Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Ahmad Zaidi Ibrahim, Hashim Hamzah, Faizah Jamaludin JJCA

[Civil Appeal Nos: W-02(NCvC)(W)-314-03-2023 & W-02(NCvC)(W)-116407-2023]

25 March 2025

Contract: Construction — Settlement agreement — Appeal against High Court's construction of terms of a settlement agreement — Whether phrase "to the Plaintiff" in settlement agreement required payment to be made directly to the plaintiff or could include payment to solicitor's client account — Whether High Court erred in relying on oral evidence to interpret written agreement — Whether Bank Negara Malaysia Claims Settlement Guidelines constituted a piece of subsidiary legislation with force of law and applied to payment by insurer — Whether solicitor's lien enforceable in absence of bill of costs and possession

These appeals ('Appeal 314' and 'Appeal 1164') arose from a Civil Suit in the High Court filed by the appellant following a dispute concerning performance of a settlement agreement in a prior medical negligence suit ('Suit 75'). Under the agreement, RM200,000.00 was to be paid by the three defendants to the plaintiff ('Rashid') in full and final settlement. The 1st defendant's insurer issued a cheque in favour of the plaintiff for RM145,000.00, representing his apportioned share. However, the plaintiff's solicitors, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, rejected the cheque, insisting payment be made to their client account. They subsequently returned all cheques, claiming the agreement had not been performed. The 1st defendant ('Dr Wahab') commenced Suit 281 seeking declarations that the settlement agreement was binding and had been complied with. The plaintiff ('Rashid') counterclaimed for general and exemplary damages and pre-judgment interest. The High Court held that the phrase "to the Plaintiff" in the settlement agreement included the plaintiff's solicitors, and ordered the settlement sum to be paid to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co's client account. It also dismissed the plaintiff's counterclaim for general and aggravated damages and pre-judgment interest. Both parties appealed.

Held (allowing Dr Wahab's Appeal 314 and dismissing Rashid's Appeal 1164):

(1) The phrase "to the Plaintiff" in the Settlement Agreement clearly referred to Rashid personally, not his solicitors. The High Court was plainly wrong in its interpretation and had no basis to expand the meaning to include the solicitor's client account. The construction of a contract was a question of law and ought to be resolved by reference to the objective intention of the parties using the plain and ordinary meaning of the language used. (paras 42, 50, 53 & 55)

(2) The High Court erred in relying on oral testimony to interpret the written agreement. Established principles dictated that courts must not admit parol evidence to vary or interpret the meaning of contractual terms unless ambiguity existed. (paras 57 & 60)

(3) The BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines, issued pursuant to the repealed Insurance Act 1996 and saved under the Financial Services Act 2013, constituted a piece of subsidiary legislation with the full force of law. The High Court erred in holding otherwise. Pursuant to these Guidelines, the Court found that the 1st defendant's insurer was obligated to make the settlement payment directly to Rashid. (paras 74, 78, 90 & 113)

(4) There was no valid solicitor's lien in law that could defeat payment directly to the plaintiff, as no bill of costs had been issued by Messrs. P.S. Ranjan & Co at the material time. A solicitor's lien being a possessory and passive right, could not be asserted without possession or a determined sum due. (paras 115, 130, 131 & 134)

Case(s) referred to:

Affin Bank Bhd v. Datuk Ahmad Zahid Hamidi [2005] 1 MLRH 64 (refd)

Bahamas International Trust Co Ltd v. Threadgold [1974] 1 WLR 1514 (refd)

Barrat v. Gough Thomas [1950] 2 All ER 1048 (refd)

Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd [2009] 3 MLRA 1 (refd)

Development & Commercial Bank Bhd v. Cheah Theam Swee [1989] 1 MLRH 332(refd)

Diana Chee Vun Hsai v. Citibank Bhd [2009] 1 MLRH 881 (refd)

Dream Property Sdn Bhd v. Atlas Housing Sdn Bhd [2015] 2 MLRA 247 (refd)

Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1 (refd)

Lucy Wong Nyuk King & Anor v. Hwang Mee Hiong [2016] 3 MLRA 367 (refd)

M Wealth Corridor Sdn Bhd v. Chan Tse Yuen & Co [2018] 4 MLRH 256 (refd)

Messrs Roland Cheng & Co v. Konkamaju Sdn Bhd [2013] 7 MLRA 101 (refd)

Nabors Drilling (Labuan) Corporation v. Lembaga Perkhidmatan Kewangan Labuan [2018] 2 SSLR 201 (refd)

Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 (refd)

Nvj Menon v. The Great Eastern Life Assurance Company Ltd [2002] 2 MLRA 510 (refd)

Silver Concept Sdn Bhd v. Brisdale Rasa Development Sdn Bhd [2005] 1 MLRA 463(refd)

Tan Sri Datuk Nadraja Ratnam v. Murali Subramaniam [2017] MLRHU 1832 (refd)

Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Tekali Prospecting Sdn Bhd [2002] 1 MLRA 351 (refd)

Uem Group Bhd v. Genisys Integrated Engineers Pte Ltd & Anor [2010] 2 MLRA 668(refd)

V Manuel v. Omar Bin Haji Ahmad & Ors [1974] 1 MLRA 192 (refd)

Wong Yee Boon v. Gainvest Builders (M) Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 MLRA 481 (refd)

Yii Ming Tung v. PP [2015] 2 MLRA 227 (refd)

Zulpadli & Edham v. Inai Offshore & Marine Engineering Sdn Bhd [2011] 2 MLRA 101 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989, s 6(4)

Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009, ss 3, 5(1), (2), (3), 95

Financial Services Act 2013, ss 2, 7(1), (2), 10, 23(4)(d), 236, 234(1)( d), (3)(a),(b), (c), (d), (e), (4)(d), (6), (9), (10), 239, 240(1), 272(b), (m),273(1)( a)

Insurance Act 1996, ss 16, 201

Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967, ss 2, 3

Labuan Financial Services Authority Act 1996, s 4A

Legal Profession Act 1976, s 78(1), (2)

Rules of Court 2012, O 22B rr 1, 8

Solicitors' Account Rules 1990, r 7(a)(v)

Counsel:

[Civil Appeal Nos: W-02(NCvC)(W)-314-03-2023]

For the appellant: Ambiga Sreenevasan (Tan Keng Teck,Ung Zhee Laine Einel & Anishaa Sundramoorthy with him); M/s Lim Kian Leong & Co

For the 1st respondent: T Gunaseelan (Kailesh Arumugam & Kumaradevan Rajadevan with him); M/s Kailesh Aru & Co

For the 2nd respondent: Thinesh Bathmala; M/s Raja, Darryl & Loh

For the 3rd respondent: Balakumar Balasundram (Wong Ik Ling with him); M/s Azim,Tunku Farik & Wong

[Civil Appeal Nos: W-02(NCvC)(W)-1164-07-2023]

For the appellant: T Gunaseelan (Kailesh Arumugam & Kumaradevan Rajadevan with him); M/s Kailesh Aru & Co

For the 1st respondent: Ambiga Sreenevasan (Tan Keng Teck, Ung Zhee Laine Einel & Anishaa Sundramoorthy with him); M/s Lim Kian Leong & Co

For the 2nd respondent: Thinesh Bathmala; M/s Raja, Darryl & Loh

For the 3rd respondent: Balakumar Balasundram (Wong Ik Ling with him); M/s Azim, Tunku Farik & Wong

[For the High Court judgment, please refer to Dato Dr Abd Wahab Abd Ghani lwn. Mohd Rashid Mohd Noor & Yang Lain [2023] MLRHU 999]

JUDGMENT

Faizah Jamaludin JCA:

Introduction

[1] Both these appeals before us — Civil Appeal No W-02(NCVC)(W)-314-03/2023 ("Appeal 314") and W-02(NCVC)(W)-1164-07/2023 ("Appeal 1164") — arose from the Kuala Lumpur High Court Civil Suit No: WA-22NCVC-281 -05/2018 ("Suit 281").

[2] Suit 281 in turn arose from a settlement agreement ("Settlement Agreement") entered between the same parties in Civil Suit No: WA- 22NCVC-75-02/2016 ("Suit 75"). These appeals primarily revolve around the construction and interpretation of the Settlement Agreement and the words "to the Plaintiff' in the Agreement.

[3] Suit 75 was a medical negligence action brought by the plaintiff, Mohd Rashid bin Mohd Noor ("Rashid") against the 1st defendant, Dato' Dr Abd Wahab bin Abd Ghani ("Dr Wahab"), the 2nd defendant, Dr Arul Balasingam ("Dr Arul") and the 3rd defendant, Ampang Puteri Specialist Hospital Sdn Bhd ("the Hospital").

[4] Appeal 314 was brought by Dr Wahab, who was the plaintiff in the main suit and the 1st defendant in the counterclaim in Suit 281. Appeal 1164 was brought by Rashid, who was the 1st defendant in the main suit and the plaintiff in the counterclaim in Suit 281. Dr Arul and the Hospital were brought in as nominal respondents in both these appeals.

[5] Dr Wahab's appeal in Appeal 314 is principally against the High Court's order directing that the Settlement Sum be paid to the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co. It also contests the findings of the High Court that (i) the phrase "to the Plaintiff' in the Settlement Agreement also refers to "Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co", and (ii) the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines (defined below) are mere guidelines and do not carry the force of law.

[6] Whereas Rashid's appeal in Appeal 1164 is against the dismissal of the High Court of part of his counterclaim for pre-judgment interest on the Settlement Sum and for general damages and exemplary damages, as well as cost of RM30,000.00 awarded to him by High Court.

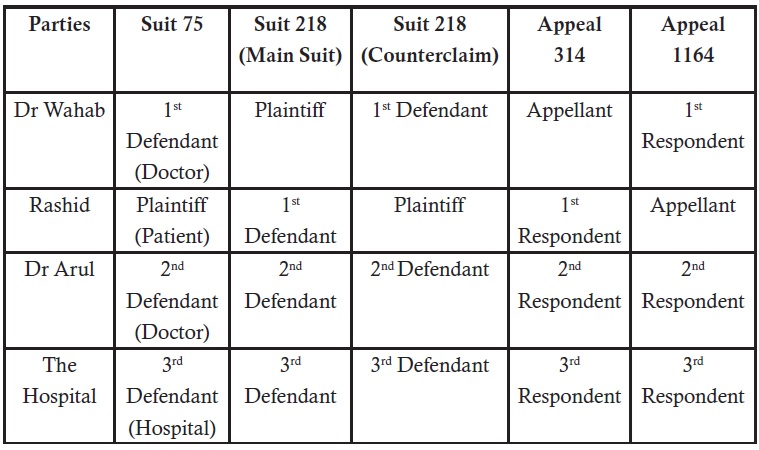

[7] The parties in Suit 75, Suit 281, Appeal 314 and Appeal 1164 are detailed in the table below:

[8] Having considered the appeal records and the submissions of parties, we unanimously decided that Appeal 314 was with merit and Appeal 1164 was without merit. We, accordingly, allowed Appeal 314 and dismissed Appeal 1164.

[9] The reasons for our decision are set out in full hereinafter.

Key Background Facts

The Settlement Agreement in Suit 75

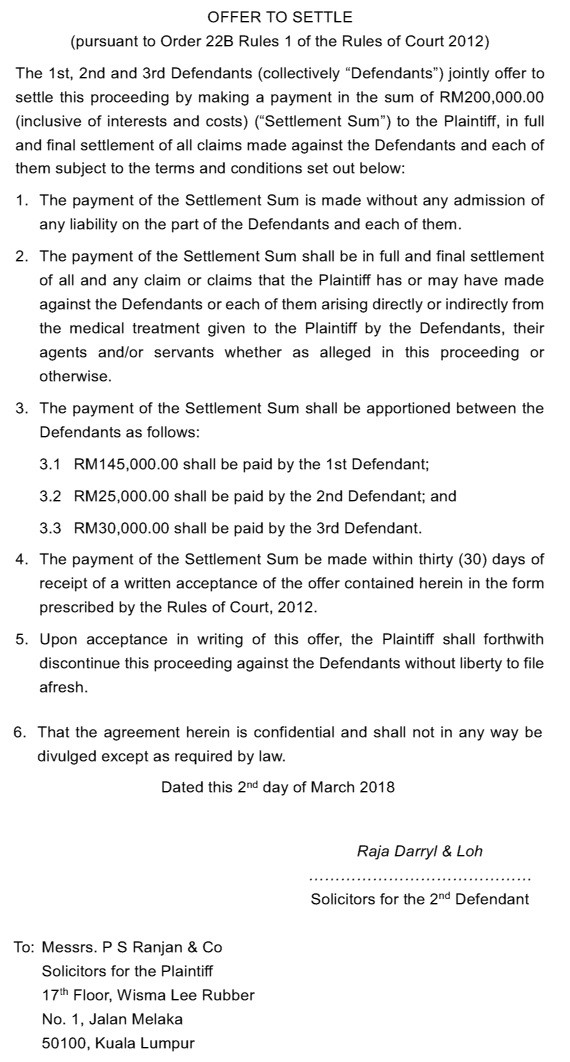

[10] The parties agreed in the Settlement Agreement that the defendants will pay "to the Plaintiff' the sum of RM 200,000.00 ("Settlement Sum") in full and final settlement of Suit 75. Dr Wahab's portion of the Settlement Sum was RM 145,000.00, Dr Arul's was RM 25,000.00, and the Hospital's was RM 30,000.00.

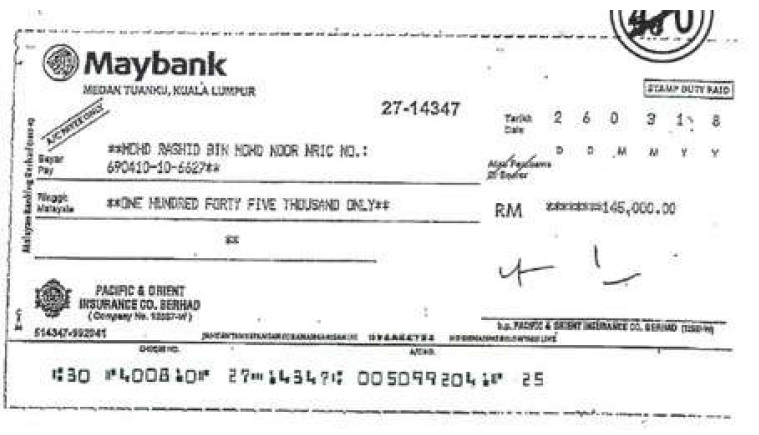

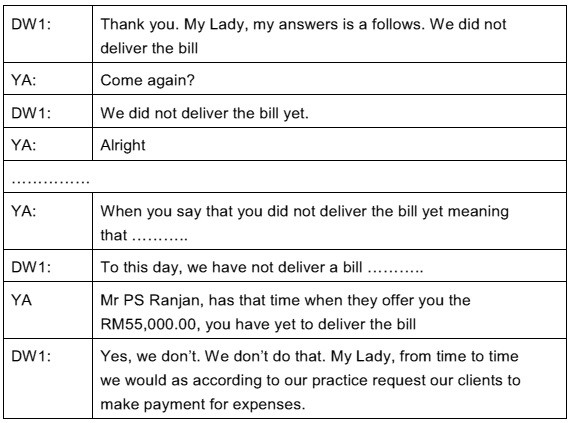

[11] Pacific & Orient Insurance Company Berhad ("P&O Insurance"), who is Dr Wahab's insurer, issued a cheque ("P&O Cheque") in favour of Rashid for the sum of RM 145,000.00. Whereas Dr Arul's and the Hospital's insurers each issued cheques for the sum of RM 25,000.00 and RM 30,000.00 respectively in favour of "P.S. Ranjan & Co Advocates & Solicitors — Client Account'. An image of the P&O Cheque is reproduced below:

[12] Dr Wahab's solicitors, Messrs Low Aljafri & Associates ("Messrs Low Aljafri") delivered the P&O cheque to the Rashid's solicitors, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co on 2 April 2018.

[13] On the same day it received the P&O cheque, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co returned the cheque to Messrs Low Aljafri because the cheque was not made in favour of "Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co Advocates & Solicitors - Client Account". Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co also, on the same day, informed the solicitors acting for Dr Arul and the Hospital that if Dr Wahab's solicitors do not deliver within time "a cheque in our favour for the sum of RM145,000.00" it will not accept any payment from Dr Arul and the Hospital with regards to the settlement.

[14] Messrs Low Aljafri re-delivered the P&O cheque to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co on 4 April 2018.

[15] On 11 April 2018, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co again returned the P&O cheque to Messrs Low Aljafri. It also returned the cheques issued by Dr Arul's and the Hospital's respective insurers to their respective solicitors. In its letter dated 11 April 2018 to Dr Arul's and the Hospital's solicitors, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co stated, inter alia, that the Settlement Agreement had not been performed because Dr Wahab had not made payment of his portion of the Settlement Sum in cash or in a cheque in Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co's favour.

Suit 281

[16] On 16 May 2018, Dr Wahab commenced Suit 281 at the Kuala Lumpur High Court seeking, inter alia, declarations that the Settlement Agreement constitutes a binding agreement and that all parties to Suit 75 are bound by it; and the Settlement Sum be paid to Rashid himself. Dr Wahab also sought for an order to compel Rashid to accept payment of the Settlement Sum as apportioned in the Settlement Agreement.

[17] Dr Wahab was the plaintiff and Rashid was the 1st defendant in Suit 281. Dr Arul and the Hospital were made nominal defendants in Suit 281.

[18] Rashid in his counterclaim in Suit 281 sought, among others, judgment against Dr Wahab, Dr Arul and the Hospital for the sum of RM 200,000.00, damages, pre-judgment interest from 4 April 2018 at the rate of 8% per annum, and post-judgment interest at the rate of 5%.

[19] The trial of Suit 281 took place over 3 days. Two witnesses testified on behalf of Dr Wahab and three witnesses on behalf of Rashid.

[20] Below are the key findings the High Court Judge:

(i) The Settlement Agreement constituted a binding agreement and on all parties in Suit 75 are bound by the Agreement;

(ii) The meaning of the words "to the Plaintiff' in the Settlement Agreement also refers "to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co"; and

(iii) The BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines (defined below) issued by Bank Negara Malaysia are mere guidelines and do not have the force of law.

[21] Premised on these findings, the High Court on 30 January 2023 made the following Orders:

(i) A declaration that the Settlement Agreement constituted a binding agreement and parties in Suit 75 are bound by the Agreement;

(ii) The Settlement Sum of RM200,000.00 be paid to the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co;

(iii) Dr Wahab to pay interest at the rate of 5% on RM200,000.00 from the date of judgment until date of resolution; and

(iv) Costs of RM30,000.00 to be paid by Dr Wahab to Rashid and costs of RM15,000.00 each to be paid by Dr Wahab to Dr Arul and the Hospital.

Appeal 314 and Appeal 1164

[22] Both Dr Wahab and Rashid were dissatisfied with the findings and judgment of the High Court in Suit 281. They each appealed against part of the judgment: Dr Wahab filed Appeal 314 and Rashid filed Appeal 1164.

[23] Dr Wahab's appeal in Appeal 314 is against part of the High Court judgment that ordered:

(a) the settlement sum of RM200,000.00 to the 1st defendant (Rashid) be paid to the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co;

(b) Interest at the rate of 5% on the sum of RM200,000.00 be paid by Dr Wahab to Rashid from the date of Judgment until settlement;

(c) costs to be paid by Dr Wahab to Rashid in the sum of RM30,000.00; to Dr Arul in the sum of RM15,000.00; and the Hospital in the sum of RM15,000.00.

[24] Rashid's appeal in Appeal 1164 is against part of the High Court judgment that:

I. dismissed his counterclaim for pre-judgment interest on the sum of RM200,000.00;

II. dismissed of his counterclaim for general damages and aggravated damages; and

III. awarded costs in the sum of only RM30,000.00 to him.

[25] Dr Arul and the Hospital are nominal respondents in these appeals. They oppose both appeals, inter alia, on the grounds that (i) the Settlement Agreement expressly provided for several liability on the part of Dr Wahab, Dr Arul and the Hospital; and (ii) they had both paid their respective portions of the Settlement Sum to Rashid and/or Rashid's solicitors (Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co) within the time stipulated in Settlement Agreement.

[26] Dr Wahab did not raise any grounds of appeal against Dr Arul and the Hospital in his memorandum of appeal and Supplementary memorandum of appeals.

[27] Dr Wahab and Rashid each filed joint written submissions for Appeal 314 and Appeal 1164.

Dr Wahab's Case

[28] Learned counsel for Dr Wahab submitted that the core issues in these Appeals are:

4. The dispute in these Appeals is centered around the issue of to whom payment of the settlement sum valued at RM200,000.00 (Settlement Sum) should be made pursuant to the Settlement Agreement (defined below). Crucially, whether the Settlement Sum is to be paid directly to Rashid or to Rashid' solicitors in Suit 75 (defined below, Messrs P S Ranjan & Co).

5. We submit that the core questions before this Honourable Court are:

5.1 Whether Dr Wahab has acted in accordance with the Settlement Agreement, read in its natural and ordinary meaning;

5.2 In the circumstances where there has been no agreement between the parties to vary the terms of the Settlement Agreement, can Dr Wahab be compelled and/or ordered to act in a manner contrary to the terms of the Settlement Agreement?

5.3 In circumstances where Rashid has accepted the payment term whereby payment is to be made to Rashid, can Rashid or his solicitors refuse payment to be made to Rashid?

[29] In Appeal 314, learned counsel for Dr Wahab submitted that the High Court was in error in holding that the meaning of the words "to the Plaintiff' in the Settlement Agreement also refers to "Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co". He submitted the High Court's finding goes against the natural and ordinary meaning of the terms in the Settlement Agreement and against settled legal principles of construction and interpretation of contracts. Dr Wahab's counsel argued that the High Court had effectively re-written the terms of the Settlement Agreement by ordering payment to the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co.

[30] Further, he submitted that the High Court was plainly wrong in finding that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines were mere guidelines which did not have the force of law. He argued that based on the applicable statutes and case law, the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are a piece of subsidiary legislation that have a force of law. The BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines states at para 4.4.4.1 that "full payment must be made to the claimant'. Dr Wahab's counsel submitted that para 4.4.4.1 of the Guidelines should, on the facts of Suit 75, be construed to refer to Rashid — the plaintiff in Suit 75 who is claiming against Dr Wahab's insurance policy.

[31] Dr Wahab submitted that the payment of his portion of the Settlement Sum through a cheque in favour of Rashid was in accordance with the express term of the Settlement Agreement and the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines.

Rashid's Case

[32] Although Rashid's appeal in Appeal 1164 is in relation to the dismissal of his counterclaim for pre-judgment interest, damages and costs, learned counsel for Rashid submitted the issues in these Appeals are whether Dr Wahab (i) can refuse to recognise the authority given by law for Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co to receive payment on behalf of its client, Rashid, and (ii) ignore Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co's lien for their costs and make payment directly to Rashid. Para 11 of the written submissions of Rashid's counsel is reproduced below:

11. The dispute is essentially about these issues which had been decided in favour of Encik Rashid by the High Court:

5.1 whether, following the settlement, Dato' Abd Wahab can properly and lawfully refuse to recognise Encik Rashid's solicitors Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co's authority given by law to receive payment on behalf of their client; and

5.2 whether Dato' Abd Wahab has the right to ignore Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co's solicitors' lien for their costs and make payment directly to Encik Rashid.

[33] Learned counsel for Rashid submitted by paying the RM145,000.00 through a cheque in favour of Rashid — instead of one in favour of the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, Dr Wahab, his insurer and solicitors were seeking to challenge the concept of solicitor's lien and the authority of solicitors to receive monies on behalf of their clients.

[34] Rashid's counsel further submitted that if these Appeals are decided in favour of Dr Wahab the result will be that insurance companies acting for defendants in personal injury cases could severely undermine the solicitors' lien of the solicitors for the Plaintiff.

Issues

[35] Based on the records of appeals and the submission of parties, the issues for this Court's determination in Appeal 314 and Appeal 1164 are:

I. What did the parties in Suit 75 agree in the Settlement Agreement?

II. Do the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines have the force of law? and

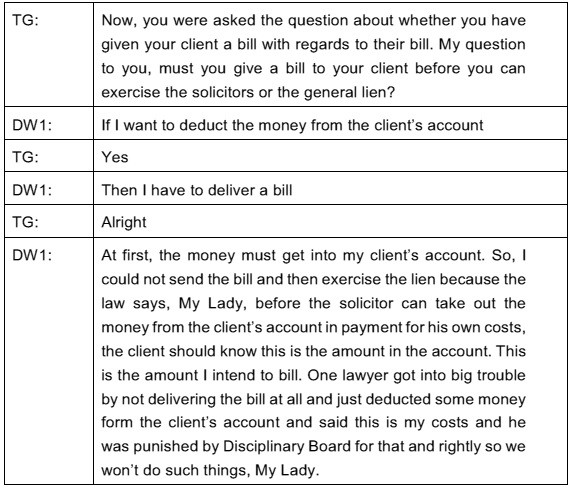

III. By making the payment cheque for the Settlement Sum in favour of the Plaintiff, did Dr Wahab and/or his insurer: (a) refuse to recognise the authority given by law for a solicitor to receive payment on behalf of their client, or (b) ignore a solicitor's lien on costs owed by their client?

Principles Of Appelate Intervention

[36] The law is settled that an appellate court ought not to disturb the trial court's conclusion on primary facts unless it is satisfied the trial Judge was plainly wrong. Based on this "plainly wrong test", an appellate court is entitled to examine the process of evaluation of evidence by the trial court and may set aside any decision of the trial court with no or insufficient judicial appreciation of the evidence or based on errors of law: see the Federal Court decisions in Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1; UEM Group Berhad v. Genisys Integrated Engineers Pte Ltd [2010] 2 MLRA 668; Dream Property Sdn Bhd v. Atlas Housing Sdn Bhd [2015] 2 MLRA 247; Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Pen, Administrator Of The Estates Of Tan Ewe Kwang, Deceased & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193.

[37] Therefore, in deciding whether this Court should interfere with the decision made by the High Court in Suit 281, this Court has to ascertain whether the learned Judge was plainly wrong based on the facts of this case and the applicable law.

E. Analysis And Findings Of This Court

Issue (I) What Did The Parties In Suit 75 Agree To In The Settlement Agreement?

[38] It is a well-established legal principle that the construction and interpretation of a contract is a question of law to be determined by the Courts, as held by this Court in Silver Concept Sdn Bhd v. Brisdale Rasa Development Sdn Bhd [2005] 1 MLRA 463.

[39] In addressing Issue (I), this Court is obligated to give effect to the intention of the parties to the Settlement Agreement. To achieve this, it is necessary for us to construe and interpret the terms of the Settlement Agreement in accordance with the following legal principles:

(a) In construing a contract, courts must give effect to the intention of the parties by looking at the contract as whole. It should adopt an objective approach and interpret the words in their natural and ordinary sense: see Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd [2009] 3 MLRA 1; Lucy Wong Nyuk King & Anor v. Hwang Mee Hiong [2016] 3 MLRA 367; Wong Yee Boon v. Gainvest Builders (M) Sdn Bhd [2020] 1 MLRA 481;

(b) In interpreting a private contract, courts are entitled to look at the factual matrix forming the background to the transaction: Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd [2009] 3 MLRA 1;

(c) Courts are not bound by the testimony of witnesses or concessions made by counsel: NVJ Menon v. The Great Eastern Life Assurance Company Ltd [2002] 2 MLRA 510; Silver Concept Sdn Bhd v. Brisdale Rasa Development Sdn Bhd (supra); and

(d) Courts do not have the power to improve on an instrument that it is called upon to construe. It cannot introduce terms to make it fairer or more reasonable. It is concerned only to discover what the instrument means: Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd (supra) citing with approval the statement made by Lord Hoffman in Attorney General of Belize v. Belize Telecom Limited [2009] UKPC 11.

[40] The Settlement Agreement is a contract entered between the plaintiff (Rashid) and the defendants (Dr Wahab, Dr Arul and Ampang Puteri Hospital) in full and final settlement of the plaintiff's action for medical negligence against the defendants in Suit 75. The Settlement Agreement expressly states that the defendants are to pay the Settlement Sum of RM200,000.00 "to the Plaintiff'.

[41] Based on the aforementioned principals of construction and interpretation of contracts, this Court in construing in the meaning of the words "to the Plaintiff in the Settlement Agreement, must do so objectively and give the words its natural and ordinary meaning.

[42] Taking an objective view of the contract as a whole — within the four corners of the Settlement Agreement, we find that the phrase "to the Plaintiff' in its natural and ordinary meaning, refers the plaintiff in Suit 75, who is Rashid. Thus, we conclude that the intention of the parties to the Settlement Agreement was for the Settlement Sum to be paid to Rashid in full and final settlement of his claim in Suit 75 against the defendants.

[43] However, in interpreting the Settlement Agreement we are not strictly confined to its four corners. Courts, in construing a private contract, are entitled to examine the factual matrix forming the background to the contract, as demonstrated in Berjaya Times Square Sdn Bhd v. M-Concept Sdn Bhd (supra) where Gopal Sri Ram FCJ delivering the judgment of the Federal Court, stated:

[42] Here it is important to bear in mind that a contract is to be interpreted in accordance with the following guidelines. First, a court interpreting a private contract is not confined to the four corners of the document. It is entitled to look at the factual matrix forming the background to the transaction. Second, the factual matrix which forms the background to the transaction includes all material that was reasonably available to the parties. Third, the interpreting court must disregard any part of the background that is declaratory of subjective intent only. Lastly, the court should adopt an objective approach when interpreting a private contract.

[Emphasis added]

[44] Accordingly, we have also considered the factual matrix forming the background of the Settlement Agreement to objectively determine whether a different interpretation, particularly of the words "to the Plaintiff' in the Agreement, might be reached.

[45] As outlined in the Introduction section of this judgment, the Settlement Agreement was entered between the plaintiff and the defendants in Suit 75. This was a suit for medical negligence brought by the plaintiff, Rashid, who was the patient, against the Dr Wahab and Dr Arul, as the 1st and 2nd defendants respectively, and the Hospital, as the 3rd defendant.

[46] During the course of Suit 75, the defendants jointly made an Offer to Settle, pursuant to O 22B r 1 of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC"). It was made in Form 34 of the ROC. The Offer to Settle dated 2 March 2018 was filed in Court by Messrs Raja Darryl & Loh, the solicitors of the 2nd defendant (Dr Arul) and served on Messrs P. S. Ranjan & Co, solicitors of the plaintiff (Rashid). The Offer to Settle is reproduced below:

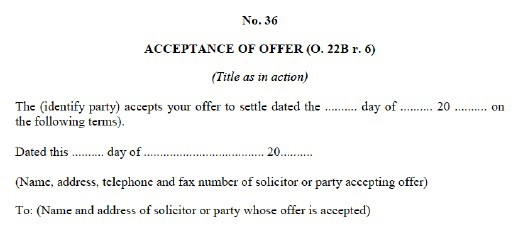

[47] The Offer to Settle was accepted by the plaintiff in an Acceptance of Offer (pursuant to O 22B r 8 of the ROC) dated 5 March 2018. The Acceptance of Offer is reproduced below:

[48] The Acceptance of the Offer was made by the plaintiff in Form 36 of the ROC. Form 36 is reproduced below:

[49] As reflected in Form 36, a plaintiff may state that he accepts the offer to settle on specific terms detailed on the Acceptance of Offer. The terms, could for instance, include the Settlement Sum to be paid to the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co. However, in this case, Rashid did not specify any terms when accepting the defendants' Offer to Settle. His Acceptance of Offer simply stated, "The Plaintiff accepts your offer to settle dated 2 March 2018".

[50] After objectively examining the factual matrix leading to the Settlement Agreement, our interpretation remains unchanged: the Settlement Sum is to be paid directly to the plaintiff, Rashid. To interpret the phrase "to the Plaintiff" as including anyone other than Rashid would represent an unwarranted distortion of the plain and ordinary meaning of the words in the Settlement Agreement.

[51] Furthermore, in cases where an agreement has been professionally drafted, there is limited scope for parties to deviate from a textual analysis of its terms In Silver Concept Sdn Bhd v. Brisdale Rasa Development Sdn Bhd [2005] 1 MLRA 463, this Court held that the respondent could not resile from the undertaking given to the appellant. This conclusion was grounded on three key factors: (i) the words in undertaking are plain, clear and unambiguous; (ii) both parties had legal representation during the drafting of the agreement, and (iii) the respondent gave the express undertaking with the benefit of legal advice.

[52] Similarly, in this present case, (i) the language in the Settlement Agreement, the Offer to Settle and the Acceptance of Offer is plain, clear and unambiguous; (ii) the plaintiff and the defendants in Suit 75 had legal representation; (iii) the defendants' Offer to Settle and the plaintiff's Acceptance of Offer were professionally drafted by their respective solicitors; and (iv) Rashid had accepted the Offer to Settle with the benefit of legal advice from his solicitors. Accordingly, Rashid cannot withdraw from the agreement established in the Settlement Agreement, which stipulates that the Settlement Sum is to be paid by the defendants to the plaintiff in Suit 75.

[53] The learned High Court Judge found that the words "to the Plaintiff" in the Settlement Agreement also refer to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co as Rashid's solicitors, and that it is apt for the RM145,000.00 (ie Dr Wahab's portion of the Settlement Sum) to be paid to the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co Her Ladyship stated in para 66 of the High Court's grounds of judgment ("GOJ"):

[66] Mahkamah berpendapat bahawa perkataan "to the Plaintiff" juga merujuk kepada Tetuan P.S. Ranjan sebagai peguamcara Defendan Pertama maka adalah sewajarnya wang RM145,000.00 dibayar kepada akaun pelanggan peguamcara Tetuan P.S. Ranjan.

[54] Her Ladyship's reasons for such finding as can be gathered from her grounds of judgment are:

(i) The BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are merely guidelines without the force of law: see paras 59, 61, and 72 of the GOJ;

(ii) It is more appropriate that the Settlement Sum be paid to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co who had represented Rashid in Suit 75, taking into consideration that there are costs that must be paid by Rashid to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co: see para 66 of the GOJ;

(iii) Rashid himself testified during the trial that the cheque should be made in the name of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co: see para 65 of the GOJ; and

(iv) Referring to the case of Tan Sri Datuk Nadraja Ratnam v. Murali Subramaniam [2017] MLRHU 1832, as Rashid was represented by solicitors, there is no reason why payment should be made to Rashid: see paras 67 and 68 of the GOJ.

[55] With due respect to the learned High Court Judge, we cannot concur with her finding that the words "to the Plaintiff" also refer Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co From our objective standpoint, this interpretation contradicts the natural and ordinary meaning of the term "Plaintiff'. Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co was not the plaintiff in Suit 75 — Rashid was. Furthermore, this interpretation deviates from established principles of contract construction and interpretation consistently upheld by the Federal Court and Court of Appeal.

[56] Additionally, the High Court erred in considering Rashid's testimony when interpreting the words "to the Plaintiff' in the Settlement Agreement. The High Court in para 65 of the GOJ stated:

"[65] Mahkamah juga menekankan bahawa Defendan Pertama sendiri dalam keterangannya mengatakan bahawa sepatutnya cek tersebut dibuat diatas nama P.S. Ranjan & Co Mahkamah merujuk kepada keterengan beliau dalam Mahkamah seperti berikut: ........."

[57] As established by this Court in NVJ Menon v. The Great Eastern Life Assurance Company Ltd [2002] 2 MLRA 510 and Silver Concept Sdn Bhd v. Brisdale Rasa Development Sdn Bhd (supra), when construing a contract, Courts should not consider the oral evidence of witnesses presented at trial regarding the meaning and interpretation of contract between the parties. Furthermore, Courts are not bound by the testimony of witnesses or concessions made by counsel. Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as he then was) delivering the judgment of this Court in NVJ Menon v. The Great Eastern Life Assurance Co Ltd [2002] 2 MLRA 510 said:

"It would be noticed that we have in arriving at our aforesaid conclusion made no reference to the oral evidence led at the trial as to the meaning and interpretation of the contract between the parties. This is because the construction of a contract is a question of law for determination by the court and not by witnesses through their oral evidence.

.................

So too here. It matters not a jot to us what the plaintiff thought his entitlements under the contract with the defendant were. Neither does it matter to us what the defendant's witnesses thought of the way in which that contract ought to be interpreted. Their views are entirely irrelevant; as irrelevant as the views of the witnesses who gave their interpretation of the Financial Orders in Reynolds.

In the instant case, the learned judge referred to the oral testimony and relied upon it for the interpretation of the agreements and circulars. That, in our view is clearly an inadmissible method of construction.

.................

[Emphasis added]

[58] And in Silver Concept Sdn Bhd v. Brisdale Rasa Development Sdn Bhd, Abdul Kadir Sulaiman JCA delivering the judgment of this Court said:

The construction of a contract is a question of law to be determined by this court. This court is not bound by the admission of witnesses or the concession made by counsel in the court below.

[Emphasis added]

[59] This Court, in both NVJ Menon and Silver Concept, quoted with approval Lord Diplock's observation in Bahamas International Trust Co Ltd v. Threadgold [1974] 1 WLR 1514, where he said:

In a case which turns, as this one does, on the construction to be given to a written document, a court called on to construe the document in the absence of any claim to rectification, cannot be bound by any concession made by any of the parties as to what its language means. That is so even in the court before which the concession is made; a fortiori in the court to which an appeal from the judgment of the court is brought. The reason is that the construction of a written document is a question of law. It is for the judge to decide for himself what the law is, not to accept it from any or even all of the parties to the suit; having so decided it is his duty to apply it to the facts of the case. He would be acting contrary to his judicial oath if he were to determine the case by applying what the parties conceived to be the law, if in his own opinion it were erroneous.

[Emphasis added]

[60] In this case, the High Court by considering Rashid's oral testimony to interpret the words "to the Plaintiff" in the Settlement Agreement, disregarded established principles of contractual interpretation and construction. Furthermore, this approach, contrary to the doctrine of stare decisis, failed to uphold the precedents set by this Court in NVJ Menon and Silver Concept on the matter.

[61] The High Court referred to the case of Tan Sri Datuk Nadraja Ratnam v. Murali Subramaniam [2017] MLRHU 1832 and held that because Rashid is represented by solicitors, there is no reason why payment of the Settlement Sum was made to Rashid by the insurers.

[62] The Nadaraja case relates to conditional stay of execution order by the High Court dated 15 February 2017, where the Court agreed to stay the execution of its judgment against the defendant pending the disposal of the defendant's appeal at the Court of Appeal, on the condition that the defendant pay the sum of RM50,000.00 on or before 8 March 2017. Even though the High Court in Nadaraja did not order the RM50,000.00 be paid to the plaintiff, the plaintiff's solicitors had added the words "kepada plaintif in the draft order, which was not objected to by the defendant's solicitors. The stay order was sealed by the Court based on the draft order. Nantha Balan J (as he then was) in his judgment said:

"[38] to the extent that the stay order states that the monies are to be paid to the plaintiff, it is true that this was not reflected in the notes of proceedings. Rather it was inserted into the order by the plaintiff's solicitors and not objected to by the defendant's erstwhile solicitors".

[63] On 8 March 2017, the defendant tried to pay the sum of RM50,000.00 in cash to the plaintiff's solicitors but they refused to accept the payment on the basis that the sealed Order states that the payment was made "kepada plaintif". The solicitors said that they had no instructions from the plaintiff to accept the payment. The defendant then tried to make the payment directly to the plaintiff: he looked for the plaintiff at his residential address and two Hindu temples under the plaintiff's jurisdiction but the plaintiff could not be found. The defendant then paid the sum of RM50,000.00 by cheque into Court the next day on 9 March 2017. The plaintiff claimed that the stay order had lapsed because the defendant had not paid the RM50,000.00 by 8 March 2017 as ordered by the High Court. The defendant then filed an application to amend the stay order under the slip rule, and another application to vary the order by deleting the words "kepada plaintif" that was inserted by the plaintiff's solicitors in the order.

[64] It was in that context that Nantha Balan J (as he then was) said in his judgment that he was baffled by the stance taken by the plaintiff's solicitors when they refused to take the payment of the RM50,000.00 from the defendant since at law, the plaintiff's solicitors were his agents and had the requisite legal authority to accept the sum of RM50,000.00 on the plaintiff's behalf.

[65] His Lordship did not say the payment of the RM50,000.00 could not be made to the plaintiff directly. What he said was:

"[28] there is no difference whether payment is made by the plaintiff or his solicitor. Indeed, it is unusual for party to be dealing directly with the other side when there are solicitors acting for both sides."

[66] In this instant case, Dr Wahab's solicitors did not deal directly with Rashid. At all times, Messrs Low Aljafri dealt directly with Rashid's solicitors, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co. Not once did they deliver the P&O Cheque directly to Rashid, even after the P&O Cheque was rejected twice by Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co.

[67] Also, nowhere in the judgment in Nadaraja did the High Court hold that payment "to the plaintiff is equivalent to "payment in favour of the solicitor client account of the plaintiff's solicitors". It also did not hold that the word "to the Plaintiff' also refers to "the Plaintiff's solicitors".

[68] What the High Court in Nadaraja held was that the plaintiff's solicitor, as its client's agent, may and ought to have accepted on behalf of the plaintiff, the payment in cash of RM50,000.00 by the defendant. It also held that the cheque for the sum of RM50,000.00 paid by the defendant into Court was good for payment, as can be seen from the excerpt of para 28 of the judgment, where Nantha Balan J said:

"[28] ...and as he did pay a cheque of RM50,000.00 (which was good for payment) into Court the next day..."

Findings on Issue (I)

[69] For the reasons above, we find that the plaintiff and the defendants in Suit 75 agreed in the Settlement Agreement that the Settlement Sum of RM200,000.00 be paid to Rashid in full and final settlement of his claims against the defendants in Suit 75.

[70] Based on the settled principles of construction and interpretation of contracts, we find that the High Court was plainly wrong to hold that the word "to the Plaintiff' in the Settlement Agreement also refers "to Messrs P.S. Ranjan".

[71] Accordingly, we further find that the High Court was plainly wrong to order that payment of the Settlement Sum be made to the client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co.

Issue (II): Do the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines Have The Force Of Law?

[72] The second issue before us is whether the Claims Settlement Practices (Consolidated) [BNM/RH/GL/0003-9] ("BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines") issued by Bank Negara Malaysia ("BNM") on 5 October 2006 pursuant to s 201 of the Insurance Act 1996 (Act 553) ("IA 1996") have the force of law and are legally binding. Or are they mere guidelines as held by the High Court in this instant case?

[73] Para 2.1 of the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines expressly stipulates that the Guidelines must be observed by insurance companies and loss adjusters in relation to their general insurance business with immediate effect. It also stipulates in para 4.4.4.1 that "full payment must be made to the claimant".

[74] Learned counsel for Dr Wahab submitted that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are legally binding and have the force of law. Rashid is the claimant against Dr Wahab's insurance policy with P&O Insurance. Therefore, P&O Insurance is compelled under the terms of the BNM Guidelines to make the settlement payment to Rashid.

[75] Whereas, learned counsel for Rashid submitted because the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines were issued under the now repealed IA 1996, it is no longer good reference. He further submitted that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are mere guidelines, which do not have any force of law and are accordingly not binding on the insurers, the legal profession and the Courts.

[76] The High Court agreed with the position submitted by Rashid's counsel. The learned High Court Judge held that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are mere guidelines and not statutory law. She held that the said Guidelines are not legally binding on the parties since it does not have the force of law. Therefore, the Settlement Sum should be paid by the insurers to Rashid through the solicitors and client account of Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co. Her Ladyship said in her GOJ:

"[59] Mahkamah berpendapat Garis Panduan BNM hanyalah garis panduan dan bukannya undang-undang statutory yang mengikat pihak-pihak di sisi undang-undang kerana ia tidak mempunyai kuasa undang-undang yang boleh memaksa pematuhan.

[61] Mahkamah berpandangan bahawa Garis Panduan BNM adalah garis panduan yang tidak ada kuasa untuk memaksa peguamcara untuk digunakan seperti undang-undang bertulis. Dan tidak sepatutunya garispanduan dibaca seumpama setaraf dengan undang-undang. Lebih-lebih lagi dalam keadaan dimana ia akan memprejudiskan pihak-pihak.

[72] Mahkamah juga berpendapat bahawa Garis Panduan BNM adalah sebagai panduan semata-mata dan tidak mempunyai kuasa-kuasa undangundang untuk mengikat pihak-pihak dalam tuntutan ini.

[73] Dalam kes ini Mahkamah berpendapat adalah sewajarnya jumlah penyelesaian RM200,000.00 tersebut dibayar oleh syarikat insurans kepada Defendan Pertama melalui akaun peguamcara dan klien Tetuan P.S. Ranjan & Co.

What are the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines?

[77] The BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines were issued by BNM on 5 October 2006 pursuant to s 201 of the IA 1996. Section 201 states:

"The Bank may issue guidelines, circulars, or notices in respect of this Act relating to the conduct of the business and affairs of a licensee".

[78] The IA 1996, together with the Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989 ("BAFIA"), the Exchange Control Act 1953 and the Payment Systems Act 2003 ("collectively referred to as "the repealed Acts"), were repealed by the Financial Services Act 2013 (Act 758) ("FSA"). The FSA came into force on 30 June 2013.

[79] Section 273 of the FSA is the savings provision in respect of licences granted under the repealed Acts. Subsection 273(1)(a) of the FSA expressly states that (i) licences granted under s 6(4) of BAFIA for banking business or merchant banking business, and (ii) licences granted under s 16 of the IA 1996 to carry on insurance business under that Act, are deemed granted under s 10 of the FSA authorising such licensed persons to carry on banking business, merchant banking business or insurance business, as the case may be. Subsections 273(1)(a) and (2) of the FSA reads:

273. Savings in respect of licenses granted under repealed Acts

(1) Subject to the provisions of subsection (2)-

(a) a licence granted to a person by the Minister-

(i) under subsection 6(4) of the repealed Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989 to carry on banking business or merchant banking business, as the case may be, under that Act; and

(ii) under s 16 of the repealed Insurance Act 1996 to carry on insurance business under that Act,

shall be deemed to be a licence granted under s 10 authorizing such person to carry on banking business, investment banking business or insurance business, as the case may be;

............

(2) The persons referred to in subsection (1) shall continue to be subject to the conditions applicable to it before the appointed date as if such conditions were imposed under this Act.

[Emphasis added]

[80] Dr Wahab's insurer, P&O Insurance, is a company that was licensed under s 16 of the IA 1996 to carry on insurance business under the IA 1996, and following the repeal of the IA 1996, is licensed to carry on insurance business under s 10 of the FSA. Accordingly, by virtue of s 273(1) of FSA, P&O Insurance and other insurance companies previously licensed under the IA 1996, are deemed licensed under s 10 of FSA to carry on insurance business.

[81] The insurance business is one of the "licensed business" and an "authorised business" under s 2 of the FSA. "Licensed business" is defined as "a banking business, insurance business or investment banking business", and an "authorised business" is defined as "a licensed business or an approved business".

[82] As a person licensed to carry out authorised business, P&O Insurance is an "authorised person" under the FSA, and is accordingly, subject to the terms and conditions of the license issued by the Minister under s 10 of the FSA and to the provisions of the FSA.

Who Is BNM? What Are Its Powers And Functions?

[83] BNM is the Central Bank of Malaysia. It was established under the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 1958 (Act 519). The Act was repealed by Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009 (Act 701) ("BNM Act 2009").

[84] Pursuant s 3 of BNM Act 2009, BNM continues to exist under the BNM Act 2009 and is subject to the provisions of the said Act. Section 3 of the BNM Act 2009 reads:

3. The Bank established under Central Bank of Malaysia Act 1958

(1) Notwithstanding the repeal of the Central Bank Act of Malaysia 1958 by s 99, the body corporate established under the repealed Act under the name "Bank Negara Malaysia" or, in English "Central Bank of Malaysia" shall continue to be in existence under and subject to the provisions of this Act.

[85] BNM's principal object stipulated in s 5(1) of the BNM Act 2009 is "to promote monetary stability and financial stability conducive to the sustainable growth of the Malaysian economy". Its primary functions, stipulated in s 5(2), include regulating and supervising financial institutions that are subject to the laws enforced by BNM.

[86] BNM derives its powers and functions under two statutes: ie the BNM Act 2009 and the FSA. Section 7(2) of the FSA expressly states that the BNM's powers and function under the FSA are in addition to and not in derogation of its powers and functions under the BNM Act 2009.

[87] Section 5(3) of the BNM Act 2009 expressly provides BNM with "all the powers necessary, incidental or necessary to give effect to its objects and carry out its functions". And s 7(1) of the FSA empowers BNM to "exercise the powers and perform the functions under this Act in a way which it considers most appropriate for the purpose of meeting the regulatory objectives of this Act and the Governor shall exercise such powers and perform such functions of the Bank on its behalf."

[88] BNM's powers to issue guidelines, by-laws, circulars, standards or notices are derived from s 95 of the BNM Act 2009. Section 95 of the BNM Act 2009 states:

95. Power to issue guidelines, etc.

The Bank may, for-

(a) giving effect to its objects and carrying out its functions or conducting its business or affairs;

(b) giving full effect to any provision of this Act; or

(c) the further, better or more convenient implementation of the provisions of this Act,

generally in respect of this Act, or in respect of any particular provision of this Act, or generally in respect of the conduct of the Bank, issue such guidelines, by-laws, circulars, standards or notices as the Bank may consider necessary or expedient.

[Emphasis added]

[89] Section 272 of the FSA is the savings and transitional provision of the FSA. Pursuant to subsection 272(b) of the FSA, every guideline, direction, circular or notice issued under the repealed Acts issued before 30 June 2013 are deemed to be "standards" that have been lawfully specified under the FSA and shall remain in full force and effect in relation to the person to whom it applied until amended or revoked. Additionally, under the catch-all provision in subsection 272(m), BNM's actions under the repealed Acts, are deemed to have been done under the FSA and continues to be valid and lawful under the FSA. Subsections 272(b) and (m) of the FSA reads:

272. Savings and transitional Notwithstanding s 271-

(b) every guideline, direction, circular or notice under the repealed Acts in relation to any matter which corresponds with any provision of this Act, issued before the appointed date and in force immediately before the appointed date, shall be deemed to be standards which have been lawfully specified under such provisions of this Act and shall remain in full force and effect in relation to the person to whom it applied until amended or revoked;

...............

(m) all other acts or things done under the repealed Acts shall be deemed to have been done under this Act and accordingly, shall continue to be valid and lawful under this Act.

[Emphasis added]

[90] Therefore, pursuant to subsection 272(b) of the FSA, the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are deemed to be standards and shall remain in full force and effect until it is amended or revoked.

[91] And pursuant to subsection 272(m) of the FSA, all BNM's actions and things done under the IA 1996 is deemed to be done under the FSA and continues to be valid and lawful under the FSA.

[92] What are "standards"? "Standards" as defined in s 2 of the FSA includes any obligation or requirement as specified by BNM under the Act. Section 2 of the FSA reads:

"standards" includes any obligation or requirement as specified by the Bank under this Act and such standards may contain any interpretative, incidental, supplemental, consequential and transitional provisions as the Bank considers appropriate".

[93] "Standards" is defined in the FSA "to include" the matters stated therein: it is not defined "to mean" what is stated therein. This Court in Tenaga Nasional Bhd v. Tekali Prospecting Sdn Bhd [2002] 1 MLRA 351 and in Yii Ming Tung v. Public Prosecutor [2015] 2 MLRA 227, held that where the expression "includes" is employed to define a word or expression, it signifies that the definition is nonexhaustive; whereas the use of the word "means" indicates that the definition is exhaustive.

[94] Further, the FSA expressly stipulates that non-compliance with any standards is a breach of the FSA. It empowers BNM to act against any person who does not comply with or give effect to any standards under the FSA.

[95] Pursuant to s 234(1) of the FSA, non-compliance with or failure to give any effect to any provision of the FSA; any regulations made under the FSA; any order or direction issued by BNM under the FSA; or any standards, condition, restriction, specification, requirement or code under the FSA, is a breach of the FSA. Section 234(1) reads:

234. Power of Bank to take action

(1) A person has committed a breach under this Act if the person fails to comply with or give effect to-

(a) any provision of this Act;

(b) any regulations made under this Act;

(c) any order made or any direction issued under this Act by the Bank including an order made under s 94 or a direction issued under s 116 or 156, subsection 214(6) or s 216; or

(d) any standards, condition, restriction, specification, requirement or code under this Act.

[Emphasis added]

[96] Therefore, pursuant to s 234(1)(d) of the FSA, failure to comply with or give effect to any standards issued by BNM, is a breach of the FSA. Such standards, by virtue of subsection 272(b) of the FSA, includes the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines that was issued by BNM under the IA 1996. It follows, therefore, that non-compliance with the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines is a breach of the FSA.

[97] BNM is empowered under s 234(3) of the FSA to act against persons who have committed a breach under the Act. The FSA expressly states that BNM — if it is of the opinion that a person had committed a breach — may take any of the actions detailed in subsection 234(3)(a) to (e) of the Act. The actions are:

(a) Make an order in writing requiring the person in breach (i) to comply with or give effect to; or (ii) to do or not to do any act in order to ensure compliance with such standards;

(b) Impose a monetary penalties;

(c) Reprimand in writing the person in breach or require the person in breach to issue a public statement in relation to such breach;

(d) Make an order in writing requiring the person in breach to take such steps as BNM may direct to mitigate the effect of such breach; or

(e) Make an order in writing requiring the person in breach to remedy the breach including making restitution to any other person aggrieved by such breach.

[98] BNM is empowered, under subsections 234(3) and (4)(d) of the FSA, to impose monetary penalties for non-compliance with any standards. Subsection 23(4)(d) of the FSA reads:

4. The Bank may impose a monetary penalty under paragraph (3)(b) only in respect of the following:

(a) breach of any provision set out in Schedule 15;

(b) breach of any requirement under any other provision of this Act where no offence is provided for non-compliance of that requirement;

(c) failure to comply with any requirement imposed under regulations made under this Act where no provision for imposition of penalty is provided for in accordance with para 260(2)(d); or

(d) failure to comply with any standards, code, order, direction, requirement, condition, specification, restriction or otherwise made or imposed pursuant to any provision set out in Schedule 15.

[Emphasis added]

[99] The monetary penalties that BNM can impose under subsection 234(3)(b) are:

(b) subject to subsection (4), impose a monetary penalty-

(i) in accordance with the order published in the Gazette made under s 236 or if no such order has been made, such amount as the Bank considers appropriate, but in any event not exceeding five million ringgit in the case of a breach that is committed by a body corporate or unincorporate or one million ringgit in the case of a breach that is committed by any individual, as the case may be;

(ii) which shall not exceed three times the gross amount of pecuniary gain made or loss avoided by such person as a result of the breach; or

(iii) which shall not exceed three times the amount of money which is the subject matter of the breach,

whichever is greater for each breach or failure to comply;

[100] Additionally, under subsection 234(6) of the FSA, BNM may act against a body corporate or unincorporate, where the breach of the standards, was committed by a person (a) who is a director, controller, officer or partner of the body corporate or unincorporate, or was purporting to act any such capacity; or (b) who is concerned in the management of the affairs of the body corporate or unincorporate.

[101] Moreover, BNM is empowered under subsection 234(9) of the FSA to sue and recover and unpaid monetary penalty as a civil debt to the Government. Additionally, it may pursuant subsection 234(10) of the FSA sue and recover as a civil debt due to the person aggrieved by the breach for failure to comply with any order of restitution made by BNM against a person in breach of the Act. Subsections 234(9) and (10) of the FSA state:

(9) Where a person fails to pay a monetary penalty imposed by the Bank under paragraph (3)(b) within the period specified by the Bank, the penalty imposed by the Bank may be sued for and recovered as a civil debt due to the Government.

(10) Where a person fails to remedy the breach including making restitution to any other person aggrieved by the breach under paragraph (3)(e), notwithstanding any other written law, the Bank may sue for and recover such sum as a civil debt due to the person aggrieved by the breach.

[Emphasis added]

[102] Section 239 of the FSA allows BNM to institute civil proceedings in Court seeking any of the orders detailed in subsection 240(1) of the Act, if it appears to BNM that "there is a reasonable likelihood that any person will contravene or has contravened or will breach or had breached or is likely to fail to comply with or had failed to comply with", among others, standards issued pursuant to any provision of the FSA or any action taken by BNM under subsection 234(3). Section 239 reads:

239. Civil action by Bank

Where it appears to the Bank that there is a reasonable likelihood that any person will contravene or has contravened or will breach or has breached or is likely to fail to comply with or has failed to comply with any-

(a) provisions of this Act;

(b) provisions of any regulations made pursuant to this Act;

(c) order made or direction issued by the Bank under this Act including an order made under s 94 or a direction issued under s 116 or 156, subsection 214(6) or s 216;

(d) standards, condition, restriction, specification, requirement or code made or issued pursuant to any provision of this Act; or

(e) action taken by the Bank under subsection 234(3),

the Bank may institute civil proceedings in the court seeking any order specified under subsection 240(1) against that person whether or not that person has been charged with an offence in respect of the contravention or breach or whether or not a contravention or breach has been proved in a prosecution.

[Emphasis added]

[103] It is clear from the above analysis of the FSA that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are deemed to be standards under the FSA, the noncompliance of which is breach of the FSA. If the licensed insurance companies fail to comply with or give effect to BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines, BNM may take any of the actions stipulated in the FSA against the non-compliant insurance companies, including to impose a monetary penalty against the said insurance company, and/or make an order of restitution. And if the noncompliant insurance company fails to pay the monetary penalty or the order of restitution imposed on it, BNM may sue for and recover the unpaid penalty or sum ordered as restitution as a civil debt under subsections 234(9) and (10) of the FSA.

[104] Hence, P&O Insurance, and other insurance companies licensed under the FSA, are compelled to comply with and give effect to the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines. They would be in breach of the FSA if they fail to comply with or give effect to the said Guidelines.

[105] The issue of whether guidelines issued by BNM have the force of law have been considered by the High Court several times. In Affin Bank Bhd v. Datuk Ahmad Zahid Hamidi [2005] 1 MLRH 64, the High Court held that guidelines issued by BNM under BAFIA have the force of law.

[106] The High Court in Diana Chee Vun Hsai v. Citibank Bhd [2009] 1 MLRH 881, held that the credit card guidelines issued by BNM under the Payment Systems Act 2003 are "other instrument made under any Act' and are therefore subsidiary legislation.

[107] Similarly, the High Court in Development & Commercial Bank Bhd v. Cheah Theam Swee [1989] 1 MLRH 332 held that the ECM notices issued under the Exchange Control Act 1953 are subsidiary legislation. Zakaria Yatim J (as he then was) said:

"It is clear that under the Exchange Control Act, the Controller is given the power to give directions. The manner in which the directions are to be given is provided in s 39(2) of the Act. All the ECM notices exhibited to the affidavits filed by the plaintiffs and the defendant are directions made in accordance with s 39(2). I agree with Mr C Das that these ECM notices are subsidiary legislation as defined in s 2 [sic] of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967. Under the Interpretation Act it is not mandatory that these ECM notices be published in the Gazette before they come into force. There is no provision in the Exchange Control Act to say that the notices shall be made through publication in the Gazette.

[108] In Nabors Drilling (Labuan) Corporation v. Lembaga Perkhidmatan Kewangan Labuan [2018] 2 SSLR 201, (citing with approval the cases of Affin Bank Bhd v. Datuk Ahmad Zahid Hamidi [2005] 1 MLRH 64 and Diana Chee Hsui v. Citibank Bhd [2009] 1 MLRH 881) Ravinthran Paramaguru J (as he then was) held that guidelines issued by the Labuan Offshore Financial Services Authority ("LOFSA") pursuant to s 4A of the Labuan Financial Services Authority Act 1996 have the force of law.

[109] As discussed in para [78] above, BAFIA, the Payment Systems Act 2003, the Exchange Control Act 1953, as with the IA 1996, are statutes that were repealed by the FSA in 2013. Accordingly, under s 272 of the FSA, the guidelines issued by BNM under these repealed Acts are deemed to be standards to have been lawfully specified under the FSA and shall have full force and effect until amended or revoked.

[110] "Subsidiary legislation" is defined in s 3 of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967 (Act 388) ("the Interpretation Acts") as:

"subsidiary legislation" means any proclamation, rule, regulation, order, notification, by-law or other instrument made under any Act, Enactment, Ordinance or other lawful authority and having legislative effect;

[111] Accordingly, based on the FSA, the Interpretation Acts, and the case law set out above, we find that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines is piece of the subsidiary legislation, which has the force of law until amended or revoked. The BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines were neither amended nor revoked at the time the Settlement Agreement was entered between the plaintiff and the defendants in Suit 75.

[112] Given the circumstances, we find that the argument advanced by Rashid's counsel regarding the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines — namely, that they are no longer good reference due to their issuance under the now-repealed IA 1996, and that they are merely guidelines, without the force of law — is untenable.

Findings on Issue (II)

[113] For the above reasons, we conclude that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines constitute a piece of subsidiary legislation with the force of law.

[114] Consequently, we find that the learned High Court Judge erred when she found that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines were mere guidelines lacking the force of law.

Issue (III) By Making The Payment Cheque For The Settlement Sum In Favour Of The Plaintiff Did Dr Wahab And/Or His Insurer (A) Refuse To Recognise The Authority Given By Law For A Solicitor To Receive Payment On Behalf Of Their Client, Or (B) Ignore A Solicitor's Lien On Costs Owed By Their Client?

[115] Rashid's case in both these Appeals is that Dr Wahab's and/or his insurer's action, in making the payment of the RM145,000.00 in favour of Rashid, had undermined Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co's solicitor's lien over costs and/or fees owed by Rashid to the firm.

[116] What is a solicitor's lien? It is a legal right recognised under common law, allowing a solicitor to retain a client's document or property in its possession until the client settles sums due and payable to the solicitor, under a bill of costs or an order to tax the costs.

[117] The Federal Court in V Manuel v. Omar Bin Haji Ahmad & Ors [1974] 1 MLRA 192 held:

The appellant's contention for his costs appeared to be founded on a prior right by way of lien.

.............

Further, if he had a claim for solicitor's costs, the claim was at best indeterminate until he had presented a proper bill for his costs which was accepted by his client or obtained an order to tax his costs. The stark fact was that he had at no time presented any bill, nor had he obtained an order to tax, which he must do if his client refused to accept his bill. The result was that the amount of costs, if any, due to him had still to be determined.

[Emphasis added]

[118] This common right is codified in r 9.02 of the Rules and Ruling of the Bar Council Malaysia which states:

9.02 Solicitor's lien and right of set-off

(1) A law firm may, after a bill of costs had been rendered, set-off or deduct from monies payable to a client, such sum as may be due and payable by the client to the firm under the bill.

[119] Rule 7(a)(v) of the Solicitors' Account Rules 1990, made by the Bar Council pursuant to s 78(1) and (2) of the Legal Profession Act 1976 (Act 166), allows a solicitor to draw money from a client's account to pay the solicitor's costs under a bill of costs. Rule 7(a)(v) of the Solicitors' Account Rules 1990 states:

There may be drawn from client account

(a) in the case of client's money-

...............

(v) money properly required for or towards payment of the solicitor's costs where a bill of costs or other written intimation of the amount of the costs incurred has been delivered to the client and the client has been notified that money held for him will be applied towards or in satisfaction of such costs.

[Emphasis added]

[120] This Court in Zulpadli & Edham v. Inai Offshore & Marine Engineering Sdn Bhd [2011] 2 MLRA 101 recognised a solicitor's lien as a right to retain a client's document and property pending payment of the solicitor's bill. However, a solicitor's lien is a mere passive and possessory right: it does not give the solicitor any right of enforcement.

[121] In Messrs Roland Cheng & Co v. Konkamaju Sdn Bhd [2013] 7 MLRA 101, citing our earlier decision in Zulpadli & Edham v. Inai Offshore & Marine Engineering Sdn Bhd [2011] 2 MLRA 101, we held that at common law, a solicitor has a right or lien to retain a client's property in his possession until he is paid costs due to him in his professional capacity.

[122] In M Wealth Corridor Sdn Bhd v. Chan Tse Yuen & Co [2018] 4 MLRH 256, one of the issues before the High Court was whether the defendant solicitor in that case possessed a lien over stamp duty documents and the stamp duty sum in order to protect its legal fees and disbursements. In considering the issue, Nantha Balan J (as he then was) having thoroughly analysed English and Malaysian case law relating to solicitor's lien held:

[148] Thus, the principle that may be culled from the abovementioned cases is that the lien exists over what the solicitor has in his possession and not over what he did not have. The next important principle is that the lien is a passive and possessory right. It is not an active and enforceable right. What this means is that the solicitor is entitled to lawfully hold on to whatever documents belonging to the client until the solicitor's fees and disbursements are paid or until the taxed fees and disbursements are paid.

[Emphasis added]

[123] The legal principle governing a solicitor's lien, as derived from the aforementioned cases, is that a solicitor holds a lien over the documents or property of its client that are in the solicitor's possession. This lien ensures payment of monies due to the solicitor, either pursuant to a bill of costs or an order to tax the costs for work performed.

[124] However, in this case, at the time Dr Wahab's solicitors delivered the P&O Cheque to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, the said firm had not issued a bill of costs of its fees and disbursement for representing Rashid in Suit 75. Mr Siththaranjan Paramalingam (a.k.a. P.S. Ranjan) (DW1) testified during the trial in Suit 281 that the firm has yet to deliver the bill of costs to Rashid. His testimony (at Enc. 4 Rekod Rayuan Jilid 2A Bhgn. B at pdf. 134-135) is reproduced below:

[125] Mr P.S. Ranjan clarified during re-examination by Rashid's counsel that that Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co will only issue a bill of costs to its client, if it wants to deduct money from the firm's client account. His testimony (at Enc. 4 Rekod Rayuan Jilid 2A Bhgn. B pdf. 176) is reproduced below:

[126] We note that the High Court did not address the existence of a solicitor's lien. Instead, without considering P.S. Ranjan's testimony that his firm had not issued any bill of costs to Rashid and would only do so if intending to withdraw funds from the firm's client account, the learned Judge, in para [60] of the GOJ, expressed her view that the words "to the Plaintiff should also refer to "Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co" She further stated that the Settlement Sum should be paid to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, in light of the costs owed by Rashid to the firm.

Findings On Issue (III)(a) and (b)

[127] As we have found in Issues (I) and (II) above, pursuant to the Settlement Agreement and the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines, Dr Wahab's solicitors are obliged to make the payment of the Settlement Sum to Rashid.

[128] In answer to Issue (III)(a), we find that by their conduct, Dr Wahab's solicitors and his insurer did recognise a solicitor's right to receive payment on behalf of its clients. Dr Wahab's solicitors, Messrs Low Aljafri, had delivered the P&O Cheque for Dr Wahab's portion of the Settlement Sum to Rashid's solicitors, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co.

[129] The facts show that Messrs Low Aljafri did not on any occasion deliver the P&O Cheque to Rashid directly. Even after the cheque was rejected and returned by Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, Messrs Low Aljafri resent the cheque to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, which was rejected and returned again by the latter.

[130] In answer to Issue (III)(b), we find that Rashid failed to prove his allegation that Dr Wahab and/or his insurer in making the P&O Cheque in Rashid's favour and delivering the said cheque to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, had ignored a solicitor's lien on costs owed by its client. P.S. Ranjan himself testified during the trial, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co had not issued a bill of costs to Rashid at the time the payment cheques for the Settlement Sum were delivered to the firm by Dr Wahab, Dr Arul and the Hospital's solicitors.

[131] As no bill of costs had been issued to Rashid at the time the P&O Cheque was delivered to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co, there were no determined costs due or payable by Rashid to the firm. It is a well- established principle that a solicitor's lien cannot attach to indeterminate costs: see the Federal Court's decision in V Manuel v. Omar Bin Haji Ahmad & Ors.

[132] Furthermore, a solicitor's lien is a passive and possessory right, limited to the retention of a client's documents or property in the solicitor's possession: see Zulpadli & Edham v. Inai Offshore & Marine Engineering Sdn Bhd [2011] 2 MLRA 101; Messrs Roland Cheng & Co v. Konkamaju Sdn Bhd [2013] 7 MLRA 101. As held by the English Court of Appeal case of Barrat v. Gough Thomas [1950] 2 All ER 1048 (cited with approval by this Court in Zulpadli & Edham v. Inai Offshore & Marine Engineering Sdn Bhd [2011] 2 MLRA 101):

The nature of a solicitor's general retaining lien has more than once been authoritatively stated. It is a right at common law depending, it has been said, on implied agreement. It has not the character of an incumbrance or equitable charge. It is merely passive and possessory, that is to say, the solicitor has no right of actively enforcing his demand. It confers on him merely the right to withhold possession of the documents or other personal property of his client or former client - in the words of Sir E Sugden in Blunden v. Desart (2 Dr & War 418):

"...to lock them up in his box, and to put the key into his pocket, until his client satisfies the amount of the demand."

[Emphasis added]

[133] By rejecting and returning the P&O Cheque, along with the other two cheques delivered by Dr Arul's and the Hospital's insurers, Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co no longer retained possession of the cheques representing the Settlement Sum.

[134] Consequently, even if Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co had issued a bill of costs to Rashid at the time the P&O Cheque was delivered to the firm, the rejection and return of the cheque to Messrs Low Aljafri meant that the firm no longer had a possessory right over it. It is trite that, without possession, no possessory rights exist.

Conclusion

[135] Based on the foregoing analysis and reasoning, we find that, pursuant to the Settlement Agreement, the defendants in Suit 75 agreed to pay the Settlement Sum to Rashid, the plaintiff in Suit 75. Additionally, we conclude that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines constitute subsidiary legislation under the FSA.

[136] Furthermore, we determine that Dr Wahab's insurer issued the payment cheque for Dr Wahab's portion of the Settlement Sum in Rashid's favour, in compliance with the terms of the Settlement Agreement and the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines.

[137] Regarding the issues raised by Rashid, we find that he had failed to prove his claim that Dr Wahab and/or his insurer issued the payment cheque in Rashid's favour either due to a refusal to recognise a solicitor's authority to receive payment on behalf of its client or because they ignored a solicitor's lien on costs owed by its client.

[138] Consequently, we find that the High Court was plainly wrong in interpreting the words "to the Plaintiff' in the Settlement Agreement to include "to Messrs P.S. Ranjan & Co"; and in determining that the BNM Claims Settlement Guidelines are merely guidelines without any force of law.

[139] We find that these errors justify us overturning the decision of the High Court in Suit 218.

Decision

[140] Therefore, we unanimously allow Appeal 314 and dismiss Appeal 1164.

[141] Costs to Dr Wahab in the sum of RM50,000.00 here and below subject to the allocatur fee.