High Court Malaya, Kuala Lumpur

Su Tiang Joo J

[Civil Suit No: WA-22NCVC-425-07-2018]

24 June 2024

Legal Profession: Duty of care — Claim for general, aggravated and exemplary damages and costs on indemnity basis — Alleged breach of contract and trust and negligence by failure and refusal to account for purchase monies and loan sums received which ought to be remitted to plaintiff — Whether incoming partner should be liable jointly with existing partners to account for monies in clients'/trust account opened prior to incoming partner joining firm and which continued to be held in name of firm after incoming partner joined firm — Whether retired partner of firm should be held jointly liable with existing partners to account for monies in client's/trust account opened whilst still a partner but which were not accounted for to client upon ceasing to be partner — Whether salaried partner of law firm who was held out to be partner of firm liable jointly and severally with other partners — Whether aggravated and exemplary damages warranted

Partnership: Duties — Alleged breach of contract and trust and negligence by failure and refusal to account for purchase monies and loan sums received which ought to be remitted to plaintiff — Claim for general, aggravated and exemplary damages with costs on indemnity basis — Whether incoming partner should be liable jointly with existing partners to account for monies in client's/trust account opened prior to incoming partner joining firm and which continued to be held in name of firm after incoming partner joined firm — Whether retired partner of firm should be held jointly liable with existing partners to account for monies in client's/trust account opened whilst still a partner but which were not accounted for to client upon ceasing to be partner — Whether salaried partner of law firm who was held out to be partner of firm liable jointly and severally with other partners — Whether aggravated and exemplary damages warranted

The plaintiff company had undertaken a housing project (project) and had engaged the 5th defendant law firm (D5) to handle both the sale and purchase transactions, as well as the financing transactions where applicable. The 1st and 2nd defendants (D1 and D2) were at the material time advocates and solicitors practising at D5 and based on D5's letterhead, were held out to be partners of D5 which had offices in Nibong Tebal, Penang and Kota Bharu, Kelantan. D5 subsequently handed over the management of all files, finances and administration in its entirety to the 6th defendant law firm (D6), of which the 2nd and 3rd defendants (D2 and D3) were partners, with effect from 26 June 2013. The plaintiff was accordingly informed of the same by D6, vide letter dated 27 January 2014. The 7th defendant (D7) was the Office and Marketing Manager of D5 and D6, the husband of D2 and was held out to be a partner of D6 in its firm profile, although he was never an advocate or solicitor. D1 denied any involvement in the project and claimed that he had practiced in D5 as a sole proprietor from 2006 until 2012. D1 also asserted that he had nothing to do with D5's branch in Nibong Tebal, Penang and that his law practice was only in Kota Bharu, Kelantan. D6 asserted that as a law firm, it had no legal entity in law and that any findings of liability could only be made against individual defendants, not the law firm itself, and that it had completely ceased operations on 22 September 2019. The 4th defendant (D4) in turn asserted that the facts giving rise to the plaintiff's claim arose prior to her becoming a salaried partner of D6, that D2 and D3 were the only partners of D6 who had conduct of the files pertaining to the project without her involvement, and therefore she should not be held liable. D4 also asserted, in the alternative, that if she were to be held liable, which she denied, her liability should only be limited to the sum of RM278,271.40, being the balance from the total sum received during the period she was in D6, and for which she sought contribution and indemnity from D2 and D3. It was further asserted by D4 and D6 that whilst the purchase monies under the sale and purchase agreements were to be paid to the plaintiff, three cheques totalling RM901,826.00 were issued to third parties and by reason thereof, the plaintiff had waived its right to claim in contract and tort, the purchase monies allegedly received by D5 when it instructed that these payments be made to the third parties. D2, D3, D4, D6 and D7 also raised the defence of limitation and claimed that the plaintiff's action did not accrue within 6 years from the date of filing of the instant action and thus was time-barred under s 6 of the Limitation Act 1953. The plaintiff's claim against the defendants was for inter alia breach of contract and trust, and negligence for the monies received by the defendants which ought to have been remitted to it. The plaintiff also sought general, aggravated and exemplary damages, interest and costs on an indemnity basis. It was contended that except for the sum of RM1,683,222.20, D6 had failed to account and release the balance of the purchase price received from purchasers. D2, D3 and D7 had in a separate action vide Kuala Lumpur High Court Civil Suit No: WA22NCvC-665-10-2020 (Suit 665), sued the plaintiff for legal fees for handling the project and had in the said suit, admitted having received monies totalling RM6,715,653.00 from the purchasers and their financier, Bank Simpanan Nasional Berhad (BSN).

Held (granting judgment in favour of the plaintiff; ordered accordingly):

(1) D2, D3 and D7 having clearly admitted in Suit 665 to receiving the sum of RM6,715,653.00 from cash purchasers and RM1,264,525.00 in loans from BSN, could not be allowed to resile from such admission. Allowing them to do so would be akin to them approbating and reprobating or blowing hot and cold before different courts. (paras 31 & 33)

(2) Based on the evidence adduced, D1 and D2 had represented to the plaintiff's legal advisor (PW5) that they were practising as partners of D5. Therefore, whilst D5 might in fact be a sole proprietorship, both D1 and D5 were estopped from asserting that it was by reason of the representations made. (paras 35-36)

(3) Given the millions of ringgit of purchase price monies flowing into D5's bank account, it was 'most ludicrous' for D1 and by extension, D5, to assert that D1 had not authorised D2 to deal with the plaintiff and that D1 as the alleged sole proprietor had nothing to do with the plaintiff. (para 39)

(4) Regardless of whether D1 was a sole proprietor or partner of D5, D1 had a duty to ensure the proper management of D5's bank accounts in whichever branch the bank accounts were opened. As was held in Alan Michael Rozario v. Merbok MDF Sdn Bhd, the allegation that one partner was not an equity partner of another branch and had no knowledge of the matter did not absolve him in law of his liability as a partner of the firm. Hence D1's assertion that he had no knowledge of the project, was devoid of merit. (paras 41-44)

(5) Given that D1 and D5 were the plaintiff's solicitors for the project, they therefore stood in a relationship of trust and confidence with the plaintiff and were required to account for the monies they had and ought to have received for the benefit of the plaintiff. Until all monies were accounted for, the fact that the monies came to be managed by D2 under the law firm of D6, would not exculpate D1 and D5 from their liability to account for the same by virtue of s 13 of the Partnership Act 1961 (Partnership Act). (paras 47-48)

(6) On the facts, D2 and D3 and by extension D6, were liable to account to the plaintiff for the monies pertaining to the project that they had received, for the benefit of the plaintiff. The fact that D6 was covered by insurance was not a defence at all. (paras 58-59)

(7) There was no distinction made in the Partnership Act that a salaried partner ought to be treated differently. The phrase 'given credit' in s 16 of the Partnership Act had to be construed widely to include any transaction carried out with the firm by a party when dealing with one who, by words spoken or written or by conduct, represented it as a partner. In the circumstances, D4, having held herself out to be a partner of D6, and in the absence of evidence to show that the plaintiff was given notice that D4 had no authority to act in any particular manner, was thus by virtue of ss 7, 8, 12, 13 and 14 of the Partnership Act, jointly and severally liable with the other partners. (paras 76, 77, 78, 97, 124 & 125)

(8) D6, having through D2 given an undertaking to account for clients' monies, i.e., the plaintiff's monies, whichever account the monies were placed in was irrelevant. The duty to account was one of strict liability and the consequences of a breach of that duty would be visited upon the partners of D6, including D4. (paras 87-88)

(9) Both D5 and D6, including their partners, D1 to D4, had failed to ensure that the plaintiff's rights and interests were protected at all times and had acted in breach of their contractual duty of care to the plaintiff. Having failed to discharge their professional obligation to account for the monies, they were jointly and severally liable to account to the plaintiff. (para 90)

(10) On the facts, the defendants had breached their duty to account for the monies received by them, with actual damage having clearly crystallised only upon D6's breach of undertaking in late October 2017. Hence the filing of the plaintiff's suit in July 2018 was clearly within the statutory time limit for filing an action and the defence of limitation, was evidently without merit. As was held in Julian Chong Sook Keok & Anor v. Lee Kim Noor & Anor, the time period for a tortious claim premised on negligence ran from the date of actual damage and not some contingent damage. (para 93)

(11) So long as the monies were not fully accounted to the plaintiff, it was a case of a continuing cause of action involving a running account of the subject monies, and no period of limitation applied. (para 94)

(12) D7 despite not being an advocate and solicitor, having expressly pleaded and held himself out as a partner in Suit 655, and having knowingly allowed himself to be held out as a partner by D2 and the law firm of D6, was liable as a partner of D6 and estopped from denying that he was. An award of costs on an indemnity basis against D7 was appropriate in the circumstances. (paras 102, 104 & 147)

(13) On the facts the three payments totalling RM901,826.00 were made to third parties on the instruction of the plaintiff, and credit for the said payments was given to the defendants. Hence there was no merit to the assertion that the plaintiff had waived its rights to the said monies, nor was there any taint of illegality. Ex facie, the sale and purchase agreements entered into between the plaintiff and the purchasers were not illegal. (paras 109, 113 & 114)

(14) To allow D4 and D6 to take advantage of their illegality plea would be wholly disproportionate to the breaches of their duty of trust and confidence which they owed to the plaintiff. Public interest in preserving the integrity of the justice system should not result in the denial of relief claimed by the plaintiff. (para 118)

(15) The conduct of all of the defendants save for D4, amounted to a deliberate breach of contract and trust and confidence, making an award of exemplary damages appropriate. D1 and D5, who were no longer being involved in the project, ought not to be held accountable for negligence in failing to ensure that the loans were disbursed and collected by D6. (paras 134-135)

(16) D4, although by operation of law was liable together with the partners of D6, was not personally culpable for the breach of trust and confidence, based on the evidence that she had no control of the accounts of D6 and was not personally involved in the project. Hence exemplary damages ought not to be imposed on her. (para 141)

(17) Premised on the facts as asserted by D4 against D2 and D3 which were not denied by them, D4 was to be fully indemnified by D2 and D3 against the judgment pronounced in favour of the plaintiff against all the defendants. (para 146)

Case(s) referred to:

Ahmad Hashim lwn. Tetuan Johari, Nasri & Tan [2013] 2 MLRA 14 (refd)

Alan Michael Rozario v. Merbok MDF Sdn Bhd [2010] 3 MLRA 94 (folld)

Azura Masri v. Perda Ventures Incorporated Sdn Bhd [2023] MLRHU 1871 (refd)

Boustead Trading (1985) Sdn Bhd v. Arab-Malaysian Merchant Bank Berhad [1995] 1 MLRA 738 (refd)

Chang Sean Pong Eddie & Anor v. TVS SCS Malaysia Sdn Bhd [2023] MLRHU 1243 (refd)

Cheah Theam Kheang v. City Centre Sdn Bhd (In Liquidation) And Other Appeals [2011] 2 MLRA 660 (refd)

Cheng Hang Guan & Ors v. Perumahan Farlim (Penang) Sdn Bhd & Ors [1993] 3 MLRH 332 (refd)

Darshan Singh Khaira v. Majlis Peguam Malaysia [2021] 6 MLRA 266 (refd)

Dato' Hamzah Abdul Majid v. Omega Securities Sdn Bhd [2015] 6 MLRA 677 (refd)

Datuk M Kayveas & Anor v. Bar Council [2013] 5 MLRA 437 (refd)

Eastern Shipping Co Ltd v. Quah Beng Kee [1924] AC 177 (refd)

Esso Malaysia Bhd v. Hills Agency (M) Sdn Bhd & Ors [1993] 5 MLRH 142 (refd)

Export-Import Bank Of Malaysia Bhd v. Hisham Sobri & Kadir [2018] MLRHU 1292 (refd)

Express Newspapers Plc v. News (UK) Ltd And Others [1990] 3 All ER 376 (refd)

Guthrie Property Development Holding Bhd v. Baharuddin Hj Ali & Ors [2010] 1 MLRH 215 (refd)

HM Revenue And Customs Commissioners v. Pal And Others [2006] All EWHC 2016 (refd)

Hotel Universal Sdn Bhd v. Lee Guan Par [2003] 7 MLRH 732 (refd)

Julian Chong Sook Keok & Anor v. Lee Kim Noor & Anor [2024] 4 MLRA 131 (folld)

Keow Seng & Company v. Trustees of Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi (Penang) Registered [1983] 1 MLRA 376 (refd)

Kerajaan Malaysia & Ors v. Tay Chai Huat [2012] 1 MLRA 661 (refd)

Kunci Semangat Sdn Bhd v. Thomas Varkki M V Varkki & Anor [2022] 4 MLRA 315 (refd)

Law Society of Singapore v. Zulkifli Mohd Amin And Another Matter [2011] 2 SLR 631 (refd)

Lee Choon Hei v. Public Bank Berhad & Another Appeal [2017] 5 MLRA 693 (refd)

Lynch v. Stiff [1943] 68 CLR 429 (refd)

Madeli Salleh v. Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys & Anor [2005] 1 MLRA 599 (refd)

Majlis Peguam Malaysia v. Lim Yin Yin [2019] 4 MLRA 39 (refd)

Mat Abu Man v. Medical Superintendent General Hospital Taiping & Ors [1988] 1 MLRA 294 (refd)

Messrs Yong & Co v. Wee Hood Teck Development Corp Ltd (1) [1984] 1 MLRA 165 (folld)

Nivesh Nair Mohan v. Dato' Abdul Razak Musa & Ors [2021] 6 MLRA 128 (refd)

Oriental Bank Bhd v. Nordin Hamid & Ors [2011] 1 MLRA 263 (folld)

Peninsular Home Sdn Bhd v. Ko Lim Tristar Sdn Bhd [2024] 2 MLRA 684 (refd)

PJD Regency Sdn Bhd v. Tribunal Tuntutan Pembeli Rumah & Anor And Other Appeals [2021] 1 MLRA 506 (refd)

Poh Chee Seng v. Majlis Peguam [2013] 4 MLRH 700 (refd)

Randhir Singh Bhajnik Singh v. Sunildave Singh Parmar [2019] 6 MLRA 549 (refd)

Rookes v. Barnard And Others [1964] AC 1129 (refd)

Sambaga Valli KR Ponnusamy v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur & Ors And Another Appeal [2018] 3 MLRA 488 (refd)

Shahinuddin Bin Shariff v. Mohd Amin Bin Hasbollah [1998] 4 MLRH 843 (refd)

Solid Investments Ltd v. Alcatel-Lucent (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [2014] 1 MLRA 526 (refd)

Southern Empire Development Sdn Bhd v. Tetuan Shahinuddin & Ranjit & Ors [2008] 1 MLRH 696 (folld)

Tan Keen Keong @ Tan Kean Keong v. Tan Eng Hong Paper & Stationery Sdn Bhd & Ors And Other Appeals [2021] 2 MLRA 333 (refd)

Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat & Anor v. Plenitude Holdings Sdn Bhd [1994] 1 MLRA 420 (refd)

Taz Logistics Sdn Bhd v. Taz Metals Sdn Bhd & Ors [2020] MLRHU 208 (refd)

Tetuan Khana & Co v. Saling Lau Bee Chiang & Anor And Other Appeals [2019] 2 MLRA 112 (folld)

Tham Soon Seong & Anor v. Lee Khai & Ors [2021] MLRHU 608 (refd)

Toh Fong Cheng & Ors v. Pang Choon Kiat & Ors And Another Appeal [2020] 6 MLRA 512 (refd)

Venu Nair & Anor v. Public Bank Berhad [2017] 4 MLRA 261 (refd)

Wan Rohimi Wan Daud & Anor v. Abdullah Che Hassan & Ors And Another Appeal [2016] 3 MLRA 71 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Evidence Act 1950, ss 57(m), 73(1), 106

Legal Profession Act 1976, ss 36, 38, 94(1), (2), (3)

Limitation Act 1953, ss 6, 22(1)

Partnership Act 1890 [UK], ss 14, 17(1)

Partnership Act 1892 [NSW], s 14(1)

Partnership Act 1908 [NZ], s 20(1)

Partnership Act 1961, ss 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 16, 19(1), (2), 23, 24, 25(1)

Rules and Rulings of the Bar Council Malaysia, r 3.02(1), (2)

Rules of Court 2012, O 16 r 8, O 18 r 8(1)(a), (b), (c), O 34 r 2(2)(m), O 49, O 59 r 6(1), O 77 rr 2, 5, 7

The Indian Partnership Act 1932 [Ind], s 31(2)

Counsel:

For the plaintiff: Shailender Bhar (Chia Jia Yee with him); M/s Raihan & Shai

For the 1st & 5th defendants: Muhammad Afiq Ab Aziz (Muhammad Hanis Nasrullah with him); M/s Afiq Aziz & Co

For the 2nd, 3rd & 7th defendants: Mohd Rafiee Noordin; M/s Rafiee & Sani

For the 4th & 6th defendants: Claudia Cheah Pek Yee (Tan Pheng Chew & Natasha Neena Yau Hwee Lynn (PDK) with her); M/s Skrine

JUDGMENT

Su Tiang Joo J:

"Of equal importance, the public too must be able to depend on the honesty and integrity of all practitioners in the legal profession which plays an indispensable role in the administration of justice and conduct of matters in law for members of the public"

(As per Vernon Ong JCA (later FCJ) in Majlis Peguam Malaysia v. Lim Yin Yin [2019] 4 MLRA 39, para [28])

Introduction

[1] In undertaking a housing project, the plaintiff entrusted the seven defendants, four of whom were advocates and solicitors, two were law firms and one who was alleged to be held out to be a partner of one of the law firms, to handle the conveyancing aspect including collecting the purchase price and loan sums for its benefit. The plaintiff sued for inter alia breach of contract and trust and negligence for the monies which ought to have been received by the defendants and remitted to it, general, aggravated and exemplary damages, interest on the monies and damages together with costs on an indemnity basis. After a trial conducted over 12 days, judgment was pronounced in favour of the plaintiff and these are the grounds for the decision made.

[2] In this judgment, the following issues, which are not free from difficulties, are addressed:

(i) whether an incoming partner should be liable jointly and severally with existing partners to account for monies in a client's or trust account which was opened before the incoming partner joined the law firm but with the client's or trust account continuing to be held under the name of the law firm after the incoming partner has joined the law firm;

(ii) whether a retired partner of a law firm should be liable jointly and severally with the existing partners to account for monies in a client's or trust account opened when he was a partner and which were not accounted to the client when he ceased to be a partner of the law firm; and

(iii) whether a salaried partner as well as another person who is not an advocate and solicitor but held out to be a partner of a law firm should similarly be liable jointly and severally with the other partners; and

(iv) whether a law firm and its partners who are said to have relinquished the firm's files for its client but who continue to receive monies under the name of its law firm ought to be jointly and severally liable to account to the client.

Parties

[3] The plaintiff is a statutory body corporate established under the National Land Rehabilitation and Consolidation Authority (Succession and Dissolution) Act 1997. One of its objectives is to look after the welfare of the settlers' community and improve their quality of life and the lives of future generations that follow.

[4] The 1st defendant (Adli Sharidan Sahar or "D1"), 2nd defendant (Nurul Adzliana Ainnie Abdullah or "D2"), 3rd defendant (Mohd Irwan Nizam Khorizan or "D3"), 4th defendant (Norazlina Mat Saad or "D4") were at the material time, advocates and solicitors.

[5] Both D1 and D2 are cousins and the 7th defendant (Nor Azlan Md Huri or "D7") is the husband of D2.

[6] The 5th defendant (Sharidan & Co or "D5") and the 6th defendant (Adzliana & Partners or "D6") are law firms.

[7] D7 was the Office and Marketing Manager of D6. He was also the Office and Marketing Manager of D5 and was held out to be a partner of D6 in D6's firm profile even though it is undisputed that he was never an advocate and solicitor.

Legal Representation Of The Defendants

[8] D1 and D5 are represented by Messrs Afiq Aziz & Co. The other defendants, D2, D3, D4, D6 and D7 had initially retained the same set of solicitors, Messrs Skrine. A common defence was put up. However, new solicitors came in to act for them and an amendment to the defences of D2 and D3 as well as that of D4 and D6 was filed. During the trial, the legal representations of seven defendants were as follows:

(i) D1 and D5 by Messrs Afiq Aziz & Co;

(ii) D2 and D3 by Messrs Fadhly Yaacob & Co;

(iii) D4 and D6 by Messrs Skrine; and

(iv) D7 by Messrs Rafiee & Sani.

[9] D7 had been adjudicated a bankrupt but I was informed during the course of trial by learned counsel, Mr Mohd Rafiee Noordin, that sanction has been obtained from the Director General of Insolvency for D7 to be represented by him and his law firm of Messrs Rafiee & Sani. Prior to obtaining sanction, D7 can be seen diligently attending court on the days the trial was conducted.

Salient Facts - The Project

[10] In early November 2011, the plaintiff undertook a housing project known as Projek Perumahan Kampung Tersusun Generasi Kedua FELCRA Berhad at Seberang Perak, Perak ("the Project").

[11] The total sale value of the Project was estimated to be about RM24,676,168.00.

[12] There were three categories of purchasers of the houses being constructed for the Project namely:

(i) cash purchasers;

(ii) purchasers who took loans from banks, in particular, from Bank Simpanan Nasional Berhad ("BSN"); and

(iii) purchasers who took loans from the Government through the Lembaga Pembiayaan Perumahan Sektor Awam ("LPPSA").

Engagement Of The Law firms Of D5 Followed By D6 For The Project

[13] Evidenced by a letter of appointment dated 2 November 2011 (IDB B1 pp 28 & 29) carrying the caption "Surat Lantikan Peguam Untuk Mengendalikan Urusan Jual beli Unit Rumah Projek Perumahan Kampung Tersusun Generasi Kedua FELCRA Berhad Seberang Perak", D5 was engaged to act for the plaintiff to conduct the sale and purchase transactions for the Project. It also acted in the financing transactions where applicable.

D1 - A Sole Proprietor Of D5?

[14] Both D1 and D2 were advocates and solicitors of D5.

[15] If D5 was a sole proprietorship as alleged by D1, this ought to have been made clear in its letterhead as is required by r 3.02(1) of the Rules and Rulings of the Bar Council Malaysia which provides that:

"Sole proprietor/partner

The name of the sole proprietor or every partner in a law firm must be stated on the firm's letterhead."

[16] Indeed, it is also provided that the names of the legal assistants in a firm, if stated, must be distinguished from those of the sole proprietor or partners of the firm, see r 3.02(2) of the Rules and Rulings of the Bar Council Malaysia. This rule is reproduced hereunder:

"Legal Assistants

(a) The names of the legal assistants in a firm, if stated, must be distinguished from those of the sole proprietor or partners of the firm."

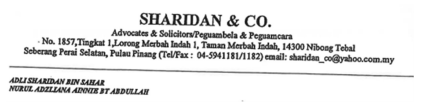

[17] These rules are sensible and helpful as they would assist those having any dealings with a law firm to ascertain who are the principals and who are the employee advocates and solicitors. The letterhead of D5 did not have any feature to distinguish the position of D1 and D2. Instead, from the letters carrying the letterhead of D5, both D1 and D2 were held out to be partners (IDB B1 see for example pp 30, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38) and a copy of D5's letterhead is reproduced hereunder.

[18] That these rules have to be obeyed can be seen from s 94(1), (2) and (3) of the Legal Profession Act 1976 where an advocate and solicitor who is found guilty of misconduct for any breach of rules of practice and etiquette of the profession made by the Bar Council shall be liable to be:

(a) struck off the Roll;

(b) suspended from practice for any period not exceeding five years;

(c) ordered to pay a fine not exceeding fifty thousand ringgit; or

(d) reprimanded or censured.

Subsequent Engagement Of D6

[19] On or about June 2014, the plaintiff was notified by letter dated 27 January 2014 (IDB B1 p 39) under the letterhead of D6 that D5 has handed over the management of all files, finances and administration in its entirety to D6 with effect from 26 June 2013. In its original language, the relevant part of this letter says:

"Untuk makluman pihak tuan/puan, Tetuan Sharidan & Co telah menyerahkan pengurusan kepada Tetuan Adzliana & Partners bermula 26 Jun 2013. Pertukaran tersebut melibatkan semua perkara seperti penyerahan fail-fail yang dikendalikan, kewangan serta pentadbiran secara keseluruhan."

[20] In this letter by D6 to the plaintiff, the letterhead carries the names of D2 and D3 as its partners. That D2 and D3 practiced in partnership is an agreed fact (Encl 122 para 2).

[21] In D6's firm profile (IDB B1 pp 42 to 62 @ p 44) it was prominently set out that it was form erly known as D5 which was first established in December 2002 and continued until May 2013, and that with effect from June 2013, D5 changed its name, from Messrs Sharidan & Co to that of Messrs Adzliana & Partners (D6).

Plaintiff's Claims

[22] The plaintiff completed the Project and delivered vacant possession of the houses constructed to the purchasers in late 2014. Between 2015 and 2017, the plaintiff requested, inquired and demanded from D6 to account and release the purchase price received. These requests were made on multiple occasions. Many of these inquiries and demands went unanswered. Only six payments totalling RM1,683,222.20 were released to the plaintiff (IDB B1 pp 11 to 107, IDB B1 pp 113 to 116 and IDPT (1) p 39), made up of three payments totalling RM901,826.00 by D5 and three payments totalling RM781,396.20 by D6.

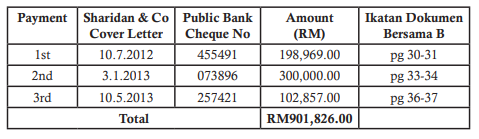

[23] The payments made by D5 and D6 were helpfully tabulated by the plaintiff in PW5's witness statement (PWS-5) in Q & A 15 and supplemented in Q & A 36(a) to (c) and is reproduced here.

"Q15: What monies were released to FELCRA at that time?

A15: Between 10 July 2012 to 10 May 2013, Sharidan & Co only released the following arbitrary payments to FELCRA:

Q36: What was the response by Adzliana & Partners to the FELCRA letters dated 4 May 2016 and 9 May 2016 mentioned above? Was there any release of monies?

A36: Adzliana & Partners did not release RM5,751,174.00 in accordance with their undertaking. Neither did Adzliana & Partners release the monies in relation to PT 8908. Instead, Adzliana & Partners only released a total sum of RM781,396.20 via 3 separate arbitrary payments:

(a) Vide Public Bank Cheque No 072159 dated 27 June 2016, a payment was made for the amount of RM404,512.20, being the balance purchase price paid by 6 cash purchasers. [See: Ikatan Dokumen Bersama B, pp 101-103];

(b) Vide Public Bank Cheque No 072179 dated 19 August 2016, a payment was made for the amount of RM46,636.20, being the balance purchase price paid by 1 cash purchaser. [See: Ikatan Dokumen Bersama B, pp 104-107];

(c) Vide Public Bank Cheque No 353393 dated 13 April 2017, a payment was made for the amount of RM330,247.80, being the balance purchase price paid by 5 cash purchasers. [See: Ikatan Dokumen Bersama B, pp 113116 and Ikatan Dokumen Tambahan Plaintif (1), p 39].

This 3rd payment was only made after FELCRA had discovered that the titles of 5 other houses had been transferred to the purchasers upon conducting its own land searches and thereafter, made inquiries to Adzliana & Partners for the release of full purchase price via letter dated 29 March 2017 [See: Ikatan Dokumen Bersama B, pp 109110]."

[24] Undoubtedly disappointed and upset, the plaintiff teRM inated the services of D6. A new set of solicitors, Messrs Abdul Rahman & Partners, was appointed to take over the conduct of the Project. They contacted D6. By letter dated 26 October 2017 (IDB B1 p 217) to the new set of solicitors, D2 on behalf of D6 said inter alia:

"For your information, we are still checking the amount of client's monies held in our account. We undertake to forward to you the details and how it will be transfer (sic) to your account before the last date to transfer the files".

[25] In breach of its undertaking, D6 did not provide the details.

[26] Instead, the plaintiff had to suffer the gross inconvenience of reconstructing the financials on the monies received by D5 and D6. This, it did from documents obtained from D6 and various other sources including the purchasers, BSN, the Bar Council, and the police, who upon a report lodged, had seized files from D6.

[27] After reconstructing the financials, the following evidence was produced through PW5:

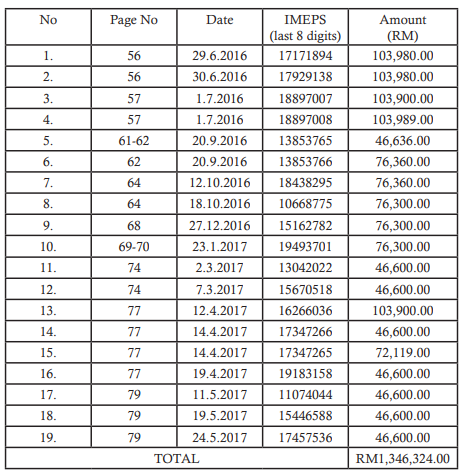

"Q61: Please refer to pp 11-98 of Ikatan Dokumen Bersama B2. Can you tell us what is this document?

A61: This is a document that was produced by Adzliana in the Advocates & Solicitors Disciplinary Board proceedings. It shows a letter dated 14 December 2018 from Public Bank to Skrine enclosing Adzliana & Partners' Bank Statements for Account No 3189063434 from April 2014 to November 2018. The Bank Statements correspond with the list given by BSN to FELCRA, in that it shows a total of 19 BSN loans had been disbursed to Adzliana & Partners. The Bank Statements also show the exact amount of loan sum (without insurance) received by Adzliana & Partners from Unit Kredit Perak BSN - RM1,346,324.00 in total. Each individual transaction for the 19 BSN loans can be found at the following page:

Q62: What is the total differential price that Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners received for these 19 houses?

A62: Since the loans had been disbursed by BSN, Sharidan & Co and/ or Adzliana & Partners must have received or ought to have received full differential price for these 19 houses from the purchasers. The total sum is RM185,714.00.

Q73: What is the total sum of the 15 houses that ought to have been received by Defendants?

A73: Since the houses had been transferred and charged, the total sum that ought to have been received by Defendants is RM1,225,682.00, ie, the full purchase price of all 15 houses. FELCRA is also claiming this amount. I have prepared a table consisting the breakdown of these 15 houses, and attached it at "ATTACHMENT A" at the back of my Witness Statement.

Q78: What is the total purchase price received by Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners from these 96 cash purchasers?

A78: The total purchase price received by Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners from the 96 cash purchasers is RM6,075,806.70. FELCRA is claiming this amount as well.

The breakdown of the payment made by each cash purchaser to Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners can be found at "ATTACHMENT B", which I have prepared and attached as part of my Witness Statement.

I would also like to state that the advice given by Adzliana & Partners vide their letter dated 7 August 2017 to FELCRA's new solicitors was incorrect. In the annexure to the letter, they advised that there were only 93 cash purchasers [See: Ikatan Dokumen Bersama B2, pp 209211].

Q81: What is the total differential price received by the Defendants from these 132 BSN purchasers?

A81: The total differential price received by Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners from the 132 BSN purchasers is RM1,182,710.84. For the breakdown of the payment received by the Defendants from each BSN purchaser, I have prepared "ATTACHMENT C" and enclosed it as part of my Witness Statement.

Q83: From the LPPSA documents referred to earlier, what is the initial deposit / booking fees received by Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners from these 72 LPPSA purchasers?

A83: The total initial deposit / booking fees and deposit received by Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners from the 72 LPPSA purchasers is RM50,536.20. I have prepared a breakdown, listing out the initial deposit / booking fees received by Sharidan & Co and/or Adzliana & Partners, and enclosed it as "ATTACHMENT D" at the back of my Witness Statement.

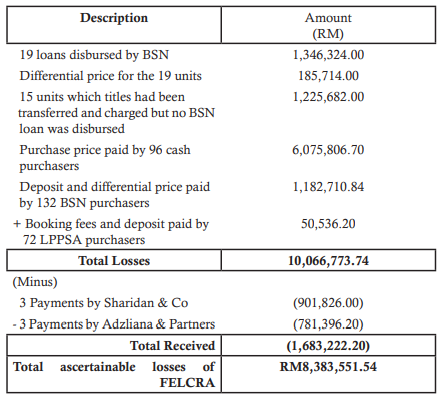

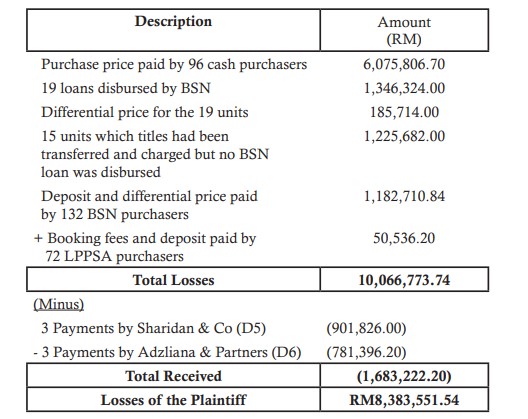

[28] From the above evidence led through the Legal Advisor of the plaintiff, Amirah Kausar Binti Basiron (PW5), the accounts were put together and set out in Attachments A to D of her witness statement (PWS-5). After taking into account the aforesaid six payments released by D5 and D6, the total ascertainable losses suffered by the plaintiff were tabulated as follows (PWS-5 Q&A 84):

"Q84: From the records now available to FELCRA and filed in Court, what are the ascertainable losses suffered by FELCRA?

A84: Taking into account the 3 payments released by Sharidan & Co and Adzliana & Partners respectively, the total ascertainable losses suffered by FELCRA is RM8,383,551.54 with the following breakdown:

Court's Analysis And Findings

[29] I begin by making an overall analysis of the evidence led by the plaintiff. I will then deal with the defences put up by all the defendants. The latter falls into four groups:

(i) D1 and D5;

(ii) D2 and D3;

(iii) D4 and D6, and

(iv) D7.

Admissions, Approbate And Reprobate

[30] It is settled law that admissions are the strongest evidence (see Esso Malaysia Bhd v. Hills Agency (M) Sdn Bhd & Ors [1993] 5 MLRH 142) and admissions in pleadings or judicial admissions stand on a higher footing than evidentiary admissions, and such admissions by themselves can be made the foundation of the rights of the parties, see Madeli Salleh v. Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys & Anor [2005] 1 MLRA 599 where at para [47], His Lordship Clement Skinner J speaking for the Court of Appeal said:

"[47] In support of what we say we would refer to Sarkar's Law of Evidence at p 313 under the topic 'Admissions in Pleadings' where it is said:

Admissions in pleadings or judicial admissions stand on a higher footing than evidentiary admissions. The former are fully binding on the maker and constitutes a waiver of proof whereas the latter are not conclusive and can be shown to be wrong. (Nagindas v. Dalpatram AIR [1974] SC 471). Admissions in pleadings or judicial admissions by themselves can be made the foundation of the rights of the parties (Satish Mohan Bindal v. State of UP AIR [1986] All 126 128, [1985] All CJ 507."

[31] By way of Kuala Lumpur High Court Civil Suit WA-22NCvC-665-10-2020 ("Suit 665"), D2, D3 and D7 had sued the plaintiff for inter alia legal fees for handling the Project ("Suit 665"). In Suit 665 (IDTP 1 pp 40 to 55 @ 49 paras 17 to 19), they pleaded that they had received a sum of RM5,451,118.00 from cash purchasers and RM1,264,535.00 in loans from BSN with the total receipt being RM6,715,653.00. This is a clear admission by D2, D3 and D7.

[32] As the instant action is in the main, one against advocates and solicitors (save for D7 but who is held out to be one), it is appropriate to hearken to the words of our Chief Justice, the Right Honourable Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat in Her Ladyship's decision in Nivesh Nair Mohan v. Dato' Abdul Razak Musa & Ors [2021] 6 MLRA 128 at para [36] where Her Ladyship said:

"[36] We pause for a moment here to note that our case law is replete with reminders to advocates - whether from the Bar or public service - of the onerous duties of those in the legal profession. The highest duty of counsel - a duty which supersedes his or her duty to his client - is his duty to the court, which remains paramount in the administration of justice. Counsel are expected to make out their client's case to the best of their abilities but they cannot adopt the mindset that they must "win at all costs" if that results in misleading the court or approbating and reprobating before different panels of the court."

[33] D2, D3 and D7 cannot be allowed to resile from such an admission. To allow them to do so would be akin to them approbating and reprobating or blowing hot and cold before different courts, which the court would not countenance. See also Cheah Theam Kheang v. City Centre Sdn Bhd (In Liquidation) And Other Appeals [2011] 2 MLRA 660 at para [105] where the Court of Appeal cited and adopted the following words of Sir Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson VC in Express Newspapers Plc v. News (UK) Ltd And Others [1990] 3 All ER 376:

"There is a principle of law of general application that it is not possible to approbate and reprobate. That means you are not allowed to blow hot and cold in the attitude that you adopt. A man cannot adopt two inconsistent attitudes towards another: he must elect between them and, having elected to adopt one stance, cannot thereafter be permitted to go back and adopt an inconsistent stance".

As Against D1 And D5

[34] In summary, D1's defence is one of denial. He denies that he was involved in the Project. He asserted that he practiced in D5 as a sole proprietor. D1 sought to rely upon the particulars of the Malaysian Bar's records (IDB A pp 4 to 7) as conclusive proof that he was practicing as a sole proprietor in D5 for the period from 2006 until 2012. This document was classified as a Part A document, and thus its contents are admitted both as to authenticity and contents; see O 34 r 2(2)(m) Rules of Court 2012.

[35] However, the plaintiff led credible evidence to show that D1 and D2 had represented to PW5 that they were practicing as partners of D5 (PWS-5 Q&A 5). The evidence led were:

(i) In D5's firm profile for the year 2011 (IDB B1 p 10) it was represented that D5 has two partners, D1 and D2. It will be recalled that D5 was engaged for the Project by the plaintiff vide a letter of appointment dated 2 November 2011 (IDB B1 pp 28 & 29); and

(ii) In the Malaysian Bar Professional Indemnity Insurance Certificate for the period from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2011, both D1 and D2 were the named insured and both were said to carry the position of partners of the firm of D5.

[36] Therefore, whilst D5 may in fact be a sole proprietorship - as against the plaintiff - I find that both D1 and D5 are estopped from asserting that it was by reason of the representations made. See Boustead Trading (1985) Sdn Bhd v. Arab-Malaysian Merchant Bank Berhad [1995] 1 MLRA 738 where His Lordship Gopal Sri Ram JCA (later FCJ) speaking for the Federal Court said:

"The time has come for this Court to recognise that the doctrine of estoppel is a flexible principle by which justice is done according to the circumstances of the case. It is a doctrine of wide utility and has been resorted to in varying fact patterns to achieve justice. Indeed, the circumstances in which the doctrine may operate are endless.

Edgar Joseph Jr. J. (as he then was) in an illuminating judgment in Alfred Templeton & Ors v. Low Yat Holdings Sdn Bhd & Anor [1989] 1 MLRH 144 applied the doctrine in a broad and liberal fashion to prevent a defendant from relying upon the provisions of the Limitation Act 1953.

The doctrine may be applied to enlarge or to reduce the rights or obligations of a party under a contract: Sarat Chunder Dey v. Gopal Chunder Laha LR [1889] 19 IA 203; Amalgamated Investments & Property Co Ltd v. Texas Commerce International Bank Ltd [1982] QB 84. It has operated to prevent a litigant from denying the validity of an otherwise invalid trust (see, Commissioner For Religious Affairs Trengganu & Ors v. Tengku Mariam Tengku Sri Wa Raja & Anor [1970] 1 MLRA 452) or the validity of an option in a lease declared by statute to be invalid for want of registration (see, Taylor Fashions Ltd v. Liverpool Victoria Trustees Ltd [1981] 2 WLR 576). It has been applied to prevent a litigant from asserting that there was no valid and binding contract between him and his opponent (see, Waltons Stores (Interstate) Ltd v. Maher [1988] 164 CLR 387) and to create binding obligations where none previously existed (see, Spiro v. Lintern [1973] 1 WLR 1002. It may operate to bind parties as to the meaning or legal effect of a document or a clause in a contract which they have settled upon (see the Amalgamated case (supra)) or which one party to the contract has represented or encouraged the other to believe as the true legal effect or meaning: The American Surety Co of New York v. The Calgary Milling Co Ltd [1919] 48 DLR 295; De Tchihatchef v. The Salerni Coupling Ltd [1932] 1 Ch 330; Taylor Fashions (supra)."

[37] With respect, D1's defence that he and by extension, D5, is not aware of the Project, is incredible and flies in the face of the following evidence led:

(i) The numerous sale and purchase agreements clearly states that the law firm of D5, of which D1 professed to be the sole proprietor, is the firm of solicitors on record acting for the plaintiff as the vendor;

(ii) The numerous letters issued by D5 to the purchasers asking for payments of purchase price and legal fees;

(iii) Receipts issued by D5 as well as bank-in transaction slips showing payments into D5's bank account; and

(iv) The three payments amounting to RM901,826.00 paid by D5 to the plaintiff.

[38] In my considered view, adopting the words of His Lordship Syed Agil Barakbah FCJ (later LP) said in Messrs Yong & Co v. Wee Hood Teck Development Corp Ltd (1) [1984] 1 MLRA 165 at p 170, these evidence amount to:

"....ample evidence on record for the learned Judge to conclude that a retainer came into existence by implication and as amplified by the conduct of the parties which showed a course of dealings giving rise to legal obligations and establishing the relationship of solicitor and client."

[39] D2 in her evidence said that she had informed D1 of the Project upon D5 having been appointed to manage it. With the millions of ringgit of purchase price money flowing into the bank account of D5, I agree with the plaintiff that it is "most ludicrous" for D1, and by extension, D5, to assert that he (D1) did not authorize D2 to deal with the plaintiff, and that he (D1) as the alleged sole proprietor, has nothing to do with the plaintiff.

[40] There are elaborate rules under inter alia the Solicitor's Account Rules 1990, Advocates and Solicitors (Issue of Sijil Annual) Rules 1978, and the Accountant's Report Rules 1990 which imposes upon an advocate and solicitor a duty to pay client's money into a client account, and to declare all accounts he has opened. These accounts have to be audited and an accountant's report must be put up before the advocate and solicitor can be issued a Sijil Annual to enable him or her to apply for a practising certificate.

[41] Therefore, I agree with learned counsel for the plaintiff, regardless of whether D1 is a sole proprietor or a partner of D5, the law casts a duty upon him to ensure the proper management of D5's bank accounts in whichever branch the bank accounts may be opened. In Law Society Of Singapore v. Zulkifli Mohd Amin And Another Matter [2011] 2 SLR 631 which was cited with approval by our Federal Court in Datuk M Kayveas & Anor v. Bar Council [2013] 5 MLRA 437 at para [54] the following pertinent findings were made:

"The very fact that Zulkifli was able to abscond with more than $11m showed that Sadique breached his duty as a co-signatory to supervise the client account. Sadique's cavalier attitude towards supervising the firm's accounts facilitated Zulkifli's crime. His argument that he had agreed with Zulkifli to divide responsibilities between themselves and was thus not liable for his failure to supervise the accounts as this task fell under Zulkifli's purview was completely without merit".

[42] D1 sought to distance himself from D5's branch in Nibong Tebal, Penang by asserting that his law practice was only in Kota Bharu, Kelantan and that he had nothing to do with the branch in Nibong Tebal in Penang. However, D1 has agreed as a fact that he and D2 were advocates and solicitors practicing in Sharidan & Co (D5) with offices in Nibong Tebal, Penang and Kota Bharu (see Agreed Facts of D1 in D1 and Agreed Facts of D2, D3 and D7 in D2). Therefore, his attempt to distance himself from the Nibong Tebal branch in Penang not only sounds hollow but directly contradicts what he had agreed as a fact.

[43] In any event, as held by the Court of Appeal in Alan Michael Rozario v. Merbok MDF Sdn Bhd [2010] 3 MLRA 94 the allegation that one partner was not an equity partner of another branch and that he had no knowledge of the matter does not absolve him in law of his liability as a partner of the firm.

[44] In the circumstances, I find the assertion by D1 that he has no knowledge of the Project to be wholly devoid of merit and in fact, a barefaced lie.

[45] To add insult to injury, D1 asserted that it was for the plaintiff to do its due diligence or "background check" to ascertain the actual status of the firm. D1 has conveniently or willfully chosen to forget that an advocate and solicitor is a member of the legal profession which is an honourable profession. In Majlis Peguam Malaysia v. Lim Yin Yin [2019] 4 MLRA 39 para [28]) His Lordship, Vernon Ong JCA (later FCJ) pointedly said:

"Of equal importance, the public too must be able to depend on the honesty and integrity of all practitioners in the legal profession which plays an indispensable role in the administration of justice and conduct of matters in law for members of the public."

[46] So high is the regard accorded to members of the legal profession that under the Evidence Act 1950 ("EA 1950"), the court is expressly enjoined to take judicial notice that any advocate and solicitor who appears before it is so authorized to appear or act before it, without question, see s 57(m) EA 1950. Judicial notice means that no fact of which the court will take judicial notice need be proved, see s 57 EA 1950. As was said by His Lordship, Lee Swee Seng JC (now JCA) in Poh Chee Seng v. Majlis Peguam [2013] 4 MLRH 700 at para [1]:

"Our word is our bond! In no profession is this more expected of and exacted from than members of the honourable legal profession. Truth and trustworthiness are hallmarks of the profession .... On them are reposed the trust of clients and third parties where their monies, assets, wealth and rights are concerned ...."

[47] I find that D1 and D5 were the plaintiff's solicitors for the Project. By reason thereto, they stand in a relationship of trust and confidence with the plaintiff, and must account to the plaintiff the monies it has and ought to have received for the benefit of the plaintiff. See Wan Rohimi Wan Daud & Anor v. Abdullah Che Hassan & Ors And Another Appeal [2016] 3 MLRA 71 where His Lordship, Vernon Ong JCA (later FCJ) at para [28] held:

"[28] In this case, the incontrovertible fact is that the defendants were acting as solicitors for the plaintiffs in the FELDA suit; the payments were made to defendants in their capacity as solicitors for the plaintiffs. As solicitors for the plaintiffs in the FELDA suit, the defendants stand in a fiduciary relationship of trust and confidence with the plaintiffs. As to the meaning of fiduciary, it is instructive to refer to the instructive passages at pp 744, 745 and 747 of the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Alcatel-Lucent (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v. Solid Investments Ltd & Another Appeal (supra).

A fiduciary is someone who has undertaken to act for or on behalf of another in a particular matter in circumstances which give rise to a relationship of trust and confidence. A fiduciary must act in good faith; he must not make a profit out of his trust; he must not place himself in a position where his duty and interest may conflict; he may not act for his own benefit or the benefit of a third person without the informed consent of his principal. The distinguishing obligation of fiduciary is the obligation of loyalty. The principal is entitled to the single minded loyalty of his fiduciary. (See: Bristol And West Building Society v. Mothew (t/a Stapley & Co) [1996] 4 All ER 698, the English Court of Appeal).

The accepted traditional categories of fiduciary relationship usually arise in matters involving trustee beneficiary, agent-principal, solicitor-client, employee-employer, director-company, and partners' inter se relationships. Unless expressly provided for in an agreement commercial transactions falling outside the accepted traditional categories of fiduciary relationship (as in the present case) often do not give rise to fiduciary duties, because they do not meet the criteria for characterisation as fiduciary in nature. (See: John Alexander Clubs (supra).

From the above authorities, for there to exist a complete cause of action for taking of accounts, the respondent has to plead and prove the following:

(a) the appellant (as the defendant) must be liable to pay a certain sum of monies to the respondent (as the plaintiff); and

(b) the appellant (as the defendant) is an accounting party to the respondent (the plaintiff).

[29] Applying the well-established principles enunciated above, we hold that the defendants qua solicitors for the plaintiffs in the FELDA suit stand in a relationship of trust and confidence with the plaintiffs; accordingly, the defendants are therefore fiduciaries and the payments were received by the defendants in their capacity as fiduciaries for the plaintiffs. Consequently, the defendants are liable to pay the judgment sum to the plaintiffs. As such, the defendants are an accounting party to the plaintiffs."

[48] The plaintiff was notified by letter dated 27 January 2014 (IDB B1 p 39) under the letterhead of D6, that D5 has handed over the management of all files, finances and administration in its entirety to D6 with effect from 26 June 2013. However, in my judgment, until and unless all monies are fully accounted for, the fact that the monies came to be managed by D2 under the law firm of D6, would not exculpate D1 and D5 from their liability to account. This is expressly provided by s 13 of the Partnership Act 1961 ("Partnership Act") which provides that:

"Misapplication of money or property received for or in custody of firm

In the following cases, namely:

(a) where one partner, acting within the scope of his apparent authority, receives the money or property of a third person and misapplies it; and

(b) where a firm in the course of its business receives the money or property of a third person, and the money or property so received is misapplied by one or more of the partners while it is in the custody of the firm, the firm is liable to make good the loss."

[49] I derive further support from the judgment of His Lordship Mohd Hishamudin Md Yunus J (later JCA), in Southern Empire Development Sdn Bhd v. Tetuan Shahinuddin & Ranjit & Ors [2008] 1 MLRH 696 (cited with approval by the Court of Appeal in Toh Fong Cheng & Ors v. Pang Choon Kiat & Ors And Another Appeal [2020] 6 MLRA 512 at para [11] (infra)) who held as follows:

"[17] In my judgment, because in law the liability of the firm is distinct from that of the partners, therefore, the liability of the firm is not affected by any partner ceasing to be a partner of the firm. Although the particular errant partner has long left the partnership, the liability of the firm still continues - subject only to any law pertaining to limitation of actions.

[18] This, to my mind, must be the correct interpretation of the law pertaining to partnership; otherwise there will be chaos in the commercial world; for, if the 1st defendant's proposition were to be accepted, then a partnership which has incurred a liability can easily exonerate itself from that liability simply by asking the particular errant partner in question to leave the firm.

Surely, this cannot be the law."

As Against D2 And D3

[50] In their submissions filed (E304), D2 and D3 asserted that:

(a) D6 was lawfully appointed by the plaintiff;

(b) each and every instruction given by the plaintiff has been complied with and from the evidence of D2, monies received have been paid to the plaintiff:

(c) the relationship between D6 and the plaintiff started to become strained when D6 issued an invoice for RM1,300,000.00 for legal fees which the plaintiff refused to make any payment;

(d) D2 and D3 have used the police and the Malaysian Bar Council to seize all files pertaining to the Project on the premise that D6 had failed to hand over monies for the Project;

(e) the plaintiff has failed to prove that D2 and D3 as partners of D6 had taken the monies pertaining to the Project;

(f) it is settled law that the burden of proof lies on the plaintiff to prove its loss. Reference was made to the case of Peninsular Home Sdn Bhd v. Ko Lim Tristar Sdn Bhd [2024] 2 MLRA 684 at para [66];

(g) evidence led shows that monies were paid to D5, and thus D2 and D5 as well as the law firm of D6 ought not to be responsible for the monies paid to D5. And, the plaintiff has failed to prove how much was received by D5 and D6;

(h) the minutes of a meeting held on 13 May 2015 between the plaintiff on the Project attended by PW5 and D7, did not show any discussion of there being any monies that have not been paid by D6 to the plaintiff;

(i) that the plaintiff has failed to show any negligence on the part of D6;

(j) that D6 at all material time is covered by insurance; and

(k) D2 and D3 have not been charged, let alone, convicted of any criminal charges.

Burden Of Proof

[51] It is true that the legal burden is on the plaintiff to first prove its case that the defendants, and in particular D2, D3 and D6 have to account to it for the monies received pursuant to the Project. In my considered view, the plaintiff has discharged this legal burden on a balance of probabilities when it led evidence to prove that:

(i) By letter dated 27 January 2014 (IDB B1 p 39) D6 informed the plaintiff that D6 has taken over from D5 all the files, finances and management of the Project commencing 26 June 2013 and by reason thereto a solicitor-client relationship came into being between D2 and D3 as partners of D6 with the plaintiff. And, pursuant to this relationship, D2 and D3, and by extension, D6 each owes a duty to account;

(ii) By letter dated 26 October 2017 (IDB B1 p 217) to the new set of solicitors taking over from D6, D2 had on behalf of D6, undertaken to forward to the new solicitors the details of the amount of client's monies held in its account, and how the monies were to be transferred to the account of the new solicitors. D2, D3 and D6 did not make good on this undertaking which in any event, is an obligation imposed upon them as fiduciaries by law. And, this letter is an admission by them that they have to account to the plaintiff;

(iii) Even after D6 had taken over the management of the files for the Project, purchase monies continue to be paid in the name of D5 with receipts issued by D6;

(iv) D2 and D3 have in Suit 665 admitted in pleadings that they have received a sum of RM5,451,118.00 from cash purchasers and RM1,264,535.00 in loans from BSN with the total receipt being RM6,715,653.00, but D6 had paid over only a sum of RM781,396.20; and

(v) That 15 units of houses were charged to BSN and the houses transferred to the purchasers but the loans amounting to RM1,225,682.00 were not released to the plaintiff. D2 and D3 were partners of D6 who were the transactional solicitors for these loans. Thus, it is clear that D2 and D3 were also negligent here when it breached its duty of care owed to the plaintiff by failing to have the loans released to D6 for the benefit of the plaintiff.

[52] It is unfortunate that learned counsel for D2 and D3, whose duty is to the Court, found it fit not to address these pieces of evidence in his submissions. See the admonition by Chief Justice of Malaysia in Nivesh Nair Mohan (supra). Further, the minutes of the meeting of 13 May 2015 were not even challenged by way of cross-examination during the plaintiff's case, and neither were the contents ever put to any of the plaintiff's witnesses. Instead, these minutes were only raised for purposes of the indemnity claim filed by D4 against D2 and D3.

[53] Once the plaintiff has discharged its legal burden, the evidential burden shifts to D2 and D3 to account, see Randhir Singh Bhajnik Singh v. Sunildave Singh Parmar [2019] 6 MLRA 549 at para [8]. Unfortunately for the plaintiff, its repeated requests and demands to the defendants yielded no positive response. Even during the trial, D2 who was the main transactional solicitor was evasive when asked about the accounts.

[54] I agree with the plaintiff that D2 and D3 have utterly failed to account for the monies which were inexplicably missing from D6's account. In this regard, the minutes of a meeting held on 2 October 2015 (IDB (B1) E136 p 96) attended by D2 and D7 on behalf of D6, recorded that as at 1 October 2016, D6 had collected RM8,557,854.00 from 230 purchasers who had either paid cash or the difference between their loans from LPPSA and the purchase price and who had gone into occupation of their houses.

[55] The collection by D6 of the sum of RM8,557,854.00 was affirm ed by PW5 in her witness statement (Q&A 32 and 33 in PWS-5). However, D6's principal account number 3189063434 in Public Bank Berhad for the Project recorded a balance of a mere RM110,000.00 when the meeting of 2 October 2016 was held (IDB B2 p 38).

[56] Under cross-examination by learned counsel for D4 and D6 on whether the sum of RM8,557,854.00 collected as at 1 October 2016 has been paid over to the plaintiff, PW5 replied "No" (NOP p 239 lines 6 to 9).

[57] D2 testified that only 2 accounts were used for the purposes of the Project, ie, Sharidan & Co, Public Bank Account No: 3169273633 and Adzliana & Partners, Public Bank Account No: 3189063434. However, when D2 was asked further whether Adzliana & Partners' Bank Islam account received purchase price under the Project, she answered that she was not sure. Such an answer from one who has to account is wholly unacceptable. This shows that D2 was not accounting for the receipt of purchase price as required of her. On this score, D2 had also contradicted her defence and her earlier testimony that D6 maintained only one bank account, ie, Public Bank Account No: 3189063434 when it was shown that D6 has one other Public Bank account and this other account in Bank Islam which D2 was unable or to put it bluntly, has refused to account.

D6 Having Insurance

[58] That D6 was covered by insurance is not a defence at all. It is for D6 to claim from its insurers. Similarly, that there is no evidence that D2 and D3 have been convicted or charged with any criminal charges and therefore should not be held liable in this civil action, is a self-serving averment which is devoid of merit. In fact, D2 and D3 have not pointed to any law that would exculpate them of any liability premised on these two assertions of theirs. Instead, it is trite that a party can be held liable under civil proceedings without having to be convicted of any criminal charges.

[59] Wherefore, I find that D2 and D3 and by extension, D6 are liable to account to the plaintiff for the monies pertaining to the Project which they received for the benefit of the plaintiff. How much they are liable, will be discussed in detail later on when I come to deal with the relief that is to be awarded to the plaintiff.

As Against D4 And D6

Whether Judgment Can Be Entered Against A Law firm

[60] D6 asserts that it is a law firm and thus, has no legal entity in law. It has completely ceased operations on 22 September 2019, and D6 takes the position that any findings of liability can only be made against an individual defendant, not a law firm. Even if the plaintiff is successful in establishing liability against [all] the defendants, D6 asserts no judgment should be entered against D6, and during the presentation of oral submissions on 15 March 2024, learned counsel for D4 and D6, asserted this would hold true as against D5 as well. D5 did not make such an assertion, and how could it, when its position is that it is a sole proprietorship? However, I do acknowledge that I have held above that D1 is estopped from asserting that it is not a partnership and will now deal with whether a judgment can be entered against a firm.

[61] Reliance was placed by D4 and D6 on the Federal Court authority of Keow Seng & Company v. Trustees of Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi (Penang) Registered [1983] 1 MLRA 376 at p 379 where Raja Azlan Shah LP (later His Majesty) said:

".... A partnership firm is not a legal entity in law..... The firm name is not in itself the name of any person other than the partners because in the words of Farewell LJ in Sadler v. Whiteman:

'....the firm name is a mere expression, not a legal entity....'

When a firm's name is used, it is only a convenient method for denoting those persons who compose the firm at the time when that name is used, and a plaintiff who sues partners in the name of their firm in truth sues them individually, just as much as if he had set out all their names"

[62] Reference was also made by learned counsel for D4 and D6 to the authorities of Shahinuddin Bin Shariff v. Mohd Amin Bin Hasbollah [1998] 4 MLRH 843 at 852, and Hotel Universal Sdn Bhd v. Lee Guan Par [2003] 7 MLRH 732.

[63] I agree that it is trite that a partnership is not a legal entity in law but the law permits for the partnership to be sued in the name of the firm and for a judgment to be entered against the firm. The Partnership Act itself provides so. Section 25(1) of the Partnership Act provides that: "A writ of execution shall not issue against any partnership property except on a judgment against the firm." And, it cannot be gainsaid that to execute a judgment against the firm, one must first have a judgment against the firm.

[64] Section 12 of the Partnership Act itself expressly provides that the firm is liable to the same extent as the partner who has committed any wrongful act or omission. The provisions are reproduced hereunder:

"Where, by any wrongful act or omission of any partner acting in the ordinary course of the business of the firm or with the authority of his co-partners, loss or injury is caused to any person not being a partner in the firm, or any penalty is incurred, the firm is liable therefor to the same extent as the partner so acting or omitting to act."

[65] Wherefore, with respect, I agree with the reasoning and decision of His Lordship, Hishamudin Mohd Yunus J (later JCA) in Southern Empire Development Sdn Bhd v. Tetuan Shahinuddin & Ranjit & Ors (supra) who held as follows:

"[12] ....In my judgment, the liability of the firm /partnership is distinct and different from the liability of the firm's partners. It is true that a partnership, being not a human being but merely an artificial legal entity, on its own can do nothing. Thus on its own it can do no wrong. The partnership acts through its human agency - its partners. Every act or omissions of the partners directly pertaining to the partnership is in law deemed to be an act or an omission of the partnership. But be that as it may, in relation to partnerships, the law recognizes two types of liability:

(1) the liability of the partners; and

(2) the liability of the partnership.

[13] In my opinion, ss 11 and 19 are irrelevant because they are concerned with the liability of partners; whereas the actual issue in the present case concerns the liability of the firm or partnership. In this regard, there is another provision of the Partnership Act that we must turn to - a provision that mentions about the liability of the firm /partnership itself - and that is s 12. This provision reads:

....

[14] It is, however, true that before any liability can be attributed to a partnership, a wrongful act or wrongful omission (that relates directly to the partnership) must first be committed by a partner.

[15] Yet at the same time it is also pertinent to note that there is nothing in s 12 or, indeed, anywhere else in the Partnership Act that states that the liability of the firm incurred by reason of a wrongdoing of a partner ceases once the errant partner ceases to be a partner of the firm.

[16] In my view, by virtue of s 12 above, the liability of the firm is distinct from the liability of the partners."

[66] That a judgment can be entered against a firm is underscored by the Rules of Court 2012 which provides elaborate rules on how a firm can sue or be sued. A specific set of rules on partnership is prescribed under O 77 ROC carrying the sub-title "Partners" and which provides as follows:

"1. Action by and against firms within jurisdiction (O 77 r 1)

Subject to the provisions of any written law, any two or more persons claiming to be entitled, or alleged to be liable, as partners in respect of a cause of action and carrying on business within the jurisdiction may sue or be sued, in the name of the firm, if any, of which they were partners at the time when the cause of action accrued.

2. Disclosure of partners' names (O 77 r 2)

(1) Any defendant to an action brought by partners in the name of a firm may serve on the plaintiffs or their solicitor a notice requiring them or him forthwith to furnish the defendant with a written statement of the names and places of residence of all the persons who were partners in the firm at the time when the cause of action accrued and if the notice is not complied with the Court may order in Form 190 the plaintiffs or their solicitor to furnish the defendant with such a statement and to verify it on oath or otherwise as may be specified in the order, or may order that further proceedings in the action be stayed on such teRM s as the Court may direct.

(2) When the names of the partners have been declared in compliance with a notice or an order given or made under paragraph (1), the proceedings shall continue in the name of the firm but with the same consequences as would have ensued if the persons whose names have been so declared had been named as plaintiffs in the writ.

(3) Paragraph (1) shall have effect in relation to an action brought against partners in the name of a firm as it has effect in relation to an action brought by partners in the name of a firm but with the substitution, for references to the defendant and the plaintiffs, of references to the plaintiff and the defendants respectively, and with the omission of the words "or may order" to the end.

3. Service of writ (O 77 r 3)

(1) Where in accordance with r 1 partners are sued in the name of a firm, the writ may, except in the case mentioned in paragraph (2), be served:

(a) on any one or more of the partners; or

(b) at the principal place of business of the partnership within the jurisdiction, on any person having at the time of service the control or management of the partnership business there, and where service of the writ is effected in accordance with this paragraph, the writ shall be deemed to have been duly served on the firm, whether or not any member of the firm is out of the jurisdiction.

(2) Where a partnership has, to the knowledge of the plaintiff, been dissolved before an action against the firm is begun, the writ by which the action is begun must be served on every person within the jurisdiction sought to be made liable in the action.

(3) Every person on whom a writ is served under paragraph (1) must at the time of service, be given a written notice in Form 191 stating whether he is served as a partner or as a person having control or management of the partnership business or both as a partner and as such a person, and any person on whom a writ is so served but to whom no such notice is given shall be deemed to be served as a partner.

4. Entry of appearance in an action against firm (O 77 r 4)

(1) Where persons are sued as partners in the name of their firm, appearance may not be entered in the name of the firm but only by the partners thereof in their own names, but the action shall nevertheless continue in the name of the firm.

(2) Where in an action against a firm the writ by which the action is begun is served on a person as a partner, that person, if he denies that he was a partner or liable as such at any material time, may enter an appearance in the action and state in the memorandum of appearance that he does so as a person served as a partner in the defendant firm but who denies that he was a partner at any material time. An appearance entered in accordance with this paragraph shall, unless and until it is set aside, be treated as an appearance for the defendant firm.

(3) Where an appearance has been entered for a defendant in accordance with paragraph (2):

(a) the plaintiff may either apply to the Court to set it aside on the ground that the defendant was a partner or liable as such at a material time or may leave that question to be deteRM ined at a later stage of the proceedings;

(b) the defendant may either apply to the Court to set aside the service of the writ on him on the ground that he was not a partner or liable as such at a material time or may at the proper time serve a defence on the plaintiff denying in respect of the plaintiff's claim either his liability as a partner or the liability of the defendant firm or both.

(4) The Court may at any stage of the proceedings in an action in which a defendant has entered an appearance in accordance with paragraph (2), on the application of the plaintiff or of that defendant order that any question as to the liability of that defendant or as to the liability of the defendant firm be tried in such manner and at such time as the Court directs.

(5) Where in an action against a firm the writ by which the action is begun is served on a person as a person having the control or management of the partnership business, that person may not enter an appearance in the action unless he is a member of the firm sued.

5. Enforcing judgment or order against the firm (O 77 r 5)

(1) Where a judgment is given or an order is made against a firm, execution to enforce the judgment or order may, subject to r 6, issue against any property of the firm within the jurisdiction.

(2) Where a judgment is given or an order is made against a firm, execution to enforce the judgment or order may, subject to r 6 and to the next following paragraph, issue against any person who:

(a) entered an appearance in the action as a partner;

(b) having been served as a partner with the writ, failed to enter an appearance in the action;

(c) admitted in his pleading that he is a partner; or

(d) was adjudged to be a partner.

(3) Execution to enforce a judgment or an order given or made against a firm may not issue against a member of the firm who was out of the jurisdiction when the writ was issued unless he-

(a) entered an appearance in the action as a partner;

(b) was served within the jurisdiction with the writ as a partner; or

(c) was, with the leave of the Court given under O 11, served out of the jurisdiction with the notice of the writ, as a partner,

and, except as provided by paragraph (1) and by the foregoing provisions of this paragraph, a judgment or order given or made against a firm shall not render liable, release or otherwise affect a member of the firm who was out of the jurisdiction when the writ was issued.

(4) Where a party who has obtained a judgment or an order against a firm claims that a person is liable to satisfy the judgment or order as being a member of the firm, and the foregoing provisions of this rule do not apply in relation to that person, that party may apply to the Court for leave to issue execution against that person, the application to be made by notice of application which must be served personally on that person.

(5) Where the person against whom an application under paragraph (4) is made does not dispute his liability, the Court hearing the application may, subject to paragraph (3), give leave to issue execution against that person and, where that person disputes his liability, the Court may order that the liability of that person be tried and deteRM ined in any manner in which any issue or question in an action may be tried and deteRM ined.

6. Enforcing judgment or order in action between partners (O 77 r 6)

(1) Execution to enforce a judgment or an order given or made in-

(a) an action by or against a firm in the name of the firm, against or by a member of the firm ; or

(b) an action by a firm in the name of the firm against a firm in the name of the firm where those firms have one or more members in common, shall not be issued except with the leave of the Court.

(2) The Court hearing an application under this rule may give such directions including directions as to the taking of accounts and the making of inquiries as may be just.

7. Attachment of debts owed by firm (O 77 r 7)

(1) An order may be made under O 49 r 1 in relation to debts due or accruing due from a firm carrying on business within the jurisdiction notwithstanding that one or more members of the firm is resident out of the jurisdiction.

(2) An order to show cause under r 1 relating to such debts as aforesaid must be served on a member of the firm within the jurisdiction or on some other person having the control or management of the partnership business.

(3) Where an order made under r 1 requires a firm to appear before the Court, an appearance by a member of the firm shall constitute a sufficient compliance with the order.

8. Actions begun by originating summons (O 77 r 8)

Rules 2 to 7 shall, with the necessary modifications, apply in relation to an action by or against partners in the name of their firm begun by originating summons as they apply in relation to such action begun by writ.

9. Application to person carrying on business in another name (O 77 r 9)

An individual carrying on business within the jurisdiction in a name or style other than his own name may be sued in that name or style as if it were the name of a firm, and rr 2 to 8 shall, so far as applicable, apply as if he were a partner and the name in which he carries on business were the name of his firm.

10. Applications for orders charging partner's interest in partnership property (O 77 r 10)

(1) Every application to the Court by a judgment creditor of a partner of an order under s 25 of the Partnership Act 1961 [Act 135] (which authorizes the High Court or a Judge thereof to make certain orders on the application of a judgment creditor of a partner including an order charging the partner's interest in the partnership property) and every application to the Court by a partner of the judgment debtor may in consequence of the first mentioned application must be made by notice of application.

(2) The Registrar may exercise the powers conferred on a Judge under s 25 of the Partnership Act 1961.

(3) Every notice of application issued by a judgment creditor under this rule and every order made on such notice of application, must be served on the judgment debtor and on such of his partners as are within the jurisdiction.

(4) Every notice of application issued by a partner of a judgment debtor under this rule and every order made on such notice of application, must be served:

(a) on the judgment creditor;

(b) on the judgment debtor; and

(c) on such of the other partners of the judgment debtor who do not join in the application and are within the jurisdiction.

(5) A notice of application or an order served in accordance with this rule on some of the partners of a partnership shall be deemed to have been served on all the partners of that partnership."

[67] For the following reasons, I am of the considered view that a judgment can be entered against a defendant who is sued in the name of the firm:

(i) the Partnership Act recognizes that property of a partnership can be held under the name of a partnership and it is described as partnership property, see ss 22 to 25. It is interesting to see that s 24 provides that "where land or any interest therein has become partnership property, it shall, unless the contrary intention appears, be treated as between the partners (including the representatives of a deceased partner), and also as between the heirs of a deceased partner and his executors or administrators, as personal and not real estate".

(ii) it is common for bank accounts of a firm to be opened in the name of the firm, just like in this case, where bank accounts of D5 and D6 were opened in their respective names (see the cheque in IDB B1 p 31 of a bank account under the name of (D5) Sharidan & Co's Office Acc, in IDB B50 at p 118 showing a bank-in deposit receipt of monies banked into the account of Sharidan & Co. See also, the cheques in IDB B1 p 115, and IDTP (1) p 39 carrying details of a bank account with the name of Adzliana & Partners Client's Acc (D6);

(iii) execution proceedings by way of garnishee proceedings can be carried out to attach monies standing to the credit of the accounts opened in the name of a firm who is a judgment debtor, see O 77 r 7 ROC (supra) and O 49 ROC on Garnishee Proceedings; and

(iv) If any issue is taken as to which partner's money is being attached, there are elaborate rules in O 77 rr 2, 5 and 7 for this issue to be dealt with.

Whether D4 Who Is A Salaried Partner Of D6 Is A Partner Of D6

[68] D4 joined D6 as a salaried partner on 19 January 2017 drawing a monthly salary of RM2,500.00 equivalent to the market salary of a first-year legal assistant in Seberang Perai Selatan, Penang.

[69] In the main, she asserts that the facts giving rise to the plaintiff's claim arose before she became a salaried partner of D6 and therefore she should not be liable. D4 contends that D2 and D3 were the only partners of D6 who had conduct of the files pertaining to the Project with her having no involvement.

[70] She further asserted that by the time she joined D6, the monies said to have been collected by D2 through the law firms of D5 or D6 and yet to be paid over to the plaintiff were no longer in D6's bank account.