High Court Malaya, Shah Alam

Tee Geok Hock JC

[Civil Suit No: BA-22NCVC-178-04-2021]

21 October 2022

Contract: Tenancy agreement - Lands rented out to plaintiff by local authority ("defendant") - Agreements terminated on ground lands required for public purpose - Claim for damages and refund of rentals paid - Whether public purpose not a valid and sufficient ground for premature termination of tenancy in absence of express provision for early termination in tenancy agreement - Whether termination wrongful, null and void - Whether defendant misrepresented itself as being registered owner of lands - Whether defendant as local authority could sign contract to rent out part of open space within its local authority area and collect rentals - Whether plaintiff estopped from questioning defendant's title to possession of lands - Whether defendant unjustly enriched at expense of plaintiff - Whether award of exemplary or punitive damages warranted

The plaintiff had entered into two tenancy agreements with Majlis Bandaraya Shah Alam ("defendant"), the first of which was dated 8 February 2012 (" 1st Tenancy Agreement") and the second ("2nd Tenancy Agreement"), 9 June, 2017 for the tenancy of two adjacent plots of land ("lands") the titles to which were registered in the name of the Selangor State Government. The 1st Tenancy Agreement and in particular, clause 4(h) thereof provided for the early termination by the defendant of the said agreement before the date of expiry thereof, by giving an advance written notice of 30 days to the plaintiff without the need to specify any reason, and that the defendant should not be liable for any loss, damage or difficulties suffered by the plaintiff from such early termination. There was no such provision in the 2nd Tenancy Agreement for early termination by the defendant before the expiry thereof except in the event of default by the plaintiff. The defendant subsequently by way of Notices of Termination dated 26 April 2018 and 27 April 2018 respectively terminated the 1st and 2nd Agreements on the basis that the lands were required for a public project. The plaintiff commenced proceedings against the defendant and sought inter alia a declaration that the termination of the aforesaid agreements was wrongful, the refund of the monies paid as rentals under undue influence, as well as punitive and exemplary damages. The plaintiff contended that the defendant had misrepresented itself as being the registered proprietor of the said lands, and the defendant as a local authority, had no authority to earn rentals from the said lands and therefore the collection of the rentals by the defendant was illegal. The plaintiff also contended that there was unjust enrichment to the defendant at its expense. The defendant denied any misrepresentation on its part and argued that the termination of the said tenancy agreements was valid as the lands were required for a public project; that the termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement was justified and had been acquiesced to by the plaintiff when it evacuated the lands; and that the plaintiff was not entitled to any refund of the rentals or damages.

Held (termination of 1st Tenancy Agreement was valid and not wrongful; termination of 2nd Tenancy Agreement was wrongful; defendant to pay the plaintiff RM48,000 as special damages and RM20,000 as one third of the costs of actions; order accordingly):

(1) The Notice of Termination dated 26 April 2018 which gave more than 30 days' notice in writing to the plaintiff, complied with the termination procedure stipulated in clause 4(h) of the 1st Tenancy Agreement . In the circumstances, the termination was valid and not wrongful. (paras 42 & 44)

(2) The Notice of Termination dated 27 April 2018 which purported to give notice of early termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement , was issued in breach of the contract and was wrongful as there was no express provision in the 2nd Tenancy Agreement for early termination of the said agreement by the defendant. (para 49)

(3) Public purpose was a legal justification for the compulsory acquisition of lands by a public authority but it would not be a valid and sufficient ground for the premature termination of a tenancy by a landlord in absence of an express contract clause for such early termination upon the occurrence of such an event. Where the tenancy of the land had to be prematurely terminated due to the land being compulsorily acquired under the Land Acquisition Act 1960 or being required for a public purpose, damages for the premature termination would have to be paid by the landlord to the tenant. In the circumstances, and given the fact that the plaintiff was not and would not be compensated by the public authority that took over the land, it had therefore not lost its right to claim damages against the defendant for the premature termination of the tenancy. (paras 51-53)

(4) The plaintiff had acted lawfully and reasonably in evacuating the lands and in not opposing the intended construction works as the lands were urgently required for a public purpose. Hence the plaintiff could not be unjustly held to have acquiesced to a wrongful termination of the second tenancy agreement. (para 54)

(5) Based on the maxim jus tertii, in a suit for eviction or trespass, a tenant would be barred from questioning the title of the landlord in the absence of an adverse claim for title by a third party. Analogous to the effect of the said maxim, a tenant would be estopped by s 116 of the Evidence Act 1950 from denying or questioning the landlord's title to possession. There clearly was in this case, a landlord-tenant relationship between the parties, and the plaintiff had enjoyed peaceful and undisturbed occupation and possession of the lands until the date of termination of the tenancies. The substance of the tenancy was fulfilled and enjoyed by both parties. In the circumstances, the plaintiff was estopped from denying the defendant was the landlord and had the lawful title/right to rent out the lands and to collect the rentals; and the allegation of misrepresentation against the defendant was irrelevant and of no legal consequence. (paras 57-60, 62-63)

(6) On the evidence, the rights in respect of the said lands were allocated/ given by the State Authority to the defendant. In light of the provisions of the Local Government Act 1976 and the natural and ordinary meaning of the word "rents", there could not be any legal objection to a local authority signing a tenancy contract to rent out part of an open space within its local authority area, and collecting the rentals. In the context of the present case, the defendant's renting out of the lands to the plaintiff flowed directly from or was incidental to its administration of the relevant part of the local authority and was not a purely commercial transaction as such. (paras 70, 72-73)

(7) On the facts, there had been no material misrepresentation by the defendant that it was the registered proprietor of the lands. In the context of a sale and purchase agreement, representation as to "registered proprietor" and "beneficial owner" would be a material representation, as only the registered proprietor and/or the beneficial owner would have the lawful authority to sell the land; whereas in a tenancy agreement, representation as to lawful authority to rent out the land would be a material consideration as persons other than the registered proprietor and beneficial owner could have the lawful authority to rent out the land. Hence, whether or not the landlord was the registered or beneficial owner, was immaterial, so long as the landlord had the lawful authority to rent out the land. (paras 75-76 & 80)

(8) A party who was not the registered proprietor of land could be the lawful landlord of the said land. In the premises, the defendant as the local authority was entitled to rent out temporarily any public area or open space within its local authority area that belonged to the State Government. The alleged misrepresentation by the defendant as to its status as the registered proprietor or beneficial owner, even if it was made, did not affect the defendant's capacity as landlord to lawfully rent out the lands. In the circumstances, the plaintiff was not entitled to a refund of the rentals paid by it. (paras 81-85)

(9) Given the plaintiff's failure to plead the elements or material facts for a cause of action for unjust enrichment, and the fact that it had enjoyed peaceful possession of the lands and had benefited from the use thereof, it was not unjust for the defendant to keep the rentals collected from the plaintiff. (paras 87-89)

(10) The termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement was for a bona fide reason and for a public purpose. There were no aggravating circumstances, oppressive acts, or conduct on the part of the defendant in doing so. The plaintiff therefore, was only entitled to claim for losses and damages caused by the wrongful termination of the said agreement. There was no valid or sufficient basis for exemplary or punitive damages to be awarded against the defendant. (paras 96-97)

Case(s) referred to:

Ban Kok Hotel v. Low Phek Choon [1950] 1 MLRA 576 (refd)

Guan Soon Tin Mining Co v. Ampang Estate Ltd [1972] 1 MLRA 125 (refd)

Guinness Anchor Marketing Sdn Bhd v. Man Seng Trading & Marketing Sdn Bhd [2021] MLRAU 237 (refd)

Rethnasamy v. Teoh Ngoo Mooi & Anor [1982] 1 MLRH 753 (refd)

Simcity-Ete Venture Sdn Bhd v. Koperasi Pembangunan Kampung Tradisional Tasek Pulau Pinang Berhad [2022] 2 MLRA 472 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Contracts Act 1950, ss 74, 116

Evidence Act 1950, s 116

Local Government Act 1976, ss 3, 8, 13, 19, 36, 39, 56

Town and Country Planning Act 1974, s 43

Counsel:

For the plaintiff Subramaniam Paramasivam; M/s Adliza Subra Siti & Partners

For the defendant: Azmer Saad; M/s Lainah Yaacob & Zulkepli

JUDGMENT

(After Full Trial)

Tee Geok Hock JC:

Introduction

[1] The disputes in the present case relate to the plaintiff-tenant's claims for reliefs and damages arising from the defendant- landlord's termination of two separate tenancy agreements for two adjacent plots of vacant land.

[2] When the two adjacent plots of vacant land were required for purposes of LRT 3 public transportation project on Park N Ride, the defendant-landlord terminated the tenancy agreements. The plaintiff-tenant takes the position that the termination of tenancies was wrongful, and sues for declaratory reliefs and damages.

[3] After a full trial of 3 days, this Court held that one tenancy agreement was wrongly terminated while the other tenancy agreement was validly terminated. This Court awarded some damages to the plaintiff in respect of the tenancy agreement which was wrongfully terminated.

[4] Both the plaintiff-tenant and the defendant-landlord are unhappy with the decision and they have both filed their respective Notices of Appeal.

Parties' Pleaded Case And Defences

[5] The plaintiff in the present case seeks a declaration that the Tenancy Agreements for the two plots of land (if valid) were wrongfully terminated by the defendant and praying for damages of RM696,697.00; a declaration that both the Tenancy Agreements were null and void and prays for refund of RM576,220.00 as rentals paid under undue influence; and prayer for punitive and exemplary damages and for costs. Among others, the plaintiff alleged that the defendant misrepresented to the plaintiff that the defendant was the registered proprietor of the said lands.

[6] On the other hand, the defendant's position is that there was no misrepresentation, that the tenancy agreements were validly terminated as they were required for a public project, and that the plaintiff was not entitled to any refund of rental or any damages.

Cause Papers And Full trial

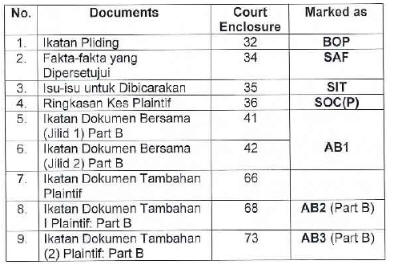

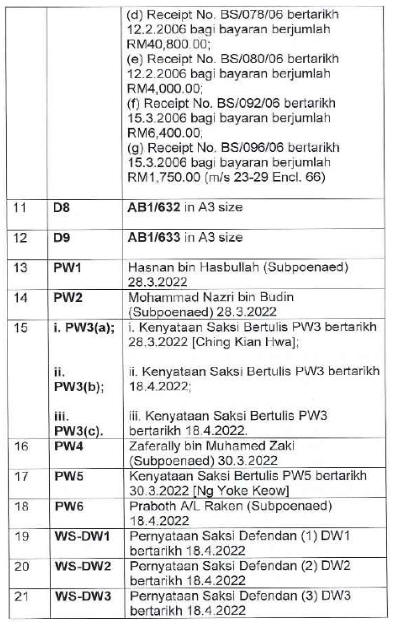

[7] At a pre-trial case management session, the following documents in the cause papers were marked with the respective numbers as stated below:

[8] It was also the agreed procedure that:

(1) At the full trial, upon the witness' affirmation and confirmation of the contents of his/her Witness Statement as his/her evidence, the Witness Statement and its contents are deemed to be read and there is no necessity for the witness to read the contents of the Witness Statement into the CRT system. This procedure is without prejudice to the rule against hearsay, ie the principle of evidence which requires witnesses to testify as to facts and matters within their personal knowledge and not on hearsay evidence. Liberty is given to the Counsel to ask supplementary or additional questions in examination-in-chief to clarify or explain or highlight salient parts of the Witness Statement before the cross-examination begins.

(2) In order to save time and costs at the full trial, the Part A and Part B documents referred to in the witnesses' statements and evidence are marked as per the marking of Agreed Bundles of Documents as "AA" and "AB" numbers respectively followed by the page numbers and there is no necessity to mark the relevant pages of the Part A and Part B documents with separate exhibit numbers again. However, this procedure shall be without prejudice to the rule against hearsay. Part C document, when either upgraded into Part B document or its original has been tendered by the maker and verified as authentic, shall be marked with a separate exhibit number.

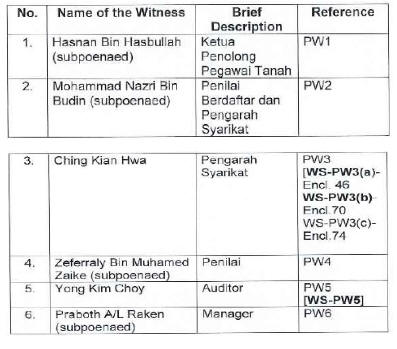

[9] The trial proceeded for 3 days on 28 March 2022, 30 March 2022 and 18 April 2022 at which the following 9 witnesses attended and gave oral evidence:

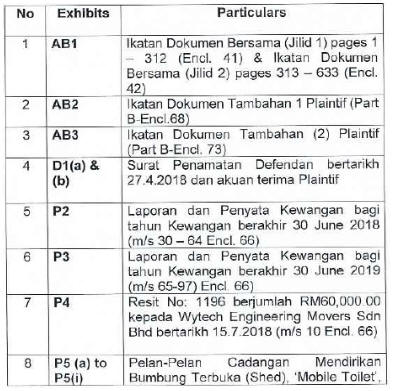

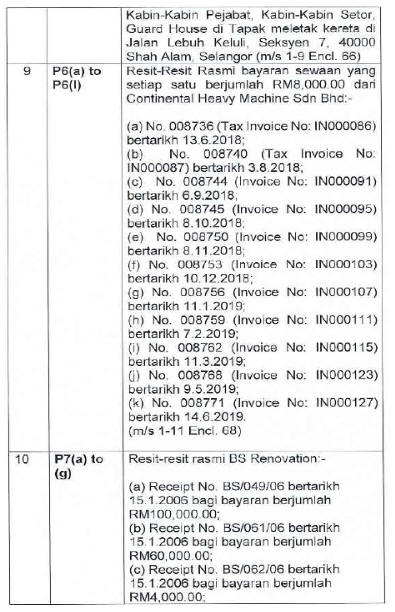

[10] The following exhibits were marked before and/or during the trial:

Agreed Facts

[11] Through the Statement of Agreed Facts marked as "SAF" (encl 34), the parties agreed to the following facts:

i. Plaintif adalah sebuah syarikat yang ditubuhkan di bawah Akta Syarikat 1965 dan mempunyai alamat berdaftar di B607, 6th Floor, Block B, Kelana Square, 17 Jalan SS7/26, Kelana Jaya, 47301 Petaling Jaya, Selangor dan alamat perniagaan di No 28 & 30, Lebuh Keluli, Kawasan Perindustrian Bukit Raja Selatan, 40000 Shah Alam Selangor Darul Ehsan.

ii. Defendan adalah sebuah badan statutori (pihak berkuasa tempatan) yang ditubuhkan menurut Akta Kerajaan Tempatan 1976 Akta 171 dan mempunyai alamat di Wisma MBSA, Persiaran Perbandaran, 40000 Shah Alam Selangor.

iii. Defendan telah mengeluarkan surat tawaran bertarikh 15 September 2005 kepada plaintif untuk penyewaan tapak gerai di Jalan Lebuh Keluli Seksyen 7, Shah Alam, Selangor.

iv. Defendan dan plaintif telah menandatangani Perjanjian Penyewaan Tapak pada 18 June 2008 (Perjanjian Penyewaan Tapak Pertama) untuk tempoh satu tahun dari 1 April 28 hingga 31 Mac 2009.

v. Defendan telah melanjutkan tempoh Perjanjian Penyewaan Tapak Pertama kepada plaintif dengan menandatangani beberapa perjanjian lanjutan tempoh penyewaan bertarikh 5 Januari 2010, 20 Mei 2010 dan 8 Februari 2012.

vi. Perjanjian Penyewaan Tapak Pertama telah dilanjutkan dari 1 April 2012 hingga 31 Disember 2016.

vii. Pada 8 Februari 2016 defendan telah mengeluarkan tawaran lanjut tempoh penyewaan tapak pertama kepada plaintif bagi tempoh 3 tahun lagi daripada 1 Januari 2017 hingga 31 Disember 2019 dengan menandatangani satu perjanjian Penyewaan Tapak Majlis bertarikh 9 Jun 2017.

viii. Plaintif telah menandatangani Perjanjian Penyewaan Tapak Gerai dengan defendan bertarikh 24 Disember 2008 (Perjanjian Tapak Tambahan).

ix. plaintif telah menandatangani beberapa perjanjian lanjutan untuk penyewaan tapak tambahan dengan defendan bertarikh 15 April 2010 dan 24 Januari 2011 untuk tapak tambahan.

x. Pada 26 April 2018 defendan telah memberi notis penamatan perjanjian sewa tapak untuk menyerahkan milikan kosong pada 1 Jun 2018 kepada plaintif.

[12] During the trial, the parties agreed that during the many years of the tenancies, the plaintiff has paid a total cumulative amount of RM576,220.00 as rentals to the defendant.

Issues To Be Tried

[13] By the Statement of Issues to be Tried in encl 35 (marked as "SIT") the parties agreed to the following issues to be tried:

(i) whether the Termination Notice dated 26 April 2018 was valid under the laws;

(ii) whether the Termination Notice dated 26 April 2018 could terminate 2 different Tenancy Agreements;

(iii) whether the defendant made representation to the plaintiff that the defendant was the registered proprietor of the said lands;

(iv) whether the plaintiff is entitled to the damages pleaded In the Statement of Claim, ie (a) the total amounts of rentals paid to the defendant; and (b) costs of restoration of the said lands.

[14] As there are two parcels of vacant lands involved here, for ease and convenience of reference this Court will refer to the two parcels of land as "the 1st Land" for "Tapak" or "Tapak Letak Kenderaan di Jalan Lebuh Keluli, Seksyen 7, 40000 Shah Alam; "the 2nd Land" for "Tapak Gerai di Jalan Lebuh Keluli, Seksyen 7, 40000 Shah Alam; the Tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land as "the 1st Tenancy Agreement" and the Tenancy Agreement for the 2nd Land as "the 2nd Tenancy Agreement". The A0 size approved plan of the Bukit Raja Prime Industrial Park wherein the 1st Land and the 2nd Land are located was tendered as Exhibit "D9" at the full trial.

Evaluation And Findings

The 1st Tenancy Agreement For The 1st Land

[15] By a Tenancy Agreement dated 8 February 2012 ("the 1st Tenancy Agreement") the defendant as the landlord let and the plaintiff as the tenant took on rental the land described as 'Tapak" or "Tapak Letak Kenderaan di Jalan Lebuh Keluli, Seksyen 7, 40000 Shah Alam ("the 1st Land"); AB1/55 -75 (encl 41). This tenancy was extended by letter dated 8 December 2016 for 3 years from 1 January 2017 until 31 December 2019 on the same terms as the 1st Tenancy Agreement but with amendments to some commercial terms: see AB1/76 - 77 (encl 41). See WS-PW3 Ching Kian Hwa Q&A 19 to 25 (encl 46); SAF paragraphs iii to vii.

[16] The 1st Tenancy Agreement is a continuation of a number of previous tenancy agreements between the same parties in relation to the 2nd Land which dates back to 18 June 2003: see AB1/6 - 127 (encl 41). See WS-PW3 Ching Kian Hwa Q&A 19 to 25 (encl 46); SAF paragraphs iii to vii.

[17] The 1st Land of 21,780 sq ft is located at part of the Bukit Raja Prime Industrial Park [see exhs D8 in A3 size and D9 in A0 size]. It is rented out to the plaintiff at a rental of RM4,000 per month under the extension letter, equivalent to RM0.19 per sq ft per month: see item 2(a)(ii) of the extension letter for the 1st Tenancy Agreement [AB1/76 (encl 41)]. See WS-PW3 Ching Kian Hwa Q&A 24 (encl 46).

[18] The tenure of the tenancy of the 1st Land is 3 years from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019; see item 2(a)(ii) of the extension letter for the 1st Tenancy Agreement [AB1/76 (encl 41)]. The specific purpose permitted for use of the 1st Land by the tenant is for parking of cars: see item 12 of the Schedule to the 1st Tenancy Agreement [AB1/73 (encl 41)].

[19] The tenant has no option for renewal or extension of the tenancy of the 2nd Land: see item 9 of the Schedule to the 1st Tenancy Agreement [see AB1/73 (encl 41)]. Any application for extension of tenancy of the 2nd Land has to be made in writing by the tenant and is subject to the discretion of the landlord and subject to terms to be mutually agreed upon: clause 1(f) of the 1st Tenancy Agreement [see AB1/58 (encl 41)].

[20] Clause 4(a) of the 1st Tenancy Agreement provides that the landlord is entitled to terminate the tenancy in the event of default by the tenant or upon the insolvency or winding-up of the tenant: see AB1/65 (encl 41). Clause 4(g) of the 1st Tenancy Agreement provides that the tenant may terminate the tenancy of the 1st Land by giving to the landlord 90 days of advance notice: see AB1/68 (encl 41).

[21] Clause 4(h) of the 1st Tenancy Agreement provides that the landlord may make an early termination of the tenancy before its date of expiry by giving an advance written notice of 30 days to the tenant without the necessity to state any reason, and in such event the landlord shall not be responsible for any loss, damages or difficulty which the tenant may suffer as a result of such early termination: see AB1/68 (encl 41).

The 2nd Tenancy Agreement For The 2nd Land

[22] By a Tenancy Agreement dated 9 June 2017 ("the 2nd Tenancy Agreement") the defendant as the landlord let and the plaintiff as the tenant took on rental the additional land described as "Tapak Gerai di Jalan Lebuh Keluli, Seksyen 7, 40000 Shah Alam ("the 2nd Land"): AB1/128 - 161 (encl 41). See WS-PW3 Ching Kian Hwa Q&A 26 to 30 (encl 46).

[23] The 2nd Tenancy Agreement is a continuation of a number of previous tenancy agreements between the same parties in relation to the 2nd Land which dates back to 18 June 2008: see AB1/6 - 127 (encl 41). See WS-PW3 Ching Kian Hwa Q&A 26 to 30 (encl 46). SAF paragraphs viii and ix (encl 34).

[24] The 2nd Land of 21,780 sq ft is located at part of the Bukit Raja Prime Industrial Park: see exhs D8 in A3 size and D9 in A0 size. It is rented out to the plaintiff at a rental of RM4,000 per month, equivalent to RM0.19 per sq ft per month: see item 6 of the Schedule to the 2nd Tenancy Agreement [AB1/149 (encl 41)].

[25] The tenure of the tenancy of the 2nd Land is 3 years from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019: see item 5 of the Schedule to the 2nd Tenancy Agreement [see AB1/149 (encl 41)]. The specific purpose permitted for use of the 2nd Land by the tenant is for parking of motor vehicles: see item 12 of the Schedule to the 2nd Tenancy Agreement [ AB1/150 (encl 41)].

[26] The tenant has no option for renewal or extension of the tenancy of the 2nd Land: see item 9 of the Schedule to the 2nd Tenancy Agreement [see AB1/149 (encl 41)]. Any application for extension of tenancy of the 2nd Land has to be made in writing by the tenant and is subject to the discretion of the landlord and subject to terms to be mutually agreed upon: clause 2.2 of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement [see AB1/131 - 132 (encl 41)].

[27] Clause 7.1(a) of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement provides that the landlord is entitled to terminate the tenancy in the event of default by the tenant: see AB1/140 - 141 (encl 41). Clause 7.1(b) of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement provides for immediate termination of the tenancy upon the insolvency or winding-up of the tenant: AB1/141. Clause 7.1 (c) of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement provides that the tenant may terminate the tenancy of the 2nd Land by giving to the landlord 90 days of advance notice: see AB1/141 (encl 41). Under the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land, this is no clause for the landlord to terminate the tenancy before its expiry by giving written notice except in the event of the tenant's default.

Notices Of Termination

[28] By Notice of Termination dated 26 April 2018 issued by the defendant-landlord to the plaintiff-tenant, the defendant notified the plaintiff of the termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 1st Land (Tapak Tempat Letak Kenderaan) with effect from 31 May 2018 and asked the plaintiff to vacate the 1st Land by 31 May 2018 [AB1/463 (encl 42)]. In the said Notice of Termination, the defendant stated that the reason for termination was that the 1st Land was required for STN16 (Bukit Raja Station) of the Park N Ride project. See WS-PW3 Ching Kian Hwa Q&A 38 (encl 46).

[29] By Notice of Termination dated 27 April 2018 issued by the defendant-landlord to the plaintiff-tenant, the defendant notified the plaintiff of the termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land (Tapak Gerai) with effect from 31 May 2018 and asked the plaintiff to vacate the 2nd Land by 31 May 2018 [Exhibit "D1(a)" and, D1(b)" in encl 40; see cross-examination of PW3 Ching Kian Hwa on 28 March 2022 wherein PW3 Ching admitted that this Notice of Termination dated 27 April 2018 in respect of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement was received by the plaintiff]. In the said Notice of Termination, the defendant stated that the reason for termination was that the 2nd Land was required for STN16 (Bukit Raja Station) of the Park N Ride project.

[30] In this connection, it is the finding of this Court and also the common position of the parties at the full trial that there were two (2) separate notices of termination, with one notice for each Tenancy Agreement, and therefore the Issue (ii) as framed in the Statement of Issues to be Tried is erroneous in that is seems to assume there was only one (1) single notice of termination for two (2) Tenancy Agreements.

Parties' Cases, Defences And Main Arguments Here

[31] The plaintiff's case here is that (a) the termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement and the 2nd Tenancy Agreement was wrongful and has caused losses and damages to the plaintiff; (b) the defendant has misrepresented in the Tenancy Agreements that the defendant was the "beneficial owner" or "registered proprietor" of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land.

[32] The defendant denies that the termination was wrongful and further denies that there was any misrepresentation. It was also the defendant's case that any buildings and/or structures built by the plaintiff on the 1st Land and the 2nd Land were illegal as they were built without written approval and/or permit by the defendant. The defendant denies the plaintiff's claims for alleged losses and damages.

[33] In paras 16, 16.1 and 18 of the Statement of Claim, the plaintiff pleaded that there was only one (1) notice of termination, ie Notice of Termination dated 26 April 2018, which did not specify which of the two Tenancy Agreements was terminated or whether both the Tenancy Agreements were terminated, and that such termination was pre-mature, defective and invalid under the laws.

[34] In this action, the defendant did not argue on the point of the ambit of pleadings.

[35] The Statement of Issues to be Tried dated 9 November 2021 stated the issues as follows:

(i) Sama ada Notis Penamatan defendan bertarikh 26 April 2018 sah di sisi undang-undang.

(ii) Sama ada Notis Penamatan defendan bertarikh 26 April 2018 boleh menamatkan 2 perjanjian sewaan yang berbeza.

(iii) Sama ada defendan membuat representasi bahawa defendan adalah pemilik Hartanah tersebut.

(iv) Sama ada plaintif berhak untuk ganti rugi sepertimana yang diplidkan dalam Pernyataan Tuntutan iaitu:

a) Jumlah sewa yang telah dibayar oleh plaintif atas perjanjian sewaan;

b) Kos pembaikpulihan Hartanah tersebut.

[36] In para 22 of the defendant's Written Submission, the defendant stated the issues to be tried are as follows:

(a) Whether the Termination Notice dated 26 April 2018 and 27 April 2018 are valid.

(b) Whether the defendant had represented to the plaintiff that the defendant was the registered proprietor of the (two) 2 lots located at Jalan Lebuh Keluli Seksyen 7, 40000 Shah Alam, Selangor.

(c) Whether the renewal of the tenancy agreement can be construed that the permit for construction is automatically approved.

(d) Whether the plaintiff is entitled to claim for damages.

[37] In the plaintiff's Written Submission when dealing with the specific issues, the plaintiff put the 1st and 2nd issues as "whether the Notices of Termination dated 26 April 2018 and 27 April 2018 are legal and valid under the settled laws", the 3rd issue as "Whether the defendant represented that it was the registered owner of both said Tapak Gerai and Tapak", and the 4th issue as "Is the plaintiff entitled for the damages as pleaded in the said SOC dated 23 April 2021"

Issue 1: Whether The Termination Of The 1st Tenancy Agreement (Tapak Letak Kenderaan) Is Wrongful?

[38] Clause 4(h) in the Tenancy Agreements dated 5 January 2010 [AB1/27 (encl 41)], 20 May 2010 [AB1/48 (encl 41)], 8 February 2012 [AB1/68], dibaca Bersama-sama dengan Surat Lanjutan bertarikh 8 December 2016 [AB1/76 (encl 41)] in respect of the 1st Land (Tapak Letak Kenderaan) reads as follows:

"(h) Tanpa menjejaskan Klausa 4(a), Tuan Tanah boleh menamatkan Perjanjian ini lebih awal dari tarikh tamat sewaan yang dinyatakan di SEKSYEN 5(c) di JADUAL Perjanjian ini dengan memberikan NOTIS AWAL TIGA PULUH (30) HARI SECARA BERTULIS kepada Penyewa tanpa perlu menyatakan sebarang sebab. Tuan Tanah tidak akan bertanggungjawab terhadap sebarang kerugian, kehilangan atau kesulitan yang mungkin dialami oleh Penyewa akibat penamatan tersebut."

[Emphasis Added]

[39] This cl 4(h) was continued as part of the 1st Tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land when it was renewed to an extended period of 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019: see the extension letter in AB1/76 - 77 (encl 41).

[40] Under cl 4(h) of the 1st Tenancy Agreement, the defendant-landlord is entitled to terminate by giving a written notice of 30 days and there is no necessity to give any reason.

[41] By Notice of Termination dated 26 April 2018 issued by the defendant-landlord to the plaintiff-tenant, the defendant notified the plaintiff of the termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 1st Land (Tapak Tempat Letak Kenderaan) with effect from 31 May 2018 and asked the plaintiff to vacate the 1st Land by 31 May 2018 [AB1/463 (encl 42)]. This issuance and service of the Notice of Termination dated 26 April 2018 is a common fact accepted by the witnesses of both parties.

[42] This Notice of Termination dated 26 April 2018 has given more than 30 days' notice in writing to the defendant. As such, the Notice of Termination has complied with the termination procedure as stipulated in cl 4(h) of the 1st Tenancy Agreement, and the termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement was expressly allowed by cl 4(h) theroef.

[43] Although the plaintiff's witnesses seemed to harbour an initial misapprehension that there was one (1) single notice of termination for two (2) separate tenancy agreements, the existence of two (2) separate Notices of Termination, one for each tenancy agreement, was not disputed by the plaintiff after exhs D1(a)" and "D1(b)" in encl 40 were adduced in evidence at the trial. From the evidence adduced, this Court finds it was clearly proven that there were two (2) separate Notices of Termination, one for each tenancy agreement.

[44] In the circumstances the defendant's termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land is valid and not wrongful.

Issue 2: Whether The Termination Of The 2nd Tenancy Agreement (Tapak Gerai) Is Wrongful?

[45] In the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land, there is no clause on early termination by the defendant-landlord before the expiry of the tenure of tenancy.

[46] Clause 7.1(a) of the latest version of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement dated 9 June 2017 provides that the landlord is entitled to terminate the tenancy in the event of default by the tenant: see AB1/128 -161 @ 140 - 141 (encl 41). Clause 7.1(b) of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement provides for immediate termination of the tenancy upon the insolvency or winding-up of the tenant: AB1/141 (encl 41). Clause 7.1(c) of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement provides that the tenant may terminate the tenancy of the 2nd Land by giving to the landlord 90 days of advance notice: see AB1/141 (encl 41). Under cl 7.1(c) of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement, the right of early termination was given to the plaintiff-tenant and not to the defendant-landlord.

[47] Although cls 7.1(a) and 7.1(b) in the 2nd Tenancy Agreement stipulated termination by the landlord in the event of default or insolvency of the tenant, the defendant has not relied upon nor adduced evidence of any evidence of any default or insolvency.

[48] The 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land (Tapak Gerai) was extended until 31 December 2019: see 2nd Tenancy Agreement dated 9 June 2017 in AB1/128 - 161 (encl 41).

[49] The Notice of Termination dated 27 April 2018 ["Exhibit D1(a)" and "D1(b) in encl 40"] issued by the defendant-landlord to the plaintiff-tenant, which purported to give notice of early termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land (Tapak Gerai) with effect from 31 May 2018, is therefore issued in breach of the contract and is wrongful.

[50] This Court rejects the defendant's argument that the termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement by the defendant was justified by reason of the 2nd Land being required for a public purpose.

[51] Public purpose is legal justification for compulsory acquisition of lands by a public authority, but it is not a valid and sufficient ground for the landlord's premature termination of a tenancy in the absence of an express contract clause for such early termination upon occurrence of such event. Where a land is compulsorily acquired under the Land Acquisition Act or is being required for a public purpose, the landlord who has to prematurely terminate the tenancy of the land with his tenant has to pay damages for premature termination to his tenant and, by reason thereof, the landlord has a right to include the damages payable to his tenant as a head of claims for compensation from the acquisition authority. The tenant's right to get damages for premature termination can only be extinguished if the tenant has been directly compensated by the land acquisition authority for such premature termination of tenancy, as the law does not allow double recovery by the tenant.

[52] In our present case, the plaintiff-tenant has not been compensated and will not be compensated by the public authority who took over the 1st Land for the purpose of the public transportation project. See PW3 Ching Kian Hwa's evidence in WS-PW3 Q&A 44 - 48, 53-58 (encl 46). None of the defendant's witnesses has alleged or shown that the plaintiff was or would be paid land acquisition compensation by the acquisition authority. According to the defendant's witness, as the said lands were held by the State Government as the registered proprietor, there was no acquisition necessary for the use of the said land for public purpose and therefore there was no question of any land acquisition compensation to either the plaintiff or the defendant.

[53] In the premises, the plaintiff-tenant does not lose its right to claim damages from the defendant-landlord for premature termination of tenancy arising from the requisition of the 1st Land for the public transportation project and the award of such damages for wrongful termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement does not entail any double recovery.

[54] This Court also rejects the defendant's argument that the termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement by the defendant was justified by reason of acquiescence on the part of the plaintiff. In the circumstances of the present case this Court agrees with the plaintiff's submission that the plaintiff has not by its acts or conduct acquiesced in the premature termination by the defendant. What the plaintiff did was to give the cooperation to the defendant for peaceful and orderly evacuation from the lands as was expected of a law-abiding tenant. The plaintiff has not in any way given away or abandoned its legal rights in relation to the premature termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement. As the lands were urgently required for the public purpose of constructing a station for the Park N Ride project, the plaintiff acted lawfully and reasonably in not opposing the intended construction works and therefore the plaintiff cannot be unjustly be held to have acquiesced a wrongful termination. Neither has the plaintiff accepted as valid the premature termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in the circumstances of this case.

Issue 3: Whether The defendant Has Misrepresented To The Plaintiff That The defendant Was The Registered Proprietor Of The 1st Land And The 2nd Land?

[55] In our present case the plaintiff-tenant also made an issue regarding the alleged misrepresentation on the part of the defendant-landlord and based upon such allegation, the plaintiff-tenant has claimed for refund of all the rental payments paid to the defendant-landlord over the past many years.

[56] PW3 Ching Kian Hwa testified that the defendant-landlord's alleged misrepresentation was in representing that the defendant-landlord was the registered proprietor of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land: see WS-PW3 Q&A 11 and 12.

Peaceful Occupation And Estoppel Against Denial Of Landlord's Title

[57] In the first place, the plaintiff in our present case enjoyed peaceful and undisturbed occupation and possession of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land through the years of tenancy since 2008 until end May 2018, the date of taking effect of the termination. Through all those years, there was no disturbance, interference or adverse claim by any other third person or entity which in any way adversely affected the plaintiff's use, occupation and enjoyment of the 1st Land and 2nd Land for parking its lorries, containers and motor vehicles.

[58] In a tenancy agreement, the substance of the transaction is that the tenant should enjoy a peaceful and undisturbed occupation and possession of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land throughout the tenure of tenancy and in exchange, the landlord should receive the rentals from the tenant. In our present case, the substance of the tenancy was fulfilled and enjoyed by both parties respectively.

[59] Under the legal maxim jus tertii, in a suit for eviction or trespass, a tenant is barred from questioning the title of the landlord in the absence of an adverse claim for title by a third legal entity.

[60] Analogous to or similar to the effect of such maxim, s 116 of our Evidence Act 1950 estops a tenant from denying or questioning the landlord's title to possession. Section 116 of our Evidence Act provides as follows:

"Estoppel of tenant and of licensee of person in possession

116. No tenant of immovable property, or person claiming through the tenant, shall during the continuance of the tenancy be permitted to deny that the landlord of that tenant had at the beginning of the tenancy a title to the immovable property; and no person who came upon any immovable property by the licence of the person in possession thereof shall be permitted to deny that that person had a title to such possession at the time when the licence was given."

[61] As the facts of our present case clearly establish a landlord-tenant relationship between the defendant and the plaintiff for about 10 years in respect of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land, the s 116 statutory estoppel applies to our present case here.

[62] In the premises, this Court accepts the defendant's submission that the plaintiff-tenant is estopped from denying that the defendant-landlord has the title as the landlord to the 1st Land and the 2nd Land: see s 116 of the Evidence Act 1950.

[63] In view of the above, the plaintiff-tenant's allegations on misrepresentation against the defendant-landlord is of no legal consequence or factual relevance here. In the circumstances, the plaintiff-tenant cannot deny that the defendant-landlord has a title or lawful right to rent out the said lands to the plaintiff-tenant and to collect rentals in respect of the tenancies. Moreover, the plaintiff-tenant enjoyed peaceful occupation and use of the said lands over the many years of the tenancies. On this ground alone, the plaintiff- tenant's claim for refund of the rental payments should be dismissed.

Defendant's Authority To Let

[64] In the second place, the evidence adduced in the present case shows that the 1st Land and the 2nd Land were originally part of the developer's land which was approved for development into the Bukit Raja Prime Industrial Park and that as part of the authorities' approval for the development of a project here, the developer agreed to surrender the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to the State Authority as part of the public areas. The titles of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land were registered in the name of Kerajaan Negeri Selangor. See AB1/633 (encl 42); Exhibit "DS" (in A3 size); Exhibit "D91" (in AO size).

[65] This Court accepts the defendant's evidence that the State Authority has allocated and/or given the rights in respect of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to the defendant, the local authority in charge of the District of Alam where the project and the lands are located. See AB1/633 (encl 42); Exhibit "D8" (in A3 size); Exhibit "D9" (in AO size); DW2 Aniza's evidence on 18 April 2022, WS-DW2 Q&A 8 - 10; Exhibit "D9" in AO size; AB1/632 - 633 (encl 42).

[66] Interpretation of the terms of the contract is a question of law for the Court to decide.

[67] A witness' evidence as to the interpretation of the terms of contract is not relevant and is not binding upon the Court or the parties to the suit (including the party who called the witness to attend court) save in very exceptional circumstances when it becomes relevant where a word is a scientific term or has a special meaning in a particular trade or usage. Our present case does not fall within any of such exceptional circumstances regarding evidence of witness in the interpretation of contract terms or legal terms.

[68] Interpretation of contract terms being a question of law, a party's admission or a witness' evidence on on a point of law, including the meaning of contract terms, is not relevant and does not bind the party or the Court: see the decisions in Guan Soon Tin Mining Co v. Ampang Estate Ltd [1972] 1 MLRA 125 (Federal Court) and Rethnasamy v. Teoh Ngoo Mooi & Anor [1982] 1 MLRH 753. Per Ong CJ in Guan Soon Tin Mining: I do not think this letter written by laymen having no knowledge of the law should be read as an unconditional admission binding on them regardless of their mistaken view of the law. If they were in error, their error cannot oblige the Court to follow their view."

[69] The plaintiff argues that the defendant as a local government has no authority to earn rentals from the 1st Land and the 2nd Land and that the defendant's collection of rentals from the plaintiff was allegedly illegal.

[70] The provisions of the Local Government Act 1976 include the following sections:

"13. Every local authority shall be a body corporate and shall have perpetual succession and a common seal which may be altered from time to time, and may sue and be sued, acquire, hold and sell property and generally do and perform such acts and things as bodies corporate may by law do and perform.

19. Every local authority shall provide an office within the local authority area for the transaction of business.

36. (1) A local authority may enter into contracts necessary for the discharge of any of its functions provided that such contracts do not involve any expenditure in that year in excess of the sums provided in the approved annual estimates for the discharge of such functions, unless such expenditure in that year is authorised under s 56.

39. The revenue of a local authority shall consist of:

(a) all taxes, rates, rents, licence fees, dues and other sums or charges payable to the local authority by virtue of the provisions of this Act or any other written law;

(b) all charges or profits arising from any trade, service or undertaking carried on by the local authority under the powers vested in it;

(c) all interest on any money invested by the local authority and all income arising from or out of the property of the local authority, movable and immovable; and

(d) all other revenue accruing to the local authority from the Government of the Federation or of any State or from any statutory body, other local authority or from any other sources such as grants, contributions, endowments or otherwise".

[71] The word "rents" is not defined in the Local Government Act 1976. The Court of Appeal in Ban Kok Hotel v. Low Phek Choon [1950] 1 MLRA 576 explained the meaning of "rents" as follows:

The word "rental" is not defined under the said Act. The then Court of Appeal in Ban Kok Hotel v. Low Phek Choon [1950] 1 MLRA 576 (refer: TAB-C PBOA) had defined rental in the following manner:

"The primary meaning of "rent" is given in Stroud's Judiciary Dictionary (2 edn 1710) as:

"The sum certain, in gross, which a tenant pays his landlord for the right of occupying the demised premises."

"Wharton's Law Lexicon (14th edn 866) gives this definition "A certain profit issuing yearly out of lands and tenements corporeal."

The Concise Oxford English Dictionary gives the following primary meaning:

"Tenant's periodical payment to owner or landlord for use of land or house or room."

[72] In light of the provisions of the Local Government Act 1976 and the natural and ordinary meaning of "rents", this Court does not see any legal objection against the local authority's signing of a tenancy contract for renting out part of the open space within the local authority area and collecting a rental or income from such renting out.

[73] More so, the defendant-local authority's renting out of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to the plaintiff was originally due to the plaintiff's indiscriminate or unauthorised parking of its containers and lorries at the car parking bays at the office area which were not meant for containers and lorries, and the defendant's offer of alternative lands at a very low initial rental of RM1,000 per month per land plot of about 0.5 acre each was to avoid or alleviate the problem of such parking of containers and lorries at car parking bays meant for cars and light vehicles. Control and regulation of parking of motor vehicles at public parking bays is one of the functions of a local authority. In the context of the present case, the defendant's renting out of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to the plaintiff flowed directly from or was incidental to the defendant's administration of the relevant part of the local authority area, and it is not a purely commercial transaction as such.

[74] It is also to be noted that apart from the express powers and authorities conferred by the Local Government Act 1976, there are also other written laws which empower the local authority to earn other types and forms of income including rentals and sale proceeds from properties in a development area it has developed: s 43 of Town and Country Planning Act 1974. It is a well-settled practice that all local authorities collect rentals and/or parking fees from carparking bays which were surrendered by the developers to the State Governments and/or local authorities.

Any Misrepresentation As To Authority To Let

[75] Thirdly, in the context of the agreements and the factual matrix, this Court agrees with the defendant's submission that there was no material misrepresentation by the defendant that the defendant was the "registered proprietor" of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land.

[76] In the context of sale and purchase agreement, representation as to "registered proprietor" and "beneficial owner" is a material representation, as only the registered proprietor and/or the beneficial owner has the lawful authority to sell the land. In the context of tenancy agreement, representation as to the lawful authority to rent out the land is a material representation, as persons other than the registered proprietor and beneficial owner can have the lawful authority to rent out the land. Persons other than the registered proprietor and beneficial owner but have the lawful authority to rent out the land include the lessee, chief tenant, custodian of land, or any other person who has been authorised by the registered proprietor or beneficial owner to rent out the land. As long as the landlord has the lawful authority to rent out the land, it is immaterial whether or not he is also the registered proprietor or beneficial owner of the land.

[77] During the cross-examination on 28 March 2022, PW3 Ching Kian Hwa was referred to various parts of the tenancy agreements in AB1/7 ("Tuan Tanah"), AB1/ 56 ("Tuan Tanah"), AB1/81 ("Majlis"), AB1/89 ("Tuan Tanah"), AB1/110 ("Tuan Tanah") and he confirmed that the term "Pemilik Berdaftar" (registered proprietor) was not used in the tenancy agreements. During the re-examination on 28 March 2022, the plaintiff's Counsel also referred PW3 to AB1/15 and AB1/36 which contained the recital to the Tenancy Agreement to the effect that Tuan Tanah adalah pemilik berdaftar atau pemilik benefisial".

[78] The word "Tuan Tanah" which appears in a number of the versions of the tenancy agreement and the extension agreements means "landlord" and not "registered proprietor" unless the context otherwise requires.

[79] This Court accepts the evidence of the defendant's witnesses that (a) when the defendant in its capacity as the municipal council approved the building plan for the Bukit Raja Prime Industrial Park, the 1st Land and the 2nd Land were among the land parcels which were required to be surrendered by the developer to the local government [DW2 Aniza's evidence on 18 April 2022; WS-DW2 Q&A 8 - 10; Ekshibit "D9" in AO size; AB1/632 - 633 (encl 42)]; (b) pursuant to the building plan approval, the developer indeed surrendered the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to the local government and the said lands were registered in the name of the State Government of Selangor [DW1 Khairoul Nisya's evidence on 18 April 2022 in WS-DW1 Q&A 20 (encl 45)]; (c) although the transfer of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to the defendant-landlord has not been perfected, the 1st Land and the 2nd Land have been allocated by the State Authority to the defendant, the municipal council in charge of the Municipality of Shah Alam, for the defendant to use and/or to develop and the defendant had lawful authority to rent out the said lands [DW1 Khairoul Nisya's evidence on 18 April 2022 in WS-DW1 Q&A 21, 31; DW2 Aniza's evidence on 18 April 2022; WS-DW2 Q&A 16]; (d) the plaintiff in its discussions with the defendant's officers had knowledge that the said lands were State Government lands which were permitted to be used and/or developed by the defendant [DW1 Khairoul Nisya's evidence on 18 April 2022 in WS-DW1 Q&A 23].

[80] With the allotment by the State Authority to the defendant, the defendant became the beneficial owner of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land and/or had the lawful authority to manage, rent out and collect rentals from the 1st Land and the 2nd Land. In the circumstances of the present case it is not erroneous to state that the defendant, in its capacity as the local authority in charge of Shah Alam area, is in a sense, a beneficial owner of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land.

[81] This Court also accepts the defendant's submission that a person who is not the registered proprietor of land can be the lawful landlord of the land. Examples include lessee, chief tenant, land custodian, licensee or a person having lawful possession or occupation of the land.

[82] Under the Town and Country Planning Act 1976 the local authority has the authority to require that a developer who applies for planning approval for a project is to set aside open space to be surrendered to the government for public purpose. The local government set up by the State Government under the Local Government Act 1976 is in charge of the administration of the local authority area: s 3. The affairs of every local authority area are administered by a local authority: s 8. In the premises, this Court does not see any legal obstacles to the defendant, as a local authority in charge of the affairs in the Alam local authority area, to rent out temporarily any public area or open space within its local authority area which belongs to the State Government.

[83] In the circumstances, the defendant here at all material times could be the lawful landlord in respect of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land. Even if the defendant had made any misrepresentations as to its status as "registered proprietor" or "beneficial owner" as alleged by the plaintiff, this did not affect the defendant's capacity as landlord to lawfully rent out the said lands to the plaintiff.

[84] Even if there was any misrepresentation as to "registered proprietor" as alleged, such alleged misrepresentation did not cause any loss or damage to the plaintiff. The plaintiff has had the full enjoyment of peaceful use and occupation of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land for about 10 years until the termination of the tenancies in mid-2018. If the defendant-local authority did not rent out the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to the plaintiff in 2005, the plaintiff would have to find another site to park its containers and lorries, and the rentals or periodical payments for the alternative site is unlikely to be less than the low rentals charged by the defendant in respect of the 1st Land and the 2nd Land from 2005 to mid-2018.

[85] In the circumstances, this Court rejects the plaintiff's claim of misrepresentation and claim for refund of the rental payments.

Undue Influence

[86] This Court also rejects the plaintiff's allegation of undue influence. This allegation of undue influence has not been specifically pleaded in the Statement of Claim and also has not been proven in evidence. [see encl 32]

Unjust Enrichment

[87] Firstly, the plaintiff did not specifically plead the elements or material facts for a cause of action on unjust enrichment in the Statement of Claim [see encl 32], and is therefore not allowed to claim any recovery on the basis of unjust enrichment. See Simcity-Ete Venture Sdn Bhd v. Koperasi Pembangunan Kampung Tradisional Tasek Pulau Pinang Berhad [2022] 2 MLRA 472.

[88] Secondly, the plaintiff-tenant enjoyed peaceful possession of the lands for years and operated its businesses with the benefits of using the said lands. By collecting a rental of RM4,000 per month for each parcel of vacant land of size 0.5 acre or RM0.19 psf per month [see exh "D9" in A0 size] in the heart of a developed industrial park within the Klang town area and by allowing the plaintiff-tenant to enjoy peaceful and undisturbed occupation and use of the said lands, the defendant-landlord merely received its just and rightful entitlement to rentals and has not been enriched at the expense of the plaintiff-tenant. There was therefore no enrichment to the defendant at the expense of the plaintiff.

[89] Thirdly, it is not unjust for the defendant to keep the rentals collected, as the plaintiff-tenant enjoyed peaceful possession of the lands for years and operated its businesses with the benefits of using the said lands. In our present case, there is no allegation or evidence whatsoever that the State Government as the registered proprietor has claimed or will claim any rental from the plaintiff-tenant in connection with the plaintiff-tenant's occupation or use of the said lands over the past years. If there is another legal entity who, as alleged by the defendant, is the registered proprietor who should get the rental incomes, then in the eyes of the law it is for that other legal entity who asserts its registered proprietorship to claim against the defendant-landlord for the rental collections - res inter alios. For the plaintiff-tenant to have enjoyed peaceful possession of the lands for years and operated its businesses with the benefits of using the said lands and then to get the total refund of the rentals paid for using and occupying the lands is to unfairly and unjustly enrich the plaintiff-tenant. There has been no unjust enrichment of the defendant-landlord at the expense of the plaintiff-tenant.

Summing Up On Issue 3

[90] Any one of the abovementioned three reasons is sufficient for dismissing the plaintiff's claims on unjust enrichment.

[91] In the premises, this Court dismisses the plaintiff's claim for RM576,220.00 for the purported refund of the rentals collected.

Issue 4: Whether The Plaintiff Is Entitled To Its Claims Or Any Part Thereof

[92] As stated above, this Court has dismissed the plaintiff's refund claim of RM576,220.00. Prayer (d) in para 29 of the Statement of Claim is dismissed.

[93] This Court holds that the defendant's termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land is lawful and valid, and therefore this Court dismisses prayer (a) in para 29 of the Statement of Claim.

[94] This Court holds that there is no valid basis for the plaintiff to challenge the validity and legality of the 1st Tenancy Agreement and the 2nd Tenancy Agreement, and therefore this Court dismisses prayer (c) in para 29 of the Statement of Claim.

[95] As regards prayer (aa) in para 29 of the Statement of Claim, this Court holds that the purported termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land was premature and wrongful. However, this Court finds the wording of prayer (aa) to be improper or inappropriate. As such, instead of prayer (aa), this Court hereby declares that the purported termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land was premature and wrongful.

[96] As regards prayer (b) in para 29 of the Statement of Claim, this Court holds that the plaintiff is only entitled to claim for losses and damages which were caused by the wrongful termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land in accordance with s 74 of the Contracts Act 1950. The findings and assessment of such losses and damages are dealt with under a separate heading below.

[97] This Court finds that the reason relied upon by the defendant for termination of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land was that the 2nd Land was required for the public purpose of construction of a station for the Park N Ride project. This is a bona fide reason and for a public purpose. There are no aggravating circumstances or oppressive act or conduct on the part of the defendant in having to prematurely terminate the 2nd Tenancy Agreement in respect of the 2nd Land. In the circumstances, this Court does not find any valid or sufficient basis for awarding exemplary damages or punitive damages against the defendant in the present case. As such, prayer (e) in para 29 of the Statement of Claim is dismissed.

[98] In opposing the plaintiff's heads of claims for damages, the defendant has argued that the structures at the 1st Land and the 2nd Land were built or continued without the approval of the defendant: see DW3 Noraidah's evidence in WS-DW3 Q&A 4 to 12 (encl 72).

[99] This Court accepts the plaintiff's evidence that the structures at the said lands were approved for construction by the defendant before the plaintiff constructed them: see the evidence of PW3 Ching Kian Hwa WS-PW3 Q&A 1 & 2 (encl 70) and the approved plans for the structures in exhs "P5(a)", to:"P5(i) in encl 66 pp 1-11. This Court does not accept the defendant's argument that where a land was rented from the municipal council with the structures built according to the permit and approval of the municipal council, the law still requires an extreme hair-splitting condition that for each extension of the tenancy granted by the same municipal council, the tenant still had to obtain afresh the municipal council's separate permit or approval for the continuation of the previously- approved structures on the land.

[100] With the official extension granted by the defendant, there was no necessity to resubmit for the continuation of the constructed structures each time the tenancy was extended. A landlord's agreement to extend the pre-existing tenancy period necessarily include the landlord's consent or approval for the continuation of the pre-existing structures at the demised land during the duration of the extended tenancy.

Assessment Of Losses And Damages For Wrongful Termination Of The 2nd Tenancy Agreement

[101] It is settled law that in order to recover losses and damages for breach of contract, the plaintiff has to prove he has incurred losses and damages as well as that the losses and damages were caused by the said breach. The causal link between the breach of contract and the head of damages must be proved by the plaintiff on a balance of probabilities.

[102] The necessity to prove the causal link between the breach of contract and the damages and the ambit of recoverable damages have been reiterated by our Court of Appeal in the recent case of Guinness Anchor Marketing Sdn Bhd v. Man Seng Trading & Marketing Sdn Bhd [2021] MLRAU 237 in the following words:

"[58] In respect of the principles on assessment of damages, the Supreme Court case of Eikobina (M) Sdn Bhd v. Mensa Mercantile (Far East) Pte Ltd [1994] 1 MLRA 146 provided guidance as follows:

After liability on a contract is established and when it comes to assessment of damages, two questions are always involved. The first is that no compensation can be awarded for damage that is too remote and the second is that in assessing damage that is not too remote, the correct measure of damages must be adopted, ie, the correct and usual principles of quantifying the monetary compensation must be employed.

The Courts have long recognised that a contract breaker could not be liable for all consequences which flow naturally from a breach of contract and that they must draw a line somewhere, otherwise the consequences would be, inter alia, ruinous to the contract breaker. Thus, certain of such ensuing consequences would be regarded as too remote to be claimable, 'not perhaps on grounds of pure logic but simply for practical reasons', to quote a dictum of Lord Wright in Liesbosch Dredger v. Edison SS made in a similar vein.

The meaning of remoteness of damage was finally settled in the landmark case of Hadley v. Baxendale as follows:

When two parties have made a contract which one of them has broken, the damages which the other party ought to receive in respect of such breach of contract should be such as may be fairly and reasonably considered either arising naturally, ie, according to the usual course of things from such breach of contract itself or such as may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of both parties, at the time they made the contract, as the probable result of the breach of it ...

[59] The rule in regard to remoteness of damage enunciated in Hadley v. Baxendale is found in s 74 of the Contracts Act 1950. Section 74 provides that:

74. Compensation for loss or damage caused by breach of contract

(1) When a contract has been broken, the party who suffers by the breach is entitled to receive, from the party who has broken the contract, compensation for any loss or damage caused to him thereby, which naturally arose in the usual course of things from the breach, or which the parties knew, when they made the contract, to be likely to result from the breach of it.

(2) Such compensation is not to be given for any remote and indirect loss or damage sustained by reason of the breach.

[60] Based on this principle, the respondent's claim for damages must fall within either limb, in particular it must not be too remote. There must be a causal link shown between the breach complained of (which is the termination in this case) and the loss claimed. As the respondent's cause of action was premised on breach of contract, the measure of damages for such cause of action is that the respondent should be put in a position as if the distributorship agreement had been performed, and not any better. The respondent cannot be put in a better position than if there was no breach.

[61] This principle is explained by the of Federal Court in Bank Pertanian Malaysia Bhd v. Koperasi Permodalan Melayu Negeri Johor [2015] 6 MLRA 297, in these terms:

[100]... In the circumstances of the case, all that the Koperasi is entitled to is to be put in a position as if the breach had not occurred. If the breach had in any way resulted loss to the Koperasi, damages would have to be assessed, so far as money could do so, to compensate the Koperasi by placing it in the same position as if the breach had not occurred.

[101] The above proposition was adopted by Parke R in Robinson v. Harman [1843 - 60] All ER Rep 383 at p 385 when he said 'where a party sustains a loss by reason of a breach of contract, he is, so far as money can do it, to be placed in the same situation with respect to damages, as if the contract had been performed'. If the Koperasi is to be put in a better position than it would have been if there had been no breach by the bank in prematurely uplifting the fixed deposit, then it would be contrary to the principle enunciated in established authorities (see Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat & Anor v. Plenitude Holdings Sdn Bhd [1994] 1 MLRA 420; Koufos v. C Czarnikow Ltd [1969] 1 AC 350; and Hadley v. Baxendale (1854) 9 Ex 341; 156 ER 145).

[62] The respondent must prove actual loss for each and every head of claim and if actual loss is not proven, then the claim ought to be dismissed or only nominal damages could be granted. This well- established principle was recently restated by the Court of Appeal in Perbadanan Kemajuan Negeri Selangor v. Selangor Country Club Sdn Bhd [2017] 1 MLRA 46, where it held that:

[51] As to damages, it is settled law that in order for SCCSB to succeed in its claim SCCSB must show that the loss and damages is due to the breach of contract by PKNS. Once that is established, SCCSB has the additional burden of proving the damages. The law on the recovery of damages has been succinctly enunciated by Ramly Ali J (now FCJ) in PB Malaysia Sdn Bhd v. Samudra (M) Sdn Bhd [2008] 6 MLRH 841 at 855. It may be summarised into two main principles:

(a) the burden of proof is on the party seeking the claim to prove the facts and the amount of damages (Hock Huat Iron Foundry (suing as a firm) v. Naga Tembaga Sdn Bhd [1998] 2 MLRA 356); Bonham- Carter v. Hyde Park Hotel Ltd (1948) 64 TLR 177; Popular Industries Limited v. Eastern Garment Manufacturing Sdn Bhd [1989] 2 MLRH 705 635 and Sony Electronics (M) Sdn Bhd v. Direct Interest Sdn Bhd [2006] 2 MLRA 583;

(b) the damages must be proved with real or factual evidence. Mere particulars, summaries, estimations or general conclusions will not suffice (Lee Sau Kong v. Leow Cheng Chiano [1960] 1 MLRA 302 (CA)).

[63] In our considered view, these are the three key principles of law that the DR and High Court Judge must adhere to and apply in assessing the respondent's claim for damages. Failure to do so would be plainly wrong and would render the finding or decision made untenable at law."

[103] In the following paragraphs of this Court's judgment, this Court will assess and evaluate the plaintiff's heads and amounts of claims for losses and damages in accordance with the legal principles stated by the Court of Appeal in the immediately-foregoing paragraph.

[104] The breach of contract in our present case is the premature termination of the contract in April 2018 ahead of the expiry of the tenancy at the 2nd Land on 31 December 2019

[105] Item 1 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM100,000 as the costs of improving the lands with crusher run and levelling and compaction:

This head of claim is rejected because:

(a) This costs of crusher run and levelling and compaction was incurred at the early stage of the tenancies when the plaintiff wanted to use the said lands [see exh "P7(a)" at p 23 of encl 66 and PW3's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022], which were originally covered with trees, for its parking of the lorries, containers and motor vehicles. Such improvement cost was incurred irrespective of whether tenancy was terminated or allowed to expire at the end of its tenure. Moreover, it is improper to claim the full cost of constructing this item of structure when in actual fact the plaintiff-tenant had enjoyed the use and benefit of this item for more than 10 years. The plaintiff-tenant has not given any evidence as to the fair and reasonable residual value of this item after having used it for more than 10 years.

(b) There is no evidence that the laid crusher run could be economically excavated from the 1st Land and the 2nd Land, transported to and re-used at the plaintiff's new site and with cost saving compared with the similar site preparation works at the new site. As such, on a balance of probabilities this head of cost would have been incurred and the crusher run would still be left behind at the 1st Land and the 2nd Land even if the 2nd Tenancy Agreement was allowed to continue until 31 December 2019; irrespective of whether the tenancy was terminated earlier or allowed to expire at its end, the crusher run which had already been laid, levelled and compacted at the said lands long before May 2018 would still be left behind at the said lands.

(c) The plaintiff has not given specific evidence as to which land (whether 1st Land or 2nd Land or both) were improved with crusher run, and as the 1st tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land was lawfully terminated, the plaintiff cannot claim for any cost or loss in respect of the termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement.

[106] Item 2 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM60,000 as cost of chainlink fencing and 2 steel doors:

This head of claim is rejected because:

(a) This chainlink fencing cost was incurred at the early stage of the tenancies at the end of 2005 when the plaintiff first wanted to use the said lands [see exh "P7(b)" at p 24 of encl 66 and PW3's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022], which were originally covered with trees, for its parking of the lorries, containers and motor vehicles. Such improvement cost was incurred irrespective of whether tenancy was terminated or allowed to expiry at the end of its tenure Moreover, it is improper to claim the full cost of constructing this item of structure when in actually fact the plaintiff-tenant had enjoyed the use and benefit of this item for more than 10 years. The plaintiff-tenant has not given any evidence as to the fair and reasonable residual value of this item after having used it for more than 10 years.

(b) The plaintiff has not given evidence that the defendant or another person has prevented the plaintiff from dismantling the chainlink fencing and transport to and re-use it at the plaintiff new site.

(c) The plaintiff has not given evidence that if the 2nd Tenancy Agreement were allowed to expire on 31 December 2019 instead of prematurely terminated in May 2018 the plaintiff would be able to save costs of chainlink fencing construction at the new site.

(d) The plaintiff has not given specific evidence as to which land (whether 1st Land or 2nd Land or both) were fenced up with chainlink fencing, and as the 1st tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land was lawfully terminated, the plaintiff cannot claim for any cost or loss in respect of the termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement.

[107] Item 3 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM4,000; steel frame.

This item is rejected because:

(a) This steel frame cost was incurred at the early stage of the tenancies in end 2005 when the plaintiff first wanted to use the said lands [see Exhibit "P7(c)" at p 25 of encl 66 and PW3's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022], which were originally covered with trees, for its parking of the lorries, containers and motor vehicles. Such improvement cost was incurred irrespective of whether tenancy was terminated or allowed to expire at the end of its tenure. Moreover, it is improper to claim the full cost of constructing this item of structure when in actually fact the plaintiff-tenant had enjoyed the use and benefit of this item for more than 10 years. The plaintiff-tenant has not given any evidence as to the fair and reasonable residual value of this item after having used it for more than 10 years.

(b) The plaintiff has not given evidence that the defendant or another person has prevented the plaintiff from dismantling the steel frame and transport to and re-use it at the plaintiff new site. The plaintiff has not given evidence that if the 2nd Tenancy Agreement were allowed to expire on 31 December 2019 instead of prematurely terminated in May 2018, the plaintiff would be able to save costs of steel frame construction at the new site.

(c) The plaintiff has not given specific evidence as to which land (whether 1st Land or 2nd Land or both) was the steel frame located, and as the 1st tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land was lawfully terminated, the plaintiff cannot claim for any cost or loss in respect of the termination of the 151 Tenancy Agreement.

[108] Item 4 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM40,800 as steel structure garage and concrete floor:

This item was rejected because:

(a) This costs of steel structure garage and concrete floor were incurred at the early stage of the tenancies at the end of 2005 when the plaintiff first wanted to use the said lands [see exh "P7(d)" at p 26 of encl 66 and PW3's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022], which were originally covered with trees, for its parking of the lorries, containers and motor vehicles. Such improvement cost was incurred irrespective of whether tenancy was terminated or allowed to expire at the end of its tenure. Moreover, it is improper to claim the full cost of constructing this item of structure when in actually fact the plaintiff-tenant had enjoyed the use and benefit of this item for more than 10 years. The plaintiff-tenant has not given any evidence as to the fair and reasonable residual value of this item after having used it for more than 10 years.

(b) There is no evidence that the concrete floor could be economically excavated for the 1st Land and the 2nd Land, transported to and re-used at the plaintiff's new site and with cost saving compared with the similar site preparation works at the new site. As such, on a balance of probabilities this head of cost would have been incurred and the concrete floor would still be left behind at the 1st Land and the 2nd Land even if the 2nd Tenancy Agreement was allowed to continue until 31 December 2019; irrespective of whether the tenancy was terminated earlier or allowed to expire at its end, the concrete floor which had already been cast at the said lands long before May 2018 would still be left behind at the said lands.

(c) The plaintiff has not given evidence that the defendant or another person has prevented the plaintiff from dismantling the steel structure and transporting to and re-using it at the plaintiff new site.

(d) The plaintiff has not given evidence that if the 2nd Tenancy Agreement were allowed to expire on 31 December 2019 instead of prematurely terminated in May 2018, the plaintiff would be able to save costs of steel structure garage construction at the new site.

(e) The plaintiff has not given specific evidence as to which land (whether 1st Land or 2nd Land or both) was the steel structure garage and concrete floor and, and as the 1st tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land was lawfully terminated, the plaintiff cannot claim for any cost or loss in respect of the termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement.

[109] Item 5 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM4,000: store made of steel frame:

This item is rejected on the same reasons as for item 3 (the steel frame), [see exh "P7(e)" at p 27 of encl 66 and PW3's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022]

[110] Item 6 of the plaintiff s alleged loss/damages: RM6,400: toilet with brickwails.

This item is rejected on the same reasons as for item 1 (crusher run), [see exh "P7(f)" at p 28 of encl 66 and PW3's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022]

[111] Item 7 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM1,750: guardhouse.

This item is rejected on the same reasons as for item 1 (crusher run), [see exh "P7(g)" at p 29 of encl 66 and PW3's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022]

[112] Item 8 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM60,000 as shifting costs.

This item on cost of shifting would be recoverable to the extent where the plaintiff can prove that the cost of shifting in May 2018 or mid 2018 (the end date given in the Notice of Termination) was higher than the cost of shifting in end December 2019 (the expiry of the tenure of tenancy by effluxion of time). However, the plaintiff here did not adduce evidence to this effect.

What the plaintiff claims here is the total cost of shifting its parking facility and parking operations from the 1st Land and the 2nd Land in Bukit Raja to the new site in Kapar: see exh. "P4" at p 10 of encl 66 and PW3 Ching Kian Hwa's evidence in WS-PW4(b) Q&A4 on 18 April 2022. This in principle is not the correct manner of computing such loss claim. It is undeniable that that whether the shifting took place in May 2018 or in December 2019, there would still be costs incurred for the shifting. The plaintiff's loss for having to shift earlier is the differential amount of the shifting costs at two different times if the shifting costs in May 2018 were comparatively higher than the shifting costs in December 2019.

As the plaintiff has not produced evidence to prove that it would have a saving or reduction in the costs of shifting if the shifting were to take place in December 2019 (the expiry date of the 2nd Tenancy Agreement) instead of in mid 2018 (the date of shifting due to termination), this Court has no evidential basis to award any amount for this head of claim.

[113] Item 9 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM96,000.00 as the costs of 12 months of temporary renting of site.

This head of claim is a valid claim because the premature and wrongful termination of the 2nd Land would have caused the necessity to rent a temporary site at short notice for the parking of the lorries, containers and motor vehicles which could otherwise be parked at the 2nd Land. The temporary rental costs are substantiated by the invoices and receipts produced in evidence at the trial: see PW3 Ching Kian Hwa's quantum evidence on 18 April 2022, WS-PW3(b) in encl 70, AB2/1 - 11 (encl 68) and Exhibits "P6(a)" to "P6(l)" in encl 66 pp 11 - 22.

However, since only the termination of the 2nd Land is held by this Court as wrongful, the plaintiff is not allowed to recover the full claim of RM96,000.00 which was caused by vacating and relocating from both the 1st Land and the 2nd Land to another temporary site. With the lawful termination of the 1st Tenancy Agreement for the 1st Land, parts of the relocation had to be done arising from such termination. In the premises, as both the 1st Land and the 2nd Land are of equal size, the rentals for the temporary site should be allowed at half of the Plantiff's claim amount of RM96,000, ie RM48,000.

[114] Item 10 of the plaintiff's alleged loss/damages: RM263,547.00 as loss of incomes and disruption to business.