amzar)]. However, there is no written judgment by the Federal Court in Ahmad Thafiq Amzar; and

(c) the learned SFC had submitted at length on various items of special and general damages awarded by the High Court (which would be addressed below).

[20] Mr Manmohan Singh Dhillon, the Plaintiff's learned counsel, had urged this court to dismiss This Appeal with costs on the following grounds, among others:

(1) the High Court's Decision (Liability) should be upheld because-

(a) the learned High Court Judge did not make any plain error of fact in deciding the Liability Issue in favour of the Plaintiff against the Defendants; and

(b) with regard to the Plaintiff's Prior Health Problem, in accordance with the Egg-Shell Skull rule, the Defendants should accept the Plaintiff as she was at the time of her admission to the Hospital on 11 November 2013; and

(2) there should not be any appellate intervention with regard to the High Court's Decision (Quantum) as-

(a) the learned High Court Judge did not act on a wrong principle of law in respect of the High Court's Decision (Quantum); and

(b) the learned High Court Judge's award of damages was not manifestly excessive.

F. Issues

[21] The following questions will be determined in This Appeal:

(1) should the High Court consider the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem with regard to the Liability Issue and Quantum Issue? In this regard, whether the Egg-Shell Skull rule applies in medical negligence cases and if so, to what extent?;

(2) in respect of the Liability Issue-

(a) was there a plain factual error regarding the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants)?;

(b) did the learned High Court Judge make a plain error of fact in not dismissing This Suit against the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th Defendants?;

(c) whether the medical negligence of the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants had materially contributed to the Plaintiff's Brain Damage;

(d) could the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem exclude or reduce the liability of the Defendants in this case? This question also discusses whether the Defendants could rely on s 12(1) of the Civil Law Act 1956 (CLA) to support This Appeal;

(e) was the 17th Defendant liable to the Plaintiff for a breach of the Contract (Plaintiff-17th Defendant)?; and

(f) can the Defendants rely on DW5's Negligence to exclude or reduce their liability to the Plaintiff in this case?;

(3) regarding the Quantum Issue-

(a) whether there is a rule of law that the court should give a discount on an award of damages when the claimant only adduces oral evidence in support of the award;

(b) can the court refuse to grant damages for cost of future medical treatment [Damages (Cost of Future Medical Treatment)] on the ground that such medical treatment is available for free in Government hospitals and clinics (Government Hospitals/ Clinics)? In this regard, should the court apply the "fair and reasonable" test as laid down by the Federal Court in Inas Faiqah?; and

(c) whether the High Court's award of any item of damages was "so extremely high" which warrants appellate intervention;

(4) can the learned High Court Judge order interest at the rate of 8% pa on the Pre-Trial Damages and General Damages (Pain/ Suffering/Loss of Amenities)?; and

(5) if the Defendants were partially successful in This Appeal, should the Costs (High Court) be reduced accordingly?

G. Application Of The Egg-Shell Skull Rule In Medical Negligence Cases

[22] I wish to highlight the following Malaysian cases which had applied the Egg-Shell Skull rule:

(1) in the Court of Appeal case of Azizi Amran v. Hizzam Che Hassan [2006] 1 MLRA 577, at [8] to [10], Zulkefli Ahmad Makinuddin JCA (as he then was) decided as follows-

"[8] Before the learned judge of the High Court and before us in this appeal, Mr Brijnandan submitted that the court must accept the man as he is, that is, that he is suffering from 4cm shortening of the left leg and that the court ought to make an award on that basis. However, the learned judge found that it was not a fair submission to make and went on to state that a tort-feasor is only liable for the actual and related consequential suffering occasion to the plaintiff as a direct result of the tortfeasor's negligence. The actual shortening attributed to the subsequent accident is 2 to 2.5cm shortening and the learned judge was of the view that this is the damage that the present defendant is liable for. In this case there was evidence led that the plaintiff had already made a claim for the previous 2cm shortening through another counsel in an earlier civil suit filed. For this reason the learned judge of the High Court found that the plaintiff's request to treat this case like the egg-shell cases is totally out of line as the plaintiff cannot be allowed to enrich himself twice over the same injury.

[9] The issue that arises in this appeal, is whether the court should have considered an award based on 2.5cm or on 4.0cm shortening of the left leg. It is not disputed in this case that the plaintiff has been compensated for the first accident. It is our considered view that the award should be on the basis of 4.0cm shortening with a slight scaling down for compensation the plaintiff received in the first accident. In this regard, we would agree with the submission of learned counsel for the plaintiff that the defendant must take his victim as he finds him. This is the egg-shell skull rule. On this point, in the case of Watts v. Rake [1960] 18 CLR 158, Dixon CJ at p 160 had this to say:

If the injury proves more serious in its incidents and its consequences because of the injured man's condition, that does nothing but increase the damages the defendant must pay. To sever the remaining leg of a one-legged man or put out the eye of a one-eyed man is to do a far more serious injury than it would have been had the injured man possessed two legs or two eyes. But for the seriousness of the injury the defendant must pay. In the same case Menzies J at p 164 stated as follows: 'A negligent defendant must take his victim as he finds him and pay damages accordingly. The fact that the person injured was peculiarly susceptible to ensuing complications that would not in a normal person have followed from the injuries received, or that the person injured already had a disability which made the injury the more disabling — eg the loss of an only eye — does not mean that damages are not to be assessed according to the circumstances of the particular case. Still, on the same point in the case of Hughes v. Lord Advocate [1963] AC 837 (HL) at p 845 Lord Reid in his speech inter alia said: "A defendant is liable, although the damage may be a good deal greater in extent than was foreseeable. He can only escape liability if the damage can be regarded as differing in kind from what was foreseeable."

[10] With respect to the findings of the learned judge, it would appear that his findings are clearly against the principle as set out in the above cited case authorities. His Lordship erred in not taking into consideration the effect of the present overall disability of 4 cm suffered by the plaintiff. Prior to this accident, the plaintiff had a shortening of 1.5 to 2.0 cm. However, this did not disable him for he kept working. The plaintiff only received crippling disabilities in the present accident We are of the view that the learned judge of the High Court was therefore wrong when he refused to take the present disabilities including the previous injuries into consideration in deciding whether to enhance the award made by the learned trial Sessions Court Judge."

[Emphasis Added];

(2) according to Badariah Sahamid JCA in the Court of Appeal in Wah Shen Development Sdn Bhd v. Success Portfolio Sdn Bhd [2019] 2 MLRA 73 at [24]-

"[24] The authorities refer to the 'egg shell skull principle' as vulnerabilities or weaknesses of specific plaintiffs in negligence cases. According to this principle, a defendant cannot plead the peculiar vulnerabilities or sensitivities of a plaintiff to avoid liability to a plaintiff."

[Emphasis Added]; and

(3) in the High Court case of Thirukumaran Shanmugam v. Nyana Prakash Sepiah [2023] MLRHU 710, at [12] to [16] and [21], Tee Geok Hock J delivered the following judgment-

"Thin skull rule

[12] It is a common law rule that a tortfeasor cannot complain if the injuries he has caused turn out to be more serious than expected because his victim suffered from a pre-existing weakness or other vulnerability, such as an unusually thin skull or unusually weak medical condition which pre-existed before the commission of the tort. A tortfeasor must take his victim as he finds him: see Smith v. Leech Brain & Co Ltd [1962] 2 QB 405. This rule is also known as the eggshell skull rule.

[13] As the tortfeasor's liability is only to the extent of compensating for the injuries caused by his tortious wrong, the compensation the tortfeasor has to pay to the plaintiff should not be to the extent of making any improvement to the plaintiff's pre-existing condition or weakness. Thus, many legal practitioners take the position that the thin skulled rule is counter-balanced by another legal principle which provides that a tortfeasor does not have to put the plaintiff in a better position than he would have been in if he was never injured. To them, the "crumbling skull" plaintiff is a relative of the thin skulled plaintiff and can also be considered as a rule of law.

[14] The "crumbling skull" rule simply recognizes that a person's preexisting condition was inherent in the person's "original position" and the tortfeasor need not put the plaintiff in a position better than before the injury occurred. The defendant is liable for the injuries and impairments caused, even if they are extreme, but need not compensate the plaintiff for any debilitating effects of the pre-existing condition which the plaintiff would have experienced anyway. Many defendants will try to argue that the plaintiff had a "crumbling skull" in cases where the plaintiff is alleging a "thin skull" in order to reduce the damages ultimately payable.

[15] Analysed in another perspective, both the "thin skull" rule and the "crumbling skull" rule are logical and practical applications of the law of causation and effect and the scope of the tortfeasor's liability for damages.

[16] In Malaysia, the thin skull rule has been recognised in a number of decided authorities.

[21] In light of the above decided authorities, this Court holds that it is well-settled in Malaysia that the thin skill rule, also known as the eggshell skull rule, is an accepted principle of law in Malaysia."

[Emphasis Added]

[23] I am of the following view regarding the application of the Egg-Shell Skull rule in medical negligence cases:

(1) in Dr Chandran Gnanappah v. Gan See Joe & Anor And Another Appeal [2025] 5 MLRA 203, at [25], [29] and [30], the Court of Appeal has explained that a doctor owes the following duty of care to a patient (Doctor's Duty of Care)-

"[25] With regard to the tort of professional medical negligence, a doctor owes a duty of care to a patient in respect of the following three matters:

(1) the doctor's diagnosis of the patient's medical problem (Diagnosis);

(2) the doctor's advice to the patient [Advice (Proposed Treatment/ Surgery)] regarding the proposed treatment and/or surgery for the patient (Proposed Treatment/Surgery); and

(3) the Treatment/Surgery which had been carried out in relation to the patient.

[29] Premised on Foo Fio Na and Montgomery, the Duty of Care [Advice (Proposed Treatment/Surgery)] is as follows:

(1) a doctor has a duty to take reasonable care to ensure that the patient is informed of two matters-

(a) any inherent or material risk involved in the Proposed Treatment/Surgery; and

(b) any reasonable alternative to the Proposed Treatment/ Surgery or variant of the Proposed Treatment/Surgery

— so as to enable the patient to make an informed decision and elect on whether to proceed or not with the Proposed Treatment/ Surgery; and

(2) a risk is material if —

(a) a reasonable person in the patient's position would be likely to attach significance to the risk; and/or

(b) the doctor is or should reasonably be aware that the particular patient would be likely to attach significance to the risk.

[30] With regard to the standard of the duty of care for a doctor's diagnosis, treatment and/or surgery [Duty of Care (Diagnosis/ Treatment/Surgery)] -

(1) what was the view of the general body of doctors regarding the Diagnosis/Treatment/Surgery for the patient at the material time [View of General Body of Doctors (Patient's Diagnosis/Treatment/Surgery)] — please refer to the judgment of McNair J in UK's High Court case of Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 582, at 586 to 588. Bolam had been affirmed by our Federal Court in Zulhasnimar, at [97];

(2) can the View of General Body of Doctors (Patient's Diagnosis/Treatment/Surgery) withstand logical analysis? — please refer to the decision of Lord Browne-Wilkinson in the House of Lords in Bolitho v. City & Hackney Health Authority [1997] 3 WLR 1151, at 1160. Bolitho had been approved in Zulhasnimar, at [97]; and

(3) if the View of General Body of Doctors (Patient's Diagnosis/Treatment/Surgery) could withstand logical analysis, whether the doctor's Diagnosis/Treatment/ Surgery was done in accordance with the View of General Body of Doctors (Deceased's Diagnosis/Treatment/ Surgery).

If the answer to the above question is -

(a) in the affirmative, the doctor cannot be liable for professional medical negligence; and

(b) negative, the doctor has committed professional medical negligence."

[Emphasis Added];

The nature and extent of a Doctor's Duty of Care (1st Question) may depend on, among others, the patient's pre-existing medical problem and/or vulnerability (Patient's Pre-Existing Medical Problem/ Vulnerability).

When the court decides the question of whether the Doctor's Duty of Care has been breached [Breach (Doctor's Duty of Care)] (2nd Question), the Patient's Pre-Existing Medical Problem/Vulnerability may be taken into account by the court (2nd Question).

Understandably, the 1st and 2nd Questions (collectively referred to in this judgment as the "2 Questions") are factual. Needless to say, a patient has the Legal/Evidential Burden to satisfy the court on a balance of probabilities regarding the occurrence of the Breach (Doctor's Duty of Care);

(2) if the court decides that there is a Breach (Doctor's Duty of Care), the patient must prove on a balance of probabilities that the Breach (Doctor's Duty of Care) had materially contributed to the patient's death, injury, damage and/or loss (Patient's Death/ Injury/Damage/Loss) (3rd Question) — please refer to the judgment of the Federal Court delivered by Richard Malanjum CJ (Sabah & Sarawak) (as he then was) in Wu Siew Ying v. Gunung Tunggal Quarry & Construction Sdn Bhd & Anor [2010] 3 MLRA 78, at [36]. The 3rd Question is factual and the court may consider the Patient's Pre-Existing Medical Problem in deciding the 3rd Question; and

(3) if the Breach (Doctor's Duty of Care) had materially contributed to the Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss-

(a) the court should consider whether the Pre-Existing Patient's Medical Problem has become worse due to the Breach (Doctor's Duty of Care) [Exacerbation (Pre-Existing Patient's Medical Problem)];

(b) if there is an Exacerbation (Pre-Existing Patient's Medical Problem), the Egg-Shell Skull rule can apply and the doctor shall therefore be liable for the Exacerbation (Pre-Existing Patient's Medical Problem) — please refer to Azizi Amran and Thirukumaran. However, if the Exacerbation (Pre-Existing Patient's Medical Problem) is part of the Patient's Death/ Injury/Damage/Loss, the patient is already entitled to claim for the Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss. Hence, there cannot be a double recovery by the patient for Exacerbation (Pre-Existing Patient's Medical Problem) and the Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss; and

(c) if the Pre-Existing Patient's Medical Problem is not worsened by the Breach (Doctor's Duty of Care), there is no room to invoke the Egg-Shell Skull rule.

H. Was The Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence Of The 2nd, 3rd, And 7th To 12th Defendants) Plainly Erroneous?

[24] This case concerned whether the Defendants had breached their duty of care to the Plaintiff in respect of-

(1) the C-section performed on the Plaintiff; and

(2) the subsequent treatment of the Plaintiff in the ICU [Duty of Care (Surgery/Treatment)].

With regard to the nature and extent of the Duty of Care (Surgery/ Treatment)-

(a) the "view of the general body of doctors" had been given in the expert opinions of PW6 and PW7 [Expert Evidence (PW6 and PW7)]. The Expert Evidence (PW6 and PW7) could withstand logical scrutiny; and

(b) the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem was a relevant consideration but could not, in itself, exclude the Duty of Care (Surgery/Treatment).

[25] As decided by the Federal Court's judgment delivered by Zabariah Yusof FCJ in Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193, at [33] and [34], as a trial court has the audio-visual advantages (vis-à-vis an appellate court) of listening to the oral testimonies of witnesses and assessing their demeanour, an appellate court can only set aside a trial court's finding of fact if the factual finding is "plainly wrong" in the sense that-

(1) the trial court's finding of fact could not be reasonably explained or justified; and

(2) no reasonable trial judge could have arrived at the trial court's finding of fact.

[26] Premised on Ng Hoo Kui, I am satisfied that there was no plain factual error regarding the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of 2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th Defendants). The following evidence and reasons support the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of 2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th Defendants):

(1) according to the Expert Evidence (PW6 and PW7), the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants breached their Duty of Care (Surgery/ Treatment) [Breach (2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants)] in respect of the following matters:

(a) there was a failure to estimate properly the volume of blood loss suffered by the Plaintiff. In fact, according to PW7, there were discrepancies in the amount of blood loss of the Plaintiff which had been recorded in the records of the 17th Defendant;

(b) when there was no proper documentation of the Plaintiff's blood loss, consequently, there would not be a proper blood volume replacement for the Plaintiff;

(c) there was a delay in undertaking a proper transfusion of blood to the Plaintiff;

(d) there was a failure to undertake cooling therapy to protect the Plaintiff's cerebrum;

(e) there was a failure to bring down the Plaintiff's metabolic lactate acidosis level;

(f) there was a premature withdrawal of the Plaintiff's sedation;

(g) PEEP should not have been applied on the Plaintiff; and

(h) excessive doses of adrenaline and noradrenaline had been administered to the Plaintiff.

It is clear from the Expert Evidence (PW6 and PW7) that the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem did not cause or contribute to the Breach (2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants);

(2) the 2nd Defendant was the O&G who performed the C-section on the Plaintiff in the OT. Consequently, the 2nd Defendant had actual knowledge-

(a) of the Plaintiff's Collapse in the OT and the fact that CPR was immediately administered to resuscitate her; and

(b) the Plaintiff bled heavily in the OT and was given a blood transfusion;

(3) the Defendants did not call an O&G to give an expert testimony which could rebut the expert view of PW7 (an O&G); and

(4) the learned High Court Judge had made a finding of fact that the 2nd Defendant was not a credible witness. Such a factual finding was not plainly erroneous.

I. Should There Be Appellate Intervention Regarding The Liability Of The 1st, 4th To 6th And 13th To 16th Defendants?

[27] I am of the view that the learned High Court Judge had made a plain error of fact in not dismissing This Suit against the 1st, 4th to 6th, and 13th to 16th Defendants (High Court's Plain Factual Error). The following evidence and reasons support the High Court's Plain Factual Error:

(1) the Plaintiff had not adduced any evidence regarding the medical negligence committed by the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th Defendants in this case;

(2) the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants) had been made and yet, the learned High Court Judge did not dismiss This Suit against the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th Defendants. Furthermore, as explained in the above para 26, the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants) was not plainly wrong;

(3) the Plaintiff did not file a notice of cross-appeal pursuant to r 8(1) of the Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 (RCA) for the Court of Appeal to vary the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants) so as to impose liability for medical negligence in this case on the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th Defendants. Reproduced below is r 8(1) RCA-

"Rule 8. Notice of cross-appeal.

(1) It shall not be necessary for a respondent to give notice of appeal, but if a respondent intends, upon the hearing of the appeal, to contend that the decision of the High Court should be varied, he may, at any time after entry of the appeal and not more than ten days after the service on him of the record of appeal, give notice of cross-appeal specifying the grounds thereof, to the appellant and any other party who may be affected by such notice, and shall file within the like period a copy of such notice, accompanied by copies thereof for the use of each of the Judges of the Court."

[Emphasis Added]; and

(4) during the oral hearing of This Appeal, the Court of Appeal questioned Mr Manmohan Singh Dhillon on whether the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th Defendants were liable for medical negligence to the Plaintiff in this case. In the finest traditions of the Bar, Mr Manmohan Singh Dhillon rightly conceded that the 1st, 4th to 6th and 13th to 16th Defendants were not liable for medical negligence to the Plaintiff in this case.

[28] In view of the High Court's Plain Factual Error (as explained in the above para 27), This Appeal by the 1st, 4th to 6th, and 13th to 16th Defendants is allowed.

J. Had The Breach (2nd, 3rd And 7th To 12th Defendants) Materially Contributed To The Plaintiff's Brain Damage?

[29] With regard to the issue of causation, our Federal Court had decided in Wu Siew Ying, at [36], as follows:

"[36] In the light of these authorities, we are of the view that the 'but for' test is not the exclusive test to be applied to determine causation of the injury. It can still be applied but not in circumstance when there are two or more acts or events or factors that could or contribute to the injury of the plaintiff. This instant case is a case in point where evidence is established that there are a multiple of factors that could bring about the injury to the plaintiff. And to decide whether there is causation in these circumstances the approach of Lord Reid in Bonnington Casting Ltd v. Wardlaw: whether any of these acts or events or factors has materially contributed to the plaintiff's injury should be adopted. What is a material contribution must be a question of degree. This is for the court to decide but certainly anything that is trifle is not material. As Lord Reid in the same case expounded: 'contribution which comes within the exception of de minimis non curat lex (the law does not concerns itself with trifles) is not material."

[Emphasis Added]

Premised on Wu Siew Ying-

(1) where there are two or more causes of a Patient's Death/Injury/ Damage/Loss and one of these causes is the Breach (Duty of Care), the patient is only required to prove on a balance of probabilities that the Breach (Duty of Care) has materially contributed to the Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss; and

(2) upon proof that the Breach (Duty of Care) has materially contributed to the Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss, the fact that there may be other cause(s) for the Patient's Death/Injury/ Damage/Loss, is/are of no consequence.

[30] I am not able to accept the contention by the learned SFC that the Plaintiff's Brain Damage was caused by AFE, the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem, and/or DW5's Negligence. This is because, according to Expert Evidence (PW6 and PW7), the Breach (2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th Defendants) [please refer to the above sub-paragraph 26(1)] had materially contributed to the Plaintiff's Brain Damage [Material Contribution ( Plaintiff's Brain Damage)]. Accordingly, as decided in Wu Siew Ying, once there was proof that the Breach (2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants) was a Material Contribution (Plaintiff's Brain Damage), the fact that the Plaintiff's Brain Damage could have been caused by AFE, the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem and/or DW5's Negligence, was not relevant.

K. What Is The Effect Of The Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem?

[31] I reproduce below s 12(1) and (6) CLA:

"Apportionment of liability in case of contributory negligence

Section 12(1) Where any person suffers damage as the result partly of his own fault and partly of the fault of any other person, a claim in respect of that damage shall not be defeated by reason of the fault of the person suffering the damage, but the damages recoverable in respect thereof shall be reduced to such extent as the Court thinks just and equitable having regard to the claimant's share in the responsibility for the damage:

Provided that-

(a) this subsection shall not operate to defeat any defence arising under a contract; and

(b) where any contract or written law providing for the limitation of liability is applicable to the claim the amount of damages recoverable by the claimant by virtue of this subsection shall not exceed the maximum limit so applicable.

(6) In this section "fault" means negligence, breach of statutory duty or other act or omission which gives rise to a liability in tort or would, apart from this Act, give rise to the defence of contributory negligence."

[Emphasis Added]

[32] Contrary to the submission by the learned SFC, I am of the view that the 2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th Defendants cannot rely on s 12(1) CLA to reduce their liability to the Plaintiff in this case. This is because s 12(1) CLA provides a defence of contributory negligence only when a Patient's Death/ Injury/Damage/Loss is caused partly by the patient's "fault". Section 12(6) CLA has defined "fault" to mean, among others, a patient's "negligence" (not the doctor's medical negligence). The Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem was not the Plaintiff's negligence and could not therefore constitute a "fault" within the meaning of s 12(1) read with (6) CLA. Furthermore, in this case, the Plaintiff was not guilty of any contributory negligence which had contributed to the Plaintiff's Brain Damage. It is therefore clear that the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants cannot avail themselves of the Plaintiff's Pre-Existing Health Problem so as to exclude their liability to the Plaintiff, either wholly or partly.

L. Was The 17th Defendant Liable To The Plaintiff?

[33] Firstly, the 17th Defendant was vicariously liable to the Plaintiff in respect of the Breach (2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants). This was because the 2nd, 3rd and 7th to 12th Defendants were the employees of the 17th Defendant at the material time.

[34] Additionally, the 17th Defendant was liable to the Plaintiff for a breach of the Contract (Plaintiff-17th Defendant) because-

(1) the 17th Defendant had failed to have in place or follow proper and effective systems in providing healthcare services to the Plaintiff; and

(2) the 17th Defendant had failed to engage competent healthcare practitioners to treat and manage the Plaintiff properly.

M. Can The 2nd, 3rd, 7th to 12th And 17th Defendants Rely On DW5's Negligence To Exclude Or Reduce Their Liability To The Plaintiff?

[35] I have no hesitation in deciding that the 2nd, 3rd, 7th to 12th and 17th Defendants cannot rely on DW5's Negligence to exclude or reduce their liability to the Plaintiff [Liability (2nd, 3rd, 7th to 12th and 17th Defendants)] in this case. In this regard, I rely on O 15 r 6(1) of the Rules of Court 2012, which provides as follows:

"A cause or matter shall not be defeated by reason of the misjoinder or nonjoinder of any party, and the Court may in any cause or matter determine the issues or questions in dispute so far as they affect the rights and interests of the persons who are parties to the cause or matter."

[Emphasis Added]

By virtue of O 15 r 6(1) RC, This Suit "shall not be defeated by reason of the... non-joinder" of DW5 and the court may determine the issues in this case so far as they affect the rights and interests of all the parties — please refer to the Court of Appeal's judgment in Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Transformer Repairs & Services Sdn Bhd & Ors [2024] 1 MLRA 616, at [76(3)]. If the High Court's Decision is not affected by the non-joinder of DW5, DW5's Negligence cannot exclude or reduce the Liability (2nd, 3rd, 7th to 12th and 17th Defendants) in this case.

[36] The 2nd, 3rd, 7th to 12th and 17th Defendants should have instituted third-party proceedings under O 16 r 1(1)(a) RC against DW5 for an indemnity or contribution from DW5 with regard to the Liability (2nd, 3rd, 7th to 12th and 17th Defendants).

N. Quantum Issue

N(1). Whether A Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss Is Too Remote To Be Recoverable In Law

[37] The court can only award damages for a Patient's Death/Injury/ Damage/Loss if the patient can prove on a balance of probabilities that the Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss is not too remote in law and can be recovered as damages (Remoteness of Damage Issue). The Remoteness of Damage Issue is decided based on the "reasonable foreseeability' test as laid down by Viscount Simonds in the Privy Council in an appeal from Australia, Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v. Morts Dock & Engineering Co Ltd (The Wagon Mound No 1) [1961] 1 All ER 404, at p 413. The reasonable foreseeability test in The Wagon Mound No 1 has been adopted by Gill J (as he then was) in the High Court case of Jaswant Singh v. Central Electricity Board And Anor [1967] 1 MLRH 512 at pp 515-516.

N(2). When Can There Be Appellate Intervention Regarding a Trial Court's Award of Damages?

[38] If a Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss is reasonably foreseeable and is not too remote in law to be recovered by the patient, a trial court's assessment of damages for the Patient's Death/Injury/Damage/Loss can only be set aside or varied by an appellate court in the following limited circumstances:

(1) when the trial judge has applied the wrong principle — please refer to the judgment of the Supreme Court delivered by Abdul Hamid CJ (Malaya) (as he then was) in Tan Kuan Yau v. Suhindrimani Angasamy [1985] 1 MLRA 183, at pp 184-185;

(2) when the trial court's award of damages is "so very small' — please see the judgment of Azmi CJ (Malaya) (as he then was) in the Federal Court case of Topaiwah v. Salleh [1968] 1 MLRA 580, at p 582;

(3) when an award of damages by the trial judge is "so extremely high" — Topaiwah, at p 582;

(4) when the trial court had erroneously estimated the amount of damages by omitting to consider a relevant fact or had taken into account an irrelevant consideration — Tan Kuan Yau, at pp 184-185;

(5) when the trial judge's award of damages is "so much out of line with a discernable trend or pattern of awards in reasonably comparable cases that it must be regarded as having been a wholly erroneous estimate" — please refer to the judgment of the Privy Council (our highest court then) in Jag Singh v. Toong Fong Omnibus Co Ltd [1964] 1 MLRA 682, at p 685; and/or

(6) when the trial court has awarded damages based on "some misapprehension of facts" — please see Hashim Yeop Sani's (as he then was) judgment in the High Court case of Jamiah Holam v. Koon Yin [1982] 1 MLRH 775, at p 776.

N(3). Is There A Rule Of Law That The Court Should Give A Discount On An Award Of Damages When A Claimant Only Adduces Oral Evidence In Support Of The Award?

[39] I am not aware of any rule of law that the court is obliged to give a discount on an award of damages when a claimant only adduces oral testimony in support of the award. On the contrary, the following two judgments of the Court of Appeal have awarded damages based solely on oral evidence:

(1) Dr Chandran, at [61]; and

(2) it was decided in Qi Qiaoxian & Anor v. Sunway Putra Hotel Sdn Bhd [2024] 4 MLRA 49 at [60], as follows-

"[60] With respect to the Sessions Court and the High Court, we are of the view that a claimant can claim for special damages based solely on the credible testimony of a witness. This decision is premised on the following reasons:

(1) there is nothing in the [Evidence Act 1950] which has provided, either expressly or by necessary implication, that special damages can only be proven by way of documentary evidence. In fact, s 134 EA has stated that no particular number of witness shall in any case be required for the proof of any fact;

(2) in the High Court case of Nurul Husna Muhammad Hafiz & Anor v. Kerajaan Malaysia & Ors [2015] 1 MLRH 234, at [39] and [40], Vazeer Alam My din Meera JC (as he then was) has decided as follows -

"[39] Counsel for the defendants whilst agreeing that Nurul Husna may need to be fed special food, vitamins and nutritional supplements, argues that without proper documentary evidence of payment receipts for such purchases, a sum of RM200.00 per month would be more appropriate.

[40] I allowed the sum of RM44,500.00 as claimed by the plaintiffs as the amount claimed is not farfetched in today's prices and it would be too much to expect Nurul Husna's parents to keep documentary proof of expenses incurred for these expenses since her birth. In this regard, I accept the submissions of counsel for the plaintiffs that the evidence was clear that the irreversible injuries and disabilities suffered by Nurul Husna had and continue to have an overwhelming and debilitating effect on her parents and carers. Their resources were centred on first saving her life and next caring for her. In such circumstances it is unreasonable to expect Nurul Husna's parents to collect bills and receipts and filing them away with a view to bringing a claim especially when the defendants had hidden their culpability in the treatment and management provided to Nurul Husna. (See Overseas Investment Pte Ltd v. Anthony William O' Brien & Anor [1988] 1 MLRH 627). Indeed, if the defendants had candidly acknowledged their negligence earlier, than Nurul Husna's parents could have taken legal advice much earlier and kept copies of their bills and receipts to support their claim. In this regard, I accept that it would be unrealistic to expect Nurul Husna's parents have copies of bills and receipts for all of the expenses."

[Emphasis Added]; and

(3) in the Singapore High Court case of STU v. The Comptroller Of Income Tax [1962] 1 MLRH 229, at p 231, Tan Ah Tah J gave the following judgment-

"In this case certain explanations given by the appellant to the officers of the Income Tax Department were rejected on the ground that there was no documentary evidence to support them. No doubt documentary evidence can in many cases be very cogent and convincing. The lack of it however, should not invariably be a reason for rejecting an explanation. Not every transaction is accompanied or supported by documentary evidence. Much depends on the facts and circumstances of the case, but if the person who is giving the explanation appears to be worthy of credit does not reveal any inconsistency and there is nothing improbable in the explanation, it can, in my view, be accepted."

[Emphasis Added]

[40] Even though there is no rule of law for a trial court to give a discount on an award of damages when a claimant only adduces oral testimony in support of the award, in the interest of justice, the trial court has a discretion to give a fair and reasonable reduction or discount with regard to an award of damages [Discount (Damages)]. If the trial court does give a Discount (Damages), it is incumbent on the trial court to give reason(s) for the Discount (Damages) [Reason(s) (Discount on Damages)]. If there is/are no Reason(s) (Discount on Damages) for a particular award of damages, the award may be the subject matter of an appeal.

N(4). Can The Plaintiff Recover Special Damages For The Holidays Of Her Children?

[41] I am of the view that the High Court's award of special damages of RM600.00 for the holidays of the Plaintiff's children was too remote to be recovered in this case. This was because the deprivation of holidays for the children of the Plaintiff was not reasonably foreseeable due to the Trial Court's Factual Finding (Negligence of 2nd, 3rd, and 7th to 12th Defendants). As such, this award is set aside.

N(5). Whether The Court Can Refuse To Grant Damages (Cost Of Future Medical Treatment) On The Ground That Such Medical Treatment Is Available For Free In Government Hospitals/Clinics

[42] Our Federal Court has decided in Inas Faiqah, at [31] to [37], as follows:

"Medical care and hospital treatment

[31] The appellant sought for the cost of medical treatment at a private hospital and claimed for a sum of RM4,200.00 per year. The learned trial judge however allowed only one-third of the claim at RM1,033.00 per year after finding that the grounds advanced by the appellant were not sufficient to justify the appellant for full cost in opting for private medical treatment. The learned trial judge reasoned, inter alia, that the types of treatment sought by the appellant are available at the public hospital; that the appellant's father who was a retired teacher would be able to obtain facilities provided by the public hospital; that the long wait was not a sufficient proof of nonaccess; and the increasingly better medical services provided in the public hospital.

[32] The Court of Appeal affirmed the award made under this head of claim by the learned trial judge and held that the order of the learned trial judge was in line with the principle laid down in Chai Yee Chong v. Lew Thai [2004] 1 MLRA 195 and Gleneagles Hospital (KL) Sdn Bhd v. Chung Chu Yin & Ors And Another Appeal [2013] 5 MLRA 114.

[33] Learned counsel for the appellant submitted that the Court of Appeal was in error in saying that the learned trial judge had acted in line with the principle laid down in the above two cases in awarding only one-third of the appellant's claim for cost of future medical treatment, when in fact there is no such principle. It was contended that Chai Yee Chong concerned a claim for past private medical treatment and therefore is not relevant to the present case. Further, it was submitted that there were discussions in Chai Yee Chong of a practice of allowing only one-third of past private medical treatment expenses but that practice was not made a principle as understood by the Court of Appeal.

[34] The appellant argued that the Court of Appeal was also in error in this case in not following its earlier decision in Gleneagles as regards future private medical treatment whereby the full cost of future private medical treatment was allowed, subject to a reduction of 30%, after taking into account factors such as advance lump sum payment and the contingencies of life in the future. In contrast, the appellant argued that the Court of Appeal had in fact misunderstood its own earlier decision in Gleneagles when holding that the court had granted one-third of the amount claimed for future medical treatment in that case without considering the fact that 70% of the full future cost was allowed.

[35] Learned senior federal counsel for the respondent argued that the application of 'one-third practice' as propounded in Chai Yee Chong is not limited to only the cost of private medical treatment which has been incurred', but such practice was followed by a number of cases including Gleneagles. It was submitted that evidence must be led at trial to address on the appellant's needs and in the absence of such evidence, the court should dismiss the claim altogether or award a sum not exceeding one-third of the amount claimed. In this case, it was argued that the appellant merely made an assumption of the cost of future medical treatment at the private hospital and as such the learned trial judge had correctly allowed only one- third of the amount claimed, which the learned judge felt was a reasonable amount.

[36] ...In determining a claim for future medical treatment, be it at a private, or at a public hospital, the question of reasonableness in making such a claim should always be the paramount consideration. The plaintiff not only needs to justify, for instance, why he chooses treatment at a private hospital over a public one, but he must also show that the amount claimed for such treatment is reasonable. Of course this can be satisfied by the production of compelling evidence for that purpose. It is to be noted that in claiming for the cost of future damage in Gleneagles, evidence was led as to the cost of rehabilitation care of the 1st respondent and the costing was obtained from the private hospitals/centres.

[37] Nevertheless, in the present case, we found that the learned trial judge had considered the reasons advanced by the appellant in claiming for the cost for future medical treatment at the private hospital and was not persuaded to award the full cost claimed by the appellant. The learned trial judge had given her reasons for awarding only one-third of the amount claimed by the appellant. We affirm the award made by the learned trial judge in this respect, but on a different ground. We found that the amount awarded by the learned trial judge was fair and reasonable, and we do not find any justification to disturb the same."

[Emphasis Added]

[43] It is clear from Inas Faiqah that with regard to the court's award of Damages (Cost of Future Medical Treatment)-

(1) the court should award a "fair and reasonable" sum of Damages (Cost of Future Medical Treatment) [Fair and Reasonable Sum (Cost of Future Medical Treatment)]; and

(2) in assessing what is a Fair and Reasonable Sum (Cost of Future Medical Treatment)-

(a) the court may consider the fact that the future medical treatment needed by a patient (Future Medical Treatment) is available for free in Government Hospitals/Clinics; and

(b) if the Future Medical Treatment is available for free in Government Hospitals/Clinics-

(i) the court may decline to award any Damages (Cost of Future Medical Treatment); or

(ii) the court may award a Fair and Reasonable Sum (Cost of Future Medical Treatment) based on the cost of the Future Medical Treatment in private hospitals and clinics [Cost (Future Treatment in Private Hospitals/Clinics)]. Needless to say, a patient bears the evidential burden to adduce evidence regarding the Cost (Future Treatment in Private Hospitals/Clinics).

If the court's award of Damages (Cost of Future Medical Treatment) is based on the Cost (Future Treatment in Private Hospitals/Clinics), the court may grant a Discount (Damages) which is fair and reasonable (due to the fact that the Medical Treatment is available for free in Government Hospitals/Clinics).

[44] Premised on Inas Faiqah-

(1) I accept the contention by the learned SFC that the Plaintiff's future medical consultations, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, contracture release surgery and hospital admission for respiratory infection are available free of charge in Government Hospitals/Clinics;

(2) the learned High Court Judge had awarded cost of future medical consultations, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, contracture release surgery and hospital admission for respiratory infection as follows-

(a) cost of consultation with a dentist, respiratory physician and gastroenterologist — RM19,000.00;

(b) cost of consultation with a rehabilitative physician — RM15,200.00;

(c) cost of consultation with a neurologist — RM3,450.00;

(d) physiotherapy — RM197,600.00;

(e) occupational therapy — RM197,600.00;

(f) speech therapy — RM3,450.00;

(g) contracture release surgery — RM4,000.00; and

(h) hospital admission for respiratory infection — RM57,000.00.

Notwithstanding the fact that the Plaintiff's future medical consultations, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, contracture release surgery and hospital admission for respiratory infection can be obtained for free in Government Hospitals/Clinics, it is fair and reasonable to reduce the above awards by the High Court as follows-

(i) cost of consultation with a dentist, respiratory physician and gastroenterologist — RM7,000.00;

(ii) cost of consultation with a rehabilitative physician — RM6,000.00;

(iii) cost of consultation with a neurologist — RM2,000.00;

(iv) physiotherapy — RM100,000.00;

(v) occupational therapy — RM100,000.00;

(vi) speech therapy — RM2,000.00;

(vii) contracture release surgery — RM2,000.00; and

(viii) hospital admission for respiratory infection — RM40,000.00.

N(6). Whether Certain Items Of The High Court's Decision (Quantum) Were "So Extremely High" So As To Attract Appellate Intervention

[45] The following items in the High Court's Decision (Quantum) were "so extremely high" and appellate intervention is therefore warranted:

(1) Special damages from 12 December 2013 to 7 December 2015 (23 months)]

(a) a sum of RM67,841.00 had been awarded by the High Court as special damages for travelling and accommodation expenses incurred by the Plaintiff's husband. However, no documentary evidence was adduced by the Plaintiff to support this award. This amount of RM67,841.00, in my view, was "so extremely high". The learned SFC had proposed a sum of RM23,000.00. I decide that an amount of RM25,000.00 would constitute a fair and reasonable sum of compensation for this claim;

(b) the learned High Court Judge had awarded RM80,500.00 as the value of care provided to the Plaintiff by the Plaintiff's family members [based on a sum of RM3,500.00 per month (for 23 months)]. It is clear to us that this amount is "so extremely high". The learned SFC's proposal of RM58,000.00 (RM2,500.00 per month X 23 months) was fair and reasonable. Hence, the reduction of this award of special damages to RM58,000.00;

(c) an award of RM8,050.00 had been granted by the High Court for cost of nutritional supplements, special food and vitamins for the Plaintiff (RM350.00 per month X 23 months). No receipt or documentary proof had been adduced by the Plaintiff to support this award.

With regard to the above award, according to the Federal Court in Inas Faiqah, at [55]-

[55] It was argued that the appellant would require specially prepared food and nutrition for the rest of her life and therefore the award in the sum of RM400.00 per month was proposed by the appellant for this claim. The learned trial judge dismissed this claim as she found that there was no evidence to support the appellant's contention that the appellant would need any special food and nutrition. The learned trial judge also reasoned that regardless of the appellant's condition, the appellant's father would surely have to provide healthy food for their family members. We affirm the learned trial judge's finding on this award."

[Emphasis Added]

The above award was "so extremely high" and I substitute this amount of special damages with a fair and reasonable sum of RM3,000.00 (as proposed by the learned SFC);

(d) the learned High Court Judge had awarded an amount of RM32,150.00 (for 23 months) as the value of care provided by the Plaintiff to her children and family (as previously provided by the Plaintiff before the Plaintiff's Brain Damage). This award of special damages was premised on a monthly value of RM1,397.82. The learned SFC submitted that a sum of RM11,000.00 should be reasonable compensation for the loss of value of care provided by the Plaintiff to her children and family.

In my view, the above award of RM32,150.00 was "so extremely high" because before the Plaintiff suffered brain damage in this case, she was working as an administrative executive and was not a full-time homemaker. A sum of RM800.00 per month would be a fair and reasonable compensation for the value of care provided by the Plaintiff to her children and family. Consequently, this head of special damages was reduced to RM18,400.00 (RM800.00 x 23 months); and

(e) in the Plaintiff's pre-trial discovery application (prior to the filing of This Suit), she had agreed to a sum of RM300.00 as costs for the pre-trial discovery application. Hence, the Plaintiff could not now claim RM7,420.00 as costs for obtaining medical records in this case. Such an amount of RM7,420.00 was "so extremely high" and should be substituted with a sum of RM1,000.00 (as proposed by the learned SFC);

(2) Pre-trial damages [from 7 December 2015 (date of filing of This Suit) to 15 April 2021 (date of the High Court's Decision), a total of 63 months!

(a) the High Court awarded an amount of RM18,900.00 for travelling expenses (RM300.00 per month X 63 months). No documentary proof had been adduced to support this award. The learned SFC submitted that a sum of RM6,000.00 should only be awarded. In my view, this award of RM18,900.00 was "so extremely high". Hence, this award is substituted with an amount of RM10,000.00 as a fair and reasonable compensation for the Plaintiff;

(b) a sum of RM220,500.00 had been given by the learned High Court Judge as the value of care provided to the Plaintiff by her family members (based on an amount of RM3,500.00 X 63 months).

The Federal Court had decided in Inas Faiqah, at [45], as follows:

"[45] It can be seen from the evidence of the appellant's mother that if not for the imposing necessity to take care of the appellant, she would not have ceased her study and might have possibly pursued her diploma, and hence have a better opportunity to develop her career. Tending to the appellant is also exhausting and stressful whereby the appellant's mother had to wake up at night to attend to the appellant. We are of the respectful view that the award of RM300.00 per month made by the High Court was erroneous in the circumstances and we feel that an award of RM500.00 per month would be a fair and reasonable amount in the circumstances of the case and in accord with other comparable cases."

[Emphasis Added]

This award of RM220,500.00 was "so extremely high" because a sum of RM2,500.00 per month as the value of care provided to the Plaintiff by her family members should suffice as a fair and reasonable compensation for the Plaintiff. Consequently, we reduce this award to RM157,500.00 (RM2,500.00 X 63 months); and