Federal Court, Putrajaya

Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat CJ, Nallini Pathmanathan, Nordin Hassan FCJJ

[Civil Appeal No: 01(f)-16-04-2024(W)]

3 March 2025

Professions: Medical practitioners — Rights of — Respondents sought declarations on certain rights respondents said they and other registered medical practitioners had under law — Whether declarations sought impeded or interfered with any criminal investigations — Whether registered medical practitioners could sell (either by retail or wholesale) and/or dispense for purposes of consumption/administration by their human patients Ivermectin (in whatever form) which was not a 'registered product' and without a licence for that purpose under scheme enacted in Poisons Act 1952 and Sale of Drugs Act 1952 and their respective Regulations

The core issue in this appeal concerned the interpretation of certain provisions in the Poisons Act 1952 ('Act 366') and the Poisons Regulations 1952 ('1952 Regulations'), as well as the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 ('Act 368') and its regulations, namely, the Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 ('1984 Regulations'). The main leave question, ie Leave Question 1 (among the leave questions granted) was whether the legal principles enunciated in Datuk Syed Kechik Syed Mohamed v. Government of Malaysia & Anor ('Syed Kechik') and YAB Dato' Dr Zambry Abd Kadir & Ors v. YB Sivakumar Varatharaju Naidu; Attorney General Malaysia (Intervener) ('Zambry') applied to situations or circumstances involving substantial issues or grievances regarding pending criminal investigations, criminality, criminal charges and the prosecutorial discretion of the Public Prosecutor. In this case, an investigating officer from the Selangor Pharmaceutical Services Division had entered the 2nd respondent's clinic and purchased a box of Ivermectin Verpin-12 tablets from its assistant. As soon as the sale was completed, officers from the same department entered the clinic and confiscated the tablets and capsules ('Search and Seizure'), which were said to be Ivermectin medicines ('Ivermectin'). Dissatisfied with the Search and Seizure, the respondents jointly filed an Originating Summons ('OS') seeking declarations on certain rights allegedly possessed by them and other registered medical practitioners under the law. Both parties accepted that no criminal proceedings had been instituted against the 1st respondent as of the filing date of the OS. However, the appellants confirmed that after the OS was filed, a criminal charge had been preferred against the 2nd respondent. The High Court Judge ('Judge') found that the declarations sought by the respondents impeded or interfered with possible criminal investigations that might be brought against the 2nd respondent. The Judge concluded that the OS was an abuse of process and frivolous. The Court of Appeal, however, held that the Judge erred in his assessment of the case; that the OS was not brought with a collateral purpose of interfering with the criminal investigations brought against the 2nd respondent; and that the Judge had failed to appreciate the Federal Court judgment in Syed Kechik. The Court of Appeal accepted the respondents' contention that Syed Kechik was the authority for the proposition that a declaration of rights of a party could be requested from the Courts before the occurrence of the event that the party was trying to avoid. Hence, the main issue to be considered was whether registered medical practitioners could sell (either by retail or wholesale) and/or dispense Ivermectin (in any form) for purposes of consumption/administration by their human patients despite it not being a 'registered product' and without a licence for that purpose under the legislative framework established by Acts 366 and 368 and their respective 1952 and 1984 Regulations. The facts in this OS also gave rise to two additional issues. The first issue concerned the legal tenability of the nature of the declarations sought in this case and whether they could be granted in light of the doctrine of separation of powers. The second issue was whether the declarations, if granted, would be tantamount to judicial interference with the executive and legislative policy by effectively accepting Ivermectin as a suitable treatment option or preventive measure for COVID-19.

Held (dismissing the appeal):

(1) The Court of Appeal held that the decisions of Syed Kechik and Zambry applied to the respondents, mainly the 2nd respondent, because he was seeking declarations on his position and rights under Act 366. It had been the respondents' principal stance from day one that they were only subject to Act 366 and the 1952 Regulations in their dispensation of Ivermectin for the treatment of their patients and that they were not subject to Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations. As such, they submitted that the declarations were not designed to impede or interfere with criminal investigations against the 2nd respondent but rather, it was for them and all registered medical practitioners to know their rights and legal position. The Court accepted the respondents' argument and the decision of the Court of Appeal as entirely correct on the facts. As such, the High Court was erroneous in holding that the respondents were attempting to interfere with the criminal investigations to the extent of the relief prayed for in the Declarations. (paras 68-70)

(2) The respondents did not challenge the legality of the Search and Seizure, nor did they ask for any relief to the effect that the 2nd respondent ought not to be prosecuted or that he had not committed any offence. The 1st respondent, also representing a body of qualified specialists and doctors, had the right to determine the legal extent of doctors' rights to dispense Group B poisons and whether such rights were limited by Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations. The nature of the relief sought in this case was purely to move the Court to exercise its most basic functions of judicial interpretation to determine the state of the law as regards Acts 366 and 368 and their respective Regulations. The law was settled beyond any dispute that only Courts could make determinative findings of factual and legal rights. While it remained the Public Prosecutor's sole right to charge any person for an offence, such a power was exercised in accordance with written law. Where the law was unclear, only Courts could determine the interpretation of that law or rule. The final determination would then serve the effect of putting parties on notice on exactly where they stood in terms of their present and future rights as determined in Syed Kechik. (paras 71-73)

(3) While Syed Kechik and Zambry did not on their facts concern the grant of declarations pending criminal charges or investigations, their collective ratio decidendi extended to and applied mutatis mutandis to cases, such as this one, in which the persons affected sought to clarify or determine their legal rights or position. The declarations sought by the respondents did not impede or interfere with any criminal investigations but would assist them in clarifying their legal rights vis-à-vis Acts 366 and 368 and their attendant Regulations. Further, ss 18, 19 and 21 of Act 366 specifically contained procedures and principles that governing registered medical practitioners must follow and to the extent that related criminal investigations remained open and unimpeded. The Court of Appeal was thus correct in reversing the High Court's finding that such declarations were an abuse of process or frivolous and/or vexatious. Consequently, Leave Question 1 was answered in the affirmative. (paras 87-90)

(4) Ivermectin was classified as a Group B poison in the First Schedule of Act 366 (and it was therefore not a Group A poison). Hence, it would follow as per s 19(1)(a) of Act 366 that a registered medical practitioner could sell, supply or administer Ivermectin to his or her patients for their treatment, solely by virtue of being a registered medical practitioner. Therefore, under s 19 of Act 366, and having regard to the scheme of that Act, the 2nd respondent, like all other registered medical practitioners, was allowed by law to dispense Ivermectin to his patients provided that such dispensation was only for treatment purposes. The 1952 Regulations had little bearing on this interpretation because the rights to dispense (sell or supply) and administer Ivermectin as a Group B poison were substantively determined by Act 366 as the parent or primary legislation to the 1952 Regulations. Further, the 1952 Regulations primarily dealt with technical matters such as storing, labelling, packaging and importation of poisons, rather than the substantive rights of registered medical practitioners which were regulated expressly by ss 19 and 21 of Act 366. (paras 107-109)

(5) Act 366 positively asserted a right vested in ss 18, 19 and 21 to registered medical practitioners to sell, supply and administer Group B poisons to their patients for their treatment only and specifically enumerated those poisons (and their manner of preparations) patently in the First Schedule, while Act 368 appeared to disregard such mechanism, as it was entirely silent on the rights of registered medical practitioners to supply 'drugs' (as opposed to expressly enumerated 'poisons') and what exactly could ostensibly be ascertained as 'drugs' in the absence of any expressly enumerated provisions in Act 368. Accordingly, Act 368 was inapplicable to the respondents' right to dispense Ivermectin as per ss 18, 19 and 21 of Act 366. Likewise, the 1984 Regulations, as subsidiary legislation under Act 368, had no bearing as it could neither grant nor remove rights conferred by primary legislation such as Act 366. (paras 135-138)

(6) Throughout the proceedings, the appellants had not once disputed the interpretation of the relevant provisions in Act 366 in the manner advanced by the respondents. Their sole substantive suggestion was that while such rights existed in Act 366, these rights were subject to the requirement that the drug must first be a registered product under the 1984 Regulations. For the reasons stated above, the Court could not agree with such a constrained reading of the applicable provisions and consequently, the Court of Appeal was correct to reverse the High Court's findings. (paras 148-149)

(7) This case was not related to the efficacy of Ivermectin vis-à-vis COVID-19 but rather focused on the substantive right of the respondents and other registered medical practitioners to dispense the same to their patients solely for treatment purposes as per Act 366. The Court was only concerned with the interpretation of the provisions of Act 366 and its 1952 Regulations as against the application of Act 368 and its subsidiary legislation in the 1984 Regulations. All things considered, it was not the Courts but Act 366 (properly interpreted) that granted the right to registered medical practitioners to dispense Ivermectin as a Group B poison and if they continued to do so in accordance with Act 366, even if for the treatment/prevention of COVID-19, this occured because of the appellants' failure to enforce more suitable legal mechanisms to curb the practice, pending any proper determination of Ivermectin's ability to treat or prevent COVID-19 as the respondents and others like them claimed it could. To the extent that the appellants suggested that they could rely on Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations to disallow the dispensation of Ivermectin under Act 366, the Court did not agree with that interpretation - and this had no bearing on any Government policy of Ivermectin as a drug/medicine/ingredient itself. (paras 159, 167 & 168)

Case(s) referred to:

Ang Ming Lee & Ors v. Menteri Kesejahteraan Bandar Perumahan Dan KerajaanTempatan And Anor And Other Appeals [2019] 6 MLRA 494 (refd)

Athavle v. New South Wales [2021] FCA 1075 (distd)

Clarence Ng Chii Wei & Ors v. Menteri Kesihatan & Ors [2022] 1 MLRH 262 (distd)

YAB Dato' Dr Zambry Abd Kadir & Ors v. YB Sivakumar Varatharaju Naidu; Attorney-General Malaysia (Intervener) [2009] 1 MLRA 474 (folld)

Datuk Syed Kechik Syed Mohamed v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [1978] 1 MLRA 504 (folld)

Empayar Canggih Sdn Bhd v. Ketua Pengarah Bahagian Penguatkuasa Kementerian Perdagangan Dalam Negeri Dan Hal Ehwal Pengguna Malaysia & Anor [2015] 1 MLRA 341 (refd)

Government of Malaysia v. Lim Kit Siang & Another Case [1988] 1 MLRA 178 (refd)

Kassam And Others v. Hazzard And Others [2021] 393 ALR 664 (distd)

Lai Soon Onn v. Chew Fei Meng & Other Appeals [2018] 6 MLRA 633 (refd)

Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai & Anor v. Muziadi Mukhtar [2019] 2 MELR 1; [2019] 2 MLRA 485 (refd)

SD v. Royal Borough Of Kensington And Chelsea [2021] EWCOP 14 (distd)

Tan Sri Haji Othman Saat v. Mohamed Ismail [1982] 1 MLRA 496 (refd)

Tey Por Yee & Anor v. Protasco Bhd & Other Appeals [2020] MLRAU 69 (refd)

Tengku Jaffar Tengku Ahmad v. Karpal Singh [1993] 2 MLRH 558 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Control of Drugs And Cosmetics Regulations 1984, rr 7(1)(a), (b),15(2)(c)

Federal Constitution, art 145(1)

Poisons Act 1952 , ss 2, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11,12(1)(c), 13, 15, 16, 17, 18(1)(c), 19(1)(a), 20, 21(1), (2), 22, 23, 26(1), First Schedule

Sale of Drugs Act 1952, ss 2, 12

Counsel:

For the appellants: Rahazlan Affandi Abdul Rahim (Liew Horng Bin & Saravanan Kuppusamy with him); AG's Chambers

For the respondents: Gurdial Singh Nijar (Abraham Au Tian Hui & Lim Sze Han with him); M/s Yeoh Mazlina & Partners

[For the Court of Appeal judgment, please refer to Dr Vijaendreh Subramaniam & Anor v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [2024] 6 MLRA 67]

JUDGMENT

Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat CJ:

Introduction

[1] The core issue in this appeal concerns the interpretation of certain provisions in the Poisons Act 1952 [Act 366] and the Poisons Regulations 1952, as well as the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 [Act 368] and its regulations, namely the Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984. We shall respectively refer to them as Act 366, the 1952 Regulations, Act 368, and the 1984 Regulations.

[2] The six questions upon which leave was granted ('Leave Questions'), are these:

"Leave Question 1

Whether the legal principles enunciated in Datuk Syed Kechik Syed Mohamed v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [1978] 1 MLRA 504 and YAB Dato' Dr Zambry Abd Kadir & Ors v. YB Sivakumar Varatharaju Naidu; Attorney-General Malaysia (Intervener) [2009] 1 MLRA 474 apply to the situations or circumstances or cases where there are substantial issues or grievances regarding pending criminal investigation, criminality, criminal charges and prosecutorial discretion of the Public Prosecutor?

Leave Question 2

In the circumstances where the disputes canvassed by the applicant is on the registered medical practitioners' right to dispense Ivermectin to patients for the specific purpose of pandemic COVID-19 treatment, is it apt for the Court to only rely on the provisions of the Poisons Act 1952 [Act 366] and Poisons Regulations 1952 [1952 Regulations] and disregard the provisions of the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 [Act 368] and Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 [1984 Regulations] in determining whether a registered medical practitioner is entitled to dispense Ivermectin to patients for the purpose of prophylaxis and / or medical treatment?

Leave Question 3

In the circumstances where at present, no product with Ivermectin as an active ingredient has been registered with the Drug Control Authority for human use and that it is the policy of the Government on the prohibition of Ivermectin for COVID-19 treatment, whether it is apt for the Court to directly or indirectly permit the use of an unregistered poison like Ivermectin including and not restricted to the treatment of COVID-19 which was contrary to the regulatory regime and framework of the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 [Act 368], Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 [1984 Regulations], Poisons Act 1952 [Act 366] and Poisons Regulations 1952 [1952 Regulations]?

Leave Question 4

In the circumstances where to date, it is the Government's policy that the use of unregistered Ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 is only permitted for the purpose of clinical trials subject to the approval of the Ministry of Health which is then in line with the guidance of the World Health Organisation (WHO) and that clinical trials to establish the efficacy and effectiveness of Ivermectin in this regard have yet to be concluded, whether it is apt for the Court to directly or indirectly permit the use of an unregistered poison like Ivermectin including and not restricted to the treatment of COVID-19 which was contrary to the regulatory regime and framework of the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 [Act 368], Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 [1984 Regulations], Poisons Act 1952 [Act 366] and Poisons Regulations 1952 [1952 Regulations]?

Leave Question 5

In the circumstances where the pandemic of COVID-19 gave rise to a public health emergency at a national and global level and that policy measures in respect of COVID-19 must necessarily be highly flexible, adapted based on every new development in scientific and medical knowledge, based on the collective experience of the world in dealing with a novel and deadly virus, whether it is apt for the Court to directly or indirectly permit the use of an unregistered poison like Ivermectin including and not restricted to the treatment of COVID-19 which was contrary to the regulatory regime and framework of the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 [Act 368], Control of Drugs and Cosmetic Regulations 1984 [1984 Regulations], Poisons Act 1952 [Act 366] and Poisons Regulations 1952 [1952 Regulations] and contrary to the Government's public health policy?

Leave Question 6

With the use and effect of the unregistered Ivermectin drugs still pending further clinical research at the World Health Organisation (WHO) with no assurance that Ivermectin could be used on humans or to cure COVID-19, is it defying the interest of justice to legitimise the use of Ivermectin on human and dispensation of Ivermectin by registered medical profession under the Poisons Act 1952 [Act 366] and the Poisons Regulations 1952?".

[3] The largely undisputed background facts and circumstances which gave rise to this appeal are as follows.

Background

Search and Seizure of Ivermectin

[4] On 14 June 2021, an investigating officer from the Selangor Pharmaceutical Services Division entered the 2nd respondent's clinic and purchased from an assistant in that clinic a box of Ivermectin Verpin-12 tablets ('Search and Seizure').

[5] As soon as the sale was completed, officers from the same department entered and confiscated from the 2nd respondent's clinic tablets and capsules, which are said to be Ivermectin medicines ('Ivermectin').

[6] The items that were seized were chemically analysed, and the Jabatan Kimia Malaysia confirmed, in a report dated 3 December 2021, that the items were indeed Ivermectin. The investigation was said to be done under Act 366 and the 1984 Regulations.

The Originating Summons

[7] Dissatisfied with the Search and Seizure, the two respondents jointly filed the Originating Summons dated 21 September 2021 ('OS'), which OS gives rise to the present appeal.

[8] The 1st respondent/plaintiff is a qualified and registered medical practitioner and was at all material times a specialist consultant doctor at Mahkota Medical Centre Sdn Bhd, at No 3, Mahkota Melaka, Jalan Merdeka, 75000 Melaka. He sues on behalf of himself and in the capacity of the Malaysian Association of Advancement of Functional and Interdisciplinary Medicine ('MAAFIM') for which he was, at the time, the President. MAAFIM is itself a lawful society registered under the Societies Act 1969.

[9] The 2nd respondent is also a qualified and registered medical practitioner and operates a clinic under the name and style of Klinik Medik at 9156 Jalan Bandar 4, Taman Melawati, 53100 Kuala Lumpur. He is directly affected by actions that are in question in this case as it was his issued Ivermectin medications that were the subject of the Search and Seizure.

[10] The reliefs sought in the OS are these (in the National Language):

"SAMAN PEMULA

(a) Pentafsiran peruntukan-peruntukan:

i. Akta Racun 1952 termasuk s 2, 12(1)(c), 18(1)(c), 19 dan 21(1) dan (2); dan

ii. Peraturan-peraturan Racun 1952 termasuk Jadual Pertama Bahagian 1 Kategori B.

(b) Satu Penentuan sama ada seorang pengamal perubatan adalah berhak untuk mendispens (dispense) Ivermectin sebagai suatu bahan ramuan kepada pesakit-pesakitnya di bawah Akta Racun 1952 dibaca Bersama dengan Peraturan-peraturan Racun 1952.

(c) Satu Penentuan sama ada seorang pengamal perubatan boleh mendispens Ivermectin kepada pesakit-pesakitnya bagi tujuan rawatan perubatan pesakit tersebut sahaja dan selaras dengan s 19 Akta Racun 1952 Peraturan-peraturan Racun 1952.

(d) Kos; dan

(e) Lain-lain relif yang mana Mahkamah Yang Mulia ini anggap sesuai, wajar dan adil, inter alia, bidang kuasa sedia ada Mahkamah yang Mulia ini.".

[11] The English translation of the said reliefs is substantially the same, but it indicates an additional prayer (d) not found in its National Language counterpart. For the avoidance of doubt, the English translation is reproduced thus:

"SAMAN PEMULA

(a) The interpretation of the provisions of:

i. the Poisons Act 1952 including ss 2, 12(1)(c), 18(1)(c), 19 dan 21(1) and (2) ; and

ii. the Poisons Regulations 1952 including the First Schedule Part I Category B.

(b) A determination whether a registered medical practitioner is entitled to dispense Ivermectin as an ingredient to his or her patient under the Poisons Act 1952 read together with the Poisons Regulations 1952.

(c) A determination whether registered medical practitioner can dispense Ivermectin to his or her patients for the purposes of the medical treatment of such patient only and in compliance with s 19 of the Poisons Act 1952 and the Poisons Regulations 1952.

(d) Declarations, as appropriate, ensuing from the determinations and interpretation as aforesaid.

(e) Costs; and

(f) Such further or other relief which this Honourable Court deems fit, appropriate and just to order under, inter alia, the inherent jurisdiction of this Honourable Court".

[Emphasis Added]

[12] The difference between the two versions is that the English version contains an additional prayer (d), which we shall call the 'Impugned Prayer (d)'. This was a contention by the parties in the High Court, and we shall refer to it where necessary later.

[13] Both parties accept that no criminal proceedings had been instituted against the 1st respondent as at the date of the filing of the OS. However, the appellants confirm that after the OS was filed, a criminal charge was preferred against the 2nd respondent.

[14] There is also no dispute that both respondents were at all material times registered medical practitioners within the meaning of s 2 Act 366 and the Medical Act 1971, especially at the time the 2nd respondent sold the Ivermectin to the investigating officer.

The Present Case

[15] For the avoidance of doubt, reference to Ivermectin will be made throughout this judgment, as has been in the judgments of the lower Courts, as a 'poison'. It does not mean that Ivermectin or any other drug classified as a 'poison' in Act 366 is necessarily a poison in the ordinary understanding of the word poison, such as perhaps rat poison is considered.

[16] Here, 'poison' is a legal term defined in s 2 Act 366 as meaning:

"any substance specified by name in the first column of the Poisons List and includes any preparation, solution, compound, mixture or natural substance containing such substance, other than an exempted preparation or an article or preparation included for the time being in the Second Schedule;".

[17] Anything so included in Act 366 is, therefore a substance regulated by law and should be understood as a 'poison' in that sense.

[18] In general terms, the respondents' case is that under Act 366, it has long been the undisputed right of registered medical practitioners to dispense Group B poisons. The main thrust of the OS, therefore, seeks definitive judicial interpretation of these provisions as against the provisions of Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations − which are the provisions on which the appellants rely. To add context to the thrust of their claim on interpretation, it is their case that the 2nd respondent was entitled to dispense Ivermectin to his patients under the relevant provisions of Act 366 and its 1952 Regulations.

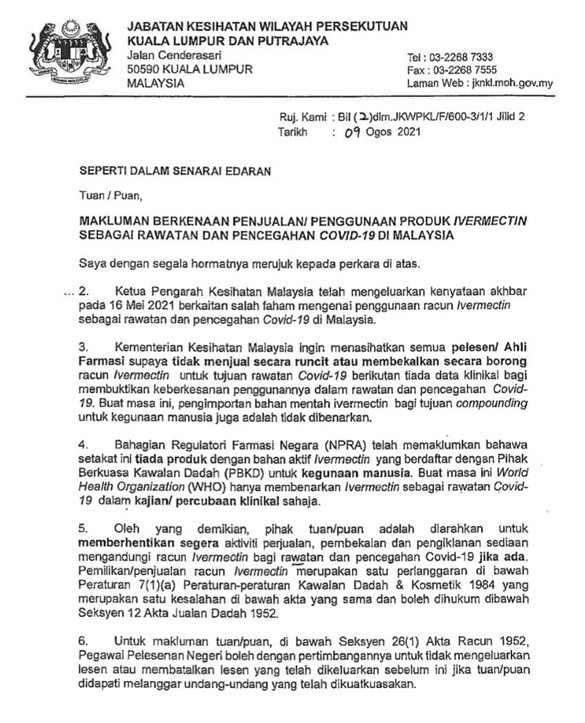

[19] In their submissions, the respondents also suggest that the facts that give rise to the present OS originate from a circular issued by the Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya Health Department ('JKWP') dated 9 August 2021 ('Circular'), as follows:

[20] Vide the above Circular, which was never addressed to the doctors but to pharmacies and pharmaceutical companies, the appellants did, through JKWP, state the following:

(i) The 1st appellant advised all registered/member pharmacies against selling by retail or supplying wholesale Ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 as there is no clinical data to prove its effects in treating or preventing COVID-19. For the material time, the import of raw materials of Ivermectin for the purpose of compounding for human consumption was also disallowed;

(ii) The National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA) has informed that as at the material time, there is no product with Ivermectin as the active ingredient that has been registered with the Drug Control Authority (PBKD) for human consumption. At the material time, the World Health Organisation (WHO) allowed the use of Ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19 in clinical/research trials only.

(iii) As such, the Circular advises all addressees to immediately cease all activities relating to the sale, supply and marketing of the poison Ivermectin as treatment or prevention of COVID-19, if any such activities were carried out.

(iv) The Circular goes on to advise that the possession and/or sale of Ivermectin amounts to a violation of reg 7(1)(a) of the 1984 Regulations and which provision renders the same an offence punishable under s 12 of Act 368.

(v) The Circular concludes that under s 26(1) of Act 366, the State Licensing Officer may in his discretion refuse to issue or cancel any previously issued license if any of the Circular's addressees are found to violate any of the laws in force.

[21] We come now to the relevant provisions. The primary provisions upon which the respondents rely are ss 17, 19 and 21(1) of Act 366, which they submit collectively taken together allow registered medical practitioners (such as the respondents) the right to dispense Group B poisons.

[22] Section 17 of Act 366 reads:

"17. Prohibition of sale to persons under 18

(1) No poison shall be sold or supplied to any person under eighteen years of age, otherwise than for purposes of the medical or dental treatment of such person.

(2) Any person contravening this section shall be guilty of an offence against this Act.

(3) It shall be a sufficient defence to any charge under this section that the person charged had reasonable cause to believe that the person to whom such sale was made was above the age of eighteen years.".

[23] Section 19 of Act 366 provides:

"19. Supply of poisons for the purpose of treatment by professional men

(1) Any poison other than a Group A Poison may be sold, supplied or administered by the following persons for the following purposes:

(a) a registered medical practitioner may sell, supply or administer such poison to his patient for the purposes of the medical treatment of such patient only;

(b) a registered dentist Division I may sell, supply or administer such poison to his patient for the purposes of the dental treatment of such patient only; and

(c) a registered veterinary surgeon may sell or supply such poison to his client for the purposes of animal treatment only.

(2) A registered dentist Division II may sell, supply or administer to his patient for the purposes of the dental treatment of such patient only any poison other than a Group A or a Group B Poison.

(3) Every medicine containing any poison sold or supplied under subsection (1) or (2) shall be prepared by or under the immediate personal supervision of such registered medical practitioner, registered dentist or registered veterinary surgeon, as the case may be:

Provided that any medicine, received by such registered medical practitioner, registered dentist or registered veterinary surgeon in a prepared state from a manufacturer or wholesaler, shall be deemed, for the purposes of this section, to have been prepared by such registered medical practitioner, registered dentist or registered veterinary surgeon respectively, if the receptacle containing such medicine is labelled by or under the immediate personal supervision of such registered medical practitioner, registered dentist or registered veterinary surgeon in such manner as may be prescribed by regulations made under this Act, relating to the labelling of dispensed medicines.

(4) Any registered medical practitioner, registered dentist or registered veterinary surgeon who sells or supplies any poison or medicine containing a poison not prepared by him or under his immediate personal supervision shall be guilty of an offence against this Act.".

[24] Section 21(1) of Act 366, which directly regulates Group B poisons, then goes on to stipulate as follows:

"21. Group B Poisons

(1) Group B Poison shall not be sold or supplied by retail to any person except:

(a) where the sale or supply of such poison, if it had been a Group A Poison, would have been authorized under s 20;

(b) by a registered medical practitioner, registered dentist Division I or registered veterinary surgeon selling or supplying the same in accordance with s 19; or

(c) by a registered pharmacist, as a dispensed medicine on and in accordance with a prescription prescribed by a registered medical practitioner, registered dentist or registered veterinary surgeon in the form required by subsection (2) or (2A) and when supplied in accordance with this Act and of any regulations made thereunder relating to such sale or supply on a prescription".

[25] In summary, the respondents' position is that Ivermectin is included in Group B of Part 1 of the Poisons List in Act 366. In their submission, a cumulative reading of ss 15, 18, 19 and 21 of Act 366 suggests that medical practitioners such as the respondents are expressly permitted to sell wholesale and retail Group B poisons for the use of their patients.

[26] This leads us to the appellants' case.

[27] The appellants' first contention is that by initiating this OS, the respondents have, in effect, sought to stymie or interfere with the criminal process. The OS is effectively an invitation to the civil courts to make findings that ought to be made by the criminal courts on account of the fact that the 2nd respondent has since been charged with an offence upon the Search and Seizure.

[28] Second, on the merits, the appellants accept that the sale of Ivermectin (either by retail or wholesale) and its dispensation is governed by Act 366 and the 1952 Regulations. However, in their submission, such a right should be construed together with the provisions of Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations. Upon the wholesome construction of these provisions, it is the appellants' case that the 2nd respondent was not legally entitled to sell or dispense Ivermectin in the manner he says he is allowed to.

[29] In support of this point, the appellants rely on s 2 of Act 368, in particular, the following terms which have been defined thus:

"In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires:

"drug" includes any substance, product or article intended to be used or capable, or purported or claimed to be capable, of being used on humans or any animal, whether internally or externally, for a medicinal purpose;

"medicinal purpose" means any of the following purposes:

(a) alleviating, treating, curing or preventing a disease or a pathological condition or symptoms of a disease;

(b) diagnosing a disease or ascertaining the existence, degree or extent of a physiological or pathological condition;

(c) contraception;

(d) inducing anaesthesia;

(e) maintaining, modifying, preventing, restoring, or interfering with, the normal operation of a physiological function;

(f) controlling body weight;

(g) general maintenance or promotion of health or wellbeing;

"sale" or "sell" includes barter and exchange and also includes offering or attempting to sell or causing or allowing to be sold or exposing for sale or receiving or sending or delivering for sale or having in possession for sale or having in possession any drug knowing that the same is likely to be sold or offered or exposed for sale".

[30] The appellants urge that s 2 above must be read in conjunction with rr 7(1) and 15(1) of the 1984 Regulations, which respectively stipulate that:

"Regulation 7

7. Prohibition against manufacture, sale, supply, importation, possession and administration.

(1) Except as otherwise provided in these Regulations, no person shall manufacture, sell, supply, import or possess or administer any product unless:

(a) the product is a registered product; and

(b) the person holds the appropriate licence required and issued under these Regulations.

Regulation 15

15. Exemptions and savings

(1) ...

(2) The requirement of reg 7(1) as regards a licence to supply or manufacture does not apply to the dispensing, of any drug for the purpose of it being used for medical treatment of a particular patient or animal, by the following persons and in the following circumstances:

(a) a pharmacist or a person working under the immediate personal supervision of a pharmacist in a retail pharmacy;

(b) a person acting in the course of his duties who is employed in a hospital or dispensary maintained by the Federal or any State Government or out of public funds or by a charity approved for the purposes of s 9(1)(b) of the Poisons Ordinance 1952 or in an estate hospital and who is authorised in writing as provided in that section; and

(c) a fully registered medical practitioner or a dental practitioner or a veterinary practitioner or a person working under the immediate personal supervision of such a practitioner if the drug in question is for the use of such practitioner or of his patients".

[31] It is the appellants' submission that as Ivermectin is a "drug" per the definition in Act 368 then by virtue of the 1984 Regulations, its sale, supply, importation, possession and administration must meet the cumulative requirements of reg 7(1) of the 1984 Regulations namely that it must be a "registered product" and that the 2nd respondent must hold the appropriate licence required and issued under the 1984 Regulations.

[32] The appellants' primary contention is that the 2nd respondent cannot rely solely on the provisions of Act 366 and the 1952 Regulations as he and every other registered medical practitioner are subject to the provisions of Act 368 and its 1984 Regulations.

[33] The appellants further argue that upon fully construing the applicable provisions and concluding that the 2nd respondent cannot sell, dispense or administer Ivermectin, the OS will be seen as an attempt by the respondents to effectively advocate the use of Ivermectin as a suitable treatment for or preventive measure against COVID-19. This, the appellants submit, is a question of executive and/or legislative policy, and any attempt by the respondents to debate the merits of Ivermectin through the Courts amounts to an invitation to judicial overreach on questions of policy.

Decision/Analysis

The Main Issue And Other Preliminary Matters

[34] We have, in essence, framed above the core arguments of parties in support and opposition to the basic propositions raised in this case. In the following parts of the judgment, we will address all remaining submissions and the decisions of the Courts below as we come to decide them.

[35] As we understand it from the facts and circumstances, the primary poser that falls for consideration in this case is ('Main Issue'):

"Can a registered medical practitioner sell (either by retail or wholesale) and/ or dispense for purposes of consumption/administration by their human patients the substance Ivermectin (in whatever form) which is not a 'registered product' and without the benefit of a license for that purpose under the scheme enacted in Act 366 and Act 368 and their respective 1952 and 1984 Regulations?".

[36] The facts in this OS also give rise to two additional issues. From what was summarised earlier, the first issue concerns the legal tenability of the nature of the declarations sought in this case and whether they can, therefore, be granted in light of the doctrine of separation of powers.

[37] The second issue that arises from the submission of the appellants also concerns the doctrine of separation of powers, and it is whether the declarations, if granted, would be tantamount to judicial interference with the executive and legislative policy by effectively accepting Ivermectin as a suitable treatment option or preventive measure for COVID-19.

The Legal Tenability Of The Declaratory Reliefs Sought

[38] Earlier, we reproduced the prayers sought in the OS in both their linguistic versions. However, we do not think it is necessary to venture into the dispute and which of the two versions (Malay and English versions) are authoritative.

[39] The reason for this is because the Court of Appeal only granted an order in terms of prayers (b) and (c) of the OS, which are the same in both versions. The respondents only resist the appeal against the decision of the Court of Appeal and have not filed a cross-appeal to urge this Court to grant prayers not considered, and so they seem content with what the Court of Appeal has decided in their favour.

[40] For the avoidance of doubt, the Court of Appeal granted the following declaratory orders by answering the following two questions in the affirmative in para [84] of its judgment as follows ('Declarations'):

"(a) Satu Penentuan sama ada seorang pengamal perubatan adalah berhak untuk mendispens (dispense) Ivermectin sebagai suatu bahan ramuan kepada pesakit-pesakitnya di bawah Akta Racun 1952 dibaca Bersama dengan Peraturan-Peraturan Racun 1952;

(b) Satu Penentuan sama ada seorang pengamal perubatan boleh mendispens Ivermectin kepada pesakit-pesakitnya bagi tujuan rawatan perubatan pesakit tersebut sahaja dan selaras dengan s 19 Akta Racun 1952 Peraturan-Peraturan Racun 1952".

[41] Henceforth, any references to Declarations refer to the above two declarations, which were granted by the Court of Appeal in favour of the respondents.

[42] From the High Court right up until the arguments before us, learned Senior Federal Counsel (SFC) for the appellants maintained that the declarations in the nature sought exceed judicial power. Their submission is best captured in their own words, as follows:

"2.4 In the light of the criminal investigation, the OS raised serious questions as to the jurisdiction of the Court. The Civil Court has no jurisdiction to determine questions of criminality and does not interfere with ongoing criminal investigation.

2.5 The purpose and effect of the Respondents' claim / OS is to pre-empt, impede and interfere with the ongoing criminal investigation against the 2nd Respondent by asking the Civil Court to determine the criminality ie the dispensation of Ivermectin by medical practitioners to their patients for the treatment of COVID-19 is not a criminal offence."

[43] In support of this argument, the appellants place reliance on numerous judgments foremost of which include: Government of Malaysia v. Lim Kit Siang & Another Case [1988] 1 MLRA 178 ('Lim Kit Siang'); Lai Soon Onn v. Chew Fei Meng & Other Appeals [2018] 6 MLRA 633 ('Lai Soon Onn'); Tengku Jaffar Tengku Ahmad v. Karpal Singh [1993] 2 MLRH 558 ('Tengku Jaffar'); and Empayar Canggih Sdn Bhd v. Ketua Pengarah Bahagian Penguatkuasa Kementerian Perdagangan Dalam Negeri Dan Hal Ehwal Pengguna Malaysia & Anor [2015] 1 MLRA 341 ('Empayar Canggih').

[44] It is their submission that these judgments support the proposition that a declaration cannot be granted, much less be entertained, if the effect of the declaration is such that it impedes upon a criminal proceeding or enforces a matter which is rightly within the jurisdiction of the criminal courts.

[45] It is our view that the appellants are entirely correct on the law with respect to the nature and limitations of declaratory judgments. There are sound reasons grounded on policy as to why declarations cannot impede upon the criminal courts.

[46] Firstly, the power to institute, conduct and discontinue criminal proceedings is exclusively for the Public Prosecutor by virtue of art 145(1) of the Federal Constitution. No private person has such a right. In other words, no private party may attempt to sue another private person for a declaration that seeks to condemn that other party for having committed an offence.

[47] Secondly, and as a natural consequence to the first, criminal proceedings are governed by entirely different considerations including a much higher standard of proof, ie beyond a reasonable doubt. Civil proceedings, on the other hand, are decided on a balance of probabilities, and to allow them to be used as a basis to find criminal liability would be in total violation of all principles known to criminal law, including the right of a fair trial and the presumption of innocence.

[48] The cases cited by the appellants support these theories. In Lim Kit Siang, the respondent had sought (among other things) declarations to the effect that the then Prime Minister and two other Government Ministers had engaged in corrupt practices. The Supreme Court held that such declarations were impermissible because they ought to be determined by the criminal courts and not the civil courts. Taking such a course was, in the words of Salleh Abas LP (at p 193), likened to a prosecution done behind the Attorney-General cum Public Prosecutor's back.

[49] In Lai Soon Onn, the plaintiffs had, among other things, sought declarations to the effect that the defendants had committed a criminal offence under the Capital Markets and Services Act 2007. In this regard, the Court of Appeal observed:

"[39] By the very nature of the declaratory reliefs prayed for, essentially the plaintiff seeks a declaration that the defendants committed a criminal offence under the CMSA. Before such a declaration can be made there must be a determination of a contravention. By filing his claim in the civil courts the plaintiff is seeking for such determination to be made by the civil court in a civil proceeding. Such cannot be the case. The burden of proof between the two is different. Essentially, it is not for the civil courts to intrude into the domain of the criminal court. That cannot be the intention of s 357 of theCMSA".

[50] Reference was also made to Lim Kit Siang to arrive at the same conclusion that declarations cannot be used in this way.

[51] The same is the case cited by the appellants in Tengku Jaffar, where Idris Yusoff J held in respect of the plaintiff's prayer for a declaration that the defendant's statement amounted to seditious libel, at p 563 as follows:

"In the circumstances, I agree with Mr Karpal Singh that the issues which relate to the alleged criminality do not come within the purview of a civil court as otherwise, the civil court might be accused of intruding into the domain of the criminal court. In the instant case, it is clear that the plaintiff has made a complaint to the wrong forum".

[52] The next authority cited by the appellants that warrants discussion is Empayar Canggih. The facts were briefly these.

[53] The appellants were suspected of having committed offences under the Optical Discs Act 2000 ('ODA 2000'), and certain investigating officers from the Ministry of Trade and Consumer Affairs, acting on information received, seized machinery and equipment belonging to the appellants. The appellants then filed a judicial review application seeking writs of mandamus and certiorari against the Government, alleging that such search and seizure was unlawful. By the time the judicial review came to be heard, the seized items had been returned, and the appellants amended their claim to only include primarily declarations that such search and seizure was unlawful and damages on account of the same.

[54] The High Court dismissed the judicial review application principally on the grounds that the appellants' challenge ought to have been initiated by way of a writ and not judicial review. This was upheld on appeal to the Court of Appeal. The sole question before the Federal Court was whether such a claim could have been commenced by way of judicial review.

[55] One of the many arguments raised before the Federal Court by the Government in Empayar Canggih was that their seizure of the machinery and equipment was lawful and permitted under the ODA 2000 in connection with investigations into the suspected commission of an offence under that Act. The Government's exercise of this statutory function was part of the investigation process of a law enforcement agency and, as such, was not an administrative decision that was amenable to judicial review.

[56] The present appellants rely on this judgment for their point that criminal investigations cannot be impeded upon, as indeed, this is what this Court held in Empayar Canggih:

"[25] Similarly in the present appeal, the seizure was made in the course of a criminal investigation of an offence under Act 606 pursuant to the powers conferred under the Act. Such seizure clearly is not amenable to judicial review. The appellant was not without redress. It could have filed a private law writ action for damages. Indeed, s 48 of Act 606 provides for a cause of action for recovery of damages if a seizure is made without reasonable cause.

[26] Our answer to the first leave question as modified by us therefore is that, a challenge to the exercise or a purported exercise of the power to seize the machinery and equipment in this case should be made by way of an ordinary private law action for damages".

[57] With the greatest of respect to the appellants, this authority is of no assistance to them. It is an accepted point of law that criminal investigations ought not to be impeded by abusing the law and legal process, but other than that, Empayar Canggih only decided on the point that such an action could not proceed by way of judicial review. The decision affirms that criminal investigations can be challenged in an action for damages. Yet, whatever the reasoning, the present appeal/OS is not grounded on a judicial review application but for declarations on certain rights, the respondents say they and other registered medical practitioners have under the law.

[58] The appellants raised these very arguments in the High Court, and the said Court accepted them based on most of the authorities cited above. The learned Judge found that the declarations sought by the respondents did impede upon or interfere with any possible criminal investigations that may be brought against the 2nd respondent. The learned Judge went on to conclude that the OS was an abuse of process and was frivolous.

[59] The Court of Appeal however held that the learned Judge erred in his assessment of the case; that the OS was not brought with a collateral purpose of interfering with the criminal investigations brought against him; and that the High Court had failed to appreciate the judgment of the former Federal Court in Datuk Syed Kechik Syed Mohamed v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [1978] 1 MLRA 504 ('Syed Kechik') which case is also addressed before us in Leave Question 1.

[60] The Court of Appeal accepted the respondents' contention that Syed Kechik is the authority for the proposition that a declaration of rights of a party can be requested from the Courts before the event that the party is trying to avoid occurs.

[61] Before us, the respondents' principal submission also rests on the judgment in Syed Kechik and additionally a judgment of this Court in YAB Dato' Dr Zambry Abd Kadir & Ors v. YB Sivakumar Varatharaju Naidu; Attorney-General Malaysia (Intervener) [2009] 1 MLRA 474 ('Zambry').

[62] The facts of Syed Kechik were these. The appellant in that case deposed cogent reasons to believe that the Government of Sabah was attempting to deprive him of his status as a native of Sabah, which was previously declared in his favour by the Native Court. He had also been permanently residing in Sabah and had built his life there. He, therefore filed a suit seeking declarations to the effect that he be declared an Anak Negeri of Sabah, that he has a valid permanent residence status and that any Entry Permit previously issued in his favour cannot be revoked.

[63] Against these prayers for such declaratory reliefs, the Federal Government which was party to the case argued that no such action had been taken to deprive the appellant of such rights (as alleged) and indeed the Court below similarly found the matter to be premature and that the matter ought more properly to be dealt with under the special machinery of the Immigration Acts.

[64] This Court unanimously found in favour of the appellant and held that he was entitled to the declaratory reliefs sought. His action was not premature, but more pre-emptive. In this regard, the following dictum of Suffian LP is instructive, at p 507:

"In my view, the applicant has a real fear that he may be expelled from Sabah, and it is desirable for the court to declare whether or not the Federal and State Governments have a right to expel the applicant, so that all parties concerned will know exactly where they stand.".

[Emphasis Added]

[65] In the same case, Lee Hun Hoe CJ Borneo observed thus, at p 517:

"It is the submission of appellant that he has no other remedy of establishing his right to reside in Sabah. The declaration sought is not as to his future right but as to his present right. There has been a threat to his right by official statement of the party in power. The threat has never been denied or withdrawn. A political party can only realise its objectives if it were in power. He need not have to wait for something to happen before seeking the court's protection... A declaratory order will eliminate anxiety of having to live under a cloud of fear. In granting a declaration, the court has to consider the utility of the declaration claimed and the usefulness of the declaration on the one hand as against the inconvenience and embarrassment that may result on the other hand. As to the determination of future right its importance for certain purposes is not in doubt, particularly when a mere declaration is usually the only remedy."

[Emphasis Added]

[66] What is clear from the above dicta, which we consider form the ratio decidendi of Syed Kechik is that the very utility of declaratory orders is to inform parties concerned "exactly where they stand" and that the affected party "need not have to wait for something to happen before seeking the court's protection". These pronouncements are entirely consistent with our locus classicus on declarations and declaratory reliefs in Tan Sri Haji Othman Saat v. Mohamed Ismail [1982] 1 MLRA 496 ('Othman Saat") wherein the same former Federal Court, at p 498, reaffirmed the point that declarations may 'generate rights'.

[67] The exact same principle was considered and applied by this Court in Zambry. In that case, the appellants were assemblymen of the Perak State Legislative Assembly who initiated the action for declaratory relief that their suspension from the State Assembly was null and void during the pendency of disciplinary proceedings against them. The argument opposing the action was that the appellants could not seek such declarations because it was designed to frustrate the disciplinary proceedings against them. It was held that the appellants were entitled to seek such declarations of their legal rights. See: Zambry, at [30]-[32].

[68] In the instant case, the Court of Appeal held (at [81]) that the decisions of Syed Kechik and Zambry applied to the present respondents, mainly the 2nd respondent, because he is seeking declarations on his position and rights under Act 366.

[69] It has been the respondents' principal stance from day one that they are only subject to Act 366 and the 1952 Regulations in their dispensation of Ivermectin for the treatment of their patients only. They claim that they are not subject to Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations in this regard. As such, it is their submission that the declarations are not designed to impede or interfere with criminal investigations against the 2nd respondent, but rather, it is for them and all registered medical practitioners to know their rights and position under the law.

[70] On the authorities cited above and for the reasons that follow, we accept the respondents' argument and the decision of the Court of Appeal as entirely correct on the facts. As such, we find that the High Court was erroneous in holding that the respondents were attempting to interfere with the criminal investigations to the extent of the relief prayed for in the Declarations. We must stress again here that by 'Declarations' we are referring only to the relief granted by the Court of Appeal.

[71] The respondents have not at all challenged the legality of the Search and Seizure, nor have they suggested or asked for any relief to the effect that the 2nd respondent ought not to be prosecuted or that he had not committed any offence. In respect of the 1st respondent, their learned counsel submits that they too, representing a body of qualified specialists and doctors have the right to determine the extent of the legal rights of all doctors to dispense Group B poisons and the extent of how such a right is limited, if at all, by Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations.

[72] The nature of the relief sought in this case is purely and entirely to move the Court to exercise its most basic functions of judicial interpretation to determine the state of the law as regards Acts 366 and 368 and their respective Regulations (1952 and 1984).

[73] The law is settled beyond any dispute that it is only the Courts that may make determinative findings of factual and legal rights. While it remains the Public Prosecutor's sole right to charge any person for an offence, such a power is exercised in accordance with written law. Where the law is unclear, it is only the Courts who may finally determine the interpretation of that law or rule. Such a final determination would then also serve the effect of putting parties on notice on "exactly where they stand" in terms of their present and future rights — as determined in Syed Kechik.

[74] In line with the above authorities, we think the situation as regards declarations can be explained through the following analogy. Let us assume that a person named X rides into a public park on his bicycle where there is a sign that says 'it is an offence to bring or ride any vehicle into this park' and there is no definition of 'vehicle' in any law. With this, we can now posit the following five hypothetical scenarios.

[75] In the first hypothetical scenario, X has been threatened with an action against him for riding in the park with his bicycle or in the absence of such a threat, X just wants clarity or comfort on whether he was in violation of the rule. As such, X initiates an action for a declaration that his bicycle is not a vehicle within the meaning of the words employed in the park sign. X therefore seeks a declaration to ascertain his legal rights and to know "exactly where he stands". By the foregoing authorities, he can do this, and the suit cannot be said to be frivolous or an abuse of process.

[76] In the second hypothetical scenario, it is not X but another private person who frequents the same park and who is of the opinion that 'vehicle' includes bicycles, who files a suit for a declaration that 'vehicle' includes 'bicycles'. This private person either does this to seek clarity on X's actions or because he wants to know what the law is. This, by virtue of the foregoing authorities cited, is permissible.

[77] In the third scenario, the same private person, offended by X's actions, decides to take matters into his own hands. Instead of seeking a determination of the meaning of 'vehicle' and whether it includes 'bicycle' files a suit against X to declare that X has committed an offence by riding his bicycle in the park. For the reasons earlier explained, this is impermissible, and such a declaration cannot, therefore, be granted or much less, be entertained.

[78] In the fourth scenario, the Public Prosecutor decides to charge X with an offence of violating the rule in the public park sign. X's guilt cannot be determined by the civil standards applicable in an application for a criminal trial, and as such, the only way he can be made to answer for his offence is by way of the Public Prosecutor, in his discretion, preferring a charge against him. Whether or not 'vehicle' includes 'bicycle' can and will be decided as a question of law in that trial as that would be the first judicial determination that must be made. Thereafter, any further judicial determination can be made on the evidence on whether X did, in fact, commit the offence beyond a reasonable doubt.

[79] In the fifth and final scenario, X is prosecuted for the offence in the manner described in the fourth scenario above. But, whether during the investigation stages or during the pendency of the charge, X is entitled to file a civil action for a declaration to the effect that 'vehicle' in the sign does not include 'bicycle'. While the prosecution might take the position that 'vehicle' means 'bicycle' in the criminal proceedings, that question of interpretation of the law can be decided by the civil courts at any stage, and X is entitled to have that question decided as a means to gauge "exactly where he stands".

[80] It would be appreciated at once that the fifth scenario (considered in light of all the other four scenarios) illustrates how there is a clear and distinct demarcation of powers between the prosecutor-executive and the judicial branch that is alone constitutionally empowered and tasked to interpret the law.

[81] In scenarios four and five above, it is clear that X may do one of two things. One, he may either raise the defence in the criminal proceedings that 'vehicle' cannot and does not include 'bicycle' in addition to presenting evidence exculpating him from any allegations that he did ride his bicycle in the park in offence to the sign. Yet, there is also his opportunity to clarify the state of the legal interpretation of the word 'vehicle' in separate civil proceedings for a declaration to the effect that such a word cannot include 'bicycle'.

[82] This is entirely consistent with our system of criminal law in that the accused must always be presumed innocent until proven guilty and that the right to a fair trial must be preserved. This equation also factors into account the crucial detail that the accused must be given every opportunity to present his defence and to know the case that is made against him. This includes the right to know "exactly where he stands" in relation to the law.

[83] Naturally, if a judicial determination is made in the civil proceedings that 'vehicle' does not include 'bicycle', then any criminal case sought to be made against X would have no legal leg to stand on. But, that cannot by any measure be taken to mean that X is impeding upon or interfering with criminal proceedings that have or might be brought against him. If the determination is such that it is declared against X that 'vehicle' does include 'bicycle' in the context of that sign in the park, then X would know that such a defence is not available to him and he can elect either to plead guilty to the offence or plead not guilty and claim trial to attempt to exculpate himself of any charge preferred or any evidence adduced against him.

[84] In this entire assessment and prior to the making of any such determination of the meaning of the word 'vehicle', there is virtually nothing that potentially affects the criminal investigations. While the criminal court may be minded to stay the criminal proceedings pending the civil suit, there is nothing prohibiting the prosecution from pursuing investigations against X, questioning eye-witnesses or taking any statements that can help support an eventual prosecution.

[85] If the declaration is made against X's favour, the prosecution can then stand firm on its resolve to prosecute X, and X, in turn, will (as stated earlier) have notice that the defence that the interpretation of 'vehicle' does not include 'bicycle' is no longer available.

[86] We indicated earlier that the appellants' submission on the law and their interpretation of the cases they have cited, such as Lim Kit Siang, as well as the limits of declaratory judgments, is correct. However, we find that the appellants' application of such law and principles to the facts of this case is entirely misplaced.

[87] For the reasons that have been stated in our analysis above, while Syed Kechik and Zambry do not on their facts concern the grant of declarations pending criminal charges or investigations, we hereby hold that their collective ratio decidendi extends to and applies mutatis mutandis to a case, such as this one, where the person(s) so affected seek(s) to the extent clarify or determine his or their legal rights or position.

[88] We accept the respondents' submission that the Declarations do not impede upon or interfere with any criminal investigations and that the declarations will assist them in clarifying their legal rights vis-à-vis Acts 366 and 368 and their attendant Regulations. The facts of the present case are therefore akin to the fifth hypothetical scenario earlier elaborated. Further, ss 18, 19 and 21 of Act 366 themselves specifically contain procedures and principles which all registered medical practitioners must follow, and to the extent that the criminal investigations relate to this, they remain open and unimpeded.

[89] We therefore, uphold the decision of the Court of Appeal as correct in reversing the High Court on any finding that such Declarations are an abuse of process or frivolous and/or vexatious.

[90] Consequently, Leave Question 1 is answered in the affirmative.

Statutory Construction

Act 366 And The 1952 Regulations

[91] The next aspect of the case concerns the Main Issue, which is perhaps substantively the most important to the OS. This concerns the statutory construction of Act 366 and Act 368, and their respective Regulations 1952 and 1984.

[92] The preamble to Act 366 clarifies its purpose being thus:

"An Act to regulate the importation, possession, manufacture, compounding, storage, transport, sale and use of poisons".

[93] As was set out earlier, 'poisons' is a specific legal term referred to the Act for purposes of regulation of such items that have been defined in s 2 to mean "any substance specified by name in the first column of the Poisons List and includes any preparation, solution, compound, mixture or natural substance containing such substance, other than an exempted preparation or an article or preparation included for the time being in the Second Schedule".

[94] The pillar of Act 366 is, therefore, the Poisons List, which is contained in the First Schedule.

[95] The Poisons List is, in turn, split into Part I and Part II. Part I is further split into six categories or 'Groups' beginning in the order of Group A until Group F. Ivermectin in 'all preparations' is included and referred to in the Poisons List, First Schedule as a Group B poison.

[96] We will note here that the preamble to Act 366 is comprehensive in that it covers a wide range of activities in relation to 'poisons'. In this regard, the structure of Act 366 contains specific sections that appear to deal with all the categorised purposes of the Act in its preamble.

[97] Correspondingly, s 8 deals with importation; s 13 with possession; s 11 with manufacture; s 12 with compounding; s 9 with storage (and related matters); s 10 with transport; ss 15 to 18 with sale (through various methods).

[98] Specifically, s 15 concerns the sale of poisons by wholesale and s 16 concerns sale by retail. Sections 17 and 18 in turn, relate to certain prohibitions on sale or supply under ss 15 and 16. Before addressing s 19, we specifically observe that the set of provisions in ss 20 until 23 deal respectively with poisons in Group A to Group D.

[99] The following definitions of "sale" and "supply" in s 2 of Act 366 are also important, namely:

"sell" or "sale" includes barter and also includes offering or attempting to sell;

"supply" includes the supply of commercial samples and dispensed medicines, but does not include the direct administration by or under the immediate personal supervision of a registered medical practitioner or registered dentist of a poison or medicine to his patient in the course of treatment where such administration is authorized under s 19".

[100] Section 2 also defines "wholesale" and "retail sale" as follows:

"retail sale" means any sale other than a wholesale sale;

"wholesale" means a sale to any person who intends to sell again and any sale by a licensed wholesaler authorized by paras (d) to (k) inclusive of s 15(2);".

[101] We come then to s 19, which is the principal provision upon which the respondents rely. Specifically, s 19(1)(a) unequivocally stipulates, in part relevant to the present case, that a registered medical practitioner may sell, supply or administer any Group B poison to his patient for the purposes of the medical treatment of such patient only. The operative words in relation to any registered medical practitioner are "sell, supply or administer". For clarity, we reproduce the provision again as follows:

"19. Supply of poisons for the purpose of treatment by professional men

(1) Any poison other than a Group A Poison may be sold, supplied or administered by the following persons for the following purposes:

(a) a registered medical practitioner may sell, supply or administer such poison to his patient for the purposes of the medical treatment of such patient only;...".

[102] And so, to decipher the meaning of the three words "sell, supply or administer", we must have regard to the statutory definitions of Act 366 and the structure of its provisions earlier highlighted.

[103] We have perused the descriptions of "sale by wholesale" and "sale by retail" in ss 15 and 16 (for brevity, we will not reproduce), and s 18(1)(c) of Act 366, which provides thus:

"18. Restriction on the sale or supply of Part I poisons generally

(1) Part I Poison shall not be sold or supplied to any person except:

(a)

(b)

(c) as an ingredient of a dispensed medicine, by a registered medical practitioner, registered dentist or registered veterinary surgeon in accordance with s 19; or...".

[104] We also look at s 21 of Act 366 (which deals specifically with Group B poisons), which stipulates as follows in subsection (1)(b):

"21. Group B poisons

(1) Group B Poison shall not be sold or supplied by retail to any person except:

(a)

(b) by a registered medical practitioner, registered dentist Division I or registered veterinary surgeon selling or supplying the same in accordance with s 19; or.".

[105] From the rather confusing arrangement of the provisions, our analysis points to the conclusion that under s 19(1)(a) of Act 366, registered medical practitioners may issue Group B poisons to any person either by sale or supply (which would involve a financial transaction) or administer (which involves direct administration and personal supervision) all on the condition that such a person is that registered medical practitioner's patient and that such "sale, supply or administration" is for the treatment of that person as a patient.

[106] We are further fortified in this view by reason of the fact that s 21(2) (which section deals with Group B poisons) contains an entire procedure on prescriptions and how such poison (considered medication) is sold or supplied to the patient for the treatment of that patient.

[107] As such, because Ivermectin is classified as a Group B poison in the First Schedule (and it is not therefore a Group A poison), it would follow as per s 19(1)(a) of Act 366 that any registered medical practitioner may sell, supply or administer Ivermectin to his patient for the treatment of his patient only and only by reason of the fact that the person so selling, supplying or administering Ivermectin is a registered medical practitioner.

[108] We therefore agree with the respondents' submission that under s 19 of Act 366, and having regard to the scheme of that Act, the 2nd respondent (as are all other registered medical practitioners) is allowed by law to dispense Ivermectin to his patients provided that such dispensation is for the purposes of that patient's treatment only.

[109] In our view, the 1952 Regulations have little bearing on this interpretation because the rights to dispense (sell or supply) and administer Ivermectin as a Group B poison is substantively determined by Act 366 as the parent or primary legislation to the 1952 Regulations. Further, the 1952 Regulations deal more with technical matters, mainly such as storing, labelling, packaging and import of poisons, and not with the substantive rights of registered medical practitioners that are regulated expressly by ss 19 and 21 of Act 366.

[110] We will now consider the appellants' arguments on the interpretation to be afforded to Act 366 in light of Act 368 and its 1984 Regulations.

Act 368 And The 1984 Regulations

[111] It is the appellants' case that Ivermectin is not registered for human use and is an unregistered drug that cannot, therefore be prescribed to human patients for that purpose. They submit that the decision of the Court of Appeal has the effect of legitimising the use of Ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 notwithstanding that Ivermectin (as an active ingredient) has not been registered with the Drug Control Authority (PBKD), and that if at all Ivermectin has been used for such a purpose, it has only seen such limited use in clinical trials.

[112] It is the appellants' submission that Act 366 cannot be read alone and must be read subject to other laws on the subject, in this case, Act 368 and its 1984 Regulations. It is therefore, their submission that the Court of Appeal failed to pay sufficient consideration to the regime in Act 368.

[113] The crux of the appellants' submission rests on the fact that Ivermectin "can also be categorised as a drug' to the extent that it is used to alleviate, treat, cure or prevent a disease or a pathological condition or symptoms of a disease in humans.

[114] We now consider Act 368.

[115] The preamble of Act 368 defines its purpose as:

"An Act relating to the sale of drugs".

[116] Section 2 of Act 368 defines "drug" as meaning to include:

"any substance, product or article intended to be used or capable, or purported or claimed to be capable, of being used on humans or any animal, whether internally or externally, for a medicinal purpose;".

[117] "Medicinal purpose" is in turn, defined to include:

"any of the following purposes:

(a) alleviating, treating, curing or preventing a disease or a pathological condition or symptoms of a disease;

(b) diagnosing a disease or ascertaining the existence, degree or extent of a physiological or pathological condition;

(c) contraception;

(d) inducing anaesthesia;

(e) maintaining, modifying, preventing, restoring, or interfering with, the normal operation of a physiological function;

(f) controlling body weight;

(g) general maintenance or promotion of health or well-being;".

[118] Section 2 continues with its definitions, ending with the following definition of "sale or sell" where it stipulates that it:

"includes barter and exchange and also includes offering or attempting to sell or causing or allowing to be sold or exposing for sale or receiving or sending or delivering for sale or having in possession for sale or having in possession any drug knowing that the same is likely to be sold or offered or exposed for sale.".

[119] Once a "drug" is determined under Act 368, reg 7 of the 1984 Regulations stipulates in material part in sub-regulation (1) that:

"7. Prohibition against manufacture, sale, supply, importation, possession and administration.

(1) Except as otherwise provided in these Regulations, no person shall manufacture, sell, supply, import or possess or administer product unless:

(a) the product is a registered product; and

(b) the person holds the appropriate licence required and issued under these Regulations".

[120] By reason of the conjunction "and" used in the above provision, the appellants submit that the two requirements are cumulative. Both must be fulfilled before any person can manufacture, sell, supply, import or possess or administer any such product.

[121] The appellants then rightly highlight r 15(2)(c) of the 1984 Regulations that exempts registered medical practitioners from the requirement of having a license, as follows:

"15. Exemptions and savings

(1) ...

(2) The requirement of reg (7(1) as regards a licence to supply or manufacture does not apply to the dispensing, of any drug for the purpose of it being used for medical treatment of a particular patient or animal, by the following persons and in the following circumstances:

(a) ...

(b) ...

(c) a fully registered medical practitioner or a dental practitioner or a veterinary practitioner or a person working under the immediate personal supervision of such a practitioner if the drug in question is for the use of such practitioner or of his patients".

[Emphasis Added]

[122] Accordingly, the appellants submit that the main issue here is that while the 2nd respondent is exempted from the license requirement in r 7(1)(b) by virtue of r 15(2)(c), he and other registered medical practitioners remain bound by the requirement of r 7(1)(a) for which there is no statutory exemption against its requirement that the product must first be a "registered product".

[123] It is not disputed that under Act 368 and the 1984 Regulations, there is no drug with Ivermectin as an ingredient suitable for the consumption of human patients.

[124] In answer to these arguments, the respondents' position is simply that Act 368 does not apply, not only in relation to the 2nd respondent, but to all registered medical practitioners who are only subject to Act 366 in their dispensation of Ivermectin to their patients and for the use of the treatment of those patients only.

[125] In relation to the application of Act 366, while the appellants have minimally conceded that Act 366 "has never catered or dealt with the requirement of the product itself to be registered" they assert that "the so called right vested under Act 366 in relation to sale and supply of Ivermectin is still subject to the provisions of Act 368 and 1984 Regulations."

[126] The respondents therefore stress the point that Act 366 overrides Act 368 insofar as the right to dispense Group B poisons is concerned and that r 7 of the 1984 Regulations, being a subsidiary legislation, cannot supplant or replace primary legislation in Act 366. It is also their submission that Act 368 is a specific law passed only for a certain purpose as opposed to the allencompassing Act 366.

[127] It has also been highlighted to us that both Acts 366 and 368 are statutes of even year. Act 366 was enforced on 1 September 1952, while Act 368 was enforced only two months later on 1 November 1952. They are, in essence, in pari materia.

[128] The Court of Appeal accepted the respondents' submission on the non-applicability of Act 368 to the present facts. In this regard, the Court of Appeal's findings in its written judgment are:

(i) When Parliament enacts laws, especially laws within the same year and for similar purposes, such that these laws form a system or code of legislation, these laws must be construed harmoniously. See: [60]-[63].

(ii) The autonomous rights of registered medical practitioners to dispense Group B poisons (including Ivermectin) is statutorily conferred to them by ss 18, 19 and 21 of Act 366. The only abridgement of this right (in the manner suggested by the appellants) is through rr 7 and 15 of the 1984 Regulations. The Court of Appeal in this respect held that a subsidiary legislation cannot curtail the rights conferred by primary legislation.

[129] For the point in (i) mentioned above, the Court of Appeal also relied on its prior judgment in Tey Por Yee & Anor v. Protasco Bhd & Other Appeals [2020] MLRAU 69 wherein the Court of Appeal cited with approval certain treatises, as follows:

"[99] The meaning of the phrase 'in pari materia' was extensively discussed in Shah & Co v. State of Maharashtra [1967] AIR SC 1877, where Vaidialingam J said, at pp 1882-1883:

(21) We have been referred to certain passages in certain text books, as well as in certain decisions, to show, under what circumstances, statutes can be considered to be in pari materia, and the nature of the construction to be placed on such statutes.

"Sutherland, in 'Statutory Construction', 3rd Ed, Vol 2, at p 535, states: Statutes are considered to be in pari materia-to pertain to the same subject matter- when they relate to the same person or thing, or to the same class of persons or things, or have the same purpose or object"

The learned author, further states, at p 537: