Federal Court, Putrajaya

Mary Lim Thiam Suan, Harmindar Singh Dhaliwal, Abu Bakar Jais FCJJ

[Civil Appeal Nos: 02(f)-60-10-2023(A) & 02(f)-61-10-2023(A)]

25 April 2024

Civil Procedure: Costs — Claims for "legal costs" — Whether "costs" as defined under O 59 r 1 Rules of Court 2012 distinct from damages — Whether costs recoverable as special damages in same proceedings between parties

Legal Profession: Costs — Claims for "legal costs" — Whether "costs" as defined under O 59 r 1 Rules of Court 2012 distinct from damages — Whether costs recoverable as special damages in same proceedings between parties

The parties in these appeals had quite a long and chequered litigation history between them spanning over 17 years. Ultimately, after succeeding in proving that the appellants had defrauded them into parting with their properties, the properties were returned to the respondents. Because the High Court had also ordered that the damages be assessed by the Registrar, the parties were back before the High Court. The High Court awarded a total sum of RM5,135,951.76 together with interest. A separate sum of RM50,000.00 was also allowed as costs for the assessment of damages. The appellants appealed and the Court of Appeal unanimously allowed the appeals in part. The awards on general, punitive and exemplary damages were halved. The total award of damages then stood at RM4,135,951.76. Of that, a sum of RM2,604,000.00 represented the respondents' claims for "legal costs". These costs included retainer and refresher fees incurred over the entire passage of the protracted litigation journey. The appellants were dissatisfied and sought leave to appeal to the Federal Court. Leave was granted to the appellants on the following two questions of law: (1) whether "costs" as defined under O 59 r 1 of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC") were distinct from damages; (i) following from the foregoing, were costs recoverable as special damages in the same proceedings between the parties? and (ii) whether legal fee a specie of special damages and thus claimable over and on top of costs? and (2) whether the Commonwealth authorities (relied on by the appellants) which had held that legal fees could not be recovered as damages should also be adopted as the law in Malaysia.

Held (allowing the appeals):

(1) The most startling error made by both Courts below was in the misapprehension of the orders pronounced by the High Court on 28 November 2012. The terms of those orders were of utmost importance as it determined the assessment itself, what its ambit or parameters were. The assessment that was required to be conducted was only in respect of determining the amount payable as special damages, general damages, punitive and exemplary damages. This was quite clear from the terms of the order of 28 November 2012. That was a matter of proof and in the event insufficient or no evidence was led to prove the damages in question, generally none would be awarded unless the Court saw fit to award nominal damages. That did not arise here. (paras 12-13)

(2) Costs incurred in prosecuting a claim could not be in itself a cause of action, whether in separate or the same proceedings. More so, in the circumstances of the present appeals where costs were claimed as special damages between the same parties in the same proceedings, when there was already a specific order on costs; and where the items claimed as costs or special damages were themselves claimable as costs. There was in place in the system of civil justice, a fairly elaborate costs regime. While the Courts on the one hand were conferred with discretion to award costs, there was, on the other hand, an extensive regime in the ROC to complement that exercise of discretion. The regime in O 59 dealt with a myriad of matters regarding costs, including what costs might be claimed, when costs were to be determined, and what factors or considerations should be weighed at the material time of award. Even the amounts were spelt out, in broad terms. This costs regime existed for a specific purpose: to regulate the award of costs, ensuring that there was, to a large extent, consistency and uniformity in the awards of costs. There was a balance of interests between the "winning" and "losing" parties so that access to justice remained a real and viable right. The term "costs" was not defined in the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 but it was defined in the ROC. Order 59 r 1 defined "costs" to "includes fees, charges, disbursements, expenses and remuneration". From the evidence led before the High Court, it was apparent that the respondents were claiming as special damages, fees, charges, disbursements, expenses and remuneration as well as the refresher and retainer fees that they had to pay their lawyers in maintaining the action against the appellants. There was no doubt that these claims fell well within the terms of the costs order of 28 November 2012 and it was not open to the respondents to ignore that order. These claims were also claimable as costs in O 59 and were thus not claimable as damages. (paras 24-26)

(3) Costs incurred in the same proceedings between the same parties also could not be claimed as special damages as a matter of principle and policy. The High Court had reasoned that because the appellants were liable for their fraudulent acts, they were liable for all damages since the general rule of remoteness and foreseeability did not apply. Legal fees and other expenses in litigating the action between the parties were said to be a specie of special damages and thus recoverable, and the Court of Appeal agreed with the High Court. This Court, however, disagreed. Damages were compensatory in nature awarded to compensate for loss sustained as a result of a civil wrong committed in breach of a duty of care. Whether such damages were recoverable or not was a matter of proof dependent on the evidence adduced at trial. In the event there was lack of proof, the award should be nil or nominal. Costs of litigation, on the other hand, were discretionary. Costs were "a sum of money which the Court orders one party to pay to another party in respect of the expense of litigation incurred.... Costs are distinct from damages". (paras 31-33)

(4) On principle and on policy, including social policy, the respondents were not entitled to claim as special damages, the legal charges, legal fees, legal costs or litigation costs in the same proceedings between the same parties. The two questions posed were answered in the appellants' favour. In line with the Commonwealth authorities cited and relied on by the appellants, costs were indeed distinct from damages. Costs, including legal costs, were not recoverable as special damages in the same proceedings between the same parties. (paras 55-56)

Case(s) referred to:

British Motor Trade Association v. Salvadori And Others [1949] CH 556 (refd)

Cockburn v. Edwards [1881] 18 Ch D 449 (folld)

Doyle v. Olby (Ironmongers) Ltd [1969] 2 All ER 119 (refd)

Gray v. Sirtex Medical Ltd [2011] 276 ALR 267 (folld)

Kembang Serantau Sdn Bhd v. YBK Usahasama Sdn Bhd [2020] 2 MLRA 679 (refd)

Larpin Christian Alfred & Another v. Kaikhushru Shiavax Nargolwala & Another [2022] SGHC (I) 12 (refd)

Ling Peek Hoe & Anor v. Ding Siew Ching & Ors [2017] 4 MLRA 372 (refd)

Maryani Sadeli v. Arjun Permanand Samtani And Another & Other Appeals [2015] 1 SLR 496 (folld)

MD Biomedical Engineering (M) Sdn Bhd v. Goh Yong Khai [2022] 4 MLRA 44 (refd)

Michael Vaz Lorrain v. Singapore Rifle Association [2021] 1 SLR 513 (refd)

Quartz Hill Gold Mining v. Eyre [1883] 11 QBD 674 (folld)

Ross v. Caunters (A firm) [1979] 3 All ER 580 (folld)

Rustem Magdeev v. Dimitry Tsvetkov & Others [2019] EWHC 1557 (refd)

Singapore Shooting Association & Others v. Singapore Rifle Association [2020] 1 SLR 395 (folld)

Sitti Rajumah & Anor v. Mohd Rafiuddin Elmin [1996] 2 MLRH 890 (refd)

Smith New Court Securities v. Scrimgeour Vickers (Asset Management) Ltd [1999] 4 All ER 769 (distd)

Sunseekers Pte Ltd v. JSH Joshua [1990] 5 MLRH 442 (refd)

Yap Boon Hwa v. Kee Wah Soong [2019] MLRAU 289 (distd)

Legislation referred to:

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, ss 25(2), 70, 96, 99, Sch item 15

Rules of Court 2012, O 37 r 6, O 59 rr 1, 2

Other(s) referred to:

Halsbury's Laws of England, 4th Reissue, Vol 12(1), p 266, para 807

Counsel:

For the appellants: Ranjit Singh (Saw Wei Siang & Yeoh Cho Kheong with him); M/s Nethi & Saw

For the respondents: Hong Chong Hang (Edmund Lim Yun with him); M/s Hong Chew King

JUDGMENT

Mary Lim Thiam Suan FCJ:

[1] The parties in these appeals unfortunately have quite a long chequered litigation history between them spanning over 17 years - see decision of the Federal Court in Ling Peek Hoe & Anor v. Ding Siew Ching & Another Appeal [2017] 4 MLRA 372 (Federal Court). Ultimately, after succeeding in proving that the appellants had defrauded them into parting with their properties, the properties were returned to the respondents. Because the High Court had also ordered that damages be assessed by the Registrar, the parties were back before the High Court on that assessment of damages. These appeals arise from the damages that were assessed.

[2] A substantial part of the damages awarded comprised legal charges (RM2,918,000.00) that the respondents claimed they had incurred in the course of litigation between the parties. It is these legal charges that the appellants were discontent with and which form the substratum of these appeals; whether such charges may be recovered as special damages in the same proceedings between the same parties.

Order Of The High Court Dated 28 November 2012

[3] In order to fully appreciate the issue on the legal charges, we must go back to what the respondents' claim was about and the original order made on 28 November 2012. In a nutshell, the respondents claimed that the appellants had wrongfully conspired and combined amongst themselves to defraud and injure them in relation to two of their properties. After a full trial, the High Court allowed the respondents' claim and on 28 November 2012, declared the transfer of the two properties to the appellants invalid, null and void. That same order also ordered damages to be paid to the respondents. The relevant parts of the order read as follows:

ADALAH DIHAKIMI bahawa perjanjian-perjanjian jualbeli antara plaintif pertama dengan defendan ketiga, keempat dan/atau kelima untuk GM 3896 (dahulu EMR 2358) Lot 2563 dan GM 3895 (dahulu EMR 2359) Lot 2564 kedua-dua Mukim Sitiawan adalah diisytiharkan batal dan tidak sah.

DAN ADALAH DIHAKIMI bahawa borang-borang pindahmilik untuk GM 3896 (dahulu EMR 2358) Lot 2563 dan GM 3895 (dahulu EMR 2359)

Lot 2564 kedua-dua Mukim Sitiawan dan PN 104828 Lot 34911 (dahulu HS (D) Dgs 5664 PT 17562) Mukim Sitiawan daripada plaintif pertama kepada defendan ketiga, keempat dan kelima adalah diisytiharkan batal dan tidak sah.

DAN ADALAH DIHAKIMI bahawa defendan-defendan membayar plaintifplaintif gantirugi khas, am, punitive dan teladan tertakluk kepada taksiran oleh Pendaftar.

DAN ADALAH DIHAKIMI bahawa tuntutan balas defendan ketiga, keempat dan kelima terhadap plaintif pertama adalah ditolak dengan kos.

DAN AKHIRNYA DIHAKIMI bahawa defendan-defendan membayar plaintif-plaintif faedah dan kos tindakan-tindakan ini untuk ditaksir oleh Pendaftar sekiranya tidak dipersetujui oleh plaintif-plaintif dan defendandefendan.

[4] This decision of the High Court was set aside by the Court of Appeal on 13 March 2015 but it was reinstated by the Federal Court on 20 June 2017. The appellants filed three separate applications to review the Federal Court's decision of 20 June 2017. All three failed. The last application was struck out with no liberty to file afresh on 27 May 2019.

Order Of the High Court dated 10 January 2022

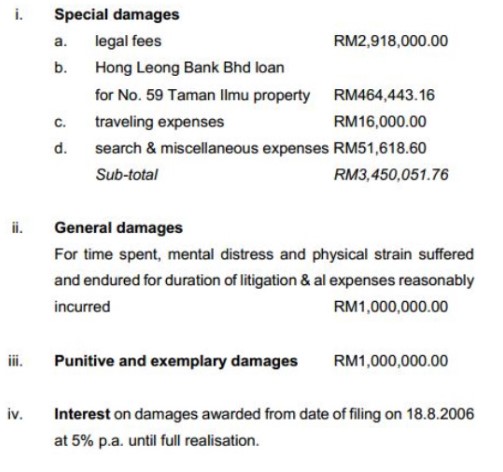

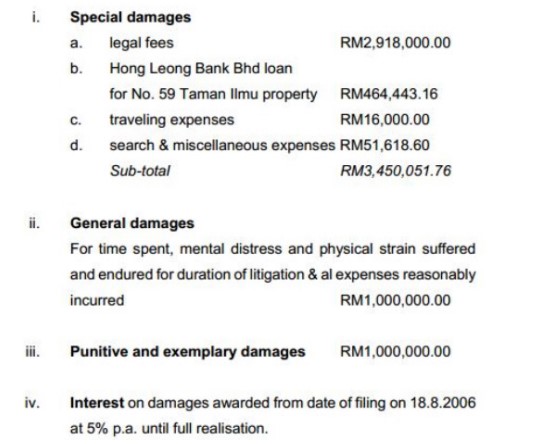

[5] After the two properties were returned to the respondents, what was outstanding was the assessment of damages and the matter of costs. The respondents took steps towards completion of that assessment. Their claims for special damages, general damages, punitive and exemplary damages are summarised as follows:

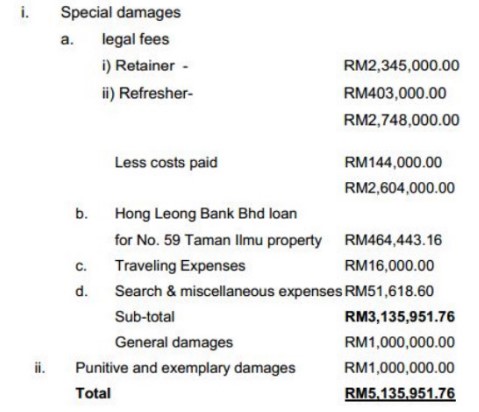

[6] Both sides called witnesses, a total of 10 in fact were called. On 10 January 2022, the assessment was finally completed and a total sum of RM5,135,951.76 was awarded together with interest. A separate sum of RM50,000.00 was also allowed as costs for the assessment of damages.

[7] The appellants appealed. On 18 April 2023, the Court of Appeal unanimously allowed the appeals in part. The awards on general damages, and punitive and exemplary damages were halved. The appellants were dissatisfied and sought leave to appeal to the Federal Court.

The Two Questions Of Law

[8] On 18 October 2023, leave was granted under s 96 of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (Act 91) on two questions of law, although a great many others were framed:

Question 1

Whether "costs" as defined under O 59 r 1 of the Rules of Court 2012 are distinct from damages?

i. Following from the foregoing, are costs recoverable as special damages in the same proceedings between the parties?

ii. Whether legal fee is a specie of special damages and thus claimable over and on top of costs?

Question 2

Whether the following Commonwealth authorities which have held that legal fees cannot be recovered as damages should also be adopted as the law in Malaysia?

i. Cockburn v. Edwards [1881] 18 Ch D 449

ii. Quartz Hill Gold Mining v. Eyre [1883] 11 QBD 674

iii. Ross v. Caunters (A Firm) [1979] 3 All ER 580

iv. Gray v. Sirtex Medical Ltd [2011] 276 ALR 267

v. Maryani Sadeli v. Arjun Permanand Samtani And Another & Other Appeals [2015] 1 SLR 496

vi. Singapore Shooting Association & Others v. Singapore Rifle Association [2020] 1 SLR 395

Our Decision

[9] The total award of damages now stands at RM4,135,951.76. Of that, a sum of RM2,604,000.00 represents the respondents' claims for "legal charges", sometimes referred to as "legal costs" or "legal fees". These charges, fees or costs include retainer and refresher fees incurred over the entire passage of the protracted litigation journey.

[10] But, before we deal with the questions posed, we pause to remind that unless specifically ordered by the trial judge before the start of proceedings or unless there is consent between the parties, a trial judge must always run the trial in its entirety and not leave some part of the decision-making to another occasion; or worse, to another person such as the Registrar in this case. Serious jurisdictional issues may arise in such a situation. Parties may also have already led evidence on both issues of liability and quantum; or in some cases, the issue of damage is intrinsic or necessary towards proving the cause of action. One such example would be the tort of defamation.

[11] The bifurcation of the conduct of any trial should only be carried out in the most necessary and appropriate cases. Courts should avoid conducting trials in truncated fashion or instalments as it frequently leads to a waste of valuable resources and time, unnecessarily prolonging time spent in Court in the final analysis. Sometimes, the earlier pronouncements or orders are not properly understood or appreciated leading to unnecessary and convoluted litigation. These appeals are clear illustrations of what can go quite wrong.

[12] Returning to the questions posed, we noticed that the most startling error made by both Courts below is in the misapprehension of the orders pronounced by the High Court on 28 November 2012. The terms of those orders are of utmost importance as it determines the assessment itself, what its ambit or parameters are. Lest we ourselves forget what those orders were, they are as follows:

DAN ADALAH DIHAKIMI bahawa defendan-defendan membayar plaintifplaintif gantirugi khas, am, punitive dan teladan tertakluk kepada taksiran oleh Pendaftar.

[13] The assessment that was required to be conducted was only in respect of determining the amount payable as special damages, general damages, punitive and exemplary damages. This is quite clear from the terms of the order of 28 November 2012. That is a matter of proof and in the event insufficient or no evidence is led to prove the damages in question, generally none would be awarded unless the Court sees fit to award nominal damages. That did not arise here.

[14] The respondents' claims for special damages, general damages, punitive and exemplary damages are summarised as follows:

[15] After hearing evidence, the High Court awarded a sum of RM5,135,951.76 comprising the following:

[16] On appeal, a substantial part of the above award was maintained although the award for general damages, and punitive and exemplary damages was halved by the Court of Appeal. The award now stands at RM4,135,951.76, comprising a sum of RM2,604,000.00, being costs incurred in prosecuting the whole action from the High Court to the Federal Court over the years, and now awarded as part of special damages.

[17] In our unanimous view, such award on the costs is manifestly wrong for two principal reasons.

[18] First, the matter of costs was already settled at the High Court back on 28 November 2012. The High Court had, in exercise of its discretion under s 25(2) read with item 15 in the Schedule to the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (Act 91) on the Additional Powers of the High Court, awarded costs to the respondents. The High Court had further directed its mind on how the costs was to be resolved, that the parties had a chance to settle it amicably but if they were unsuccessful, the costs would be taxed by the Registrar. This is clear from the terms of the order dated 28 November 2012:

DAN AKHIRNYA DIHAKIMI bahawa defendan-defendan membayar plaintif-plaintif faedah dan kos tindakan-tindakan ini untuk ditaksir oleh Pendaftar sekiranya tidak dipersetujui oleh plaintif-plaintif dan defendandefendan.

[Emphasis Added]

[19] These terms directed the appellants to pay the respondents costs of the action and that such costs were to be taxed by the Registrar if not agreed between the parties.

[20] The award of costs is a matter of discretion; quite different from an award of damages as damage is one of the elements that must be proved in order to succeed in a claim, be it in tort or contract. This power to award costs is specifically provided for in the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (Act 91); namely ss 25(2), 70 and 99.

[21] While s 25(2) read with item 15 in the Schedule to the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 (Act 91) on the Additional Powers of the High Court confers power on the High Court to award costs, ss 70 and 99 confer power to the Court of Appeal and Federal Court respectively to award costs but these powers differ from those of the High Court. By s 70, the Court of Appeal is empowered to "make such order as to the whole or any part of the costs of appeal or in the court below as is just". Similarly, s 99 confers discretion on the Federal Court to deal with the costs of the appeal:

Costs

99. (1) The costs incurred in the prosecution of any appeal or application for leave to appeal under this Part shall be paid by such party or parties, person or persons as the Federal Court may by order direct and the amount of any such costs shall be taxed by the Chief Registrar of the Federal Court in accordance with the rules of court.

(2) The Federal Court may make such order as to the whole or any part of the costs in the Federal Court, or in the Court of Appeal or in the High Court as is just.

[22] Both the Federal Court and Court of Appeal's powers to award costs extend to dealing with costs other than those incurred in their respective Court. The High Court does not have such power as apparent from a reading of s 25(2) and item 15 of the Schedule to Act 91. The power of the High Court to award costs is necessarily of and in relation to proceedings at the High Court alone. In these appeals, the costs claimed by the respondents and which was assessed and then awarded by the High Court as part of special damages included costs at the Court of Appeal and Federal Court.

[23] It is clear that such award faces serious jurisdictional constraints aside from the fact that at the time of the order, costs at the Court of Appeal and Federal Court were non-existent and entirely speculative. This, too appears to have escaped the attention of the Courts below although the High Court seemed to have treated O 37 r 6 of the Rules of Court 2012 as entitling the respondents to such costs as a "continuing cause of action" thereby conferring jurisdiction on the High Court to award costs subsequent to the order that granted the costs.

[24] With respect, we disagree. Costs incurred in prosecuting a claim cannot be in itself a cause of action, whether in separate or the same proceedings. More so, in the circumstances of the present appeals where costs were claimed as special damages between the same parties in the same proceedings, when there was already a specific order on costs; and where the items claimed as costs or special damages were themselves claimable as costs.

[25] There is in place in our system of civil justice a fairly elaborate costs regime. While the Courts on the one hand are conferred with discretion to award costs, there is, on the other hand, an extensive regime in the Rules of Court 2012 to complement that exercise of discretion. The regime in O 59 deals with a myriad of matters regarding costs including what costs may be claimed, when costs are to be determined, and what factors or considerations should weigh at the material time of award. Even the amounts are spelt out, in broad terms. This costs regime is there for a purpose: to regulate the award of costs, ensuring that there is to a large extent, consistency and uniformity in the awards of costs. There is a balance of interests between the "winning" and the "losing" parties so that access to justice remains a real and viable right.

[26] The term "costs" is not defined in Act 91 but it is defined in the Rules of Court 2012. Order 59 r 1 defines "costs" "includes fees, charges, disbursements, expenses and remuneration". From the evidence led before the High Court, it is apparent that the respondents were claiming as special damages, fees, charges, disbursements, expenses and remuneration as well as the refresher and retainer fees that they had to pay their lawyers in maintaining the action against the appellants. We are in no doubt that these claims fall well within the terms of the costs order of 28 November 2012 and it was not open to the respondents to ignore that order. These claims were also claimable as costs in O 59 and were thus not claimable as damages.

[27] We understand that the costs ordered payable to the respondents were not agreed between the parties and the respondents did not proceed to prepare a bill of taxation for the party and party costs to be taxed, as ordered. At the time the order for costs to be taxed was made, the Rules of Court 2012 had already come into force. It came into force on 1 August 2012. Arguably, the Rules of the High Court 1980, where there are extensive provisions for the taxation of costs, will no longer apply.

[28] However, the respondents did not seek any clarification or take steps under O 59. Instead, the respondents unilaterally decided to claim these costs of the action together with other costs incurred at the Court of Appeal and Federal Court as part of their special damages. For the reasons already explained, this option was not available to the respondents.

[29] The claim for such costs was also on a full indemnity basis. This was allowed by the High Court and affirmed on appeal.

[30] Again, we disagree. It was not open to the High Court to assess costs on a full indemnity basis. Costs are generally awarded on a party and party basis. If it was to be on any other basis, say indemnity or solicitor and client basis, then a specific order has to be sought. There are none from the terms of the order of 28 November 2012. In the absence of a specific order to the contrary, then the costs must be assessed on a party and party basis.

[31] The second principal reason why the costs incurred in the same proceedings between the same parties cannot be claimed as special damages is a matter of principle and policy. We have actually already alluded to some aspect of that principle and policy when discussing O 59 of the Rules of Court 2012.

[32] The High Court had reasoned that because the respondents were liable for their fraudulent acts, following Doyle v. Olby (Ironmongers) Ltd [1969] 2 All ER 119, Smith New Court Securities v. Scrimgeour Vickers (Asset Management) Ltd [1999] 4 All ER 769, Yap Boon Hwa v. Kee Wah Soong [2019] MLRAU 289 and MD Biomedical Engineering (M) Sdn Bhd v. Goh Yong Khai [2022] 4 MLRA 44, the appellants were liable for all damages since the general rule of remoteness and foreseeability did not apply. Legal fees and other expenses in litigating the action between the parties were said to be a specie of special damages and thus recoverable. The Court of Appeal agreed.

[33] We disagree. Damages are compensatory in nature awarded to compensate for loss sustained as a result of a civil wrong committed in breach of a duty of care. Whether such damages are recoverable or not is a matter of proof dependent on the evidence adduced at trial. As mentioned earlier, in the event there is lack of proof, the award should be nil or nominal. Costs of litigation on the other hand are discretionary. Costs are "a sum of money which the Court orders one party to pay to another party in respect of the expense of litigation incurred... Costs are distinct from damages" (see Halsbury's Laws of England, 4th Reissue, Vol 12(1) p 266 para 807). Order 59 r 2 of the Rules of Court 2012 have also provided:

(2) Subject to the express provisions of any written law and of these Rules, the costs of and incidental to proceedings in the Court, shall be in the discretion of the Court, and the Court shall have full power to determine by whom and to what extent the costs are to be paid.

[34] The appreciation of what costs represent in the whole scheme of litigation, we need to start with the old case of Cockburn v. Edwards [1881] 18 Ch D 449. While the circumstances under which the views and principles have evolved may be quite different from those presented in the instant appeals, it goes without saying that it is the principles that we are concerned with.

[35] In Cockburn v. Edwards, the plaintiff had sued his solicitors for breach of duty in relation to the preparation of a sales and purchase agreement where the solicitor himself had lent the plaintiff, his client, part of the money for a second mortgage, and had claimed inter alia for costs as between solicitor and client of the litigation in which the damages were recovered. All three judges declined to recognise such a right of claim. In Jessel MR's view:

"The most important point is as to the costs as between solicitor and client. I am of the opinion that it is not according to law to give to a party by way of damages the costs as between solicitor and client of the litigation in which the damages are recovered. The law gives a successful litigant his costs as between party and party, and he cannot be said to sustain damage by not getting them as between solicitor and client."

Brett LJ opined:

"As to the extra costs, the damages in an action of tort must have been incurred when the action is brought, except in some cases where they include everything up to the time of trial, and they cannot include any expenses incurred in the action itself. The law considers the extra costs which are disallowed on taxation between party and party as a luxury for which the other party ought in no case to be liable, and they cannot be allowed by way of damages."

Cotton LJ similarly said:

"Now, first, I am of the opinion that the difference between solicitor and client costs and party and party costs in an action cannot be given by way of damages in the same action, the latter costs being all the plaintiff is entitled to. Costs in another action stand on quite a different footing."

[36] Brett LJ repeated his views in Quartz Hill Gold Mining v. Eyre [1883] 11 QBD 674, that "extra costs", that is, the difference between the amount a successful litigant is required to pay his solicitors and his party and party costs, are not damages for which an action can lie. As we understand the practice, the scale of party and party costs were generally assessed on a two-third of the solicitor and client costs scale. The effect of these decisions is that a successful claimant is not entitled to claim that one-third difference from the other party. In the event that is intended, an indemnity scale or basis ought to have been sought from the Court at the material time. Otherwise it would either be too late or disallowed as a matter of principle.

[37] The decision of Ross v. Caunters (A Firm) [1979] 3 All ER 580 is frequently cited for the principle of duty of care that a solicitor owes in relation to his professional work, that such a duty is not restricted to his immediate client but may extend to others where a prima facie duty of care towards such persons can be shown. In these appeals, this decision is relied on by the appellants for the proposition that costs are not recoverable as part of damages.

[38] In Ross v. Caunters, Megarry VC was unequivocal on the principle that costs are not claimable as damages:

"It also seems to me that there is ample authority for saying that a successful plaintiff cannot obtain, in the guise of damages, any costs which, on a party and party taxation of costs, are disallowed by the taxing master. It is not enough for the plaintiff to claim that such costs were incurred by him as a result of the defendant's negligence. I think that this is sufficiently established by Cockburn v. Edwards. I am saying nothing about damages which fall outside the particular form in which they are claimed in this case, namely, the legal expenses of investigating the plaintiff's claim up to the date of issue of the writ. It seems to be that both on authority and on principle those legal expenses can be recovered by the plaintiff only as costs, and not in the form of damages. In so far as the plaintiff can persuade the taxing master that the items incurred should be allowed as costs on a party and party taxation, the plaintiff can recover them; but so far as they are not allowed by the taxing master, then I think that they cannot be recovered in the shape of damages."

[39] The practice in Australia is no different. In Gray v. Sirtex Medical Ltd [2011] 276 ALR 267, the Federal Court of Australia recognised the above general principle, that:

[15] A distinction has long been drawn between damages and legal costs, such that a successful plaintiff cannot recover its costs of the proceedings from the defendant as damages, even though the defendant's wrongful act caused the plaintiff to incur those costs: Cockburn v. Edwards [1881] 18 Ch D 449 (Cockburn) per Jessel MR at 459, per Brett LJ at 462 and per Cotton LJ at 463; Ross v. Caunters [1980] CH 297 at 342E-G; [1979] 3 All ER 580 at 601; Hobartville Stud Pty Ltd v. Union Insurance Co Ltd (1991) 25 NSWLR 358 at 356F-366B; Seavision Investments SA v. Evennett & Clarkson Puckle Ltd (The "Tiburon") [1992] 2 Lloyd's Rep 26 at 34; Queanbeyan Leagues Club Ltd v. Poldune Pty Ltd [2000] NSWSC 1100 at [45] and [46] (Quenbeyan Leagues Club); McGregor on Damages, 18th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, London, 2009, at [17-003]. A plaintiff's ability to recover its costs of the proceedings from a defendant depends instead upon the exercise of a judicial discretion; and the amount (if any) that the plaintiff recovers is not assessed in the same way as damages, but "taxed" according to the applicable rules of court. As Jessel MR put it in Cockburn at 459.8:

... it is not according to law to give to a party by way of damages the costs as between solicitors and client of the litigation in which the damages are recovered. The law gives a successful litigant his costs as between party and party, and he cannot be said to sustain damage by not getting them as between solicitor and client.

[16] Neither may a successful plaintiff or defendant recover the difference between the legal costs awarded in its favour, or withheld, as the case may be, in one civil proceeding and the legal costs it actually incurred in that proceeding, as damages in a subsequent civil action against the same opponent: Anderson v. Bowles (1951) 84 CLR 310 at 323.4-8 and 324.2; [1951] ALR 913; Quartz Hill Consolidated Gold Mining Co v. Eyre (1883) 11 QBD 674 at 690.4-5; Barnett v. Corporation of Eccles [1900] 2 QB at 427.8 and 428.5; Ritchie v. British Insulated Callender's Cables (Aust) Pty Ltd (1960) 77 WN(NSW) 299 at 300.4-10 (RHC); Berry v. British Transport Commission [1962] 1 QB 36 at 317.1. 319.2-4, 320.9- 321.4, 322.1, 329.6, 329.7-330.1, 336.4 and 336.7-9; [1961] 3 All ER 65 (Berry); Lonrho PLC v. Fayed (No 5) [1993] 1 WLR 1489 at 1497G-H, 1505G-H and 1510D-F; [1994] 1 All ER 188 (Lonrho); Penn v. Bristol & West Buildings Society [1997] 1 WLR 1356 at 1364H; [1997] 3 All ER 470 (Penn); Avenhouse v. Hornsby Shire Council (1998) 44 NSWLR 1 at 36G-37C; Queanbeyan Leagues Club at [45] and [46]; Grainger v. Williams [2009] WASCA 60 at [104] and [203]. Whether and to what extent a party is entitled to recover its costs from the opponent is regarded as having been finally determined in the first proceeding. Otherwise, most successful plaintiffs could bring a second action against the defendant to recover the costs they failed to obtain upon taxation as damages flowing from the original wrong; Berry at 32.5-6 and 328.2.

[17] As Scott stated in Seavision Investment SA v. Norman Thomas Evennett and Clarkson Puckle Ltd (The "Tiburon') [1992] 2 Lloyd's Rep 26 at 32.24-52 (RHC):

It is often the case that the costs of litigation would, if ordinary principles governing the recoverability of damages were applicable, represent recoverable damages. This is so not only in contract cases but also in tort cases. If A sues B on a negligence claim, whether in contract or in tort, the incurring by A of the costs of and incidental to the action will often, perhaps usually, be a foreseeable consequence of the negligent act. But it is, I believe, well settled that the recovery by A from B must be by way of an order for costs made in exercise of the s 51(1) discretionary power.

[40] The Federal Court of Australia however, allowed costs to be recovered as damages since the claim brought through a cross-claim was made against a third party. Such claims are treated as separate third-party proceedings in which case, the claim was allowed.

[41] Be that as it may, the Federal Court of Australia recognised that costs cannot be recovered as damages because costs are subject to judicial discretion whereas damages are a matter of proof and assessment. Also, the question of entitlement and amount of costs are completely determined in the first or original proceedings. Otherwise, successful plaintiffs may bring a second action just to recover any costs that may not have been fully allowed or where a successful plaintiff had overlooked asking for indemnity costs and was awarded party and party costs

[42] While the remarks were made in the context of negligence or contractual claims, and the present claims were founded in fraud, this principle remains the same. Although the general rule on remoteness and foreseeability are not applicable when it comes to fraud, it does not mean that costs of litigation transcend into damages.

[43] The Courts in Singapore follow Cockburn v. Edwards as evident from the decisions in Maryani Sadeli v. Arjun Permanand Samtani And Another & Other Appeals [2015] 1 SLR 496 and Singapore Shooting Association & Others v. Singapore Rifle Association [2020] 1 SLR 395.

[44] In Maryani Sadeli, the Singapore Court of Appeal went further to disallow a claim for unrecovered costs of the previous legal proceedings sought through a second set of proceedings between the parties, albeit in different capacities. Effectively, it was a claim for a full indemnity of the previous legal costs incurred in earlier legal proceedings between the same parties. In upholding the decision of the High Court which had dismissed the claim both on the law and on the facts, the Court of Appeal held as follows:

[20] The general rule on the recovery of costs of previous legal proceedings as damages in subsequent proceedings is clear: such costs which were unrecovered previously cannot be recovered in a subsequent claim for damages, at least in so far as it involved a same-party case.

[21] Whatever costs that a party seeks to recover should be dealt with in those same proceedings for which the costs were incurred, and the incidence of unrecovered costs cannot thereafter be the subject subsequent legal action. As Bowen LJ observed in the English Court of Appeal decision of The Quartz Hill Consolidated Gold Mining Company v. Eyre (1883) 11 QBD 674 (at 690):

... The bringing of an ordinary action does not as a natural or necessary consequence involved any injury to a man's property, for this reason, that the only costs which the law recognises, and for which it will compensate him, are the costs properly incurred in the action itself. For those the successful defendant will have been already compensated, so far as the law chooses to compensate him. if the judge refuses to give him costs, it is because he does not deserve them: if he deserved them, he will get them in the original action: if he does not deserve them, he ought not to get them in a subsequent action...

[45] The Court of Appeal noted that the legal basis for disallowing such claims was posited in public policy, more specifically social policy of bringing down costs of litigation and encouraging finality of litigation whilst enhancing access to justice. According to the Court of Appeal:

29. The starting point must be to appreciate that in all manner of litigation, legal costs are an inevitable expense to both the party bringing the action and the party defending it. It is therefore impossible, at least from a practical standpoint, for an individual's general right of access to the law to be divorced from the rules and principles governing the costs of litigation. In this regard, a legal system's rules on costs (which include how legal costs should be recovered in litigation) are necessarily a matter of social policy. This is underscored by the numerous reports commissioned by Governments around the world which studied the rules and principles governing the costs of litigation as part of a wider review of civil justice...

[46] The Court of Appeal further noted that a "fundamental aspect of our scheme of costs recovery is a cost-shifting rule which dictated that the successful litigant is ordinarily indemnified by the losing party for the legal costs incurred as between the successful party and his solicitor. This is commonly referred to as the principle that costs should generally follow the event, and is also known as the indemnity principle (although it should be noted that the term "indemnity principle" is also confusingly used to refer to the principle that prevents a party from recovering more by way of costs from an opponent than he is obliged to pay to his own lawyers (see the Jackson Report at p 53)).

31. The indemnity principle, however, does not result in an indemnity in the full or literal sense. The legal costs recoverable by the successful party from the losing party are more often than not less than the actual legal fees incurred as between the successful party and his solicitor. This is because the indemnity principle is also subject to a series of rules governing how recovery of costs is quantified, and those rules operate such that a full indemnity for legal costs is only recoverable by parties to litigation in exceptional circumstances (for example, where there is a contractual agreement between the parties to this effect).

34. Ultimately, our legal regime on costs recovery is calibrated in a manner such that full recovery of legal costs by the successful party is the exception rather than the norm. What we need to bear in mind is that this state of affairs is not something which exists to prejudice the winning party in litigation, but is a manifestation of the law's policy of enhancing access to justice for all. Put another way, unrecovered legal costs is something which is part and parcel of resolving disputes by seeking recourse to our legal system and all parties who come before our Courts must accept this to be a necessary incidence of using the litigation process. It is in this light that the general rule must be understood.

[47] Those views were expressed in the context of subsequent action for unrecovered legal costs from an earlier action between the same parties; and we find no reason to disagree. In the context of our present appeals, the social policy reasons will be even more compelling as not only is the claim for costs between the same parties, the claim made under cover of special damages arise in the same proceedings. Such costs are necessarily costs of litigation which any party seeking recourse through our legal system must bear and thus accept as "necessary incidence of using the litigation process".

[48] In the more recent decision of Singapore Shooting Association & Others v. Singapore Rifle Association, the Singapore Court of Appeal had occasion to examine the issue of whether investigation costs and solicitor's fees can constitute actionable loss or damage in the tort of conspiracy if such costs cannot be recovered as part of the costs of the action. After examining the position in the UK (British Motor Trade Association v. Salvadori And Others [1949] CH 556; and Rustem Magdeev v. Dimitry Tsvetkov & Others [2019] EWHC 1557 (Comm) in particular), the Court of Appeal held:

92. .... the legal fees incurred in investigating, detecting, unravelling and/or mitigating a conspiracy cannot constitute actionable loss or damage in the tort of unlawful means conspiracy if they are in substance the sort of expenses that would be incurred in preparation for litigation, and so would be recoverable as costs in any action that may be brought.

93. There are three reasons for such a rule. The first is that if legal fees that can be recovered as costs were held to be sufficient to constitute actionable loss or damage in the tort of conspiracy, then, as we pointed out to Mr Wong at the hearing, the result would be that this element of the tort would be satisfied in virtually every case where the litigant pleading conspiracy engages a lawyer. A litigant who mounts a claim in conspiracy and who engages lawyers to assist him in doing so, as will almost invariably be the case, could simply assert that his legal fees were incurred in investigating and/or mitigating the conspiracy so as to establish the loss/damage element of the tort. Costs would simply be characterised as damages. We consider that this too readily dilutes the requirement that a claimant who brings an action in the tort of conspiracy must prove that he has suffered loss or damage as a result of the conspiracy.

94. Our second reason is that allowing solicitor's fees that are recoverable as costs to be recovered as damages instead would subvert the costs regime put in place to regulate the recoverability of such fees. We observed in Maryani Sadeli v. Arjun Permanand Samtani And Another & Other Appeals [2015] 1 SLR 496 that a legal system's rules on costs (which include how legal costs should be recovered in litigation) are necessarily a matter of social policy: at [29] and [33]. This includes the important policy of "enhancing access to justice for all"...The application of such principles involves a different assessment, and will likely lead to a different result, from that involved in an inquiry into damages, which is instead subject to rules of causation, remoteness and mitigation: see Louise Merrett, "Costs As Damages" (2009) 125 LQR 468 at 470...

95. ....

96. The third reason for the general rule is that there is simply no authority in support of SRA's contention that the legal fees incurred for the purposes of investigating a conspiracy can constitute actionable loss or damage in the tort of conspiracy...

97. ...the rule as we have framed it at [92] above does envisage that such fees may constitute actionable loss or damage if, for some reason, they cannot be recovered as costs instead. In our judgment, this proviso flows naturally from the second reason set out at [94] above because if such fees cannot be recovered as costs, then the costs regime would not be subverted by their being claimed as damages instead...

[49] These decisions have since been consistently followed in Singapore - see Michael Vaz Lorrain v. Singapore Rifle Association [2021] 1 SLR 513 (where the Court was of the view that the principle applied regardless of the type of claim) and Larpin Christian Alfred & Another v. Kaikhushru Shiavax Nargolwala & Another [2022] SGHC (I) 12.

[50] We find the three reasons articulated in Singapore Shooting Association to be strongly persuasive. There is a clear costs regime in O 59 of the Rules of Court 2012 and it would be equally true to say that the principles applicable when exercising discretion whether to grant costs, and the extent of such costs, have taken numerous factors into consideration. As a matter of law, the legal fees, charges, retainer, refresher or any other charges associated with the litigation between the parties at the High Court (and likewise at the Federal Court and Court of Appeal) are not claimable as damages. These sums are only claimable as costs within the costs regime as provided in O 59.

[51] Finally, the decisions of Yap Boon Hwa (supra) and Smith New Court Securities v. Scrimgeour Vickers (Asset Management) Ltd [1999] 4 All ER 769. In Yap Boon Hwa, the Court of Appeal awarded legal fees incurred by the defendant in defending the action of fraudulent misrepresentation whilst in Smith New Court Securities, the Court once again reaffirmed the principle in Doyle, that damages are not subject to the rules of remoteness in a claim founded on the tort of deceit. A successful plaintiff is entitled to recover by way of damages the full price paid, the plaintiff must give credit for any benefits received as a result of the transaction. In Smith, the plaintiff claimed that he had been fraudulently induced to purchase certain property by the defendant. Neither Yap Boon Hwa nor Smith is authority for the proposition that costs in the proceedings which are otherwise only recoverable through the costs regime and subject to the discretion of the Court, are recoverable as damages. There were no claims for legal fees, charges or costs, whether in the original action or any subsequent action.

[52] Thus, we do not find these authorities to be of any relevance or assistance since there were no discussions on the matter of whether legal fees were barred by reason of the fee regime and other policy considerations, as discussed above. At para [77], the Court of Appeal held that there was "sufficient reason in respect of legal fees incurred by the defendant in defending the action of fraudulent misrepresentation"; that the defendant was entitled to witness fee and legal fees. This was after dismissing other sums claimed as damages on the basis that the amounts did "not constitute the actual loss or damage by the defendant". As for the principle upon which legal costs were allowed, there were no specific discussions on the principle except at para [66] where the Court of Appeal referred to another earlier decision whereby this Court "highlighted that in fraudulent misrepresentation the assessment of damages is to put the innocent party in the position he would have been had he not relied on the fraudulent misrepresentation". This is a basic principle in compensation.

[53] We do not find these decisions to be authority for the proposition that costs may be claimed as special damages. Instead, we prefer the line of authorities as discussed above and which were in fact applied here - see Sunseekers Pte Ltd v. JSH Joshua [1990] 5 MLRH 442; Sitti Rajumah & Anor v. Mohd Rafiuddin Elmin [1996] 2 MLRH 890; Kembang Serantau Sdn Bhd v. YBK Usahasama Sdn Bhd [2020] 2 MLRA 679, to name a few.

[54] When Doyle v. Olby (Ironmongers) Ltd (supra) held that in the measure of damages where fraud has been successful proved, a defendant is bound to make reparation for all the actual damage directly flowing from the fraudulent act, it does not mean that costs and thereby the costs regime is subverted by the damages principles. The two concepts are quite different and must not be confused; the award of costs is entirely discretionary, whereas damages are an important element in a cause of action which must be proved. In Doyle v. Olby, the English Court of Appeal in fact proceeded to grant only actual damages proved; there were no claims neither was there any award for, legal fees and/or expenses incurred by the successful claimant.

Conclusion

[55] On principle and on policy including social policy, we agree with the line of authorities relied on by the appellants that the respondents are not entitled to claim as special damages, the legal charges, legal fees, legal costs or litigation costs in the same proceedings between the same parties.

[56] We answer the two questions posed in the appellants' favour. In line with the Commonwealth authorities cited and relied on by the appellants and discussed above, costs are indeed distinct from damages for the reasons adumbrated above. Costs including legal costs are not recoverable as special damages in the same proceedings between the same parties.

[57] The appeals are therefore allowed. We set aside the decisions of the Court of Appeal and the High Court on the award of legal fees as part of special damages. To be clear and for avoidance of doubt, the amount of RM2,604,000.00 is set aside. The other orders of the High Court are maintained.

[58] We further order costs of these appeals at the sum of RM50,000.00 subject to the payment of allocator fee.