Federal Court, Putrajaya

Hasnah Mohamed Hashim CJM, Nallini Pathmanathan, Rhodzariah Bujang FCJJ

[Civil Appeal No: 02(f)-16-05-2024(J)]

7 July 2025

Public Utilities: Electricity — Disconnection of — Wrongful disconnection — Damages, assessment and grant of — Special damages and exemplary damages — Appeal against Court of Appeal's reversal of High Court's award of damages for wrongful disconnection of electricity by respondent despite clear finding of liability against the respondent — Whether requirement that special damages be 'strictly proved' imposed a standard higher than balance of probabilities — Whether claim for special damages not demonstrated or verified — Whether exemplary damages could be awarded against a statutory body such as respondent — Principles applicable — Quantum to be awarded

This was an appeal by Big Man Management Sdn Bhd ("the appellant") against the Court of Appeal's reversal of the High Court's award of damages to the appellant for wrongful disconnection of electricity by Tenaga Nasional Berhad ("the respondent"), despite a clear finding of liability against the respondent. The respondent had, on two occasions, disconnected the electricity supply to the premises of an ice-making factory owned by Ice Man Sdn Bhd, which was operated by the appellant under contract, with electricity accounts held in the appellant's name. The two heads of damages that arose for consideration in this appeal were special and exemplary damages. The basis for the Court of Appeal's decision, in essence, was that the appellant's claim for special damages was not demonstrated or verified. With respect to exemplary damages, the issue was whether such damages could be awarded against a statutory body such as the respondent, which held a monopoly over the electricity supply. The appellant was granted leave to appeal on the following questions of law: (1) whether the evidential approach of the Court of Appeal with reference to the expression "special damages must be specifically pleaded and strictly proven" stood to be corrected and/or clarified so that special damages only needed to be established on a balance of probabilities before a trial court; (2) whether exemplary damages were claimable by a consumer of electricity in a breach of contract claim against the respondent, particularly in a case where the respondent, being a statutory body, had consciously and deliberately acted in excess of the powers granted to it under statute, and in light of the fact that it was open for the respondent to claim for this head of damages as established in Tenaga Nasional Bhd (TNB) v. Evergrowth Aquaculture Sdn Bhd & Other Appeals ("Evergrowth"); (3) whether exemplary damages contemplated under the first category of Rookes v. Barnard (ie oppressive or arbitrary conduct) could be extended to claims made against statutory corporations following the development of the law in Kuddus v. Constable Of Leicestershire Constabulary in extending the first category in Rookes v. Barnard to also private corporations and/ or individuals; (4) where a plaintiff had succeeded in establishing liability but failed to prove special damages, whether it was incumbent on a court to award general and/or nominal damages; and (5) where a plaintiff had succeeded in establishing liability but failed to prove damages, whether it was open to a court to order substantial costs against the successful party, having regard to the principles in O 59 rr 2, 3 and 5(2) of the Rules of Court 2012.

Held (allowing the appellant's appeal):

(1) The exercise of determining the measure of damages due to a claimant was neither a robotic mechanical exercise, nor an arbitrary quantum picked out capriciously, nor a measure determined by a Judge's intuition or instinct as to what the Judge thought it ought to be. Most importantly, it was necessary to closely examine and evaluate the documentary and oral evidence before deciding to exclude it in its entirety. Evidence on record ought not to be rejected outright nor ignored where, as in this case, it was sufficient to establish a basis for the claim. An appellate court ought to be slow to reverse a finding of fact which was premised on such a chain of evidence, unless it was patently clear that the documents were a sham or fictitious. In these circumstances, the appellant had discharged its evidentiary burden of proof in relation to its claim for special damages on a balance of probabilities. (paras 29-31)

(2) This Court reversed the Court of Appeal's finding that the appellant failed to prove special damages. The Court of Appeal erred in rejecting the documentary evidence outright. Hence, the High Court's award for special damages for the first and the second disconnections was reinstated with interest. As for the relevant question of law, ie Question 1, it was trite that special damages in a civil claim only needed to be established on a balance of probabilities. The phrase "strictly proved" did not denote that evidence was bound to be adduced to a greater degree than the balance of probabilities. This meant that the term 'strictly proved' in relation to the evidentiary burden did not increase such burden in any manner otherwise than to require that it met the civil standard of proof. As Questions 4 and 5 were premised on the basis that the appellant failed to prove special damages, it was not necessary to answer the same. (paras 43-45)

(3) It was not in dispute that the respondent had wrongfully disconnected the electricity supply to the premises of the appellant in order to force it to settle its outstanding bills. Both the courts below were unanimous that the respondent was liable for such wrongful disconnection of electricity. However, the question that arose for consideration was whether there was a factual basis warranting an expansion of the law to allow for the grant of punitive damages or exemplary damages when such an extension was not warranted. The respondent had a statutory duty to provide electricity to the appellant according to s 24 of the Electricity Supply Act 1990 ("ESA"). The duty was subject to exceptions under s 25 of the ESA, none of which were present in this case. It thus followed that the respondent's unlawful disconnection caused considerable damage to the appellant. However, it was argued by the respondent that the appellant did not plead any tortious cause of action in this context, nor a breach of statutory duty. Therefore, the respondent maintained a claim for damages, particularly exemplary damages, had no proper foundation in the recognised categories of law allowing for such grant. (paras 78, 80 & 81)

(4) On the facts, the appellant's Statement of Claim disclosed a valid cause of action premised on a breach of a statutory duty, namely the duty to provide electricity to consumers. That duty was breached when that supply was unlawfully disconnected by the respondent. As a cause of action based on statutory breach subsisted, a claim for exemplary damages in contract was not the only option available to the appellant. If the only cause of action available were solely in contract, without any other actionable wrong, it would be difficult to even consider an award of exemplary damages. However, since a cause of action premised on a breach of statutory duty was available from the pleadings, the Court could consider the possibility of awarding exemplary damages. (paras 91-93)

(5) The evidential basis for an award of exemplary damages must necessarily arise from a consideration of the factual matrix of the case. The grounds of judgment of the High Court comprised the proper mode of assessing whether there was any evidential basis for such a claim because the court of first instance enjoyed the audio-visual advantage and was best positioned to assess the factual matrix of this matter. Hence, serious consideration was given to the findings of the High Court. The trial Judge had stated that the respondent conducted itself in a manner which was gravely improper and excessive, in disconnecting the appellant's electricity supply. (paras 94-95)

(6) On whether such conduct warranted the grant of exemplary damages, the following salient factors were considered: (a) the position of the respondent as the sole supplier of electricity in Malaysia put it in a position superior to that of the consumer, the appellant, which afforded the respondent the capacity to abuse its position; (b) as submitted by the appellant, this was "a statutorily regulated relationship arising from the statutorily accorded monopolistic right" to the respondent, the sole licensee for the supply of electricity; (c) it was not in dispute that the respondent's disconnection of the electricity supply on the two relevant occasions was unlawful; (d) the fact that the first disconnection was for a maximum duration, not normally imposed on a first disconnection, warranted the inference that the disconnection was delayed deliberately; (e) the notices of claim for the arrears of monies claimed by the respondent were followed by the disconnections, again, warranting the inference that the electricity supply would be discontinued or disrupted unless the monies claimed by the respondent were paid up. This was not the legitimate or valid purpose for disconnection of the electricity supply, which again showed a collateral aim which was not supported in law either under the ESA or case law; and (f) the respondent knew or ought to have known that a disconnection of electricity supply to a manufacturer or generator of ice would give rise to great loss and damage to the business, as electricity was the life-blood of such a business. Notwithstanding this, it proceeded with the disconnections, with a view to putting pressure on the appellant to make payment for the arrears it claimed. This was not a lawful method of collecting its debts. Therefore, the conduct of TNB warranted an inference of mala fides. (para 96)

(7) This was, in totality, a fit case for the award of exemplary damages to the appellant. The primary purpose was to communicate to the respondent that it owed a statutory duty to consumers to provide undisrupted electricity as stipulated under the ESA. The established basis for the collection of arrears was to do so as a debt. The respondent could not be allowed to hold electricity to consumers as ransom. Hence, the respondent was in breach of its statutory duty to provide electricity when it disconnected electricity to the appellant. Therefore, the Court of Appeal's decision to refuse the claim for exemplary damages was erroneous. There was sufficient evidential basis to take the facts of this case outside of the general or ordinary line of cases where special and/or general damages sufficed. Therefore, only part of Question 2 was answered in the affirmative, ie a consumer who had been victimised by the respondent by wrongful disconnection of electricity might be entitled to seek exemplary damages, depending on the particular facts of its case, although such a case would be rare. On the other hand, the Court did not agree with the appellant in relation to the latter half of Question 2, that the case of Evergrowth could be relied on for the proposition that exemplary damages could be sought in cases of breach of contract. Having considered the law in full, an expansion of the law on this area was not warranted at this juncture. (paras 106, 110, 111 & 112)

(8) The sole remaining issue was the quantum of exemplary damages to be awarded. The Court of Appeal awarded no exemplary damages at all, but the High Court calculated exemplary damages as a percentage of special damages, ie 25%. In the present case, a sum of RM100,000.00 was appropriate to show the Court's disapproval of the respondent's conduct. In arriving at this figure, the Court took into consideration the respondent's conduct in deliberately disconnecting the electricity supply to an ice-making factory. This, too, was done not once but twice, and these disconnections were undertaken to place extreme pressure on the appellant to make payment of outstanding dues. In these circumstances, the sum of RM100,000.00 was the minimum amount required to signify the Court's disapproval of the respondent's actions. Therefore, in addition to the sum of RM2,907,931.40 and RM652,012.20 for the first and second disconnections, respectively, by way of special damages, the appellant was granted exemplary damages in the sum of RM100,000.00. (paras 115, 119 & 120)

(9) The High Court dismissed the appellant's claim for general damages due to the wrongful interference with its business, causing it to suffer inconvenience and losses, because the Judge held that the appellant had not made out the elements of the tort of wrongful interference with business. The Court of Appeal did not allow the appellant to raise this point as it did not appeal against the dismissal of this claim. The Court of Appeal's decision on this issue was affirmed because the appellant's failure to file an appeal meant that it had accepted the High Court's decision. Further, on a reading of Question 4, the appellant was only pursuing general and/or nominal damages in the alternative to its claim of special damages in respect of the wrongful disconnection of electricity. The sums awarded for special damages in respect of the first and second disconnections of electricity were sufficient to compensate the appellant. It was trite that damages were compensatory in nature and a plaintiff should not be unjustly enriched by an award of damages. (paras 121-122)

Case(s) referred to:

AB v. South West Water Services Ltd [1993] QB 507 (refd)

Asia File Products Sdn Bhd v. Brilliant Achievement Sdn Bhd & Ors [2019] 4 MLRH 161 (refd)

Bonham-Carter v. Hyde Park Hotel Ltd [1948] 64 TLR 177 (refd)

Broome v. Cassell & Co Ltd [1972] AC 1027 (refd)

Brown v. Waterloo Regional Board Of Commissioners Of Police [1982] 37 OR (2d) 277 (refd)

Centennial Centre Of Science And Technology v. US Services Ltd [1982] 40 OR (2d) 253 (refd)

Cheng Hang Guan & Ors v. Perumahan Farlim (Penang) Sdn Bhd & Ors [1993] 3 MLRH 332 (refd)

Conrad v. Household Fire Corporation [1992] 115 NSR (2d) 153 (refd)

George Mitchell v. Finnery Lock (Seeds) Ltd [1983] 1 All ER 108 (refd)

Kuddus v. Constable Of Leicestershire Constabulary [2001] UKHL 29 (refd)

Lee Sau Kong v. Leow Cheng Chiang [1960] 1 MLRA 302 (refd)

Leng Yang Sua & Anor v. Ng Yen Kee & Anor [1985] 1 MLRH 498 (refd)

Lever Brothers Ltd v. Bell [1931] 1 KB 557 (refd)

McIntyre v. Lewis [1991] 1 IR 121 (refd)

Megnaway Enterprise Sdn Bhd v. Soon Lian Hock (No 2) [2009] 2 MLRH 82 (refd)

Menteri Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri, Malaysia & Ors v. Karpal Singh Ram Singh [1991] 1 MLRA 591 (refd)

Ngooi Ku Siong & Anor v. Aidi Abdullah [1984] 1 MLRA 200 (refd)

Ong Ah Long v. Dr S Underwood [1983] 1 MLRA 154 (refd)

Pang Ah Chee (MW) v. Chong Kwee Sang [1984] 1 MLRA 483 (refd)

PH Hydraulics & Engineering Pte Ltd v. Airtrust (Hong Kong) Ltd [2017] SGCA 26 (refd)

Rookes v. Barnard [1964] AC 1129 (refd)

Royal Bank Of Canada v. W Got Associates Electric Ltd M [1999] 3 SCR 408 (refd)

Sambaga Valli KR Ponnusamy v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur & Ors And Another Appeal [2018] 3 MLRA 488 (refd)

Sheikh Jaru Bepari v. AG Peters AIR [1942] Cal 493 (refd)

Sinnaiyah & Sons Sdn Bhd v. Damai Setia Sdn Bhd [2015] 5 MLRA 191 (folld)

Tan Kuan Yau v. Suhindrimani Angasamy [1985] 1 MLRA 183 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Big Man Management Sdn Bhd [2024] 2 MLRA 783 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Chew Thai Kay & Anor [2022] 2 MLRA 178 (folld)

Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) v. Evergrowth Aquaculture Sdn Bhd & Other Appeals [2021] 6 MLRA 501 (distd)

Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Mayaria Sdn Bhd & Anor [2018] MLRAU 501 (folld)

Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Mayaria Sdn Bhd & Anor, Civil Appeal No. 02(f)-28- 03/2017(W) (Unreported) (refd)

Thompson v. Commissioner Of Police Of The Metropolis [1997] 2 All ER 782 (refd)

Thrimalai Palamiappan & Anor v. Mohd Masry Tukimin [1986] 1 MLRH 272 (refd)

Vandervell's Trusts (No 2), Re; White v. Vandervell Trustees Ltd [1974] Ch 269, [1974] 3 All ER 205, [1974] 3 WLR 256 (refd)

Vorvis v. Insurance Corp of British Columbia [1989] 1 SCR 1085 (refd)

Whiten v. Pilot Insurance Co [2002] 1 SCR 595 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Electricity Supply Act 1990, ss 24, 25, 37(1), (3), (4),38(5)

Evidence Act 1950, s 32(1)(b)

Rules of Court 2012, O 59 rr 2, 3, 5(2)

Other(s) referred to:

Lauree Coci, It's Time Exemplary Damages were Part of the Judicial Armory in Contract [2015], UWALawRw 39; [2015] 40(1) University of Western Australia Law Review 1

Malaysian Civil Procedure ("White Book"), Vol 1, 2018 Edn, para 18/7/7

Malaysian Civil Procedure ("White Book"), Vol 1, 2021 Edn, p 905, para 59/3/3

McGregor on Damages, 18th edn, p 428

Nicholas McBride, A Case for Awarding Punitive Damages in Response to Deliberate Breaches of Contract", 24 Anglo-Am. L Rev 369 [1995]

Pollock & Mulla, Indian Contract and Specific Relief Acts, Lexis Nexis Butterworths Wadhwa Nagpur, 13th Edn, Vol II, pp 1521,1522

Counsel:

For the appellant: Logan Sabapathy (Lim Yew Yi & Vivian Oh Xiao Hui with him); M/s Kerk & Partners

For the respondent: Steven Thiru (Hadi Mukhlis Khairulmaini & Gurjeevan Singh Sachdev with him); M/s Steven Thiru & Sudhar Partnership

[For the Court of Appeal judgment, please refer to Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Big Man Management Sdn Bhd [2024] 2 MLRA 783]

JUDGMENT

Nallini Pathmanathan FCJ:

Introduction

[1] The focus of this appeal relates to the assessment and grant of damages, generally. The Appellant, Big Man Management Sdn Bhd ('Big Man') appeals against the decision of the Court of Appeal which did not award any damages to Big Man despite a clear finding of liability against Tenaga Nasional Berhad ('TNB'). For the purposes of this appeal, the two heads of damages that arise for consideration are special damages and exemplary damages.

[2] The basis for the Court of Appeal's decision, in essence, was that Big Man's claim for special damages was not demonstrated or verified. With respect to exemplary damages, the issue was whether such damages can be awarded against a body such as TNB.

[3] The primary issues that arise for our consideration are:

(a) Firstly, to consider the evidential approach to be taken in relation to the proof of special damages. More particularly:

(i) What does the term 'strictly proved' mean?

(ii) How is the evidentiary burden established by the claimant?

(iii) Is such evidentiary burden greater than establishing the claim on a balance of probabilities?

(b) Secondly, with respect to exemplary damages, the issue before this Court relates to whether exemplary damages are claimable by a consumer of electricity in a claim for breach of contract against TNB. Such a claim is to be considered in the context of the distinct facts of the instant case. Here, TNB is a statutory body accorded powers by Parliament to be the sole supplier of the essential utility of electricity to all consumers in the country. The allegation is that as this body has consciously and deliberately acted in excess of the powers granted to it, can exemplary damages for oppressive or arbitrary conduct as envisaged under the first category of Rookes v. Barnard [1964] AC 1129 and extended in Kuddus v. Constable of Leicestershire Constabulary [2001] UKHL 29 be awarded against it? Of particular concern is the position in law where exemplary damages are not generally awarded under the law of contract.

The other issues raised are ancillary to the primary issues above.

Relevant Background

[4] This is a case where Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) disconnected the electricity supply to the premises of an ice-making factory owned by one Ice Man Sdn Bhd ('Ice Man'), operated by Big Man. Prior to the disconnection, TNB discovered meter tampering by the factory but rectified the same. Big Man sued TNB for damages premised on several causes of action:

(a) Wrongful disconnection of electricity;

(b) Trespass on its premises;

(c) Wrongful interference with business;

(d) Defaming Big Man to a third party; and

(e) Breach of statutory duty by disclosing the details of its account to a third party without its consent.

[5] Big Man's claims for trespass, wrongful interference with business, damages, and a breach of statutory duty do not arise for consideration in this appeal.

Questions Of Law

[6] As stated at the outset, the appeal is primarily directed at the Court of Appeal's reversal of the High Court award of damages to Big Man for TNB's wrongful disconnection of electricity. The questions of law in respect of which leave to appeal was granted are:

Q1: Whether the evidential approach of the Court of Appeal with reference to the expression "special damages must be specifically pleaded and strictly proven" stands to be corrected and/or clarified whereby special damages only need be established on a balance of probabilities before a trial court?

Q2: Whether exemplary damages are claimable by a consumer of electricity in a breach of contract claim against TNB, particularly in a case where TNB being a statutory body, has consciously and deliberately acted in excess of the powers granted to the same under statute; and in light of the fact that it is open for TNB to claim for this head of damage as established in Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB) v. Evergrowth Aquaculture Sdn Bhd & Other Appeals [2021] 6 MLRA 501?

Q3: Whether exemplary damages contemplated under the first category of Rookes v. Barnard (i.e., oppressive or arbitrary conduct) can be extended to claims made against statutory corporations following the development of the law by the House of Lords decision in Kuddus v. Constable Of Leicestershire Constabulary [2001] UKHL 29 in extending the first category in Rookes v. Barnard to also private corporations and/or individuals?

Q4: Where a plaintiff has succeeded in establishing liability but fails to prove special damages, whether it is incumbent on a court to award general and/or nominal damages?

Q5: Where a plaintiff has succeeded in establishing liability but fails to prove damages, whether it is open to a court to order substantial costs against the successful party and against event having regard to the principles in O 59, rr 2, 3 and 5(2) of the Rules of Court 2012?

Chronology

[7] At the outset, it is important to comprehend the claim by Big Man.

[8] The chronology of salient events is set out in tabular form below:

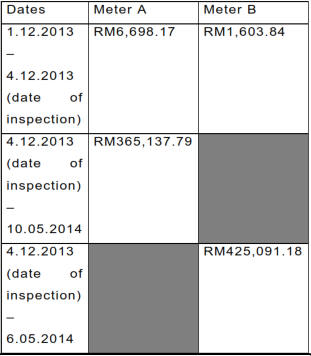

[8] The chronology of salient events is set out in tabular form below:

Date Event - Ice Man owns an ice-production factory which spans 2 lots of land in Johor Bahru. 1.10.2013 Ice Man and Big Man entered into a management contract whereby Big Man would provide management services and handle matters relating to electricity supply to the factory. To this end, Big Man registered 2 electricity accounts with TNB in October 2013. 4.12.2013 TNB inspected the factory premises and found meter tampering. Rectification work was done on both meters. 6.05.2014 TNB inspected the factory premises and found meter tampering. The following rectification work was done on the first meter: 'Tukar armoured cable. Tukar CT[1] ketiga-tiga fasa kerana CT telah terbakar' 10.05.2014 The following rectification work was done on the second meter: 'Tukar armoured cable.' 23.06.2014 TNB issued a notice for the disconnection of electricity that would take place on 24.06.2014. However, the disconnection did not take place as notified. 25.06.2014 TNB issued a notice for the disconnection of electricity that would take place on 26.06.2014. However, the disconnection did not take place as notified. 1.07.2014 TNB issued a notice for the disconnection of electricity. 2.07.2014 TNB disconnected the electricity supply to the factory ('the first disconnection'). 27.07.2014 Big Man received 4 letters of demand from TNB claiming for loss of revenue from meter tampering as follows:

July 2014 Big Man filed Suit 113 against TNB to claim for losses arising out of the first disconnection of electricity. 1.10.2014 TNB resumed supplying electricity to the factory. 15.10.2014 The following rectification work was done on the first meter: 'Tukar meter main. Pendawaian diperbetulkan dan pepasangan disil semula.' 7.01.2015 The following rectification work was done on the second meter: 'Tukar meter baru pada meter utama & meter semak. Pepasangan disil semula.' April 2015 An entity known as Sunshine Merchant Sdn. Bhd. ('Sunshine') intended to purchase Ice Man and negotiated with TNB to resolve the electricity supply issues. 7.04.2015 TNB issued a notice for the disconnection of electricity. 8.04.2015 TNB disconnected the electricity supply to the factory ('the second disconnection'). 14.05.2015 TNB resumed supplying electricity to the factory. 21.05.2015 Sunshine and TNB executed a letter of undertaking. Big Man would withdraw Suit 113 against TNB and Sunshine would settle the loss of revenue claims by TNB against Big Man. However, Sunshine failed to fulfil the letter of undertaking. 1.02.2016 Big Man received 2 letters of demand from TNB claiming for loss of revenue from meter tampering. 15.02.2016 TNB sent 2 disconnection notices to Big Man. 29.02.2016 Big Man filed the present writ of summons in the High Court

[9] It can be seen from the above table that every time TNB inspected the premises and found meter tampering, TNB took steps to rectify the same. That being the case, was TNB entitled to disconnect the electricity to the premises on 2 July 2014 and 8 April 2015? Both the courts below held that TNB was not entitled to do so; hence, the two disconnections were wrongful.

Wrongful Disconnection Of Electricity

[10] Big Man contended that it had no access to the meter room and disavowed any knowledge of, or responsibility for, any alleged tampering with the TNB meters. Big Man further contended that after the alleged tampering had been rectified and was no longer extant, TNB wrongfully used the disconnection of electricity as a means to obtain payment from Big Man on the letters of demand issued by TNB to Big Man for loss of revenue from the meter tampering. This meant that TNB disconnected the electricity for a collateral purpose suggestive of mala fides. This is the basis on which Big Man founded its claim against TNB for exemplary damages.

[11] TNB, however, relied on s 38 of the Electricity Supply Act 1990 (ESA) to contend that it had the right to disconnect electricity, and in the case of repeated meter tampering, it did not lose that right even if the tampering had been rectified and was no longer extant. The High Court held that TNB could not do so, based on the unreported Federal Court decision in Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Mayaria Sdn Bhd & Anor Civil Appeal No 02(f)-28-03/2017(W) ('Mayaria').

[12] On TNB's appeal to the Court of Appeal, this part of the High Court decision was upheld as the Mayaria principle had, by then, been endorsed by the Federal Court in Tenaga Nasional Berhad v. Chew Thai Kay & Anor [2022] 2 MLRA 178 ('Chew Thai Kay'). The Court of Appeal summarised the Mayaria principle thus:

"Once TNB discovers meter tampering and the impugned (tampered) meter is then rectified and/or replaced, then the offence under s 37 of the Act is deemed as no longer subsisting/extant and ceases to exist at the time when the notice of disconnection is issued by TNB to their customer. In those circumstances, TNB cannot invoke s 38(1) of the Act to disconnect the supply of electricity to the consumer's premises. Hence, the disconnection would be unlawful."

[13] The Court of Appeal applied the Federal Court decision of Chew Thai Kay (above) and held TNB liable for wrongfully disconnecting electricity to the factory. However, the Court of Appeal reversed the High Court's award of damages to Big Man on the basis that damages had not been proven. The High Court's order of damages in relation to the wrongful disconnection of electricity was:

(a) Special damages in the sum of RM2,907,931.40 for the loss and damages due to the first electricity cut at its premises (from 2 July 2014 until 1 October 2014);

(b) Special damages in the sum of RM652,012.20 for the second electricity cut (from 8 April 2015 until 14 May 2015);

(c) Exemplary damages in the sum of 25% of the sums of special damages allowed for the 2 electricity cuts, equivalent to RM726,982.85 and RM163,003.05 respectively;

(d) Pre-judgment interest at the rate of 3% p.a. on the first sum of special damages from the last date of the first electricity cut on 1 October 2014 until judgment date (RM436,189.70) and on the second sum of special damages from the last date of the second electricity cut on 14 May 2015 until judgment date (RM85,744.09);

(e) Post-judgment interest at the rate of 5% p.a on the entire judgment sum from judgment date until full settlement.

[14] We shall deal with the issue of special damages, general damages, and exemplary damages in turn, before considering the issue related to the award of costs by the Court of Appeal to TNB.

Special Damages

The High Court

[15] The High Court Judge found that special damages totalling RM2,907,931.40 incurred due to the first disconnection and RM652,012.20 incurred due to the second disconnection were proved and accordingly awarded both these sums. In his judgment at para 92 onwards, the learned High Court Judge found that documents evidencing such loss were tendered by three witnesses, PW-2, PW-7, and PW-8. Further, that such evidence was not discredited either with regard to the first or second disconnection. He also found that such damages arose as a direct consequence of the non-supply of electricity by TNB and that such loss and damage was that "which the parties knew, when they made the contract to be likely to result from the breach of it."

[16] In arriving at this conclusion, the learned judge took into account TNB's contentions discrediting Big Man's evidence, namely that there was insufficient documentary evidence, such as quotations, written notes, receipts, and statements of account. The learned trial judge found, at para 96:

"However, I find that the documentary evidence which was produced before this Court, i.e., the invoices issued and the payment vouchers signed by the vendor company, being conclusive proof of the transaction. This evidence was all marked as exhibits (Exhibits P1(A)-(H), P2(A)-(B), and P3(A)-(H) and not challenged by the Defendant, and I see no reason why I should reject those documents."

The Court of Appeal

[17] The Court of Appeal disagreed. It held that the main focus was the "hefty amount" claimed as special damages, "which must be specifically pleaded and strictly proven." Reliance was placed on the statements of Edgar Joseph Jr SCJ in Cheng Hang Guan & Ors v. Perumahan Farlim (Penang) Sdn Bhd & Ors [1993] 3 MLRH 332. It should be noted that Edgar Joseph Jr SCJ, in this case, did not use the term 'strictly proved' but stated that "where precise evidence is obtainable, the court naturally expects to have it; where it is not, the court must do the best it can. Nevertheless, it remains true to say that generally, difficulty of proof does not dispense with the necessity for proof".

[18] The Court of Appeal took particular note of TNB's grievances with respect to special damages, namely:

The Rental and Purchase of Generators

(i) In relation to the rental and purchase of generators that there was simply insufficient evidence to establish the same. In this context the Court of Appeal accepted TNB's submission that there could not have been a purchase or rental of generators because there was no proof of inquiry, quotation, return notices, receipts and statement of accounts. In short TNB, by adopting this line of questioning and submission, was suggesting that both the rental and purchase of generators was fictitious. However, in accepting TNB's submissions, the Court of Appeal failed to consider the following matters:

(a) In two photographs produced by TNB of the Ice Man's factory, a part of a generator is visible. The fact that generators were actually in use at the premises is supported by the evidence of PW-2, Lim Yong Chiang, a Director of the supplier of generators to Ice Man. He testified that he had personal knowledge of the transactions between his company and Big Man. He positively identified the generators rented by the company to Big Man in the photographs of the premises taken by TNB, notwithstanding that he only saw these photographs for the first time when giving evidence in Court on 12 April 2018;

(b) There are invoices issued by the supplier Kuang Yi Machinery and payment vouchers by Big Man. They were all adduced in Court during trial and these documents were marked as exhibits. The invoices from Kuang Yi Machinery detail the date and period of supply of generators at the behest of Big Man, as well as the price. These invoices are signed and stamped by both the supplier and Big Man. In short both Kuang Yi Machinery's authorised signature and stamp, as well as the receipt by Big Man of the generator in question, is evidence of rental over the entire period of disconnection, and the subsequent purchase of a single generator;

(c) The authenticity of these invoices is not in dispute. The makers, namely PW-2 and PW-7 (Ser Boon Hwa or James, the General Manager of Big Man) were present in court and identified their signatures on those invoices. There are a total of 8 invoices for the rental and purchase of generators. This documentary evidence together with the oral evidence constitutes the basis for the claim for the rental and purchase of generators. Notwithstanding this evidence, the Court of Appeal held: "And as rightly submitted on behalf of TNB, there is in fact no evidence that the Consumer (i.e., Big Man) had ever used generators (and diesel) for purposes of the ice production business at the premises."

(d) In our view, such material evidence does not bear dismissal on the grounds that it does not substantiate rental and purchase of generators, as found by the Court of Appeal;

(e) To match these invoices, Big Man also produced 8 payment vouchers in support of the claim for recovery of monies for the rental and purchase of generators. The payment vouchers were issued by Big Man. These vouchers prove that a payment process existed which required scrutiny and inspection by a series of employees before payment out to Kuang Yi Machinery. More importantly, there is a signature from the recipient, Kuang Yi Machinery, meaning that there is confirmation of receipt by the supplier of the generators;

(f) The documentary evidence is supported by the oral evidence of PW2 who confirmed signing the "received by" column of the payment vouchers exhibited by Big Man. There was no cross-examination by TNB on this issue;

(g) Further confirmation was provided by another witness PW-7, the General Manager of Big Man, who confirmed that the signature in the "verified by" column of the payment vouchers was his.

Therefore, these vouchers evidence actual payment and receipt of the same by the supplier. They cannot therefore be simply dismissed as bare internal payment vouchers. In this context, the conclusion of the Court of Appeal that there is no evidence of actual payment to Kuang Yi Machinery for the rental and purchase of generators is not borne out by the actual evidence. The High Court, in arriving at its conclusion, accepted the totality of the evidence, both documentary and oral and also had the benefit of the audio-visual hearing first-hand. The reversal of that finding was not justified.

Diesel

(ii) In relation to the purchase of diesel to operate the generators for the production of ice, the Court of Appeal held that there was no evidence that Big Man had made payments for the diesel, as no receipts in respect of the purported payments were adduced. However, the Court of Appeal failed to consider the following matters:

(a) A careful perusal of the documentary evidence discloses that there are both invoices and payment vouchers supporting the claims for the purchase of diesel by Big Man. The diesel was supplied by a variety of suppliers who did not testify in Court. However, the General Manager of Big Man PW-7, testified that such payments had been made. In the course of his testimony he produced the relevant supporting documents. The invoices produced in Court were issued by the various suppliers and bear signatures evidencing receipt of the diesel. More importantly there is evidence of receipt of payment through the issuance of specific Public Bank cheques by Big Man. Therefore, the invoices are not bare documents;

(b) These invoices are further corroborated by matching payment vouchers for these purchases of diesel. The payment vouchers make specific reference to the invoice numbers and specify that they comprise payment for the diesel supplied. The payment vouchers bear the words "Being payment of diesel usage of generator use". Additionally, cheque numbers for payment to the diesel suppliers is set out in each payment voucher and matches the receipt of the same as set out in the invoices;

(c) Such evidence for the supply of diesel is further fortified by Ice Man's cheque stubs which also specify that these cheques were issued towards payment of diesel. (Big Man subsequently reimbursed Ice Man for such payments);

(d) The entirety of the diesel documentation amounts to evidence of how the business of Ice Man was conducted when TNB wrongfully terminated the supply of electricity. As records of the business, generated during the course of business these documents are admissible under, inter alia, s 32(1)(b) of the Evidence Act 1950. Taken in its entirety there is a full record of supply of and payment for diesel supplied during the period when the electricity was unlawfully cut off by TNB. There was no relevant cross-examination which had the effect of impugning or discrediting these documents as being fictitious or fabricated records. In these circumstances these documents ought not to be dismissed out of hand;

(e) The statement by the Court of Appeal that there was no evidence that Ice Man had ever used diesel for the generators to make ice at its premises is, in the light of this evidence, with respect, not tenable. The evidence adduced discloses a consistent trajectory of business operations during the period when electricity was not available. The documents are not simply random invoices and payment vouchers but are inter-connected. A consideration of the entirety of the documentary evidence discloses a pattern of supply and receipt of the machinery and diesel required to maintain the business during the period of the electricity cut;

(f) It bears reiterating that TNB, as recognized by the High Court, was not able to discredit the witnesses or the documentation. During cross-examination it was not put to, nor suggested to the relevant witnesses that this documentary footprint was made up or fictitious. When such a large volume of documentary evidence adduced in Court and supported by oral evidence is dismissed outright as being insufficient for proof of the matters stated therein, it follows that such rejection can only be premised on the inference that the entirety of the evidence is made-up or fictitious. However, this was never suggested to any of the witnesses. In these circumstances, the rejection of the evidence as a whole by the Court of Appeal is not warranted;

(g) It was also submitted by TNB that diesel purchased for use for the generators to generate electricity to make ice were actually used for Big Man's lorries. However, there was no evidential basis for TNB's submission. Notwithstanding this, the Court of Appeal appears to have accepted this submission. In doing so, the Court of Appeal failed to consider the refutation by Big Man that re-fuelling of the lorries was undertaken at petrol stations using "indent" cards which allowed Big Man to enjoy subsidised prices for diesel for the lorries. This was evident from PW-7's evidence which was not refuted. Accordingly, the trial judge accepted that the documents produced in this regard were in fact for use for the generators and not the lorries. There was no reason therefore to reverse this finding of fact by the trial judge;

(h) The net effect of the decision of the Court of Appeal is to conclude that the disconnection caused no injury to Ice Man and/or Big Man. Would it be correct to conclude on the entire volume and chain of evidence referred to above, that no loss whatsoever was suffered? Particularly when the trial court, which enjoyed the audio-visual advantage, arrived at a different conclusion? Further, where the cross-examination did not establish that the substantial and material records of business documentation adduced by Big Man, coupled with oral evidence is insufficient, or alternatively a fabrication made up for the purposes of claiming damages?

Indemnity

(iii) Finally in relation to the compensation of RM1,536,25.00 paid by Big Man to Ice Man, TNB contended that there was insufficient evidence to show that this sum had in fact been paid.

The starting point for proof of this claim is the Management and Administrative Services Agreement dated 1 October 2013. Big Man carried out the administration and directed the operations of the factory. Clause 7 of this agreement provides that if there was any disruption to the operation of Ice Man, Big Man was liable for any losses that arose and had to indemnify Ice Man.

[19] The Court of Appeal held that the witness on this evidential point, PW-8, could not show actual proof of payment. (Goh Tack Lik, PW-8, was the CEO of Big Man as well as a shareholder and Director of Ice Man). Therefore, it was concluded that, as there was no proof of actual payment of compensation by Big Man to Ice Man, this claim could not be allowed.

[20] The Court of Appeal further pointed to the close relationship between Big Man and Ice Man as the basis for rejecting the claim. In short, the Court of Appeal was of the view that no compensation had in fact been paid out. Therefore, Big Man's claim was not allowed.

[21] PW-8, Goh Tack Lik, is a Singaporean businessman, aged 64 at the time of the High Court suit. As stated above, he is the CEO of Big Man and a shareholder and Director of Ice Man. In the course of cross-examination, PW-8 said that he was the decision maker for both Big Man and Ice Man. It is apparent from his testimony that he left the day-to-day running of the factory to PW-7, the General Manager of Big Man.

[22] PW-8's evidence was that he personally advanced money from an affiliated company in Singapore, one Unitat, to Big Man, to indemnify Ice Man. From the evidence, it is apparent that Big Man and Ice Man are closely connected. The evidence on record further discloses that it was PW-8 who transmitted the monies.

[23] Big Man was the account holder of TNB. As the companies are closely connected in terms of PW-8's holding as shareholder and Director in Ice Man, and CEO of Big Man, a failure to reimburse Ice Man would necessarily be within the knowledge of PW-8. His evidence is that the monies were paid to Ice Man.

[24] In this context, PW-8 explained how the monies were transferred from Singapore, where he resides, to Malaysia. He explained that the monies were paid in cash and remitted to Ice Man. This is what he said:

"Yes, because the transaction is all by money changers. They deal with cash only. You give them the money; they will bank in the account for you."

[25] In summary, his testimony was that he withdrew cash, which he handed to the Singaporean money-changer, who would then ask the Malaysian counterpart to bank the monies into Big Man's account. Then this money would be remitted by Big Man to Ice Man to make the requisite compensation payment.

[26] His testimony was not challenged on this point, so as to suggest that no payment was actually made by Big Man to Ice Man. The High Court accepted PW-8's evidence as being credible.

[27] Again, as the High Court had the advantage in relation to the demeanour and credibility of the witness, it appears that the Court of Appeal's conclusion that the evidence of "PW-8 did not stand up to curial scrutiny and was questionable" is not, in our view, justified. This is because it is clear from a holistic appreciation of the volume and chain of evidence, as well as the operations of Ice Man and Big Man, that this was the mode of operation of the two companies, probably due to their intertwined nature. Ice Man, as specified in the agreement, indemnified Big Man for losses suffered during the period when the electricity was unlawfully disconnected by TNB.

[28] Given the totality of the evidence, there was insufficient basis for the reversal of the decision of the High Court.

Conclusion On The Evaluation Of Evidence For The Assessment Of Damages

[29] It is pertinent to note that the exercise of determining the measure of damages due to a claimant is neither a robotic mechanical exercise, nor an arbitrary quantum picked out capriciously, nor a measure determined by a judge's intuition or instinct as to what the judge thinks it ought to be.

[30] Most importantly, it is necessary to closely examine and evaluate the documentary and oral evidence before deciding to exclude it in its entirety. Evidence on record ought not to be rejected outright nor ignored where, as in this case, it is sufficient to establish a basis for the claim. An appellate court ought to be slow to reverse a finding of fact which is premised on such a chain of evidence, unless it is patently clear that the documents are a sham or fictitious.

[31] In these circumstances, we find that Big Man discharged its evidentiary burden of proof in relation to its claim for special damages on a balance of probabilities.

The Law

Special Damages

[32] We now turn to the first question of law referred to us, which, in turn, requires us to consider:

(a) Firstly, what the term 'strictly proved' means in law; and

(b) Secondly, whether the evidentiary burden when claiming special damages is greater than a balance of probabilities.

[33] To our minds, the term 'strictly proved' requires the claimant to provide clear, robust, and convincing evidence to establish both the fact and quantum of the damages claimed. This, in turn, means that the claim is quantifiable, not speculative, and is reasonably certain in terms of computation/calculation.

[34] There must be a causal link between the acts or omissions of the wrongdoer and the damages claimed. This is clearly established in the instant case as the disconnection of the electricity supply resulted in the factory not being able to manufacture ice. By way of mitigation, Big Man procured generators and diesel to enable the continued operation of the factory. If it had not, the quantum of loss would, arguably, have been considerably greater. This was not recognized by the Courts below. To our minds, special damages, as we have concluded, were made out.

[35] Reverting to the question at hand, we are of the view that the use of the word 'strictly' does not add, either in substance or form, anything further than what we have identified as being necessary to establish a claim for special damages. What it does mean is that the claimant has to prove its claim in accordance with the provisions of the Evidence Act 1950.

[36] Learned counsel for Big Man provided a useful overview of the phrase "special damages must be strictly proved". It is often taken to refer to an evidential burden higher than that of the usual civil standard on a balance of probabilities, which is not correct. How did this misconception arise?

[37] In 1948, Lord Goddard CJ in Bonham-Carter v. Hyde Park Hotel Ltd [1948] 64 TLR 177 ('Bonham-Carter') decided a claim for damages for theft of a hotel guest's items from her hotel. His judgment is the origin of the phrase that special damages should be "strictly proved". Lord Goddard CJ held as follows:

"Plaintiffs must understand that if they bring actions for damages it is for them to prove their damage; it is not enough to write down the particulars, and, so to speak, throw them at the head of the Court, saying: "This is what I have lost; I ask you to give me these damages." They have to prove it."

[38] It is pertinent that this passage did not use the term "strictly proved". What can reasonably be gleaned from the above statement is that it is insufficient to merely write down the particulars of the loss alleged to be suffered. It is incumbent on the party seeking the damages to prove the same and not simply itemize the claim.

[39] However, after that, a spate of Malaysian cases held that special damages must be "strictly proved". Learned counsel for Big Man tabulated these cases (see Lee Sau Kong v. Leow Cheng Chiang [1960] 1 MLRA 302; Ong Ah Long v. Dr S Underwood [1983] 1 MLRA 154; , Pang Ah Chee (M W) v. Chong Kwee Sang [1984] 1 MLRA 483; Ngooi Ku Siong & Anor v. Aidi Abdullah [1984] 1 MLRA 200; Tan Kuan Yau v. Suhindrimani Angasamy [1985] 1 MLRA 183; Leng Yang Sua & Anor v. Ng Yen Kee & Anor [1985] 1 MLRH 498. A perusal of these cases discloses that the Courts required, as a matter of course, that special damages must be "strictly proved", although not all those cases expressly referred to Bonham-Carter (above). We note, however, that those phrases were used in the courts' judgments, but there is no indication in any of those cases that "strictly proved" connotes a higher standard of proof than the normal civil standard.

[40] In 1986, Mahadev Shankar J (as His Lordship then was) went further than the foregoing case law and held in the High Court road accident case of Thrimalai Palamiappan & Anor v. Mohd Masry Tukimin [1986] 1 MLRH 272:

"Special damages must be strictly proved. The evidentiary burden goes beyond establishing the claim on a mere balance of probabilities. The figure put forward for special damages must come as close to mathematical certainty as the circumstances of the case would allow."

[Emphasis Added]

[41] This then became the basis for subsequent cases to utilise this seemingly 'higher' standard of proof. None of the subsequent other cases have explicitly stated that the standard of proof for special damages is higher than the balance of probabilities. However, it would appear that many courts hold the standard of proof for special damages to be a higher standard than the usual civil standard. This is incorrect. We reaffirm that the standard of proof in all civil cases, including damages, is that of a balance of probabilities (see Sinnaiyah & Sons Sdn Bhd v. Damai Setia Sdn Bhd [2015] 5 MLRA 191).

[42] As to the quality of evidence required to satisfy the evidential burden, it is trite that it is not necessary to prove each and every element of the loss with scientific precision. This may often simply not be possible. The Court is bound to do the best it can based on the evidence before it on record.

Conclusion On Special Damages

[43] We therefore reverse the finding of the Court of Appeal that Big Man failed to prove special damages. The Court of Appeal erred in rejecting the documentary evidence outright. Therefore, we reinstate the High Court's award for special damages for the first and the second disconnections with interest.

[44] We turn to the relevant question of law:

Q1: Whether the evidential approach of the Court of Appeal with reference to the expression "special damages must be specifically pleaded and strictly proven" stands to be corrected and/or clarified whereby special damages only need be established on a balance of probabilities before a trial court?

Answer: It is trite that special damages in a civil claim need only be established on a balance of probabilities. The phrase "strictly proved" does not denote that evidence is bound to be adduced to a greater degree than the balance of probabilities. This means that the term 'strictly proved' in relation to the evidentiary burden does not increase such burden in any manner otherwise than to require that it meets the civil standard of proof.

[45] As questions 4 and 5 are premised on the basis that Big Man failed to prove special damages, it is not necessary to answer the same.

Exemplary Damages

[46] At the outset, it is necessary to deal with TNB's submission that Big Man did not pray for exemplary damages. We find that Big Man expressly prayed for exemplary damages at para 11(m) of the amended Statement of Claim.

[47] We shall now discuss the law on exemplary damages. First, it must be noted that with regard to the term 'exemplary damages' and 'punitive damages', their usage differs according to jurisdiction, hence the different terminology in the extracts we have taken from case law and textbooks below.

[48] Nicholas McBride in an article "A Case for Awarding Punitive Damages in Response to Deliberate Breaches of Contract", 24 Anglo-Am. L. Rev. 369 [1995] advocates for the use of the term 'punitive damages' because whichever term is used, the award made is aimed at punishing the defendant for his deliberate wrongdoing, not at making an example of the defendant pour encourager les autres (literally "in order to encourage the others" but used ironically to mean "as a warning to others").[2]

[49] Lauree Coci in an article titled "It's Time Exemplary Damages were Part of the Judicial Armory in Contract" [2015] UWALawRw 39; (2015) 40(1) University of Western Australia Law Review 1 stated: "Exemplary damages are sometimes referred to as punitive, penal, retributive and vindictive damages. However, the term 'exemplary damages' has found judicial favour in Australia...". Likewise, we will use the term exemplary damages as this is what it is normally called in Malaysia.

[50] Volume II of Pollock & Mulla's text on Indian Contract and Specific Relief Acts (13th Edition, Lexis Nexis Butterworths Wadhwa Nagpur) p 1521 states: "(ii) 'exemplary damages' are intended to make an example of the defendant; they are punitive and not intended to compensate the plaintiff for any loss, but rather to punish the defendant." On the same page, Pollock & Mulla referred to the Report of the (English) Law Commission (Law Com No 247 of 1997) on 'Aggravated, Exemplary and Restitutionary Damages' which recommended that exemplary damages be awarded if the defendant in committing the wrong, or later, deliberately and outrageously disregarded the plaintiff's rights, but should not be awarded for breach of contract.

[51] Pollock & Mulla, at p 1522, further explain exemplary damages as follows:

"Exemplary damages are those awarded against the defendant as a punishment, and hence the assessment exceeds compensation to the plaintiff. These are awarded not to compensate the claimant, nor even to strip the defendant of his profit, but to express the court's disapproval of the defendant's conduct..."

[52] Our discussion will first deal with the issue of whether exemplary damages are indeed available for breach of contract in this appeal.

The Approach Of The Courts Below To Exemplary Damages

[53] The High Court did not consider the legal position relating to an award of exemplary damages in contract. The learned judge relied on cases of tort (primarily trespass and nuisance) to determine that Big Man was entitled to exemplary damages by reason of the wrongful and/or unlawful disconnection of electricity. This does not, to our minds, address the issue of awarding exemplary damages in contract cases.

[54] The Court of Appeal held that exemplary damages cannot be awarded for a breach of contract claim of this type. Among other authorities, the Court of Appeal cited McGregor On Damages (18th Edn), at p 428 for this proposition.

[55] Learned counsel for Big Man provided considerable case law and articles on the subject, urging us to allow for such damages in contract. Learned counsel for TNB contended otherwise and cautioned against the opening of the floodgates. We shall consider the position in UK, Australia, India, Singapore and Canada. In the latter two jurisdictions, exemplary damages are available for breach of contract.

UK

[56] Pollock & Mulla, at p 1522, explain that, in English law, punitive damages are not available for breach of contract but may be recovered if the action is based in tort while, in Canada, punitive damages may be awarded, albeit rarely, in contract cases, referencing the case of Vorvis v. Insurance Corp. of British Columbia [1989] 1 SCR 1085 ('Vorvis'). (We will discuss the Canadian cases below)

[57] However, there have been calls to alter the UK position. We note that in McGregoron Damages (18th Edn), at p 428, the learned author, having rejected the award of exemplary damages in contract law, went on to make this query: "But may not the new limits on exemplary damages have permitted an enlargement of the situations in which awards may be made? Once the rationale has been changed so as to concentrate upon high-handed public conduct and profit-motivated private conduct, may not such conduct deserve the same sanction whatever the cause of action?"

[58] McBride (above) in his scholarly article, argues that punitive damages should be awarded against those who deliberately breach their contractual obligations because punitive damages are awarded in order to punish such persons as:

(a) their behaviour is left unpunished by the criminal law;

(b) a breach of contract constitutes a breach of a common law obligation; and

(c) amounts to an unlawful act (see the dicta of Oliver LJ in George Mitchell v. Finney Lock (Seeds) Ltd [1983] 1 All ER 108, 118h: "... the purpose of a contract is performance and not the grant of an option to pay damages."

[59] Among the pertinent points raised by McBride in support of awarding punitive damages for breach of contract are that both a victim of a tort and the victim of a breach of contract suffer economic harm, and introducing punitive damages for breaches of contract would not affect the certainty of the legal liability of businesses, as punitive damages would not be awarded against businesses as long as they do not breach their contracts in bad faith.

[60] These are some of the arguments supporting a change in the position on exemplary damages for breach of contract in the UK. We turn to Australia, which adopts the same position as the UK.

Australia

[61] In Australia, exemplary damages are only available in tort but not for breach of contract. Like the UK, there are calls to alter the Australian position on exemplary damages to match the Canadian position. The rationale is, as stated above, that there is no reason why exemplary damages are available in tort but not in contract. The argument by Lauree Coci (above) is that the Australian principles for the grant of exemplary damages should align more with Canadian case-law such that exemplary damages should be available for deliberate intentional and reckless breaches of contract.

India

[62] The position in India, too, is much the same as in England and Australia, namely that exemplary damages are generally not at present available for breach of contract. However, that position is evolving — if not yet to breaches of contract. The established position prevails in that damages for breach of contract are compensatory and not punitive.

[63] Pollock & Mulla, at p 1522, does, however, cite the case of Sheikh Jaru Bepari v. AG Peters AIR [1942] Cal 493 for the proposition that where elements of fraud, oppression, malice or the like are found, the court may grant vindictive or exemplary damages by way of punishment to the wrongdoer.

[64] In India, the courts have awarded damages for wrongful disconnection of electricity with insufficient notice to the consumer, but none have awarded exemplary damages. The type of damages awarded is either compensatory damages, or where the plaintiff is unable to prove damages, an award of nominal damages.

Singapore

[65] On the issue of whether punitive damages can be awarded for breach of contract, the Singapore Court of Appeal in PH Hydraulics & Engineering Pte Ltd v. Airtrust (Hong Kong) Ltd [2017] SGCA 26 followed the English position that punitive damages are allowed in tort but not in contract. This is a case where PH designed and supplied a 300 ton Reel Drive Unit (RDU) which would be used by Airtrust to lay undersea umbilical cables in the Bass Straits of Australia. When the RDU failed and had to be repaired, it was discovered that there were problems in its design and manufacture. Airtrust sued PH for breach of the sale and purchase agreement for the RDU, alleging that not only was the unit delivered of poor quality and unfit for its purpose, but PH had also fraudulently secured the relevant certification for the RDU. The trial court found in favour of Airtrust and awarded punitive (exemplary) damages (to be assessed) against PH in addition to compensatory damages. PH appealed to the Court of Appeal that held that PH was grossly negligent at the most but had not acted fraudulently.

[66] The court held that contractual obligations are voluntarily undertaken, but liability in tort is imposed as a matter of policy. Since parties to a contract have decided between themselves what the terms of the contract should be, the courts play a minimal role in regulating their conduct. The court held that there are good reasons for distinguishing between a breach of contract and the commission of a tort in deciding whether to impose punitive damages. Effectively, awarding punitive damages against the party in breach amounts to imposing an external standard because the court is signifying its own outrage at the contract-breaker's conduct and communicating its own view of what proper commercial behaviour should be, instead of giving effect to the standard set by the contracting parties. Andrew Phang JCA held: "Punishment and deterrence are quintessentially part of the legal landscape of the criminal law."

[67] The court refused to adopt the Canadian approach (discussed below), finding that the arguments against awarding punitive damages in a purely contractual contract outweigh the arguments in favour of the same. The court held strong views about the differences between cases of contract and tort to warrant refusing to impose punitive damages for breach of contract. The court therefore imposed a general rule that punitive damages cannot be awarded for breach of contract, but did not completely shut the door in respect of cases where there might occur a particularly outrageous type of breach necessitating a departure from the general rule. However, the court stresses that it would have to be a truly exceptional case, and it would not award punitive damages if there were alternative remedies that the court could have awarded such as damages for mental distress for breach of contract.

Canada

[68] In Canada, the courts do award exemplary damages for breach of contract. The rationale in that jurisdiction is that there is no reason to distinguish between a tort and a breach of contract in awarding punitive damages (see Brown v. Waterloo Regional Board Of Commissioners Of Police (1982) 37 OR (2d) 277 which was affirmed in Centennial Centre Of Science And Technology v. US Services Ltd (1982) 40 OR (2d) 253 and Conrad v. Household Fire Corporation (1992) 115 NSR (2d) 153).

[69] In the case of Royal Bank Of Canada ('Bank') v. W Got Associates Electric Ltd M [1999] 3 SCR 408 ('Got'), the Bank sued Got for a breach of the banking facilities afforded to it. Got filed a counterclaim alleging breach of contract and conversion, premised on the Bank's failing to give Got notice of recalling the loan as required under the debenture, and appointing a receiver. The facts disclose that Got's lawyer only discovered that the Bank was going to initiate receivership proceedings when he accidentally encountered the Bank's lawyer who informed him that he was on his way to court to obtain an order to appoint a receiver. Although the matter was fixed for the following day and Got's lawyer attended the hearing, he had no notice of the bank's actions and was unable to obtain instructions from his client. He was accordingly unable to represent his client properly or fully. The court refused to adjourn the matter, and the receiver took control of the company that very day and, although outside of the scope of the receivership order, terminated contracts and dismissed employees.

[70] The trial judge found the Bank liable for the tort of conversion of the client's assets and awarded compensatory damages, as well as exemplary damages in the sum of $100,000.00 to send a clear message relating to the impropriety of the Bank's grave and irrevocable conduct, as well as its misuse of the judicial system in rushing to foreclose on Got, and misleading the judge to appoint the receiver. The decision was largely upheld on appeal. The Supreme Court of Canada upheld the decision in essence.

[71] More pertinently to the present appeal, the Supreme Court refused to overturn the award of exemplary damages by the trial judge as upheld by the Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court agreed with the trial judge that the conduct of the bank" seriously affronts the administration of justice "but emphasized that an award for exemplary damages in commercial disputes would remain an extraordinary remedy. It was reasoned that while punitive damages are available for a breach of contract, the circumstances that would justify such damages in the absence of actions also constituting a tort would be rare.

[72] In the Canadian case of Whiten v. Pilot Insurance Co [2002] 1 SCR 595 ('Whiten'), again, the circumstances surrounding the grant of exemplary damages for a breach of contract were even more extreme than in Got.

[73] Whiten's family was a victim of a fire and sought to make a claim from their insurers. The fire happened during winter, and the Whiten family fled the house after midnight in their night clothes, the husband suffering serious frostbite to his feet. The insurance company paid Whiten a sum of $5,000.00 for living expenses and a further sum for the rental of a cottage to house the family for a few months. After this, the insurance company cut off support, insisting that the Whiten family committed arson by burning down their own house. This stance was adopted notwithstanding the statements by the local fire chief, the insurance company's own expert investigator and initial expert that there was no evidence whatsoever of arson. The trial was protracted due to the insurance company's confrontational conduct, but their position of arson was discredited at trial. The jury, clearly outraged by the high-handed tactics of the insurance company, awarded compensatory damages and $1 million in punitive damages. A majority of the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal in part and reduced the punitive damages award to $100,000.

[74] The Supreme Court held, by a majority, that the award of $1 million in punitive damages was more than the Court itself would have awarded, but was still within the high end of the range where juries were at liberty to make such assessment. The dissenting judge held that the insurance company's bad faith in the handling of the claim amply justified the award of punitive damages, but the amount of $1 million, which was 3 times the compensation for loss of property, was well beyond a rational and appropriate use of this remedy. There was no need for general deterrence because there was no evidence that such conduct was how the insurance company regularly ran its business or was widespread in the Canadian insurance industry.

[75] The majority decision of the Supreme Court made reference to both Vorvis (above) and Got (above), concluding that in order to justify an award for punitive damages, there had to be an actionable wrong, which was separate from the primary contractual breach of contract. The Supreme Court found that the separate actionable wrong in that case was a breach of the contractual duty of good faith. This breach, it was held, was independent of, and in addition to, the breach of contractual duty to pay the loss, and so constituted an "actionable wrong." As held in Vorvis (above), the separate actionable wrong did not need to be an independent tort.

[76] In this context, the majority held as follows:

" To require a plaintiff to formulate a tort in a case such as the present is pure formalism. An independent actionable wrong is required, but it can be found in breach of a distinct and separate contractual provision or other duty such as a fiduciary obligation."

[77] The principle that may be drawn from the Canadian case law is that exemplary damages can be awarded for breach of contract. Such damages are only to be awarded for egregious conduct in rare cases, where there is another actionable wrong in addition to the breach of contract.

Present Appeal

[78] Returning to the facts of the present case, it is not in dispute that TNB wrongfully disconnected the electricity supply to the premises of Big Man in order to force it to settle its outstanding bills. Both the courts below were unanimous that TNB was liable for such wrongful disconnection of electricity. However the question that arises for consideration is whether there is basis on the facts of this case warranting an expansion of the law to allow for the grant of punitive damages or exemplary damages when such an extension is not warranted.

[79] We find that in this case, TNB had a statutory duty to provide electricity to Big Man. Section 24 of the ESA 1990 provides such a duty as follows:

(a) The Federal Constitution in the Federal List in the Ninth Schedule prescribes that an entity or statutory body is to ensure provision of electricity, a fundamental and necessary utility to all citizens of the nation. TNB is the single body that is so entrusted under the Federal Constitution to do so for Peninsular Malaysia. Put another way, TNB holds the monopoly on the supply of electricity and as a public authority it has a duty to supply electricity to the public. Pursuant to the obligation imposed under the Federal Constitution, the Electricity Supply Act ('ESA') makes statutory provision for such needs. In this context, s 24 is relevant:

24. Duty to supply on request

(1) Subject to the following provisions of this Part and any regulation made thereunder, a licensee shall upon being required to do so by the owner or occupier of any premises-

(a) give a supply of electricity to those premises;

and

(b) so far as may be necessary for that purpose, provide supply lines or any electrical plant or equipment.

[Emphasis Added]

[80] The duty is subject to exceptions under s 25 ESA 1990, none of which are present in this case. The extent of such duty is clearly set out in case law:

(a) Per Azahar Mohamed FCJ in Chew Thai Kay (above): "Electricity is a basic necessity and the lifeblood of businesses." In that decision, His Lordship approved Mayaria (above);

(b) In Mayaria (above), David Wong Dak Wah CJSS (as he then was) stated:

"We agree with the COA's interpretation of s 38(1) & s 38(3) in case no 9 — Mayaria case that the power of disconnection is lost once the temper meter is rectified. Our reasons inter alia are these:

1) We cannot find in the Act any provision which departs from the normal way of recovering debts by pursuing a civil action in Court. Any departure from this substantive right of the defendant to seek refuge in the court of law must be made clear by the legislature. In this case, we are asked to read into the Act that the plaintiff in this case TNB can use an act of threat-the power of disconnection to recover its loss of revenue. With respect, we cannot find such clear words in the Act which takes away the rights of the consumer to seek refuge to dispute the amount claimed. In fact we agree with the learned counsel of the respondent when he says the power to disconnect is subject to the right to recover as provided by s 39(5) of the Act.

2) TNB holds the monopoly on the supply of electricity and as a public authority it has a duty to supply electricity to the public. It is not significant that the power of disconnection is only for 3 months and not for until the consumer pays of the loss of revenue by the tempering. Further, that disconnection can be done even if there is no conviction of an offence by the consumer. To further allow TNB to use the threat of disconnection to recover the loss of revenue would be giving TNB untrammeled powers to disconnect electricity which is contrary to the very notion of TNB holding a monopoly supply of electricity to the country."

[Emphasis Added]

[81] It therefore follows that TNB's unlawful disconnection caused considerable damage to Big Man. However, it is argued by TNB that Big Man did not plead any tortious cause of action in this context, nor a breach of statutory duty. Therefore, TNB maintains, a claim for damages, particularly exemplary damages, has no proper foundation in the recognised categories of law allowing for such grant, in this jurisdiction.

[82] Any such grant would open the floodgates in allowing for the grant of exemplary damages in contract.

Is Big Man's Claim Premised Solely On Breach Of Contract, Or Is There Basis For A Claim Based On A Breach Of Statutory Duty?

[83] But this brings to the fore a primary question. Is the entire claim of the Plaintiff premised solely on contract? Or does it contain sufficient material facts related to any other cause of action, be it in tort or breach of statutory duty?

[84] Therefore, the first issue that arises for consideration is whether there is a plea of a wrongful disconnection by TNB in breach of its statutory duties, giving rise to grave loss and damage to the Plaintiff, Big Man. It is trite that only material facts are pleaded, not the law nor evidence.

[85] A perusal of the Statement of Claim discloses that:

(i) At para 9, the Plaintiff details that TNB issued notices of disconnection of electricity to Big Man, stating that it was of the view that an offence had been committed by Big Man under the ESA 1990 under ss 37(1), 37(3) and 37(4). This establishes that the statute and specific provisions of the ESA comprised the basis for TNB to seek to disconnect the electricity supply to Big Man's ice business. Therefore, the statute underlies the basis for the Statement of Claim;

(ii) The subsequent paragraphs declare the subsequent notices of disconnection issued, again under the ESA;

(iii) In paras 18 and 19 of the Statement of Claim Big Man pleads the various bills and claims issued by TNB making claims for arrears of monies due and owing under s 38 of the ESA. Again, there is clear reference to the ESA as a statute underlying and comprising a basis for Big Man's claim against TNB;

(iv) Paragraph 20 specifies the disconnection of the electricity supply (notwithstanding rectification) which sets out the claim that the electricity was disconnected to enable collection of arrears of the monies claimed by TNB. This is followed by the damage suffered by Big Man in its ice business and the steps it took to mitigate such loss;

(v) At paras 25 and 26, Big Man pleads that the powers given by Parliament to TNB were to disconnect electricity supply to avoid ongoing losses. But when the supply was disconnected the losses had been rectified. Any such disconnection is undertaken under the ESA. Therefore, the notices of disconnection after rectification was invalid. This plea establishes a breach of the provisions of the statute relating to the supply of electricity, namely the ESA. Accordingly, there is a plea of the material facts showing a breach of the statute — namely a breach of the duty or obligation owed by TNB to the consumer, Big Man. It cannot therefore be stated conclusively that there is no plea of a breach of statutory duty in the instant claim. Such a plea subsists on a holistic reading of the claim particularly paras 25 and 26;

(vi) The same plea is made in paras 33-35 of the Statement of Claim in relation to the second disconnection;

(vii) Paragraph 55 is a plea by Big Man that TNB acted outside the scope of its jurisdiction without the consent of the plaintiff, Big Man which destroyed or impaired Big Man's rights under the ESA and its ancillary regulations. Big Man relied on the facts and particulars stipulated in the claim itself. In essence Big Man further pleaded that as a result of these matters, TNB caused loss to the plaintiff by unlawful means. This again amounts to a plea of a statutory duty under the ESA.

[86] It should be borne in mind that so long as the facts as pleaded give rise to a cause of action in a breach of statutory duty, that is a sufficient basis to construe a cause of action in the claim. The fact that it may not be pleaded expressly, as found in a textbook, does not detract from the existence of the cause of action in the pleading.

[87] This is supported by the English Court of Appeal case of Vandervell's Trusts (No 2), Re; White v. Vandervell Trustees Ltd [1974] Ch 269, [1974] 3 All ER 205, [1974] 3 WLR 256, 118 Sol Jo 566 ('Vandervell's Trusts (No 2)'). All three appellate judges wrote judgments, two of which are of relevance to the present issue.

[88] We quote first from the judgment of the chairman, Lord Denning M.R., who at pp 321-322, stressed the point that it is not necessary for the pleadings to state the legal result as long as the pleadings contain all material facts:

"The pleadings