Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Lee Swee Seng, Supang Lian, Ahmad Zaidi Ibrahim JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: W-01(A)-564-09-2021]

30 September 2024

Administrative Law: Judicial review — Certiorari — Order of certiorari to quash decisions imposing anti-dumping duties at rate of 3.62% on steel concrete reinforcing bar products (Rebar) originating or exported from applicant in Republic of Turkey — Constructed "export price" and calculations of dumping margin — Whether anti-dumping duties wrong in law both procedurally and in substance — Whether decisions irrational and illegal and ought to be quashed and set aside

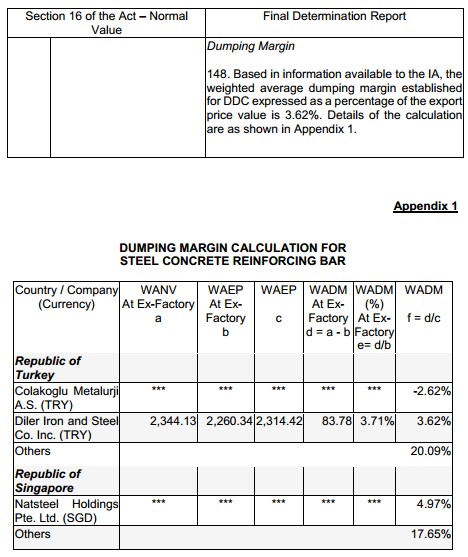

The present dispute was over the import of steel concrete reinforcing bar products ("Rebar") to Malaysia by Malaysian importers from a company in Turkey. Some members of the Malaysian Steel Association were aggrieved with the sale of the Rebar in Malaysia's domestic market from Turkey which they said were sold at a price below the "normal value" of the product in Turkey and thus, "dumping" in nature. The problem here was that the producer in Turkey did not export directly to importers in Malaysia but through its wholly-owned subsidiary in Turkey. At the core of the complaint was the calculation of the "export price" because the difference between that and the "normal value" of the product would be the Dumping Margin if the "normal value" exceeded the "export price". The relevant statute providing for this imposition of Anti-Dumping Duties ("AD Duties") was the Countervailing and Anti-Dumping Duties Act 1993 ("Act") and the Regulations made thereunder and Malaysia's international commitments under the World Trade Organisation Anti-Dumping Agreement ("WTO AD Agreement"). The remedy in the form of duties imposed would level the competition and disincentivise the exporter from trying to injure the domestic market of any importing country with respect to the same or comparable merchandise. In this instance, the Investigating Authority ("IA") had used the internal sale price between the producer, Diler Miler Celik Endustru Ve Ticaret AS ("DDC") in Turkey and its related wholly-owned subsidiary, Diler Dis Ticaret Anomin Sirketi ("DDT"), as the "export price" of the merchandise. DDC applied for judicial review at the High Court seeking an order of certiorari to quash: (i) the Minister of Finance's decision to impose AD Duties at the rate of 3.62% on Rebar originating or exported from DDC in the Republic of Turkey from 22 January 2020 to 21 January 2025 as set out in the Customs (Anti-Dumping Duties) Order 2020 [PU(A) 22 dated 21 January 2020]; and (ii) the Minister of International Trade and Industry's decision and/or recommendation to impose AD Duties at the rate of 3.62% on Rebar originating or exported from DDC in the Republic of Turkey as set out in the Notice of Affirmative Final Determination [PU(B) 46 dated 21 January 2020] and the Final Determination Report of an AD Duty Investigation dated 7 January 2020 respectively ("Impugned Decisions"). The High Court dismissed the application, resulting in the present appeal.

Held (allowing DDC's appeal):

(1) The objective price in the invoices between DDC and DDT was not the point because it was unreliable as being transactions between related parties and it did not capture the "export price" at the point of first resale of the merchandise to an independent buyer in the Malaysian buyers. After all, one was not dealing with what was called a "standard situation" where a comparison was made directly between the "export price" being the transacted price at which the merchandise was sold by a producer/exporter in the exporting country to an importer in the importing country. The High Court erred in affirming the decision of the respondents to take the internal sale price between the producer and its wholly-owned subsidiary as the "export price" when the same would not comport with the rationale of dumping and when to do so would be against the requirement of the Act. The final decision arrived at in AD Duties imposed was thus an error of law rendering the decision illegal and irrational for breach of art 2.1 of the WTO AD Agreement, which was the international law on trade that Malaysia had agreed to be bound by. (paras 41-43)

(2) The constructed "export price" that was to be determined for the purpose of imposing the AD Duties should be following the formula as set out in s 17 of the Act being the transacted price as the starting point under s 17(2) of the Act, of the subject merchandise when first resold to an independent buyer and allowance as in a working backwards would be made "for all costs incurred between importation and resale" under s 17(3) of the Act. Clearly, by using the price at which the subject merchandise was sold by DDC the producer to its related company DDT as the "export price" instead of the price at which it was resold to the first independent buyer in the importing country, the IA had begun on the wrong footing and committed an error of law. Having started wrongly, the correct constructed "export price" could not be arrived at for the simple reason that one could not start off wrongly and yet arrive correctly. The use of "internal pricing" between DDC the producer and its related company DDT was illegal as it was in not in accordance with the statutorily prescribed provision in s 17(2) of the Act and the provisions in arts 2.3 and 2.4 of the WTO AD Agreement to which Malaysia was a party and thus, rendered the decision made in excess of jurisdiction and ultra vires the Act. (paras 66, 69 & 70)

(3) The IA had not seen it necessary to add the duty drawback though it appreciated that the same merchandise for domestic consumption in the country of origin did not enjoy such duty drawback. By misconstruing and not applying s 18 of the Act to arrive at a fair comparison between the constructed "export price" and the "normal value", an error of law had arisen and a wrong Dumping Margin had been arrived at. Therefore, the AD Duties imposed had to be quashed and set aside. (para 82)

(4) The decision of the respondents in insisting to base their calculation of the "export price" on the invoice date of the sales between DDC and DDT, which were internal sales within the exporting country and not on the date of the sales between DDT and the Malaysian importers, was irrational and wrong in law as there was no export to an importing country as yet and so no dumping to begin with. (para 88)

(5) Where the provisions of the Act and the WTO AD Agreement imposed a statutory and contractual duty to provide reasons and to disclose data and information in a decision-making process involving the participation of affected parties, the Court would act to ensure compliance as part of Malaysia's commitment to international trade law under the WTO regime. The process prescribed involving disclosure of the relevant data and information relied upon by the IA, feedback from the party affected, verification exercises undertaken by the IA and reasons for arriving at the determination of the Dumping Margin and a disclosure of the data used in arriving at the calculation of the Dumping Margin as well as the formula used, were all put in place to ensure the integrity of the result reached in the imposition of the AD Duties. There was no proof of dumping from the calculation of the respondents, devoid as it was of details that could be verified by the affected parties like DDC. Therefore, there was no need for this Court to embark on finding whether there was material injury to the domestic market in Malaysia of the subject merchandise and much less a causal link between the dumping and alleged material injury before any AD Duties might be imposed. (paras 121-123)

(6) The constructed "export price" and the calculations of the Dumping Margin and consequently AD Duties , being wrong in law both procedurally and in substance, could not stand and the decisions arrived at with respect to the AD Duties imposed in the Impugned Decisions were irrational and illegal, and ought to be quashed and set aside. (para 124)

Case(s) referred to:

BX Steel Posco Cold Rolled Sheet Co Ltd v. Minister Of Finance & Ors; FIW Steel Sdn Bhd (Intervener) [2020] MLRHU 548 (refd)

Dato Mohamad Yusof A Bakar & Anor v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur [2020] 1 MLRA 545 (refd)

Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur v. Perbadanan Pengurusan Trellises & Ors And Other Appeals [2023] 4 MLRA 114 (refd)

Eng Song Aluminium Industries Sdn Bhd v. Keat Siong Property Sdn Bhd [2018] 6 MLRA 194 (refd)

Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri v. Rainforest Heights Sdn Bhd [2018] MLRHU 1869 (refd)

Metacorp Development v. Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri [2011] 10 MLRH 854 (refd)

Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop Of Kuala Lumpur v. Menteri Dalam Negeri & Ors [2014] 4 MLRA 205 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Countervailing and Anti-Dumping Duties Act 1993, ss 2(5), (6), 16(1), (2)(a), 17(1), (2), (3), 18(1), (5), (8), 25(2), 30(1), (2), (3), (4), (5), 34A(1), 38(4), 44

Rules of Court 2012, O 53 r 3(1)

Other(s) referred to:

Edwin Vermulst, Oxford Commentaries on the GATT/WTO Agreements — The WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement — A Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2005, pp 14-15

Philippe De Baere, Clotilde du Parc and Isabelle Van Damme, The WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement — A Detailed Commentary, Cambridge University Press, 2021, pp 55, 56, 98

Raj Bhala, Modern GATT Law, A Treatise on the Law and Political Economy of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and Other World Trade Organisation Agreements, Volume II, Sweet & Maxwell, 2nd Edn, 2013, Table 66-2

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Dispute Settlement — World Trade Organization 3.5 Anti-dumping Measures, New York and Geneva, 2003, p 8

World Trade Organisation Panel Report — China — Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duty Measures on Broiler Products from the United States, WT/DS427/14, paras 7.91, 7.93

World Trade Organisation Panel Report — China — Definitive Anti-Dumping Duties On X-Ray Security Inspection Equipment From the European Union, WT/DS 425/9, paras 7.416, 7.417, 7.92, 7.93

World Trade Organisation Panel Report — China — Measures Imposing Anti-Dumping Duties on High-Performance Stainless Steel Seamless Tubes (HP-SSST) From Japan and the European Union, WT/DS454 & DS460/AB/R, para 5.133

World Trade Organisation Panel Report — European Union — Anti-Dumping Measures on Biodiesel from Indonesia WT/DS480/R, paras 7.112-7.114

World Trade Organisation Panel Report — European Union — Anti-Dumping Measures on Imports of Certain Fatty Alcohols from Indonesia, WT/DS442/R, paras 7.228-7.229

World Trade Organisation Panel Report — United States — Anti-Dumping Measures on Certain Hot Rolled Steel Products From Japan, WT/DS184/AB/R, para 171

World Trade Organisation Panel Report — United States — Anti-Dumping Measures on Stainless Steel Plate in Coils and Stainless Steel Sheet and Strip from Korea, WT/DS179/R, paras 6.93-6.94

WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement, arts 2.1, 2.3, 2.4, 6.4, 6.7, 6.8, 6.9, 8, 12 WTO General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), art VI.4

Counsel:

For the applicant: Jason Teoh Choon Hui (Ashlyn Lau Hui Qi & Balqis Mohd Nor with him); M/s Jason Teoh & Partners

For the 1st-4th respondents: Kogilambigai Muthusamy; AG's Chambers

For the 5th respondent: Jason Tan Jia Xin (Ng Jack Ming with him); M/s Lee Hishammuddin Allen & Gledhill

JUDGMENT

Lee Swee Seng JCA:

[1] In the field of international trade, States that are members of the World Trade Organisation ("WTO") pledge themselves to be fair to other States whilst promoting their own domestic markets. It is an example of a man, left to his own devices, has a way of gravitating towards promoting his own interest at the expense of others. In international trade, States recognise this danger operating at the international arena where one country and its members may dump its products in another at a price lower than the price in its own home market so as to injure the local market of another country.

[2] Price is no longer what a buyer is prepared to pay for a seller's product. If one sells one's product in another country below the price of that comparable product and trade in one's own country then that is dumping of the product in the importing country. "Dumping" means the importation of merchandise into Malaysia at less than its normal value as sold in the domestic market of the exporting country. If the relevant authorities can show that there is injury caused to the domestic market in the importing country, then anti-dumping duties may be imposed on the exporter for the export of the product to the importing country.

[3] The mischief addressed is to level the playing field for a fair competition such that no one would be able to gain an unfair advantage over another in world trade and in the process cause or threaten to cause a material injury to or to retard the growth of the domestic industry in another member Country.

[4] Whilst the concept is easy to understand, the mechanics and methodology of its calculation are more complicated and as they say the devil is in the details. In the present dispute, it is over the import of Steel Concrete Reinforcing Bar Products ("Rebar") to Malaysia by Malaysian importers from a company in Turkey. Some members of the Malaysian Steel Association ("MSA") were aggrieved with the sale of the Rebar in our domestic market from Turkey which they said were sold at a price below the "normal value" of the product in Turkey and thus Dumping in nature.

[5] The problem here is that the producer in Turkey did not export direct to importers in Malaysia but through its wholly-owned subsidiary in Turkey. At the core of the complaint is the calculation of the "export price" because the difference between that and the "normal value" of the product would be the "Dumping Margin" if the "normal value" exceeds the "export price".

[6] The relevant statute providing for this imposition of Anti-Dumping Duties is the Countervailing and Anti-Dumping Duties Act 1993 ("the Act") and the Regulations made thereunder and our international commitments under the WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement ("AD Agreement"). The remedy in the form of duties imposed would level the competition and disincentivise the exporter from trying to injure the domestic market of any importing country with respect to the same or comparable merchandise.

Decision Of The Finance Minister

[7] Before the Finance Minister publishes in the gazette the relevant Order for the imposition of the Anti-Dumping Duties on specific merchandise for a specific period of time, there is first an investigation to be undertaken by the Investigating Authority ("IA") under the Act which may investigate pursuant to a complaint by the local producers in the importing country and in this case, Malaysia.

[8] This elaborate process may involve the hauling and trawling of hundreds of thousands of trade entries in the records kept by the exporter to Malaysia as well as the answering of the questionnaires furnished by the IA. The findings of the IA are published in the form of a Preliminary Determination before a Final Determination on dumping and injury is made.

[9] As the calculation of the "export price" requires the taking into consideration of various cost factors and making it comparable where trade and ex-price from the factory is concerned, the IA is obliged to disclose the data, information and calculations it had used for arriving at its Dumping Margin calculation so that the Anti-Dumping ("AD") Duties may be verified by the party on whom it is imposed. Section 18(8) of the Act provides that the Government shall indicate to the parties in question the information that is necessary to ensure a fair comparison.

[10] A few parties are involved on the various stages of determining the AD Duties as provided for in s 30 of the Act. A complaint in the form of a petition is presented to the Minister of International Trade and Industry (MITI") under s 30(1) of the Act. The MITI appoints authorized persons or officers in writing to carry out the necessary investigation under the IA under s 30(2) of the Act. The 5th respondent MSA was the party that filed an AD Petition to the MITI on behalf of Malaysia Steel Works (KL) Bhd, Amsteel Mills Sdn Bhd and Antara Steel Mills Sdn Bhd for the initiation of an AD investigation on the imports of the Rebar originating or exported from Singapore and Turkey.

[11] Under s 30(3) of the Act any finding of an investigation, whether for the purpose of a Preliminary or Final determination, or a review, shall be forwarded to the MITI. The said Minister shall make a recommendation to the Minister of Finance ("MOF") who shall make a determination or decision under s 30(4). It is the Government of Malaysia that makes a final determination under s 25 as to whether there is a Dumping Margin and if so the AD Duties to be imposed. The AD Duties were imposed by the MOF signing the Customs (Anti-Dumping Duties) Order 2020 [P.U.(A) 22 dated 21 January 2020] ("MOF Decision"). The collection of the AD Duties imposed under the Act shall be by an officer of custom under the Customs Act 1967 as provided for in s 30(5).

[12] Under s 34A(1) of the Act an interested party who is not satisfied or who is aggrieved by the decision of the Government in relation to a Final Determination or a Final Administrative Review Determination under the Act shall have the right to refer such matter to the High Court for judicial review under the Rules of Court 2012.

[13] In this judicial review, all the relevant parties had been made respondents, ie the Minister of Finance as the 1st respondent, the MITI as the 2nd respondent, the Director General of the Royal Malaysian Customs as the 3rd respondent and the Government of Malaysia ("GOM") as the 4th respondent. The first to the 4th respondents shall be collectively referred to as "the respondents" and the complainant, Malaysia Steel Association, as the 5th respondent.

[14] The IA had used the internal sale price between the producer Diler Demir Celik Endustru Ve Ticaret AS ("DDC") in Turkey and its related company which is its wholly-owned subsidiary, Diler Dis Ticaret Anomin Sirketi ("DDT"), as the "export price" of the merchandise. DDC is the applicant in the High Court below and the appellant before us. The respondents and the 5th respondent are the respondents before us in this appeal from the High Court.

Before The High Court

[15] The judicial review application under O 53 r 3(1) of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC") was for a certiorari order to quash the following:

(i) The MOF's decision to impose AD Duties at the rate of 3.62% on Steel Concrete Reinforcing Bar Products originating or exported from the applicant in the Republic of Turkey from 22 January 2020 to 21 January 2025 as set out in the Customs (Anti-Dumping Duties) Order 2020 [P.U.(A) 22 dated 21 January 2020] (the "1st impugned Decision"); and

(ii) The MITI's decision and/or recommendation to impose AD Duties at the rate of 3.62% on Steel Concrete Reinforcing Bar Products originating or exported from the applicant in the Republic of Turkey as set out in the Notice of Affirmative Final Determination [P.U.(B) 46 dated 21 January 2020] and the Final Determination Report of an Anti-Dumping Duty Investigation dated 7 January 2020 respectively (the "2nd impugned Decision") (collectively called the "Impugned Decisions").

[16] At the judicial review hearing before the High Court, the determination of the "export price" was challenged by the applicant DDC as being wrong as DDC and DDT are related companies and the selling price is unreliable under s 17(2) of the Act read with s 2(5) of the Act.

[17] The AD Duties imposed was at the rate of 3.62% on the Rebar, the subject merchandise imposed from 22 January 2020 to 21 January 2025 following an AD Duties Investigation with regard to the imports of the subject merchandise originating or exported from the Republic of Singapore and the Republic of Turkey. The IA also did not see it fit to furnish, when requested by the applicant, the details of the calculation to arrive at the Dumping Margin and this the applicant said is a breach of the Act rendering its determination of the AD Duties to be illegal and irrational as it could not then be independently verified. Such a determination, it was argued by the applicant, was also made in breach of natural justice and so ought to be set aside.

[18] It was also argued by the applicant that the determination of dumping, even if it be true, is not actionable to AD Duties being imposed as there was no evidence showing material injury to the domestic market for the same merchandise and much less a causal link between the dumping of the merchandise and the injury caused to the domestic industry for the Rebar.

[19] The High Court rejected the applicant's argument that to take the internal sale price between DDC and DDT is an error of law and instead preferred the sum objectively determined from the sale invoices issued by DDC to DDT to determine the "export price". This is in spite of the clear provision of s 17(2) of the Act, where if the price is not reliable in the case of the sale to a related party within the meaning of s 2(5) of the Act as in this case, then the price at which the merchandise is first sold to the first independent buyer is to be taken for the purpose of calculating backwards the "export price."

[20] The High Court further held that there was no breach of natural justice as sufficient details and particulars for the purpose of the applicant's verification of the AD Duties had been furnished in the circumstances of the case and that a causal link has been shown between the dumping and the material injury to the domestic market of the subject merchandise.

[21] The High Court did not appear to have considered the ground of complaint of the applicant DDC on the need to make proper adjustments to the duty drawback granted by the Turkish authorities for its Rebar export sales by adding the value of the duty drawback when calculating the Dumping Margin when both art 2.4 of the WTO AD Agreement and s 18 of the Act provide for it.

In the Court of Appeal

[22] The main grounds before the Court of Appeal were as follows:

(i) That the "export price" used for determining the Dumping Margin was wrong in law as it cannot in the circumstances of the case be the price of the internal sale from DDC to DDT in Turkey before the subject merchandise entered the commerce of Malaysia in breach of art 2.1 of the WTO AD Agreement;

(ii) That the "export price" needs to be constructed in this case as the "export price" from DDC to DDT is unreliable being a sale between related parties and so the first sale to an independent buyer in Malaysia ought to be taken as the sale price from which the "export price" is to be constructed under s 17(2) of the Act and arts 2.3 and 2.4 of the WTO AD Agreement;

(iii) That for the purpose of a fair comparison between the constructed "export price" and the "normal value" at the same level of trade at the ex-factory level, there was a failure inter alia to make adjustment for duty drawback under s 18 of the Act resulting in a wrong Dumping Margin;

(iv) That the IA must disclose upon request the reasons for rejecting the data and information supplied by the applicant and must give details it took into account and documents relied on for constructing the "export price" for the applicant DDC to be able to verify the calculation of the Dumping Margin as required under arts 6 and 12 of the WTO AD Agreement and ss 18(8) and 38(4) of the Act;

(v) That the Final Determination arrived at by the respondents in breach of the legal obligations to provide reasons and to disclose its calculation of the Dumping Margin is in breach of the Act and the WTO AD Agreement and also of natural justice;

(vi) That there is no proof of Dumping from the calculation of the respondents as the wrong data and information had been used to construct the "export price" to show that it was below the "normal value" of the domestic sale in the exporting country;

(vii) That in any event there is no material injury to the domestic market in Malaysia of the subject merchandise and much less a causal link between the dumping and alleged material injury for the imposition of the Anti-Dumping Duties.

Whether The "Export Price" Used For Determining The Dumping Margin Was Wrong In Law As It Cannot In The Circumstances Of The Case Be The Price Of The Internal Sale From DDC To DDT In Turkey Before The Subject Merchandise Entered The Commerce Of Malaysia

[23] DDC did an internal sale of the subject merchandise in Turkey to its wholly-owned subsidiary DDT, also based in Turkey. In that sense there is no export out of Turkey as yet. From there DDT then exported the subject merchandise to Malaysian importers. The question then is how is the "export price" to be determined for after all to arrive at the "Dumping Margin" one needs to know by how much the "normal value" of a merchandise exceeds the "export price".

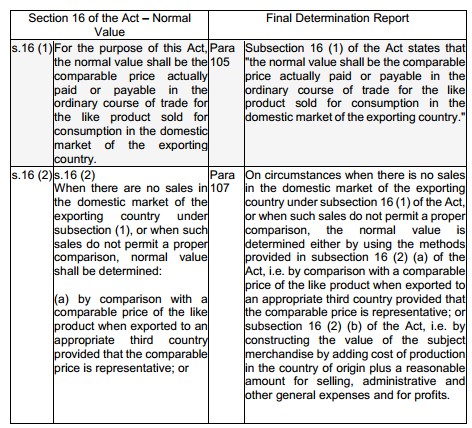

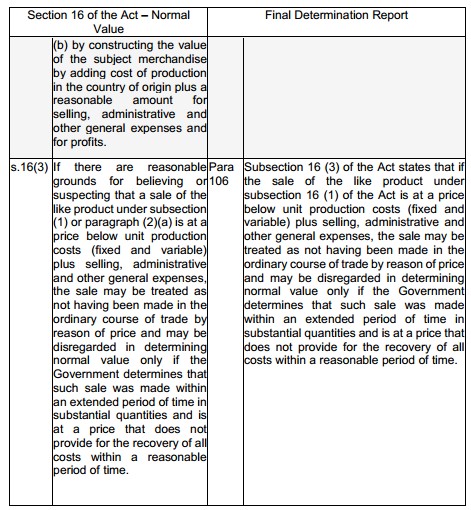

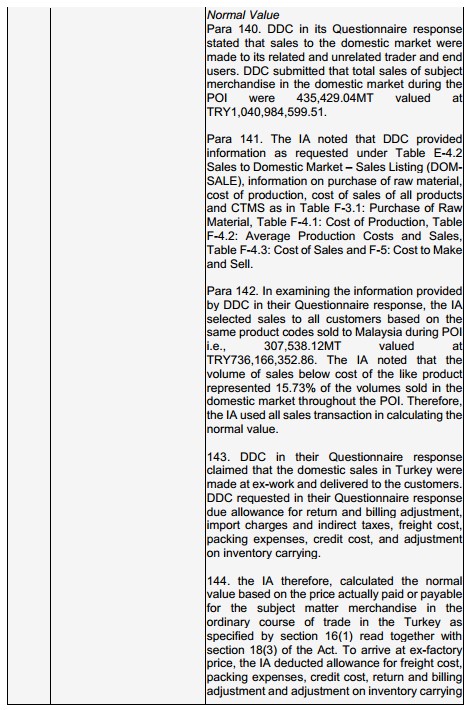

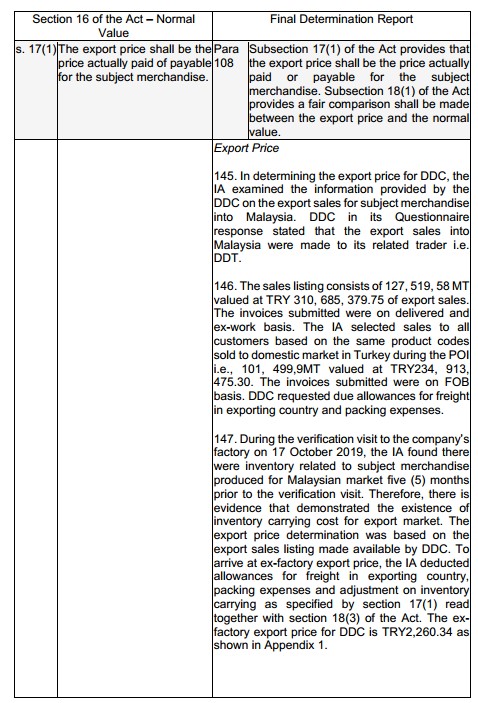

[24] The determination of the "normal value" of the merchandise in the exporting country in Turkey is determined under s 16(1) of the Act as the comparable price actually paid or payable in the ordinary course of trade for the like product sold for consumption in the domestic market of the exporting country.

[25] As for the "export price" the learned FC for the respondents submitted that it should be the price at which the merchandise is sold by DDC to DDT based on s 17(1) where the "export price" "shall be the price actually paid or payable for the subject merchandise". The High Court agreed with this interpretation of the respondents as the price is easily and objectively determined from the relevant invoices for the relevant period or transactions.

[26] The problem with that interpretation is that there is no export of the subject merchandise to an importer in Malaysia yet for the merchandise was still within Turkey and had not left the exporting country. The mischief of the Act is against dumping of merchandise in Malaysia at an "export price" lower than the "normal value" of the merchandise in the country of its origin. As the goods had not left the country of origin yet, it would be rather artificial to take the "export price" to be the price at which DDC sold the merchandise to DDT as the Act had not been triggered, there being no dumping yet.

[27] The Black's Law Dictionary 11th edn, Editor-in-chief Bryan A. Garner JD, LLD, tells us what is obvious by the meaning of the verb "export". It is "to send, to take, or carry (a good or commodity) out of the country; to transport (merchandise) from one country to another in the course of trade." The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines the noun "export" as "a commodity conveyed from one country or region to another for purposes of trade."

[28] It would be a tremendous strain on the word "export" to say that one is exporting a merchandise from one country to another company within the same country. The verb "export" has always to do with the merchandise leaving the country from which it is exported to an importer in another country. In fact, it is almost impossible to use the verb "export" without using it to convey where the thing is "exported from or to" and that transaction involves the thing leaving the country of origin.

[29] Looking at the way the word "export" is used in the Act, there is no export and hence no "export price" when a merchandise is sold by one company to another company within the same country of origin. The expression "not exported directly to Malaysia" in s 18(5) further reinforces the fact that the Act deals with the subject merchandise being exported from another country to Malaysia, whether directly or indirectly.

[30] The Act differentiates between "exporting country", "country of origin", "intermediate country" or "third country" and "Malaysia". Section 16(2)(a) uses the expression "by comparison with a comparable price of the like product when exported to an appropriate third country provided that the comparable price is representative." In s 18(5) reference is made to "sold from exporting country to Malaysia" as follows:

"(5) In a case where the subject merchandise is not imported directly from the country of origin but is exported from an intermediate country, the price at which the subject merchandise is sold from the exporting country to Malaysia shall be compared with the comparable price in the exporting country."

[Emphasis Added]

[31] Section 44 on "Transhipment" referred to "country of origin", "intermediate country" and "Malaysia" together as follows:

"44. Transhipment

In cases where merchandise is not imported into Malaysia directly from the country of origin, but is exported to Malaysia from an intermediate country, the provisions of the Act shall be fully applicable and the transaction, for the purposes of this Act, shall be regarded as having taken place between the country of origin and Malaysia."

[Emphasis Added]

[32] With the greatest of respect, the High Court does not have the luxury and liberty to interpret s 17(1) of the Act without regard to the legal framework set in place for anti-dumping which is premised on the fact that there must first be an "export" without which there can be no "export price" in a case where there is no dumping of the subject merchandise in Malaysia yet. We are afraid we cannot associate with her reasoning in para [51] of her grounds of judgment ("GOJ") where she reasoned as follows:

"[51].....Apparently, the IA had acted pursuant to subsection 17(1) of Act 504 which provides that the export price shall be the price actually paid or payable for the subject merchandise. There were invoices as proof of sales transaction between the Applicant and DDT obtained by the IA from the Applicant and as such the IA reliance on those sales transactions to be the basis of the export price cannot be said to be unreliable."

[Emphasis Added]

[33] There is no good reason why a manufacturer in its country of origin cannot harness the corporate law there to limit and manage risk and costs by establishing a wholly-owned subsidiary for purpose of its export ventures overseas. The use of trade intermediaries or agents is not uncommon whether it be for tax advantages from transfer pricing or otherwise or to qualify for incentives or to manage risks.

[34] That said, being related companies there is also the danger of price suppression for sale to related company in the exporting country or price inflation in the case of export price to a related company in the importing country. Whilst the price between related companies like that between a parent company and its wholly-owned subsidiary may not be reliable or even realistic, what is important is the "export price" which an independent buyer in the importing country Malaysia would be prepared to pay for that is the materially relevant price for determining if there is dumping from the Dumping Margin calculation.

[35] The Act defines "dumping" to mean "the importation of merchandise into Malaysia at less than its normal value as sold in the domestic market of the exporting country and "Dumping Margin" as "the amount by which the normal value of a merchandise exceeds the export price."

[36] The definitions are a follow-through of Malaysia's commitment to the WTO AD Agreement where art 2.1 provides as follows:

"2.1 For the purpose of this Agreement, a product is to be considered as being dumped, ie introduced into the commerce of another country at less than its normal value, if the export price of the product exported from one country to another is less than the comparable price, in the ordinary course of trade, for the like product when destined for consumption in the exporting country."

[Emphasis Added]

[37] It is only after the merchandise has been "introduced into the commerce of another country" at less than its "normal value", that there is dumping. In the present discussion the merchandise must be introduced into Malaysia. For so long as the merchandise remains in Turkey, in an internal trade, there is no dumping into Malaysia.

[38] Another justification for the High Court below preferring to use the objective test of determining the "export price" by using the sale price stated in the invoice between DDC and DDT was by relying on a decision of the WTO Appellate Body in the case of United States - Anti-Dumping Measures on Certain Hot Rolled Steel Products From Japan, WT/DS184/AB/R. However, that case was referring to the determination of "normal value" which is the requirement under s 16 of our Act and not on the determination of the "export price" under s 17 of the Act. The High Court below said as follows:

"[56] This has been expressly acknowledged by the Appeal Board in the case of United States - Anti-Dumping Measures On Certain Hot-Rolled Steel Products From Japan WT/DS184/AB/R where it was held:

"166. The text of art 2.1 is, however, silent as to who the parties to relevant sales transactions should be. Thus, art 2.1 does not expressly mandate that the sale be made by the exporter for whom a margin of dumping is being calculated. Nor does art 2.1 expressly preclude that relevant sales transactions might be made downstream, between affiliates of the exporter and independent buyers. In our view, provided that all of the explicit conditions in art 2.1 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement are satisfied, the identity of the seller of the "like product" is not a ground for precluding the use of a downstream sales transaction when calculating normal value. In short, we see no reason to read into art 2.1 an additional condition that is not expressed."

[Emphasis Added]

[39] This becomes more obvious when one refers to para 171 of the same decision in United States - Anti-Dumping Measures on Certain Hot Rolled Steel Products From Japan, WT/DS184/AB/R as follows:

"171. Nor is our reading of art 2.1 altered by the fact that art 2.3 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement provides expressly for the use of downstream sales in constructing export price, when "the export price is unreliable because of association". We are concerned with the text of art 2.1 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement and, irrespective of the terms of art 2.3, we are satisfied that art 2.1 does not preclude the use of downstream sales "in the ordinary course of trade" in calculating normal value."

[Emphasis Added]

[40] The learned authors Philippe De Baere, Clotilde du Parc and Isabelle Van Damme in The WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement - A Detailed Commentary, Cambridge University Press, 2021 opined at pp 55-56 as follows:

"126. Sales transactions must satisfy four conditions to be used for calculating normal value. Those conditions are (i) the sale must be in the ordinary course of trade; (ii) the sale must be of the like product; (iii) the product must be destined for consumption in the exporting country; and (iv) the price must be comparable.

127. The fact that only four conditions for the sales transaction are expressed in art 2.1 has been understood to mean that there is 'no reason to read into art 2.1 an additional condition that is not expressed'. In US - Hot-Rolled Steel, the Appellate Body explained that this means that there is no separate condition in art 2.1 regarding the identity of the seller of the like product. Thus, 'the identity of the seller of the like "product" is not a ground for precluding the use of a downstream sales transaction when calculating normal value. Nor does art 2.1 preclude the use of downstream sales in the ordinary course of trade in calculating normal value."

[Emphasis Added]

[41] The objective price in the invoices between DDC and DDT is not the point because it is unreliable as being transactions between related parties and it does not capture the "export price" at the point of first resale of the merchandise to an independent buyer in the buyers from Malaysia.

[42] After all, one is not dealing with what is called a "Standard Situation" where a comparison is made directly between the "export price" being the transacted price at which the merchandise is sold by a producer/exporter in the exporting country to an importer in the importing country. The Standard Situation, as referred to by The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development ("UNCTAD") in its publication Dispute Settlement - World Trade Organization 3.5 Anti-dumping Measures, New York and Geneva, 2003 at p 8 is illustrated as follows:

"Article 2.1 provides that a product is dumped if the export price of the product exported from one country to another is less than the comparable price, in the ordinary course of trade, for the like product when destined for consumption in the exporting country. This is the standard situation: the normal value is the price of the like product, in the ordinary course of trade, in the home market of the exporting Member.

This definition presupposes that there are in fact domestic sales of the like product and that such sales are made in the ordinary course of trade. In this context, it is important to remember that, in the first stage, comparisons are made between identical or closely resembling models and that only later one weighted average dumping margin is calculated per producer/exporter. Thus, in the first stage, each exported model is matched to a domestic model, where possible, in order to determine whether a domestic price in the ordinary course of trade exists.

If this is found to be the case and if, for example, the domestic price of a model is 100 and its export price is 80, the dumping amount is 20 and the dumping margin is 20/80x100=25%."

[Emphasis Added]

[43] The High Court, with respect, erred in affirming the decision of the respondents to take the internal sale price between the producer and its wholly-owned subsidiary as the "export price" when the same would not comport with the rationale of dumping and when to do so would be against the requirement of the Act. The final decision arrived at in AD Duties imposed was thus an error of law rendering the decision illegal and irrational for breach of art 2.1 of the WTO AD Agreement which is the international law on trade that Malaysia has agreed to be bound by.

Whether The Export Price From DDC To DDT Is Unreliable Being A Sale Between Related Parties And So The First Sale To An Independent Buyer In Malaysia Ought To Be Taken As The Sale Price From Which The "Export Price" Is To Be Constructed Under Section 17(2) Of The Act And Arts 2.3 And 2.4 Of The WTO AD Agreement

[44] The "export price" cannot be the price at which DDC sold to DDT, not only because there was no "introduction into the commerce of another country", Malaysia, and correspondingly no dumping in Malaysia but also because that price is unreliable. Internal sale in the country of origin to a trade intermediary, whether related to the producer or governed by a compensatory agreement, has a way of distorting the "export price". Section 17(2) of the Act s designed to address that anomaly. Where the "export price" is unreliable either because of the control mechanism in a related-party transaction or via a compensatory agreement then the "export price" has to be "constructed".

[45] Section 17(1) and (2) of the Act read as follows:

"(1) The export price shall be the price actually paid or payable for the subject merchandise.

(2) In cases where there is no export price or where it appears that the export price is unreliable because the exporter and the importer or a third party are related, or that there is a compensatory arrangement between the exporter and the importer or a third party, the export price may be constructed on the basis of the price at which the subject merchandise is first resold to an independent buyer, or if the subject merchandise is not resold to an independent buyer, or not resold in the condition imported, on any reasonable basis."

[Emphasis Added]

[46] We do not think that anyone can seriously dispute that a parent company DDC of its wholly-owned subsidiary DDT would virtually and directly control DDT as it is DDC that decides on who would be its directors sitting in the board of DDT. The requirements of s 2(5) and (6) of the Act have been met as highlighted below:

"(5) Parties shall be deemed to be related if:

(a) one of them directly or indirectly controls the other;

(b) both of them are directly or indirectly controlled by a third party; or

(c) together they directly or indirectly control a third party: Provided that there are grounds for believing or suspecting that the effect of the relationship is such as to cause the party concerned to behave differently from non-related parties.

(6) One party shall be deemed to control another when the first- mentioned party is legally or operationally in a position to exercise restraint or direction over the latter."

[Emphasis Added]

[47] The rationale for using the price at which the subject merchandise is first resold to an independent buyer is not difficult to find. It is to get at the real price at an arm's length transaction unaffected by related relationship of control or other extraneous considerations. It is a reaffirmation of the basic premise set out in s 17(1) which reads:

"(1) The export price shall be the price actually paid or payable for the subject merchandise."

[Emphasis Added]

[48] The word "actually" is used circumspectly and purposefully to address situations where the "export price" is not the reliable price because of intervening levels of sale from the producer to the first resale to an independent Malaysian buyer, whether the intermediaries are in the exporting country or the importing country. In the instant case we are not derogating from the proposition set out in s 17(1) of the Act but rather affirming it.

[49] Where there is only one level of sale ex-factory from the producer in the exporting country to the importer in the importing country, then there is no problem of using the "export price" being the price of resale for in such a circumstance there is an arm's length transaction with no difficulty in determining the "export price." The payment by the Malaysian importers happened to be the first independent buyer that the subject merchandise was first resold to from Turkey after passing through one level of internal sale in the exporting country.

[50] Implied in s 17(2) is the fact that what is relevant is what the independent importer in the importing country, and in this case Malaysia, paid for the subject merchandise as that would be the genuine base from which one may work backwards to find the "export price" in an arm's length transaction for the purpose of a fair comparison under s 18(1) without which there can be no fair and reasonable determination of the Dumping Margin, if any.

[51] We appreciate that the word used is "may" in s 17(2)"..... the export price may be constructed on the basis of the price at which the subject merchandise is first resold to an independent buyer,." as indicating it is not mandatory or obligatory but only discretionary or optional. The word "may" is not an authoritarian word but a word conferring authority. All that it means is that the IA is of course at liberty to be generous and use the stated price of first resale to an independent buyer in Malaysia for that may yield a greater margin in favour of no dumping but Governments are constrained to protect its own domestic industry and so would try to arrive at a constructed "export price" which when fairly compared with the "normal value" would be more accurate in showing dumping if the "normal value" exceeds the lower constructed "export price."

[52] The word "may" in s 17(2) of the Act does not mean that the IA may proceed on any sale price even for internal sale in the exporting country on ground that such an "export price" is easily and objectively ascertained as that price is unreliable as it is given to manipulation and massaging or even just a manner of managing export risks if parties are related or it may be more under a compensatory agreement with a trade intermediary or third party.

[53] The conditions set for the application of a constructed "export price" under s 17(2) of the Act is the statutory embodiment of art 2.3 of the WTO AD Agreement and once again the learned authors Philippe De Baere, Clotilde du Parc and Isabelle Van Damme in The WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement - A Detailed Commentary Cambridge University Press, 2021 at p 98 addressed the use of "may" in art 2.3 corresponding to our s 17(2) of the Act as follows:

"264. The use of the term 'may' in art 2.3 suggests that even if the conditions of art 2.3 are met, there is no obligation for investigating authorities to construct the export price. It is clear, however, that the conditions laid down in art 2.3 must be fulfilled in order to construct the export price. Construction of the export price in other circumstances is not envisaged."

[54] Section 17(1) of the Act remains true as a general proposition of law and in a case where the "export price" sought to be used is unreliable, then resort must be had to s 17(2) where the relevant starting point price is the price at which the subject merchandise is sold to an independent buyer which is the price paid or payable by the Malaysian importer.

[55] Our s 17(2) of the Act seeks to incorporate art 2.3 of the WTO AntiDumping Agreement to which Malaysia is a party and it reads:

"In cases where there is no export price or where it appears to the authorities concerned that the export price is unreliable because of association or a compensatory arrangement between the exporter and the importer or a third party, the export price may be constructed on the basis of the price at which the imported products are first resold to an independent buyer, or if the products are not resold to an independent buyer, or not resold in the condition as imported, on such reasonable basis as the authorities may determine."

[Emphasis Added]

[56] Section 17(2) was designed to address the anomaly when an original exporter like in DDC's case, uses a trade intermediary for its export and in this case its wholly-owned subsidiary DDT for its export to Malaysian importers. It was precisely because the export price if determined from what DDC invoiced DDT would not be reasonable and indeed unreliable that s 17(2) was incorporated in keeping with our WTO's commitments under the AD Agreement.

[57] Edwin Vermulst in his book titled Oxford Commentaries on the GATT/ WTO Agreements - The WTO Anti-Dumping Agreement - A Commentary at pp 14 and 15 illustrated as follows:

"Article 2.1 merely provides indirectly that the export price is the product exported from one country (the exporting country) to another (the importing country). If, for example, producer x in country X sells T- shirts to importer y in country Y, then the price charged by producer x to importer y is the export price.

It may happen that foreign producer sell the product under consideration to other parties, typically traders, in the exporting country which will then resell it to the importing country. On the basis of art 2.1, it seems clear that the export price then is the price charged by the trader to the importer....."

[Emphasis Added]

[58] The initial error of High Court was inadvertently perpetuated in para [52] of its GOJ when it reasoned as follows:

"[52] The use of the selling price from the Applicant to DDT by the IA to establish the export price is reasonable and valid even though the Applicant and DDT are related trading companies as the IA in determining the export price had acted in accordance with s 17(1) of Act 504 and there is no requirement for the export price to be constructed in accordance to s 17(2) read together with s 17(3) of Act 504 (by using the price at which the subject merchandise is first resold to an independent buyer (DDT to the Malaysian Importer and for allowance to be made for all costs incurred between importation and resale) as the issue of unreliability of export price does not arise."

[Emphasis Added]

[59] A similar issue had come before the High Court in BX Steel Posco Cold Rolled Sheet Co Ltd v. Minister Of Finance & Ors; FIW Steel Sdn Bhd (Intervener) [2020] MLRHU 548 ("BX Steel Posco") where the High Court Judge Nordin Hassan J (now FCJ) opined as follows:

"[20] The next ground raised by the applicant is with regards to the noncompliance of s 17 of the CADD 1993 by the first to 4th respondents.

[21] The applicant submitted that the first to 4th respondents acted in excess of their jurisdiction in failing to use the price based. Instead the respondent used a 'lower export price' and as such artificially inflating the dumping margin.

[22] On this issue, s 17 of the CADD 1993 provides as follows:

.....

[23] The provision of s 17(1) is plain and unambiguous that the export price is the price actually paid for the subject merchandise which is the price paid by the importer. In the present case the Malaysian importer.

.....

[27] In furtherance to this, it is also undisputed fact that there is a compensatory agreement between the applicant and Benxi Hong Kong, the trader. The applicant exported its product to Malaysia through Benxi Hong Kong and commission has been paid by the applicant. All this information was submitted to the lA in the applicant questionnaire response and verified by IA.

[28] In this regard, by virtue of s 17(2) of the CADD 1993, the export price must be based on the price actually paid by the Malaysian importers."

[60] We appreciate that the High Court case of BX Steel Posco (supra) is not binding on another High Court, as they are Courts of coordinate jurisdiction. Be that as it may, generally one would have expected any divergence from an earlier decision to have been distinguished so that an appellate court would be better able to appreciate the reasons for the rejection of a previous decision, paving the way for an orderly development of the law where certainty and new challenges to the law are concerned.

[61] We agreed with learned counsel for the appellant that the decision of the High Court in BX Steel Posco (supra) is binding on the executives and its agents, in this case the respondents. It goes without saying that the Court's decision is binding on the Executive branch of the Government as was reiterated in Metacorp Development v. Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri [2011] 10 MLRH 854 at para 24, by Justice Rohana Yusuf J (later PCA) as follows:

"Thus, the failure of the Respondent to follow the decision of the Superior Courts in Penang Realty as well as Lower Perak renders its decision defective. These two cases are binding authorities on the Respondent, being an arm of the executive. Also based on doctrine of stare decisis this Court is also bound by the decisions of the superior court. Since the Respondent's decision is not based on the legal authorities of the Superior Courts such decision is in excess of its authority."

[Emphasis Added]

[62] As the Malaysian importer is an independent buyer, there is no suggestion of price fixing or price fiddling. Whether the exporter sells at a profit or at a loss for reasons such as to injure or kill the domestic market of Malaysia or to gain market share in Malaysia, the "selling price" to the independent buyer is the base from which one starts working backwards to come to a constructed "export price."

[63] Only then can there be "a fair comparison made between the "export price" and the "normal value" as required under s 18(1) of the Act. The learned High Court Judge appeared to have misconstrued this need to work backwards from an arm's length selling price when the first resale was made to an independent buyer in Malaysia when she expressed her concerns if she did not take the price at which DDC sold to DDT as the "export price" at paras 61 and 62 of her GOJ as follows:

".....should the IA use the price from DDT to Malaysian importers as the export price, the IA will not be able to arrive at the accurate ex-factory export price as there were sales transactions between the Applicant to DDT (at a different level of trade) before the product was sold by DDT"

[64] Her concerns had been addressed by s 17(3) of the Act that provides as follows:

"(3) If the export price is constructed as described in subsection (2), allowance shall be made for all costs incurred between importation and resale."

[65] As selling for international export through a trade intermediary is not uncommon in international trade, this need to construct the "export price" from the selling price charged to the first independent buyer had been addressed in the WTO Panel Report - European Union Anti-Dumping Measures on Biodiesel from Indonesia WT/DS480/R ("EU-Biodiesel") at paras 7.112 - 7.114 as follows:

"(a) "the price charged to the first independent buyer is a starting-point for the construction of an export price";

(b) "A member may thereafter make any adjustments for allowances to the extent permitted under the fourth sentence of art 2.4 of the AntiDumping Agreement"; and

(c) "this does not change the fact that a Member must begin with the price charged to the first independent buyer".

7.112. Article 2.3 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement authorizes a Member to construct the export price where, inter alia, the actual export price is unreliable because of association between the exporter and importer. The plain language of art 2.3 makes clear that "the price charged to the first independent buyer is a starting-point for the construction of an export price". Article 2.3 does not itself contain any guidance regarding the methodology to be employed in order to construct the export price. The only rules governing the methodology for construction of an export price are set forth in art 2.4, which provides that

"[i] In the cases referred to in para 3, allowances for costs, including duties and taxes, incurred between importation and resale, and for profits accruing, should also be made". The panel in US - Stainless Steel (Korea) found that this sentence authorizes the only allowances that can be made. After determining the price charged to the first independent buyer, an investigating authority would then work "backwards from the price at which the imported products are first resold to an independent buyer".

7.113. There is no dispute that customers purchasing the biodiesel from P.T. Musim Mas' related importer [[***]] are the first independent buyers. The sole issue is whether the premium that the customer pays to P.T. Musim Mas' related importer [[***]] is properly considered as part of the price that is charged to first independent buyers.

7.114. There is no prior guidance on the interpretation of the term "price" as it appears in the phrase "the price at which the imported products are first resold to an independent buyer" in art 2.3 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines the term "price" as "the sum in money or goods for which a thing is or may be bought or sold, or a thing or person ransomed or redeemed". This would suggest that the phrase "the price at which the imported products are first resold to an independent buyer" refers to the sum in money for which the imported product was bought or sold. There is no further guidance regarding the term "price". In our view, as discussed in US - Stainless Steel (Korea), the language "first resold" relates to the price being the starting point for the construction of the export price, from which an investigating authority would work "backwards" to construct an export price that would have been paid by the related importer had the sale been made on a commercial basis. Accordingly, in constructing the export price, we consider that a Member must begin by determining the sum in money for which the imported product was bought by or sold to an independent buyer. A Member may thereafter make any adjustments for allowances to the extent permitted under the fourth sentence of art 2.4 of the Anti-Dumping Agreement. However, this does not change the fact that a Member must begin with the price charged to the first independent buyer.

[Emphasis Added]

[66] We find that the constructed "export price" that is to be determined for the purpose of imposing the AD Duties should be following the formula as set out in s 17 of the Act being the transacted price as the starting point under s 17(2) of the subject merchandise when first resold to an independent buyer and allowance as in a working backwards shall be made "for all costs incurred between importation and resale" under s 17(3). This is the statutory enactment of our commitment under art 2.4 of the WTO ADA with its fourth sentence highlighted as follows:

"2.4 A fair comparison shall be made between the export price and the normal value. This comparison shall be made at the same level of trade, normally at the ex-factory level, and in respect of sales made at as nearly as possible the same time. Due allowance shall be made in each case, on its merits, for differences which affect price comparability, including differences in conditions and terms of sale, taxation, levels of trade, quantities, physical characteristics, and any other differences which are also demonstrated to affect price comparability. In the cases referred to in para 3, allowances for costs, including duties and taxes, incurred between importation and resale, and for profits accruing, should also be made. If in these cases price comparability has been affected, the authorities shall establish the normal value at a level of trade equivalent to the level of trade of the constructed export price, or shall make due allowance as warranted under this paragraph. The authorities shall indicate to the parties in question what information is necessary to ensure a fair comparison and shall not impose an unreasonable burden of proof on those parties."

[Emphasis Added]

[67] The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development ("UNCTAD") in its publication Dispute Settlement - World Trade Organization 3.5 AntiDumping Measures, New York and Geneva, 2003 has this helpful explanation at p 8 as follows:

"Article 2.3 ADA provides that the export price then may be constructed on the basis of the price at which the imported products are first resold to an independent buyer. In such cases, allowances for costs, duties and taxes, incurred between importation and resale, and for profits accruing, should be made in accordance with art 2.4 ADA. Such allowances decrease the export price, increasing the likelihood of a dumping finding.

This was an important reason for a WTO Panel to interpret the relevant part of art 2.4 restrictively."

[Emphasis Added]

[68] Reference was then made to the Panel Report, United States - AntiDumping Measures on Stainless Steel Plate in Coils and Stainless Steel Sheet and Strip from Korea (US - Stainless Steel), WT/DS179/R, paras 6.93-6.94 as follows:

"The term "should" in its ordinary meaning generally is non-mandatory, ie, its use in this sentence indicates that a Member is not required to make allowance for costs and profits when constructing an export price. We believe that, because the failure to make allowance for costs and profits could only result in a higher export price — and thus a lower dumping margin — the AD Agreement merely permits, but does not require, that such allowances be made.

.....we view this sentence as providing an authorization to make certain specific allowances. We therefore consider that allowances not within the scope of that authorization cannot be made."

[Emphasis Added]

[69] Clearly by using the price at which the subject merchandise was sold by DDC its producer to its related company DDT as the "export price" instead of the price at which it was resold to the first independent buyer in the importing country, the IA had begun on the wrong footing and committed an error of law. Having started wrongly, the correct constructed "export price" cannot be arrived at for the simple reason that one cannot start off wrongly and yet arrive correctly.

[70] The use of "internal pricing" between DDC the producer and its related company DDT is illegal as it is not in accordance with statutorily prescribed provision in s 17(2) of the Act and the provisions in arts 2.3 and 2.4 of the WTO AD Agreement to which Malaysia is a party and thus rendering the decision made in excess of jurisdiction and ultra vires the Act.

[71] Both our High Court's decision in BX Steel Posco (supra) and the WTO Appellate Body case of EU-Biodiesel (supra) together with WTO leading commentaries do not support the use of internal pricing between related parties in the exporting country to construct backwards the "export price".

[72] We are reminded of the dicta of Richard Malanjum CJSS (later CJ) in the Federal Court in Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop Of Kuala Lumpur v. Menteri Dalam Negeri & Ors [2014] 4 MLRA 205 as follows:

"[84] In our jurisprudence the current governing principle is that an 'inferior tribunal or other decision-making authority, whether exercising a quasijudicial function or purely an administrative function, has no jurisdiction to commit an error of law ..... If an inferior tribunal or other public decision-taker does make such an error, then he exceeds his jurisdiction.....

It is neither feasible nor desirable to attempt an exhaustive definition of what amounts to an error of law, for the categories of such an error are not closed. But it may be safely said that an error of law would be disclosed if the maker asks himself the wrong question or takes into account irrelevant considerations or omits to take into account relevant considerations (what may be conveniently termed an Anisminic error) or if he misconstrues the terms of any relevant statute, or misapplies or misstates a principle of the general law' (see Syarikat Kenderaan Melayu Kelantan Bhd v. Transport Workers Union [1995] 1 MLRA 268 at p 342 per Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as he then was); Hoh Kiang Ngan v. Mahkamah Perusahaan Malaysia & Anor [1995] 1 MELR 1; [1995] 2 MLRA 435 at p 390)."

[Emphasis Added]

[73] As the respondents had misconstrued the law housed in s 17(2) of the Act and had constructed the "export price" based on a wrong methodology contrary to that provision of the Act, an error of law had crept into the imposition of the AD Duties rendering it illegal and in excess of the jurisdiction of respondents under the Act and so must be quashed and the decision of the High Court set aside.

Whether For The Purpose Of A Fair Comparison Between The Constructed "Export Price" And The "Normal Value" At The Same Level Of Trade At The Ex-Factory Level, There Was A Failure Inter Alia To Make Due Allowance, In The Form Of Adjustments, Under Section 18(3) Of The Act Resulting In A Wrong Dumping Margin Adjustment By Adding The Duty Drawback To The Constructed "Export Price"

[74] In the High Court below one of the grounds of complaint of the applicant DDC was that there were no proper adjustments made to the duty drawback granted by the Turkish authorities for its Rebar export sales by adding the value of the duty drawback when calculating the Dumping Margin when both art 2.4 of the WTO AD Agreement and s 18 of the Act provide for it.

[75] We are also persuaded that the duty drawback should be allowed under s 18 of the Act as there is sufficient basis for the applicant to say that the import duties for raw materials was imposed on them with respect to the product sold in the domestic market. The learned High Court Judge seemed to have inadvertently missed out on addressing the applicant's submission in this ground of challenge in the judicial review application.

[76] As art 2.4 of the WTO AD Agreement had been set out above, we would only need to refer to that part that reads as follows in sentence 3 thereof:

"2.4..... Due allowance shall be made in each case, on its merits, for differences which affect price comparability, including differences in conditions and terms of sale,taxation, levels of trade, quantities, physical characteristics, and any other differences which are also demonstrated to affect price comparability."

[Emphasis Added]

[77] Section 18 of the Act on "Comparison of normal value and export price" is our statutory enactment encapsulating the factors to be considered and it provides as follows:

"(1) A fair comparison shall be made between the export price and the normal value.

(2) The comparison shall be made at the same level of trade, normally at ex-factory level, and in respect of sales made at as nearly as possible the same time and due account shall be taken of other differences that affect price comparability.

(3) Where the normal value and the export price as established are not on a comparable basis, due allowance, in the form of adjustments, shall be made in each case, on its merits, for differences in factors that are claimed, and demonstrated, to affect prices and price comparability.

(4) If the determination of the export price under subsection 17(2) affects price comparability, the Government shall establish the normal value at a level of trade equivalent to the level of trade of the constructed export price, or shall make due allowance as provided under this section.

.....

(7) Where an exporter or importer claims for an adjustment under subsection (3), it shall prove that its claim is justified.

(8) The Government shall indicate to the parties in question the information that is necessary to ensure a fair comparison."

[Emphasis Added]

[78] We are satisfied that DDC in its Questionnaire Response had clearly stated with documentary evidence that the exemption of import duties on raw materials which is the drawback were only available on the condition that the Rebar were exported through the Turkish Inward Processing Regime ("IPR"). Thus, DDC's domestic sales of the subject merchandise does not enjoy similar duty drawback. This information was duly verified by the IA. As such due adjustment must be made to take into consideration the duty drawback which the respondents refused to.

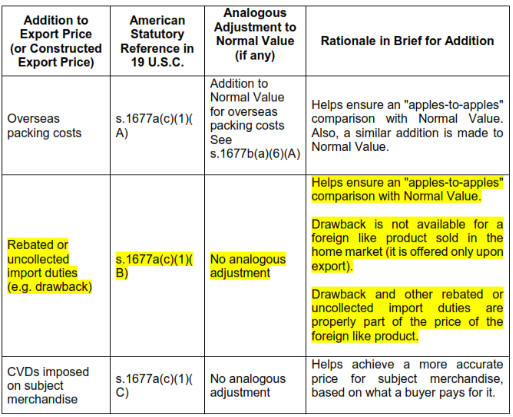

[79] Support for this proposition is found in a leading textbook Modern GATT Law, A Treatise on the Law and Political Economy of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and Other World Trade Organisation Agreements, Volume II, Second Edition in Two Volumes by Raj Bhala where the author set out the common adjustments that must be taken into account in an anti-dumping investigation, including the need to add duty drawback value to "export price" (because duty drawback is not available for the like product sold in the exporter's domestic market) as illustrated in the Table 66-2 below with the relevant parts highlighted:

[80] We agree that the necessity to add the duty drawback value to DDC's export price when making adjustment to calculate its Dumping Margin is to ensure that the duty drawback regime does not result in the finding of Dumping Margin because art VI.4 of GATT provides as follows:

"No product of the territory of any contracting party imported into the territory of any other contracting party shall be subject to anti-dumping or countervailing duty by reason of the exemption of such product from duties or taxes borne by the like product when destined for consumption in the country of origin or exportation, or by reason of the refund of such duties or taxes."

[Emphasis Added]

[81] We appreciate the argument of learned counsel for the applicant that whilst the IA acknowledged that "the duty drawback facility was granted due to export performance" it nevertheless did not see it proper and necessary to make due adjustment or allowance by adding the duty drawback value to the "export price" to allow for an "apples-to-apples" comparison to the "normal value".

[82] The IA had not seen it necessary to add the duty drawback though it appreciated that the same merchandise for domestic consumption in the country of origin does not enjoy such duty drawback. By misconstruing and not applying s 18 of the Act to arrive at a fair comparison between the constructed "export price" and the "normal value", an error of law had arisen and a wrong Dumping Margin had been arrived at. Therefore, the AD Duties imposed had to be quashed and set aside.

The Use Of The Sales Contract Dates Between DDT And Malaysian Importers

[83] The respondents had also rejected the Sales Contract dates between DDT and the Malaysian Importers for a fair comparison for the constructed "export price" and the "normal value" and instead had used the contract dates in the invoices between DDC and DDT even though the merchandise had not entered the commerce of Malaysia or imported into Malaysia.

[84] A fair comparison between the "export price" and the "normal value" should as far as possible be with respect to transactions during the same period. This Court had decided that the constructed "export price" is to be derived from the price paid by the Malaysian Importers to DDT, being the first independent sale after the merchandise had entered the commerce of Malaysia.

[85] The learned FC submitted that there were no sales in the domestic market of DDC if one were to take the dates of the Sales Contract between DDT and the Malaysian Importers. That would not be a reason then for abandoning the Sales Contract dates for the independent resale in preference of the dates of the Invoices between DDC and DDT in the internal sales. Rather one must then choose a period that most closely resembles the corresponding sales period between DDT and the Malaysian Importers.

[86] There is more than ample evidence that DDT entered into formal export sales contract with the Malaysian Importers where the key terms of parties, price and product (size, length, quantity) were all clearly spelt out in the Sales Contract exhibited. See the Court of Appeal case of Eng Song Aluminium Industries Sdn Bhd v. Keat Siong Property Sdn Bhd [2018] 6 MLRA 194.

[87] Taking the actual Sales Contract dates rather than the invoice's dates between DDC and DDT would more accurately reflect the Dumping Margin as invariably and ordinarily the sale price to the Malaysian exporter at arm's length would be higher than the price to a related party in an internal sale in the domestic market of the exporting country.

[88] The decision of the respondents in insisting to base their calculation of the "export price" on the invoice date of the sales between DDC and DDT which are internal sales within the exporting country and not on the date of the sales between DDT and the Malaysian Importers is irrational and wrong in law as there is no export to an importing country as yet and so no dumping to begin with.

Whether The IA Must Disclose Upon Request The Reasons For Rejecting The Data And Information Supplied By The Applicant And Must Give Details It Took Into Account And Documents Relied On For Constructing The "Export Price" For The Applicant DDC To Be Able To Verify The Calculation Of The Dumping Margin As Required Under Arts 6 And 12 Of The WTO AD Agreement And Sections 18(8) And 38(4) Of The Act

[89] The applicant's complaint is that the respondents acted unreasonably in failing, refusing and or neglecting to use verified data submitted by it to calculate the Dumping Margin in breach of the relevant legal provisions.

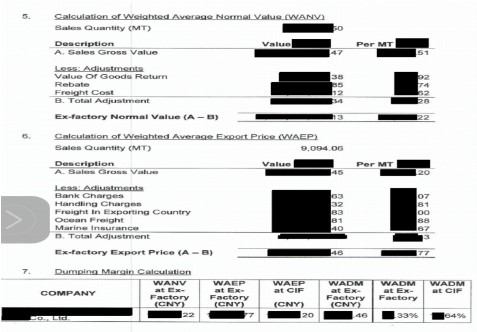

[90] The respondents had refused to use the applicant's data duly verified by them with respect to a) the price of Rebar between DDT and Malaysian Importers; b) the Sales Contract date between DDT and the Malaysian Importers and c) making adjustment to the "export price" by adding the duty drawback to DDC's export price. The calculation based on the applicant's data and methodology is -2.91% which means there was no Dumping.

[91] The principle that an IA must use and take into account verified data and information in an anti-dumping investigation and must provide reasons for rejecting such data and information was highlighted in the case of BX Steel Posco (supra) where the High Court held as follows:

"[29] Further, the information about the compensatory agreement and other related fact which has been verified must be taken into account by the IA in consistent with para 3 and 6 of Annex II: Best Information Available In Terms of para 8 of art 6 of the World Trade Organization Anti-Dumping Agreement, which are as follows:

(i) Paragraph 3.

"All information which is verifiable, which is appropriately submitted so that it can be used in the investigation without undue difficulties, which is supplied in a timely fashion, and, where applicable, which is supplied in a medium or computer language requested by the authorities, should be taken into account when determinations are made. If a party does not respond in the preferred medium or computer language but the authorities find that the circumstances set out in para 2 have been satisfied, the failure to respond in the preferred medium or computer language should not be considered to significantly impede the investigation."

(ii) Paragraph 6.

"If evidence or information is not accepted, the supplying party should be informed forthwith of the reasons therefore, and should have an opportunity to provide further explanations within a reasonable period, due account being taken of the time-limits of the investigation. If the explanations are considered by the authorities as not being satisfactory, the reasons for the rejection of such evidence or information should be given in any published determinations."

[30] In the instant case, the IA has not informed the applicant that the information submitted by the applicant was not accepted."

[Emphasis Added]

[92] Precisely because many variables and factors may go into the calculation of Dumping Margin in a fair comparison between the constructed "export price" and the "normal value" that reasons for rejection of the data and information furnished by the applicant is important for the applicant to verify the AD Duty finally imposed.

[93] The WTO Panel in EU - Anti-Dumping Measures on Imports of Certain Fatty Alcohols from Indonesia, WT/DS442/R has this helpful comment with respect to the minimum standard of disclosure of the result of the verification visit as follows:

"7.228. ..... The results made available or disclosed must nevertheless be sufficiently specific for the interested parties to understand at minimum those parts of questionnaire response or other information supplied for which supporting evidence was requested and whether:

(a) any further information was requested;

(b) the producer made available the evidence and additional information requested;

(c) the investigation authorities were or were not able to confirm the accuracy of the information supplied by the verified companies, inter alia in their questionnaire response.

7.229. Finally, we note that the disclosure obligation in art 6.7 is unqualified and rests entirely on the investigating authorities. The fact that the exporter did not request access to the results of the investigation, or the absence of a demonstrated impact on the due process rights of the exporter, are irrelevant to an evaluation of whether the authorities have complied with art 6.7. Compliance with the provisions of art 6.7 must be assessed solely on the basis of actions taken by the investigating authorities to comply with this provision throughout the investigation."

[Emphasis Added]

[94] Articles 6.4 and 6.7 of the WTO AD Agreement read as follows:

"6.4 The authorities shall whenever practicable provide timely opportunities for all interested parties to see all information that is relevant to the presentation of their cases, that is not confidential as defined in para 5, and that is used by the authorities in an anti-dumping investigation, and to prepare presentations on the basis of this information.

6.7 In order to verify information provided or to obtain further details, the authorities may carry out investigations in the territory of other Members as required, provided they obtain the agreement of the firms concerned and notify the representatives of the Government of the Member in question, and unless that Member objects to the investigation. The procedures described in Annex I shall apply to investigations carried out in the territory of other Members. Subject to the requirement to protect confidential information, the authorities shall make the results of any such investigations available, or shall provide disclosure thereof pursuant to para 9, to the firms to which they pertain and may make such results available to the applicants."

[Emphasis Added]

[95] The High Court appeared to have been more than satisfied with the reasons given by the respondents for rejecting the verified data and information supplied by the applicant in calculating the Dumping Margin as can be gleaned from para 72 of the GOJ as follows:

"The Respondents via the Notice of Essential Facts had provided justification for not taking into account certain information that had been submitted by the Applicant:

(i) Price of Rebar Between DDT and Malaysian Importers ....."

[96] However, upon closer scrutiny, what was purported to be the reasons for rejecting the verified data supplied by the applicant were no more than a regurgitating of facts and an attempt to cite the law as can be seen in the Notice of Essential Facts at paras 49 and 50 thereof as follows:

"Final Price to unaffiliated Malaysian Customer/Exports should be used

49. Diler Iron and Steel Co Inc. requested that the lA should take the final price to unaffiliated Malaysian Customer/Exports in determining the dumping margin

IA's Response

50. The on-site verification visit at the premise of the company has been conducted from 14 to 17 October 2019. The methodology used in determining the export price was made in accordance with the WTO ADA, the Act and its Regulations. The IA is satisfied that the determined export price is comparable at the same level of trade with its normal value."