Federal Court, Putrajaya

Hasnah Mohammed Hashim CJM, Zabariah Mohd Yusof, Hanipah Farikullah FCJJ

[Civil Appeal Nos: 01(i)-12-05-2025(W) & 01(i)-13-05-2025(W)]

13 August 2025

Civil Procedure: Judicial review — Appeal against Court of Appeal's order allowing respondent's appeal against High Court's decision dismissing respondent's application for leave for judicial review, and order allowing respondent's application to adduce additional evidence — Respondent granted royal pardon and sought mandamus order to compel appellant to confirm existence of Addendum Order for respondent to serve reduced term of imprisonment under house arrest — Whether leave required to introduce new evidence at appellate stage in Court of Appeal and Federal Court — Whether application for leave for judicial review interlocutory in nature — Whether respondent satisfied requirements of r 7 of Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 ('RCA 1994') to admit new evidence — Whether principles established in Ladd v. Marshall codified or merely reflected in r 7(3A) RCA 1994

The respondent, a serving prisoner, had applied for and was granted a pardon on 29 January 2024 by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong XVI ('YDPA'), and his sentence of 12 years' imprisonment and a RM210 million fine was reduced to 6 years' imprisonment and a fine of RM50 million ('Pardons Order'). The respondent subsequently, on 12 February 2024, claimed to have received reliable information that in addition to the Pardons Order, a supplementary order dated 29 January 2024 ('Addendum Order') was issued by the YDPA for him to serve his reduced sentence under house arrest instead of being confined in the Kajang Prison or any other prison. The respondent thereafter applied for leave for judicial review, seeking mandamus orders to compel the appellant to confirm the existence of the Addendum Order and provide him with a copy thereof, together with a copy of the Pardons Order, and for him to serve the remainder of his sentence under house arrest at his residence. The High Court Judge ('HCJ') dismissed the application on the grounds, inter alia, that: (i) the source of the information contained in the affidavits relied on by the respondent had not affirmed an affidavit on his behalf; (ii) there was no arguable case for further investigation at the substantive stage; and (iii) the criteria for grant of mandamus was not met. The respondent appealed to the Court of Appeal against the said decision, and two days prior to the hearing of the appeal, he filed a notice of motion ('encl 26') to introduce new evidence, which included, inter alia, the Addendum Order. Thereafter, another notice of motion ('encl 50') was filed by the respondent, seeking leave to include additional new evidence. The majority of the Court of Appeal allowed encl 26 but dismissed encl 50, which meant that the respondent was granted leave for the judicial review, and the admission of the Addendum Order was allowed. The majority further held that the application for leave in a judicial review proceeding fell within the provisions of s 69(2) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 and r 7(2) of the Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 ('RCA 1994'), and therefore, the Addendum Order that was sought to be adduced as new evidence after the decision of the HCJ, did not require leave of court. The minority however, held otherwise in that although such a leave application was interlocutory in nature, the refusal of leave had a final effect as it prevented the respondent from proceeding to the hearing of the substantive judicial review application. The minority was also of the view that r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 codified the principle in Ladd v. Marshall, that the respondent had failed to meet one of the elements of Ladd v. Marshall, namely, by failing to exercise reasonable diligence in obtaining new evidence, ie the Addendum Order. Hence the instant appeals by the appellant in which the following questions of law were raised, namely: (i) whether the principles established in Ladd v. Marshall had been codified or merely reflected in r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 (Question 1); (ii) whether r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 rendered the principles in Ladd v. Marshall concerning the admission of fresh or additional evidence in the Court of Appeal no longer applicable (Question 2); (iii) whether r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 imposed a higher threshold on parties seeking to introduce fresh or additional evidence by requiring proof of a 'determining influence, which exceeds the important influence' threshold established in Ladd v. Marshall (Question 3); (iv) at the leave stage for judicial review proceedings, whether the burden of proof regarding the existence of disputed fresh or additional evidence lay with the Attorney General ('AG') in his capacity when acting solely under O 53 r 3(3) of the Rules of Court 2012 ('ROC 2012') (Question 4); (v) at the leave stage for judicial review proceedings, whether there was any legal obligation to compel any authority to confirm the existence of, and provide copies of documents to the applicant, particularly with respect to the AG, who was acting solely in his capacity under O 53 r 3(3) of the ROC 2012. (Question 5); (vi) at the leave stage for judicial review proceedings, whether there was a distinction in the role and obligations of the AG when acting solely in his capacity under O 53 r 3(3) of the ROC 2012 as opposed to when acting as a respondent, particularly in the context of the duty to confirm the existence and/or admissibility of fresh or additional evidence. If such a distinction existed, what was the dividing line between these two roles?; (Question 6); and (vii) in judicial review proceedings, whether the applicant could introduce fresh or additional evidence that would have the legal effect of directly or indirectly challenging the decision of the Pardons Board (Question 7). The arguments and issues raised pertained to whether leave ought to be granted for the judicial review application and whether an application for leave for judicial review was interlocutory in nature in the context of r 7(2) of the RCA 1994.

Held (dismissing both appeals; ordered accordingly):

(1) The application for leave in judicial review proceedings in this case was not an interlocutory proceeding for the purpose of r 7(2) of the RCA 1994; therefore, leave was required. Such an application, although interlocutory in form, was an application to decide on the rights of the parties. Hence, as regards evidence, it should not be regarded as an interlocutory proceeding within the meaning of O 41 r 5(2) of the ROC 2012. (para 46)

(2) The use of the word 'may' in the phrase fresh evidence 'may be given without leave' in r 7(2) of the RCA 1994 suggested that the court retained a discretion to allow such evidence to be adduced but that did not mean that the court must invariably allow such evidence to be adduced without leave, without some kind of filtering mechanism. (paras 47-50)

(3) Important evidence might and would usually also be determinative evidence, but the fact that it was of great value might not be the deciding factor in the matter. At the appellate level when the 'determining influence' test in r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 came into play, notwithstanding the different semantics, 'important influence' was comparable to 'determining influence' because at that level, the only evidence in question was that particular piece of evidence sought to be adduced and whatever the label applied, the effect would necessarily be determinative of the outcome on the case at the lower court. Practically speaking and in reality, the demarcation between 'important' and 'determining' under r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 was of no consequence at the appellate level. (paras 76-80)

(4) The judicial process undertaken in both Ladd v. Marshall and r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 remained effectively the same in substance and purpose because the words 'if true' in r 7(3A)(b) of the RCA 1994 directed the court to assess the 'likely influence' of the new evidence on the outcome, assuming it was truthful, and the words 'if given' in Ladd v. Marshall required the court to consider what influence the evidence would have had if presented at the trial. (paras 83-86)

(5) While the Ladd v. Marshall conditions remained apposite, they should not be construed as strictly as though they had statutory or legislative force, but rather, should be treated as a set of guidelines to be adapted as the interests of justice would require according to the circumstances of a particular matter in accordance with the legislative regimes, ie r 7 of the RCA 1994. The Ladd v. Marshall criteria served as useful interpretive tools when judges gave legal effect to the provisions of the said rule. (para 91)

(6) On the facts, the 1st condition of r 7(3A)(a) of the RCA 1994, namely, that the new evidence was not available to the respondent, had been fulfilled. Apart from the relentless and repeated attempts to obtain the Addendum Order by the respondent, the issue of the sensitive nature of the Addendum Order and strict protocol involving the Palace, the respondent had also satisfied the 2nd condition of r 7(3A)(a) of the RCA 1994 on 'reasonable diligence'. The minority of the Court of Appeal erred in fact in this respect in ruling that the reasonable diligence element was not fulfilled. (para 97)

(7) The issue of whether the Addendum Order was 'true' or not was an arguable point to be ventilated in the substantive hearing of the judicial review application. In the circumstances, the respondent had satisfied the elements of r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 to allow the Addendum Order to be admitted as new evidence to be used at the substantive hearing of the judicial review application. (paras 103, 104 & 108)

(8) Rule 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 was the statutory provision with regard to the admission of new evidence at the appellate level. Although the exact wording of the essential elements in Ladd v. Marshall and the elements in r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 were not word-for-word the same, the effect and consequence of applying the elements in r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 and those in Ladd v. Marshall, led to the same conclusion. (para 107)

(9) In the circumstances, the answer to Question 1 was that r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 encapsulated, ie expressed the essential features of the test in Ladd v. Marshall succinctly. The answers to Questions 2 and 3 were in the negative. Given the concession by the AG as to the existence of the Addendum Order, Questions 4 to 6 were considered hypothetical, academic and did not need to be answered. Question 7, which related to the challenge against the decision of the Pardons Board, was to be addressed at the substantive stage of the judicial review proceedings, if necessary. (para 108)

Case(s) referred to:

Al-Koronky v. Time Life Entertainment Group [2006] EWCA Civ 1123 (refd)

Al-Sadeq v. Dechert LLP [2024] EWCA Civ 28 (refd)

Anan Group (Singapore) Pte Ltd v. VTB Bank (Public Joint Stock Co) [2019] SGCA 41 (refd)

Chai Yen v. Bank Of America National Trust & Savings Association [1980] 1 MLRA 578 (refd)

Gilbert v. Endean [1878] 9 Ch D 259 (refd)

Hamilton v. Al-Fayed (No 2) [2001] EMLR 15 (refd)

Hertfordshire Investments Ltd v. Bubb And Another [2000] 1 WLR 2318 (refd)

Juraimi Husin v. Pardons Board Of State Of Pahang & Ors [2002] 2 MLRA 121 (refd)

Ladd v. Marshall [1954] 3 All ER 745 (folld)

Lau Foo Sun v. Government Of Malaysia [1970] 1 MLRA 219 (refd)

Ng Hee Thoong & Anor v. Public Bank Berhad [1995] 1 MLRA 48 (refd)

OpenNet Pte Ltd v. Info Communications Development Authority Of Singapore [2013] 2 SLR 880 (refd)

PP v. Soon Seng Sia Heng & 9 Other Cases [1979] 1 MLRA 384 (refd)

R (On The App. Of Yasser-Al Siri) v. Secretary of State For The Home Department [2021] EWCA Civ 113 (refd)

Re EChildren: Reopening Finding Of Fact [2020] 2 All ER 539 (refd)

Rossage v. Rossage And Others [1960] 1 WLR 249 (refd)

Singh v. Habib [2011] EWCA Civ 599 (refd)

Terluk v. Berezovsky [2011] EWCA Civ 1534 (refd)

Tuan Sarip Hamid & Anor. v. Patco Malaysia Berhad [1995] 1 MLRA 536 (refd)

V Medical Services M Sdn Bhd v. Swissray Asia Healthcare Sdn Bhd [2025] 3 MLRA 360 (refd)

Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council v. Secretary Of State For Communities And Local Government [2011] 2 AC 304 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Civil Procedure Rules 1998 [UK], r 52.21(2)

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, s 69(2), (3)

Federal Constitution, art 42(4)(b), (5), (8)

Rules of Court 2012, O 41 r 5(2), O 53 r 3, O 55 r 7

Rules of Court 2021 [Sing], O 18 r 8(6)

Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994, r 7(1), (2), (3A)(a), (b)

Rules of the Federal Court 1995, r 3

Rules of the Supreme Court [UK], O 38 r 3

Supreme Court of Judicature Act 2007 [Sing], s 59(4), (5)

Supreme Court Rules 2024 [UK], Practice Direction 5.11

Counsel:

For the appellant: Mohd Dusuki Mokhtar (Shamsul Bolhassan, Ahmad Hanir Hambaly @ Arwi, Nurhafizza Azizan, Safiyyah Omar, Ainna Sherina Saipolamin & Siti Nurfarhana Muhammad Azmi with him); AG's Chambers

For the respondent: Muhammad Shafee Abdullah (Muhammad Farhan Muhammad Shafee, Wan Muhammad Arfan Wan Othman, Nur Syafiqah Mohd Sofian, Naresh Mayachandran, Tharrence Anthony (PDK) & Mohd Hafeez Rahim (PDK) with him); M/s Shafee & Co

[For the Court of Appeal judgment, please refer to Dato' Seri Mohd Najib Tun Hj Abd Razak v. Menteri Dalam Negeri & Ors [2025] 5 MLRA 901]

JUDGMENT

Zabariah Mohd Yusof FCJ:

[1] There are 2 appeals by the learned Attorney General of Malaysia before us, namely:

(i) Civil Appeal No 01(i)-12-05/2025(W):

— Appeal against the entirety of the majority decision of the Court of Appeal dated 6 January 2025 which allowed the respondent's appeal and set aside the entire decision of the High Court Judge dated 3 July 2024, which dismissed the application for leave for Judicial Review, with no order as to cost; and

(ii) Civil Appeal No 01(i)-13-05/2025(W):

— Appeal against the entirety of the majority decision of the Court of Appeal dated 6 January 2025, that allowed the respondent's application in encl 26 (application to adduce additional evidence) dated 3 December 2024 at the Court of Appeal with no order as to costs.

[2] The 2 Appeals before us are premised upon the following Questions of law:

"(1)Whether the principles established in Ladd v. Marshall [1954] 3 All ER 745 ("Ladd v. Marshall") have been codified or merely reflected in r 7(3A) of the Rules of Court of Appeal 1994 ("RCA 1994");

(2) Whether r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 renders the principles in Ladd v. Marshall concerning the admission of fresh or additional evidence in the Court of Appeal no longer applicable;

(3) Whether r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 imposes a higher threshold on parties seeking to introduce fresh or additional evidence by requiring proof of a "determining influence, "which exceeds the "important influence" threshold established in Ladd v. Marshall;

(4) At the leave stage for judicial review proceedings, whether the burden of proof regarding the existence of disputed fresh or additional evidence lies with the Attorney General (AG) in his capacity when acting solely under O 53 r 3(3) of the Rules of Court 2012;

(5) At the leave stage for Judicial Review proceedings, whether there is any legal obligation to compel any authority to confirm the existence of and provide copies of documents to the Applicant, particularly with respect to the AG, who is acting solely in his capacity under O 53 r 3(3) of the Rules of Court 2012;

(6) At the leave stage for Judicial Review proceedings, whether there is a distinction in the role and obligations of the Attorney General when acting solely in his capacity under O 53 r 3(3) of the Rules of Court 2012 as opposed to when acting as a Respondent, particularly in the context of the duty to confirm the existence and/ or admissibility of fresh or additional evidence. If such a distinction exists, what is the dividing line between these two roles?

(7) In Judicial Review proceedings, whether the Applicant may introduce fresh or additional evidence that would have the legal effect of directly or indirectly challenging the decision of the Pardons Board."

[3] The proposed Questions 1, 2, 3 and 7 relate to the issue of admission of fresh or additional evidence. While the proposed Questions 4, 5 and 6 relate to the issue of the role of the Attorney General in Judicial Review Proceedings.

Background Facts

[4] The respondent is a serving prisoner who had applied for a complete/ full pardon from His Majesty Seri Paduka Baginda Yang DiPertuan Agong XVI (the YDPA XVI) on 1 September 2022 pursuant to art 42 of the Federal Constitution, after exhausting his legal rights until the Federal Court. The Federal Court had affirmed his conviction and sentence of 12 years of imprisonment and fined RM210 million for the SRC case on 8 December 2021.

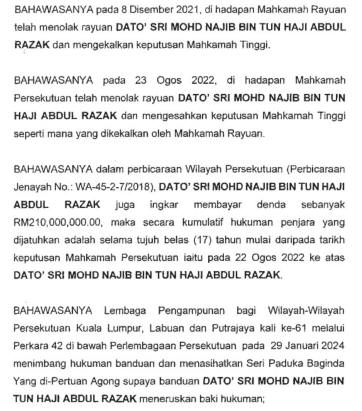

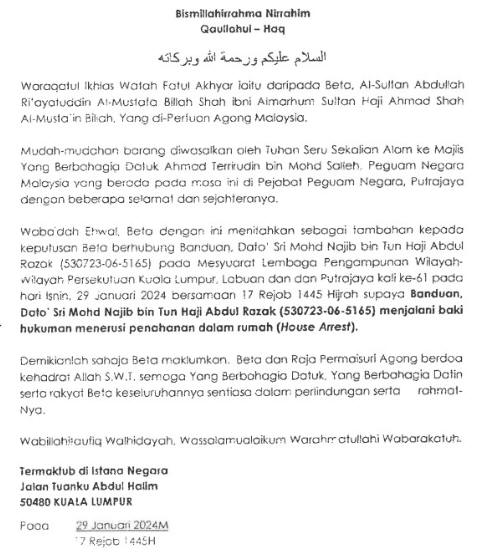

[5] On 2 February 2024, the Pardons Board under the purview of the Minister in the Prime Minister's Department (Law and Institutional Reform) and Director General of Legal Affairs Division of the Prime Minister's Department announced by way of media statement after considering the views and advice of the Pardons Board, that the YDPA had granted the respondent a pardon by reducing the imprisonment sentence to 6 years and a fine reduced to RM 50 million (hereinafter referred to as the "Pardons Order") which is as reproduced below:

Kepada:

Ketua Pengarah Penjara Malaysia

dan Sekalian Yang Menerima Surat Ini;

[6] On 12 February 2024, the respondent claimed to have received clear and reliable information that in addition to the Pardons Order dated 29 January 2024, the YDPA had issued a supplementary order (hereinafter referred to as "the Addendum Order") which states that the respondent is to serve a reduced sentence of his imprisonment under condition of home arrest, instead of being confined in Kajang Prison or any other prison.

[7] The respondent instructed his solicitors to confirm the details of the Addendum Order with the learned Attorney General (AG) by way of a letter dated 14 February 2024, which was copied to the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister.

[8] By 22 March 2024, the matter had reached the Minister of Home Affairs regarding, inter alia, the existence of the Addendum Order. The matter was also brought to the attention of the Pardons Board for the Territories of Kuala Lumpur, Labuan and Putrajaya, as well as the Minister in the Prime Minister's Department (Law and Institutional Reform) and Director General of Legal Affairs Division in the Prime Minister's Department on 29 March 2024.

[9] Thereafter, in April 2024, the respondent filed an application for leave for Judicial Review under O 53 of the Rules of Court 2012 seeking mandamus orders to compel the appellant to do the following acts:

(i) To confirm the existence of the Addendum Order dated 29 January 2024 which provided that the respondent is to serve a reduced term of imprisonment under house arrest;

(ii) To provide the respondent with a copy of the Pardons Order and the Addendum Order dated 29 January 2024; and

(iii) Consequently, the respondent is to serve the remainder of the prison sentence under house arrest at his residence in Kuala Lumpur.

[10] The learned AG appeared and opposed the Judicial Review application premised on the ground that the pre-requisites for mandamus were not fulfilled and the test for leave for Judicial Review was not satisfied.

[11] The learned High Court Judge dismissed the application for leave for Judicial Review on 3 July 2024, premised essentially on, inter alia:

(i) the source (of the information contained in the affidavits relied upon by the respondent), Tengku Zafrul did not affirm any affidavit on behalf of the respondent. There was no explanation as to why this is so. The source was available but was not used. The application at the leave stage was an ex parte application and the test was to peruse the material produced by the applicant then (who is the respondent in the present appeal) to see whether an arguable case had been made out, for the matter to proceed to the substantive stage of the hearing of the Judicial Review application;

(ii) Tengku Zafrul sought to file an affidavit to correct some inaccuracies in the affidavit of Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, however it was objected to, by the respondent. The reliability of the hearsay evidence in the affidavits could not be judged and therefore no weight was placed on the said affidavits. It was held by the learned High Court Judge that there was no arguable case for further investigation at the substantive stage; and

(iii) The criteria for the granting of mandamus was not met. The respondent did not show any failure on the part of the appellant, in particular the Pardons Board to perform the statutory duties imposed upon them in law.

[12] On 19 December 2024, the respondent's solicitors also requested for the original copy of the Pardons Order from the Kajang Prison.

Court of Appeal Proceedings

[13] Aggrieved by the decision of the High Court, the respondent appealed to the Court of Appeal. Two days before the hearing at the Court of Appeal, on 3 December 2024, the respondent filed a Notice of Motion to introduce new evidence, which, amongst others, included the Addendum Order (encl 26).

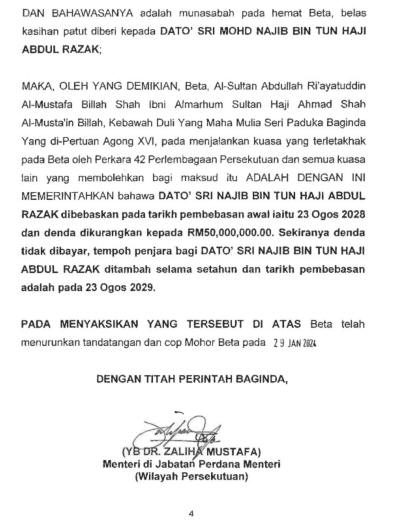

[14] The Addendum Order that the respondent sought to be admitted as new evidence reads as follows:

[15] Subsequently, the respondent filed another Notice of Motion to amend encl 26 and include additional new evidence (encl 50). Enclosure 50 essentially seeks the Court to grant leave to the respondent to adduce additional evidence (in the event that leave is required) in the form of the affidavits by Mohamad Nizar dated 2 December 2024 and the affidavit No. 2 dated 5 January 2025, the Addendum Order and a protective order to safeguard the confidentiality of the additional evidence.

[16] On 6 January 2025, the Court of Appeal, by a majority, allowed the appeal by allowing encl 26 but dismissed encl 50.

[17] The grounds of the majority decision of the Court of Appeal held that the fact that there is no rebuttal affidavit from the appellant challenging the existence and the authenticity of the Addendum is rather compelling. The majority applied the principle in Ng Hee Thoong & Anor v. Public Bank Berhad [1995] 1 MLRA 48. Whereas the minority decision held that r 7(3A) of the Rules of Court of Appeal 1994 codifies the principle of Ladd v. Marshall and that the respondent failed to meet one of the elements of Ladd v. Marshall, namely the failure to exercise reasonable diligence in obtaining the new evidence, i.e the Addendum Order. However, the minority agree that the new evidence, if true, would have a determining influence on the decision of the High Court. It is incumbent on the respondent to fulfil all the elements of Ladd v. Marshall to admit the new evidence.

[18] The Court of Appeal (by the majority decision) allowed the appeal, which means leave is granted for the Judicial Review application and allowed the admission of the Addendum Order. Consequently, the Court of Appeal directed the matter to be remitted to the High Court for the hearing of the substantive Judicial Review application before another High Court Judge.

Analysis And Findings Of This Court

[19] Before we proceed to answer the Questions posed, it is pertinent to note that in the midst of submissions by the learned AG before us, there was a concession made by the learned AG that the Addendum Order exists.

[20] This concession has a great impact on the Questions posed before us, in particular the Questions relating to the existence of the disputed new evidence. With this concession, Questions 4, 5 and 6 are no longer relevant and are academic. Hence, we will not deal with those questions here.

[21] Be that as it may, although there was a concession with regard to the existence of the purported Addendum Order, we need to emphasise that:

• Firstly, it is not our judgment herein that the Addendum Order is part of the Pardons Order and neither are we saying that it is not. It is premature at this stage for this Court to make such a determination.

• Secondly, despite the existence of the Addendum Order, that by itself, does not translate into automatic admissibility of the same. The respondent still has to satisfy the rule and criteria as to the admission of the Addendum Order as new evidence, which we will address accordingly in our judgment.

• Thirdly, the existence of the Addendum Order does not automatically render the Addendum Order as valid. This issue would have to be determined at the substantive hearing in the Judicial Review proceedings, if leave is granted. In this context art 42 of the Federal Constitution takes center stage, namely:

• Article 42 of the Federal Constitution governs the royal prerogative of mercy, whereby the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (YDPA) is empowered to grant pardons, reprieves, and respites in respect of all offences committed in the Federal Territories of Kuala Lumpur, Labuan, and Putrajaya.

• The exercise of such clemency by the YDPA is not absolute. It is to be carried out in accordance with the constitutional limits prescribed by art 42, particularly through the framework of advice and procedure embedded therein.

• Pursuant to art 42(4)(b), the YDPA is required to act on the considered advice of the Pardons Board for the Federal Territories. His function in the clemency process is therefore inextricably tied to the deliberations and recommendations made by the Board established for that purpose.

• The Pardons Board for the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur is constituted under art 42(5) of the Federal Constitution, and comprises the learned AG, the Prime Minister, and three other members appointed by the YDPA.

• Article 42(8) further mandates that any meeting of the Pardons Board must be held in the presence of the YDPA, who shall preside over its proceedings. This requirement is both procedural and constitutional in nature.

• Any failure to adhere strictly to the procedural safeguards and substantive requirements under art 42 will render the entire clemency process susceptible to constitutional challenge and Judicial Review.

• Fourthly, on the issue of justiciability, that is also to be addressed and determined at the substantive hearing, if leave is granted.

[22] The arguments and the issues raised in the appeals before us are to determine whether leave ought to be granted for the Judicial Review application.

Questions 1, 2, 3, And 7

[23] We will now address the remaining Questions, which are Questions 1, 2, 3, and 7. These questions relate to the admission of new evidence at the appellate level.

[24] The applicable statutory provision with regard to the admission of new evidence at the appellate level is r 7 of the Rules of the Court of Appeal 1994 (RCA 1994), which provides that:

"(1) The Court shall have all the powers and duties, as to amendment or otherwise, of the appropriate High Court, together with full discretionary power to receive further evidence by oral examination in Court, by affidavit, or by deposition taken before an examiner or Commissioner.

(2) Such further evidence may be given without leave on interlocutory applications, or in the case as to matters which have occurred after the date of the decision from which the appeal is brought.

(3) Upon appeals from a judgment, after trial or hearing of any cause or matter upon the merits, such further evidence, save as to matters subsequent as aforesaid, shall be admitted on special grounds only, and not without leave of the Court.

(3A) At the hearing of the appeal further evidence shall not be admitted unless the Court is satisfied that-

(a) at the hearing before the High Court or the subordinate court, as the case may be, the new evidence was not available to the party seeking to use it, or that reasonable diligence would not have made it so available; and

(b) the new evidence, if true, would have had or would have been likely to have had a determining influence upon the decision of the High Court or the subordinate court, as the case may be."

[25] Rule 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 is substantially identical to s 69(3) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964, with the exception of the provision of r 7(3A), which is not present in s 69(3) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964.

[26] The majority panel of the Court of Appeal erred when it relied on O 55 r 7 of the Rules of Court 2012 as being the principles applicable to adduce new evidence at the Court of Appeal (see para 20 of the Majority grounds of judgment). Order 55 r 7 of the ROC 2012 is expressly confined to proceedings before the High Court, in the context of appeals from the subordinate courts to the High Court. It is not applicable to an application to adduce fresh or new evidence at the appellate stage in the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court.

Whether Leave Is Required To Introduce New Evidence At The Appeal Stage

[27] Parties dispute as to whether this application for leave in a Judicial Review application is interlocutory in nature, in the context of r 7(2) of the RCA 1994. The said rule provides that "such further evidence may be given without leave in interlocutory applications...".

[28] The majority grounds of judgment of the Court of Appeal at paras [54] and [55] held that, appeal arising from the dismissal of leave for a Judicial Review application is interlocutory in nature. Therefore, the application for leave in a Judicial Review application falls squarely within the provisions of s 69(2) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 and r 7(2) RCA 1994. Hence, the Addendum Order, which was sought to be adduced as new evidence after the decision of the learned High Court Judge, need not require leave from the Court.

[29] The minority held otherwise, that although a leave application for the Judicial Review application is interlocutory in nature, a refusal of leave has a final effect as it prevents the applicant from proceeding to the hearing of the substantive Judicial Review application. The substantive Judicial Review hearing is what will determine the final rights or obligations. The leave stage only filters out unmeritorious cases. However, when the High Court dismissed the application for leave, that finally disposes of the entire Judicial Review proceedings, which had determined the rights of the parties, thus rendering it final in effect and thus is not interlocutory (see paras [45]-[47] of the minority judgment). The minority judgment further added that:

"[48] ...the affidavits filed in support of the leave application will be the same affidavit used for the substantive application (see O 53 r 4(2)). Order 53 r 3 (2) of ROC 2012 provides that an application for leave must be "supported by a statement setting out the name and description of the applicant, the relief sought and the grounds on which it is sought, and by affidavits verifying the facts relied on." Therefore, as opposed to O 41 r 5(2) of the ROC 2012, the affidavits affirmed for the purpose of judicial review application cannot be based on hearsay evidence."

[30] The learned High Court Judge and the appellant referred to the decision of the Supreme Court in Tuan Sarip Hamid & Anor v. Patco Malaysia Berhad [1995] 1 MLRA 536 at pp 538-539, which echoed the minority view on this matter, when it ruled as follows:

"We are supported in our views regarding the requirements of the application for leave and the affidavit in support thereof under O 53 r 1(2) by the following passages in the book Judicial Review by Michael Supperstone QC and James Goudie QC which we thoroughly approve of... On the last question whether hearsay material may be referred to in the affidavit in support of the application for leave, the learned authors have this to say at p 357 para 2, and we agree:

It is not entirely clear whether the affidavit in support of the application for leave should be regarded as interlocutory in character or otherwise. This has a possible significance in terms of whether hearsay material may strictly be admitted. The application for leave itself is undoubtedly interlocutory; however, if leave is granted, the affidavit in support of the leave application is served together with the notice of motion and forms the first basis of the applicant's case in the substantive application."

[Emphasis added]

[31] The appellant, in relying on the case of Tuan Hj Sarip Hamid, argued that, although it is trite that an application for leave to commence Judicial Review proceedings under O 53 of ROC 2012 is interlocutory in nature, the affidavit verifying facts in support thereof may not necessarily be so.

[32] Our analysis on whether the application for leave for Judicial Review in this case is interlocutory in nature is explained in the following paragraphs.

[33] Generally speaking, interlocutory applications do not determine the rights of the parties. Even after the disposal of an interlocutory application, the main suit, which is to determine the rights of the parties still persists.

[34] What we have before us is an application for leave for a Judicial Review application under O 53 r 3 of the ROC 2012. The application for leave here is an application to determine the right of the applicant to seek Judicial Review.

[35] Normally, a party would initiate an action in court for the determination of his rights or his claim. This determination by the Courts would be regulated by the rules of evidence and admissibility at the full hearing. In a normal Civil Suit, there may be interlocutory applications filed with affidavits in support. In such a situation, O 41 r 5(2) ROC 2012 applies to affidavits used in interlocutory proceedings, which are preliminary or temporary steps taken during a lawsuit before final judgment which disposes of parties' rights. This rule allows the flexibility for the inclusion of "statements of belief, providing the source and grounds for that belief".

[36] However, for applications or matters before the court which are not interlocutory in nature, such type of evidence is not admissible. In other words, although the application is interlocutory in form, it is not interlocutory within the meaning of O 41 r 5(2) of the ROC 2012 as regards evidence because it decides on the rights of the parties which are regulated by the rules of evidence and admissibility.

[37] We have asked parties whether there is an authority directly on point that decided that the application for leave in a Judicial Review is an interlocutory proceeding or vice versa, to which the answer is in the negative. In the course of our research, we found a decision of the English Court of Appeal, which had the occasion to deal with a similar issue in Gilbert v. Endean [1878] 9 Ch D 259, where Cotton LJ at pp 268-269 held:

"I agree in the opinion expressed by the other members of the Court, and I should add nothing but for the way under which the case comes before us. It comes to us on motion, but though it comes before us in that form, we have to decide the ultimate rights of parties, and in my opinion, as regards evidence, it ought to be dealt with just in the same way as if a bill had been filed. I am now adverting.......to the question whether the rule that on interlocutory applications the Court may act upon evidence given on the witness information and belief applies to the present case. But for the purpose of this rule those applications only are considered interlocutory which do not decide the rights of parties, but are made for the purpose of keeping things in status quo till the rights can be decided, or for the purpose of obtaining some direction of the Court as to how the cause is to be conducted, as to what is to be done in the progress of the cause for the purpose of enabling the Court ultimately to decide upon the rights of parties.........many of the cases which are brought before the Court on motions and on petitions, and which are therefore interlocutory in form, are not interlocutory within the meaning of that rule as regards evidence. They are to decide the rights of the parties and whatever the form may be in which such questions are brought before the Court, in my opinion the evidence must be regulated by ordinary rules, and must be such as would be admissible at the hearing of the cause."

[Emphasis added]

[38] Later, in another English Court of Appeal case in Rossage v. Rossage And Others [1960] 1 WLR 249, at p 251, which concerned divorce proceedings, where years after the divorce, the father made an application to suspend the right of access of the mother to the child of the marriage. The application was supported by certain affidavits consisting largely of scandalous imputations against the mother, premised upon hearsay and irrelevant matters. The mother applied to have these affidavits expunged from the file as being scandalous and irrelevant, and in breach of the O 38 r 3 of the Rules of the Supreme Court (RSC), which provides that:

"Affidavits shall be confined to such facts as the witness is able of his own knowledge to prove...Provided that on interlocutory proceedings...an affidavit may contain statements of information and belief, with the sources and grounds thereof."

[Emphasis added]

[39] The husband contended, inter alia, that as the proceeding was interlocutory, by virtue of the proviso to the then O 38 r 3 of the SCR, which provided that on interlocutory proceedings, an affidavit might contain statements of information and belief, with the sources and grounds thereof. Barnard J refused the application on grounds that he could put irrelevant matters out of his mind. However, it was allowed upon appeal, and the affidavits were struck out. In the course of the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Hobson LJ held that for the purpose of O 38, the proceeding was not an interlocutory proceeding, where an issue had to be determined. Thus, the affidavit of the husband, which contained materials, much of which was irrelevant and pure hearsay, which the court could not take into account in the form in which it stood. In dealing with O 38 r 3, the court referred to the case of Gilbert v. Endean [1878] 9 Ch D 259, which draws a distinction between interlocutory proceedings generally and interlocutory proceedings where an issue has to be determined, as in this case, it is to suspend the mother's right of access to the child of marriage. The father's application to suspend the right of access of the mother to the child of the marriage was held by the Court of Appeal as not an interlocutory proceeding (although interlocutory in form) as it was an application to decide on the rights of parties.

[40] The proviso of the English RSC O 38 r 3 is in pari materia with our O 41 r 5(2) of the ROC 2012.

[41] Coming back to the matter before us, Judicial Review application is unlike the usual Civil Suit where in the former there is an application for leave before the applicant can proceed to the substantive hearing of the Judicial Review application. In an application for leave for Judicial Review application, in the event there is a dismissal of the leave application, the applicant's rights would be determined to its finality. There will be no more hearing of the substantive Judicial Review application. Although the application for leave in a Judicial Review proceedings is the initial step in the motion towards the hearing of the substantive Judicial Review application, it is not an interlocutory proceeding/ application as the rights of the applicant may be determined at the leave stage, as in the present appeal.

[42] The Singapore Court of Appeal's decision in OpenNet Pte Ltd v. Info Communications Development Authority of Singapore [2013] 2 SLR 880 is the first Court of Appeal Singapore's pronouncement on this subject and interprets the phrase "interlocutory application" in the fifth Schedule para (e)(iv) Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1969 (SCJA). The issue before the Court of Appeal then was, whether the appellant therein required leave to appeal against an order made by the High Court Judge refusing leave to the appellant to commence Judicial Review proceedings. It was argued by the respondent, inter alia, that the appellant required leave to appeal because the application for leave to commence judicial review was an "interlocutory application" under sub-paragraph (e) of the Fifth Schedule of the SCJA. The respondent further argued that, an application for leave was "interlocutory" in nature because it was "simply a preliminary step to the substantive application for judicial review"; it may be made by ex-parte originating summons without the respondent being heard; and the appellant had itself proceeded on the basis that the application was "interlocutory" in nature because its affidavits in support of the application for leave stated that they contained statements of information or belief, which were admissible under O 41 r 5 of the Rules of Court for "interlocutory proceedings". The Court of Appeal held that as the refusal of leave meant that the substantive rights of the parties had been determined and had an absolute end, thus, the application for leave to commence judicial review here was not an "interlocutory application" under sub-paragraph (e) of the Fifth Schedule of the SJCA. Accordingly, no leave to appeal was required before the appellant filed an appeal against the decision of the High Court refusing leave to commence judicial review proceedings.

[43] OpenNet Pte Ltd v. Info Communications Development Authority Of Singapore was however, decided before the amendment to the SCJA, which took effect on 1 January 2019. Under the current legislative framework, leave of court is required to adduce further evidence in all appeals (including interlocutory matters), in respect of matters occurring before the date of the decision from which the appeal was sought. In this regard, s 59(4) of the Supreme Court of Judicature Act (Cap 322, 2007 Rev Ed) (SCJA) states that:

"Except as provided in subsection (5), such further evidence may be given to the Court of Appeal only with the permission of the Court of Appeal and on special grounds."

Section 59(5) of the SCJA states that:

"Such further evidence may be given to the Court of Appeal without permission if the evidence relates to matters occurring after the date of the decision appealed against."

Recent changes have also been made to the detailed appellate processes now enshrined in the new Singaporean Rules of Court ("Singaporean ROC 2021") to achieve cost-effectiveness and the efficient use of court resources. Presently, O 18 r 8(6) of the Singaporean ROC 2021 provides that:

"Subject to any written law, the appellate Court has power to receive further evidence, either by oral examination in court, by affidavit, by deposition taken before an examiner, or in any other manner as the appellate Court may allow, but no such further evidence (other than evidence relating to matters occurring after the date of the decision appealed against) may be given except on special grounds."

[Emphasis added]

[44] This differs from the position under s 69(3) of our CJA, where the twin requirements of leave of court and special grounds are imposed in respect of further evidence for appeals from a judgment, trial or hearing on the merits. As has been noted above, in Malaysia, further evidence may be given without leave of court in interlocutory applications at the Court of Appeal (see: s 69(2) of our CJA and r 7(2) of the RCA 1994).

[45] Similarly, the learned High Court Judge had distinguished (at para [36] in His Lordship's judgment) on the role of the affidavits in support of the application for leave in the Judicial Review application and the substantive application for Judicial Review:

"[36] In judicial review applications, as opposed to other interlocutory applications, the distinguishing factor is that the affidavit verifying facts is the same affidavit used for the substantive application. Thus according to Tuan Sarip Hamid, while the leave application for review is interlocutory in character, the affidavit may require direct knowledge depending on the nature of the subject matter...."

[46] In this regard the minority decision in the Court of Appeal is not far off from what we have elucidated on the issue of the application for leave in the present appeal, namely, that, the application for leave in the Judicial Review proceedings is not an interlocutory proceeding for the purpose of r 7(2) of the RCA 1994, and hence leave is required. Therefore, although the application for leave for Judicial Review is interlocutory in form, it is an application to decide on the rights of the parties, hence as regards evidence it ought not be regarded as an interlocutory proceeding within the meaning of O 41 r 5(2) ROC 2012 (see Gilbert v. Endean, Rossage v. Rossage, Tuan Hj Sarip Hamid).

[47] It should also be noted that r 7(2) RCA 1994 states that the fresh evidence "may be given without leave". We think it is significant that in r 7(2) RCA 1994, the word "may" has been used. This suggests that the court retains a discretion to allow for such evidence to be adduced, but this does not mean the court must invariably allow for such evidence to be adduced without leave, without some kind of filtering mechanism.

[48] In our opinion, such a filtering mechanism is important as a means of preventing the appellate courts from being flooded with frivolous applications to adduce fresh evidence, thus taking up precious judicial time. If such applications were not subject to some measure of judicial control, it would upend finality in litigation, which is a pillar of our system of justice. Of course, in considering applications under r 7(2) RCA 1994, the court also balances the interests of justice depending on the particular circumstances of the appeal before it. As such, it is our opinion that the presence of the word "may" means that the appellate court may, in a fit and proper case, decide against allowing evidence which falls under r 7(2) RCA 1994 from being adduced.

[49] In the instant case, the Additional Evidence Application No.1 via encl 26 sought to adduce Mohamad Nizar's 1st Affidavit dated 2 December 2024 and the Addendum Order, dated 29 January 2024. This means that Mohamad Nizar's 1st Affidavit was after the decision of the High Court, which was on 3 July 2024, whereas the Addendum Order was in existence even before the application for leave to commence for Judicial Review which was on 1 April 2024.

[50] As such, Mohamad Nizar's 1st Affidavit falls under matters which occurred subsequent to the date of the decision appealed against, while the Addendum Order existed before the decision of the High Court. Thus, Mohamad Nizar's 1st Affidavit may be adduced without leave of court, but leave of court is required to adduce the Addendum Order.

The Introduction Of New Evidence At The Appellate Level In Malaysia And Other Jurisdictions

[51] Rule 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 was introduced in 1998 through PU(A) 380/1998. Prior to the introduction of r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994, the Courts applied the Ladd v. Marshall principle of admitting fresh and additional evidence at the appellate level, where the applicant must show:

(i) the evidence could not have been obtained with reasonable diligence for use at the trial;

(ii) the evidence must be such that, if given, it would probably have an important influence on the result of the case, although it need not be decisive; and

(iii) the evidence must be such as is presumably to be believed, or in other words, it must be apparently credible, although it need not be incontrovertible.

[52] Pre-Rule 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 saw the decision of Lau Foo Sun v. Government Of Malaysia [1970] 1 MLRA 219, which applied the Ladd v. Marshall principle of admitting fresh evidence at the appellate level. The application for the admission of fresh evidence was dismissed as the appellant had not shown that the evidence which was sought to be adduced could not have been obtained with reasonable diligence for use at the trial.

[53] Subsequent case of Chai Yen v. Bank Of America National Trust & Savings Association [1980] 1 MLRA 578, where the application was dismissed as the applicant could not have satisfied the first requirement of Ladd v. Marshall, namely the evidence could not have been obtained with reasonable diligence for use at the trial. Failure to satisfy the first requirement was sufficient for the dismissal of the application. Further, the Court held that the evidence sought to be adduced, namely the guarantee, was of no relevance to the application.

[54] As for post r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994, the Federal Court in V Medical Services M Sdn Bhd v. Swissray Asia Healthcare Sdn Bhd [2025] 3 MLRA 360 has the occasion to deal with r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994. The Appellant, V Medical Services (M) Sdn Bhd ('the Company'), sought a Fortuna injunction to restrain Swissray from bringing a winding up petition on the grounds that there subsisted a dispute in relation to the debt which comprised the subject matter of the winding up petition.

[55] The primary issue confronting the Federal Court in V Medical Services M Sdn Bhd v. Swissray Asia Healthcare Sdn Bhd was the test to be adopted when a defendant in a winding up petition, disputes the existence of the debt which comprises the basis for the winding up petition, but the dispute relating to such debt falls within the scope of an arbitration agreement.

[56] Just before the first hearing date at the Federal Court, the Company applied to adduce fresh evidence, namely the evidence of Mr Thawichai, Swissray's previous Sales and Marketing Director, who had personally dealt with the Company as Swissray's representative, in relation to all crucial communications with the Company, particularly the settlement negotiations. Mr Thawichai had left Swissray's employment sometime on 31 October 2018, and the Company had only been able to locate and contact him after the hearing in the Court of Appeal.

[57] The Federal Court applied r 7(3A) of the RCA vide r 3 of the Rules of the Federal Court 1995, and opined that r 7(3A) "encapsulates" the test in Ladd v. Marshall. The Federal Court applied the criteria for the fresh evidence to be admitted, namely the fresh evidence:

a) could not have been located or obtained with reasonable diligence prior to the hearing of the appeal;

b) is genuine or authentic and not patently unbelievable or doubtful; and

c) was likely to be of determinative influence in the appeal. (para [78] of the judgment).

The Federal Court allowed for the evidence to be admitted.

[58] This Court in V Medical Services M Sdn Bhd v. Swissray Asia Healthcare Sdn Bhd described r 7(3A) RCA 1994 as an encapsulation of the test in Ladd v. Marshall before proceeding to apply the test to the facts of the case. The minority decision of the Court of Appeal in our present appeal held that r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 codifies the principle of Ladd v. Marshall (see para 51 of the minority decision of the Court of Appeal). Question 1 in our present appeal seeks a determination from this court whether the principles established in Ladd v. Marshall have been codified or merely reflected in r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994, which we will do at the end of this judgment.

[59] In the UK, the Ladd v. Marshall criteria were not expressly codified in any written law, but they serve as useful interpretive common law tools when judges give legal effect to provisions such as the English Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) in r 52.21(2) and Practice Direction (PD) of the 5.11 UK Supreme Court Rules 2024.

[60] On the issue of reasonable diligence, from our examination of the cases in the UK, if the said fresh evidence could have been obtained at or before trial, it is unlikely to be admitted on appeal (see the Court of Appeal England & Wales judgment in Hertfordshire Investments Ltd v. Bubb And Another [2000] 1 WLR 2318). The court assesses whether the party had taken reasonable steps to obtain the evidence, whether the evidence was discoverable with reasonable efforts or within the party's control. In light of the finality of proceedings, fresh evidence should not be used as a litigation tactic, allowing parties to wait for the outcome of the trial and, if unsuccessful, introduce new evidence on appeal (see Al-Sadeq v. Dechert LLP [2024] EWCA Civ 28). The appellate court must also meticulously scrutinise the case timeline to determine if reasonable diligence was exercised in obtaining the evidence. (Al-Koronky v. Time Life Entertainment Group [2006] EWCA Civ 1123).

[61] On the issue of "Important influence", English case law suggests that courts will not admit fresh evidence on appeal unless its admission brings a material change to the trial's outcome. (See: Al-Koronky (supra); Singh v. Habib [2011] EWCA Civ 599; R (On The App. Of Yasser-Al Siri) v. Secretary Of State For The Home Department [2021] EWCA Civ 113). Fresh evidence will only be admitted in exceptional situations:

(i) when the integrity of the trial has been compromised (Hamilton v. Al-Fayed (No 2) [2001] E.M.L.R 15); or

(ii) the trial has been tainted with fraud / conspiracy / bad faith (mala fide) (Singh v. Habib [2011] EWCA Civ 599).

[62] Depending on the context, English courts are generally more lenient in admitting fresh evidence in child care proceedings (Re EChildren: Reopening Finding Of Fact [2020] 2 All ER 539), but prioritise the finality of proceedings in Judicial Review cases (see R (On The App. Of Yasser-Al Siri (supra)).

[63] The credibility criterion in Ladd v. Marshall is assessed on a case-by-case basis if it is relevant to the issue on appeal. This is the approach consistently taken by the English authorities:

• Hertfordshire Investments Ltd: The Court of Appeal disposed the appeal by considering only the reasonable diligence criterion in Ladd v. Marshall;

• Hamilton v. Fayed (No 2): The Court of Appeal based its reasoning on the credibility criterion when it was alleged that the integrity of trial was compromised (i.e.: there was new evidence to challenge the credibility of trial witness). Similar to the UK Supreme Court approach in Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council v. Secretary Of State For Communities And Local Government [2011] 2 AC 304 where the appeal was disposed of based on the credibility criterion in Ladd v. Marshall); and

• Terluk v. Berezovsky [2011] EWCA Civ 1534 and Al-Sadeq v. Dechert LLP [2024] EWCA Civ 28: The credibility criterion was assessed together with the reasonable diligence criterion in Ladd v. Marshall.

[64] Credibility is a question of fact for the appellate court to assess when deciding whether to admit fresh evidence. Courts are entitled to assess the credibility of the fresh evidence against other forms of corroborating evidence at trial, such as oral testimonies by witnesses and other forms of documentary evidence. This was the approach taken in the case of Terluk, Al-Sadeq v. Dechert LLP and Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council.

[65] If the said fresh evidence could have and should have been obtained at trial, its credibility may be called into question if it is subsequently adduced on appeal. This is because the submission of fresh evidence should not be used as a litigation tactic and the opposing party should be given sufficient time to verify its accuracy, credibility and reliability during trial preparation. (See: Al- Koronky v. Time Life Entertainment Group (supra) and Terluk v. Berezovsky)

[66] In Singapore, the extent to which the principles in Ladd v. Marshall are applied in an appeal depends on the nature of the proceedings in question. Even after considering the nature of the proceedings below, the court retains an overarching discretion to act as the interests of justice require. Thus, the conditions in Ladd v. Marshall may be relaxed or applied more strictly in accordance with the circumstances of a particular matter before the court, to reach a just and common-sense outcome.

[67] In Australia, while some of the Australian courts do not expressly refer to Ladd v. Marshall, the essence of the test they apply remains the same.

The Differences Between The Elements In Ladd v. Marshall And Rule 7(3A) Of The Rca 1994

[68] This aspect is relevant to answer Questions 1, 2, 3 and 7 posed.

Availability / Reasonable Diligence

[69] The first condition in Ladd v. Marshall is that the fresh evidence may be admitted if the applicant can satisfy the court that it could not have been obtained with reasonable diligence for use at trial.

[70] Whereas under r 7(3A)(a) RCA 1994, the court must be satisfied that at the hearing before the High Court or the subordinate court, as the case may be, the new evidence was not available to the party seeking to use it, or that reasonable diligence would not have made it so available.

[71] It appears that the r 7(3A) RCA 1994 provide for 2 situations under para (a), which we consider as a lower threshold than the requirement in Ladd v. Marshall, which only specifies one condition under the 1st element for the new evidence to be accepted. The Rule requires the applicant to satisfy either one of the conditions in (a), namely, (i) the new evidence was not available to the party seeking to use it; or (ii) that reasonable diligence would not have made it so available. It is clearly a disjunctive requirement.

"Important Influence" v. "Determining Influence"

[72] In the present proceedings, the appellant submits that there are "significant differences" between the Ladd v. Marshall criteria and those set out in r 7 of the RCA 1994, and that the phrase "determining influence" in r 7(3A) imposes a higher/stricter threshold compared to the "important influence" requirement in Ladd v. Marshall. The appellant submits that there is "uncertainty" in the application of r 7(3A) concerning the admission of fresh evidence at the appellate stage because the Court of Appeal had applied the rule "inconsistently".

[73] The respondent's reply is that the application of Ladd v. Marshall does not render r 7(3A) superfluous as the conditions therein are to be read harmoniously with r 7(3A) RCA. On the appellant's submission that r 7(3A) imposes a stricter threshold, the respondent's answer is that Ladd v. Marshall actually places a higher threshold on the party seeking to adduce the fresh evidence, as r 7(3A) only requires two conditions to be fulfilled, whereas Ladd v. Marshall lays down three conditions. The respondent also submits that, despite the difference in words used, "important influence" and "determining influence" have been used interchangeably.

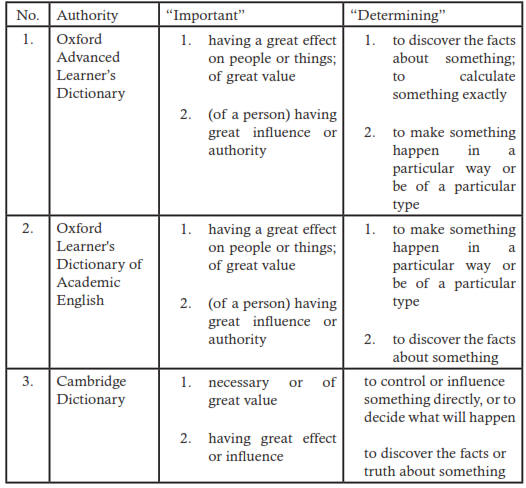

[74] It is pertinent at this juncture to refer to the dictionary definition of "important" and "determining":

[75] From the aforesaid, evidently, the literal/dictionary meaning for both is different.

[76] Prima facie, one may accordingly argue that "determining influence" sets a higher standard than that required by "important influence", because while all evidence which has a "determining influence" will necessarily be important, arguably not all evidence that has an "important influence" will necessarily be determinative. In other words, important evidence may and will usually also be determinative evidence, but the fact that it is of great value may or may not be the deciding factor in the matter.

[77] This is especially true at the trial stage when the court has to consider a myriad of evidence before arriving at a decision. However, at the appellate level when the "determining influence" test in r 7(3A) RCA 1994 comes into play, we prefer the view that, notwithstanding the different semantics, "important influence" is comparable to "determining influence" because at that level, the only evidence in question is that particular piece of evidence sought to be adduced and whatever the label applied, the effect will necessarily be determinative of the outcome on the case at the lower court.

[78] To illustrate our proposition, assuming that instead of "determining influence", the appellate court uses "important influence" to decide if new evidence should be adduced: if the evidence were held to be not important, it would not be allowed, and the status quo remains — hence also determinative for the appellate level and below. In this context, the evidence is important in that it is determinative. It must be borne in mind that the appellate court, when evaluating an application to adduce further evidence under r 7(3A) RCA 1994, is already in a position where it is in possession of the other relevant material facts which led to the decision given by the lower court. It thus follows that regardless of the label ascribed to the evidence, be it "important" or "determining", what is crucial is whether the evidence has a likelihood of affecting the outcome of the decision of the court below.

[79] Fortifying our view is the fact that under r 7(3A)(b) RCA 1994, all that is required is that the evidence "would have had or would have been likely to have had a determining influence upon the decision of the High Court or the subordinate court". Clearly, "would have been likely to have" is not "would have had". "Would be likely to have" suggests that it is sufficient for the evidence to be important enough to probably alter the outcome of the decision of the lower court. In light of this, it is our opinion that the decided cases were not wrong in applying the "important influence" criterion despite the terminology employed in r 7(3A) RCA 1994.

[80] For these reasons, while it is true that taken at face value, the dictionary meaning for "determining influence" suggests a higher threshold, we are of the view that, practically speaking, and in reality, the demarcation between "important" and "determining" under r 7(3A) is of no consequence at the appellate level.

Credibility

[81] The third condition inLadd v. Marshall stipulates that the evidence "if given", must be such as is presumably to be believed, or in other words, it must be apparently credible, although it need not be incontrovertible. Rule 7(3A) does not expressly mention "credible" or "credibility", but it refers to evidence which "if true" would have or would be likely to have a determinative influence.

[82] It is our considered view that the existence of the words "if true" and the absence of the words "credible" or "credibility" does not affect the application of the third condition in Ladd v. Marshall.

[83] A closer examination reveals that the judicial process undertaken in both Ladd v. Marshall and r 7(3A)(b) RCA 1994 remains effectively the same in substance and purpose, and this is for the following reasons. Both the words "if true" and "if given" require the court to hypothetically assess the impact of the fresh evidence would have had on the earlier decision. The word "if true" under r 7(3A)(b) directs the court to assess the likely influence of the new evidence on the outcome, assuming it is truthful. The word "if given" in Ladd v. Marshall requires the court to consider what influence the evidence would have had if it had been presented at trial.

[84] In both instances, the court does not make a final finding of truth at this stage but rather assumes the truth (or credibility) of the evidence to determine its potential effect on the earlier decision.

[85] Furthermore, in Ladd v. Marshall, one of the criteria is that the evidence must be "apparently credible although not incontrovertible". This mirrors the"if true" requirement in r 7(3A)(b), which similarly does not demand proof of veracity but assumes truth for the sake of assessing influence.

[86] Therefore, despite using the word "true," r 7(3A) is not imposing a different threshold of proof; rather, it invites the court to proceed on the assumption that the evidence is true for evaluative purposes, just as the court in Ladd v. Marshall considers the hypothetical effect of the evidence if it had been admitted.

[87] We conclude that, in the UK, while the phrase "special grounds" is absent from the Civil Procedure Rules, the established principles remain relevant as examples of how the courts strike a fair balance between finality in litigation and the desirability that the judicial process should achieve the right result (see Hertfordshire Investments Ltd at p 2325E). Be that as it may, it is significant to note that English authorities have held that the Ladd v. Marshall criteria are "principles rather than rules" which should not be seen as a "straightjacket" confining the exercise of the court's discretion in deciding whether to permit the introduction of new evidence (see Hertfordshire Investments Ltd at 2325H. Also seeHamilton v. Al-Fayed (No 2) [2001] E.M.L.R. 15 at 401).

[88] In Singapore, the Court of Appeal made a similar pronouncement to that effect in Anan Group (Singapore) Pte Ltd v. VTB Bank (Public Joint Stock Co) [2019] SGCA 41, where the Court of Appeal said that:

"[37] The above analysis, which focuses on the nature of the proceedings giving rise to the judgment appealed against, is only one facet of the inquiry which the court must undertake in determining the rigour with which the Ladd v. Marshall principles should be applied. The cases reveal that even after the nature of the proceedings below have been considered, the fulfilment of the Ladd v. Marshall conditions does not bind the court's hands in admitting fresh evidence, and conversely the court is not prevented from admitting fresh evidence even in the absence of strict compliance with these conditions.Rather, the court retains its overarching discretion to act as the interests of justice require, which includes the discretion to admit new evidence despite the applicant's failure to satisfy the conditions of Ladd v. Marshall. Thus, this court has rightly cautioned that the Ladd v. Marshall test should not be applied rigidly as if it were a statutory provision..."

[Emphasis added]

[89] The Australian authorities have acknowledged that:

"There is no precise formula as to how the Court should exercise its discretion in deciding whether to admit further evidence on appeal. However, it has been said that the exercise should be undertaken with regard to the context in which it arises (including the nature of the litigation) and also the public interest in the finality of litigation: Doherty v. Liverpool Hospital [1991] 22 NSWLR 284 at 297" (see: the Supreme Court of Western Australia case of Australian Democrats WA Division Inc And Anor v. Australian Democrats VIC Division Inc & Ors [BC 9805206] (supra) at 7)

[90]It is therefore clear that the courts in the UK, Singapore and Australia generally apply the Ladd v. Marshall principles in accordance with their respective legislative regimes but do not regard the conditions as a set of inflexible rules to be applied uncritically. Nevertheless, in the UK, they remain powerful and persuasive in interpreting the English CPR r 52 and PD 5.11 of the UKSC Rules 2024, with the overriding concern that it should be applied with considerable care (see Hertfordshire Investments Ltd v. Bubb And Anor). The courts in these jurisdictions have on occasion, departed from demanding full compliance with a particular condition when the interests of justice require it. In Singh v. Habib, the Court of Appeal considered the Ladd v. Marshall criteria and held that there was a stronger public interest justification for admitting fresh evidence, in particular, when there was an allegation of fraud and conspiracy to fabricate a claim. However, public policy consideration is not part of the Ladd v. Marshall criteria.

[91] Given the foregoing, it is our judgment that a similar approach may be adopted by the courts here: namely that while the Ladd v. Marshall conditions remain apposite, they should not be construed as strictly as though they have statutory or legislative force, but rather, they should be treated as a set of guidelines to be adapted as the interests of justice may require according to the circumstances of a particular matter, in accordance with our legislative regimes i.e. r 7 of the RCA 1994. We are of the considered view that the Ladd v. Marshall criteria serve as a useful interpretive tool when Judges give legal effect to the provisions of the said Rule.

The Application Of Rule 7(3A) RCA 1994 To The Present Appeal

[92] We will now focus on the facts of the present appeal, whether the respondent has satisfied the requirements of r 7 of the COA Rules to admit the new evidence.

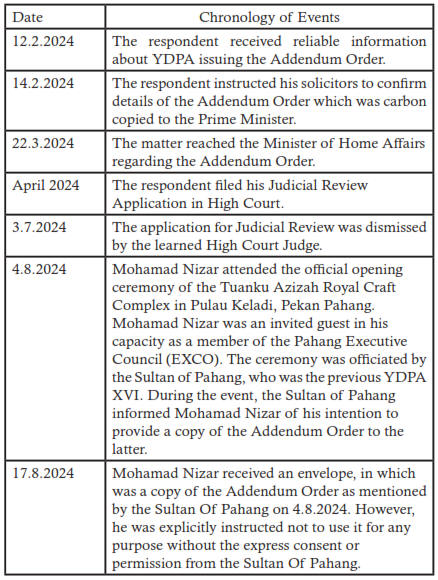

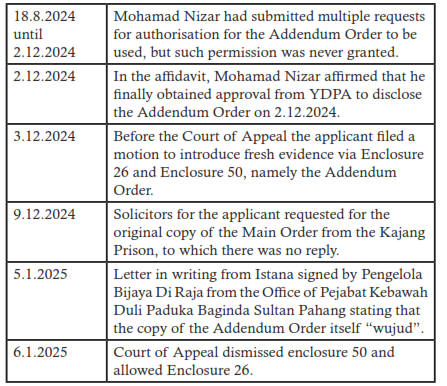

[93] First, on the requirement by the provision of r 7(3A)(a) of the RCA 1994, that "the new evidence was not available" or that "reasonable diligence would not have made it so available". To determine this issue, we refer to the chronology of events as to the availability of the new evidence, vis-à-vis, the Addendum Order and the efforts to obtain the same, which are as follows:

[94] From the chronology of events as aforesaid, as early as 12 February 2024, numerous efforts were taken by the respondent to obtain information to confirm the details of the Addendum Order through his solicitors. This is understandable, given that he is in prison serving his sentence. He has no choice but to rely on the good office of his solicitors. From 12 February 2024 until the time the respondent filed the Judicial Review application in April 2024, his efforts to obtain the confirmation on the Addendum Order via the Prime Minister's Office, the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Pardons Board, the DG of Legal Affairs of the PM's Department, all met with a dead end, if not futile. This continued until the High Court delivered its decision on 3 July 2024.

[95] Efforts to obtain the Addendum Order were continued after the decision of the High Court, by the respondent's son, Mohamad Nizar, who received a call from the Pengelola Bijaya Diraja Kebawah Duli Paduka Baginda Sultan Pahang, Dato' Haji Ahmad Khirrizal Ab Rahman from the Pahang Palace "dengan cara tiba-tiba" on the night of 4 January 2025 at 10.25 pm., when he was informed that a letter would be sent to him personally, later. The letter was sent to Mohamad Nizar on 5 January 2025, by which he then affirmed an affidavit. In his affidavit in encl 52, he said that:

"8. ...beliau (Pengelola Bijaya Diraja Kebawah Duli Paduka Baginda Sultan Pahang, Dato' Haji Ahmad Khirrizal Ab Rahman from the Pahang Palace) menyerahkan kepada saya sepucuk surat bertarikh 4 Januari 2025.

9. Surat tersebut menyatakan bahawa KDPB Sultan Pahang selaku Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong XVI telah pada 29 Januari 2024 menitahkan (melalui Titah Addendum) supaya perayu dalam rayuan ini menjalani baki hukuman pemenjaraan menerusi penahanan dalam rumah (house arrest). Seterusnya KDPB Sultan Pahang juga telah memperakukan bahawa Titah Addendum berkenaan memangnya wujud dan sahih. Saya memang percaya penuh bahawa KDPB Sultan Pahang telah pun mengambil keputusan menghantar surat tersebut memandangkan perkembangan terkini dalam beberapa hari ini bagi hemat saya berniat untuk memberi pengesahan terhadap fakta-fakta yang sebenarnya. Saya bersyukur bahawa Baginda Berkenan dan bertitah untuk mengesahkan Titah Adendum itu memang wujud melalui surat rasmi pejabat KDPB Sultan Pahang pada 5 Januari 2025.

10. Dalam surat tersebut, KDPB Sultan Pahang secara jelas mengesahkan bahawa addendum yang saya lampirkan dalam affidavit saya bertarikh 2hb Disember adalah addendum bertarikh 29 Januari 2024 yang sah dan benar, yang memerintahkan bahawa Dato'Sri Najib bin Tun Haji Abd Razak perlu menjalani baki hukuman penjaranya di bawah tahanan rumah."

[96] Prior to 2 December 2024, there was no authorisation for Mohamad Nizar to disclose the Addendum Order. It was only on 5 January 2025 that Mohamad Nizar received the letter from Pengelola Bijaya Diraja from the Office of Pejabat Kebawah Duli Paduka Baginda Sultan Pahang, which states that the Addendum Order exists.

[97] Clearly from the above, the 1st condition of r 7(3A)(a), namely, that the new evidence was not available to the respondent, has been fulfilled. Apart from the relentless and repeated attempts to obtain the Addendum Order by the respondent, there is also the issue of the sensitive nature of the Addendum Order and the strict protocol of matters involving the Palace. Hence, we are of the view that the respondent has also satisfied the 2nd condition of r 7(3A)(a) of the RCA 1994 on "reasonable diligence". The minority in the Court of Appeal had erred in fact in this respect when Her Lordship ruled that the reasonable diligence element was not fulfilled. (Paras 56-64 of the Court of Appeal Minority judgment).

[98] In relation to the requirement of "determining influence" under r 7(3A) (b), the issue is whether the Addendum Order would have a determining influence on the High Court decision. The minority decision in the Court of Appeal at para [55] of the judgment opined that the respondent had satisfied the conditions (ii) and (iii) of Ladd v. Marshall and ruled that "the proposed fresh evidence will have an important influence on the result of the appeal and that the fresh evidence is credible".

[99] The issue of "determining influence" is important in light of the argument made by the appellant in their written submissions that the "subject matter herein hinges on the "high prerogative exercisable" by the YDPA. As such, the court has no jurisdiction to confirm or vary the decision made by the YDPA in the pardon process", by placing reliance on the case of Public Prosecutor v. Soon Seng Sia Heng & 9 Other Cases [1979] 1 MLRA 384. The case of Juraimi Husin v. Pardons Board Of State Of Pahang & Ors [2002] 2 MLRA 121 which involved a petition for clemency, the Federal Court held that the decision-making process of the decision by the Sultan of Pahang under art 15 of the Laws of the Constitution of Pahang, read together with art 42 of the Federal Constitution, is not justiciable.

[100] There are 2 points to take note of, from the arguments by the appellant, namely:

(i) the issue on the element of "determining influence" of the new evidence; and

(ii) whether it (the new evidence) affects the "high prerogative exercisable" by the YDPA (issue of non-justiciability).

[101] For this, we refer to the essential excerpt of the Addendum Order, which is as follows:

"... Beta dengan ini menitahkansebagai tambahan kepada keputusan Beta berhubung ..., Dato' Sri Mohd Najib bin Tun Haji Abdul Razak...pada Mesyuarat Lembaga Pengampunan Wilayah-Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur, Labuan dan Putrajaya kali ke 61 pada hari Isnin, 29 Januari 2024... Dato' Sri Mohd Najib bin Tun Haji Abdul Razak...menjalani baki hukuman menerusi penahanan dalam rumah (House Arrest)..."

[102] To answer the issue on the element of "determining influence" of the new evidence as mentioned at para [100] (i) above, with these essential excerpts at para [101] as aforesaid which is before this Court, at this juncture, this Court cannot conclusively dismiss the Addendum Order as not forming part of the Pardons Order of the Pardons Board and neither can we say that it is. The Addendum Order originated from the Palace of the Sultan of Pahang, who was the YDPA XVI on 29 January 2024. True or not of the Addendum Order and its validity cannot be determined conclusively at this stage.

[103] However, it is our view that, following the precise words in r 7(3A)(b) of the RCA 1994, the Addendum Order, "if true, would have had or would have been likely to have had a determining influence upon the decision of the High Court" in the Judicial Review application. In other words, this issue as to whether the Addendum Order is "true" or not, is an arguable point to be ventilated in the substantive hearing of the Judicial Review application.

[104] Given the aforesaid, it is our judgment that the respondent has satisfied the elements under r 7(3A) RCA to admit the Addendum Order as new evidence to be used at the substantive hearing of the Judicial Review application, which is an indication that leave ought to be granted.

[105] On the point as stated in para 100(ii) above-mentioned, on the issue of justiciability, it is trite that the prerogative mercy of the YDPA is non- justiciable and the Courts cannot confirm or vary it; in other words, the Courts have no jurisdiction to do so. However, the facts in the present appeal are rather peculiar. There is the Pardons Order of the Pardons Board dated 29 January 2024 and the Addendum Order, which "appears" to be "tambahan kepada keputusan Beta..", to the Pardons Order also dated 29 January 2024.

[106] In this regard, we are not attempting to vary nor confirm the Order of the YDPA XVI/Pardons Board dated 29 January 2024. But as of now, the Addendum Order exists and its status vis-à-vis its validity or whether it is true needs to be ascertained at the substantive hearing, which we do not consider it right or fair for us to express any view on this point at this stage. It is a point for further investigation on a full inter partes basis with all such evidence as is necessary on the facts and all such arguments as are necessary on the law.

[107] Therefore, in answering Questions 1-3, it is our considered view that r 7(3A) RCA 1994 is the statutory provision with regard to admission of new evidence at the appellate level. Although the exact wording of the essential elements in Ladd v. Marshall and the elements in r 7(3A) RCA 1994 are not word-for-word the same, the effect and the consequence of applying the elements in r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994 and the elements in Ladd v. Marshall lead to the same conclusion. As to whether r 7(3A) "encapsulates", "codifies" or "reflects" the test in Ladd v. Marshall, for want of a better term, we prefer the word "encapsulates" which means it expresses the essential features of the test in Ladd v. Marshall succinctly.

[108] To sum up, we allow the Addendum Order to be admitted as new evidence under r 7 of the RCA 1994, and leave is granted to the respondent for the Judicial Review application in the High Court. Therefore, we answer the Questions as follows:

• For Question 1: The principles established in Ladd v. Marshall is encapsulated in r 7(3A) of the RCA 1994.

• For Questions 2 and 3: negative

• Questions 4-6 are no longer relevant in view of the concession by the learned AG of the existence of the Addendum. They are now hypothetical and academic which we decline to answer.