Federal Court, Putrajaya

Hasnah Mohammed Hashim CJM, Rhodzariah Bujang, Nordin Hassan FCJJ

[Civil Appeal No: 01(f)-3-02-2024(B)]

12 March 2025

Land Law: Acquisition of land — Compensation — Compensation awarded by Land Administrator for alleged surrendered land by 1st respondent in nominal sum of RM10.00 — Application of proviso to s 49(1) Land Acquisition Act 1960 — Question of law — Whether there was valid surrender of impugned land by 1st respondent to State Authority

This was an appeal by the appellant, Sistem Lingkaran Lebuhraya Kajang Sdn Bhd ('SILK'), against the Court of Appeal's decision setting aside the High Court's ruling which, among others, upheld the compensation awarded by the Land Administrator for the alleged surrendered land ('impugned land') by the 1st respondent, Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd ('Orchard Circle'), in the nominal sum of RM10.00. The Court of Appeal further ordered that the case be remitted to the High Court before the same judge for a hearing on the assessment of the impugned land. The main issues in the present appeal were: (i) the application of the proviso to s 49(1) of the Land Acquisition Act 1960 ('LAA 1960'); (ii) what amounted to a question of law?; (iii) whether there was a question of law in the present case; and (iv) whether there was a valid surrender of the impugned land by Orchard Circle to the State Authority.

Held (dismissing the appeal with costs by way of majority decision)

Per Nordin Hassan FCJ delivering the majority judgment of the court:

(1) The proviso to s 49(1) of the LAA 1960 was clear that there ought to be no appeal on a decision that comprised the award of compensation. However, if a question of law concerning compensation arose, the door was still open for further appeal to the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court. The interpretation of the proviso had been made by the Federal Court in Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat & Another Case ('Semenyih Jaya '). On the interpretation of the proviso to s 49(1), in another case of Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Johor v. Nusantara Daya Sdn Bhd ('Nusantara Daya'), the Federal Court acknowledged the proposition of law in Semenyih Jaya but emphasised that the question of law must be given a narrow interpretation. (paras 4-6)

(2) A question of law essentially involved the interpretation of the law and the application of legal principles to the facts of a case. There was a plethora of cases that discussed the meaning of the question of law, inter alia, the Federal Court case of Amitabha Guha & Anor v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat ('Amitabha Guha'). The Federal Court in Nusantara Daya had accepted the proposition set out in Amitabha Guha with a rider that it should not be given a liberal interpretation that negated the clear intent of s 49(1) of the LAA 1960 and amounted to an appeal on compensation. (paras 7-8)

(3) Having considered the material facts in this case, it was clear that the issue of the surrender of the land needed to be determined by the Court and it was a question of law as the validity of the surrender of land was governed by the National Land Code ('NLC'), particularly ss 196 to 201. In this instance, it involved the interpretation and the application of the said provisions to the facts of this case as was done by the Land Administrator, the High Court, and the Court of Appeal in arriving at their respective decisions. The guidelines to determine the question of law in Amitabha Guha had been satisfied in the present case and even the narrow interpretation of the question of law in Nusantara Daya had been complied with. The appeal in this case, in pith and substance, was not an appeal against the inadequacy of compensation. Furthermore, the question posed in this case had some similarities with the 2nd question of law posed and answered by the Federal Court in Bayangan Sepadu Sdn Bhd v. Jabatan Pengairan Dan Saliran Negeri Selangor & Ors. As a result, there was a question of law in the present case and thus, the appeal of Orchard Circle to the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court was not barred by the proviso to s 49(1) of the LAA 1960. (paras 24-26)

(4) Orchard Circle was the registered proprietor of the impugned land, while Arab Malaysian Merchant Bank was the chargee since 4 November 1997. Both entities had legal interest in the impugned land and thus, under s 196(1)(a) read with s 196(2)(a) of the NLC, their written consent was required before the State Director could approve the surrender of the impunged land. Unfortunately, no such consent was obtained in this case. Hence, the provision of s 196(1) of the NLC had not been complied with. In this regard, SILK's counsel submitted that the filing of Form 12B under s 200 of the NLC showed that Orchard Circle had consented to the surrender of the impugned land, but this contention was flawed for the following reasons. Firstly, Form 12B filed by Orchard Circle was not a written consent as envisaged under s 196(1)(c) of the NLC, which stated that a written consent must be given before an application could be made. Therefore, a separate written consent should have been provided beforehand for the application to surrender the land through Form 12B. Secondly, s 200(1) of the NLC mandated that the application be accompanied, among others, by written consent, which was lacking in this case. In the circumstances, the contention that Form 12B was the written consent by Orchard Circle under s 196(1)(c) was untenable. Besides, it was an undisputed fact that the chargee, Arab Malaysian Merchant Bank, had also not provided any written consent for the surrender of the land. (paras 32-37)

(5) The High Court, in coming to its decision that there was an effective surrender of the impugned land, had failed to address the pertinent issue of the absence of written consent from both Orchard Circle and Arab Malaysian Merchant Bank, as required under s 196(1) of the NLC. Additionally, the Land Administrator also failed to comply with the procedure of s 201(4) of the NLC upon approval of the surrender of the impugned land. Specifically, the Land Administrator was required to revise the rent payable by the proprietor, notify the proprietor of the approval and make a memorial of the surrender on the register and the documents of title; none of which had been completed. The provisions of the NLC on the conditions of a valid surrender of land were unambiguous, of general application and without any exception. Since there was no valid surrender of the impugned land to the State Authority, the compensation for the impugned land needed to be assessed and, as such, the Court of Appeal's order remitting the case to the High Court for the assessment of the impugned land was most appropriate. (paras 38-42)

Per Hasnah Mohammed Hashim CJM (dissenting):

(6) Orchard Circle's appeal to the Court of Appeal was centred on compensation on the basis that there was no valid surrender of the impugned land. In light of the provisions under the LAA 1960 and, in particular, ss 37(2), 40D and 49(1) thereof and s 68(1)(d) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964, and applying the principles in Semenyih Jaya and Nusantara Daya, Orchard Circle had no right of appeal as the central issue was the amount of compensation. The complaints by Orchard Circle concerned issues of fact, along with the application of valuation principles and the computation of compensation; therefore, such issues could not be regarded as questions of law. On the facts, the issue of the Land Administrator's failure to endorse the memorial, which resulted in no effective surrender due to non-endorsement on the title, was only raised when Orchard Circle was informed of the acquisition of the SILK Highway. By that time, Orchard Circle had already agreed to surrender the impugned land when it applied for the surrender which was subsequently approved in January 1999. Therefore, no market value could be ascribed to the impugned land. Furthermore, the non-endorsement of the surrender on the title had no relevance to the determination of the land's market value, as Orchard Circle had already agreed to surrender the impugned land. (paras 130-131)

(7) There was a serious misdirection by the Court of Appeal remitting the matter to the High Court for an assessment of the impugned land's value on the basis that it had not been properly surrendered. At all material times before the High Court, Orchard Circle was not denied the right to present its case on the basis that the impugned land had yet to be surrendered. To permit a party, in this case, Orchard Circle, to appeal a claim on compensation on the basis of non-endorsement on the title due to the delay by Orchard Circle itself to surrender the title to the Land Office, would have far-reaching consequences. It would open the floodgates which would ultimately result in a dramatic increase of appeals on compensation, thereby contravening and circumventing the provisions of the LAA 1960 as well as the principles enunciated by the Federal Court in Semenyih Jaya and Nusantara Daya. (paras 132-133)

(8) Based on the aforementioned reasons and in light of the settled principles, there was merit in the issues raised by the appellant. (para 134)

Case(s) referred to:

Amitabha Guha & Anor v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat [2021] 2 MLRA 19 (folld)

Bayangan Sepadu Sdn Bhd v. Jabatan Pengairan Dan Saliran Negeri Selangor & Ors [2022] 2 MLRA 1 (folld)

Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat & Ors [2021] 1 MLRA 54 (distd)

Pengarah Tanah Dan Galian Wilayah Persekutuan v. Sri Lempah Enterprise Sdn Bhd [1978] 1 MLRA 132 (refd)

Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Gombak lwn. Huat Heng (Lim Low & Sons) Sdn Bhd [1990] 2 MLRA 56 (refd)

Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Johor v. Nusantara Daya Sdn Bhd [2021] 4 MLRA 466 (folld)

Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat And Another Case [2017] 4 MLRA 554 (folld)

Sistem Lingkaran Lebuhraya Kajang Sdn Bhd v. Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 6 MLRA 597 (refd)

Tan Yen Foon v. Pentadbir Tanah Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur [2007] 3 MLRH 705 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, s 68(1)(d)

Land Acquisition Act 1960, ss 3, 7, 8(4), 9, 12, 14(1), 22,36, 37(2), 38(1), 40D, 49(1),First Schedule, s 1

National Land Code, ss 131, 196(1)(a), (c), (2)(a), 197, 198, 199, 200(1)(c), 201(2), (4)(a),( b), (c), 204, 244(2), 281(4)

Counsel:

For the appellant: Thangaraj Balasundram (Karen Lee Foong Voon, Cheah Kha Mun & Ho Zhi Yee with him); M/s Wong Kian Kheong

For the 1st respondent: Sri Dev Nair (Mohd Hafiz Mahmund & Ashok Kumar Puri with him); M/s Sri Dev And Naila

For the 2nd respondent: Etty Eliany Tesno (Nor Fariza Ridzuan with her); Selangor Legal Advisor's Office

[For the Court of Appeal judgment, please refer to Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat & Anor [2024] 3 MLRA 881]

JUDGMENT

Nordin Hassan FCJ (Majority):

[1] This is an appeal by SILK against the decision of the Court of Appeal on 25 August 2023 that set aside the decision of the High Court which among others, maintained the compensation awarded by the Land Administrator for the alleged surrendered land (impugned land) in the nominal sum of RM10.00. The Court of Appeal further ordered that the case be remitted to the Shah Alam High Court before the same judge for a hearing of the assessment of the impugned land.

The Main Issues

[2] The main issues in the present appeal are as follows:

(i) the application of the proviso of s 49(1) of the Land Acquisition Act 1960 (LAA 1960).

(ii) what amounts to a question of law?

(iii) was there a question of law in the present case?

(iv) whether there was a valid surrender of the impugned land by Orchard Circle to the State Authority.

The Application Of The Proviso Of Section 49(1) Of The LAA 1960.

[3] Section 49(1) of the LAA 1960 provides:

"49. (1) Any person interested, including the Land Administrator and any person or corporation on whose behalf the proceedings were instituted pursuant to s 3 may appeal from a decision of the Court to the Court of Appeal and to the Federal Court:

Provided that where the decision comprises an award of compensation there shall be no appeal therefrom"

[4] The reading of the above proviso is clear that there shall be no appeal on a decision that comprises the award of compensation. However, if there is a question of law concerning compensation, the door is still open for further appeal to the Court of Appeal and the Federal Court.

[5] The interpretation of the proviso has been made by this Court in Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat & Another Case [2017] 4 MLRA 554 where this was said:

"[155] To sum up, the proviso to sub-section 49(1) of the Act does not represent a complete bar on all appeals to the Court of Appeal from the High Court on all questions of compensation. Instead, the bar to appeal in sub-section 49(1) of the Act is limited to issues of fact on ground of quantum of compensation. Therefore, an aggrieved party has the right to appeal against the decision of the High Court on questions of law."

[6] On this interpretation of the proviso to s 49(1), in another case of Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Johor v. Nusantara Daya Sdn Bhd [2021] 4 MLRA 466, this Court acknowledged the proposition of law in Semenyih Jaya but added that the question of law must be given a narrow interpretation. The Court explained:

"[37] Although the Federal Court in Semenyih Jaya decided that there was still a right of appeal from a decision of the High Court on compensation if the appeal was on questions of law, that the bar was 'limited to issues of fact on ground of quantum of compensation', there was, however, no definition or indication as to what may amount to a question of law within the context and purpose of s 49(1), especially its proviso. Certainly, at no time did the Federal Court in Semenyih Jaya define or even attempt to define in any manner whatsoever, the meaning to be ascribed to the phrase 'question of law'. And, we must immediately dispel any thoughts harboured to the effect that the six questions of law or even the two constitutional questions posed in Semenyih Jaya necessarily fall within the ambit and meaning of question of law as envisaged in para [155] of its decision."

.....

[61] Yet another reason why a narrow construction must be given to the phrase 'question of law' is that in Semenyih Jaya, the specific question of law posed in respect of s 49(1) itself was directed at whether there could nevertheless be an appeal on compensation where it involves a question of law. To this, the Federal Court answered in the affirmative.

[81] The allegations of acting without evidence or acting against the evidence of a particular witness or report; or how a particular piece of evidence is to be treated, as raised in the questions posed, are actually complaints generally made in order to meet the general principles for appellate intervention. The views expressed by Michael Barnes in The Law of Compulsory Purchase and Compensation and by Lord Denning MR in Ashbridge Investments Ltd v. Minister of Housing A nd Local Government [1965] 1 WLR 1320, that such complaints are points of law which may be raised on appeal and for which reasons the appellate court may interfere in the trial court's findings, is generally correct in the context and in relation to appeals sans the proviso to s 49(1). But for the clear terms of the proviso, such appeals on points of law may be entertained even if the appeal is on compensation or the amount of compensation. However, in the presence of the plain terms of the proviso, and the restrictive reading which we must give to the meaning of question of law as allowed in Semenyih Jaya, such complaints or grounds do not render or make the questions posed, questions of law."

What Amounts To A Question Of Law?

[7] A question of law essentially involves the interpretation of the law and the application of the law to the facts of the case. There is a plethora of cases that discussed the meaning of the question of law and among others the Federal Court case of Amitabha Guha & Anor v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat [2021] 2 MLRA 19 which discussed the issue as follows:

"What Is A Question of Law?

[46] It follows from the preceding paragraph that appeals to the Court of Appeal and to the Federal Court may only be mounted on questions of law. In a general sense, a question of law is an issue involving the interpretation of law (statutes or legal principles) and the application of the law to the facts of each individual case. What is a question of law has also been discussed and formulated in a line of cases:

(i) questions of law are questions about what the correct legal test is. Questions of mixed law and fact are questions about whether the facts satisfy the legal tests: Canada (Director of Investigation And Research v. Southam Inc [1997] 1 SCR 748);

(ii) a question of law is a question concerning the legal effect to be given to a set of undisputed facts. This includes an issue which involves the application or interpretation of a law (Carrier Lumber Ltd v. Joe Martin & Sons Ltd [2003] BCJ No 1602);

(iii) the question of whether a decision-maker has jurisdiction to determine a particular matter is usually considered a question of law reviewable by a court on a standard or correctness (Premium Brands Operating GP Inc v. Turner Distribution Systems Limited [2010] BCJ No 349);

(iv) questions of law involve errors of law committed by a decision-maker. Errors of law includes the application of the wrong law, or a finding of fact in complete absence of any evidence (Southam, supra at [39]; I-Net LINK Inc v. Broadband Communications North Inc [2017] MBQB 146);

(v) questions where there is real doubt as to the law on a particular point (Datuk Syed Kechik Syed Mohamed & Anor v. The Board of Trustees Of The Sabah Foundation & Ors [1998] 2 MLRA 277;

(vi) questions of law include the correctness of (a) pure statements of law (eg, as to correct interpretation of a statutory provision), and (b) the inferring of a conclusion from the primary facts (where the process inference involves assumptions as to the legal effect of consequences of the primary facts) (Director-General Of Inland Revenue v. Rakyat Berjaya Sdn Bhd [1983] 1 MLRA 281)."

[8] This Court in the Nusantara Daya had accepted the proposition set down in the Amitabha Guha with a rider that it should not be given a liberal reading that negates the clear intent of s 49(1) of the LAA 1960 and amounts to an appeal on compensation. At paras [51] and [52] of the case, this was said:

"[51] As a starting point, we would adopt the general proposition as set down in Amitabha Guha, that 'In a general sense, a question of law is an issue involving the interpretation of law (statutes or legal principles) and the application of the law to the facts of each individual case', but with a strong rider and only to that extent. This general proposition must be appreciated, understood, and applied in the context of the proviso to s 49(1), ruled by this court in Semenyih Jaya to be a valid provision of law, that s 49(1) limiting the right of appeal does not violate arts 13 and 121(1B) of the Federal Constitution..

[52] This general proposition also is not to be taken as suggesting, even for the slightest moment, that s 49(1) is to be given a liberal reading so as to render nugatory the clear intent of precluding appeals from decisions of the High Court on compensation. This proposition is not to be read as allowing in any way, what in pith and substance, are appeals on compensation.."

[9] In the Nusantara Daya, it was decided that the questions posed were not questions of law, and the issues raised fell within the parameter of the proviso of s 49(1). The ten questions posed in that case relate to three main points which are:

(i) the issue of making a 10% deduction from the market value.

(ii) the double counting of 5% for location; 10% for access; and yet another 5% for layer when all are three sides of the same pyramid and that separate deductions for similar if not identical characteristics of the scheduled land is a clear instance of double counting.

(iii) finding that the potential development value of the scheduled land had already been factored into the transacted value of Comparable No 1 when that comparable had no development potential.

[10] It was further held in that case that the questions posed were all about the award of compensation and no real questions of law. Paragraphs [79] and [111] of the case state as follows:

"[79] Having examined all the questions posed, whether we take the ten questions as posed or as grouped into the 'three issues', these questions or issues are all about the award of compensation that was made by the High Court, how the final amount was arrived at and how that amount was wrong. At the end of the day, the High Court, assisted by the assessors, made various deductions in order to arrive at the market value. The High Court, as a Land Reference Court was entitled to make those deductions for the reasons stated, as those deductions are very much fact-based decisions, based on evidence adduced, the analysis of such evidence involving the court's appreciation and impression of such evidence when applying principles of valuation to the facts. Room must be given for a divergence of opinion on the evaluation of such evidence; more so when the appeal is statutorily limited."

.....

[111] None of the questions posed by the respondent at the Court of Appeal were real questions of law. We thus unanimously allow the appeal and set aside the decision of the Court of Appeal and restore the decision of the High Court dated 9 August 2018."

Was There Any Question Of Law In The Present Case?

[11] Before answering the above question, it is appropriate to set down the important facts concerning the issue of question of law in the present case.

[12] On 7 June 2011, a second land inquiry was held concerning Orchard Circle's acquired land by the State Authority, the decision of the High Court in a Judicial Review application by Orchard Circle. In this land inquiry, there were two main issues adjudicated by the Land Administrator which were the issues of the surrender of land by Orchard Circle and the issue of compensation. The issue of surrender of the land relates to the Orchard Circle's 17,284.67 sq meters of land which were said to have been surrendered to the State Authority and was awarded nominal compensation of RM10.00 for the surrendered portion. In the land inquiry notes of proceedings dated 7 June 2011, it states:

"LA: Tujuan inkuiri pada pagi ini adalah untuk menentukan sama ada bahagian tanah tersebut telah diserahkan atau pun tidak. Kami akan mendengar keterangan mengenai penyerahan. Siasatan sambungan akan dijalankan bagi menentukan penilaian..."

....

LA: Pada pagi ini, kami akan membuat penentuan mengenai isu penyerahan. Bukan berkenaan penilaian. Boleh kita bersambung dulu mendengar keterangan saksi berkenaan penyerahan."

[13] On 20 April 2012, the Land Administrator decided that there was a surrender of the said land by Orchard Circle to the State Authority which is reflected in his grounds of judgment as follows:

"3.0

Keputusan 3.1 Di dalam pelan pra-perhitungan pecah sempadan (pelan bil. MPKj/PB/ KM/6- 98) yang diluluskan bertarikh 3 September 1998, rezab jalan dan Lorong ditandakan di bawah "kemudahan" bersama-sama dengan Rezab rawatan najis, pencawang Tenaga Nasional Berhad, Simpanan parit, Taman Bandar, Simpanan kolam takungan, Kawasan lapang/hijau dan Tempat letak kereta. Selain daripada itu, buffer zone juga diserahkan melalui Borang 12B (Seksyen 200 KTN 1965, walaupun tidak ditandakan dengan petunjuk). Berdasarkan kepada Borang 12B yang diserah hantar dan diluluskan oleh Pengarah Tanah dan Galian Negeri Selangor pada 11 Januari 1999 maka telah berlaku penyerahan sebahagian daripada tanah bagi lot-lot berkenaan. Maka tanah-tanah tersebut telah menjadi tanah kerajaan (State Land) pada tarikh 11 Januari 1999 dan pihak Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd tidak lagi mempunyai kepentingan ke atas tanah tersebut."

[14] In this regard, the Land Administrator among others, considered s 200 of the National Land Code in coming to his decision that there was a surrender of the impugned land by Orchards Circle to the State Authority.

[15] The matter was later taken up to the Court of Appeal in Sistem Lingkaran Lebuhraya Kajang Sdn Bhd v. Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 6 MLRA 597 which decided among others that the issue of compensation payable and the issue of surrender of the lands be addressed by parties at the land reference proceedings. The order is as follows:

"[37] For reasons stated above, we dismiss Appeal 131 and allow Appeals 114, 121, and 122 and make the following orders:

(a) .....;

(b) .....;

(c) an order that all objections taken in connection with the Land Administrator's findings in the second land inquiry with regard to compensation payable and the issue of surrender of the lands be addressed by the parties at the land reference proceedings

[16] In the land reference proceedings at the High Court, based on the written submission, both parties submitted at length the two issues directed by the Court of Appeal which were the issue of the surrender of the impugned land by Orchard Circle and the issue of compensation. In essence, counsel for Orchard Circle submitted that there was no surrender of the lands under the NLC as the provisions of ss 196(1)(c), 200(1), and 201(4) had not been complied with. Conversely, it was submitted on behalf of SILK that Orchard Circle is estopped from denying that it had agreed to surrender the land based on its conduct in particular, the filing of Form 12B for the surrender which was eventually approved by the Pentadbir Tanah Galian Selangor. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat also took the same position in its submission.

[17] The High Court also considered both issues of the surrender of the lands and compensation separately. As regards the issue of surrender of lands, the High Court was of the view that the provision of s 200 of the NLC had been complied with, and as such the surrender of the lands by Orchard Circle was effective. In the grounds of judgment, this was said:

"[38] In the case before this court, since Form 12B was signed and submitted by OC in compliance with s 200 of the NLC and the Land Office approved the surrender. In the view of this court, even without OC surrendering their original title so in order for endorsement to be made, the surrender is still effective."

[18] Similarly, the High Court had considered s 200 of the NLC and its compliance, in coming to a finding that the surrender of lands by Orchard Circle was effective and maintained the nominal award granted by the Land Administrator for the surrendered land.

[19] At the Court of Appeal, counsel for Orchard Circle among others, raised the same question on the issue of the validity of the surrender of the impugned land. In the Orchard Circle's written submission, the question below was crafted for the determination of the Court:

"QUESTION OF LAW (SURRENDER)

A. WHETHER THE LEARNED JUDGE WAS CORRECT IN UPHOLDING THE LAND ADMINISTRATOR'S FINDING THAT THERE WAS SURRENDER OF 17,284.67 SQUARE METERS OF ORCHARD'S LAND."

[20] It was then submitted, as was raised before the Land Administrator and the High Court, that the provisions of ss 196(1)(c), 200(1), 201(4) of the NLC had not been complied with and as such there was no surrender of the impugned land by Orchard Circle to the State Authority.

[21] Counsel for SILK, on the other hand, among others, submitted that apart from the proviso of s 49(1) of the LAA 1960 is applicable that bars Orchard Circle's appeal, the validity of the surrender of the lands is irrelevant as no value can be ascribed to the land that has been surrendered.

[22] The Court of Appeal as reflected in the grounds of judgment, decided that there were questions of facts and law in the appeal. The issue of whether the procedure for the surrender of land had or had not been complied with is a question of fact and whether the surrender of the impugned land took place is a question of law. At paras [11], [12], and [16] of the grounds of judgment, this was said:

"[11] It is trite that there shall be no appeal against the decision of the High Court when the decision comprises an award of compensation (see s 49(1) of the LAA). In the instant case, the appellant raised a question which is whether the impugned land had or had not been surrendered. This question, in the opinion of this Court, raises a question of fact as well as law.

[12] The finding of whether the procedure for surrender of the impugned land had or had not been complied with is indeed a question of fact. However, the finding of when the surrender of the impugned land took effect is a question of law, in order to determine the latter, it is inevitable that the exercise has to encroach onto the former. Therefore, the question raised by the appellant contains a mixture of both fact and law. The 2nd respondent's counsel's submission that there was no question of law raised before this Court is not entirely correct."

.....

[16] This Court finds it is necessary to examine the provisions of the NLC in Part Twelve — Surrender of Title, particularly from s 196 to s 201 of the NLC, in order to determine when the surrender of the impugned land had been effected under the NLC. The question raised by the appellant is in the form of a question of fact, but in substance is a question of law. Hence, this Court is of the considered view that the appellant's appeal has met the threshold of appealability under s 49(1) of the LAA."

[23] The Court of Appeal also concluded that the issue before the Court is not on the adequacy of the compensation but on whether the value of the impugned land ought to be assessed. This could only be done if the legal issue of the surrender of the impugned land is determined. The Court of Appeal at para [17] explained:

"[17] Flowing from the above, the outcome of the finding of the question of law will definitely have a direct bearing on the award of compensation. However, the issue here in relation to the award of compensation is not about whether the acquisition of the land was adequately compensated or not. The real issue is whether the value of the impugned land ought to be assessed or not. If the law requires the value of the impugned land ought to be assessed or not. If the law requires the value of the impugned land to be assessed, but it was not done, then the issue is not about award of compensation. The material issue is whether the proper adjectival law was administered and accorded to the appellant for the compulsory acquisition of the impugned land. Therefore, in substance, this appeal is not a complaint pertaining to the award of compensation, but pertains to whether the appellant had the right of fair assessment for its impugned land."

[24] Having considered the material facts in the present case and the issue of the surrender of the land by Orchard Circle, it is clear that the issue of the surrender of the land is pertinent to be determined by the court and it is a question of law as the validity of the surrender of land has been laid down in the NLC, particularly from ss 196 to 201. Here, it involves the interpretation and the application of the said provisions to the facts of the present case as were done by the Land Administrator, the High Court, and the Court of Appeal in coming to their decision. The guidelines for determining the question of law in Amitabha Guha have been satisfied in the present case and even the narrow interpretation of the question of law in Nusantara Daya have been complied with. The appeal in the present case, in pith and substance, was not an appeal against the inadequacy of compensation.

[25] Further, the question posed in the present case has some similarities with the 2nd question of law posed and answered by this Court in Bayangan Sepadu Sdn Bhd v. Jabatan Pengairan Dan Saliran Negeri Selangor & Ors [2022] 2 MLRA 1 which was as follows:

"Assuming that Subject Land Lot 18903 was the agreed lot to be surrendered to Majlis Perbandaran Shah Alam (which is denied) whether there was a valid surrender of Subject Land Lot 18903 under s 196(1)(c) read with s 196(2) (a) of the NLC when the consent of the chargee had not been obtained."

[26] As a result, there was a question of law in the present case and as such, the appeal of Orchard Circle to the Court of Appeal and this Court is not barred by the proviso of s 49(1) of the LAA 1960.

Whether There Was A Valid Surrender Of The Impugned Land By Orchard Circle To The State Authority

[27] The National Land Code, in particular ss 196 to 201, has laid down the conditions and requirements for a valid surrender of land. These statutory conditions and requirements must be complied with and adhered to strictly to make the surrender of land legally valid. Parliament enacted the law with the purpose, among others, of protecting the interest of the registered proprietor. The provisions are not meant to be nugatory or otiose. The non-compliance of the statutory requirements would only result in the non-surrendering of the land under the law.

[28] On this issue, the Federal Court in Bayangan Sepadu Sdn Bhd v. Jabatan Pengairan Dan Saliran Negeri Selangor & Ors (supra) succinctly explained in the following words:

[51] It is clear that in order to be a valid surrender, the procedure under s 200 of the NLC must be complied with. With respect, we are of the view that the High Court and the majority in the Court of Appeal erred in law in reaching the decision that there was a valid surrender as the previous owners did not object to the construction of the retention pond and structures on the land. On the factual matrix of the present case, as alluded to earlier in the judgment, there was no evidence to show that any of the procedures in ss 196, 200, and 201 of the NLC had been adhered to. There was no consent in writing from the person or body who has registered interest in the land (CIMB/chargee) as required by s 196(1)(c) read together with s 196(2)(a) of NLC.

[52] We would like to emphasise that the surrender of any private land must be made with the consent of both the registered proprietor and the State Authority and must be strictly complied with the relevant statutory provisions of the NLC. We venture to say that these provisions are made for the purpose of safeguarding the interest of the registered proprietor. Where the procedures as stipulated by the provisions of the NLC are not adhered to, grave doubts are cast on the validity and/or legality of the surrender. In the absence of the consent of CIMB/chargee and by merely relying on the documents and/or letters produced by the respondents as enumerated in para [7] of this judgment, it cannot be assumed that all mandatory requirements under the provisions of the NLC had been adhered to when the State Authority gave its consent for the transfer."

[29] In the Bayangan Sepadu case, this Court held, among others, that as there was no written consent for the surrender of the land from the chargee, CIMB Bank, the provisions of s 196(1)(c) read with s 196(2)(a) has not been complied with, resulting the surrender of land invalid. In that case, there are 2 questions of law posed for the determination of the Federal Court which were:

(i) Assuming that Subject Land Lot 18903 was the agreed lot to be surrendered to Majlis Perbandaran Shah Alam which is denied whether the right of the appellant as the registered owner under ss 89 (conclusiveness of register documents of title) and 340 of the NLC (registration to confer indefeasible title) can be defeated by a promise to surrender the said property made by the Previous Owners; and

(ii) Assuming that Subject Land Lot 18903 was the agreed lot to be surrendered to Majlis Perbandaran Shah Alam (which is denied) whether there was a valid surrender of Subject Land Lot 18903 under s 196(1)(c) read with 196(2)(a) of the NLC when the consent of the chargee had not been obtained.

[30] This Court, in that case, answered both questions in the negative as reflected at para [64] of the judgment as follows:

"[64] For the foregoing reasons, we would answer both the questions of law posed for our determination in the negative..."

[31] Reverting to the present case, it is apt to refer to the relevant provisions of the NLC. Firstly, s 196(1) and (2) states as follows:

"Conditions for approval of surrender

196. (1) No surrender, whether of the whole or a part only of any alienated land, shall be approved by the State Director or, as the case may be, Land Administrator unless the following conditions are satisfied:

(a) that no item of land revenue is outstanding in respect of the land;

(aa) that the land will not create or cause any liabilities to the State Authority;

(b) that the land is not under attachment by any court; and

(c) that every person or body specified in subsection (2) has consented in writing to the making of the application.

(2) The said persons and bodies are—

(a) any person or body who, at the time when the approval was applied for, was entitled to the benefit of any registered interest affecting the land or, as the case may be, the part to be surrendered (including a charge of any lease or sublease);

(b) any person or body having at that time a lien over the said land or part, or over any lease or sublease thereof;

(c) any person or body entitled at that time to the benefit of any tenancy exempt from registration affecting the said land or part, being a tenancy protected by an endorsement on the register document of title; and

(d) any person or body having at that time a claim protected by caveat affecting the said land or part or any interest therein.

(3) No surrender of a part only of any alienated land shall be approved if, in the opinion of the State Director or, as the case may be, Land Administrator, the area of the part is such that a subdivision of the land ought first to be effected."

[32] In the present case, Orchard Circle was the registered proprietor of the impugned land and Arab Malaysian Merchant Bank was the chargee of the land since 4 November 1997. Both entities had legal interest over the impugned land and thus, under s 196(1)(a) read with s 196(2)(a), their consent in writing needs to be obtained before the surrender of the land is approved by the State Director. Unfortunately, there was no such consent in the present case. Hence, the provision of s 196(1) has not been complied with.

[33] In this regard, counsel for SILK submitted that the filing of Form 12B under s 200 of the NLC shows that Orchard Circle had consented to the surrender of the impugned land. This contention is flawed for the following reasons. First, Form 12B filed by Orchard Circle was not a written consent by Orchard Circle envisaged under s 196(1)(c) of the NLC. Section 196(1) (c) states that there must be written consent to the making of the application. Therefore, there must be prior separate written consent to the making of the application for surrender of the land through Form 12B. This is also mentioned in Form 12B itself which states:

"Huraian − Persetujuan dengan bertulis adalah dikehendaki daripada tiaptiap orang-

(i) Yang berhak mendapat faedah daripada apa-apa jua kepentingan berdaftar mengenai bahagian tanah yang hendak diserahkan balik itu (termasuk gadaian apa-apa jua pajakannya)

(ii) .....

(iii) .....

(iv) ....."

[34] Further, s 200(1) of the NLC provides:

"200. (1) Any application for approval by a proprietor wishing to surrender a part only of the land comprised in his title shall be made in writing to the Land Administrator in Form 12B, and shall be accompanied by-

(a) such fee as may be prescribed;

(b) a plan showing the details of the proposal, together with such number of copies thereof as may be prescribed or, in the absence of any such prescription, as the Land Administrator may require;

(c) all such written consents to the making of the application as are required under para 196(1)(c); and

(d) subject to subsection (3), the issue document of title to the land.

(2) Upon receiving any such application, the Land Administrator shall endorse, or cause to be endorsed, a note thereof on the register document of title to the land.

(3) An application under subsection (1) may be submitted without the issue document of title if that document is in the hands of any person as chargee, or has been deposited with any person as security for a loan; but in any such case, the application shall be accompanied instead by a copy of a request by the proprietor, served on that person under subsection 244(2) or, as the case may be, subsection 281(4), for the production of the document at the Land Office within fourteen days of the date thereof.

(4) In a case falling within subsection (3), no action shall be taken on the application until the issue document, or a replacement thereof, is in the hands of the Land Administrator; and accordingly, if the document is not produced pursuant to the request referred to in that subsection, or to any notice served under s 15 on default in compliance with the request, title in continuation (or, where appropriate, a duplicate issue document only) shall be prepared under Chapter 3 of Part Ten as if the circumstances were as specified in para 166(1)(c).

[35] Hence, s 200(1)(c) requires the application for the surrender of land through Form 12B to be accompanied, among others, by written consent as envisaged under s 196(1)(c).

[36] In the circumstances, the contention that Form 12B was the written consent by Orchard Circle under s 196(1)(c) is untenable. Besides, it is an undisputed fact that the chargee of the surrendered land, the Arab Malaysian Merchant Bank also has not given any written consent for the surrender of the land.

[37] The High Court in coming to its decision that there was an effective surrender of the impugned land, had failed to address the pertinent issue of no written consent by Orchard Circle, the proprietor, and the Chargee, Arab Malaysian Merchant Bank, as envisaged in s 196(1) of the NLC.

[38] Be that as it may, the Land Administrator in the present case also failed to comply with the procedure of s 201(4) of the NLC upon approval of the surrender of the impugned land, that is the Land Administrator is required to revise the rent payable by the proprietor, notify the proprietor of the approval and make a memorial of the surrender on the register and the documents of title. These were not done.

Section 201(4) provides:

(4) On approving, or being informed by the State Director that he has approved, the surrender, the Land Administrator shall-

(a) revise (by reference to the estimated area of the part to be retained) the rent payable by the proprietor;

(b) notify the proprietor of the approval and the revised rent; and

(c) make, or cause to be made, a memorial of the surrender on the register and issue documents of title to the land."

[39] In determining the issue at hand in the present case, the Federal Court case of Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat & Ors [2021] 1 MLRA 54 is of no assistance as the issue of surrender of Orchard Circle's impugned land under the NLC was not canvassed in that case.

[40] The provisions of the NLC on the conditions of a valid surrender of land alluded to earlier are unambiguous, of general application and without any exception.

[41] As there was no valid surrender of the impugned land to the State Authority, the compensation for the impugned land needs to be assessed and as such, the order of the Court of Appeal to remit the case to the High Court for the assessment of the impugned land is most appropriate.

Conclusion

[42] Based on the aforesaid reasons, there is no merit in the appellant's appeal for the intervention of this Court. The appeal is dismissed with costs. The decision of the Court of Appeal is affirmed. My learned sister, Justice Rhodzariah has read this broad grounds of judgment in the draft and has agreed to it. My learned sister, Chief Judge of Malaya, Justice Hasnah is dissenting.

Hasnah Mohammed Hashim CJM (Dissenting):

[43] We heard oral submissions by all learned counsels representing the respective parties and at the end of those submissions, we indicated that we needed time to consider the respective submissions. We have now reached our decision. What follows below are my deliberations on the issues raised and my reasons as to why I have so decided.

[44] This appeal emanates from a decision of the High Court in the land reference proceedings where the Learned Judge decided as follows:

(a) that the area of land measuring 17,284.67 square meters has been surrendered (the Surrendered Area) by Orchard Circle Sdn Bhd (OCSB) and that the compensation awarded by the Land Administrator in the nominal sum of RM10.00 for the Surrendered Area is reasonable;

(b) in respect of the area measuring 1,839.10 square meters of the Land (area not surrendered), the learned High Court Judge maintained the Land Administrator's award of RM514,948.00;

(c) late payment charges at the rate of 5% per annum on the sum of RM514,948.00 from the date of issuance of Form "K" on 20 February 2003 until the date of full and final settlement;

(d) costs for the Government assessor in the sum of RM500.00 and costs for the private assessor in the sum of RM500.00 to be borne by OCSB and SILK had been paid; and

(e) the deposit for the Land Reference No 15-99-09/2012 and the Land Reference No 15-100-09/2012 be returned to OCSB and SILK.

[45] The issues in this appeal are as follows:

(a) whether the Surrendered Area has been surrendered is a question of law and if the answer affects an award of compensation, is such a question an issue relating to compensation or a pure question of law?

(b) whether OCSB had a right of appeal against the High Court's decision in light of the provisions under the Land Acquisition Act 1960 (LAA) in particular ss 37(2), 40D and 49(1) of LAA and s 68(1)(d) of Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (CJA);

(c) whether the fact that OCSB had surrendered the Surrendered Area is the correct test to determine 'adequate compensation'?

(d) whether OCSB had effectively surrendered the Surrendered Area in accordance with the provisions of the National Land Code (NLC) is irrelevant consideration in determining 'adequate compensation';

(e) whether the Court of Appeal is correct in its finding that just because the requirements under the NLC for surrender of lands have not been complied with, nominal value could not be ascribed to the said land that have been surrendered especially when the Court agreed that OCSB had intended to surrender the Land for its development?

(f) whether the Court of Appeal is correct in remitting the matter back to the High Court for an assessment of the value of the Surrendered Area on the basis that it has not been surrendered when the learned High Court Judge had considered the issue?

(g) whether the Court of Appeal was correct in its finding that OCSB was not accorded the right to present its case on the basis that the Surrendered Area had yet to be surrendered, when in fact OCSB in its valuation report, had valued the compensation of the entire acquired land, including the Surrendered Area, at market value and claimed for compensation in the sum of RM16,056,000.00.

The Statutory Provisions

[46] It is helpful to refer to the relevant provisions of the National Land Code (NLC) and the Land Acquisition Act 1960 (LAA) before discussing the facts and the proceedings in respect of this appeal.

[47] For ease of reference in respect of the surrender the relevant provisions of the NLC are, ss 196(1)(c), 196(2)(a), 200 and 201 of the NLC are reproduced as follows:

Conditions for approval of surrender

(1) No surrender, whether of the whole or a part only of any alienated land, shall be approved by the State Director or, as the case may be, Land Administrator unless the following conditions are satisfied:

(a) that no item of land revenue is outstanding in respect of the land;

(aa)that the land will not create or cause any liabilities to the State Authority;

(b) that the land is not under attachment by any court; and

(c) that every person or body specified in subsection (2) has consented in writing to the making of the application.

(2) The said persons and bodies are-

(a) any person or body who, at the time when the approval was applied for, was entitled to the benefit of any registered interest affecting the land or, as the case may be, the part to be surrendered (including a charge of any lease or sublease);

(b) any person or body having at that time a lien over the said land or part, or over any lease or sublease thereof;

(c) any person or body entitled at that time to the benefit of any tenancy exempt from registration affecting the said land or part, being a tenancy protected by an endorsement on the register document of title; and

(d) any person or body having at that time a claim protected by caveat affecting the said land or part or any interest therein.

(3) No surrender of a part only of any alienated land shall be approved if, in the opinion of the State Director or, as the case may be, Land Administrator, the area of the part is such that a subdivision of the land ought first to be effected.

Applications for approval of surrender of part.

200(1) Any application for approval by a proprietor wishing to surrender a part only of the land comprised in his title shall be made in writing to the Land Administrator in Form 12B, and shall be accompanied by-

(a) such fee as may be prescribed;

(b) a plan showing the details of the proposal, together with such number of copies thereof as may be prescribed or, in the absence of any such prescription, as the Land Administrator may require;

(c) all such written consents to the making of the application as are required under paragraph (c) of sub-section (1) of s 196; and

(d) subject to sub-section (3), the issue document of title to the land.

(2) Upon receiving any such application, the Land Administrator shall endorse, or cause to be endorsed, a note thereof on the register document of title to the land.

(3) An application under sub-section (1) may be submitted without the issue document of title if that document is in the hands of any person as chargee, or has been deposited with any person as security for a loan; but in any such case, the application shall be accompanied instead by a copy of a request by the proprietor, served on that person under sub-section (2) of s 244 or, as the case may be, sub-section (4) of s 281, for the production of the document at the Land Office within fourteen days of the date thereof.

(4) In a case falling within sub-section (3), no action shall be taken on the application until the issue document, or a replacement thereof, is in the hands of the Land Administrator; and accordingly, if the document is not produced pursuant to the request referred to in that sub-section, or to any notice served under s 15 on default in compliance with the request, title in continuation (or, where appropriate, a duplicate issue document only) shall be prepared under Chapter 3 of Part Ten as if the circumstances were as specified in paragraph (c) of sub-section (1) of s 166.

Procedure on applications.

201(1) Where any application under sub-section (1) of s 200 relates to land the surrender of which requires the approval of the State Director, the Land Administrator shall refer the application to him, together with his recommendations thereon.

(2) If on any application under the said sub-section the Land Administrator or, in a case referred to him as aforesaid, State Director is satisfied-

(a) (Deleted by Act A832).

(b) that the conditions specified in sub-section (1) of s 196 are fulfilled, and

(c) that approval ought not to be withheld on the grounds specified in sub-section (3) of that section,

he shall approve the surrender.

(3) In any other case, the Land Administrator or, as the case may be, State Director shall reject the application.

(4) On approving, or being informed by the State Director that he has approved, the surrender, the Land Administrator shall-

(a) revise (by reference to the estimated area of the part to be retained) the rent payable by the proprietor;

(b) notify the proprietor of the approval and the revised rent; and

(c) make, or cause to be made, a memorial of the surrender on the register and issue documents of title to the land.

(5) On rejecting, or being informed by the State Director that he has rejected, the application, the Land Administrator shall-

(a) notify the proprietor; and

(b) cancel, or cause to be cancelled, the note endorsed on the register document of title pursuant to sub-section (2) of s 200.

[48] The procedure for land acquisition and the relevant provisions of the LAA in respect of this appeal are as follows.

[49] Section 7 of the LAA provides that when any lands are required for any purposes as stated in s 3 of the LAA the Land Administrator shall prepare and submit to the State Authority the following:

(a) a plan of the whole area of such lands, showing the particular lands, or parts thereof, which it will be necessary to acquire; and

(b) a list of such lands, in Form C.

[50] Section 8 LAA provides that when the State Authority decides that any of the lands referred to in s 7 are needed for any of the purposes referred to in s 3 LAA then a declaration in Form D as prescribed shall be published in the Gazette. The declaration in Form D shall be conclusive evidence that all the scheduled land referred to therein is needed for the purpose specified therein.

[51] Section 8(4) LAA further stipulates that a declaration under subsection (1) shall lapse and cease to be of any effect on the expiry of two years after the date of its publication in the Gazette in so far as it relates to any land or part of any land in respect of which the Land Administrator has not made an award under subsection 14(1) of the same Act within the said period of two years. All proceedings already taken or currently being taken in consequence of such a declaration in respect of such land or such part of the land shall terminate and be of no effect.

[52] The proposed land to be acquired must be marked out and a notice must be entered on the register document of title as required under s 9 LAA:

(1) Upon the publication pursuant to s 8 of the declaration in Form D that any land is needed for the purpose specified in such Form, then-

(a) the Land Administrator shall cause the areas affected by the acquisition to be marked out upon the land, unless this has already been done to his satisfaction; and

(b) the Land Administrator or other registering authority shall make a note of the intended acquisition in the manner specified in subsection (2).

(2) The note of the intended acquisition required by para (1)(b) shall be made-

(a) where the scheduled land is held by registered title-

(i) on the register document of title; and

(ii) in the case of land with subdivided building or land, on the relevant strata register under s 4 of the Strata Titles Act 1985 [Act 318]; or

(b) where the scheduled land is occupied in expectation of title, upon the Register of Approved Applications, Register of Holdings or other appropriate register.

[53] Under the LAA the Land Administrator must conduct an enquiry. Section 12 LAA reads as follows:

(1) On the date appointed under of subsection 10(1) the Land Administrator shall make full enquiry into the value of all scheduled lands and shall as soon as possible thereafter assess the amount of compensation which in his opinion is appropriate in each case, according to the consideration set out in the First Schedule:

Provided that the Land Administrator may obtain a written opinion on the value of all scheduled lands from a valuer prior to making an award under s 14.

(2) The Land Administrator shall also enquire into the respective interests of all persons claiming compensation or who in his opinion are entitled to compensation in respect of the scheduled land, and into the objections, if any, made by any interested person to the area of any scheduled land.

(3) The Land Administrator may for a sufficient cause to be recorded by him in writing postpone any enquiry or adjourn any hearing of an enquiry from time to time.

(4) The Land Administrator shall record all the evidence during the enquiry.

[54] Reference to Court by the Land Administrator is provided under s 36 LAA:

(1) No reference to Court under this Act shall be made otherwise than by the Land Administrator.

(2) The Land Administrator may, at any time of his own motion by application in Form M refer to the Court for its determination any question as to-

(a) the true construction or validity or effect of any instrument;

(b) the person entitled to a right or interest in land;

(c) the extent or nature of such right or interest;

(d) the apportionment of compensation for such right or interest;

(e) the persons to whom such compensation is payable;

(f) the costs of any enquiry under this Act and the persons by whom such costs shall be borne.

(3) Without prejudice to the powers of the Court under this Part, the costs of any reference under subsection (2) shall be borne by such person as the Court may direct or, in the absence of such direction, by the Land Administrator.

(4) After an award has been made under s 14 or compensation made under s 35 or Part VII the Land Administrator shall refer to the Court for determination any objection to such award or compensation duly made in accordance with this Part.

[55] Section 37 LAA reads as follows:

Any person interested in any scheduled land who, pursuant to any notice under s 10 or 11 or any person interested pursuant to any compensation made under s 35 or Part VII who, has made a claim to the Land Administrator in due time and who has not accepted the Land Administrator's award thereon, or has accepted payment of the amount of such award under protest as to the sufficiency thereof, may, subject to this section, make objection to-

(a) the measurement of the land;

(b) the amount of the compensation;

(c) the persons to whom it is payable;

(d) the apportionment of the compensation.

[56] Any objection made under s 37 shall be made by a written application in the prescribed Form N to the Land Administrator requiring that he refer the matter to the Court for its determination. Such application shall state fully the grounds on which objection to the award is taken, and at any hearing in Court no other grounds shall be given in argument, without leave of the Court (Re: Section 38(1) LAA).

[57] In respect of appeal, s 49 LAA provides as follows:

"(1) Any person interested, including the Land Administrator and any person or corporation on whose behalf the proceedings were instituted may appeal from a decision of the Court to the Court of Appeal and to the Federal Court:

Provided that where the decision comprises an award of compensation there shall be no appeal therefrom."

Factual Background

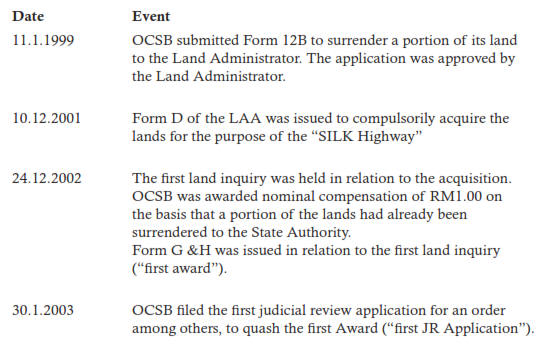

[58] OCSB decided to surrender part of its land and submitted an application vide the prescribed Form 9A dated 5 September 1998 to surrender a portion of land to the Land Administrator of Hulu Langat District pursuant to s 200 of the NLC for construction of "Jalan, Simpanan Parit JPS, Kolam Takungan Air JPS, Taman Bandar, Tempat Letak Kereta, Buffer Zone" by filing the prescribed Form 12B as required by the law. The construction of the road and others were necessary as part of a commercial development project known as "Pusat Dagangan Putra Kajang". OCSB is the owner and developer of the said project. The application was approved by the State Authority on 11 January 1999.

[59] Subsequently, on 10 December 2001 Form D as prescribed under the LAA was issued to OCSB by the Government to compulsorily acquire the lands held under Lots 8630 (9.005.08 sqm) and 2630 (10,118.69 sqm), Geran No: 30006 in Mukim Kajang, District of Hulu Langat, Selangor Darul Ehsan (the Lands) belonging to OCSB to construct the Kajang Traffic Dispersal Highway (SILK Highway). A total of 19,123.77 sqm of land was acquired. The Selangor State Authority published in the Selangor Government Gazette dated 20 December 2001 Form D pursuant to s 8 of the LAA 1960 declaring that the Lands would be acquired for public purpose.

[60] The first land inquiry was held on 24 December 2002 about the acquisition (1st Land Inquiry). OCSB was awarded nominal compensation of RM1.00 (1st Award) on the basis that a portion of the Lands had already been surrendered by OCSB to the State Authority. Form G and Form H dated 24 December 2002 were issued in relation to the first land inquiry.

[61] On 30 January 2003 OCSB filed the first judicial review application for an order, among others, to quash the 1st Award and a declaration that the acquisition of the Lands was null and void (1st JR Application). In its application, OCSB alleged that it was not given a right to be heard at the first land inquiry. The Lands had already been formally taken possession of when Form K was issued on 20 February 2003 in accordance with s 22 of the LAA 1960. The memorial was endorsed in the register document of title after the issuance of Form K.

[62] The 2nd Land Inquiry was subsequently held by the Land Administrator on 17 February 2011, and on 20 April 2012 the Land Administrator ordered as follows:

(a) 17,284.67 square meters of the Land have been surrendered by OCSB to the State Authority (Surrendered Area). The Land Administrator awarded nominal compensation of RM10.00 for the Surrendered Area; and

(b) 1,839.10 square meters of the Lands were not surrendered and the Land Administrator awarded compensation of RM514,948.00 (the 2nd Award).

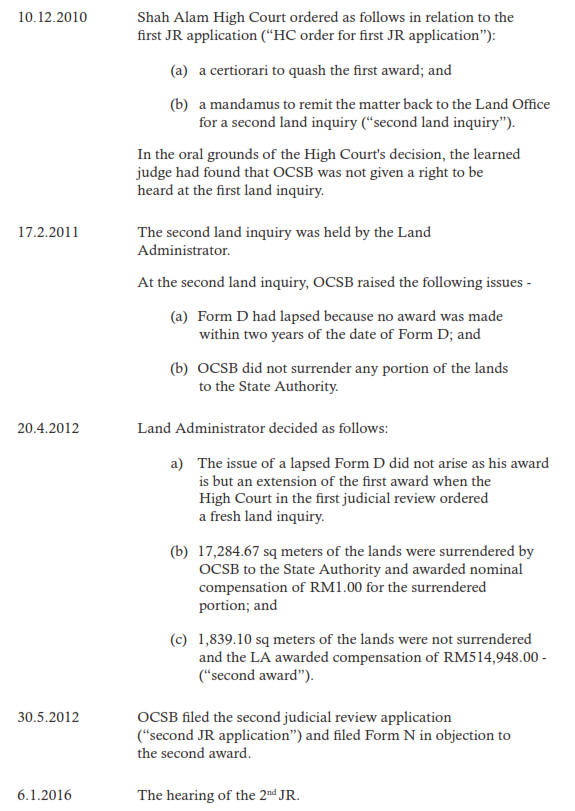

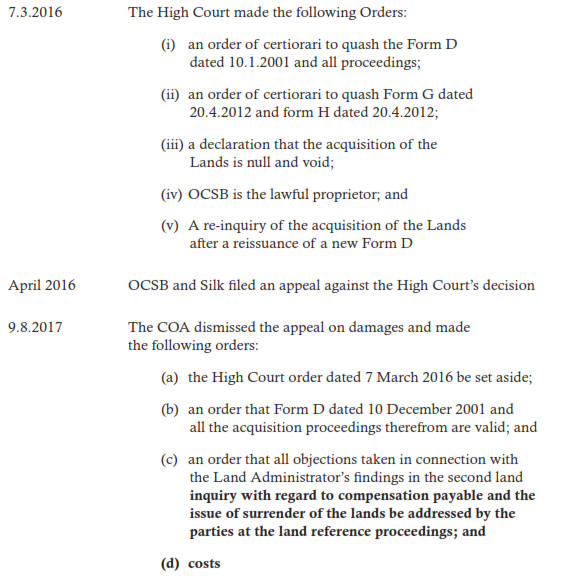

[63] The 2nd Award replaced the 1st Award, as ordered by the High Court in the 1st JR Application. Unhappy with the Land Administrator's decision, OCSB filed a second judicial review against the Land Administrator, Director of the Department of the Director-General of Lands and Mines State of Selangor, Government of the State of Selangor and Government of Malaysia (the 2nd JR Application). Both OCSB and Sistem Lingkaran Lebuhraya Kajang Sdn Bhd (SILK) filed Form N objecting to the 2nd Award on 31 May 2012. The land reference proceedings in Form N filed by both OCSB and SILK were consolidated and stayed until the final disposal of the 2nd JR Application. SILK applied to, among others, intervene in the 2nd JR Application ("SILK's Intervening Application") and on 19 August 2013 SILK's application was allowed. The hearing of the 2nd JR Application was heard on 6 January 2016 and on 7 March 2016 the High Court made the following orders:

(a) an order of certiorari to quash a Form D dated 10 December 2001 issued pursuant to s 8(1) of the LAA 1960 and all proceedings following therefrom for the acquisition of the Lands belonging to Orchard Circle;

(b) an order of certiorari to quash Form G dated 20 April 2012 and Form H dated 20 April 2012 issued pursuant to ss 14(1) and 16(1) of the LAA 1960 and all proceedings therefrom;

(c) a declaration that-

(i) the acquisition or taking into possession of the Lands by the respondents is null and void and of no legal effect; and

(ii) OCSB is the lawful proprietor of the Lands and it is entitled to possession thereof;

(d) A re-inquiry of the acquisition of the Lands is ordered after reissuance of a new Form D.

[64] SILK and the other respondents appealed to the Court of Appeal against part of the decision of the High Court. OCSB appealed to the Court of Appeal against part of the decision of the High Court. OCSB also filed a cross-appeal. Given the appeals, the land reference proceedings were stayed pending the disposal of the appeals and cross-appeal to the Court of Appeal by way of a consent order dated 24 May 2016.

[65] The Court of Appeal unanimously allowed SILK and the other respondents' appeals, dismissed OCSB's appeals, and ordered that the HC Order for the 2nd JR Application be set aside.

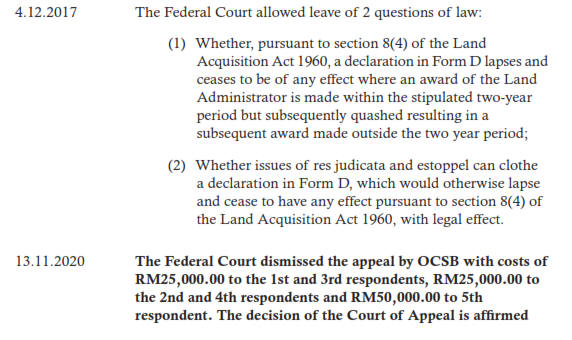

[66] OCSB proceeded to apply for leave to appeal to the Federal Court on 17 August 2017. The land reference proceedings were stayed pending the final disposal of OCSB's appeal to the Federal Court by way of an order dated 3 November 2017. On 4 December 2017, the Federal Court allowed leave of the following two questions:

(a) whether, pursuant to s 8(4) of the LAA 1960, a declaration in Form D automatically lapses and ceases to be of any effect where an award of the Land Administrator is made within the stipulated two-year period but subsequently quashed resulting in a subsequent award made outside the two-year period; and

(b) whether the issues of res judicata and estoppel can clothe a declaration in Form D, which would otherwise lapse and cease to have any effect pursuant to s 8(4) of the LAA 1960, with legal effect.

[67] The Federal Court opined that OCSB had benefitted from the 1st judicial review, the effect of which the first award was quashed (certiorari) and proceeded with a second land inquiry (mandamus) whereby OCSB participated. The order for mandamus by the 1st Judge of the High Court (Hinshawati Shariff J) concluded that Form D was still valid. Hence, OCSB was precluded and estopped from challenging the validity of Form D in the 2nd judicial review application. By proceeding with the second land inquiry before the Land Administrator and participating in the enquiry, OCSB had elected and accepted that the issue before the Land Administrator was on the decision and award of compensation and damages only. That was the position taken by OCSB after the 1st judicial review proceeding. Thus, the doctrine of estoppel applied in this case.

[68] The validity of the acquisition proceedings and whether OCSB was still the lawful proprietor of the said lands were previously raised in the 1st judicial review application before the COA. The COA opined that it would be an abuse of the court process to allow OCSB to renew its challenge on the propriety of the land acquisition proceedings in the second judicial review proceeding as the issues raised were caught by the doctrine of res judicata.

[69] The second question as framed did not appear to flow from the facts of the case. The applicability of the doctrine of estoppel and res judicata was an election made by OCSB in the conduct of litigation, which was peculiar. There was no issue of Form D lapsing because the original Form D was still valid even during the second land inquiry. The doctrine of estoppel and res judicata was not applied to override s 8(4) of the LAA as there was no contravention of that particular provision in the first place because the first award was made within two years. These issues ought to have been raised in the first judicial review application, in which the issues or matter had been decided in finality.

[70] The Federal Court affirmed the decision of the COA which had ordered that all objections taken in connection with the Land Administrator's findings in the second land inquiry with regard to compensation payable and the issue of surrender of the lands be addressed by the parties at the land reference proceedings before the High Court Judge.

The High Court

[71] The High Court considered and addressed the issue of surrender of the lands. The learned High Court Judge concluded that there was a proper surrender of land prior to the land being acquired. Her Ladyship explained in her grounds of judgment:

"[34] In the considered view of this court, it does not matter that the SILK Highway only came into being after OC had surrendered the land. This is because the fact of the matter remains that OC had already surrendered the land. While it was argued by OC that the surrendered portion was used for the SILK Highway, this court is of the considered view that regardless of whether the surrendered portion was used for SILK Highway or not, the surrendered portion still falls within the ambit of public utility as opposed to private usage. The use of the SILK Highway, in the view of this court is clearly not for private usage.

.....

[38] In the case before this court, since Form 12B was signed and submitted by OC in compliance with s 200 of the NLC and the Land Office approved the surrender. In the view of this court, even without OC surrendering their original title so in order for endorsement to be made, the surrender is still effective.

[40] Founded on the authority quoted and the facts of this case, even though there was no endorsement on the title, this court is of the considered view the surrender has happened. The endorsement on the title could not be carried out as OC did not surrender the original title to the land office for the purpose of endorsement. In the view of this court, this does not negate the fact that there was a surrender prior to SILK concessionaire coming into the picture"

The Court Of Appeal

[72] Aggrieved with the decision of the High Court, OCSB appealed to the Court of Appeal. Only one issue for determination is whether a total of 17,284.67 square metres (which is the Surrendered Area) out of 19,123.77 square metres of the subject land for acquisition, namely Lot 2630 and Lot 8630 (the subject land), had or had not been surrendered to the State Authority according to the NLC under Part Twelve which deals with the surrender of title as at 20 December 2001.

[73] The COA concluded that the surrender of the impugned land could only be construed as effected upon the compliance of s 201(4)(a) to (c) of the NLC. The word "shall" connote a mandatory obligation on the part of the Land Administrator to comply with the requirements under the aforesaid section. In this present case, there was no revision of the payable rent, no notification to the appellant of the approval and any revised rent and no memorial of the surrender was made on the register and issue documents of title to the impugned land on or before 2 December 2001, the date of the Gazette or 10 December 2001, the date stipulated in Form D.

[74] The COA agreed with OCSB that since the provisions of the NLC were not adhered to and there was no plan showing the details of the proposed surrendered land and the delivery of the issue document of title as required under the provisions in the NLC grave doubt is therefore cast on the validity of the surrender on 11 January 1999.

[75] The COA opined that the approach taken by the High Court for the compensation in relation to the Surrendered Area on the basis that the land had already been surrendered was not correct and hence, the High Court fell into error of law in accepting that the Surrendered Area could not be assessed because it had already been surrendered. The COA opined that the fact that the impugned land was originally intended to be surrendered for the purpose of the appellant's development project would be a relevant factor to be considered in determining the land value in the assessment of the compensation amount.

Analysis And Decision

[76] For ease of reference, the salient chronological background of this appeal is summarised as follows:

[77] The main argument advanced by OCSB as a respondent in the COA is that the State Authority failed to comply with the provisions of Part Twelve of the NLC. Such non-compliance would render the surrender of the Surrendered Area on 11 January 1999 invalid for the purpose of assessment of compensation upon land acquisition. It is OCSB's contention that the Surrendered Area was never surrendered because the provision of the NLC was not complied with when Form D dated 10 December 2001 was published in the Gazette on 20 December 2001. The Land Administrator, as well as the High Court Judge, were wrong to find that OCSB had surrendered the impugned land before the Gazette was published. Further, the Land Administrator's award of only a nominal sum of RM10.00 as the compensation award for the impugned land which was affirmed by the High Court was erroneous in law.

[78] In its judgment, the COA reasoned as follows:

"(a) In respect of the non-compliance with s 201(4) of the NLC on or before 10 December 2001 (the date of Form D) or 20 December 2001 (the date of Gazette):

[26] This court is of the considered view that the surrender of the impugned land could only be construed as effected upon the compliance of s 201(4)(a) to (c) of the NLC. The word "shall" connotes a mandatory obligation on the part of the Land Administrator to comply with the requirements in s 201(4)(a) to (c) of the NLC. In this present case, there was no revision of the payable rent, no notification to the appellant of the approval and of any revised rent and no memorial of the surrender was made on the register and issue documents of title to the impugned land on or before 20 December 2001 (the date of the Gazette) or 10 December 2001 (the date in the Borang D).

(b) The Court of Appeal referred to the case of Bayangan Sepadu Sdn Bhd v. Jabatan Pengairan Dan Saliran Negeri Selangor & Ors [2022] 2 MLRA 1 where the Federal Court held that the failure to comply with the relevant provisions in the NLC, particularly s 201(4)(a) to (c), could result to grave doubt being cast on the validity of the surrender on 11 January 1999:

[34] In Bayangan Sepadu Sdn Bhd v. Jabatan Pengairan Dan Saliran Negeri Selangor & Ors [2022] 2 MLRA 1, one of the questions of law posed before the apex court, which is relevant to our case, was "whether there was a valid surrender of any part of the land to the State Authority under s 196(1)(c) read with s 196(2)(a) of the NLC when the chargee's consent to the same had not been obtained.

[35] One of the reasons the apex court allowed the appeal was that the provisions in the NLC in relation to the surrender of the land were not strictly adhered to. In our present case, failure to comply with the relevant provisions in the NLC, particularly s 201(4)(a) to (c), could result in grave doubt being cast on the validity of the surrender on 11 January 1999.

[36] This court also finds that there were provisions of the NLC other than s 201(4) that were not adhered to. There was no plan showing the details of the proposed surrender land (specifically the impugned land) and the delivery of the issue document of title as required under s 200(1) (b) and (d) of the NLC, and read together with sub-sections (3) and (4) of the same provision.

[37] The approach taken by the High Court for the compensation in relation to the impugned land was on the basis that the impugned land had already been surrendered. Hence, this court finds the High Court fell into error of law in accepting that the impugned land could not be assessed because it had already been surrendered.

[38] This court further finds that the fact that the impugned land was originally intended to be surrendered for the purpose of the appellant's development project would be a relevant factor to be considered in determining the land value in the assessment of the compensation amount.

[39] This court opines that whether the impugned land would have any commercial value because it was intended to be surrendered for the appellant's development project ought to be determined by the High Court Judge assisted by the assessors. This issue was not considered by the High Court Judge because the High Court Judge dismissed it on the footing that the impugned land had already been surrendered.

(c) Since there was no plan showing the details of the proposed surrender of land and delivery of the issue document of title as required under s 200(1)(b) and (d) of the NLC read together with s 200(3) and (4) of the same. The High Court erred in accepting that the Surrendered Portion could not be assessed as the approach taken by the High Court for the compensation was on the basis that the Surrendered Area had already been surrendered.

Question Of Law v. Question Of Fact

[79] The starting point to address is whether the complaint with regard to the formalisation of the surrender of the Surrendered Area raised by OCSB is a question of law or otherwise. This issue is important as it has a determinative effect on whether OCSB has the right to appeal as envisaged under s 49 LAA. Section 49 LAA prohibits any appeal in respect of compensation. The COA opined that the finding of whether the procedure for surrender of the impugned land had or had not been complied with is a question of fact. However, the finding of when the surrender of the impugned land took effect is a question of law. Hence it was concluded by the COA that to determine the validity of the surrender, "....it is inevitable that the exercise has to encroach onto the former." In other words, the question raised by OCSB contains a mixture of both fact and law.

[80] Amitabha Guha & Anor v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat [2021] 2 MLRA 19 laid down guidelines to be applied in determining whether an issue raised in land acquisition matter is a question of law or not:

"In a general sense, a question of law is an issue involving the interpretation of law (statutes or legal principles) and the application of the law to the facts of each individual case. What is a question of law has also been discussed and formulated in a line of cases:

(i) questions of law are questions about what the correct legal test is. Questions of mixed law and fact are questions about whether the facts satisfy the legal tests: Canada (Director of Investigation and Research v. Southam Inc [1997] 1 SCR 748);

(ii) a question of law is a question concerning the legal effect to be given to a set of undisputed facts. This includes an issue which involves the application or interpretation of a law (Carrier Lumber Ltd v. Joe Martin & Sons Ltd [2003] BCJ No 1602);