Federal Court, Putrajaya

Mohamad Zabidin Mohd Diah CJM, Nallini Pathmanathan, Rhodzariah Bujang FCJJ

[Civil Appeal Nos: 01(f)-13-09-2021(W), 01(f)-12-09-2021(W), 01(f)-14-09- 2021(W) & 01(f)-55-09-2021(W)]

18 April 2023

Administrative Law: Exercise of administrative powers - Judicial review - Local authority - Planning permission - Discretion, exercise of - Whether grant of planning permission for proposed development located within a public park by local authority complied with statutory provisions of Federal Territory (Planning) Act of 1982

Land Law: Planning permission - Local authority - Discretion, exercise of - Judicial review - Whether grant of planning permission for proposed development located within a public park by local authority complied with statutory provisions of Federal Territory (Planning) Act of 1982

The present four appeals all related to the grant of planning permission by the Datuk Bandar of Kuala Lumpur ('Datuk Bandar'), as the relevant local authority, in respect of a proposed development which comprised a part of, and was located within, a public park known as Taman Rimba Kiara. In dispute were the merits of a judicial review application, where neighbouring properties and persons ('Respondents') sought to quash the grant of permission for the proposed development by the local authority, primarily on the basis that it did not conform to or comply with the statutory provisions of the Federal Territory (Planning) Act of 1982 ('FT Act'). Although the Respondents sought relief solely against the local authority, three other parties were successfully joined as parties in the initial application for judicial review before the High Court. They comprised: (i) the landowner of the subject land on which the proposed development was to be constructed - Yayasan Wilayah Persekutuan ('Yayasan'); (ii) the developer - Memang Perkasa Sdn Bhd ('Memang Perkasa'); and (iii) an association of longhouse residents who resided on the subject land.

At first instance, the High Court refused to quash the grant of planning permission and dismissed the application for judicial review. The Court of Appeal reversed the High Court's decision and granted, inter alia, an order quashing the decision of the Datuk Bandar. The aggrieved parties, who comprised the Appellants, sought and obtained leave to appeal in respect of the following eight questions of law.

(1) Whether O 53 r 2(4) of the Rules of Court 2012 ('ROC') was confined to the determination of threshold locus standi or whether it extended to confer substantive locus standi upon an applicant in an application for judicial review having regard to the decisions of the Court of Appeal in QSR Brands Bhd v. Suruhanjaya Sekuriti and of the Federal Court in Tan Sri Haji Othman Saat v. Mohamed bin Ismail and in Malaysian Trade Union Congress v. Menteri Tenaga, Air dan Komunikasi ('Leave Question No. 1'); (2) whether an applicant seeking judicial review of a development order was required to come within the terms of r 5(3) of the Planning (Development) Rules 1970 ('Planning Rules 1970') before he or she might be granted relief having regard to the decision in District Council Province Wellesley v. Yegappan ('Leave Question No. 2'); (3) whether the requirement of locus standi in judicial review proceedings set out in O 53 r 2(4) of the ROC might override the provisions of r 5(3) of the Planning Rules 1970, the latter being written law, having regard to the decision of the Federal Court in Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai v. Muziadi bin Mukhtar ('Leave Question No. 3'); (4) in law, whether a management corporation (1st to 4th Respondents) or joint management body (5th Respondent) established pursuant to s 39 of the Strata Titles Act 1985 ('STA') and s 17 of the Strata Management Act 2013 ('SMA') had: (i) the necessary power to initiate a judicial review proceeding to challenge a planning permission granted on a neighbouring land; (ii) the locus standi to initiate a judicial review proceeding on matters which did not concern the common property of the management corporation or joint management body; and (iii) the power to institute a representative action on behalf of all the proprietors on matters which were not relevant to the common property ('Leave Question No. 4'). (5) Whether the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan ('KL Structure Plan') was a legally binding document which a planning authority must comply with when issuing a development order having regard to the decisions of the Federal Court in Majlis Perbandaran Pulau Pinang v. Syarikat Bekerjasama Serbaguna Sungai Gelugor Dengan Tanggungan and the Court of Appeal in Perbadanan Pengurusan Sunrise Garden Kondominium vs Sunway City (Penang) and connected appeals ('Leave Question No. 5'); (6) whether, in the absence of a statutory direction to the contrary, a planning authority in deciding to issue a development order was under a duty at common law to give any or any adequate reasons for its decision to persons objecting to the grant of the development order having regard to the decisions in Public Service Board of New South Wales v. Osmond, of the Federal Court in Pihak Berkuasa Negeri Sabah v. Sugumar Balakrishnan and that of the Court of Appeal in The State Minerals Management Authority, Sarawak & Ors v. Gegah Optima Resources Sdn Bhd ('Leave Question No. 6'); (7) if the answer to Leave Question No. 6 was in the affirmative, then whether the reasons must be conveyed to the objectors at the time of its communication or whether reasons might be given in an affidavit opposing judicial review proceedings ('Leave Question No. 7'); and (8) where the High Court in judicial review proceedings negatived actual bias or a conflict of interest on the part of an authority issuing a development order, whether the Court of Appeal was entitled to hold that there nevertheless would be a likelihood of bias having regard to the conflicting decisions in Steeples v. Derbyshire Country Council, R v. Sevenoaks District Council, ex parte Terry and R v. St Edmundsbury Borough Council ex parte Investors in Industry Commercial Properties Ltd ('Leave Question No. 8'). These questions of law arose from the primary all-encompassing issue of whether the Datuk Bandar had exercised his discretion correctly and lawfully, namely, within the ambit of the specific powers afforded to him as an entity under the FT Act, in granting planning permission for the construction of the proposed development ('Impugned Development Order').

Held (dismissing the four appeals by the Appellants against the 6th to 10th respondents with costs; allowing the appeals against the 1st to 5th respondents with no order as to costs):

(1) In the present set of appeals, the use of the Comprehensive Development Plan ('CDP') - gazetted plans dating back to 1967 - was wrongly relied on by the Datuk Bandar some 35 years after the introduction of the structure plan system (from the date of coming into force of the FT Act versus the date when the Impugned Development Order was granted). And such use was relied on some 10 years after the KL Structure Plan was completed and the draft local plan in existence. Given further the proviso to s 22 in sub-s (5), where the Datuk Bandar might stay his hand on the grant of planning permission until the structural plans were ready, it begged the question why reliance was still placed on the CDP. This was particularly so when the CDP was wholly inapplicable in relation to the subject land, which fell outside of it. In these circumstances, particularly given the paucity of facts and circumstances explaining how and why the Datuk Bandar exercised its discretion, it was difficult to accept that the Datuk Bandar exercised its discretion in accordance with or within the ambit of s 22 of the FT Act. The exercise of the discretion by the Datuk Bandar under s 22 was fundamentally flawed as it contravened s 22(4) of the FT Act. As s 22(4) had not been correctly complied with, the Datuk Bandar's ability to depart from the statutory development plan, ie the KL Structure Plan, as envisaged under s 22(1) was similarly tainted. This meant that s 22 of the FT Act had been contravened. This in itself rendered the exercise of discretion by the Datuk Bandar invalid and rendered such exercise an illegality. (paras 206-209)

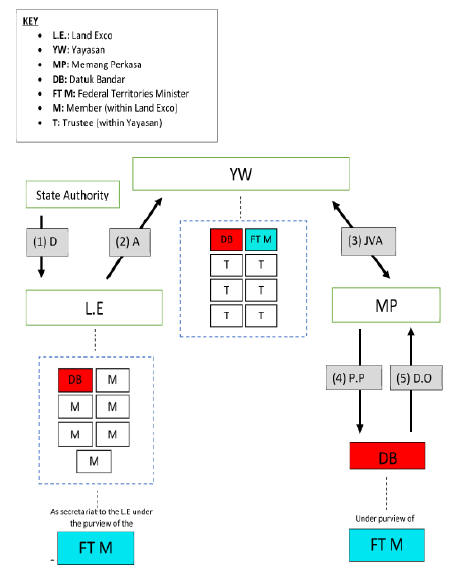

(2) The fact that the Datuk Bandar sat on the Land Exco which took the decision to alienate the land to Yayasan was relevant and significant, as this was a matter of public record, which ought to have been disclosed to the Court from the very outset. It was not for the Court to have to make an independent ascertainment of this fact. It fell within the purview of the duty of disclosure of the Datuk Bandar. Moreover, it was a pertinent fact because when it was considered in conjunction with the other salient facts, namely that the Datuk Bandar also sat on the Board of Trustees of Yayasan and was the entity that determined whether or not planning permission was to be granted in respect of any development on the subject land, it became a relevant fact for the purposes of ascertaining conflict of interest and/or bias. It meant that the Datuk Bandar effectively wore three 'hats' in three different capacities all of which had a significant effect on the issues of whether a conflict of interest and/or bias situation subsisted or not. The factual matrix disclosed that the Datuk Bandar was a part of the entity that approved the subject land's alienation, a part of the Applicant for planning permission, ie Yayasan that had delegated its powers to Memang Perkasa by way of a power of attorney, as well as the entity that granted the Impugned Development Order. Therefore, applying the test in Steeples (supra), namely that in the eyes of a reasonable person who was not present at the meeting and did not know the actual fairness of the decision reached, the facts here taken collectively warranted the conclusion that there was a real likelihood that the provisions in the JVA which required, inter alia, Yayasan to use its best endeavours to obtain planning permission, did have a material and significant effect on the Datuk Bandar as an institution, to grant the planning permission. This meant that the exercise of discretion was not independent, fair or in accordance with the law. (paras 244, 245, 250 & 313)

(3) Each of the Respondents had standing to sue by reason of their complaint of an encroachment into their private rights as well as their rights as a member of the public. Each of them claimed a loss of a private right to enjoy their rights of access to part of what was a public park. This was a private right. They were also in their capacity as members of the public who had a right to contribute towards the development of their area via the KL Structure Plan and in that context enjoyed a public law right. Both appeared to have been affected, for purposes of standing to sue, in the present appeals. However, the 1st to 5th Respondents, as management corporations and a joint management body, were statutory corporations. There was nothing in the relevant legislation that expressly allowed the 1st to 5th Respondents to file these judicial review applications in their own right and in a representative capacity for the owners and residents of the property to quash the development order made by the Datuk Bandar in respect of the subject land. Further, the power to initiate judicial review proceedings could not be implied into s 21(1)(i) of the STA. As such, by reason of the fact that the 1st to 5th Respondents lacked capacity to bring these proceedings as they could not represent each individual parcel proprietor or lessee in their individual condominiums, they lacked the requisite standing to bring these proceedings. (paras 479, 484, 488 & 493)

(4) The decision of the Datuk Bandar in the instant case was to grant planning permission on land that formed part of a green open space known as Taman Rimba Kiara. Taman Rimba Kiara had a history of being viewed and utilised as a public park. The planning permission granted also contravened provisions of the KL Structure Plan as well as the Draft KL Local Plan as was presented to the public and subjected to objection hearings. It would therefore require very strong reasons for the local authority to contravene the KL Structure Plan and it followed that affected persons, such as the Respondents here, had a right to be told why the local authority considered the Impugned Development Order as justified, notwithstanding its adverse effect on Taman Rimba Kiara. The public interest element that was implicit in the FT Act requiring that the relevant decision maker had considered matters properly was put into sharp focus in a case such as this where the grant of planning permission was a departure from the KL Structure Plan. That in itself warranted the giving of reasons for such departure. The reasons were to be given at the time when a decision was communicated to the objectors, rather than when a challenge had been brought and the Datuk Bandar explained its actions. This was to enable the objectors to comprehend why a decision had been taken in a particular way. The reasons given should be sufficient to enable the objectors to make an informed decision as to whether or not the decision in relation to planning permission was to be challenged. (paras 528, 529 & 534)

(5) Disclosure was of significance in matters such as the present, relating to planning approvals and the process of granting the same, as these matters had consequences on larger issues with vested public interest, ie, the township of Kuala Lumpur, the governance of the Datuk Bandar as a public authority, and environmental protection in general. Full disclosure was of primary importance in the exercise of the Court's supervisory jurisdiction in judicial review, because it was disclosure that enabled the Court to examine and assess whether a contravention of statute had occurred. Possible contraventions of law, in turn, comprised the precise subject matter of judicial review, as it was for a superior Court to determine whether a statutory body had acted ultra vires its parent Act. Where a Court ascertained that there were issues relevant to the matter at hand which had not been brought to the attention of the Court by the parties through their counsel, the Court was not thereby precluded from making judgments on such issues, provided the Judge highlighted this to the parties in dispute and gave them an opportunity to submit before the Court on these points. As this issue of fact and law was relevant to the case before the Court, and as this fact was not disclosed by the Datuk Bandar, all parties were accorded an opportunity to further submit on this point, in accordance with the rules of natural justice. However, it should be stressed that in compliance with the duty of disclosure it was incumbent upon the Datuk Bandar and any other party that was aware of this fact, and the law relating to it, to provide disclosure. (paras 551-554)

(6) In respect of Leave Question No. 1, O 53 r 2(4) of the ROC related to threshold locus standi. The reference to substantive locus standi was effectively a reference to the substantive merits of the case, which allowed the Court to review its finding on threshold locus standi in view of the factual and legal matrix of the entirety of the matter. A person or entity might well fall within the broad approach to 'adversely affected' as envisaged under O 53 r 2(4) in the context of the particular area of law or statute dealing with the subject matter of a case, but yet might not succeed on a substantive examination of the matter because when the entirety of the legal and factual matrix was analysed, he might not have met the requirements to warrant the grant of the various remedies available under judicial review. The term 'adversely affected' was to be analysed in the context of the legal and factual matrix within which the application was made, not in vacuo. (para 562(a))

(7) Leave Question No. 2 would be answered in the negative for the following reasons: (i) r 5(3) of the Planning Rules 1970 did not come into play as the subject land did not fall within the CDP; (ii) r 5(3) was wholly inconsistent with the statutory development plan, namely, the Structure Plan and therefore was inapplicable by virtue of s 65 of the FT Act; (iii) reliance on s 22(4) of the FT Act to justify the use of r 5(3) was erroneous in light of the inapplicability of the CDP to the subject land; (iv) more importantly, the discretion granted to the Datuk Bandar to diverge from the statutory development plan did not equate to reliance on r 5(3); and (v) the Datuk Bandar moreover failed to establish whether and how he gave due consideration to the Structure Plan before choosing to rely on the CDP which, in any event, was inapplicable in relation to the subject land. (para 562(b))

(8) Leave Question No. 3 was misconceived and there was no question of O 53 'overriding' r 5(3). Order 53 r 2(4) enabled a person who was adversely affected or had a genuine interest in a matter to initiate judicial proceedings. The judicial proceedings necessarily related to a particular area of the law. This meant that in the present case, when a Court was assessing whether or not a person was 'adversely affected' within the meaning of O 53 r 2(4), the Court did so in the context of the FT Act, not in vacuo. (para 562(c))

(9) All three parts of Leave Question No. 4 would be answered in the negative because the capacity to sue could not be implied into the STA and the SMA. As for Leave Question No. 5, the Structure Plan was a legally binding document which a planning authority must comply with, insofar as the statutory provisions of s 22 provided. Older pieces of legislation which did not sit harmoniously with the FT Act ought not to be relied upon or utilised as the prevailing or governing law in determining planning or development post the Structure Plan. Leave Question No. 6 would be answered in the affirmative on the facts of this case and in light of the provisions of the FT Act. As for Leave Question No. 7, such reasons were to be given at the time when a decision was made and was communicated to the objectors, rather than in an affidavit filed when a Court challenge had been brought. (para 562(d)-(g))

(10) In relation to Leave Question No. 8, this Court declined the tests found in Edmundsbury (supra) and Sevenoaks (supra) and preferred the principles enunciated in Steeples (supra) and to that end upheld the decision of the Court of Appeal which correctly applied the case. There was a conflict of interest and/or bias afflicting the decision of the Datuk Bandar, which was a separate and independent ground of challenge. It therefore followed that on this ground alone the Impugned Development Order was void and ought to be set aside. (para 562(h))

(11) It was incumbent upon the Court to protect public interest when land allocated for open space by the Datuk Bandar and approved by the Minister of the Federal Territories, was removed from public use and utilised for private ownership, to the detriment of public use. That too, without the knowledge of the public. This was particularly so when the net effect of such use by the issuance of the Impugned Development Order, contravened several sections as well as the purpose and object of the FT Act. Fundamentally, the Impugned Development Order contravened the KL Structure Plan as it changed the use of the area in question from open space for public use to mixed development. The exercise of discretion by the Datuk Bandar was not in conformity with his duties and obligations as spelt out in s 22(4) as well as ss 10 and 11 of the FT Act. The Impugned Development Order was therefore null and void and was correctly quashed by the Court of Appeal. The decision of the Court of Appeal was affirmed, save for the issue of title to sue in relation to the 1st to 5th respondents. (paras 569-571)

Case(s) referred to:

Amber Court Management Corporation & Ors v. Hong Gan Gui & Anor [2016] 2 MLRA 25 (refd)

Boyce v. Paddington Borough Council [1903] 1 Ch 109 (refd)

Badan Pengurusan Tiara Duta v. Timeout Resources Sdn Bhd [2014] 5 MLRA 500 (refd)

Bank Pertanian Malaysia Berhad v. Koperasi Permodalan Melayu Negeri Johor [2015] 6 MLRA 297 (refd)

Council of Civil Service Unions v. Minister for the Civil Service [1985] AC 374 (refd)

Datuk Haji Harun Haji Idris v. Public Prosecutor [1977] 1 MLRH 438 (refd)

Durayappah v. Fernando [1967] 2 AC 337 (refd)

District Council Province Wellesley v. Yegappan [1966] 1 MLRA 582 (distd)

Ermakov [1996] 2 All ER 302 (refd)

Giannarelli and Others v. Wrath and Others (1988) 81 ALR 417 (refd)

Gouriet v. Union of Post Office Workers and Others [1977] 3 All ER 70 (refd)

Government of Malaysia v. Lim Kit Siang & Another Case [1988] 1 MLRA 178 (overd)

Great Portland Estates plc v. Westminster City Council [1984] 3 All ER 744 (refd)

Gurit Kaur Sohan Singh v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur [2018] MLRHU 1659

Metropolitan Properties Co (FGC) Ltd v. Lannon [1969] 1 QB 557 (refd)

Kesatuan Pekerja-pekerja Bukan Eksekutif Maybank Berhad V. Kesatuan Kebangsaan Pekerja-pekerja Bank & Anor [2017] 4 MLRA 298

Lim Cho Hock v. Government of the State of Perak and Others [1980] 1 MLRH 418 (refd)

Malaysia Shipyard and Engineering Sdn Bhd v. Bank Kerjasama Rakyat Malaysia Bhd [1985] 1 MLRA 114 (refd)

Malaysian Trade Union Congress v. Menteri Tenaga, Air dan Komunikasi & Anor [2014] 2 MLRA 1 (refd)

Minister of Labour, Malaysia v. Lie Seng Fatt [1990] 2 MLRA 219 (refd)

Mohamad Hassan Zakaria v. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia [2017] 6 MLRA 470

Mohamed Ezam Mohd Nor & Ors v. Ketua Polis Negara [2001] 1 MLRA 630 (refd)

Oakley v. South Cambridgeshire DC [2017] EWCA Civ 71 (folld)

Penang Development Corporation v. Teoh Eng Huat & Anor [1993] 1 MLRA 161 (refd)

Pengarah Tanah dan Galian Wilayah Persekutuan v. Sri Lempah Enterprises Sdn Bhd [1978] 1 MLRA 132 (refd)

Perbadanan Pengurusan Sunrise Garden Kondominium v. Sunway City (Penang) Sdn Bhd & Ors And Another Appeal [2023] 3 MLRA 44 (refd)

Perbadanan Pengurusan Sunrise Garden Kondominium v. Sunway City (Penang) [2021] MLRAU 139 (refd)

Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai v. Muziadi bin Mukhtar [2019] 6 MLRA 307 (distd)

Pihak Berkuasa Negeri Sabah v. Sugumar Balakrishnan [2002] 1 MLRA 511 (refd)

Public Prosecutor v. Tengku Adnan Tengku Mansor [2020] 4 MLRA 730 (refd)

Prestaharta Sdn Bhd v. Badan Pengurusan Bersama Riviera Bay Condominium And Another Appeal [2017 MLRAU 557 (refd)

Public Service Board of New South Wales v. Osmond (1986) 159 CLR 656 (refd)

QSR Brands Bhd v. Suruhanjaya Sekuriti [2006] 1 MLRA 516 (refd)

R (on the application of Bancoult) v. Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2018] EWHC 1508 (refd)

R (on the application of Bancoult (No 2)) v. Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2016] UKSC 35 (refd)

R (on the application of CPRE Kent) v. Dover District Council and Another [2017] UKSC 79; [2018] 2 All ER 121 (refd)

R (on the application of Quark Fishing Ltd) v. Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2002] All ER (D) 450 (refd)

R v. Edmundsbury Borough Council, ex parte Investors in Industry Commercial Properties Ltd [1985] 3 All ER 234 (distd)

R v. Inland Revenue Commissioners, Ex parte National Federation of Self-Employed & Small Businesses Ltd [1982] AC 617 (refd)

R v. Lancashire CC, ex p Huddleston [1986] 2 All ER 941 (refd)

R v. Secretary of State for Environment, ex p Rose Theatre Co (1990) 1 All ER 754 (refd)

R v. Secretary of State for Social Services, ex parte Child Poverty Action Group (1989) 1 All ER 1047 (refd)

R v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex p Doody [1994] 1 AC 531 (refd)

R v. Sevenoaks District Council, ex parte Terry [1985] 3 All ER 226 (distd)

Ramachandran Appalanaidu & Ors v. Dato Bandar Kuala Lumpur & Anor [2012] 6 MLRA 62 (distd)

Rahman bin Abdullah Munir & 67 Lagi v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur & Anor [2008] 2 MLRA 390

Regina v. Gough [1993] AC 646 (folld)

Rohana Ariffin & Anor v. Universiti Sains Malaysia [1989] 4 MLRH 718 (refd)

Save Britain's Heritage v. Secretary of State for the Environment and Others [1991] 2 All ER 10

Simpson v. Edinburgh Corporation [1960] SC 313 (refd)

Steeples v. Derbyshire County Council [1984] 3 All ER 468 (folld)

Stefan v. General Medical Council [1999] 1 WLR 1293 (refd)

South Wales v. Osmond (1986) 159 CLR 656 (refd)

Tan Sri Haji Othman Saat v. Mohamed Ismail [1982] 1 MLRA 496 (refd)

The State Minerals Management Authority, Sarawak & Ors v. Gegah Optima Resources Sdn Bhd [2020] MLRAU 119 (refd)

Tengku Abdullah ibni Sultan Abu Bakar v. Mohd Latiff Shah Mohd & Ors and Other Appeals [1996] 2 MLRA 563 (refd)

Tweed v. Parades Commission [2006] UKHL 53 (refd)

Walton v. Scottish Ministers 2012 UKSC 44; [2013] PTSR 51 (refd)

YAM Tunku Dato' Seri Nadzaruddin Ibni Tuanku Ja'afar v. Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur & Anor [2002] 3 MLRH 313 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Building and Common Property (Maintenance and Management) Act 2007, s 8(2)

City of Kuala Lumpur (Planning) Act 1973, s 48(1)

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, ss 17, 25(2)

Emergency (Essential Powers) Ordinance No 46, 1970,s 47

Federal Capital Act 1960, s 5

Federal Constitution, art 74

Federal Territory (Planning) Act 1982, ss 1, 2(b), 7(1)(2)(ii), (3)(4)(5)(6), 8, 9(1), 10(1), 11, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19(1), 22(1), (4)(a), 23, 24(2), 30, 64(1), 65(1), (2)(a)

Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967, s 17A

Local Government Act 1976, ss 16(4), 17(1)

National Land Code, s 12

Planning (Development) Rules 1970, r 5(3)

Rules of Court 2012, O 15 r 12(1), O 53 r 2(4)

Strata Management Act 2013, ss 8(2)(g), 17, 21(1)(2), 59(1)(2)

Strata Titles Act 1985, ss 21(1), 39

Town and Country Planning Act 1968 [UK], s 9

Town and Country Planning Act 1971, [UK], s 9

Town and Country Planning Act 1990, [UK], s 15

Other(s) referred to:

Halsbury's Laws of England, 4th edn, vol 9, p 779

MP Jain's Administrative Law of Malaysia and Singapore, 4th edn, p 306

Malaysian Town and Country Planning - Law and Procedure, p 10

SM Thio's Locus Standi and Judicial Review, p 232

Counsel:

For the appellant: B Thangaraj (M Nalani with him); M/s Thangaraj & Associates

For the 1st-4th, 6th, 8th, 10th-13th respondents: Gurdial Singh Nijar (Christopher Leong, Abraham Au, Alliff Benjamin Suhaimi, Phoebe Loi Yean Wei, Joyce Pang with him); M/s Thomas Philip

For the 5th respondent: Cecil Abraham (Satharuban Sivasubramaniam, Sunil Abraham, Muzalifah Shabudin, Ranjini Anndy with him); M/s Satha & Co

For the 7th respondent: Gopal Sri Ram (Khoo Guan Huat, Austen Pereira, Joshua Teng with him); M/s Skrine

For the 9th respondent: Jayanthi Balaguru (Sathiya Dewi with her); M/s Jayanthi Balaguru

For the watching brief: Pretam Singh Darshan Singh (K Rajasegaran, Kalvinder Singh Bath with him); M/s Pretam Singh, Nor & Co

For the watching brief: Shireen Selvaratnam (Gokul Radhakrishnan with him); M/s Sreenavasan

JUDGMENT

Nallini Pathmanathan FCJ:

I. Introduction

[1] Four appeals are brought before this Court, all relating to the grant of planning permission by the Datuk Bandar of Kuala Lumpur, as the relevant local authority, in respect of a proposed development which comprises a part of, and is located within, a public park known as Taman Rimba Kiara.

[2] In dispute are the merits of a judicial review application, where neighbouring properties and persons ('the respondents') sought to quash the grant of permission for the proposed development by the local authority, primarily on the basis that it did not conform to or comply with the statutory provisions of the Federal Territory (Planning) Act 1982 ('FT Act').

[3] Although the respondents sought relief solely against the local authority, three other parties who could, potentially, be affected by any decision of the Court in this regard, applied to intervene in the proceedings. They were successfully joined as parties in the initial application for judicial review before the High Court.

[4] They comprise:

(i) The landowner of HSD 119599 PT 9244, Mukim Kuala Lumpur, Tempat Bukit Kiara, Daerah Kuala Lumpur ('the subject land') on which the proposed development is to be constructed - Yayasan Wilayah Persekutuan;

(ii) The developer - Memang Perkasa Sdn Bhd; and

(iii) An association of longhouse residents - Pertubuhan Penduduk Perumahan Awam Bukit Kiara, who presently reside on the subject land.

[5] At first instance, the High Court refused to quash the grant of planning permission and dismissed the application for judicial review. The Court of Appeal reversed the decision of the High Court and on 27 January 2021 granted, inter alia, an order quashing the decision of the local authority, namely the Datuk Bandar Kuala Lumpur.

[6] The aggrieved parties, who comprise the appellants, sought and obtained leave to appeal in respect of eight questions of law (which are set out further on in the judgment).

II. The Parties

A. The Appellants

[7] The appellants in this Court comprise:

(a) The Datuk Bandar of Kuala Lumpur ('Datuk Bandar') in Civil Appeal No: 01(f)-13-09-2021(W) ('No 13');

(b) Yayasan Wilayah Persekutuan ('Yayasan') in Civil Appeal No: 01(f)-12-09-2021 ('No 12');

(c) Memang Perkasa Sdn Bhd ('Memang Perkasa') in Appeal No 01(f)-14-09-2021(W) ('No 14'); and

(d) Pertubuhan Penduduk Perumahan Awam Bukit Kiara, Dewan Bandaraya Taman Tun Dr Ismail Kuala Lumpur ('the Long House Association') in Civil Appeal No: 02(f)-55-09-2021 ('No 55').

B. The Respondents

[8] The respondents comprise residents and property owners in Taman Tun Dr Ismail, Kuala Lumpur ('TTDI'). They are essentially persons or entities, who live within a 150 to 350 metre radius of the proposed development and maintain that they are adversely affected by it. More specifically:

(1) The 1st to 5th respondents are the Management Corporations and Joint Management Body representing the proprietors of condominiums or apartments neighbouring the proposed development;

(2) The 6th respondent is the public officer of the registered residents' association for TTDI;

(3) The 7th to 10th respondents are long-time residents and frequent users of Taman Rimba Kiara.

III. These Appeals

[9] The appellants' grievances in this series of four appeals are manifold. The commonality in their complaints include the following:

A. Locus Standi

(1) The Court of Appeal finding that the respondents enjoy the requisite locus standi to initiate the judicial review proceedings in the High Court, when they are in point of fact not 'qualified objectors' under r 5(3) of the Planning (Development) Rules 1970 [PU(A) 7/1971] (the Planning Rules 1970). In this context they complain that the Court of Appeal erred in concluding that in judicial review proceedings, r 5(3) is not relevant. They further challenge the conclusion of the Court of Appeal that the Respondents are not mere busybodies but have a real and genuine interest in the proposed development, in that it will adversely affect their lives and properties, and they therefore enjoy locus standi;

(2) The Court of Appeal construing O 53 r 2(4) of the Rules of Court 2012 ('RC 2012') as conferring both threshold and substantive locus standi;

(3) The failure of the Court of Appeal to consider that r 5(3) of the Planning Rules 1970 'cannot be overridden' by O 53 r 2(4) which is subsidiary legislation.

In short, these complaints centre on the scope and ambit of locus standi under Malaysian law. This requires a full examination, comprehension and consideration of 'locus standi' as borne out by written law and case law in this jurisdiction.

B. Duty to Consult and Hear

(4) That the Court of Appeal erred in imposing a common law duty on the Datuk Bandar to consult and hear objections from the respondents who do not fall within the purview of r 5(3) of the Planning Rules 1970 which restricts such right of consultation to a specific class of persons who do not include the 1st to 10th Respondents.

C. The Legal Status of the KL Structure Plan under the FT Act

(5) In finding that the KL Structure Plan 2020 is a legally binding document, the Court of Appeal erred. It is a policy document with no force of law;

D. Duty to Give Reasons

(6) The appellants complain that the Court of Appeal erred in deciding that the Datuk Bandar has a duty to give reasons for its decisions to objectors, notwithstanding the absence of a statutory provision requiring it to do so;

(7) They further maintain that the Court of Appeal erred in holding that the reasons for such decision must be conveyed to the objectors at the time the decision is communicated;

(8) It erred in finding that there is a common law duty to inform the objectors of the outcome of the hearing and the response to the objections raised; and

(9) The Court of Appeal also erred, as asserted, in deciding that the Datuk Bandar is precluded from supplementing its reasons for its decision in granting the Impugned Development Order ('the Impugned Development Order') by way of other facts and reasons subsequently deposed to by way of affidavit in judicial review proceedings.

E. Conflict of Interest

(10) The appellants claim that the Court of Appeal erred in applying the test for conflict of interest as set out in Steeples v. Derbyshire County Council [1984] 3 All ER 468 ('Steeples'), rather than that set out in R v. Edmundsbury Borough Council, ex parte Investors in Industry Commercial Properties Ltd [1985] 3 All ER 234 ('Edmundsbury');

(11) The Court of Appeal erred in concluding that there was a conflict of interest involving the Datuk Bandar, based on the Joint Venture Agreement between Yayasan and Memang Perkasa, given that the Datuk Bandar is a trustee sitting on the Board of Trustees of Yayasan and is also the head of the local authority. The latter is the sole authority empowered under the law to grant planning permission for the proposed development on the application of, and at the behest of the developer, Memang Perkasa.

IV. The Questions Of Law Upon Which Leave Was Granted For These Appeals

[10] The appellants have been granted leave to appear before the apex Court on the following eight questions of law:

(1) Whether O 53 r 2(4) of the Rules of Court is confined to the determination of threshold locus standi or whether it extends to confer substantive locus standi upon an applicant in an application for judicial review having regard to the decisions of the Court of Appeal in QSR Brands Bhd v. Suruhanjaya Sekuriti [2006] 1 MLRA 516 and of the Federal Court in Tan Sri Haji Othman Saat v. Mohamed bin Ismail [1982] 1 MLRA 496 and in Malaysian Trade Union Congress v. Menteri Tenaga, Air dan Komunikasi [2014] 2 MLRA 1?

('Leave Question No 1')

(2) Whether an applicant seeking judicial review of a development order is required to come within the terms of r 5(3) of the Planning Rules 1970 before he or she may be granted relief having regard to the decision in District Council Province Wellesley v. Yegappan [1966] 1 MLRA 582?

('Leave Question No 2')

(3) Whether the requirement of locus standi in judicial review proceedings set out in O 53 r 2(4) of the Rules of Court 2012 may override the provisions of r 5(3) of the Planning Rules 1970, the latter being written law, having regard to the decision of the Federal Court in Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai v. Muziadi bin Mukhtar [2019] 6 MLRA 307?

('Leave Question No 3')

(4) In law whether a management corporation (1st to 4th Respondent) or joint management body (5th Respondent) established pursuant to s 39 of the Strata Titles Act 1985 and s 17 of Strata Management Act 2013 has:

(i) the necessary power to initiate judicial review proceeding to challenge a planning permission granted on a neighbouring land?;

(ii) the locus standi to initiate a judicial review proceeding on matters which does not concern the common property of the management corporation or joint management body?; and

(iii) the power to institute a representative action on behalf of all the proprietors on matters which are not relevant to the common property?

('Leave Question No 4')

(5) Whether the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan is a legally binding documents which a planning authority must comply with when issuing a development order having regard to the decisions of the Federal Court in Majlis Perbandaran Pulau Pinang v. Syarikat Bekerjasama Serbaguna Sungai Gelugor Dengan Tanggungan [1999] 1 MLRA 336 and the Court of Appeal in Perbadanan Pengurusan Sunrise Garden Kondominium v. Sunway City (Penang) [2021] MLRAU 139 (Civil Appeal No: P-01(A)-222- 07-2017) and connected appeals?

('Leave Question No 5')

(6) Whether, in the absence of a statutory direction to the contrary, a planning authority in deciding to issue a development order is under a duty at common law to give any or any adequate reasons for its decision to persons objecting to the grant of the development order having regard to the decisions in Public Service Board of New South Wales v. Osmond (1986) 159 CLR 656, of the Federal Court in Pihak Berkuasa Negeri Sabah v. Sugumar Balakrishnan [2002] 1 MLRA 511 and that of the Court of Appeal in The State Minerals Management Authority, Sarawak & Ors v. Gegah Optima Resources Sdn Bhd [2020] MLRAU 119?

('Leave Question No 6')?

(7) If the answer to Leave Question No 6 above is in the affirmative, then whether the reasons must be conveyed to the objectors at the time of its communication or whether reasons may be given in an affidavit opposing judicial review proceedings?

('Leave Question No 7')

(8) Where the High Court in judicial review proceedings negatives actual bias or a conflict of interest on the part of an authority issuing a development order, is a Court of Appeal entitled to hold that there nevertheless would be a likelihood of bias having regard to the conflicting decisions in Steeples v. Derbyshire Country Council [1984] 3 ALL ER 468, R v. Sevenoaks District Council, ex parte Terry [1985] 3 All ER 226 and R v. St Edmundsbury Borough Council ex parte Investors in Industry Commercial Properties Ltd [1985] 3 All ER 234?

('Leave Question No 8')

V. The Primary All-Encompassing Issue For Consideration In These Appeals

[11] These questions of law however arise from the primary all-encompassing issue that requires adjudication in this administrative judicial review application. And that primary issue is whether the Datuk Bandar exercised its discretion correctly and lawfully, namely within the ambit of the specific powers afforded to it as an entity under the FT Act, in granting planning permission for the construction of the proposed development.

[12] Put another way, did the Datuk Bandar do, or omit to do anything such that the exercise of its discretion was ultra vires or unlawful? Judicial review is available only as a remedy for conduct of an authority which is ultra vires or unlawful, but not for acts done lawfully in the exercise of an administrative discretion, which are complained of only as being unfair or unwise.

[13] Judicial review is sought by the Respondents in relation to whether those circumscribed powers accorded to the Datuk Bandar under the FT Act were:

(a) Exercised legally, in conformity with, and within the ambit of the statute;

(b) Exercised rationally;

(c) Exercised with proportionality; and

(d) Exercised without bias and in accordance with the principles of natural justice.

[14] As these sub-issues, which together answer the primary issue of whether the Datuk Bandar exercised its discretion legally comprise mixed questions of fact and law, it is necessary to consider the relevant facts and law involved in these appeals. It is only after a consideration and analysis of the primary issue that the questions of law which require an answer can be answered appropriately. We, therefore, turn first to the relevant law, and then the facts, comprising the background to these appeals.

[15] That takes us to an examination of the relevant law, namely the FT Act. This is necessary because in order to analyse whether the Datuk Bandar exercised its powers and discretion legally and in conformity with the Act under s 22(4), it is necessary to comprehend the purpose and object of the FT Act.

[16] Put another way, the construction of s 22(4) FT Act requires a holistic construction of the FT Act rather than a consideration of the section in vacuo in order to arrive at its full meaning. This accords with s 17A of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967.

VI. The Purpose And Object Of The Federal Territory (Planning) Act 1982

[17] We shall first consider the purpose and object of the FT Act to construe how planning is controlled under the Act. This is necessary to understand how s 22 of the FT Act is to be interpreted when the section provides for reference to the provisions of the KL Structure Plan. Against this, we will then be in a position to determine whether the Datuk Bandar was acting within his statutory powers when he chose to grant the Impugned Development Order.

[18] The legislative history of the FT Act is a salient starting point.

A. The Legislative History Of The FT Act

[19] Prior to the FT Act, town planning and zoning had a long and somewhat complex legislative history in this jurisdiction.

[20] The legislative history of town planning in Malaysia is well set out in the comprehensive textbook on the subject entitled 'Malaysian Town and Country Planning - Law and Procedure'. As gleaned from this textbook as well as from the submissions of the parties, planning law in the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur commenced with the Sanitary Boards Enactment (Cap 137) which was enacted on 1 February 1930, later renamed the Town Boards Enactment (Cap 137). The former Act concentrated on health and sanitation including drainage as part of the law. [Nurul Syala Abdul Latip, Tim Heath, Shuhana Shamsuddin, M.S. Liew, Kalaikumar Vallyutham 'The Contextual Integration and Sustainable Development of Kuala Lumpur's City Centre Waterfront: And Evaluation of the Policies, law and Guideline' (ICSBI 2010) http://irep.iium.edu. my/310/1/UTP_conference.pdf]

[21] Pursuant to the Town Boards Enactment (Cap 137), in 1967, Plan No L886, L887, and L888 were gazetted under Gazette Notification No 1197 of 1967 and titled the Comprehensive Development Plan ('the CDP'). The CDP relied upon by the appellants are these gazetted plans dating back to 1967, and not the gazetted KL Structure Plan 2020 or the then draft KL Local Plan.

[22] On 20 August 1970, the Emergency (Essential Powers) Ordinance No 46 of 1970 [PU(A) 297/1970] (the Emergency Ordinance No 46') came into force, and the CDP was renamed Plan Nos 1039, 1040 and 1041 respectively (see s 4(1) of the Emergency Ordinance No 46) by the Minister for the Federal Capital of Kuala Lumpur. Per s 47 of the Emergency Ordinance No 46, the Planning (Development) Rules 1970 [PU(A) 7/1970] was enacted. These are the Planning Rules relied upon by the Datuk Bandar to-date.

[23] On 1 February 1972, Kuala Lumpur achieved city status as 'Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur' or 'the City of Kuala Lumpur' per the City of Kuala Lumpur Act 1971. On 1 February 1974, Kuala Lumpur became a Federal Territory per the Constitution (Amendment) (No 2 Act 1973 [Act A206].

[24] On 21 May 1973, the City of Kuala Lumpur (Planning) Act 1973 repealed the Emergency Ordinance No 46. Though the Emergency Ordinance No 46 was repealed, the CDP and the Planning Rules 1970 were allowed to remain in place per Part III of the City of Kuala Lumpur (Planning) Act 1973 insofar as they are not inconsistent with the provisions of the City of Kuala Lumpur (Planning) Act 1973.

[25] On 25 August 1982, the FT Act came into force, although in a piecemeal fashion. Parts I to III of the FT Act (being ss 1 to 18 of the FT Act) came into effect on that date. On 15 August 1984 (being the relevant date for Part X of the Federal Territory (Planning) Act), the Federal Territory (Planning) Act 1982 repealed the City of Kuala Lumpur (Planning) Act 1973.

[26] Pursuant to s 65(2)(a) of the FT Act, the Planning Rules 1970 and the CDP remained in force but only insofar as they are not inconsistent with the FT Act. The issue of whether the CDP and the Planning Rules 1970 are consistent with the FT Act or not, is a legal issue falling for consideration within these appeals.

[27] The Long Title to the FT Act sets out that it is an Act to make provisions for 'the control and regulation of planning in the Federal Territory' amongst others:

"An Act to make provisions for the control and regulating of proper planning in the Federal Territory, for the levying of development charges, and for purposes connected therewith or ancillary thereto."

[28] The FT Act was promulgated for the proper control and regulation of town and country planning in the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur. The Town and Country Planning Act 1976 applies to the rest of the country, but the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur has carved its own legislative path in view of it being the nation's capital. Article 74 of the Federal Constitution states that Parliament may make laws in the Federal List or Concurrent List in the Ninth Schedule. Item 27 of List I of the Ninth Schedule covers all matters relating to the Federal Territories and this allows Parliament to make laws for the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur.

[29] The FT Act achieves control and regulation primarily by employing a tiered series of development plans, as provided in Part III of the FT Act (or ss 7 to 18 of the FT Act). These development plans comprise a structure plan followed up by a local plan for the Federal Territory.

[30] A structure plan is defined in s 2 of the FT Act as a written statement accompanied by diagrams, illustrations and other descriptive matter containing policies and proposals in respect of the development and use of land. It is, in short, a master plan of planning policies for the entire region.

[31] A local plan is defined as a map and a written statement which formulates, in detail, proposals for the development and use of land in the area and contains matters specified by the Minister. The full definition is set out in s 2 read together with s 13 of the FT Act.

[32] Thus, the FT Act envisions development within the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur to take effect through this tiered series of development plans. Part III of the FT Act (or ss 7 to 18 of the FT Act) governs the content and manner of preparation, production, alteration, amendment, and the legal character of these development plans.

[33] The provisions of Part III of the FT Act cascade over to Part IV of the FT Act (or ss 19 to 30), which sets out how planning permission ought to be granted or prohibited in the region.

[34] As such, the FT Act envisages that the grant or prohibition of planning permission should accord with Part III, namely the development plans. In other words, the grant or refusal of planning permission hinges on adherence to these development plans. By way of metaphor, and to paraphrase Mohd Zawawi Salleh FCJ in Pihak Berkuasa Tatatertib Majlis Perbandaran Seberang Perai v. Muziadi bin Mukhtar [2019] 6 MLRA 307 ('Muziadi') 'the stream cannot rise above its source'.

[35] Here, the development plans in Part III are equivalent to the source, while the grant or prohibition in Part IV of the FT Act is the stream. This statutory cascade of Part III to Part IV ensures regulation and control are achieved in that the development plans comprise the base regulatory element and planning permission centres on compliance with those development plans, although the Datuk Bandar enjoys a discretion to depart from the same in certain circumstances.

[36] Therefore, in determining whether the grant or refusal of planning permission is in accordance with the FT Act or not, it is imperative that Part III and IV are read together, rather than in vacuo such that a harmonious construction is achieved. Conversely, if the planning permission provisions in Part IV are read in isolation, the result would not accord with the purpose of the Act which is to ensure regulation and control in accordance with the development plans in Part III. It would also result in planning permission being granted in a piecemeal fashion, running antithetically to a holistic construction of the Act. This would defeat the purpose of the Act, which requires compliance with the 'source'.

[37] We are additionally guided by the Hansard of the Dewan Rakyat dated 22 October 1981, as produced by the 1st to 10th Respondents, wherein the then Minister of Federal Territory during the second and third reading of the Federal Territory (Planning) Bill 1981, at pages 4288 - 4290 and 4320, stated that the CDP was intended to be replaced with the structure plan system which comprises a structure plan and a local plan:

(The English translation):

"Today, development in the Federal Territory is planned and controlled according to the provisions of the "Kuala Lumpur City (Planning) Act 1973 (Act 107) as amended by the Kuala Lumpur City (Planning) Act 1977 (Amendment) (Act A416/77). In Act 107, it is stated that development must be implemented based on the Comprehensive Development Plan, indeed this Comprehensive Development Plan not only has some specific weaknesses due to the emphasis on physical aspects, but it is also no longer in line with the rules of modern planning. Therefore this Comprehensive Development system needs to be replaced with a new system called the Structure Plan System as provided in the Bill presented...

This Structure Plan system has two important components which are: First the Structure Plan and Second the Local Plan..."

[38] From the Hansard of the Dewan Rakyat dated 22 October 1981, a few salient points may be distilled:

(i) The FT Act was proposed before Parliament to make better provisions for the control and regulation of proper planning in the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur; and

(ii) That the CDP system was to be replaced with a structure plan system comprising of a structure plan and a local plan as the comprehensive development system had weaknesses and was not in line with modern planning methods.

B. The Requirement For Public Participation In The Production Of The Development Plans

[39] A fundamental feature of the FT Act is the statutory requirement for public participation. As far back as the Town Planning Enactment of the Federated Malay States of Malaya, the need for public participation was recognised. It introduced, even then, the concept of public interest as justification for 'encroaching' on the development rights of landowners. [See Malaysian Town and Country Planning, Law and Procedure, (Malaysia: CLJ Publication, 2012) at page 10].

[40] It is no surprise that the element of public participation is also a fundamental feature of the FT Act in the land planning process. This element is therefore an integral part of the democratic process which enables the public to require accountability in relation to development in and around where they live.

C. Public Participation And The Development Plans

[41] This aspect, which requires public participation in the drawing up of both structural plans and local plans, is provided for in Part III of the FT Act (or ss 7 to 18 of the FT Act). The FT Act mandates a statutory process whereby draft development plans can only become complete by first going through a certain level of publicity at the very outset ('the Statutory Development Plans'). This is best demonstrated by the process by which a draft structure plan ('the Draft Structure Plan') becomes a gazetted structure plan ('the Gazetted Structure Plan').

[42] On the date of the FT Act coming into force or as soon as possible thereafter, the Datuk Bandar is required to submit the Draft Structure Plan to the Minister and a public notice relating to the Draft Structure Plan is to be published in the Gazette and in local newspapers ('the Public Notice'). The FT Act requires the Public Notice to contain, inter alia, particulars of the place where copies of the Draft Structure Plan may be inspected per s 7(1) and (2) of the FT Act. The statutory requirement that a draft development plan be open for public inspection and the invitation for written objections (and implicitly, the provision of an address where written objections may be submitted) demonstrates that the FT Act envisages and requires a considerable level of cooperation between the relevant local authority and the public in order to bring into effect the development plan.

[43] This issuance of a public notice per s 7(1) and (2) of the FT Act, above, is the minimum level of publicity the Draft Structure Plan must go through.

[44] Critically, the Draft Structure Plan is displayed and allows the public to object to its contents. The public are given the opportunity to shape the 'terms' of the Draft Structure Plan.

[45] This is evident from s 7(2)(ii) of the FT Act which provides that objections may be received 'from any person' as opposed to any specific category of persons. If there is no objection received, the Draft Structure Plan may only proceed to the next stage, ie, submission to the Minister, after the expiry of the period for objections per s 7(4). Nonetheless, if there is any objection received, a Committee appointed by the Minister pursuant to s 7(3) shall consider the objection as well as hear any person and report on such objection as stipulated in s 7(5) and (6). This whole scheme demonstrates that the right of objectors to be heard is safeguarded by the FT Act. In this regard, it may be said that the FT Act statutorily embeds the right of public discourse.

[46] Upon the Draft Structure Plan's approval by the Minister ('the Structure Plan'), the FT Act requires that another public notice in the Gazette and local newspapers is to be published, with details stating where copies of the Structure Plan may be inspected per s 9(1) of the FT Act. From the date of publication of the public notice in the Gazette, the Structure Plan shall come into effect.

[47] The effect of gazetting the public notice relating to the Structure Plan denotes/signifies that it is recognised in law as a statutory development plan which has to be complied with, as envisaged under the Act.

[48] At the outset of the Act's Long Title, the Act provides for 'the control and regulating of proper planning'. Whilst the Act does not specifically list out principles of proper planning, the Act labours to provide for the preparation and passing of statutory development plans that determines how the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur takes shape over the course of the next twenty years or so. Therefore, it may be said that the Act's purpose and object of providing for proper planning is encased within the statutory development plans.

D. Public Participation And Alteration, Addition, Revision, Or Replacement Of The Structure Plan

[49] At any time after the Structure Plan 'comes into effect', alteration is permitted so long as the proposed alteration undergoes the same level of publicity and the same procedure of an issued public notice and a hearing of objections as the Draft Structure Plan was subjected to (ie, subsections 7(2), (3), (4), (5), (6) and (7) and ss 8 and 9 shall apply per s 10(1) and 11 of the FT Act. In this respect, there is a consistent threshold of publicity accorded to the procedure for implementing any amendment or alteration to the development plan under the FT Act.

[50] Like the Town and Country Planning Act 1976, the FT Act also provides that all development plans pursuant to the Act garners legitimacy by passing through the public eye, and any changes thereafter to the same development plans must similarly traverse the same path in order to be accorded the same legitimacy.

E. Public Participation And The Local Plan

[51] In the same manner as the Structure Plan comes into being, draft local plans are crafted to provide detailed plans for each region within the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur. The draft local plan is expected to follow on closely from the Structure Plan.

[52] Draft local plans are accorded the same level of publicity as that given to the Structure Plan. Before they are adopted, the draft local plan must first be published by public notice in the Gazette and in local newspapers per s 14 ('the Draft Local Plan'). As is the case with the Draft Structure Plan, the Draft Local Plan may only proceed to the next stage of adoption by the Commissioner after the expiry of the period for objections or after the objections or representations have been considered per s 16(1), in keeping with the statutory leitmotif that objections are enshrined and accounted for. Having considered the mainstay of the FT Act, namely the conversion to, and implementation of a structure plan system as opposed to a comprehensive development system as previously practiced under earlier and repealed legislation, we now turn to the section detailing the powers conferred on the Datuk Bandar under the FT Act in relation to the grant or refusal of planning permission.

F. Section 22 Of The FT Act And The Datuk Bandar's Discretion

[53] The relevant section relating to the grant or refusal of planning permission for development is s 22 of the FT Act. It reads as follows:

"Development order

22. (1) The Commissioner shall have power exercisable at his discretion to grant planning permission or to refuse to grant planning permission in respect of any development irrespective of whether or not such development is in conformity with the development plan; provided however the exercise of the discretion by the Commissioner under this subsection shall be subject to subsection (4) and s 23.

(2) Where the Commissioner decides to grant planning permission in respect of a development he may issue a development order:

(a) Granting planning permission without any condition in respect of the development;

(b) Granting planning permission subject to such condition or conditions as the Commissioner may think fit in respect of the development:

Provided that the Commissioner shall not issue a development order under this subsection unless he is satisfied that the provision of s 41 relating to the assessment of development charges has been complied with.

(3) Without prejudice to the generality of para 2(b), the Commissioner may impose any or all of the following conditions.........

(4) The Commissioner in dealing with an application for planning permission shall take into consideration such matters as are in his discretion expedient or necessary for purposes of proper planning and in this connection but without prejudice to the discretion of the Commissioner to deal with such application, the Commissioner shall as far as practicable have regard to:

(a) the provisions of the development plan and where the local plan has not been adopted, the Comprehensive Development Plan; and

(b) any other material consideration:

Provided that, in the event of there being no local plan for an area and the Commissioner is satisfied that any application for planning permission should not be considered in the interest of proper planning until the local plans for the area have been prepared and adopted under this Act then the Commissioner may either reject or suspend the application.

(5) Upon receipt of an application for planning permission the Commissioner shall within such time as may be prescribed either grant or refuse the application and when the application is granted subject to condition or refused, the Commissioner shall give his reasons in writing for his decision."

[Emphasis Added]

[54] Section 22 prescribes in subsection (1) that the Datuk Bandar may grant planning permission irrespective of the development plan. The provision exempts the Datuk Bandar from following the statutory structure plan, but the exercise of that exemption is restrained or limited by the proviso to subsection (4) in the same section and s 23. This simply means that s 22(1) does not confer an absolute power of exemption on the Datuk Bandar to arbitrarily disregard or discount the provisions of the statutory development plan.

[55] Section 22(4) is multifaceted and contains several limbs. The first limb which reads "the Commissioner in dealing with an application for planning permission shall take into consideration such matters as are in his discretion expedient or necessary for purposes of proper planning makes it clear that the Datuk Bandar is required to take into consideration matters that are in his discretion expedient or necessary for proper planning.

[56] This means that the Datuk Bandar is obligated by law to consider matters which are expedient, ie beneficial or necessary for proper planning. We comprehend from the FT Act that proper planning refers to the system of planning and regulation underlying the Act, namely the structure plan system as opposed to the CDP system. So the need to consider the statutory development plans is an essential task, even if there is to be a subsequent departure from the same. What underscores the consideration of 'matters' for the exercise of the Datuk Bandar's discretion in this section, is the need to adhere to proper planning as envisaged under the Act.

[57] The Datuk Bandar's discretion as to what is expedient or necessary for purposes of proper planning appears to be worded widely. However, this does not detract from a statutory construction that such discretion should be exercised objectively and not subjectively or selectively. If the latter approach is adopted, this will necessarily lead to arbitrariness. Arbitrariness is precisely what a holistic reading of the Act seeks to prohibit. Therefore, in exercising its discretion, the Datuk Bandar is expected to act reasonably, logically and in conformity with the purpose and object of the Act. The same is propounded in the following judgments:

(1) Raja Azlan Shah FJ in Pengarah Tanah dan Galian Wilayah Persekutuan v. Sri Lempah Enterprises Sdn Bhd [1978] 1 MLRA 132:

"... Unfettered discretion is a contradiction in terms.. Every legal power must have legal limits, otherwise there is dictatorship. In particular, it is a stringent requirement that a discretion should be exercised for a proper purpose, and that it should not be exercised unreasonably. In other words, every discretion cannot be free from legal restraint; where it is wrongly exercised, it becomes the duty of the Courts to intervene. The Courts are the only defence of the liberty of the subject against departmental aggression. In these days when government departments and public authorities have such great powers and influence, this is a most important safeguard for the ordinary citizen: so that the Courts can see that these great powers and influence are exercised in accordance with law. I would once again emphasise what has often been said before, that "public bodies must be compelled to observe the law and it is essential that bureaucracy should be kept in its place", (per Danckwerts L.J. in Bradbury v. London Borough of Enfield [1967] 3 All ER 434 442.)"; and

(2) Hashim Yeop A Sani CJ (Malaya) in Minister of Labour, Malaysia v. Lie Seng Fatt [1990] 2 MLRA 219:

"The minister had a discretion under s 20(3) of the Act and that is not in dispute. The issue is whether the discretion is unfettered. To say it is an unfettered discretion is a contradiction in terms Unfettered discretion is another name for arbitrariness.

The minister's discretion under s 20(3) is wide but not unlimited. As stated earlier, so long as he exercises the discretion without improper motive, the exercise of discretion must not be interfered with by the Court unless he had mis-directed himself in law or had taken into account irrelevant matters or had not taken into consideration relevant matters or that his decision militates against the object of the statute. Otherwise he had a complete discretion to refuse to refer a complaint which is clearly frivolous or vexatious which in our view this is one."

[58] In order for a Court to assess whether the Datuk Bandar's discretion has in fact been exercised within the ambit of the Act, it is necessary that the Datuk Bandar explains or sets out the 'matters' that are in his objective opinion, expedient or necessary for purposes of proper planning, and which therefore caused him to exercise his discretion to either grant or refuse planning permission. Otherwise, it would not be possible for any party, the Court or the public to know or comprehend on what basis a decision was made to either allow or refuse planning permission. The issue of when such reasons ought to be given also arises for consideration in this series of appeals, and will be considered later.

[59] The construction above, to the effect that the discretion afforded in both subsection 1 and the first limb of subsection 4 is not an unfettered discretion is further borne out by the third limb of subsection 4. But first it is necessary to consider the effect of the connecting limb, the second limb.

[60] The second limb reads "...and in this connection but without prejudice to the discretion of the Commissioner to deal with such application...". This means that when considering those matters which the Datuk Bandar objectively reasons are expedient or necessary for the purposes of proper planning, but without detracting from his powers to exercise his discretion to either grant or refuse permission even where there is a departure from the statutory development plans.

[61] It is the limb that connects:

(a) the matters which the Datuk Bandar is obligated by law to consider and give effect to, in relation to proper planning; but

(b) seeks to preserve the Datuk Bandar's ability to depart from the development plans, in the exercise of his discretion as provided in subsection (1).

[62] Section 22 in its entirety seeks to reconcile the fundamental need for compliance with the statutory development plans, and the Datuk Bandar's power to depart from the same in subsection (1). This is achieved by granting such a discretion in subsection (1) but limiting and circumscribing the exercise of that power as specified in subsection (4).

[63] Put another way, subsection (1) of s 22 is circumscribed, defined and limited by subsection (4).

[64] Therefore, the words "without prejudice to the discretion of the Commissioner to deal with such application" serves the purpose of stipulating that although the Datuk Bandar is bound to adhere to the overarching purpose of proper planning, he may still depart from the development plan. Any such departure however is still subject to the third limb and the proviso to subsection (4).

[65] The third limb reads "the Commissioner shall as far as practicable have regard to - (a) the provisions of the development plan and where the local plan has not been adopted, the Comprehensive Development Plan; and (b) any other material consideration".

[66] The third limb pronounces that, subsections (a) and (b) "shall" be given regard to "as far as practicable". The use of the word 'shall', given the purpose and object of the FT Act, lends itself more favourably to the mandatory sense of the word. In other words, the Datuk Bandar is obligated in law, as far as is practicable to give regard to the provisions of the statutory development plan.

[67] It follows that it is only where the statutory local plan has not been adopted that the CDP is to be utilised instead. In construing subsection (a) it bears repeating that the same has to be read in a holistic context. The FT Act envisages that a structure plan is brought into force as soon as possible after the passing of the Act, followed shortly thereafter by the detailed local plan. It does not envisage a prolonged delay in the production and implementation of either the structure plan or the local plan. Any such delay, designed or otherwise, would serve only to undermine the purpose and object of the Act, namely regulated planning in accordance with public input and expectation as contained in the statutory development plans.

[68] As such, the legally coherent construction to be accorded to paragraph (a) of subsection 4 of s 22, more particularly in relation to the use of the CDP, is that recourse is to be had to the CDP in the early years following enactment and implementation of the FT Act, prior to the local plan being drawn up. The local plan in turn is expected to be drawn up and implemented within a short time of, if not before or at approximately the same time as the structure plan.

[69] Such an interpretation is further supported by the proviso to subsection 4 which allows for the Commissioner to reject or suspend the application for planning permission where he/it is satisfied that the proper planning requires that the local plans be drawn up and adopted under the Act. Proper planning again comes to the fore in the exercise of discretion by the Commissioner. Therefore, it follows that the CDP is not and cannot comprise an alternative to the local plan. The CDP is merely there to fill in a gap during the time when the local plan is being drawn up and gazetted. This proviso underscores the point that a long delay in the adoption of the local plan does not warrant automatic or prolonged utilisation of, or recourse to, the CDP.

[70] Put another way, the CDP is a saving provision to tide over the period pending the production and adoption of the local plan as the secondary tier of the Act's statutory development plan. As enumerated above, the statutory development plans are the Act's purpose and object. Therefore, where there is already the first tier of the statutory development plan in place, ie, the structure plan, the CDP may be referred to in a manner that does not oust and conflict against the statutory development plans in order to give true effect to the Act.

[71] Subsection (b) of s 22(4) reads that "any other material consideration" is to be regarded in addition to subsection (a). The use of the word 'and' envisages that both limbs ought to be adhered to and one cannot be cherry-picked at the expense of ignoring the other.

[72] What factors or matters then comprise "any other material consideration" in the context of subsection (b)? Given the Act's purpose and object, the test of what constitutes "any other material consideration" when deciding whether or not to grant planning permission, is whether the "consideration" serves a planning purpose within the four corners of the Act.

[73] In Great Portland Estates plc v. Westminster City Council [1984] 3 All ER 744 where the English Town and Country Planning Act 1971 was in operation, it was held that development plans 'are concerned with the use of land and more particularly with its 'development', a term of art in planning legislation' and thus a material consideration is a consideration that 'serves a planning purpose... And a planning purpose is one which relates to the character of the use of land'.

[74] We are of the view that this definition or test aptly describes the character of a material consideration. The definition incorporates the primary requirement of serving a planning purpose, which is an essential element of the FT Act. Additionally, planning purpose is then defined as a purpose which relates to the character of the use of the land. Applying this test, that which amounts to a material consideration should relate to the use of land and how a change in its use may affect the wider development of the region.

[75] Within s 22(4) alone, there have been two references to the phrase "proper planning". The Long Title of the FT Act also enshrines the phrase "proper planning". While the Act does not explicitly set out a definition of 'proper planning' it is evident that the Act labours to provide for the statutory development plans as the instrument to implement development within the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur. As such, statutory development plans comprise the basis for proper planning.

[76] Having considered the purpose and object of the FT Act including in particular s 22(4) FT Act which provides the background law to be applied in the present appeals, we move on to consider the salient background facts of the instant case.

VII. Salient Background Facts And Law

A. The History Of Taman Rimba Kiara

[77] The chronology of events giving rise to this dispute dates back to the 1970's. As stated by the 1st to 10th Respondents, Taman Rimba Kiara in its entirety was a public park measuring 25.2 acres located within the TTDI and Bukit Kiara area. Earlier, it was part of a privately owned rubber estate which was subsequently acquired by the State Authority in the 1970's.

[78] The 1st to 10th Respondents submit, premised on a master plan produced by an architect at the time, that the aim was to turn the entire area into the KL Botanical Gardens, with a National Arboretum and Heroes' Mausoleum. It was designated to be a large-scale nursery to serve and support the larger botanical gardens and national arboretum. This did not materialize.

[79] The Datuk Bandar in submissions containing plans has acknowledged that the subject land is designated and coloured as a 'green area' in the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2020 ('KL Structure Plan).

[80] As a consequence of the acquisition of the entire 25-acre area by the Government, the former workers of the rubber estate and their families, were re-housed in longhouses in the north eastern corner of Taman Rimba Kiara. These residents were promised long-term, permanent housing by the Government. That did not transpire. The proposed development is expected to resolve this almost 50-year-old promise by the Government, vide the construction of the 29-storey block to house all the residents of the longhouses. There are presently some 100 families in this longhouse community.

B. The Subject Land And The Proposed Development

[81] The land on which the proposed development is supposed to be built is identified as HSD 119599, PT 9244, Mukim Kuala Lumpur, Tempat Bukit Kiara, Daerah Kuala Lumpur. It measures 12 acres ('the Subject Land'). The proposed development itself comprises 9 blocks of high-rise apartments, more particularly 8 blocks of 42-54-storey serviced apartments and 1 block of 29-storey affordable apartments, with basement and podium carparks ('the Proposed Development').

C. The KL Structure Plan 2020

[82] On 16 August 2004, in compliance with the Federal Territory (Planning) Act 1982, the public notice containing the approval of the Draft Structure Plan was gazetted. The effect of the KL Structure Plan was to set out in general terms how land in various parts of the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur would be utilised. This naturally affected the 25 acres comprising Taman Rimba Kiara.

[83] The KL Structure Plan 2020, which was produced in 2004, zones the area comprising Taman Rimba Kiara, including the Subject Land, as a green open space. As such the Structure Plan envisaged the area as comprising public space for public use. It is significant that the KL Structure Plan also stipulates that it is the intention of the Datuk Bandar that the KL Structure Plan is to be followed and supported by the KL Local Plan:

"Adalah menjadi hasrat Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (DBKL) supaya pelan struktur di ikuti dan di sokong oleh pelan tempatan atau pelan-pelan tempatan. [Paragraph 12 of the Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2020]"

[84] In May 2008, again in compliance with the FT Act, the draft KL Local Plan was presented to the public after going through the specific procedures prescribed under the FT Act. The entire 25 acres of Taman Rimba Kiara was zoned as a public park and a green open space. In this context, cl 8.3 of the draft KL Local plan specifies the area as 'Cadangan Taman Awam dan Kawasan Lapang'.

[85] Objection hearings with the public, as envisaged under the FT Act took place from September 2008 to May 2009 with respect to the draft KL Local Plan. The KL Local Plan was intended to be completed by September 2011, but due to a series of delays was only finally gazetted on 30 October 2018.

D. Alienation Of The Subject Land

[86] In the interim, Yayasan applied to the State Authority of Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur for the alienation of the Subject Land, ie, the 12 acres of land on which the proposed development is to be built. This meant alienating 12 acres from the original land, identified as Lot 55118, comprising 25.5 acres known as Taman Rimba Kiara.

[87] On 8 November 2012 and 14 December 2012, a Land Executive Committee of the Federal Territory ('Land Exco') meeting was held to consider an appeal by Yayasan for the alienation of 12 acres of Taman Rimba Kiara.

[88] In the course of the hearing of these appeals, this Court asked, whether the Datuk Bandar had sat as one of the members of the Land Executive Committee as required by law under s 12 of the National Land Code as modified in the Federal Territory (Modification of National Land Code) (Amendment) Order 2004 [PU(A) 220/2004]). The question posed by the Court was then answered in the affirmative by counsel for the Datuk Bandar. This fact had not previously been disclosed by the Datuk Bandar to the Courts below. It is therefore unclear whether the Datuk Bandar alerted other Land Exco members that the KL Structure Plan specified the Subject Land/ Taman Rimba Kiara as a green open space.

[89] It is unclear whether statutory rectification and amendment of the KL Structure Plan (per ss 10 and 11 of the FT Act) was carried out pursuant to the Subject Land/Taman Rimba Kiara's change of land use, ie, whether there was a hearing of objections before the public concerning a change of land use spreading across 25.2 acres. Any lay person reading the KL Structure Plan would most likely conclude that the Subject Land/Taman Rimba Kiara was still, and would remain, a green open space.