Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

See Mee Chun, Azman Abdullah, Ahmad Kamal Md Shahid JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: W-02(NCVC)(W)-1094-07-2023]

11 December 2024

Contract: Breach — Claim for RM10 million under Bond executed by appellant following appellant's resignation from political party ('party') — Whether events triggering Bond occurred — Whether amount claimed unreasonable and out of proportion to interest of party in enforcing appellant's obligation under the Bond — Whether respondent entitled to reasonable compensation by reason of appellant's breach, and not RM10 million as stipulated in the Bond

The appellant had contested and won the Ampang Parliamentary seat in the 14th General Election ('GE-14') as a Parti Keadilan Rakyat ('party') candidate. The appellant had executed a bond whereby she acknowledged that she was bound to pay the party RM10 million in the event inter alia, she resigned or her membership of the party was terminated. On or about 24 February 2020 the appellant and 10 other Members of Parliament announced their resignation from the party without resigning as Members of Parliament for their respective constituencies. Consequent thereto, a resolution was passed ('resolution') terminating the appellant's membership and the appellant was sued for payment of the sum of RM10 million under the Bond and in the alternative the sum of RM12,049,459.20 under s 71 of the Contracts Act 1950 ('Act'). The appellant denied having consented to or signed the Bond and claimed that the same was invalid and unenforceable against her. The High Court Judge ('HCJ') allowed the respondent's claim and held inter alia that the purpose of the Bond was to instil the importance of loyalty to the party and deter an elected candidate from being disloyal to the party; that the RM10 million was not excessive or punitive and would act as a deterrent for any disloyalty. The High Court essentially found the Bond to be an agreement which fulfilled all the requirements of a valid contract. Hence the instant appeal. The appellant submitted that in order for the Bond to be enforced, the trigger events as stipulated therein had to have occurred and a certificate issued as to whether the appellant had resigned or had her membership terminated; and that the RM10 million was unreasonable, excessive and exorbitant. The respondent however submitted that the RM10 million was reasonable compensation within the meaning of s 75 of the Act.

Held (allowing the appeal in part; amount payable reduced to RM100,000.00):

(1) On the facts, the event triggering the Bond had occurred and the HCJ was correct in finding that there had been a breach of the Bond. (paras 23-24)

(2) Although the party had a legitimate interest in maintaining its political position, the RM10 million was out of proportion to such interest, given that the amount was not confined to a single Parliamentary seat, that the formula of the RM10 million was based on 222 divisions for the party at national level, and the fact that the appellant's 22 months of service as a Member of Parliament was not taken into account. (paras 50-51)

(3) The HCJ had failed to consider whether the RM10 million was reasonable compensation, s 75 of the Act, and to discuss Cubic Electronics Sdn Bhd v. Mars Telecommunications Sdn Bhd and Cavendish Square Holding BV v. El Makdessi & ParkingEye Ltd v. Beavis. On the evidence, the RM10 million could not be construed as reasonable compensation but was instead, unreasonable, extravagant, unconscionable and not in proportion to the legitimate interest sought to be protected. (paras 52-53)

(4) The appellant's admission that the substantial value provided by the party far exceeded the RM10 million stated in the recital to the bond must be considered in light of what constituted reasonable compensation. (paras 54 & 60)

(5) The finding that the RM10 million was not reasonable compensation did not absolve the appellant from any liability. The appellant having breached the Bond, it followed that the respondent was entitled to some reasonable compensation, but not RM10 million. (para 61)

(6) The fact that RM200,000.00 was the maximum amount to be spent in GE-14 for a Parliamentary seat and the appellant's contribution to the party in GE14, were valid factors which went towards proportionality. In the circumstances, RM100,000.00 was a more reasonable compensation and the HCJ was therefore wrong in allowing the claim for RM10 million. (paras 62 & 64)

Case(s) referred to:

Cavendish Square Holding BV v. Talal El Makdessi & ParkingEye Limited v. Beavis [2016] 2 All ER 519 (folld)

Cubic Electronics Sdn Bhd v. Mars Telecommunications Sdn Bhd [2019] 2 MLRA 83(folld)

Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v. New Garage & Motor Co Ltd [1915] AC 79 (refd)

Greer And Another v. Kettle [1938] AC 156 (refd)

Hadley v. Baxendale [1854] 9 Exch 341 (refd)

Johor Coastal Development Sdn Bhd v. Constrajaya Sdn Bhd [2009] 1 MLRA 654 (refd)

Luggage Distributors (M) Sdn Bhd v. Tan Hor Teng & Anor [1995] 1 MLRA 496 (refd)

Selva Kumar Murugiah v. Thiagarajah Retnasamy [1995] 1 MLRA 188 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Contracts Act 1950, ss 2, 71, 75

Evidence Act 1950, s 23

Others referred to:

Chitty on Contracts, 33rd Edn, p 1930, para 26-211, p 1933, para 26-214

Sir Kim Lewison, The Interpretation of Contracts, 6th Edn, p 560

Counsel:

For the appellant: Azhar Azizan @ Harun (Muhammad Firdaus Shaik Alauddin & Muhammad Nizamuddin Abdul Hamid with him); M/s Zharif Nizamuddin

For the respondent: Ranjit Singh (William Leong Jee Keen & Navpreet Singh with him); M/s William Leong & Co

JUDGMENT

See Mee Chun JCA:

Introduction

[1] What is the price of loyalty, and conversely, disloyalty? For the Appellant, it was RM10 million, which was the amount stated in the Bond by Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR/party) dated 25 April 2018 (the Bond) signed by her, in the event of breach of the Bond. This then is one of the issues before us, as to the reasonableness or otherwise, of the RM10 million Bond.

Parties

[2] The Appellant was the Defendant and had contested in the 14th General Election (GE-14) in the Ampang Parliamentary seat as a PKR candidate and won with a majority vote of 41,956. The Respondent is the Plaintiff in his capacity as the Secretary General of PKR.

Background Facts And Issues

[3] According to the Respondent, on or about 24 February 2020, the Appellant along with 10 other members of parliament announced their resignation from the party without resigning as members of parliament for their respective constituencies. The Respondent sued the Appellant for the payment of RM10 million under the Bond and in the alternative for RM12,049,459.20 under s 71 of the Contracts Act 1950.

[4] At the HC, the Appellant had resisted the claim inter alia, on the basis the Bond was an invalid document and not enforceable against her; she had not signed the Bond and therefore had not consented to it; the Bond was invalid for restricting her constitutional right of freedom of association; and that the RM10 million was an unconscionable amount.

[5] The claim was allowed by the High Court (HC) and this is the appeal by the Appellant.

[6] Before us, the Appellant raised 3 main issues and therefore these grounds including our reference to the grounds of judgment of the HC will only deal with these 3 issues. These issues were:

i. the reasonableness of the RM10 million amount vis-a-vis s 75 of the Contracts Act 1950;

ii. the trigger event of the Bond had not occurred; and

iii. past consideration.

Decision Of The HC

[7] The grounds of judgment of the HC Judge (GOJ) can be seen in encl 22/13-28.

[8] Essentially the HC found the Bond to be an agreement which fulfilled all the requirements of a valid contract under s 2 of the Contracts Act 1950 (paras 6 to 10) and the purpose of the Bond was not to restrict the Appellant's right of association but to instil the importance of loyalty to the party as well as the awareness that the party had made many sacrifices since its formation (para 15). This was after the HC had considered the evidence in Q&A 6 of the Respondent's witness statement as to why the Bond had been executed.

[9] The HC further found the signature on the Bond was that of the Appellant (paras 18 to 19) and there was no evidence that the Appellant had signed the Bond unwillingly (paras 22 to 24).

[10] The HC dealt with the issue of unconscionable amount as follows:

"25. The defendant also alleges that the sum of RM10 million quoted in the bond is excessive and there is no proof that such a money was spent on her for the purpose of being chosen as a candidate.

26. This allegation of the defendant flies in her own face by the express admission by her in the bond that the plaintiff has spent a sum in excess of RM10 million on her. The third recital in the bond states:

"WHEREAS I acknowledge that Parti Keadilan Rakyat by its letter of appointment to me to be a candidate of Parti Keadilan Rakyat and grant me use of the Parti Keadilan Rakyat logo, insignia and Party flag as a candidate of Parti Keadilan Rakyat has provided me substantial value which exceeds Ringgit Malaysia Ten Million (RM10,000,000.00).

27. The defendant is bound by her own admission as provided under s 21 of the Evidence Act 1950:

"Admissions are relevant and may be proved as against the person who makes them or his representative in interest: but they cannot be proved by or on behalf of the person who makes them or by his representative in interest except in the following cases:....

[Emphasis Mine]

28. Apart from the defendant's admissions, it is the court's view that the whole purport of the bond is to deter an elected candidate from being disloyal to the party. This being the case the sum of RM10 million is not an excessive or a punitive sum and will act as a deterrent for any disloyalty. Any amount lesser than this might not be an effective deterrence.

29. The court further rules that the evidence adduced by the plaintiff showing its income and expenditure accounts is not a relevant or a necessary factor in determining this issue."

[Note: Emphasis Is That Of The HCJ]

Our Decision

Trigger Event

[11] We will first deal with the issue of trigger event where the submission of the Appellant was that the events as stipulated in the Bond had not occurred or had not been triggered. This is because if there is no such trigger event, there would be no breach of the Bond and the issue of reasonableness of the RM10 million will not arise.

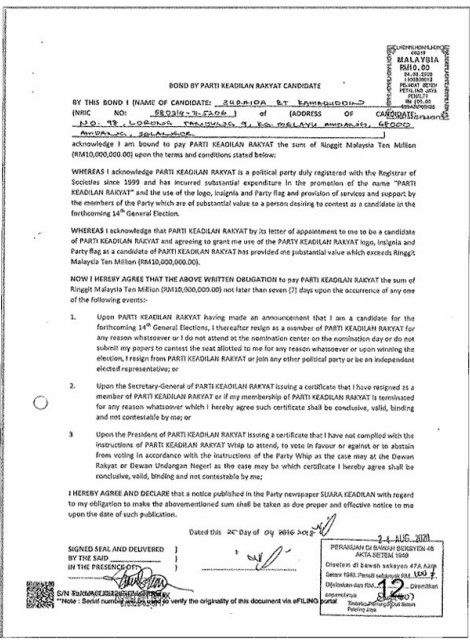

[12] We reproduce the provisions of the Bond in encl 23/12 as follows:

[13] It was contended by the Appellant that in order for the Bond to be enforced, the conditions in unnumbered para 4(2) must have been triggered or had occurred. These relate to the issuance of a certificate that the Appellant has resigned or that her membership is terminated. In para 12 of the statement of claim, it was stated that the Appellant had resigned and in para 14, that the Appellant was terminated. There was also no certificate issued and what was exhibited was a certification of authentication of resolution. The question further arises if the Appellant had resigned, how then could she have been terminated? Thus, the submission was that the trigger event in (2) had not occurred.

[14] The aforesaid paras 12 and 14 of the statement of claim in encl 39/634 (non pdf) are set out below:

"12. On or about 24 February 2020, the Defendant in a statement with another 10 of the Party's Member of Parliament ("the Defectors") announced her resignation from the Party without resigning as a member of parliament for Ampang.

...

14. On 24 February 2020 the Party's Majlis Pimpinan Pusat ("MPP") approved a resolution to terminate the Defendant's membership in the party with immediate effect. The Plaintiff in his capacity as the Party's Secretary General, issued the Certificate dated 24 July 2020, to confirm that the Defendant's membership in the Party has been terminated."

[Emphasis Added]

[15] We note that in fact, the Appellant in her defence has alluded to her resignation. This can be seen in paras 8.8, 14 and 17 of the statement of defence in encl 39/647, 651 and 652 (non pdf) as follows:

"8.8 Defendan sesungguhnya menegaskan bahawa Defendan bukannya seorang pembelot sepertimana yang dituduh oleh Plaintif. Sebaliknya, Defendan menekankan bahawa ianya bukan keputusan yang mudah untuk Defendan keluar daripada PKR memandangkan pengorbanan Defendan sendiri untuk membangunkan PKR....

...

14. Dalam keadaan sedemikian, Defendan sesungguhnya percaya dan menyatakan bahawa tindakan beliau untuk meletakkan jawatan sebagai ahli dan juga Naib Presiden di dalam PKR...

...

17. Perenggan 12 Pernyataan Tuntutan tersebut adalah diakui setakat mana Defendan telah mengumumkan peletakan jawatan beliau di dalam PKR dan kekal sebagai Menteri Perumahan dan Kerajaan Tempatan dibawah kerajaan Perikatan Nasional."

[Emphasis Added]

[16] From the evidence of the Respondent, it is relying on the Appellant having left the party as the basis for enforcing the Bond. Refer to Q&A 8 in encl 23/6869 as follows:

"S8: Sila terangkan kepada Mahkamah apakah tindakan yang telah dilakukan oleh Defendan yang menyebabkan beliau berada dalam suatu keadaan di mana beliau perlu membayar pampasan tersebut kepada Parti tersebut?

J8: Defendan telah membuat keputusan untuk keluar parti pada 24 Februari 2020, setelah Defendan telah menang dalam PRU14 dan dipilih sebagai Ahli Parlimen bagi kawasan pilihan raya P.99 Ampang.

Rujuk: Pernyataan di laman Facebook Azmin Ali bertarikh 24 Februari 2020, Ikatan Dokumen Bersama Bahagian B m/s 6, ditanda sebagai Tindakan sedemikian telah meletakkan Defendan dalam keadaan di mana beliau berkewajipan untuk membayar pampasan dalam amaun RM10,000,000.00 kepada Parti tersebut, sebagaimana yang dipersetujui di antara Defendan dan Parti tersebut dalam perenggan 1, Ikatan Bon tersebut. "

[17] This is consistent with the Respondent's para 12 of the statement of claim, and the Appellant's statement of defence in paras 8.8, 14 and 17.

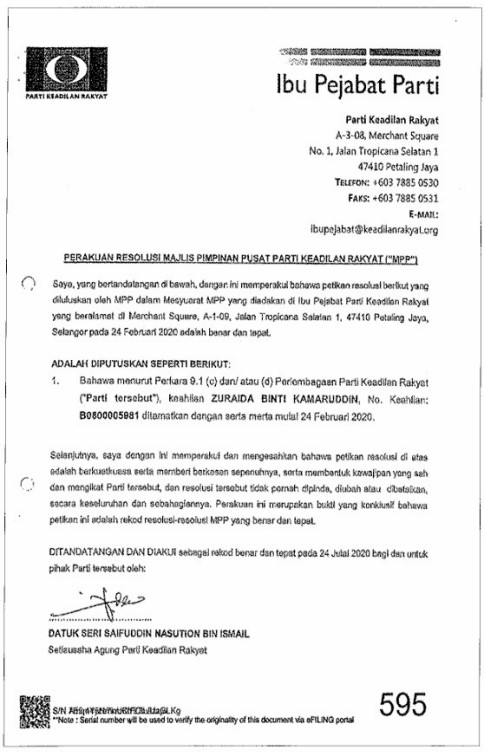

[18] On there being no certificate issued by the Secretary General of PKR as required under (2) of the Bond, we refer to the Perakuan Resolusi dated 24 July 2020 in encl 24/349 as reproduced below:

[19] We find this to be sufficient evidence of there being a resolution of the MPP of PKR effective on 24 February 2020. That resolution states as follows:

'ADALAH DIPUTUSKAN SEPERTI BERIKUT:

1. Bahawa menurut Perkara 9.1 (c) dan/atau (d) Perlembagaan Parti Keadilan Rakyat ("Parti tersebut"), keahlian ZURAIDA BINTI KAMARUDDIN No Keahlian: B0800005981 ditamatkan dengan serta merta mulai 24 Februari 2020"

[20] We further refer to the sentence "Perakuan ini merupakan bukti yang konklusif bahawa petikan ini adalah rekod resolusi-resolusi MPP yang benar dan tepat. This is the evidence of the record of the resolution.

[21] The existence of the resolution is as averred in para 14 of the statement of claim referred to earlier and is further confirmed by the evidence of the Respondent in Q&A 26. We set out the relevant part of that evidence from encl 23/89:

"S26: Apakah tindakan yang diambil oleh Parti tersebut setelah pembelotan Defendan?

J26: Pada 24 Februari 2020 Majlis Pimpinan Pusat Parti ("MPP") telah meluluskan resolusi untuk melucutkan keahlian Defendan dalam Parti tersebut dengan serta merta. Plaintif dalam jawatannya sebagai Setiausaha Agung Parti, mengeluarkan Sijil bertarikh 24 Julai 2020, untuk mengesahkan bahawa keahlian Defendan dalam Parti tersebut telah ditamatkan.

Parti tersebut menerusi peguamnya mengeluarkan surat tuntutan bertarikh 7 Ogos 2020 yang memerlukan Defendan untuk membayar jumlah RM10,000,000.00 menurut terma-terma Bon tersebut. Parti tersebut juga telah menerbitkan notis tuntutan di akhbar Parti tersebut dan/atau portal berita Parti tersebut, Suara Keadilan pada 29 Julai 2020.

Defendan telah gagal, enggan dan/atau abai untuk membayar sama sekali jumlah tersebut sebanyak RM10,000,000.00 atau sebahagian daripadanya. Oleh yang demikian, saya telah mengambil tindakan ini sebagai Pegawai Awam Parti tersebut untuk membuat tuntutan jumlah sebanyak RM10,000,000.00 dari Defendan untuk Parti tersebut."

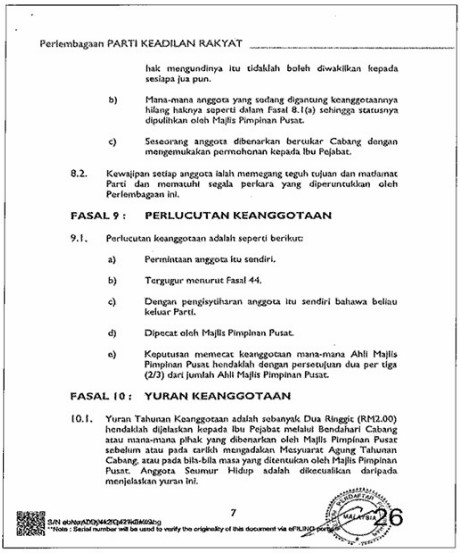

[22] The reference to "menurut perkara 9.1 (c) dan/atau (d) Perlembagaan keahlian... ditamatkan" is also consistent with the manner of perlucutan keanggotaan in the party's constitution in encl 23/26 as follows:

[23] We would therefore conclude on this issue that the event triggering the obligation to enforce the Bond has occurred. Pursuant to unnumbered para 4, the Appellant has agreed to pay the stated amount not later than 7 days upon the occurrence of the event in (2):

"NOW I HEREBY AGREE THAT THE ABOVE WRITTEN OBLIGATION to pay PARTI KEADILAN RAKYAT the sum of RinggitMalaysia Ten Million (RM10,000,000.00) not later than seven (7) days upon the occurrence of any one of the following events:-..."

[Emphasis Added]

[24] Hence, we agree with the finding of the HCJ that there had been a breach of the Bond. The question is the reasonableness of the stipulated amount in the Bond.

Reasonableness Or Otherwise Of The Bond Amount

[25] It will be recalled that the HCJ found that RM10 million was not excessive as the purpose of the Bond was to deter an elected candidate from being disloyal to the party such that any lesser amount would not be an effective deterrence. The issue raised by the Appellant was that the HCJ did not consider whether the amount was reasonable. It was submitted that such an amount is unreasonable, excessive and exorbitant.

[26] Section 75 of the Contracts Act 1950 (the Act) provides as follows:

"Compensation for breach of contract where penalty stipulated for

When a contract has been broken, if a sum is named in the contract as the amount to be paid in case of such breach, or if the contract contains any other stipulation by way of penalty, the party complaining of the breach is entitled, whether or not actual damage or loss is proved to have been caused thereby, to receive from the party who has broken the contract reasonable compensation not exceeding the amount so named or, as the case may be, the penalty stipulated for."

[Emphasis Added]

[27] In this regard, the Federal Court in Cubic Electronics Sdn Bhd v. Mars Telecommunications Sdn Bhd [2019] 2 MLRA 83 has laid down the principles as to what constitutes reasonable compensation and whether actual loss has to be proven.

[28] Cubic too had set out the prior position (our emphasis) as enunciated in Selva Kumar Murugiah v. Thiagarajah Retnasamy [1995] 1 MLRA 188 and Johor Coastal Development Sdn Bhd v. Constrajaya Sdn Bhd [2009] 1 MLRA 654. At p 104, the following was stated:

"[61] And presently the local position has always been that an innocent party in a contract that has been breached, cannot recover simpliciter the sum fixed in a damages clause whether as penalty or liquidated damages. He must prove the actual damage he has suffered unless his case falls under the limited situation where it is difficult to assess actual damage or loss. (See: Selva Kumar Murugiah v. Thiagarajah Retnasamy [1995] 1 MLRA 188, approving the Privy Council decision in Bhai Panna Singh v. Bhai Arjun Singh AIR 1929 PC 179).

[62] As such the courts have always insisted that actual damage or reasonable compensation must be proved in accordance with the principles set out in Hadley v. Baxendale [1854] 9 Exch 341 (See: Johor Coastal Development Sdn Bhd v. Constrajaya Sdn Bhd [2009] 1 MLRA 654 at p 663).

[63] Accordingly, the effect is that no provision in a contract by way of liquidated damages in this country is recoverable in a similar manner as it would have been under the pre-Cavendish (supra) English law since in every case the court has to be satisfied that the sum payable is reasonable.

[64] Having noted the foregoing, does this then mean that for every case where the innocent party seeks to enforce a clause governing the consequences of breach of a primary obligation, it invariably has to prove its actual loss or damage? Selva Kumar and Johor Coastal seem to answer in the affirmative, unless the case falls under the limited situation where it is difficult to assess actual damage or loss."

[Emphasis Added]

[29] Having asked the question in para 64, the Federal Court answered as follows at pp 104-105:

"[65] With respect and for reasons we shall set out below, we are of the view that there is no necessity for proof of actual loss or damage in every case where the innocent party seeks to enforce a damages clause. Selva Kumar and Johor Coastal should not be interpreted (as what the subsequent decisions since then have done) as imposing a legal straitjacket in which proof of actual loss is the sole conclusive determinant of reasonable compensation. Reasonable compensation is not confined to actual loss, although evidence of that may be a useful starting point.

[66] As for our reasons we begin by saying that in view of the legislative history of s 75 of the Act which need not be elaborated in this Judgment, we are of the considered opinion that there is nothing objectionable in holding that the concepts of "legitimate interest" and "proportionality" as enunciated in Cavendish are relevant in deciding what amounts to 'reasonable compensation' as stipulated in s 75 of the Act. Ultimately, the central feature of both the Cavendish case and s 75 of the Act is the notion of reasonableness. Indeed, theParkingEye Limited v. Beavis [2015] UKSC 67 judgment is replete with instances where the United Kingdom Supreme Court conflated "proportionality" with "reasonableness" (see: ParkingEye (supra) at paras [98], [100], [108], [113] and [193])."

[Emphasis Added]

[30] It went on to say at p 105:

"[68] Consequently, regardless of whether the damage is quantifiable or otherwise, it is incumbent upon the court to adopt a common sense approach by taking into account the legitimate interest which an innocent party may have and the proportionality of a damages clause in determining reasonable compensation. This means that in a straightforward case, reasonable compensation can be deduced by comparing the amount that would be payable on breach with the loss that might be sustained if indeed the breach occurred [Emphasis Added]. Thus, to derive reasonable compensation there must not be a significant difference between the level of damages spelt out in the contract and the level of loss or damage which is likely to be suffered by the innocent party.

[69] Notwithstanding the foregoing, it must not be overlooked that s 75 of the Act provides that reasonable compensation must not exceed the amount so named in the contract. Consequently, the impugned clause that the innocent party seeks to uphold would function as a cap on the maximum recoverable amount."

[Emphasis Added]

[31] The question of burden of proof was dealt with at p 106:

[71] If there is a dispute as to what constitutes reasonable compensation, the burden of proof falls on the defaulting party to show that the damages clause is unreasonable or to demonstrate from available evidence and under such circumstances what comprises reasonable compensation caused by the breach of contract. Failing to discharge that burden, or in the absence of cogent evidence suggesting exorbitance or unconscionability of the agreed damages clause, the parties who have equality of opportunity for understanding and insisting upon their rights must be taken to have freely, deliberately and mutually consented to the contractual clause seeking to preallocate damages and hence the compensation stipulated in the contract ought to be upheld.

[72] It bears repeating that the court should be slow to refuse to give effect to a damages clause for contracts which are the result of thorough negotiations made at arm's length between parties who have been properly advised. The court ought to be alive to a defaulting promisor's natural inclination to raise "unlikely illustrations" in argument to show substantial discrepancies between the sum due under the damages clause and the loss that might be sustained in the unlikely situations proposed by the promisor (see: Philips Hong Kong Ltd at p 59) so as to avoid its liability to make compensation pursuant to that clause. (See: Tham, Chee Ho, "Non-compensatory Remedies", The Law of Contract in Singapore, Ed., Andrew Phang Boon Leong, (Singapore: Academy Publishing, 2012), pp 1645-1862 at p 1654.)

[Emphasis Added]

[32] Finally, at pp 106-107, the Federal Court summarised the principles as below:

"[74] In summary and for convenience, the principles that may be distilled from hereinabove are these:

...

(d) In determining what amounts to "reasonable compensation" under s 75 of the Act, the concepts of "legitimate interest" and "proportionality" as enunciated in Cavendish are relevant;

(e) A sum payable on breach of contract will be held to be unreasonable compensation if it is extravagant and unconscionable in amount in comparison with the highest conceivable loss which could possibly flow from the breach. In the absence of proper justification, there should not be a significant difference between the level of damages spelt out in the contract and the level of loss or damage which is likely to be suffered by the innocent party;

(f) Section 75 of the Act allows reasonable compensation to be awarded by the court irrespective of whether actual loss or damage is proven. Thus, proof of actual loss is not the sole conclusive determinant of reasonable compensation although evidence of that may be a useful starting point;

(g) The initial onus lies on the party seeking to enforce a damages clause under s 75 of the Act to adduce evidence that firstly, there was a breach of contract and that secondly, the contract contains a clause specifying a sum to be paid upon breach. Once these two elements have been established, the innocent party is entitled to receive a sum not exceeding the amount stipulated in the contract irrespective of whether actual damage or loss is proven subject always to the defaulting party proving the unreasonableness of the damages clause including the sum stated therein, if any; and

(h) If there is a dispute as to what constitutes reasonable compensation, the burden of proof falls on the defaulting party to show that the damages clause including the sum stated therein is unreasonable."

[Emphasis Added]

[33] There was also mention of the concepts of legitimate interest and proportionality as enunciated in Cavendish Square Holding BV v. Talal El Makdessi which was heard together with ParkingEye Limited v. Beavis [2016] 2 All ER 519. Much discussion went into the issue of what made a contractual provision penal in nature and at p 538:

"[32] The true test is whether the impugned provision is a secondary obligation which imposes a detriment on the contract-breaker out of all proportion to any legitimate interest of the innocent party in the enforcement of the primary obligation. The innocent party can have no proper interest in simply punishing the defaulter. His interest is in performance or in some appropriate alternative to performance. In the case of a straightforward damages clause, that interest will rarely extend beyond compensation for the breach, and we therefore expect that Lord Dunedin's four tests would usually be perfectly adequate to determine its validity, But compensation is not necessarily the only legitimate interest that the innocent party may have in the performance of the defaulter's primary obligations...."

[Emphasis Added]

[34] For context, Lord Dunedin's four tests as in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v. New Garage & Motor Co Ltd [1915] AC 79 in para 21 of Cavendish at pp 532 and 533:

"[21]... In his speech, Lord Dunedin formulated four tests 'which, if applicable to the case under consideration, may prove helpful, or even conclusive' ([1915] AC 79 at 87, [1914-15] All ER Rep 739 at 742). They were: (a) that the provision would be penal if 'the sum stipulated for is extravagant and unconscionable in amount in comparison with the greatest loss that could conceivably be proved to have followed from the breach'; (b) that the provision would be penal if the breach consisted only in the non-payment of money and it provided for the payment of a larger sum; (c) that there was 'a presumption (but no more)' that it would be penal if it was payable in a number of events of varying gravity; and (d) that it would not be treated as penal by reason only of the impossibility of precisely pre-estimating the true loss."

At p 533, Cavendish was quick to note in para 22 that the four tests are not rules but only considerations (line c).

[35] In Chitty on Contracts (thirty-third edition) it was opined at para 26-211, p 1930 with reference to ParkingEye that there can be permissible deterrence in protecting a legitimate interest or broader interests. It goes further by referring to Cavendish at para 26-214 at p 1933 that an agreed damages clause or other type of clause that falls within the scope of the penalty doctrine will be valid if it is designed to protect the legitimate interest of the innocent party and the amount involved is not extravagant or unconscionable in proportion to that interest.

[36] Paragraphs 70 and 74(g) of Cubic cast the burden on the Respondent as the party seeking to enforce a clause under s 75 of the Act to prove a breach and that the contract contains a clause specifying a sum to be paid upon breach. As found earlier, there was a trigger event and the Bond contains the agreement of the Appellant to pay the amount of RM10 million.

[37] As the Appellant had breached the Bond, the Respondent is the innocent party and Cubic has held in para 65 that there is no necessity for proof of actual loss or damage. It falls back on whether the RM10 million is reasonable compensation, where legitimate interest and proportionality, as stated in Cavendish and approved in Cubic, can be considered.

[38] We are reminded further of Cavendish where the true test is whether the impugned provision is a secondary obligation which imposes a detriment on the contract-breaker who is the Appellant out of proportion to any legitimate interest of the innocent party who is the Respondent in the enforcement of the primary obligation.

[39] We refer to Q&A 6, 12 and 16 of the Respondent which inter alia states that the party has incurred substantial costs and expenditure in promoting the name, political brand and Marks of the party, the sum of RM10 million takes into account the legitimate interest of the party, the value of the party name, reputation and the loss of goodwill to the party's political brand. Such loss of goodwill was acquired through great costs, expenditure and efforts since the inception of the party.

[40] Q&A 6 (encl 23/67-68), 12 (encl 23/70-71) and 16 (encl 23/27) are set out below:

"S6: Apakah tujuan Ikatan Bon tersebut disediakan?

J6: Ikatan Bon tersebut disediakan untuk memastikan Defendan yang akan bertanding dalam Pilihan Raya Umum Ke-14 (PRU14) atas tiket Parti memahami dan mengakui bahawa Parti tersebut telah menanggung perbelanjaan yang besar untuk mempromosikan nama "Parti Keadilan Rakyat" dan penggunaan logo, lambang, symbol dan bendera Parti tersebut serta pemberian perkhidmatan dan sokongan oleh anggota-anggota Parti adalah sangat bernilai bagi seseorang, termasuk Defendan, yang ingin bertanding sebagai calon atas tiket Parti tersebut, dalam PRU14. Ikatan Bon tersebut juga disediakan bagi memastikan Defendan memahami dan mengakui bahawa pelantikan Defendan sebagai calon dan pemberian kebenaran kepada Defendan untuk mengguna pakai logo, lambang, symbol dan bendera Parti adalah bernilai lebih daripada RM10,000,000.00.

...

S12: Apakah asas kepada penentuan pampasan dalam amaun RM10,000,000.00 dan bukannya amaun yang lain?

J12: Jumlah RM10,000,000.00 merupakan suatu anggaran yang tulen bagi menjamin kepentingan sah Parti tersebut, nama baik dan reputasi Parti tersebut.

Asas penganggaran tersebut adalah berdasarkan faktor-faktor yang berikut: (i) kos dan perbelanjaan penyelanggaran pejabat dan struktur organisasi sebagai sebuah parti nasional selama satu tahun; (ii) kehilangan ahli, aktivis dan penyokong serta kehilangan keupayaan untuk merekrut ahli baru oleh Parti tersebut; (iii) kehilangan keupayaan menjana tajaan dan mengumpul dana; (iv) kerosakan kepada rangkaian komunikasi Parti tersebut; dan (v) kehilangan dan kemusnahan nilai jenama Parti tersebut dan nama baik tanda Parti tersebut berdasarkan kos sejarah untuk membangunkannya sejak tahun 1998.

...

S16: Apakah jawapan kamu kepada cadangan Defendan bahawa amaun pampasan sebanyak RM10,000,000.00 adalah terlampau tinggi dan oleh itu adalah bersifat suatu denda?

J16: Seperti mana yang saya telah pun terangkan sebelum ini, amaun RM10,000,000.00 adalah suatu anggaran yang tulen. Ianya bukanlah mengikut suka hati Parti tersebut. Sebaliknya, penentuan amaun sedemikian adalah berasaskan beberapa faktor yang telah pun diterangkan sebelum ini. Hakikatnya, kita tidak boleh menafikan bahawa tindakan seseorang calon seperti Defendan mengkhianati Parti tersebut adalah membawa kerosakkan dan kerugian kepada Parti tersebut.

Namun, adalah sukar untuk Parti tersebut membuat suatu penentuan secara tepat apakah nilai kerosakan dan kerugian yang sebenar dan yang perlu dipampas oleh mereka yang bertanggungjawab. Oleh itu, setelah mempertimbangkan pelbagai faktor, Biro Politik Parti tersebut telah menentukan amaun RM10,000,000.00 sebagai suatu jumlah pra-anggaran yang telah pun dipersetujui oleh Defendan.

..."

[41] At Q&A 13 (encl 23/71-76), the Respondent had given evidence of the estimated damage to the political brand, reputation and goodwill to obtain financial and other support which include the following:

i. The annual costs and expenses for operating the headquarters and organization structure as a national party at RM1,952,584.72;

ii. The voluntary services provided by members and volunteers including those acting as canvassing agents, polling and counting agents which would costs at least RM152,670,000.00 if the party is to pay 100 workers at RM150.00 per day for 14 days election campaign for 222 parliament and 505 state assembly seats;

iii. The total loss of goodwill in raising funds and financial support for the 5 years after GEM which is estimated at RM221,800,000.00;

iv. The cost of setting up and maintaining the social media network and communication system at RM223,984.20.

[42] In cross-examination (encl 23/158-160), the Respondent explained as follows:

"Nizamuddin Hamid/Nurul Najwa: Seperti terma yang suka digunakan oleh rakan Datuk Seri dalam Parti, apa formula 10 juta ni. Apa formula dia?

...

Saifuddin Nasution: Baik. Yang Arif, pertamanya, Parti mempunyai beberapa peringkat dan tahap. Satu, Majlis Pimpinan Pusat. Dua, Majlis Pimpinan Negeri. Tiga, kepimpinan diperingkat cabang. Empat, jawatankuasa diperingkat kerusi Parlimen, yang Parti bertanding. Lima, jawatankuasa di peringkat Dewan Undangan Negeri di mana Parti bertanding dan meletak calon. Seterusnya, sayap Angkatan Muda, sayap Wanita.

Kemudian, kita ada Jawatankuasa Pilihan Raya. Kesemua struktur Parti ini, Yang Arif, mempunyai keupayaan dan aktiviti mengumpulkan dana mengikut cara masing-masing, sama ada melalui crowdfunding, ataupun melalui penganjuran majlis makan malam, ataupun melalui penerimaan sumbangan daripada simpati-simpati. Mereka bukan anggota Parti Yang Arif, tetapi mereka memberikan sumbangan.

Berasaskan kepada keupayaan ini Yang Arif, saya bagi contoh, Majlis Pimpinan Pusat misalnya, dalam satu tahun, melalui program crowdfunding, penganjuran majlis makan malam, terimaan daripada sumbangan individu atau mana-mana syarikat Yang Arif. Kami mempunyai keupayaan mengumpul sehingga satu juta, satu juta setengah, atau dua juta Yang Arif, setiap tahun. Dan, kalau kita kalikan dengan lima tahun, satu penggal Parlimen Yang Arif, itu saja sudah memberikan anggaran 10 juta, Yang Arif.

Begitu juga, di peringkat Parlimen Yang Arif, setiap bulan mereka mampu, setiap hari mereka mampu mengumpul sehingga dua ribu atau tiga ribu melalui sumbangan crowdfunding ataupun simpati-simpati. Jadi itu memberikan dalam setahun mereka mampu mengumpul antara 40 ribu hingga 50 ribu Yang Arif. Dan itu memberikan setahun, kemudian kita kalikan dengan dua 222 cabang. Parti Keadilan adalah parti nasional Yang Arif. Kami berdaftar di kesemua 222 Parlimen. Kalau satu kawasan Parlimen kami berupaya mengumpul dana sebulan 50 ribu atau setahun 50 ribu Yang Arif, kalikan dengan 222 cabang, kalikan dengan lima tahun. Itu akan memberikan angka yang cukup besar Yang Arif.

Begitu juga sayap Pemuda, sayap Wanita, kemudian di peringkat Dewan Undangan Negeri....

Berasaskan formula ini Yang Arif, kutipan bulanan, kutipan tahunan, kita kalikan dengan dua 222 cabang, 222 sayap Pemuda, 222 sayap Wanita, kepimpinan Pusat, Pemuda Pusat, Wanita Pusat, peringkat Parlimen, peringkat Dewan Negeri, dan kita tabulate-kan untuk tempoh lima tahun Yang Arif. Angka 200 juta itu adalah angka yang reasonable, genuine, berasaskan pengalaman 20 tahun Parti Keadilan bergerak Yang Arif.

...

Nizamuddin Hamid/Nurul Najwa: Terima kasih untuk perkongsian formula tersebut, Datuk Seri. Jadi soalan saya berdasarkan formula tersebut, saya cadangkan, tidak wajar beban kemampuan penjanaan dana Parti Keadilan Rakyat diletakkan kepada seseorang calon kerana formulanya mengambil kira keseluruhan, kesemua peringkat, kesemua cabang, kesemua peringkat Wanita yang utama, Pemuda, tetapi hendak, itu formulanya. Saya cadangkan ianya tidak wajar, it's unreasonable, kerana berdasarkan formula yang mengambil kira semua ini, jumlah 10 juta tersebut hendak dikenakan kepada seorang sahaja. Saya cadangkan itu tidak wajar. Setuju tak dengan saya?

Saifuddin Nasution: Saya tak setuju.

...

Nizamuddin Hamid/Nurul Najwa: Boleh Datuk Seri kongsi formula bagaimana gaji seorang menteri yang tidak sampai sepenggal, seperti Defendan, tak cukup sepenggal, hampir cukup, tidak cukup penuh sepenggal, boteh membayar jumlah 10 juta ringgit.

Saifuddin Nasution: Baik, dua bahagian. Yang pertama, 10 juta itu cuma lima peratus Yang Arif, daripada 200 juta. Anggaran lima tahun, keupayaan kutipan dana Parti. Lima peratus sahaja. Kedua Yang Arif, angka 10 juta itu, seperti Yang Arif bertanya, adalah keputusan..."

[Emphasis Added]

[43] In re-examination (encl 23/173), on the issue of one person having to bear all, it was explained:

"Navpreet Singh: Soalan yang ditujukan kepada Datuk Seri semasa cross-examination ialah, "lanya tidak wajar kemampuan penjanaan dana Parti diletakkan ke atas seorang calon sahaja kerana ini mengambil kira kesemua organisasi Parti."

Datuk Seri tidak bersetuju dengan cadangan ini. Tolong jelaskan kenapa.

Saifuddin Nasution: Yang Arif, parti ni berusaha untuk mengumpul dana kerana penyertaan Parti dalam proses pilihan raya menelan belanja yang sangat besar. Yang Arif, dana parti ini akan terkumpul melalui pelbagai cara dan pelbagai saluran.

Pemimpin-pemimpin Parti lebih-lebih lagi memikul tanggungjawab yang lebih berat berbanding anggota biasa ataupun simpati-simpati. Kerana itu saya mengambil, menjawab seperti mana yang disebut tadi."

[44] It was submitted that the RM10 million is not confined to one parliamentary seat but that as a national party, the damage is done to all 222 divisions, at each of the levels in the organisation.

[45] Although it is not necessary for there to be proof of actual loss and damage, the Respondent had tried to establish its losses where inter alia it had incurred substantial costs and expenditure in promoting the political brand and Marks of the party. There was also the legitimate interest it had as a political party.

[46] The above was also to show the legitimate interest and proportionality where RM10 million was 5% of RM200 million in building up the party name, goodwill and Marks. In that sense, it was also said to be not unconscionable.

[47] Another aspect of the legitimate interest of the party, being political in nature, was the consequence of the Appellant resigning and joining another political party. The Appellant was regarded as a defector. The effects of her defection to join another political party led to the collapse of the Government of the day and political instability which are further explained by the Respondent in Q&A 25.1 and 25.2 (encl 23/84-88).

[48] The thrust of the Respondent's submission ultimately was that the RM10 million was reasonable compensation within the meaning of s 75 of the Act.

[49] Since the Appellant was disputing that this was reasonable compensation, it was her burden to prove otherwise. We are of the considered opinion that this burden has been discharged for the following reasons.

[50] Although there is a legitimate interest of the party to maintain its political position, the RM10 million is out of proportion to such interest of the party in the enforcement of the obligation of the Bond. As explained by the Respondent, the RM10 million is not confined to one parliamentary seat but as a national party, the damage is done to all 222 divisions. Therefore, it is not reasonable for the Appellant to take on the liability of the RM10 million single-handedly when the formula of the RM10 million was based on 222 divisions for the party at a national level. Seen in this light, the amount is also not proportionate.

[51] We further say the amount is not proportionate as the undisputed 22 months of the Appellant's service as a member of parliament had not been considered.

[52] The HCJ had upheld the RM10 million as a deterrent for any disloyalty and any lesser amount might not be an effective deterrence. However, what was not considered was whether this was a reasonable compensation and s 75 of the Act and the relevant authorities such as Cubic and Cavendish were not discussed.

[53] To conclude on this issue, after considering the evidence and the principles of legitimate interest and proportionality, we find the RM10 million cannot be construed as reasonable compensation. We find it to be unreasonable, extravagant, unconscionable and not in proportion to the legitimate interest sought to be protected.

Admission

[54] The HCJ had also found that the Appellant had admitted the substantial value provided by the party far exceeds RM10 million in the recital to the Bond:

"WHEREAS I acknowledge that PARTI KEADILAN RAKYAT by its letter of appointment to me be a candidate of PARTI KEADILAN RAKYAT and agreeing to grant me use of the PARTI KEADILAN RAKYAT logo, insignia and Party flag as a candidate of PARTI KEADILAN RAKYAT has provided me substantial value which exceeds Ringgit Malaysia Ten Million (RM10,000,000.00).

[Emphasis Added]

[55] Section 23 of the Evidence Act 1950 which recognises that "admissions are relevant and may be proved as against the person who makes them" was referred to.

[56] The Respondent referred to Luggage Distributors (M) Sdn Bhd v. Tan Hor Teng & Anor [1995] 1 MLRA 496 where this Court said at p 513:

"It is a cardinal rule in the interpretation of contracts that recitals may be taken into account as an aid to construction and this is all the more so where there is ambiguity in the document. Further, in an appropriate case, the court may construe a recital as carrying with it an obligation to carry into effect that which is recited."

[57] Greer And Another v. Kettle [1938] AC 156, at p 171 was also cited:

"Estoppel by deed is a rule of evidence founded on the principle that a solemn and unambiguous statement or engagement in a deed must be taken as binding between parties and privies and therefore as not admitting any contradictory proof...."

[58] We were then referred to The Interpretation of Contracts (6th edn) by Sir Kim Lewison at p 560 that "Where a recital of fact is intended to be a statement of all parties, all parties are estopped from denying the truth of the recital. But where the recital is the statement of one party only, only that party is so estopped." Greer was cited by the learned author to support that proposition.

[59] The Appellant referred to a further passage on the same page that "An estoppel will only arise where the recital recites a statement of fact. It will not arise where the recital purports to state the legal effect of the document". Here, very clearly the recital relates to a statement of fact that the party has provided the Appellant substantial value exceeding RM10 million. It was not a statement of legal effect by the Appellant. However, the very last passage ends with "This is a reflection of the principle that although the parties are free to contract in whatever terms they please, the legal effect of what they have agreed is a question of law for the court". Essentially this leaves the interpretation of that admission to the court where we are of the opinion that the admission must be read in light of what constitutes reasonable compensation.

[60] This equally applies to the other admissions which were said to have been made by the Appellant on the efforts and difficulty in obtaining funds for the party. Refer to para 76(c) (i) to (iv) of the Respondent's written submission dated 2 September 2024.

What Then Is The Reasonable Compensation

[61] Our finding that RM10 million is not reasonable compensation does not absolve the Appellant from any liability. The fact and finding remains that the Appellant breached the Bond and it follows that the Respondent is entitled to some reasonable compensation but not RM10 million.

[62] It behoves upon us to determine what the reasonable compensation ought to be. We are of the opinion that such an amount ought to consider the maximum amount to be spent in GE-14 for a parliamentary seat which is RM200,000.00, the Appellant's 22 months as a member of parliament and the contribution of the Appellant in the party and the GE-14 election campaign. We think that these are valid factors which go towards proportionality. Towards this end, we find RM100,000.00 to be reasonable compensation.

Past Consideration

[63] The issue of past consideration was also raised. We find that this was not pleaded in the defence nor raised in the memorandum of appeal and as such will not be considered.

Conclusion

[64] For all the above reasons, we find that the HCJ was plainly wrong to have allowed the Respondent's claim of RM10 million. However, we cannot ignore the breach of the Bond by the Appellant and we vary the amount payable to RM100,000.00. The appeal is partly allowed and the decision of the HC is varied to that extent. We award costs of RM40,000.00 to the Appellant, subject to allocatur.