High Court Malaya, Kuala Lumpur

Gan Techiong JC

[Civil Appeal No: WA-12BNCvC-77-07-2024]

27 February 2025

Banking: Banker and customer — Remittance by appellant, erroneously credited into accounts of third parties instead of beneficiary/payee's account despite beneficiary/payee's name having been validated — Whether respondent entitled to rely on exclusion clause in remittance form to avoid liability for monies erroneously credited into overseas bank accounts of parties whose names and account numbers differed from name and account number stated in remittance form — Whether exclusion clause void by virtue of s 29 Contracts Act 1950 — Whether respondent breached terms of contract with appellant

Contract: Breach — Monies remitted by appellant erroneously credited into accounts of third parties instead of beneficiary/payee's account despite beneficiary/payee's name having been validated — Whether respondent entitled to rely on exclusion clause in remittance form to avoid liability for monies erroneously credited into overseas bank accounts of parties whose names and account numbers differed from name and account number stated in remittance form — Whether exclusion clause void by virtue of s 29 Contracts Act 1950 — Whether respondent breached terms of contract with appellant

The appellant was a customer of the respondent bank and sought to remit the purchase price for face masks that it had purchased from a supplier, Ali B Beheer BV. The appellant duly filled in the respondent's Remittance Form and stated therein the name of the beneficiary/payee, Ali B Beheer BV, and that its bank account was with ING Bank in the Netherlands ('ING Bank'). The appellant subsequently discovered that the remittances were erroneously credited into the bank accounts of third parties instead of the bank account of Ali B Beheer BV. ING Bank refunded only 25% of the monies through the respondent. The respondent relied on the exclusion clause in its Remittance Form to deny any liability and declined to pursue any claim against its agent/intermediary banks and/or ING Bank. The Sessions Court held, inter alia, that the terms and conditions of the Remittance Form, particularly the exclusion clause, were applicable to restrain the appellant from suing the respondent. Hence the instant appeal. The appellant submitted that the respondent was in breach of contract in that the monies debited from its account were not credited into the account of the beneficiary/payee named in the Remittance Form. It was also contended that based on cl 9 of the terms and conditions printed at the back of the Remittance Form, the respondent could rely solely on the account number to effect a remittance if and only if it was an Interbank Giro Remittance ('IBG'), and that the subject transaction in this instance was not such an IBG transaction. Relying on CIMB Bank Berhad v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke & Anor (CIMB Bank v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke) the appellant submitted that the exclusion clause was void by virtue of s 29 of the Contracts Act 1950 ('CA 1950'). The respondent submitted that by virtue of cl 8 printed on the back of the Remittance Form, telegraphic transfers were sent entirely at the applicant/appellant's own risk and that neither it nor its branches, correspondents and agents were liable for any consequence. The respondent further submitted that it did not have a duty of care to check and/ or to give notice to and/or inform ING Bank to match the account number and name of the beneficiary/payee for telegraphic transfers.

Held (allowing the appeal):

(1) Given that cl 9 was drafted to state that only IBG transactions should be based solely on one identifier, ie the account number of the beneficiary/payee stated in the Remittance Form, it was fair, reasonable and logical to construe cl 9 as intended to mean that remittance transactions other than IBG ones, would still be transacted based on other identifiers, including the name of the beneficiary/payee, to identify the recipient's bank account. (para 45)

(2) Applying the principle of expressio unius est exclusio alterius, the clause was to be fairly and reasonably interpreted in favour of the appellant, ie that the respondent agreed to perform the remittances based on both the name and account number of the beneficiary/payee. (paras 46-47)

(3) Unless clearly stipulated by the respondent that telegraphic transfers should be based solely on the account number, the beneficiary/payee's name must be deemed a mandatory identifier. The contra proferentem rule also applied, which would result in an interpretation against the respondent because the terms and conditions in the Remittance Form were imposed by the respondent on its customers. (paras 48 & 61)

(4) The name of the beneficiary/payee, ie Ali B Beheer BV having been validated by the respondent, was an identifier which the respondent ought to have stipulated when instructing its intermediary/agent banks. The failure to do so constituted a breach of contract and the respondent was therefore liable to repay the said funds to the appellant. (para 54)

(5) Based on the decision in CIMB Bank v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke, the exclusion clause relied upon by the respondent was invalid under s 29 of the CA 1950. It was unconscionable for the respondent to avoid liability by relying on such a clause that left the appellant with no recourse. (paras 60-61)

Case(s) referred to:

CIMB Bank Berhad v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke & Anor [2019] 1 MLRA 599 (folld)

Koike (M) Sdn Bhd v. CIMB Bank Berhad [2018] MLRHU 1001 (distd)

Public Bank Berhad & Anor v. Exporaya Sdn Bhd [2012] 6 MLRA 466 (distd)

Tidal Energy Ltd v. Bank Of Scotland Plc [2015] All ER 15 (distd)

Legislation referred to:

Contracts Act 1950, s 29

Counsel:

For the appellant: Ong Kim Hong; M/s Ho & Ho

For the respondent: Marianne Loh Suet May (Megan Phang Yuet Yee with her); M/s Shook Lin & Bok

JUDGMENT

Gan Techiong JC:

Introduction

[1] If all commercial banks in Malaysia are to impose the same exclusion clause as the Respondent Bank in this case when handling overseas remittances for their customers, there is much for the customers to worry about. This is so because the Respondent Bank takes the position that it is entitled to rely on exclusion clauses in its Remittance Form to disclaim all liabilities if the customer's money had been erroneously credited into the bank account of someone whose name is completely different from the beneficiary/payee's name stated in the Remittance Form.

[2] In reply to my question during the hearing of this appeal, learned counsel for the Respondent Bank confirmed the bank's position is that it would disclaim liability even if the remitted money had been erroneously credited into a bank account overseas belonging to someone whose name and account number are completely different from the name and account number stated in the Remittance Form. This revelation triggered audible gasps from the Bar Table and public gallery of this Court. The bank's position is that it would "do its best" to assist the customer to request a refund from overseas but would disclaim liability.

[3] In this case, the Respondent Bank's Remittance Form, which was duly filled in by the customer (the Appellant Customer), stated the name of the beneficiary/payee as "ALI B BEHEER BV" and its bank account is with ING Bank in the Netherlands. However, the remitted money, by way of 3 tranches, ended up being credited by ING Bank into bank accounts belonging to Hr M Masseling, Mw NR Suleman and Hr A Nour respectively.

[4] The details shall be discussed below. Suffice for now, to highlight that ING Bank refunded only about 25% of the customer's money through the Respondent Bank, and the Appellant Customer was told to go to the Netherlands to sue those 3 persons who received its money.

[5] There are two main issues that arise in this case; the first is whether the Respondent Bank has breached the terms of its contract with its customer (the Appellant) because even though the bank account of the beneficiary/payee stated in its Remittance Form has not been credited with the money remitted by its customer, the Respondent Bank had refused to reimburse the customer. The second issue is whether the Respondent Bank is entitled to rely on the exclusion clause stated in its Remittance Form.

[6] After reserving the decision to consider those two issues and reading the authorities cited by learned counsel, I decided that this Court ought to allow the customer's appeal and hold the bank liable. My reasons are as set out below.

Background Facts

[7] The Appellant/Plaintiff (hereinafter referred to as "the Appellant Customer") is a company incorporated in Malaysia while the Respondent/Defendant (hereinafter referred to as "the Respondent Bank") carries on banking business in Malaysia.

[8] The Appellant Customer is a customer of the Respondent Bank.

[9] In March 2020, when the whole world was stricken by the Covid-19 virus which led to the Government making it mandatory to wear face masks, the Appellant Customer decided to import a large quantity of face masks from the Netherlands — hoping to profit from the sudden surge in demand for face masks.

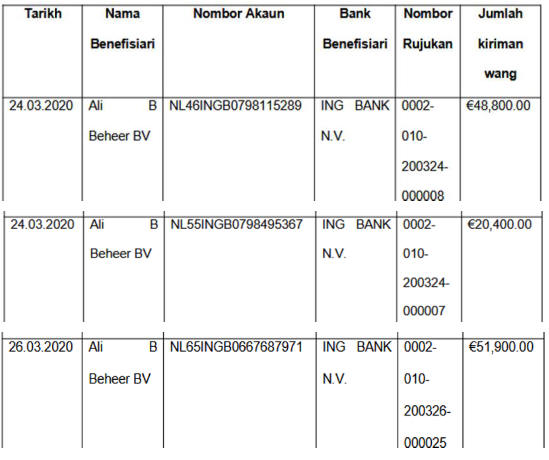

[10] The Appellant Customer found a supplier by the name of ALI B BEHEER BV whose place of business is in the Netherlands, and decided to purchase 3 consignments of face masks from the said supplier. The ensuing events were visits to the branch of its banker (the Respondent Bank) on 24th and 26 March 2020 to remit the purchase price to the supplier ALI B BEHEER BV. The Appellant Customer was instructed by the supplier to pay into three different accounts, all bearing the same name of ALI B BEHEER BV. The details of those remittances are as pleaded in the Appellant Customer's Amended Statement of Claim, a screenshot of which is pasted below:

[11] The total amount of money remitted, in Euro currency, was €121,100.00, and the Respondent performed the three remittances by debiting a total of RM584,567.00 from the Appellant Customer's bank account.

[12] As overseas remittances, such as those in this case, ought to result in the beneficiary/payee's bank account being credited within 3 days, the Appellant Customer was alarmed when informed by the vendor ALI B BEHEER BV that the remittances effected on the 24th had yet to be received as at 27 March 2020.

[13] As 27 March 2020 was a Friday, the Appellant called the Respondent Bank to enquire, and followed up on the next working day Monday 30 March 2020, with instructions to recall the remittances ("recall" is a terminology used by the Respondent Bank).

[14] As for the proceedings filed, the Appellant Customer had initially sued both the Respondent Bank and ING Bank. However, on 21 September 2020, the Court of Appeal struck out the Appellant Customer's writ against ING Bank on the ground that the cause of action by the Appellant against ING Bank "is substantially in the Netherlands, and the Netherlands would be the appropriate forum".

[15] Other correspondences between the parties are irrelevant because the crux of the case is that those three remittances had been erroneously credited by ING Bank in the Netherlands into the bank accounts of Hr M Masseling, Mw NR Suleman and Hr A Nour respectively instead of into the bank account of ALI B BEHEER BV and only RM150,063.13 had been refunded by the Respondent Bank to the Appellant Customer (leaving a balance of RM434,503.87 unrefunded) but the Respondent Bank takes the position that it is entitled to decline to pursue a claim against its agent banks and/or ING Bank, and to shut the door on the Appellant Customer by relying on exclusion clauses.

The Appellant Customer's Position

[16] First, the Appellant Customer's counsel referred to the format of the "Remittance Application Form" used by the Respondent Bank for its customers to fill in for the purpose of instructing the bank to remit money. It was highlighted that every remittance is subject to the terms and conditions stated at the back of the Remittance Application Form (hereinafter referred to simply as "the Remittance Form"). Its format is such that there are 8 sections therein to be completed by the Appellant Customer, including the name and address of the beneficiary/payee and his account number.

[17] It was further submitted that the Respondent Bank was in breach of contract because the money debited from the Appellant Customer's account was not credited into the account of the beneficiary/payee named in the Remittance Form, which is ALI B BEHEER BV.

[18] Learned counsel for the Appellant Customer contended that based on cl 9 of the terms and conditions printed at the back of the Remittance Form, the Respondent Bank may rely solely on the account number to effect a remittance if and only if it is an Interbank Giro (IBG) remittance. He stressed that the subject transaction was not an IBG remittance and that since only IBG transactions are expressly mentioned, telegraphic transfers were not based solely on the beneficiary/payee's account number. The said cl 9 reads:

"9. For IBG transactions, the credit to the beneficiary's account will be based solely on the account number given by the applicant."

[19] The Appellant Customer's counsel went on to submit that the learned Sessions Court Judge had erred in upholding those exclusion clauses printed at the back of the Remittance Form, in disregard of the legal principles pronounced in the judgment of the Federal Court in CIMB Bank Berhad v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke & Anor [2019] 1 MLRA 599. He submits that it is an authority applicable to the facts of this case to render the exclusion clauses void by virtue of s 29 Contracts Act 1950.

The Respondent Bank's Position

[20] Learned counsel for the Respondent Bank submitted that the telegraphic transfers were effected in accordance with the instructions of the Appellant Customer based on the information provided in the Remittance Forms. The following sums were debited from the Appellant Customer's bank account to be remitted into the accounts of one ALI B BEHEER BV maintained with the ING Bank in the Netherlands through the Respondent bank's Agent/ Intermediary banks, namely, Standard Chartered Bank AG, Frankfurt and Deutsche Bank AG, Frankfurt ("the said TTs"):

(a) €48,800.00 (equivalent to RM236,192.00) on 24 March 2020;

(b) €20,400.00 (equivalent to RM98,736.00) on 24 March 2020;

and

(c) €51,900.00 (equivalent to RM249,639.00) on 26 March 2020

(collectively referred to as "the said Funds").

[21] She further submitted that on 30 March 2020, the Respondent Bank had received a call from the Appellant Customer's director, one Mr Palanivel with instructions to recall the said Funds. The said call on 30 March 2020 was attended to by DW-4 and it was proven that the Respondent Bank had immediately on that same date issued "MT S199 messages" to the Agent/ Intermediary Banks to recall the said Funds. The Respondent Bank received a formal letter from the Appellant Customer relating to the said TTs only on 31 March 2020.

[22] In trying to show that the Respondent Bank had done its best, it was submitted that the Respondent Bank had, through the Agent/Intermediary Banks, contacted ING Bank for further details and followed up, for months between 30 March 2020 and 3 June 2020, for the said Funds to be recalled. Even though only about 25% of the said Funds were refunded, learned counsel submitted that the Respondent Bank is entitled to disclaim liability to refund the balance.

[23] Learned counsel summed up that the Respondent Bank was informed by its Agent/Intermediary Banks that:

(a) in respect of the sum of €20,400.00, there were no funds available in the account with ING Bank, and ING Bank was not able to process the refund;

(b) in respect of the sum of €48,800.00, the Agent/Intermediary Banks had contacted ING Bank on several occasions, but no favourable reply was received from ING Bank; and

(c) ultimately, in respect of the sum of €51,900.00, ING Bank was able to refund the available balance of €31,826.75 (equivalent to RM150,063.13 as at 22 May 2020). The same was credited on 22 May 2020.

[24] Learned counsel for the Respondent Bank contended that the Sessions Court did not err in holding that clear and unambiguous terms that had been agreed by the Appellant Customer in the Remittance Form and therefore the Appellant Customer cannot hold the Respondent Bank liable or responsible for the Appellant Customer's loss, and that the transaction was done solely on the Appellant Customer's instructions and risk. Reference was made to cl 8 printed at the back of the Remittance Form and she submitted that "telegraphic transfers are sent entirely at the applicant's [the Appellant's] own risk and the Bank nor any of its branches, correspondents and agents shall be liable for any consequence." This is the main exclusion clause that the Respondent Bank relies on.

[25] She further submitted that the Respondent Bank does not have a duty of care to check and to give notice to and/or inform ING Bank to match the account number and name of the beneficiary/payee for telegraphic transfers.

[26] In her submissions, learned counsel for the Respondent Bank contended that the Appellant Customer's reliance on cl 9 of the terms and conditions of the Remittance Form is misplaced. She submitted that cl 9 specifically refers to Interbank Giro (IBG) transactions and not telegraphic transfers, as is the case herein. She also submitted that the Appellant had allegedly delayed in issuing "the recall instructions" and that "TT payments are known for their speed and typically go through in less than 5 to 10 minutes.

[27] In support of her submissions, learned counsel cited, inter alia, a High Court judgment in Koike (M) Sdn Bhd v. CIMB Bank Berhad [2018] MLRHU 1001, the English Court of Appeal's judgment in Tidal Energy Ltd v. Bank Of Scotland Plc [2015] All ER 15 and a judgment of the Court of Appeal in Public Bank Bhd & Anor v. Exporaya Sdn Bhd [2012] 6 MLRA 466 as authorities.

Judgment Of The Sessions Court

[28] The learned Sessions Court Judge agreed, almost wholly, with the submissions of learned counsel for the Respondent Bank, inter alia, that the terms and conditions in the Remittance Form, particularly the exclusion clause, are applicable to restrain the Appellant Customer from suing the Respondent Bank.

[29] The following passage in the Grounds of the learned Sessions Court Judge shows that he is of the view that the Appellant/Plaintiff has to sue the three strangers, whose accounts were credited with the said Funds that belong to the Appellant:

"[64] Selain itu, Plaintif telah gagal untuk mengambil sebarang tindakan terhadap penerima wang tersebut, iaitu, seorang Hr M Masseling, seorang Mw NR Suleman, dan seorang Hr A Nour yang butirannya telah didedahkan oleh ING Bank kepada Plaintif."

Analysis Of The Facts And Law

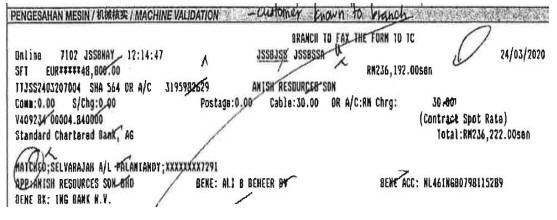

[30] First, I note that the name ALI B BEHEER BV which was recorded by the Respondent Bank as the name of the beneficiary/payee is as stated in the Remittance Form filled in by the Appellant Customer. This could be seen by the validation printed by the Respondent Bank on the Remittance Form submitted by the Appellant Customer, a screenshot of which is shown below:

[31] On the law applicable to the facts of this case, I find the facts in those authorities cited by learned counsel for the Respondent Bank are distinguishable from the present case. My analyses of those authorities are set out below.

[32] In Public Bank Berhad & Anor v. Exporaya Sdn Bhd [2012] 6 MLRA 466, the decision of the Court of Appeal is about the bank acting in good faith to guard against fraud, not applicable at all to this present case which is about a customer's money being erroneously credited into a stranger's account instead of into the account of the person named as the beneficiary/payee in the bank's Remittance Form.

[33] As for Koike (M) Sdn Bhd v. CIMB Bank Berhad [2018] MLRHU 1001, the facts are also distinguishable. In Koike (M) Sdn Bhd (supra), the customer had instructed a change in the beneficiary account number, which was duly complied with by the bank without a written confirmation. The customer sued the bank but the learned judge made a finding of fact in favour of the bank, as shown below:

"[23] In conclusion to the above, the Plaintiff's whole case is premised on technicality, ie the lack of a written confirmation from the Plaintiff on the change of the beneficiary account number. The Defendant, being a customer-oriented bank, sought only to aid in the effective and efficient transfer of the Plaintiff's monies to the beneficiary whom the Plaintiff intended to be Nissin Brake Vietnam Co Ltd holding account number 70111753200 with Banco Nacional de Mexico, It was only much later that the Plaintiff discovered that it had been defrauded and it was only at that stage that the Plaintiff, being desperate to recover its money, commenced this action against the Defendant alleging breach of contractual obligations and/or duty of care. The Defendant had acted strictly on the Plaintiff's instructions ie the change in the beneficiary account number and the Plaintiff was well aware of these instructions at all material times."

[34] Tidal Energy Ltd v. Bank Of Scotland Plc [2015] All ER 15 is an English Court of Appeal case. The customer (Tidal Energy Ltd) had applied for summary judgment but its application was dismissed at the High Court. On appeal, all three appellate judges delivered their respective judgments, with Floyd LJ writing the most thorough judgment.

[35] In Tidal Energy Ltd (supra), Lord Dyson disagreed with Floyd LJ primarily because the CHAPS System used in the United Kingdom (similar to IBG in Malaysia) requires very high speed for the remittance to be completed within 1.5 hours, and it is common knowledge that CHAPS is based primarily on the account number of the beneficiary/payee named by the remitter in the Transfer Form (a form similar to the Remittance Form in our present case).

[36] In other words, CHAPS in the UK is similar to IBG in Malaysia. This is relevant because the Respondent Bank in this case did expressly state in cl 9 of the terms and conditions printed at the back of the Remittance Form that IBG transactions are based solely on the beneficiary/payee's account number. However, nothing was mentioned about telegraphic transfer — the mode of remittance used in the present case. I shall discuss this point in detail below.

[37] The third judge in Tidal Energy Ltd (supra) was Tomlinson LJ. His Lordship was candid enough to admit that at the conclusion of the hearing, he actually shared the same thoughts expressed by Floyd LJ but subsequently decided to follow the Master of the Rolls, ie Lord Dyson. The result was a split decision, with Lord Dyson and Tomlinson LJ in the majority, and Floyd LJ dissenting with strong reasons. Tomlinson LJ did not fully agree with Lord Dyson's reasoning but ultimately followed Lord Dyson's conclusion; justifying it by ruling that by signing the Transfer Form, Tidal must be assumed to have agreed to all the terms of operation of CHAPS — which uses the receiving bank's name, sort code and beneficiary/payee's account number as identifiers, and which does not verify the name of the beneficiary/payee.

[38] For convenient reference, the relevant passages from the respective judgments of the three judges in Tidal Energy Ltd (supra) are set out below. I begin with excerpts from the judgment of Floyd LJ because, in my humble view, the reasonings in his judgment are most applicable to the facts of the appeal before me.

[39] In his judgment, Floyd LJ went through the various information to be stated by the customer in the Transfer Form and aptly described the information for identifying the beneficiary/payee as "identifiers". His Lordship pointed out 'Receiving (beneficiary) sort code', 'Receiving (beneficiary) bank and branch', 'Receiving (beneficiary) customer account number' and 'Receiving (beneficiary) customer name' as the 4 identifiers. The following are passages from the judgment of Floyd LJ:

"INTRODUCTION

[1] A customer gives its bank ('the remitting bank') instructions to pay one of its suppliers using the clearing houses automated payment system ('CHAPS'). The instructions include the correct name of the supplier whom the customer wishes to pay. However, the instructions also include numerical data (account number and sort code) which the customer believes, wrongly, to be the bank account of the supplier at another bank ('the receiving bank'). In fact, although there is an account corresponding to those numerical data at the receiving bank, it is in the name of, and belongs to, a third party, apparently unconnected with the supplier or the customer. The receiving bank does not check the name on the account to confirm that it corresponds to the name of the supplier, because it is not banking practice to do so. Once the amount of the transfer is credited to the third party's account, it is withdrawn. Is the remitting bank entitled in the circumstances to debit the customer's account with the amount transferred? That is the issue which arises on this appeal.."

"[5] The transfer form was headed 'Your request to make a CHAPS transfer'. In s 1 the form required the customer to insert what it described as 'Details of the CHAPS transfer'. It informed the customer that all requests received by 3pm will normally be made on the same business day. Section 1 of the transfer form contained a series of boxes in which the customer must fill in details of the transfer. These included the date that the transfer was to be processed, the amount of the transfer in figures and in words, and further boxes entitled 'Sending (remitter) sort code', 'Sending (remitter) account number', 'Account number to be charged (if different)', 'Sending (remitter) name', 'Payment reference (if known)', and 'Payment details (if any)'. Tidal provided the relevant mandatory details, and gave its supplier's invoice number in the optional 'payment details (if any)' box.

[6] There followed four boxes, still within s 1 of the transfer form, giving details of the destination of the transfer. These boxes were entitled 'Receiving (beneficiary) sort code', 'Receiving (beneficiary) bank and branch', 'Receiving (beneficiary) customer account number' and 'Receiving (beneficiary) customer name'. Tidal filled in the first three of these boxes with the banking information with which it had been supplied, purportedly by Design Craft. These identified the receiving (beneficiary) bank as Barclays (but did not specify a branch). In the fourth box Tidal inserted the name of the intended recipient of its funds, namely Design Craft Ltd.

[34] To my mind, on the proper construction of this form, a payment cannot be said to be made until funds are credited into an account which conforms to the four identifiers which the customer is required to give in s 1 of the form: sort code, bank name, account number and customer name. It seems to me to be plain, as I think it did to the judge, that the first three of these are essential indicators of when a payment has been made. I can see no rational criterion for excluding the fourth identifier — customer name. Indeed, so far as the customer is concerned at least, it could be said to be the most important. The judge expressly found that the identity of the beneficiary was important to Tidal and noted that the customer could be forgiven if he thought that the account name mattered, given that the transfer form included a box for naming the beneficiary and mentions the 'payee'. If that is the case, then the reaction of the reasonable person to the language used in the form is the same. There is nothing whatever in the form, or the admissible background, to alert the reasonable person to the fact that, in routing the payment, account would be taken of some but not all of the identifiers, and in particular that no account would be taken of the name. Tidal was of course consenting to the use of the CHAPS system (or indeed any other payment method which the bank decided on) to carry out its instructions, but Tidal was not agreeing that the bank could carry out those instructions in a way which allowed it to disregard any of the identifiers, least of all the name of the beneficiary.

[35]... It is, however, entirely reasonable for a customer to expect the bank to obtain an acknowledgement that a credit has been made to an account conforming to all (and not just some) of the identifiers given on the transfer form, when he is given nothing to make him believe the contrary.

[36] It follows that on the construction of the form which I consider to be correct, the bank has no right to debit the customer's account when a transfer is made to an account having the correct sort code and account number but a different account name. The customer has the right to prevent the bank from debiting his account except when the payment is made to an account matching the four identifiers. Nothing in the private arrangements between the banks as to how they manage CHAPS payments between themselves, such as their decision to disregard the beneficiary's name, can add to or derogate from that right.

[37] Lurking beneath the submissions in this case is a suggestion that, if we were to decide the case against the bank, it would undermine the CHAPS system. I cannot accept that this is so for a number of reasons. Firstly, the bank could deal with the matter by drawing attention to the relevant aspect of the system on their CHAPS transfer forms, or when they accept oral instructions, if they do, to make a CHAPS transfer. In those circumstances it would be clear that a 'payment' in accordance with the instruction would be made provided only that the sort code, bank and account number coincided with those on the form. If, for commercial reasons, they prefer not to take this simple step, then the risk that there will be a percentage of transfers for which a customer may subsequently claim to be reimbursed is a risk which the bank voluntarily undertakes. In that connection there was some material before the judge that the banks did at one time operate a process of manual checking when a CHAPS transfer exceeded £50,000.00. The abandonment of the manual checking process was no doubt based on an assessment of the risk which the bank was prepared to take.

[38] Although this is an appeal from a summary judgment, neither side suggested that it turned on the test for summary judgment. The bank expressly accepted that if the instruction was an instruction to pay Design Craft rather than Barclays, then it would have no defence. In my judgment it is clear that the bank only had authority to debit Tidal's account if a payment was made which complied with the four identifiers on the transfer form. I would, for my part, have allowed the appeal and granted summary judgment to Tidal on its claim.

[40] As mentioned in para [35] above, Lord Dyson's main ground in Tidal (supra) was that all parties agreed that very high speed is required for the remittance to be performed under the CHAPS System used in the United Kingdom (similar to IBG in Malaysia), to complete the remittance within 1.5 hours, and it is common knowledge that CHAPS is based primarily on the account number of the beneficiary/payee named by the remitter in the Transfer Form (a form similar to the Remittance Form in our present case).

[41] I have considered the 'necessity for speed' argument submitted by learned counsel for the Respondent Bank whereby she seeks to rely on the majority judgment in Tidal Energy Ltd (supra). My answer to that point is in the following paragraphs.

[42] Upon a thorough reading of the judgments of Floyd LJ (dissenting), Tomlinson LJ and Lord Dyson (majority), I find the facts highlighted by the majority judges in Tidal Energy Ltd (supra) are distinguishable from the present case. First, the remittance system in Tidal Energy Ltd (supra) known as CHAPS is based solely on the beneficiary/payee's account number for the purpose of achieving speedy completion of the remittance. The maximum period under CHAPS is within 1.5 hours, meaning that any remittance completed after 1.5 hours have elapsed, would be considered a delayed transaction.

[43] The high-speed feature of CHAPS was accentuated by Lord Dyson in Tidal Energy Ltd (supra) in the following passage of his judgment as his main ground for deciding in favour of the bank:

"[62] In my judgment, the construction sought by the appellant produces a result which is not reasonable and not commercially sensible (and therefore unlikely to have been intended by the parties) for the following reasons. First, the object of the CHAPS system is to achieve rapid (maximum of 1.5 hours) payment. That is why customers choose to use this system of electronic payment. Secondly, the court should lean against a construction which involves imposing a requirement on a receiving bank which would frustrate the customer's wish to have the money transferred within 1.5 hours."

[44] As a matter of fact, the CHAPS system used in the United Kingdom is comparable to the IBG system in Malaysia which uses a beneficiary/payee's account number as the sole identifier for remittance purposes — and which the Respondent Bank deemed fit to make it an express condition — in cl 9 of the terms and conditions printed at the back of the Remittance Form. Clause 9 at the back of the Respondent Bank's Remittance Form states:

"9. For IBG transactions, the credit to the beneficiary's account will be based solely on the account number given by the applicant."

[45] Now, what would be a fair and reasonable interpretation of the said cl 9? In my view, since the Respondent Bank had drafted it to state that only IBG transactions shall be based solely on one identifier, ie the account number of the beneficiary/payee stated in the Remittance Form, it would be fair, reasonable and logical to construe cl 9 as intended to mean that remittance transactions, other than IBG ones, would still be transacted based on other identifiers that the Appellant Customer had to fill in the Remittance Form, including the name of the beneficiary/payee, to be used to identify the beneficiary/payee's bank account. In the Remittance Form, there is no clause similar to cl 9 regarding telegraphic transfer of money.

[46] Even though learned counsel for the Appellant Customer did not mention the principle of construction of contractual terms known in Latin as "Expressio Unius Est Exclusio Alterius", I find that his submissions on cl 9 were along the same line. A literal translation of Expressio Unius Est Exclusio Alterius is "The Expression of One Is the Exclusion of Another". When this trite common law principle is applied to the aforesaid cl 9, it means that when an item (IBG transaction in this case) is expressly stated in the terms and conditions, other items of the same class (other modes of remittance) which are omitted from those terms and conditions are presumed to have been intentionally omitted.

[47] Had the Respondent Bank intended to make it a condition for all transactions, including telegraphic transfers, to be based solely on the account number of the beneficiary/payee, it could easily have stated just that in cl 9, instead of mentioning only IBG transactions in cl 9. Thus, it is my judgment that the application of the principle of Expressio Unius Est Exclusio Alterius leads to a fair and reasonable interpretation of cl 9 in favour of the Appellant Customer: that the Respondent Bank agreed to perform the remittances based on the name of the beneficiary/payee as an identifier as well as the beneficiary/payee's account number.

[48] It is beyond dispute that bank customers worldwide are identified by their names and not account numbers — especially after the coming into force of international anti-money laundering laws. This point fortifies my finding that unless the Respondent Bank stipulates clearly that telegraphic transfers of its customers' funds shall be based solely on the beneficiary/payee's account number, the beneficiary/payee's name must be deemed to be a mandatory identifier besides the beneficiary/payee's account number. The contra proferentem rule would also result in an interpretation against the Respondent Bank because the terms and conditions in the Remittance Form were imposed by the Respondent Bank on its customers.

[49] There are probably more ways than one for the Respondent Bank to ensure that the name of the beneficiary/payee as well as his account number are used by the receiving bank as identifiers. A simple and direct approach could be, for the purpose of fulfilling its contract with the Appellant Customer, to make it a condition for its Agent/Intermediary banks to stipulate a term that besides the account number, the receiving bank (ING Bank in this case) must regard the name of the beneficiary/payee as a mandatory identifier. This was obviously not done. Had this been done by the Respondent Bank, in all probability it would have resulted in ING Bank suspending the said Funds when it found that those three account numbers were not in the name of ALI B BEHEER BV, and reverting to the Respondent Bank through the Agent/Intermediary banks with a query.

[50] En passant, I would also point out that Lord Dyson in Tidal Energy Ltd (supra) did express his agreement with the dissenting judge (Floyd LJ) that the remitting bank could have made it clear that the remittance shall be based on the sort code, name of the bank where the beneficiary/payee's account is maintained and the account number, ie expressly excluding the beneficiary's name as an identifier. As discussed above, the Respondent had, in the said cl 9, chosen to make this condition applicable to only IBG transactions, and not to telegraphic transfers as in this case. The words of Lord Dyson on this point are as follows:

"[64] Floyd LJ says that the remitting bank could make it clear on the form that a 'payment' in accordance with the instruction will be made provided only that the sort code, bank and account number (but not the name) coincides with those on the form. I accept that this could be done."

[51] The words of Floyd LJ in Tidal (supra) ring loud and clear for the present appeal before this Court to be allowed because cl 9 of the Remittance Form states that only IBG transactions shall be based solely on the account number of the beneficiary/payee. Floyd LJ opined:

"There is nothing whatever in the form, or the admissible background, to alert the reasonable person to the fact that, in routing the payment, account would be taken of some but not all of the identifiers, and in particular that no account would be taken of the name."

[52] As Floyd LJ pointed out, the identity of the beneficiary/payee is important as the Transfer Form (in Tidal (supra)) included a box for naming the beneficiary/payee. The Respondent Bank might as well have done without this box in the Remittance Form if the name of the beneficiary/payee is irrelevant and to be disregarded as an identifier for remittance purposes.

[53] The alleged delay submitted by learned counsel made no difference because if, as submitted by learned counsel for the Respondent Bank, remittances by telegraphic transfers "are known for its speed and typically go through in less than 5 to 10 minutes", the money would still have gone into the wrong account even if a recall had been requested on 27 March 2020. The material issue is, as discussed above, whether the Respondent Bank ought to have instructed its Agent/Intermediary Banks to ensure that the remitted funds are credited into a bank account in the name of the beneficiary named in the Remittance Form with the account number as stated therein. Telegraphic transfers overseas are commonly known to take several working days. There was no condition or urgency for the remittance in the present appeal before me to achieve "rapid (maximum of 1.5 hours) payment" (to borrow the words of Lord Dyson in describing the CHAPS system used in the UK).

[54] I reiterate the point that the name of the beneficiary/payee "ALI B BEHEER BV" was validated by the Respondent Bank (see screenshot shown in para [30] above). Thus, it is my judgment that the name of the beneficiary/ payee "ALI B BEHEER BV", stated in the Remittance Form and validated by the Respondent Bank, was an identifier that it ought to have stipulated when instructing its Intermediary/Agent banks. The Respondent Bank's failure to do so had resulted in a breach of contract and losses suffered by the Appellant. Therefore, the Respondent Bank ought to be held liable to repay the said Funds to the Appellant Customer.

[55] The final issue is whether the exclusion clause imposed by the Respondent Bank, in cl 8 of the Remittance Form, is valid or void.

[56] Based on the Federal Court's judgment in CIMB Bank Berhad v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke & Anor [2019] 1 MLRA 599, I decided that s 29 of the Contracts Act 1950 is applicable to invalidate the exclusion clause relied on by the Respondent Bank in this appeal. Section 29 reads:

"Every agreement, by which any party thereto is restricted absolutely from enforcing his rights under or in respect of any contract, by the usual legal proceedings in the ordinary tribunals, or which limits the time within which he may thus enforce his rights, is void to that extent."

[57] CIMB Bank Bhd v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke (supra) is a judgment of the Federal Court that is binding on this Court. The facts and chronology of events in CIMB Bank Bhd v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke (supra) were succinctly summarised in the law journal, as follows:

"The respondents took a loan from the appellant to buy a property in Malaysia. As the property was still under construction, the appellant was contractually bound to make progressive payments to the developer as per the stage of completion of the construction on receiving an invoice to that effect from the developer. The appellant failed to make one such progress payment for about a year causing the developer to terminate its sale and purchase agreement ('SPA') with the respondents. The respondents sued the appellant for general, special, exemplary and/or aggravated damages for breach of contract and/or negligence and breach of fiduciary duty. The High Court dismissed the claim on the ground that cl 12 of the loan agreement absolved the appellant of any liability. Essentially, cl 12 provided that the appellant would not be liable to pay the respondents for any 'loss of income or profit or savings, or any indirect, incidental, consequential, exemplary, punitive or special damages' that they might incur. On the respondents' appeal, the Court of Appeal ('COA') set aside the High Court's decision and held that: (a) the appellant had breached a fundamental term of the loan agreement in failing to pay the progress payment and had also breached its duty of care to the respondents by causing the SPA to be terminated and the respondents to suffer loss and damage; and (b) since cl 12 effectively barred the respondents from initiating any form of legal proceedings to enforce their rights, it was void under s 29 of the Contracts Act 1950 ('the CA'). The appellant was granted leave to file the instant appeal against the COA's decision on the question whether s 29 of the CA could invalidate an exclusion clause which not only exonerated a contract-breaker of liability for breach of contract but also of liability to pay compensation for failing to perform the contract. At the appeal hearing, the appellant argued that the parties had agreed to include cl 12 in the loan agreement and that since cl 12 did not expressly prohibit the respondents from filing any legal proceedings nor did it oust the jurisdiction of the court, it did not offend s 29 of the CA. The respondents, on the other hand, submitted that by barring the recovery of any form of damages, cl 12 effectively rendered futile any legal action by the respondents against the appellant for breach of the loan agreement. The respondents also said cl 12 should be held invalid for offending public policy as it absolved the appellant of any liability even if it was wholly responsible for breaking the contract."

[58] The Federal Court in CIMB Bank Bhd v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke (supra) decided in favour of the customer and dismissed the bank's appeal. In essence, the Federal Court held that the exclusion clause (referred to as "Clause 12" in that case) imposed by the bank contravened s 29 of the Contracts Act 1950, and is therefore void. Since the point in issue is comparable, the doctrine of stare decisis is unequivocal in requiring this Court to adhere to the precedent set by the Federal Court. The reasonings of the Federal Court are enunciated in the following passages of the judgment of Balia Yusof FCJ (as he then was):

"[64] In Merong Mahawangsa Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Dato' Shazryl Eskay Abdullah [2015] 5 MLRA 377 at p 365, this court had observed:

[42] It should also be said that public policy is not static. 'The question of whether a particular agreement is contrary to public policy is a question of law... It has been indicated that new heads of public policy will not be invented by the courts for the following reasons... However, the application of any particular ground of public policy may vary from time to time and the courts will not shrink from properly applying the principle of an existing ground to any new case that may arise... The rule remains, but its application varies with the principles which for the time being guide public opinion' (Halsbury's Laws of England (5th Ed, Vol 22) at para 430).

[65] Clause 12 may typically be found in most banking agreements. In reality, the bargaining powers of the parties to that agreement are different and never equal. The parties seldom deal on equal terms. In today's commercial world, the reality is that if a customer wishes to buy a product or obtain services, he has to accept the terms and condition of a standard contract prepared by the other party. The plaintiffs, as borrowers in the instant case, are no different. They have unequal bargaining powers with the defendant. As succinctly put by Lord Reid in the House of Lords in Suisse Atlantique Societe D'armement Maritime SA v. NVRotterdamsche Kolen Centrale [1966] 2 All ER 61:

Exemption clauses differ greatly in many respects. Probably the most objectionable are found in the complex conditions which are not so common. In the ordinary way the customer has no time to read them, and if he did read them he would probably not understand them. And if he did understand and object to any of them, he would generally be told he could take it or leave it. And if he then went to another supplier the result would be the same. Freedom of contract must surely imply some choice or room for bargaining.

[66] In our considered view, this is one instance which merits the application of this principle of public policy. There is the patent unfairness and injustice to the plaintiffs had this cl 12 been allowed to deny their claim/rights against the defendant. It is unconscionable on the part of the bank to seek refuge behind the clause and an abuse of the freedom of contract. As stated by Denning LJ in John Lee & Son (Grantham) Ltd And Others v. Railway Executive [1949] 2 All ER 581:

Above all, there is the vigilance of the common law while allowing for freedom of contract, watches to see that it is not abused."

[59] Reverting back to the exclusion clauses in the present appeal, the main one is cl 8, printed at the back of the Remittance Form and it restrains the Appellant Customer's rights to sue the Respondent Bank for the loss which the Appellant Customer had suffered in this case. The material parts read:

"Telegraphic transfer (TT)... are sent... entirely at the applicant's [customer's] own risk. Neither the Bank nor any of its branches, correspondents and agents shall be liable for any consequence which may arise through interruption, omission, error, misinterpretation, mutilation, loss or delay in transmission". An enlarged screenshot of the full cl 8 is shown below:

8. Telegraphic Transfer (TT) and Interbank Giro (IBG) are sent by wire, cable or telex or through any other channels, coded as required, entirely at applicant's own risk. Neither the Bank nor any of its branches, correspondents and agents shall be liable for any consequence which may arise through interruption, omission, error, misinterpretation, mutilation, loss or delay in transmission.

[60] I would respectfully refer to the risks posed by the Respondent Bank's exclusion clause as "veiled risks" because cl 8 is printed in such tiny fonts that an elderly customer would certainly need magnifying glasses to read it. The said exclusion clause fits the proverbial description of "small print" — intended to surface as a shield against the bank's customers whenever a cause of action arises against the bank, such as in this case. In my judgment, this is precisely the type of case when the courts ought to invoke s 29 of the Contracts Act 1950 to invalidate the inequitable exclusion clause shrouded in small print at the back of the Remittance Form. As mentioned above, I stand guided by the judgment of the Federal Court in CIMB Bank Bhd v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke (supra).

Conclusion

[61] In conclusion, I reiterate that in the absence of a term stating that the remittance shall be performed solely by relying on the account number of the beneficiary/payee, the Respondent Bank is legally obliged to stipulate the name of the beneficiary/payee as an identifier when instructing its Agent/ Intermediary banks to complete the remittance. As for the exclusion clauses cited by the Respondent Bank, I rule that it is unconscionable for the bank to seek refuge behind exclusion clauses that leave the Appellant Customer in a lurch — literally telling the customer to go to the Netherlands to sue strangers who were not named in the Remittance Form. Those clauses printed at the back of the said Form, in particular cl 8, which have the effect of restricting the rights of the Appellant Customer to sue the Respondent Bank, are void. As mentioned above, I am following the decision of the Federal Court in CIMB Bank Bhd v. Anthony Lawrence Bourke (supra).

[62] By reason of the above facts and law, I decided that this Court ought to allow the Appellant's appeal with costs. The Respondent Bank must repay the balance sum of RM434,503.87 to the Appellant.