Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Lee Swee Seng, Azhahari Kamal Ramli, Wan Ahmad Farid Wan Salleh JJCA

[Civil Appeal Nos: W-01(A)-473-08-2021, W-01(A)-477-08-2021 & W-01(A)-478-08-2021]

3 January 2025

Contract: Employment contract — Breach — Transfer of employees (appellants) who refused to take up offer of employment by entity that acquired Company's branches following corporate restructuring exercise — Whether transfer exercise mala fide, went to root of appellants' contracts of employment and a fundamental breach — Test for constructive dismissal — Whether 'contract test' or 'reasonableness test' applicable — Whether constructive dismissal established

Employment: Unfair dismissal — Constructive dismissal — Transfer of employees (appellants) who refused to take up offer of employment by entity that acquired Company's branches following corporate restructuring exercise — Whether transfer exercise mala fide, went to root of appellants' contracts of employment and a fundamental breach — Test for constructive dismissal — Whether 'contract test' or 'reasonableness test' applicable — Whether constructive dismissal established

Labour Law: Employment — Constructive dismissal — Transfer of employees (appellants) who refused to take up offer of employment by entity that acquired Company's branches following corporate restructuring exercise — Whether transfer exercise mala fide, went to root of appellants' contracts of employment and a fundamental breach — Test for constructive dismissal — Whether 'contract test' or 'reasonableness test' should be applied — Whether constructive dismissal established

The appellants in the instant appeals were the employees of Perodua Sales Sdn Bhd ('Company'), one of whom was a mechanic and the other two were service advisors, who had served between 9 and 22 years with the Company. By way of an internal memo dated 24 August 2017, the Company informed the appellants and 20 other employees at its Bukit Beruntung branch and Sungai Choh service centre that its business operations thereat had been taken over by one Nagoya Automobile Malaysia ('NAM') following a corporate restructuring exercise, and that they should take up the employment offer made by NAM where they would be engaged for a fixed term of 2 years but they would first be required to tender their resignation from the Company. When the 2-year term with NAM was over, NAM would have the sole discretion whether to retain them and if not, they would have to reapply to the Company and it would then decide whether the employees would be taken back depending on the availability of vacancies and the needs of the Company. The employees' years of service with the Company however, were not recognised in the 2-year contract with NAM. The appellants resisted the move which subjected their permanent position to a 2-year fixed-term contract with no certainty of being retained by NAM or re-employed by the Company, and there was silence as to what would happen to their years of service with the Company. The Company then issued a notice of transfer to the appellants requiring each of them to respectively report for work within 3 days, in Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu. The Company refused to consider the appellants' appeal against the transfer and issued a show cause notice for insubordination to the appellants for failing to obey its allegedly valid and reasonable orders and for being absent from work for 2 or more continuous days when they did not report to work at their new postings. The appellants considered themselves as having been constructively dismissed and commenced proceedings in the Industrial Court. The Industrial Court found that the Company's conduct went to the root of the appellants' contracts of employment and evinced an intention not to be bound by the same, that the transfer exercise was not done bona fide and was unreasonable in the circumstances and would bring financial ruin to the appellants as well as cause physical and emotional hardship. The Industrial Court accordingly held that the constructive dismissal was proven and awarded the appellants compensation in lieu of reinstatement and back wages based on their last drawn salaries and years of service. The High Court upon judicial review, held that it was not proven that the transfer was effected in breach of the appellants' contracts of employment, that the transfer was part and parcel of the Company's exercise of managerial prerogative and that the 'transfer' clause in the contracts of employment entitled the Company to require its employees to perform their services at such other locations in Malaysia as reasonably required by it. The High Court further held that the Industrial Court was wrong in applying the 'reasonableness test' instead of the 'contract test' as the test for constructive dismissal, and had erred in law and fact in finding that the Company had forgotten the necessity for applying for work permits for the appellants when the issue of work permit was not pleaded. Hence the instant appeals.

Held (allowing the appeals):

(1) The test for constructive dismissal as was clarified and confirmed in Tan Lay Peng v. RHB Bank Berhad & Anor, was the 'contract test' and not the 'reasonableness test'. However, in analysing and assessing if the conduct of the Company and the circumstances of the case justified the transfer as being reasonable or otherwise, the context that triggered the transfer must be examined as a whole. That examination did not convert the 'contract test' into the 'reasonableness test'. It was very much a 'contract test' with the requirement of 'reasonableness' built into it as part of the contractual term on 'transfer' that the Company had agreed with its employees. (paras 25 & 35)

(2) The approach taken by the Industrial Court was mistakenly interpreted by the High Court to be a 'reasonableness test' approach. Instead, the Industrial Court had applied the 'contract test' and taken into consideration the agreed requirement of 'reasonableness' as a term of the contracts of employment, and had not erred in doing so. (paras 41-42)

(3) It was unreasonable in the circumstances for the Company to have insisted that the employees resign from their employment before taking up the offer of employment by NAM for a 2-year term, and required the appellants to report to their new work stations in far-flung locations three days after issuing the notice of transfer. The Company's action was a manifestation of its intention not to be bound by the terms of the appellants' contracts of employment. (paras 56, 61 & 62)

(4) On the facts, the transfer exercise was mala fide when tested against the requirement of reasonableness which the parties had agreed as part of the terms of the contract. The Company's action went to the root of the contract and was a fundamental breach. In the circumstances, the appellants were right in treating themselves as having been constructively dismissed. Both the manner and motive of the transfer exercise did not pass the contract test of reasonableness as promised by the Company in their contracts of employment. (paras 71, 72 & 89)

(5) Although the issue of lack of a work permit or employment pass of two of the appellants was not pleaded, the Court or Tribunal must take cognisance of the same when the issue was raised as it was illegal for the Company to require its employees to start work without a valid work permit or employment pass. This was a breach of the immigration laws of Sabah and Sarawak by the Company which would go to the root of the contract and its action in citing the two appellants for misconduct in not reporting to work was unreasonable in the circumstances of the case. Hence, the two appellants were entitled to treat themselves as being constructively dismissed. (paras 95 & 99)

(6) The Industrial Court had not erred in concluding that constructive dismissal was proven in this case and had taken into consideration all the relevant factors after having appreciated that the requirement of 'reasonableness' was a term in the contract where the transfer exercise was concerned.The Court was satisfied that the Industrial Court had acted according to equity, good conscience and the substantial merits of the case without regard to technicalities and legal form as mandated under s 30(5) of the Industrial Relations Act 1967. (paras 113-114)

Case(s) referred to:

Airspace Management Services Sdn Bhd v. Col (B) Harbans Singh Chingar Singh [2000] 1 MLRA 664 (refd)

Barat Estates Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Parawakan Subramanian & Ors [2000] 1 MLRA 404 (refd)

Merong Mahawangsa Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Dato' Shazryl Eskay Abdullah [2015] 5MLRA 377 (refd)

Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan Bhd v. Transport Workers Union [1995] 1 MLRA 268 (folld)

Tan Lay Peng v. RHB Bank Berhad & Anor [2024] 5 MLRA 171; [2025] 1 MELR 699 (folld)

Western Excavating (ECC) Ltd v. Sharp [1978] IRLR 27 (refd)

Wong Chee Hong v. Cathay Organisation Malaysia Sdn Bhd [1987] 1 MELR 32; [1987] 1 MLRA 346 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Evidence Act 1950, s 106

Federal Constitution, art 6

Immigration Act 1959/63, s 66

Immigration Regulations 1963, regs 5, 16, 39

Industrial Relations Act 1967, ss 20, 30(5)

Labour Ordinance (Sabah) (Cap 67), ss 118, 130L

Labour Ordinance (Sarawak) (Cap76), ss 119, 130L

Counsel:

For the appellants: Mohan Ramakrishnan; M/s Ramakrishnan & Associates

For the 1st respondent: Shariffullah Majeed (Chong Yue Han & Nurul Aisyah Hassan with him); M/s Lee Hishammuddin Allen & Gledhill

JUDGMENT

Lee Swee Seng JCA:

[1] Three employees of Perodua Sales Sdn Bhd ("Perodua/the Company") found themselves in a quandary. They had all served between 9 and 22 years with the Company, one being employed as a mechanic and the other two as service advisors. Together with some 20 other employees in Perodua's Branch in Bukit Beruntung and its Sales Service Centre in Sungai Choh, Rawang, they were each given a letter explaining that one Nagoya Automobile Malaysia ("NAM") had taken over Perodua's business operations at Bukit Beruntung and Sungai Choh. The letter further stated that they should take up the employment offer made by NAM.

[2] Like most contracts and correspondences, the devil is in the details. Upon closer scrutiny of the relevant documents, it became apparent that all employees taking up the offer would be engaged for a fixed term of 2 years and they would first be required to tender their resignation from Perodua. After the 2-year term with NAM is over, NAM would have the sole discretion whether to retain them and if not, it would appear that they would have to reapply to Perodua and the Company would then decide whether they would be taken back as that decision would depend on availability of vacancies and the needs of Perodua then.

[3] The 3 employees felt that it was a raw deal as what was to them a permanent position is now being subject to a 2-year fixed term contract with NAM with no certainty of being retained by NAM nor re-employed by Perodua and there was also a deafening silence on what would happen to the years of service that they had each put into the Company Perodua.

[4] There were various rounds of meetings between Perodua and the employees affected by this corporate restructuring exercise involving the transfer of business in these 2 branches to NAM. Perodua obviously would want all the employees to take up the offer from NAM as it would release Perodua from any further contractual obligations to its employees. However, the 3 employees resisted the move for what they perceived to be their legal rights to choose to remain with Perodua for any offer of employment in a business takeover should be on terms no less favourable.

[5] They were not prepared for the next move by Perodua which was a Notice of Transfer dated 27 September 2017, requiring them to report for work within 3 days: one to Kota Kinabalu, another to Kuching and yet another to Kuala Terengganu. They pleaded with Perodua respectively in their letters of 28 September 2017 to reconsider the transfer to these faraway places and to appeal for a transfer to some other branches nearby but to no avail. The Company issued them a show cause notice dated 9 October 2017 of insubordination for failing to obey valid and reasonable orders of the Company and for being absent for work for 2 or more continuous days when they did not report to work at their new postings. They in turn implored the Company to reconsider its position after reiterating why the transfer would be unreasonable and when there was no reply from the Company, they treated themselves to have been constructively dismissed as at 24 October 2017 and referred the matter to the Director General of Industrial Relations under s 20 of the Industrial Relations Act 1967 ("IRA").

Before The Industrial Court

[6] The Industrial Court handed down its Award for each of the 3 employees as Claimants in their reference for dismissal without just cause and excuse and held that the conduct of the Company Perodua went to the root of the contract and evinced an intention not to be bound by the contract of employment entered into with the affected 3 employees. It was also held that the transfer exercise was not reasonable, as the Company have introduced this element of "as reasonably directed by the Company" into the "Transfer" clause in its contract with one of the 3 employees who joined later.

[7] The Industrial Court discerned this change in approach in exercising its managerial prerogative of transfer as importing into this contract a more humane approach to transferability, taking into consideration all relevant factors that may operate within the meaning of "as reasonably directed by the Company" where location of transfer is concerned.

[8] The Industrial Court held that the exercise by the Company of transfers to these 3 faraway locations were not done bona fide and were unreasonable in the circumstances of the case where additional costs monthly would have to be incurred by these affected employees who have their commitments here to attend to. They have their spouse, schoolgoing children and in one case an aged mother to care for. With a young growing family, each would have to face with disruptive changes to adapt, especially when no additional allowances were provided for such outstation and East Malaysian transfers beyond the one-off hotel accommodation, transportation, disturbance allowance and insurance coverage.

[9] The Industrial Court further held that such a transfer would bring financial ruin to the Claimants and cause physical and emotional hardship. With the same salary and the additional costs in setting up a home or even living singly if the family is left behind, would cause financial hardship without even factoring in the airfare travel back to see the family − so much for work-life balance that companies with a heart are to promote.

[10] The Industrial Court found no indication in the relevant correspondence encouraging the employees to accept NAM's 2-year contract of the assurance that their accumulated years of service and seniority would be considered upon the contract's expiration or in the event of its early termination. What is even more uncertain is that the employee must reapply to join back Perodua should NAM not require their services anymore and the decision to take them back would be on a case-by-case basis.

[11] Against the above context culminating in the Notice of Transfer, the Industrial Court held that the conduct of the Company in such manoeuvres clearly demonstrated its intention not to be bound by the contract of employment, going to the root of the contract.

[12] The Industrial Court found that the Claimants had proved constructive dismissal against the Company and awarded the usual compensation in lieu of reinstatement and backwages based on their last drawn salaries and the years of service with the Company.

At The High Court

[13] The High Court held that the transfer was part and parcel of the exercise of managerial prerogative of the Company and for so long as it was not done mala fide, the Industrial Court should not interfere with it. The High Court further held that the Contract of Employment with each of the employees contained a cl 8 on "Transfer" where the Company has the right to require the employee to perform his services at such other location, elsewhere in Malaysia as reasonably directed by the Company.

[14] The High Court held that the Company had adhered to the terms of the contract and had not evinced its intention to no longer be bound by it. The High Court further held that the Industrial Court had applied the wrong test for constructive dismissal by applying the "reasonableness test" and not the "contract test".

[15] The High Court also found that the Industrial Court had erred in law and fact when it found that "in this haste the Company even forgot the necessary application of work permit for the Claimant" when there was no record of that in the notes of proceedings before the Industrial Court. (See para 42 of the High Court's judgment and para 35 of the Award.) The High Court further noted that the issue of work permit was not pleaded to allow the Company to rebut the same and that parties are bound by their pleadings.

[16] The High Court concluded that the Claimants had failed to prove that Perodua, in transferring the employees to the different locations in Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu, was in breach of a fundamental term of the contracts of employment or that it had evinced an intention not to be bound by it.

[17] The High Court quashed the Awards of the Industrial Court for each of the 3 employees and allowed the appeals of the Company. Against the decision of the High Court, the Claimants had appealed to the Court of Appeal.

Before The Court of Appeal

[18] The grounds of appeal and the issues canvassed before us may be summarised as follows:

(i) Whether the "Transfer" clause that refers to the employee having to perform his services in the current location or "in such other locations as reasonably directed by the Company" would subject the transfer exercise to the "reasonableness test" as part of the "contract test" that parties have agreed;

(ii) Whether in the context of the events triggering the Notice of Transfer and the conduct of the Company, the transfer exercise was mala fide and manifested the intention of the Company not to be bound by the Contract;

(iii) Whether having regard to the circumstances of each of the employees, the transfer exercise was mala fide for a collateral purpose;

(iv) Whether the Industrial Court and the High Court may take notice of illegality once it is raised and led in evidence with respect to the absence of a valid work permit for the purpose of reporting to work in Kota Kinabalu and Kuching;

(v) Whether the Claimants had discharged their legal burden of proving constructive dismissal in the light of the evidential burden of the Company to show that the only vacancies available were in Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu.

[19] The Claimants were the Appellants before the Court of Appeal and where the context requires, they shall be referred by their names and the Company Perodua was the 1st respondent and the Industrial Court being the nominal 2nd respondent.

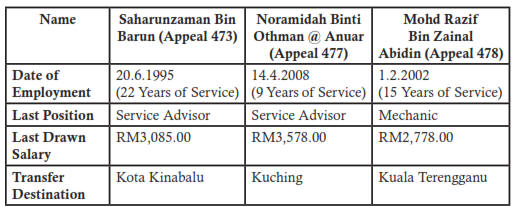

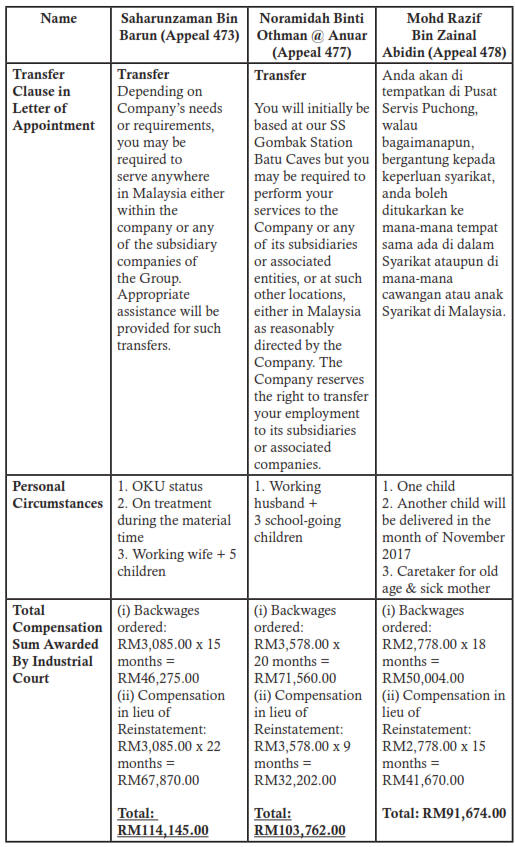

[20] Civil Appeal No. W-01(A)-473-08/2021 ("Appeal 473") is that of Saharunzaman Bin Barun ("Saharunzaman"). Civil Appeal No. W-01(A)477-08/2021 ("Appeal 477") is that of Noramidah Binti Othman @ Anuar("Noramidah") and lastly Civil Appeal No. W-01(A)-478-08/2021 ("Appeal 478") is that of Mohd Razif bin Zainal Abidin ("Razif").

[21] For brevity where the documents referred to are substantially the same, only one reference would be made and it is with respect to the Enclosures in Appeal 473 that of Saharunzaman.

[22] The key facts of each of the Claimants/Appellants are tabulated in the table below for ease of reference and comparison:

[23] We accept as the correct position of the law as regards the test to issue an order to quash or set aside an Award of Industrial Court as that held by the Court of Appeal in Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan Bhd v. Transport Workers Union [1995] 1 MLRA 268 at 282-283 as follows:

"An inferior tribunal or other decision-making authority, whether exercising a quasi-judicial function or purely an administrative function has no jurisdiction to commit an error of law. Henceforth, it is no longer of concern whether the error of law is jurisdictional or not. If an inferior tribunal or other public decision maker does make such an error, then he exceeds his jurisdiction. So too, is jurisdiction exceeded where resort is had to an unfair procedure (see Raja Abdul Malek Muzaffar Shah Raja Shahruzzaman v. Setiausaha Suruhanjaya Pasukan Polis & Ors [1995] 1 MLRA 57, or where the decision reached is unreasonable, in the sense that no reasonable tribunal similarly circumstanced would have arrived at the impugned decision.

It is neither feasible nor desirable to attempt an exhaustive definition of what amounts to an error of law for the categories of such an error are not closed. But it may be safely said that an error of law would be disclosed if the decision-maker asks himself the wrong question or takes into account irrelevant considerations or omits to take into account relevant considerations (what may be conveniently termed an Anisminic error) or if he misconstrues the terms of any relevant statute or misapplies or misstates a principle of the general law."

[Emphasis Added]

[24] We further note the Court of Appeal case of Airspace Management Services Sdn Bhd v. Col (B) Harbans Singh Chingar Singh [2000] 1 MLRA 664 at 669, referred to by the High Court in its further elucidation of the test as follows:

"On the other hand, we accept, of course, that it is entirely competent for the High Court in certiorari proceedings to disagree with the Industrial Court on the conclusions or inferences drawn by the latter from the proved or admitted evidence on the ground that no reasonable tribunal similarly circumstanced would have arrived at such a conclusion or drawn such an inference. An erroneous inference from proved or admitted facts is an error of law; not an error of fact."

[Emphasis Added]

Whether The "Transfer" Clause That Refers To The Employee Having To Perform His Services In The Current Location Or "In Such Other Locations As Reasonably Directed By The Company" Would Subject The Transfer Exercise To The "Reasonableness Test" As Part Of The "Contract Test" That The Parties Have Agreed

[25] The Federal Court had clarified and confirmed that the test for constructive dismissal is the "contract test" and not the "reasonableness test" in its most recent pronouncement in Tan Lay Peng v. RHB Bank Berhad & Anor [2024] 5 MLRA 171; [2025] 1 MELR 699 in answer to the leave question posed which was:

"Is there a difference in the contract test or reasonable test in light of major developments in industrial jurisprudence?"

[26] In answering the question posed the Federal Court declared as follows:

"[18] It is a trite principle of law in Malaysia that the applicable test in constructive dismissal cases is the contract test and not the reasonableness test. The contract test is whether the conduct of the employer, in its action or series of actions, constitutes a fundamental or repudiatory breach that goes to the root of the employment contract or where the employer has evinced an intention no longer to be bound by the express or implied terms of the contract. Constructive dismissal is where the employee claims that he has been dismissed due to the employer's conduct. This can be said as "deeming dismissal" by the employer. The burden is on the employee to prove, on the balance of probabilities, that he has been constructively dismissed."

[Emphasis Added]

[27] The locus classicus of the law on constructive dismissal is traceable to the then Supreme Court case of Wong Chee Hong v. Cathay Organisation Malaysia Sdn Bhd [1987] 1 MELR 32; [1987] 1 MLRA 346 where Salleh Abas LP (as he then was) referred to the Court of Appeal case in England, Western Excavating (ECC) Ltd v. Sharp [1978] IRLR 27 for the following proposition of law in expounding the position under our Industrial Relations Act 1967 as follows:

"The common law has always recognized the right of an employee to terminate his contract of service and therefore to consider himself as discharged from further obligations if the employer is guilty of such breach as affects the foundation of the contract or if the employer has evinced or shown an intention not to be bound by it any longer. It was an attempt to enlarge the right of the employee of unilateral termination of his contract beyond the perimeter of the common law by an unreasonable conduct of his employer that the expression "constructive dismissal" was used. It must be observed that para. (c) never used the words "constructive dismissal". This paragraph simply says that an employee is entitled to terminate the contract in circumstances entitling him to do so by reason of his employer's conduct. But many thought, and a few decisions were made, that an employee in addition to his common law right could terminate the contract if his employer acted unreasonably. Lord Denning MR, with whom the other two Lord Justices in the case of Western Excavating (supra) reiterating an earlier decision of the Court of Appeal presided by him (see Marriott v. Oxford and District Co-operative Society Ltd [1969] 3 All ER 1126) rejected this test of unreasonableness. In no uncertain terms, the learned Master of the Rolls declared that the test of dismissal in respect of para. (c) is a contract test...

Thus, it is clear that even in England, "constructive dismissal" does not mean that an employee can automatically terminate the contract when his employer acts or behaves unreasonably towards him. Indeed if it were so, it is dangerous and can lead to abuse and unsettled industrial relations. Such proposition was rejected by the Court of Appeal. What is left of the expression is now no more than the employee's right under the common law, which we have stated earlier and goes no further. Alternative expression with the same meaning, such as "implied dismissal" or even "circumstantial dismissal" may well be coined and used. But all these could not go beyond the common law test.

Turning back to our case under appeal, it is not enough for the learned Judge in the Court below to say that constructive dismissal has no application to the interpretation of s 20 of the Industrial Relations Act. He must go further and say which of the two alternative views on constructive dismissal has no application and if so, why? Whilst we think that"constructive dismissal" with unreasonableness test does not apply, it will be wrong for anyone to hold that "constructive dismissal" with contract test does not apply. Perhaps in the context of our law, it is better that we do not use the terminology at all.

When the Industrial Court is dealing with a reference under s 20, the first thing that the Court will have to do is to ask itself a question whether there was a dismissal, and if so, whether it was with or without just cause or excuse. Dismissal without just cause or excuse may well be similar in concepts to the UK legislation on unfair dismissal, but these two are not exactly identical. Section 20 of our Industrial Relations Act is entirely different from para (c) of s 55(2) of the UK Protection of Employment Act 1978. Therefore we cannot see how the test of unreasonableness which is the basis of the much advocated concept of constructive dismissal by a certain school of thought in UK should be introduced as an aid to the interpretation of the word "dismissal" in our s 20. We think the word "dismissal" in this section should be interpreted with reference to the common law principle. Thus it would be a dismissal if an employer is guilty of a breach which goes to the root of the contract or if he has evinced an intention no longer to be bound by it. In such situation, the employee is entitled to regard the contract as terminated and himself as being dismissed. (See Bouzourou v. The Ottoman Bank [1930] AC 271 and Donovan v. Invicta Airways Ltd [1970] 1 Lloyd's Rep 486).

[Emphasis Added]

[28] Whilst the test is that of the "contract test" and not the "reasonableness test", the Federal Court in Tan Lay Peng (supra) nevertheless held as follows:

"[50] In the circumstances and based on reasons alluded to earlier, the answer to the leave question is as follows:

There is a difference between the contract test and the reasonableness test. The appropriate test for determining a constructive dismissal case is the contract test. The reasonableness of the employer's conduct is a factor that may be taken into consideration in determining whether there is any fundamental breach of the contract of employment or an intention no longer to be bound by the contract."

[Emphasis Added]

[29] The present 3 appeals fell for a different consideration because of the way that the relevant "Transfer" clause is worded in Noramidah's case in Appeal 477 with the term "reasonableness" being crafted into cl 8 and in the other 2 earlier cases of employment, with the same term being grafted into the "Transfer" clause when the Company reiterated the terms of the Contract of Employment that were set out in the Notice of Transfer dated 27 September 2017 to each of the Claimants that reads at para (b) thereof as follows:

"We also wish to take this opportunity to re-affirm the following:

...

(b) Transfer of employment

You may be required to perform your services to the Company or any of its subsidiaries or associated entities in the current location of your employment with the Company, or such other locations as reasonably directed by the Company. The Company reserves the right to transfer your employment to its subsidiaries or associated companies."

[Emphasis Added]

[30] That was exactly how Noramidah's contract in cl 8 was worded where the "Transfer" clause was concerned. It is true that the original "Transfer" clause in cl 7 in Saharunzaman's case and in cl 3 in Razif's case do not have the element of "reasonableness" in the exercise of transfer by the Company. (See the Table above.)

[31] The Industrial Court observed that Noramidah's contract dated 14 April 2008 was a more recent contract compared to the earlier ones in Saharunzaman's case dated 20 June 1995 and Razif's case dated 1 February 2002 and surmised as follows:

"[28] ...The Company maintained that it is the Company's right/prerogative to transfer the Claimant which transfer order must be obeyed by the Claimant and the Claimant had in fact disobeyed this order, the Company brought the attention of this Court to cl 7 of the Claimant's appointment letter dated 20 June 1995 to emphasize this right of the Company to effect the transfer of the Claimant. For convenience cl 7 reads as follows:

"TRANSFER

Depending on Company's needs or requirement, you may be required to serve anywhere in Malaysia either within the company or any of the subsidiary companies of the Group. Appropriate assistance will be provided for such transfers."

[29] This Court had compared cl 7 of the Claimant's appointment letter with cl 3 of the 3rd claimant's appointment letter dated 23 January 2002 and cl 8 of the 2nd claimant's appointment letter dated 7 April 2008.

[30] This Court had noted a startling yet commendably humane approach taken by the Company through the passage of time wherein the latest appointment letter of its employee (2nd claimant's, dated 7 April 2008) when compared to the earliest appointment letter which is dated 20 June 1995 had included a more palatable and non-arbitrary clause in matters touching transfers of its employee. The latest transfer letter had included as its terms that the transfer must be one that is reasonably directed by Company.

[31] Clause 8 of the appointment letter dated 7 April 2008:

TRANSFER

You will be initially be based at our SS Qstop Station Batu Caves but you may be required to perform your services to the Company or any of its subsidiaries or associated entities, or at such other location, elsewhere in Malaysia as reasonably directed by the Company

[Emphasis Is This Court's]

[32] The Company by including this latest wording had made known its current position in as far as transfers are concerned. It cannot be the intention of the Company that it is only expected to be reasonable to the 2nd claimant and continue to be arbitrary and unyielding to the other Claimants in as far as transfers are concerned. This provision for the Company to act reasonably in matters affecting transfer is part of the Company's fundamental contractual undertaking which the Company cannot abdicate or abandon..."

[Emphasis Added]

[32] Lest it be still argued that only Noramidah's contract has the "reasonableness" requirement included into the "Transfer" clause and not that of Saharunzaman and Razif, one must then hasten to add that the Company in its Transfer Notice had treated the element of "reasonableness" as being part and parcel of the "Transfer" clause for all its employees. It was not a case of the Company discriminating against earlier employees and only giving the contractual benefit of "reasonableness" only to those who joined the Company later like in Noramidah's case in cl 8 thereof.

[33] This had not escaped the notice of the Industrial Court for it has observed as follows:

"[32] ... All transfers to other location as reasonably directed by the Company is also part of the Company's new position by simply looking at the Notice of Transfer dated 27 September 2017 under "Transfer of Employment" where the Company reaffirms this position."

[Emphasis Added]

[34] The difference is not subtle but significant and substantial. When the requirement of "reasonableness" is an agreed contractual term of the parties relating to the exercise of the managerial prerogative of transfer, then effect must be given to it. When the Company's transfer exercise is being challenged on ground of unreasonableness, mala fide and for a collateral, colourable or oblique purpose, then the Company's action is open for scrutiny by the Court.

[35] In analysing and assessing if the conduct of the Company and the circumstances of the case justifying the transfer as being reasonable or otherwise, the context that triggers the transfer must be examined as a whole. That examination does not convert the "contract test" into the "reasonableness test". It is very much a "contract test" with the requirement of "reasonableness" built into it as part of the contractual term on "Transfer" that the Company had agreed with its employees.

[36] As to whether a breach of the agreed contractual requirement of "reasonableness" is one going to the root of the contract or one where the Company had evinced its intention not to be bound by the terms of the contract, that would very much be a finding of fact that ordinarily the Industrial Court would be best positioned to decide by taking into consideration all relevant factors and not taking into consideration irrelevant factors and asking the right questions and giving reasonable answers to the questions posed. One would have to look at the proximate cause of the transfer and discern if it is proper or perverse in the context and circumstances of the case and the conduct of the parties.

[37] Whilst our hair may all be black, our heart's intention may be concealed and camouflaged to get rid of an inconvenient remnant that remains after a corporate restructuring exercise. Generally, motives and motivations are not relevant in a pure "Transfer" clause but where "reasonableness" is embedded into the transfer decision and exercise, such a clause cannot be weaponised to consign an employee to a faraway posting on a flimsy and fanciful reason. Hence the expression to be "sent to Siberia" where a transfer was more a punishment as in being expelled, exiled or cold-storaged.

[38] With the greatest of respect, the High Court did not appreciate the nuanced approach taken by the Industrial Court when it concluded that as the Industrial Court had considered the element of "reasonableness", it had inadvertently and erroneously applied the "reasonableness test" when in reality it should have applied the "contract test."

[39] There is nothing in the freedom of contract in employment law that bars an employer from agreeing that its managerial prerogative of transfer be subject to the overarching consideration of reasonableness for some faraway transfers may be not only disruptive, but deleterious and even damaging to the affected employee and his family. In fact, companies that have such a Transfer clause would attract talents for its employees would know that any transfer to some faraway places would only be exercised as a last resort with additional monthly transfer allowance being given to facilitate travel back on weekends. For senior management and highly skilled employees, companies would even factor this into the billings for their clients.

[40] Whilst highly skilled employees would have little problem adjusting with higher pay package and perks for outstation or overseas posting, lower skilled employees would feel the pinch especially as in these appeals where there is no additional monthly transfer allowance other than a one-off disruption allowance and accommodation allowance whilst waiting one's finding of a more permanent place to reside in one's new posting.

[41] It was in that context that the Industrial Court took the approach below, mistakenly interpreted by the High Court to be a "reasonableness test" approach that the Federal Court had clearly overruled:

"[20] Having stated the law above, this Court will now move to the facts of this case for its determination. It must be further stated here that the Claimant's case being one of constructive dismissal, the Claimant must give sufficient notice to his employer of his complaints that the conduct of the employer was such that the employer was guilty of a breach going to the root of the contract or whether he has evinced an intention no longer to be bound by the contract as stated in the case of Anwar Abdul Rahim (supra).

...

[33] Now the question that needs to be answered is whether given the circumstances of this case, could this transfer be regarded as reasonable in the circumstances of this case and as acting reasonably in matters concerning transfer which is a fundamental contractual obligation of the Company towards its employees? This Court holds that in the event of any unreasonable transfer exercise by the Company concerning its employees then it would be a breach that goes to the root of the contract

...

[38] ...The conduct of the Company is totally unreasonable despite the Company being fully aware that as part of the Claimant's terms of contract of employment with the Company, the Company must act reasonably in matter affecting transfers (see also Company's letter to Claimant dated 27 September 2017 on transfer of employment which must be reasonably directed by the Company). This goes to the root of the contract/agreement between the parties.."

[Emphasis Added]

[42] We conclude that the Industrial Court did not err in applying the "contract test" and taking into consideration the agreed requirement of "reasonableness" as a term of the Contract of Employment.

Whether In The Context Of The Events Triggering The Notice Of Transfer And The Conduct Of The Company, The Transfer Exercise Was mala fide And Manifested The Intention Of The Company Not To Be Bound By The Contract

[43] The Company first informed its 23 employees about NAM taking over its Bukit Beruntung branch and its Sungai Choh service centre by its Internal Memo dated 24 August 2017 at encl 8 PDF p 110. The caption of the subject reads: offer of Employment at Nagoya Automobile Malaysia (NAM). The Company stated that its Board of Directors had recently increased its equity in NAM through Perusahaan Otomobil Kedai Sdn Bhd (POSB) to 30%. The employees were encouraged to favourably consider the offer by NAM as part of the opportunity to learn the best practices in sales and service and which experience gained would be helpful in meeting the challenges ahead especially in the field of Customer Satisfaction.

[44] The Company informed its employees that the employment would be for a period of 2 years based on the same benefits and terms as what they were then enjoying. There was also the prospect of undergoing training in Japan to gain knowledge and experience in the field of Customer Service Satisfaction where NAM was a reputed trailblazer.

[45] This was followed by letters dated 13 September 2017 (See a typical letter in encl 4 PDF p 93) where the Company spelt out the terms of the offer of employment by NAM. The Company said that it appreciated difficulties involved in making such a decision to accept NAM's offer of employment for 2 years and that the Company's management appreciated and welcomed the employees' decision.

[46] Perhaps the difficulties could have been buffered if not for the need of all employees who wished to accept NAM's offer, to first resign from the Company effective 1 October 2017 as set out in paragraph 2 of the letters of 13 September 2017.

[47] At paragraph 3 of the said letter the Company stated that it would re-offer employment to the employees after the 2 years are over including retaining the post for the employee concerned and the years of service with the Company. However, the Company reserved its right to place the employee at any branches of the Company subject always to availability of a vacancy. The employee concerned was required to give a month's notice before the 2-year term expires.

[48] The Company even gave a sweetener that the employee may be promoted if there is a vacancy available. However, if the employee were to terminate his employment with NAM or that NAM terminated his employment before the expiry of the 2-years period, then the Company would decide on a case-by-case basis as to whether to take the employee back into its employment.

[49] The employees who had made such a difficult decision to join NAM were given until 18 September 2017 to sign the acceptance letter and to return the same to the Company.

[50] One wonders why there was even a need to resign from Company if the transfer of employment to NAM was just for a period of 2 years, for the good of the employees concerned with opportunities of being trained and in the process to acquire specialised skills and experience in Customer Satisfaction. It would be so much neater and more assuring to the employees affected if the 2-year period is just a secondment and at the end of which they could always rejoin the Company for they have not resigned from the Company.

[51] As NAM was not recognising their years of service with Perodua in NAM's 2-year contract with the employees, it would appear that all the years of service would be lost should they choose to remain with NAM at the end of the 2-years period. Should they choose to come back to employment with Perodua, it would appear that they would have to re-apply to join Perodua again as they had to resign from Perodua before they could join NAM for a 2-year term.

[52] The Industrial Court had a point in observing that the Offer of Employment by NAM was riddled with uncertainties such that if one were to be unlawfully terminated by NAM during the 2-year period, what would one's position be when it comes to the whether the years of service with Perodua would be recognised for the purpose of compensation.

[53] The Industrial Court rightly sketched the possible conundrum the Claimants may find themselves to be in whether during or after the 2-year fixed term contract with NAM as follows in its Award:

"[41] This Court had also considered the evidence of COW 1 touching on the apparent fear of loss of years of service with the Company as anticipated by the Claimant is unfounded and this is because should the employee (the Claimant here) decide to return to the Company after the expiry of the 2 year period, their last position in the Company and their years of service in the Company and NAM would be recognized by the Company and remain unaffected. With respect this Court cannot find any substance in this piece of evidence of the COW1. This Court is of the view that the fear of the Claimant has merits in it and not unfounded as alleged by the Company. A careful reading of the Company's letter dated 24 August 2017 to the Claimant and letters of offer of employment as seen in Company's Bundle of Documents (COB4), offering employment with NAM will drive home the point. The letters offering employment to other employees though seemingly attractive on the surface but upon a deeper scrutiny clearly show that these employees are not guaranteed security of tenure as claimed by the Company. Assuming before or after the 2 years of service with NAM, NAM or the Claimant decides to end the contract of employment for whatever reason, then the employees reemployment into the Company is not automatic but on a case by case basis which creates uncertainty of re-employment. The Claimant/employee will also potentially lose all his years of service with the Company for which benefits may accrue. What if in the exercise of this re-employment on a case by case basis, the Claimant is not accepted back by the Company? What if he is terminated by NAM for some reason and the Claimant takes up a case and succeeds in the Industrial Court? Would the compensation for years of service be the duration of employment with NAM or calculated from the date when the Claimant commenced employment with the Company? The Company is totally silent on these issues and one cannot expect a mere employee with little or no legal training and mind to understand these legal niceties which works to the detriment of the employees.

[42] The conduct of the Company in engaging in such manoeuvres clearly demonstrates to this Court of unfair labour practice where the workmen in this Country are to enjoy the benefits of security of tenure of his employment. The conduct of the Company for all intents and purposes is to outflank this security of tenure by what the Company had done or likely to do to the employees."

[Emphasis Added]

[54] Whilst the Company said that it would keep the posts available during the 2-year period but one knows that with the passage of time, nothing remains static and that the one unchanging certainty compounded by the current of time is that nothing is certain or unchanging.

[55] For these 3 employees who did not take up the offer, the Company could not even keep their posts for them for even a month for on 27 September 2017 they each received a Notice of Transfer to Kota Kinabalu for Saharunzaman, Kuching for Noramidah and Kuala Terengganu for Razif. Perhaps that is where the Company would have to transfer the employees concerned after the 2-year period of training is up.

[56] It was unreasonable for the Company to have insisted that the employees must resign from its employment before taking up the offer of employment by NAM for a 2-year term. It is as if the employees' permanent contracts with Perodua were being substituted with a 2-year fixed-term contract. It is different if the offer of employment by NAM is on terms no less favourable and with the years of service with Perodua being recognised by NAM. Even then, being a new employer and a separate legal entity, the affected employee would have the option to accept the offer or not to.

[57] Should they not accept the new offer by the new company, then a decent thing for the current company to do would be to pay termination and layoff benefits to the affected employees assuming that the whole operation and business of the current company had been transferred to a new company.

[58] In fact, the Transfer clause for all 3 Claimants in paragraph (d) of their Notice of Transfer includes that the Company reserving its right "to transfer your employment to its subsidiaries or associated companies." With a 30% equity stake in NAM, NAM is very much an associate company of Perodua under the Malaysian Accounting Standard Board's treatment of associated companies and that of the Malaysian Financial Reporting Standards.

[59] We appreciate that it is for the Company Perodua to decide on how the corporate restructuring exercise should be pursued, both for streamlining businesses within the group and for profitability in joint-ventures and the like. However, such corporate exercise should not leave employees worse off as in having to resign first before availing oneself of what the Company said would be for their long term benefit and gain and then facing the uncertainty of having to resign first before applying to rejoin the Company again. When the same can be achieved by just a mere secondment or a transfer to NAM for a 2-year term, a natural question raised would be why go through all the hassle.

[60] Even if a secondment or transfer for a 2-year period cannot be done for all the employees for there were 23 of them to manage, surely for the 3 here that stood up for their rights, it cannot be too difficult to transfer them to NAM for a 2-year term and then to keep their posts for them during that 2-year period together with their accumulated years of service with the Company.

[61] The fact that the Company chose so soon thereafter after the rest had accepted the Offer of Employment by NAM by 18 September 2017 to transfer them to far-flung locations by a Notice of Transfer dated 27 September 2017 and having to report for work at their new stations 3 days later on 1 October 2017 would be most unreasonable as a run-up to the transfer of business exercise.

[62] The action of the Company is a manifestation of its intention not to be bound by the terms of the contract for there was nothing preventing the Company from achieving the same effect by transferring the 3 employees to NAM for a 2-year period without any loss of seniority and on the same terms and conditions. The fact that others accepted the 2-year term with NAM and the uncertainty of having to re-apply to join back Perodua does not mean that these 3 Claimants had to do likewise and more so when contractually they perceived that the Company was trying to unilaterally alter their permanent employment to a term contract with its attendant uncertainties thereafter.

[63] The action of the Company in requiring the affected employees to have to resign first even when the new company NAM did not recognise their years of service with Perodua in its Offer of Employment for a fixed 2-year term would be unreasonable in the context of the case in the aftermath of a restructuring exercise, applying the contract test as the Company had evinced its intention not to be bound by the terms of the contract which terms included the element of reasonableness in its transfer decision.

[64] The 3 Claimants wrote a few letters of appeal to the Company but to no avail. It was not unlike a case where these 3 Claimants were inconvenient statistics that had to be gotten rid of and they were driven out of employment when the Company exercised its so-called managerial prerogative to transfer them to the 3 faraway locations already mentioned.

[65] The more unusual the terms of a transfer of business with respect to the Offer of Employment by a new entity, the greater the need for the company left with employees not taking up the offer to show that the transfer is not done mala fide or for a colourable purpose to force the employees out of employment without the need to pay any termination or lay-off benefits.

[66] Indeed the 3 Claimants had implored the Company in their various appeal letters, to consider their family commitments and to transfer them to any available vacancy nearby or as a last resort to pay them the termination and lay-off benefits but the Company must have deemed them to be non-compliant and a pain.

[67] The Company made a fuss that the Claimants did not approach them after receiving the Notice of Transfer to discuss the matter. The Claimants' evidence was that the Company refused to see them when they wanted to personally hand in their first appeal letter dated 28 September 2017 and reiterated that they have to report for duty at the designated locations. It is for the Company to reach out to the affected employees and to explore with them what are the various options available as in thinking out of the box and understanding the needs, interests and concerns of the affected employees in the Claimants.

[68] After all these are not very highly skilled workers and if at all they are needed to train the new employees from Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu, perhaps they could be there for a limited time and when a vacancy nearby in the Klang Valley is available, they can then come back. Surely it cannot be that difficult to train someone to be a mechanic or a sales advisor and it would probably be cheaper to source someone from these various locations rather than transferring there someone from Rawang. We recall that the Company had tried to assure the other affected employees that their posts would be kept for them whilst they were being trained for 2 years under NAM.

[69] We can only hope that after the 2 years is over the other employees would not have to suffer the same fate of being transferred far away on ground that there is no vacancy for their posts in the current location. It is little comfort to say that if they need more time to make the transition to Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu then they may so request for the shock of a need to report for duty within 3 days may be so overwhelmingly real that what remains is just postponing reality.

[70] It is to be noted that the Company's letter giving this so-called indulgence of extra time was dated 9 October 2017, the same day as the Letter to Show Cause why disciplinary action should not be taken against them for not reporting for duty, which letter must be replied within 2 days failing which they shall be deemed to have no good reason. The bona fides of the Company in giving the reprieve of time is seriously doubted.

[71] Considering the context of the case where the Claimants had to exchange their permanent contract with Perodua for that of a 2-year contract with NAM coupled with a mandatory resignation first from Perodua before accepting the 2-years contract with NAM, and the consequence of not taking up the Offer of Employment by NAM which was a transfer to Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu respectively, one cannot help but make the inference that the transfer exercise was a kind of "punishment" meted out to the Claimants for not towing the line. The transfer exercise was thus mala fide when tested against the requirement of reasonableness which the parties had agreed as part of the terms of the contract.

[72] The Company's action, justified on the high ground of managerial prerogative, was in reality pursued to drive the Claimants out of employment without the need to pay them any termination and lay-off benefits if really there were no vacancies nearby for them to fill in other branches and service centres. Such an action of the Company went to the root of the contract and was a fundamental breach, where the Claimants were right in treating themselves to have been constructively dismissed.

Whether Having Regard To The Circumstances Of Each Of The Employees, The Transfer Exercise Was Mala Fide For A Collateral Purpose

[73] Given that the requirement of "reasonableness" is written into the terms of each of the contracts of employment of the Claimants, in Noramidah's case by it being included in the Transfer clause and in all the 3 Claimants's cases by being imported into it by reference to it in each of the Notice of Transfer in the terms in paragraph (b) thereof, the Industrial Court did not err in considering the relevant factors in determining whether the Transfer was reasonable having regard to the circumstances of each of the Claimants.

[74] In Saharunzaman's case he had served the Company for 22 years and is also an OKU with his disability being expressed as "physical" and having to undergo medical treatment during the material time. He also has a working wife with 5 school-going children. His last drawn salary as a Service Advisor was a mere RM3,085.00.

[75] In Noramidah's case, she had put in 9 years of service with the Company. She has a working husband and 3 school-going children. Her last drawn salary as a Service Advisor was RM3,578.00.

[76] As for Razif, he had worked for the Company for 15 years. He has one child with another child on the way in November 2017. He was also taking care of an aged and sick mother. He was a mechanic with a last drawn pay of RM2,778.00.

[77] Whilst the salary and the other terms and conditions of service remained the same, in reality there will be a higher costs to be incurred as additional accommodation had to be rented and additional travelling expenses in terms of airfares coming back to see the family as often as possible during the weekends.

[78] The one-off allowances in terms of Disruption allowance, temporary hotel accommodation whilst looking for a more permanent place to stay in, transport allowance for personal effects and insurance and without an additional reasonable monthly Transfer allowance, would in reality leave the Claimants with less disposal income.

[79] It is not so easy as to say the whole family can be uprooted and relocated there in the new locations as children have their network of friends in schools, the families too have sunk their roots into the communities here with the network of support from family members and friends. Their low pay with no increase in the monthly allowance does not help them at all for how much may one stretch a ringgit with the high costs of living.

[80] We cannot expect a parent to bond and nurture his or her children by way of remote control via Zoom communication. The physical interaction and presence of both parents in the growth and development of the children cannot be dispensed with.

[81] If the Company is to be believed that it will retain the posts of the affected employees for the 2 years of contract with NAM, then the Company should explore if the same may be achieved by transferring or seconding these 3 Claimants to NAM and when the 2-year is over, they would continue to work for Perodua, subject always to availability of vacancies.

[82] Each of the Claimants had suggested that if they had to be transferred out then perhaps they could be transferred to any branches nearby and if not then the Company should pay them their termination and lay-off benefits and not transfer them to a faraway location where it would be too disruptive for them to go and indeed they would be financially ruined in the process as discerned by the Industrial Court.

[83] If really there were vacancies in these places in Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu, it would be cheaper and more cost-effective to hire someone from these places and then give them the necessary training and if need be, the Claimants may be sent there for a brief period to train the new recruit.

[84] Where the Company can exercise its right under the Transfer clause to transfer the Claimants to its associated company to achieve the same result, for after all it holds a 30% equity stake through its parent investment company in NAM, its refusal to do so would smack of bad faith and an attempt to wriggle itself out of the contract. Such a conduct though ostensibly made to look like a bona fide transfer exercise is in reality driving the employees out of employment and victimising them.

[85] Requiring the Claimants to resign from Perodua first would be inflexibly suspicious if the Company's intention is to welcome them after 2 years with NAM is over and retaining their posts for them. It would make more sense, give more assurance to the employees and less cause for anxious consideration if there is no requirement to resign from Perodua but only a transfer or secondment to NAM.

[86] Once an employee is made to resign before taking up the 2-year fixed contract with NAM, the harsh reality of having to apply afresh to join Perodua would come with it the uncertainty of whether the job is still available after 2 years and perhaps a need to be transferred elsewhere and hopefully not to some faraway locations like the Claimants here found themselves.

[87] It must not be forgotten that this is not a case where the new employer NAM offers a permanent employment on terms no less favourable than Perodua with the years of service in Perodua being recognised in NAM's new contract with the employees. It is not just a raw deal but a subtle attempt to unilaterally vary the terms of the employment contract and thus evincing an intention not to be bound by it.

[88] In the totality of the circumstances of each of the Claimants, this Transfer exercise with a 3-day Notice of Transfer cannot be said to be bona fide and reasonable but one constrained to compel the Claimants into resigning without the need to pay any retrenchment benefits. The unholy haste with which the Transfer was effected was not unlike one designed to shock and awe, leaving the Claimants disoriented, stunned, confused and overwhelmed and any reprieve later that more time could be given if they needed was of little help. The collateral purpose could be inferred and deduced from the conduct of the Company.

[89] Both the manner and motive of the Transfer exercise do not pass muster the contract test of reasonableness that the Company had promised the Claimants in their Contracts of Employment.

Whether The Industrial Court And The High Court May Take Notice Of Illegality Once It Is Raised And Led In Evidence With Respect To The Absence Of A Valid Work Permit For The Purpose Of Reporting To Work In Kota Kinabalu And Kuching

[90] It is true that the lack of a work permit or employment pass was not pleaded by the Claimants Saharunzaman and Noramidah for their respective reporting to work on 1 October 2017 in Kota Kinabalu and Kuching respectively. However, it had been led in evidence and the Company's sole witness COW 1 Mariam Binti Ibrahim, who was the Head for Human Resources, admitted under cross-examination that there was no work permit applied for these 2 Claimants.

[91] The Company's witness had even proffered an explanation which is that the Application for a Work Permit would be made at a later date after the employee had reported to work. That would fly against the requirement of the law and that would be so even if the 2 Claimants affected may not be conscious of the legal requirement of having a work permit before reporting to work. It is a given that ignorance of the law is no excuse from complying with the law.

[92] Both parties had also identified the issues in their submissions before the Industrial Court and had submitted on their respective stand on the absence of the relevant work permit or employment pass. There was thus no prejudice occasioned to any party, in particular to the Company which of all parties, should be the one more in the know.

[93] The Company's witness Puan Mariam said that the Company would give the employees the relevant documents to apply for the work permit which process would take about 3 weeks and in the meanwhile the employees can start work. See encl 9 PDF p 79 in her re-examination. In the absence of evidence from the State Immigration Office, one cannot presume that the requirement of the law can be ignored for at the immigration counter upon arrival by plane, the 2 Claimants would have to suffer the risk of not being allowed entry into Kota Kinabalu and Kuching if they were to declare that they were entering for work purpose and with no work permit. To say that they were coming in on social visit would be to make a false declaration.

[94] The employees should not be exposed to criminal prosecution for violating the Immigration and Labour laws of Sabah and Sarawak. Under the Malaysia Agreement 1963, both Sabah and Sarawak have certain autonomy with respect to control of entry into and work in Sabah and Sarawak even for West Malaysians especially those in the private sector.

[95] For the Company to require the transferred employees to start work without a valid work permit or employment pass would be illegal and the Court or any Tribunal must take cognisance of it when the issue is raised, though it may not have been pleaded. To insist on having to report to work without a work permit having been applied for and obtained would involve the affected employee committing a criminal offence. Such a breach of the immigration laws of Sabah and Sarawak by the Company would be a breach that goes to the root of the contract and the Company's action in citing the 2 Claimants for misconduct in not reporting to work would be most unreasonable in the circumstances of the case. See s 66 Immigration Act 1959/63 and regs 5, 16 and 39 of the Immigration Regulations 1963 where the punishment upon conviction is 6 months imprisonment or a fine not exceeding RM1,000.00 or to both imprisonment and fine.

[96] Our Federal Court had pronounced on number of occasions that the Court would take cognisance of illegality once it is raised in evidence though not specifically pleaded and would uphold a defence based on illegality as a matter of public interest and policy. The Federal Court in Merong Mahawangsa Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Dato' Shazryl Eskay Abdullah [2015] 5 MLRA 377 reiterated the principle as follows at pp 391-392:

"Therefore, the question of illegality would not depend on pleading or procedure, or on who first might or should produce the documents. It would be a question of substance, of which, if necessary, the court would of its own motion take cognisance, and to which the court would give effect (Vita Food Products Inc v. Unus Shipping Co Ltd (in Liquidation) [1939] 1 All ER 513 per Lord Wright). 'when an allegation of illegality is made, and a suggestion is made to the court that the contract is illegal, notwithstanding the fact that the illegality is not pleaded, the court is bound to take cognisance of the fact that the contract may be illegal, and, if it is illegal, the court cannot enforce it' (Marles v. Philip Trant & Sons Ltd (Mackinnon, Third Party) (No 1) [1953] 1 All ER 645 per Lynskey J). 'A judge is constrained to decide those issues raised by the pleadings in an action. The judge cannot decide issues not contained in the pleading because the judge has jurisdiction only to deal with those matters that the parties have chosen to bring before him in their pleadings. This rule is subject to exceptions where there is a public interest and the judge on his own initiative considers a matter of which he has become aware during the course of a case, although it is not contained in the pleadings, for example, cases of illegality or of conduct contrary to public policy' (Swann, Evans, Ferguson and Crawshay (a firm) v. Hill and Another, Court of Appeal (Civil Division) per Roch LJ, 8 March 2000).r

Most recently, in Les Laboratories Servier & Anor v. Apotex Inc & Ors [2014] UKSC 55, the Supreme Court of England per Lord Sumption (with whom Lord Neuberger and Lord Clarke agreed) affirmed that a judge is bound to take up the illegality defence:

The illegality defence, when it arises, arises in the public interest, irrespective of the interest or rights of the parties. It is because the public has its own interest in conduct giving rise to the illegality defence that the judge may be bound to take the point of his own motion, contrary to the ordinary principle in adversarial litigation.

Thus, 'It is well established that if a contract is, on its face, illegal, the court will not enforce it, whether illegality is pleaded or not'. Lediaev v. Vallen [2009] EWCA Civ 156 per Aikens LJ)."

[Emphasis Added]

[97] The action of the Company in issuing the Letters to Show Cause for the misconduct of insubordination in not reporting to work at the new locations would be unreasonable and indeed would evince an intention not to be bound by the contract where the Company had an implied duty of mutual trust and confidence that it would do everything necessary to ensure that the 2 Claimants here are lawfully employed in compliance with the Immigration and Labour laws of Sabah and Sarawak. It is not for the Company to kick the ball to the affected employees and then placed the obligation on them to obtain the work permit and in the meanwhile expecting them to be working.

[98] Under the Sabah Labour Ordinance in ss 118 and 130L and the Sarawak Labour Ordinance in ss 119 and 130L, the obligation to comply with the Licence to Employ Non-Resident Employee rests with the Employer though an employee may well be aiding and abetting in the offence.

[99] Whether or not this was a case of the Company in its haste to transfer the 2 Claimants had forgotten to apply for the necessary work permit, the fact remains that the 2 Claimants were expected to report to work without a work permit. In the circumstances of the case the 2 Claimants were entitled to treat themselves as being constructively dismissed.

Whether The Claimants Had Discharged Their Legal Burden Of Proving Constructive Dismissal In The Light Of The Evidential Burden Of The Company To Show That The Only Vacancies Available Were In Kota Kinabalu, Kuching And Kuala Terengganu

[100] It is established that the legal burden rests with the Claimants who claimed that they had been constructively dismissed. Here, as the requirement of reasonableness is an agreed term of the contract where the Transfer clause is concerned, the Claimants had alluded to the contexts leading to the Transfer and the circumstances of their case to prove that the contract test of reasonableness had not been satisfied. Instead the Company had evinced its intention not to be bound by the terms of the contract in its insistence that they should report for duty at the various locations or suffer a domestic inquiry into their misconduct of insubordination.

[101] The evidential burden is for the Company to discharge in the light of the evidence adduced by the Claimants in proving their cases of constructive dismissal. Like the Industrial Court, we are not impressed by COW 1 who claimed that she had documents to show that the only vacancies available were in Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu respectively but that the documents were not before the Industrial Court. It cannot be for the Company to expect the Industrial Court to believe its witness on a mere say-so. It is axiomatic that when any fact is especially within the knowledge of any person, the burden of proving that fact is upon him under s 106 Evidence Act 1950.

[102] As the Head of Human Resources we would have expected documents showing amongst others the following:

(i) The number of Mechanics and Service Advisors in the other branches and service centres and the over-capacity or otherwise of these branches vis-a-vis the sales and service volume of the vehicles for the relevant period;

(ii) Whether there had been resignations from these positions and whether these positions had remained unfilled or otherwise;

(iii) Whether there is a real need at the Kota Kinabalu, Kuching and Kuala Terengganu branches respectively with respect to Service Advisors and Mechanics where vehicle sales and service are concerned for the relevant period;

(iv) Whether it would be cheaper and more cost-effective to engage locals in these 3 locations to fill the vacancies.

[103] The Industrial Court rightly observed that the transfer must be premised on the genuine needs or requirements of the Company as even the original clause on Transfer in the case of Saharunzaman and Razif referred to that. It observed as follows:

"[35] This Court had perused the entire evidence and documents presented in Court and undoubtedly not satisfied that the transfer is made purely on the basis of the needs or requirement of the Company although COW had given evidence that it is an operational requirement. The Company had not demonstrated to this Court that the Kota Kinabalu 2 Service Centre is in need or requires a service advisor at the time of the transfer being effected affecting the Claimant. This is further fortified by the submission of the Company that the reason for the transfer among others is purely on grounds that Bukit Beruntung Branch and Sungai Choh Service Centre had been taken over by NAM and also considering the all-important right of the Claimant's livelihood (see paragraph 8 page 5 of the Company's written submission)."

[Emphasis Added]

[104] It must also be borne in mind that the Claimants had asked the Company to explore the possibility of paying them termination and lay-off benefits rather than transferring them to these faraway locations for they would have to incur higher and heavier expenses in these various locations as the special circumstances of their families are such that it would not be expedient for their families to join them in these places.

[105] The Head of Human Resources should be explaining to the Industrial Court why the employees would all have to resign first before taking up the opportunity to be trained for 2 years by NAM, supposedly for them to be better equipped with knowledge and expertise in the field of Customer Satisfaction.

[106] Granted after the 2-year is up NAM may grant them employment if they are up to the mark set by NAM but then again there is the uncertainty of whether NAM is obligated to recognise their years of prior service with Perodua. If indeed after the 2-year period they are welcomed to return to Perodua then it begs the question as to why they must first resign. All these are fair questions that cry out for an explanation by the Company through its Head of Human Resources, who had come to the Industrial Court as its sole witness.

[107] All affected employees would want to know how the same need and opportunity for valuable training for the employees to upgrade their skills and to be internationally competent could not be achieved by the Company either seconding them or transferring them to NAM for a 2-year term and thereafter they may still opt to work for NAM if the terms of employment are no less favourable or to return to Perodua, with no question asked as Perodua had obligated itself to keeping their posts vacant for them. Of course, there is a catch and it is this: for so long as the vacancies are still there.

[108] Anything may happen after 2 years; the Company Perodua may want to outsource or transfer all their branches and service centres to NAM and so there would be no vacancies unless perhaps the employees are prepared to be transferred to faraway places like across the South China Sea to Sabah and Sarawak or to the east coasts of West Malaysia like in Kuala Terengganu. [109] The Company had not offered any reason why the employees should have these uncertainties hanging over their heads for 2 years; with them having to resign from Perodua and accepting a 2-year fixed term contract with the promise of re-employment back by Perodua but subject always to vacancies still being available.

[110] From the evidence adduced before the Industrial Court, the Company was bent on getting all employees to join NAM for a 2-year term for these Bukit Beruntung branch and Sungai Choh service centre. It was not a case of a valid option available to those who chose not to join whereas every encouragement is given for all to join NAM. At least the options must be clearly made known to the employees so that they can make an informed decision with no fear of unintended or collateral consequence of being transferred to some faraway locations. As was held by the Court of Appeal in Barat Estates Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Parawakan Subramanian & Ors [2000] 1 MLRA 404, compelling an employee to work for a particular employer, without affording him a choice in the matter, is merely another form of forced labour in violation of art 6 of the Federal Constitution.

[111] The Company must be clear and transparent in what had been painted as a transfer of its business in Bukit Beruntung and Sungai Choh to NAM. If it is a transfer of business, then it should be made clear that the Company does not have any vacancies left in Bukit Beruntung and Sungai Choh and that those who do not take up the offer would be paid termination and lay-off benefits or be transferred to faraway branches including to Kuala Terengganu, Kota Kinabalu and Kuching. See the Claimants' letter of 28 September 2017 at para 3 thereof at encl 8 PDF p 114.

[112] As it turned out to be, the 3 Claimants who did not take up the training for a 2-year term with NAM suffered a seismic shock in being served with a 3-day Notice of Transfer for them to report for duty at these 3 faraway locations. The whole Transfer exercise was tainted by a lack of transparency, smacked of mala fide and wholly unreasonable in the context and circumstances of the case and fell short of the contract test where "reasonableness" had been agreed by the Company to be a requirement of the Transfer exercise.

Decision

[113] The Industrial Court did not err in concluding that the Claimants had discharged their legal burden of proving constructive dismissal in a case where the Company had evinced its intention not to be bound by its very own term that it had introduced and imported into its contract with the Claimants.

[114] The Industrial Court had taken into consideration all the relevant factors and had not taken into consideration irrelevant factors, after having appreciated that the requirement of "reasonableness" was a term in the contract where Transfer was concerned. We are more than satisfied that the Industrial Court had acted according to equity, good conscience and the substantial merits of the case without regard to technicalities and legal form as mandated under s 30(5) of the IRA.

[115] We had therefore found merits in each of the 3 appeals and so we allowed all the 3 appeals and set aside the orders of the High Court. We reinstated the awards of the Industrial Court for each of the 3 Claimants/Appellants with costs of RM20,000.00 for each of the Appellants here and below subject to allocator.