Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Kamaludin Md Said, Nordin Hassan, Ahmad Zaidi Ibrahim JJCA

[Criminal Appeal No: W-09-258-10-2020]

20 July 2022

Criminal Law: Penal Code - Section 409 - Criminal breach of trust - Appeal against setting aside of respondent's conviction and sentence - Local territorial jurisdiction - Whether High Court correct in law to overturn earlier decision of another High Court that Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had jurisdiction to try case against respondent - Whether ss 123 and 419 Criminal Procedure Code applicable - Whether Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court assigned with its local limits of jurisdiction

Criminal Procedure: Jurisdiction of court - Sessions Court - Local territorial jurisdiction - Criminal breach of trust - Appeal against setting aside of respondent's conviction and sentence - Whether High Court correct in law to overturn earlier decision of another High Court that Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had jurisdiction to try case against respondent - Whether ss 123 and 419 Criminal Procedure Code applicable - Whether Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court assigned with its local limits of jurisdiction

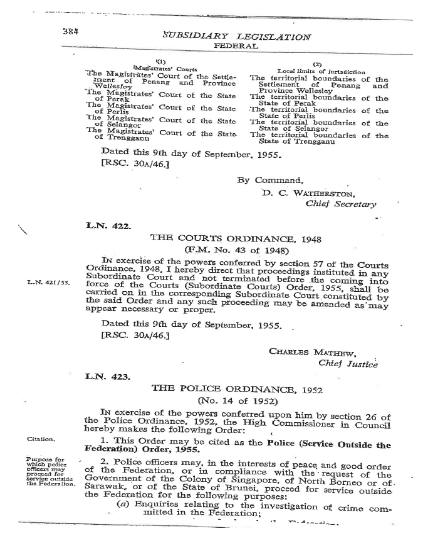

This was the Public Prosecutor's appeal against the decision of the Judicial Commissioner ("JC") of the High Court setting aside the respondent's conviction and sentence (for the offence of criminal breach of trust under s 409 of the Penal Code) by the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court on the preliminary objection raised by the respondent. The respondent's preliminary objection was that he was wrongly charged and tried in the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court instead of the Johor Bahru Sessions Court which was said to have the local limits of jurisdiction to try the case. In the course of the hearing of the respondent's appeal, the issue of local territorial jurisdiction was raised, and the JC then asked parties to submit on the effect of the Courts (Subordinate Courts) Order 1955 (L.N. 421 Tahun 1955) ("1955 Order"). The JC then decided that the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had no local territorial jurisdiction to hear the case as the offence was committed in Johor Bahru and, as such, declared the trial at the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur a nullity. The JC then quashed the conviction and sentence against the respondent without hearing the merits of the appeal. Hence, the present appeal in which the main issues for determination were: (i) whether the JC of the High Court was correct in law to overturn the earlier decision of another High Court that the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had the jurisdiction to try the case against the respondent; (ii) whether s 123 of the Criminal Procedure Code ("CPC") was applicable based on the charge and facts in this case; (iii) whether s 419 of the CPC was applicable if the case was wrongly tried in the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur; and (iv) whether Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court was assigned with its local limits of jurisdiction.

Held (allowing the appeal):

(1) There was nothing in the CPC which allowed a decision or ruling of a High Court judge to be reviewed or overruled by another High Court judge of co-ordinate jurisdiction. On the facts of the present case, Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian had decided on the issue of the jurisdiction of the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur and had given his reason for his decision. Thus, the matter should be dealt with by the Court of Appeal to determine the correctness of the said decision should there be any appeal. The revisionary power of the High Court conferred by s 323 of the CPC and ss 31 and 35(1) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 only related to revisionary jurisdiction over the subordinate courts. Nowhere did they mention the power to review the High Court's own decision. In the circumstances, the JC was wrong to overrule the decision of the earlier High Court Judge on the issue of jurisdiction. (paras 31, 39 & 44)

(2) Section 123 of the CPC, on the facts, was applicable in the present case and the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had the jurisdiction to hear the case. The offence was committed partly in Johor Bahru and partly in Kuala Lumpur, it was a continuing one and it consisted of several acts done in Johor Bahru and Kuala Lumpur. As such, s 125 of the CPC was also applicable in the present case which gave the jurisdiction to the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur to try the case. The JC, however, had failed to consider ss 123 and 125 of the CPC. He gave great emphasis on the local limits of jurisdiction and the 1955 Order but failed to address the provisions of law that conferred jurisdiction to the court. Thus, the application of the law by the JC in the present case was erroneous. (paras 52-56)

(3) The provision of s 419 of the CPC was plain and unambiguous that the finding, sentence, or order of a criminal court would not be set aside only for the reason of the wrong local area unless it caused a failure of justice. Hence, the duty of the court was to enforce this provision without giving any other interpretation. Reverting to the present case, the respondent was tried by a court of law in Kuala Lumpur. He was represented by counsel throughout the trial and had put up a complete defence. The prosecution had called 31 witnesses to establish its case whilst there were four witnesses for the defence. In the circumstances, there was no failure or miscarriage of justice against the respondent. As such, the JC was wrong in law in setting aside the conviction and sentence against the respondent on the ground of nullity for want of local limits of jurisdiction. (paras 58-60)

(4) The 1955 Order, firstly, was not an order that assigned local limits of jurisdiction to the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court, and secondly, not the order for assignment of local or territorial jurisdiction as envisaged under s 59(1) of the Subordinate Courts Act 1948 ("SCA"). In the circumstances, the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur which had not been assigned with any local limits of jurisdiction, could hear and try any case arising in any part of Peninsular Malaysia as empowered under s 59(2) of the SCA. Likewise, in the present case, the issue of local limits of the jurisdiction of the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court to try the respondent's case did not arise. Consequentially, as the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had the jurisdiction to try any case arising in any part of Peninsular Malaysia, the Practice Direction No. 2 of 2008 for Securities Commission cases in Peninsular Malaysia to be tried in the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court was in accordance with the law. This was apart from the provisions of ss 123 and 125 of the CPC or any other related provisions on the jurisdiction of the courts. (paras 70-72)

Case(s) referred to:

Azmi Osman v. Public Prosecutor and Another Appeal [2015] MLRAU 459 (refd)

Hoo Chang Chwen [1962] 1 MLRH 68 (refd)

Lim Hung Wang & Ors v. PP [2011] 1 MLRH 358 (refd)

Public Prosecutor v. Shihabduin Hj Salleh & Anor [1980] 1 MLRA 3 (refd)

Rovin Joty Kodeeswaran v. Lembaga Pencegahan Jenayah & Ors and Other Appeals [2021] 3 MLRA 260 (refd)

Tennakoon D Harold v. PP [1997] 6 MLRH 126 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Constitution (Amendment) (No 2) Act 1973, ss 3, 4

Courts Of Judicature Act 1964 ss 3, 31, 35(1)

Criminal Procedure Code ss, 121, 123, 125, 323, 419

Criminal Procedure Code [Ind], s 177

Federal Constitution, art 1(4)

Penal Code, s 409

Securities Industry Act 1983, s 87A(b)

Subordinate Courts Act 1948, ss 59(1), (2), 76(1)

Other(s) referred to:

Mallal's Criminal Procedure, 8th edn, p 254

Counsel:

For the appelant: Mohd Dusuki Mokhtar (Muhammad Azmi Mashud, Mohd Hafiz Mohd Yusof, Hashley Tajudin, Raihana Nadhira Rafidi with him); DPPs, Attorney General's Chambers

For the respondent: Muhammad Shafee (Wan Aizuddin, Nur Syahirah Hanapiah with him); M/s Shafee & Co

JUDGMENT

Nordin Hassan JCA:

[1] This is an appeal by the Public Prosecutor against the decision of the High Court dated 29 September 2020 which set aside the conviction and sentence by the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court on the preliminary objection raised by the respondent. The respondent's preliminary objection was that the respondent was wrongly charged and tried in the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court instead of the Johor Bahru Sessions Court which was said to have the local limits of jurisdiction to try the case.

The Background Facts

[2] On 13 March 2009, Toh Chun Toh Gordon ("1st accused") and Abul Hasan bin Mohamad Rashid ("2nd accused"/respondent") were charged at the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur. The principle charge against the 1st accused was for engaging in an act which operated as fraud on Multi-code Industries (M) Berhad ("Multicode") by causing the uplifting of fixed deposits belonging to Multicode amounting to RM18,146,168.74, which is an offence under s 87A(b) of the Securities Industries Act 1983 ("SIA 1983"). An alternative charge was also proffered against both the accused under s 409 of the Penal Code for criminal breach of trust, the funds of RM26,045,473.94 belonging to Multi-code.

[3] The principle charge against the respondent, translated from Bahasa Malaysia to English, reads as follows:

"That you between 26 march 207 and 28 March 2007, at Kenaga Investment Bank Berhad (Company No 15678-H) (formerly known as K&N Kenaga Berhad), Level 2, Menara Pelangi, Jalan Kuning, Taman Pelangi, 80400 Johor Bahru, in the State of Johor Darul Takzim, indirectly in connection with the purchase of securities namely 11.1 million units of Multi-code Industries (M) Berhad shares (hereinafter referred to as "the Shares"), abetted Toh Chun Toh Gordon (Singapore Passport No E0652347N) to engage in an act which operated as a fraud on Multi-code Electronics Industries (M) (Company No 193094-K) by causing the withdrawal of fixed deposit belonging to Multi-code Electronics (M) Berhad (as per appendix 1) amounting to RM18,146,168.74, out of which RM17,552,275.20 was transferred into the account of Kenanga Investment Bank Berhad (Company No 15678-H), account number 0001-312100888613 at Standard Chartered Bank Berhad, No 2, Jalan Ampang, Kuala Lumpur, for the purchase of the shares by Ace Prelude Sdn Bhd (Company No 734044) through trading account no 3AC0027 with Kenanga Investment Bank Berhad, which offence was committed as a result of your abetment and you have thereby committed an offence under s 87A(b) read together with s 122C(c) of the Securities Industries Act 1983 (Act 280) and punishable under s 122C of the same Act."

[Emphasis Added]

[4] The alternative charge against the respondent, translated to English, is as follows:

"That you between 26 march 207 and 28 March 2007, at Kenaga Investment Bank Berhad (Company No 15678-H) (formerly known as K&N Kenaga Berhad), Level 2, Menara Pelangi, Jalan Kuning, Taman Pelangi, 80400 Johor Bahru, in the State of Johor Darul Takzim, as an agent, namely a Director of Multi-code Electronics (M) Sdn Berhad and in such capacity entrusted with the dominion with a certain property (as per appendix 2) amounting to RM26,045,473.94 belonging to Multi-code Electronics Sdn Berhad and you have thereby committed criminal breach of trust of the said amount and as such you have committed an offence punishable under s 409 Of the Penal Code (Act 574)"

[Emphasis Added]

[5] On 27 September 2010, the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court decided that the prosecution had proved a prima facie case against both the accused on the charges proffered against them and called them to enter their defence. Having heard their defence and assessed the totality of the evidence, the Sessions Court judge decided that both the accused had failed to raise a reasonable doubt in the prosecution case and convicted them for the alternative charge. The 1st accused was then sentenced to 12 years imprisonment and a fine of RM1 million, whilst the 2nd accused, the respondent in the present appeal, was sentenced to 6 years imprisonment.

[6] Aggrieved by the decision, both the accused appealed against the said decision to the High Court.

[7] However, the appeal by the 1st accused was abated when he passed away on 27 August 2012.

[8] At the High Court, before justice Dato Indera Mohd Suffian bin Tan Sri Abd. Razak, counsel for the respondent raised a preliminary issue that the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had no jurisdiction to hear the case as the offence occurred in Johor Bahru. The preliminary issue was heard on 11 December 2018, 22 February 2019, and 6 March 2019, and on 14 June 2019 the High Court judge dismissed the preliminary issue on jurisdiction and ordered parties to proceed with the merits of the appeal. The reason to dismiss the preliminary issue inter alia on the ground that the principle charge and the alternative charge were interconnected and the application of s 123 of the Criminal Procedure Code ("the CPC").

[9] The appeal to hear its merit was then transferred to another High Court before Judicial Commissioner Datuk Aslam bin Zainuddin (as he then was). Counsel for the respondent then informed the court that they wish to submit again on the preliminary issue on jurisdiction which was objected to by the Deputy Public Prosecutor as the matter had been decided earlier. In any event, the judge instructed parties to file a written submission addressing the issue of whether the preliminary issue which had been decided by the High Court earlier, can be relitigated again before another High Court.

[10] On 7 February 2020, the Judicial Commissioner decided that the preliminary issue could not be relitigated again and fixed another date to hear the merits of the appeal.

[11] On the hearing date, in the course of the hearing of the appeal on merits, the issue of local territorial jurisdiction was again raised, and the Judicial Commissioner then asked parties to submit the effect of the Courts (Subordinate Courts) Order 1955 (L N 421 Tahun 1955) ("the 1955 Order"). The submission on this issue was heard by the Judicial Commissioner on 5 August 2020.

[12] On 29 September 2020, the Judicial Commissioner decided that the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had no local territorial jurisdiction to hear the case as the offence was committed in Johor Bahru and as such declared the trial at the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur a nullity. The Judicial Commissioner then quashed the conviction and sentence against the respondent without hearing the merits of the appeal.

[13] Hence, the present appeal by the Public Prosecutor.

The Main And Relevant Issues For Consideration Of This Court

[14] Having read the records of appeal and written submission and after hearing the oral submission by parties, the main issues for our determination before coming to our decision are as follows:

(i) whether the Judicial Commissioner of the High Court was correct in law to overturn the earlier decision of another High Court who had decided that the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had the jurisdiction to try the case against the respondent;

(ii) whether s 123 of the CPC is applicable based on the charge and facts in this case;

(iii) whether s 419 of the CPC is applicable if the case was wrongly tried in the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur;

(iv) whether Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court was assigned with its local limits of jurisdiction.

[15] The other related issue shall be dealt with in determining the main issues mentioned above.

[16] Before we proceed to deal with the issues in the present appeal, it is helpful to lay down the established facts during the trial at the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court. The finding of facts by the trial judge essentially, are as follows.

The Prosecution's Case

[17] Multi-code Electronics Sdn Berhad ("Multi-code") is a public listed company since 1997. Goh Tong Huat (PW1) has been the Managing Director of Multi-code and PW1 and his wife owned 28.4% shareholding in the company.

[18] Sometimes at the end of February or early March 2007, a meeting was held at the Zon Hotel in Johor Bahru. Present in the meeting were PW1, Nora Lam (PW2), Goh Kar Choon (PW6), Gordon Toh Chun Toh (1st accused), Wee Chee Leong, and one Danial Wong. In the meeting, the 1st accused informed PW1 that he was a fund manager, had funds in Malaysia and was interested to buy PW1's shares in Multi-code. PW1 was also informed by the 1st accused that he will use Ace Prelude Sdn Bhd ("APSB") to buy the shares as he was also the representative of APSB.

[19] On 22 March 2007, PW1 sold his and his family members' shareholdings in Multi-code amounting to 11.1 million shares to the 1st accused through APSB.

[20] Soon after the said shares transaction, the Multi-code's Board of Director meeting was convened wherein PW1 resigned as director of Multi-code and the 1st accused was appointed as a director and Chief Executive Officer of Multi-code. In the same meeting, the respondent was also appointed as a director of Multi-code. Both the 1st accused and the respondent were also made the authorized signatories of Multi-code accounts which include its fixed deposits account.

[21] In this Board of Directors' meeting, no approval was sought to uplift the fixed deposits nor any discussion was held on the uplifting of the fixed deposits.

[22] On 26 March 2007, PW1 handed over the Multi-code fixed deposit certificates to the 1st accused in the presence of the respondent, PW6 and Ang Ai Ling (PW4). Immediately after the handover of the certificates, the 1st accused together with the respondent and Tee Keng See (PW5) went to Public Bank, RHB Bank, Maybank, Bank Rakyat, and Affin Bank where the fixed deposits were uplifted and transferred to third party accounts.

[23] The fixed deposits in Public Bank, RHB Bank, and Bank Rakyat were uplifted and transferred to Elliot Gordon Singapore Pte Ltd ("EGS") account which was maintained at Ambank, Kuala Lumpur in the amount of RM18,146,168.74. The 1st accused was the sole authorised signatories of the EGS's account.

[24] Respondent as one of the authorised signatories of the Multi-code's account had signed 66 bank documents for the uplifting and transferring of the fixed deposits to the third parties' accounts.

[25] On 27 March 2007, upon the instruction of the 1st accused, a sum of RM17,552,275.20 was transferred from the EGS's account to Kenanga Investment Bank Berhad's account at Standard Chartered, Kuala Lumpur. The transfer was made to settle the payment for the purchase of the 11.1 million shares sold by PW1 and his family members.

[26] Thereafter, on 28 March 2007, the said sum of RM17,552,275.20 was paid to PW1 and his family members for the sale of the 11.1 million Multicode shares.

The Decision Of The Trial Judge At The End Of The Prosecution Case

[27] Having analysed the evidence presented through all the prosecution's witnesses and having considered the relevant laws, at the end of the prosecution case, the trial judge found that the prosecution had proved its case against both the 1st accused and the respondent on the principle and alternative charges proffered against them. Hence, both of them were called to enter their defence.

The Defence

[28] Essentially, the respondent's defence can be summed up as follows. That the Board of Directors of Multi-code had approved the uplifting of the fixed deposits in the meeting on 23 March 2007, all the bank documents for the uplifting of the fixed deposits were pre-signed upon the request of one Danial Wong, and the fixed deposits were uplifted to check whether there exist any negative pledge and the respondent did not benefit from the whole transaction.

The Decision Of The Trial Judge At The End Of The Case

[29] At the end of the defence case and having considered the totality of the evidence, the trial judge found that the defence had failed to raise any reasonable doubt in the prosecution case and was satisfied that the prosecution had succeeded in proving the alternative charge for criminal breach of trust under s 409 of the Penal Code beyond a reasonable doubt against the 1st accused as well as the respondent. Therefore, they were convicted and sentenced accordingly on the said charge.

The Issues Before This Court

Whether The Judicial Commissioner Of The High Court Was Correct In Law To Overturn The Earlier Decision Of Another High Court Who Had Decided That The Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court Had The Jurisdiction To Try The Case Against The Respondent?

[30] Counsel for the respondent submitted that the judicial Commissioner was correct to review the decision of the earlier High Court Judge on the issue of jurisdiction, based on the following grounds:

(i) The earlier High Court Judge was not referred to the 1955 Order which provides the local limits of the jurisdiction of the Sessions Court and therefore, this discovery of new fact was not known to the earlier High Court Judge at the time the earlier decision was made. The decision of the High Court in the case of Lim Hung Wang & Ors v. PP [2011] 1 MLRH 358 was cited to support the contention.

(ii) The earlier High Court judge failed to take into consideration the 1948 Order on the issue of local jurisdiction and as such the decision was erroneous which resulted in injustice. This 1948 Order was replaced or substituted by the 1955 Order.

[31] To begin with, there is nothing in the CPC which allows a decision or ruling of a High Court judge to be reviewed or overruled by another High Court judge of co-ordinate jurisdiction. In the present case, Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian had decided on the issue of the jurisdiction of the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur and had given his reason for his decision. Thus, the matter should be dealt with by the Court of Appeal to determine the correctness of the said decision should there be any appeal. The decision of the Judicial Commissioner to overrule the decision of Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian, we find, is erroneous.

[32] This court had dealt with a similar issue in the case of Azmi Osman v. Public Prosecutor and Another Appeal [2015] MLRAU 459 where Abang Iskandar JCA (as he then was, now CJSS) addressed the issue in the following manner:

"[27] It was apparent to us from a reading of his grounds of decision that the HCJ2 had reasoned out that as his jurisdiction vis-a-vis the earlier HCJ1 was of coordinate jurisdiction, he was therefore not bound by the earlier decision of the HCJ1 in calling for the defence to be entered and that he could therefore review the HCJ1's decision and determine for himself as to whether on the evidence as led by the prosecution had established a prima facie case and whether defence ought to be called. On that understanding, the HCJ2 had reviewed the evidence and concluded that the HCJ1 was wrong in calling for the accused to enter his defence on all the four charges. His reason was because the evidence led by the prosecution did not establish a prima facie case on all the four charges for money-laundering offences.

[28] With respect, we are of the view that the learned HCJ2 had erred when he disturbed the findings of the earlier HCJ1 who had ordered the accused to enter on his defence to all the four charges, on appeal. The dominant issue that ought to guide the HCJ2's mind in dealing with a situation that has now become this preliminary issue must of necessity be the fact that when the HCJ1 made that decision for defence to be called, the latter was carrying out his appellate jurisdiction. Granted that the High Court' jurisdiction is coordinated among its judges, inherent in that concept is the fact that a High Court judge cannot overrule another High Court judge who had made a decision at some crucial stage of proceedings in the same case. In the context of this appeal before us, the HCJ1 had ordered the accused's defence to be called to answer to the four charges leveled against him. The jurisdiction to correct that purported error, said by the HCJ2 as having been committed by the HCJ1, with respect, lies with the Court of Appeal, should there be an appeal against the decision of the HCJ2. In other words, as much as a High Court judge's decision does not bind his brother or sister judge on the High Court bench, by the same token, neither does it lie with his brother or sister judge of the High Court to overturn his decision in the same case. In a situation now prevailing in this case, the role of the HCJ2 is only limited to see whether the defence evidence as led has succeeded in creating a reasonable doubt in the prima facie case as found by the HCJ1 on appeal by the prosecution. With respect, this must be preferred position as to what the proper approach ought to be, as was employed by the Court of Appeal in the Sulaiman case. Coordinate jurisdiction connotes parity and as such, it does not admit nor permit mutual over-riding or over-ruling each other's decision. Only a higher appeal court can disturb or vary or affirm a High Court decision.

[29] In the context of the situation that arose in this case before us, it is therefore our view that the reason advanced by the learned HCJ2 that had purportedly provided him with the power to review the HCJ1 decision to call for the defence to be entered was, with respect, flawed and erroneous. As such, on the preliminary issue raised by the learned deputy, we find that there is merit in his contention. The learned HCJ2 was wrong in reviewing and overturning the earlier decision of the HCJ1, in the first appeal by the prosecution. His role, in the circumstances, as stated above, is limited to determining whether the defence had raised a reasonable doubt at the end of the defence case."

[Emphasis Added]

[33] In this regard, counsel for the respondent argued that the decision on the issue of jurisdiction by justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian is unappealable as it was not a decision as defined under s 3 of the Court of Judicature Act 1964 as the rights of parties have yet to be disposed of. Here, we find the argument is misplaced as the right to appeal to the Court of Appeal is still available after the completion of the appeal on merits and the issue of jurisdiction can be made as one of the grounds of appeal.

(See Tennakoon D Harold v. PP [1997] 6 MLRH 126 PP v. Hoo Chang Chwen [1962] 1 MLRH 68)

[34] In the present case, not only did the Judicial Commissioner overrule the decision of Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian, but also reviewed his own decision that was made on 7 February 2020 which ruled that the decision by Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian cannot be relitigated again and instructed parties to proceed with the merits of the appeal. Having perused the grounds of judgment of the Judicial Commissioner, no statutory provision was cited that empower the Judicial Commissioner to overrule the decision of Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian but on the sole ground that the 1955 Order was not brought to the attention of Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian.

[35] In the grounds of judgment, the Judicial Commissioner said this:

"Based on the above two cases of Lim Hung Wang & Ors v. PP [2011] 1 MLRH 358 and PP v. Ng Lai Huat & Others [1990] 2 MLRH 80, I can revisit the issue. More so when the 1955 order was not brought to the attention of my learned brother judge. I cannot ignore the existence of the 1955 Order, which is still in force, in coming to my decision."

[36] The two cases referred by the Judicial Commissioner inter alia involve the decision of the High Court to review its own decision. In Lim Hung Wang's case (supra), the application to review the earlier decision of the High Court in its findings on the prima facie case was dismissed. The judge endorsed the view that the power to review must be given by statute. Zawawi Salleh J (as he then was) said this:

"[32] In KTS News Sdn Bhd v. See Hua Realty Bhd & Anor [2011] 1 MLRA 50, Low Hop Bing JCA upon deliberation on the meaning of "review" had this to say:

[26] In our view, the conferment of "review jurisdiction" is not by way of inherent powers. Such review jurisdiction must be expressly provided by statute. Authorities abound in support of this proposition. Illustrations are found in:

(a) Harbhajan Singh v. Karam Singh AIR (53) [1966] SC 641: At p 642 Ramaswami J held that the court's power to review must be given by statute.

(b) Drew v. Willis [1981] 1 QB 450: Lord Esher, MR pointed out that no court has a power of setting aside an order which has been properly made, unless it is given by statute.

(c) Anantharaju Shetty v. Appu Hegade, AIR [1919] Mad 244. Seshagiri Aiyar, J of the Madras High Court opined:

It is settled law that a case is not open to appeal unless the statute gives such a right. The power to review must also be given by statute. Prima facie a party who has obtained a decision is entitled to keep it unassailed, unless the Legislature had indicated the mode by which it can be set aside. A review is practically the hearing of an appeal by the same officer who decided the case. There is at least good reason for saying that such power should not be exercised unless the statute gives it,...

(d) Trilok Singh v. State Transport Authority, Bihar AIR [1985] Patna 87: At p 88, Ashwini Kumar Sinha J said that it is well settled that the power of review is not an inherent power but is created by statute and expressly conferred by the statute. The power of review has always been held to be a creature of statute.

(e) Fernandes v. Ranganayakulu AIR [1953] Mad 236: At p 237 Ramaswami J echoed the same sentiment when he said that so far as the invocation of the inherent powers of court is concerned, it has been held repeatedly and has now become well settled law that the power to review is not an inherent power, but such a right must be conferred by statute.

[33] One cannot help but notice that the above said authorities dealt with the finality of decision or judgment. However, regard shall be made that if the application of review jurisdiction is strictly exercised in the case of final judgment and/or decision, what more in any finding or ruling by this court to call the applicants to enter upon their defence at the end of the prosecution case?

[34] In spite of best efforts by learned counsel, this court is unable to persuade itself to hold that the court has the power to review its own finding or decision on prima facie case at the end of the prosecution case."

[Emphasis Added]

[37] Reverting to the present case, the statute that cloth the High Court with the power to review is provided under s 323(1) of the CPC which provides:

"323. (1) A Judge may call for and examine the record of any proceeding before any subordinate Criminal Court for the purpose of satisfying himself as to the correctness, legality, or propriety of any finding, sentence, or order recorded or passed, and as to the regularity of any proceedings of that subordinate Court."

[Emphasis Added]

[38] Further, the High Court is also provided the power of revision under ss 31 and 35(1) of the Court of Judicature Act 1964 ("the CJA") which states:

"Section 31-

The High Court may exercise powers of revision in respect of criminal proceedings and matters in subordinate courts in accordance with any law for the time being in force relating to criminal procedure.

Section 35(1)-

In addition to the powers conferred on the High Court by this or any other written law, the High Court shall have general supervisory and revisionary jurisdiction over all subordinate courts, and may in particular, but without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing provision, if it appears desirable in the interests of justice, either of its own motion or at the instance of any party or person interested, at any stage in any matter or proceeding, whether civil or criminal, in any subordinate court, call for the record thereof, and may remove the same into the High Court or may give to the subordinate court such directions as to the further conduct of the same as justice may require"

[39] The above-mentioned statutes clearly provide that the revisionary power of the High Court conferred by ss 323 of the CPC and ss 31 and 35(1) of the CJA only relates to revisionary jurisdiction over the subordinate courts. Nowhere does it mention the power to review the High Court's own decision.

[40] In fact, in Lim Hung Wang's case (supra) it was held that the court had no power to review its findings on a prima facie case. Further, the judge in that case was of the view that to use inherent power to allow the High Court to review its own decision would cause chaos to the administration of the criminal system and open the door to a number of applications in the course of criminal trials which could frustrate criminal proceedings and bring proceedings at all levels of our criminal court to halt.

[41] Likewise in the present case, the effect of allowing the Judicial Commissioner to overrule another High Court Judge's decision on the issue of jurisdiction and reviewed its own decision to relitigate the said issue having decided earlier that the Judicial Commissioner had not been empowered to do so, would also create chaos to the administration of criminal system as envisaged by the learned Judge in Lim Hung Wang's case.

[42] Further, in Lim Hung Wang's case, we noted that the judge did say that if the High Court has the power to review its own decision, it must be exercised in exceptional circumstances and cannot be used to allow parties to remedy their failing and oversights during trial or backdoor method to relitigate their case. At paras [43] and [44] of the judgment, this was said:

"[43] Further, learned counsel did not indicate where the court could have erred in making such finding. The burden rests upon the applicants to demonstrate the exceptional circumstances which warrant this court to review its own finding. To my mind, exceptional circumstances include:

(a) discovery of a new fact not known by the court at the time it made the original decision;

(b) emergence of new evidence which could have a decisive factor in reaching the original decision;

(c) a material change in circumstances since the original decision; and

(d) a reason to believe that the original decision was erroneous or constituted an abuse of power that resulted in an injustice.

[44] The court's power to review, if any, is not designed for the purpose of allowing parties to remedy their own failing or oversights during trial or to provide a backdoor method by which the parties can seek to reargue or relitigate their cases."

[Emphasis Added]

[43] As discussed earlier, the High Court has no power to review its own decision but be that as it may, having considered the facts in the present case, it is our view that the emergence of the 1955 Order brought by the Judicial Commissioner is not a decisive factor in the original decision by Justice Dato' Indera Mohd Suffian which ruled that the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had the jurisdiction to hear the case. We will elaborate further on this issue.

[44] In the circumstances, we are of the view that the Judicial Commissioner was wrong to overrule the decision of the earlier High Court Judge on the issue of jurisdiction and further to review its own decision which was made on 7 February 2020.

[45] On this ground alone, the appeal by the Public Prosecutor can be determined but for the sake of completeness, we will deal with the remaining issues.

Whether Section 123 Of The CPC Is Applicable Based On The Charge And Facts In This Case?

[46] In deciding whether a court has jurisdiction to hear and try a criminal case, all relevant federal laws need to be looked into and one of which is s 123 of the CPC. As emphasized by the Federal Court in Rovin Joty Kodeeswaran v. Lembaga Pencegahan Jenayah & Ors and Other Appeals [2021] 3 MLRA 260:

"[121] The court's function as a court of law is to decide cases that came before it in accordance with the Federal Law which is enforced at the material time."

[Emphasis Added]

[47] Section 123 of the CPC provides:

"When an act is an offence because of its relation to any other act which is also an offence or which would be an offence if the person was capable of committing an offence a charge of the first-mentioned offence may be inquired into or tried by a Court within the local limits of whose jurisdiction either act was done."

[Emphasis Added]

[48] The provision of s 123 of the CPC allows a case to be tried at a place the act committed is an offence because of its relationship with another act which is also an offence. This provision can be considered an exception to the local limits of jurisdiction provided under s 121 of the CPC which states:

"Every offence shall ordinarily be inquired into and tried by a Court within the local limits of whose jurisdiction it was committed."

[49] Further illustration (a) of s 123 states:

"(a) A charge of abetment may be inquired into or tried either by the Court within the local limits of whose jurisdiction the abetment was committed or by the Court within the local limits of whose jurisdiction the offence abetted was committed."

[Emphasis Added]

[50] In the present case, the principle charge and the alternative charge as alluded to earlier are inter-related. The fraudulent transaction involves the purchase of the 11.1 million shares of Multi-code. The charge as well as the evidence presented by the prosecution shows that the amount of RM17,552,275.20 from the uplifting of Multi-code fixed deposits was transferred and paid into Kenanga Investment Bank Berhad at Standard Chartered Bank Berhad in Kuala Lumpur. This amount was then paid to PW1 and his family members for the purchase of the shares. Here, the purchase of the shares was completed when payment was made and this happened in Kuala Lumpur as the monies for the payment had been deposited in Standard Charted Bank in Kuala Lumpur. It is to be noted that the principle charge against the respondent, in this case, was for the offence of abetting the 1st accused in the fraudulent transaction. The offence abetted was completed when the payment of the Multi-code shares was fully made and that was in Kuala Lumpur.

[51] In addition, the word 'ordinarily' in the phrase "be inquired into and be tried" under s 121 of the CPC which is pari materia with s 177 of the Indian Criminal Procedure Code has been explained in Mallal's Criminal Procedure 8th edn at p 254 as follows:

"Shall ordinarily be tried"

[688] The term 'ordinarily' has been judicially defined to mean 'except in cases provided hereinafter to the contrary. Thus, a Magistrate may try an offence not falling within the territorial jurisdiction of his court, if there are specific provisions allowing him to do so..

[Emphasis Added]

[52] In the present case, s 123 of the CPC allows or confers the jurisdiction to the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur on the facts alluded to earlier.

[53] As such, we are of the view that s 123 of the CPC is applicable in the present case and the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court had the jurisdiction to hear the case.

[54] Apart from s 123 of the CPC, we also find that s 125 of the same Code is also relevant in the determination of the issue of jurisdiction. Section 125 states:

"If-

(a) when it is uncertain in which of several local areas an offence was committed;

(b) where an offence is committed partly in one local area and partly in another;

(c) where an offence is a continuing one and continues to be committed in more local areas than one; or

(d) where it consists of several acts done in different local areas,

it may be inquired into or tried by a Court having jurisdiction over any of such local areas.

[55] Based on the facts alluded to earlier, the offence is committed partly in Johor Bahru and partly in Kuala Lumpur, it was a continuing one and it consists of several acts done in Johor Bahru and Kuala Lumpur. As such, s 125 of the CPC is also applicable in the present case which gave the jurisdiction to the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur to try the case.

[56] However, in the present case, the Judicial Commissioner had failed to consider ss 123 and 125 of the CPC which confers the jurisdiction to the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court based on the facts presented. The Judicial Commissioner gave great emphasis on the local limit of jurisdiction and the 1955 Order but failed to address the provisions of law that confers the jurisdiction to the court as discussed earlier. The application of the law by the Judicial Commissioner in the present case was erroneous.

Whether Section 419 Of The CPC Is Applicable If The Case Was Wrongly Tried In The Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur?

[57] The next pertinent issue is the application of s 419 of the CPC which provides:

"No finding, sentence or order of any criminal Court shall be set aside merely on the ground that the inquiry, trial or other proceedings in the course of which it was arrived at, passed or made, took place in a wrong local area or before a wrong Magistrate or Court, unless it appears that such error occasioned a failure of justice."

[Emphasis Added]

[58] The provision of s 419 is plain and unambiguous that the finding, sentence, or order of a criminal court shall not be set aside only for the reason of the wrong local area unless it causes a failure of justice. Hence, the duty of the court is to enforce this provision without giving any other interpretation.

[59] The Supreme Court in Public Prosecutor v. Shihabduin Hj Salleh & Anor [1980] 1 MLRA 3 explained the need to enforce the plain and clear wordings of a statute in the following manner:

"Thirdly, if the law-maker so amends the law, to paraphrase the words of Lord Diplock at p 541 in Duport Steels Ltd v. Sirs [1980] 1 All ER 529, the role of the judiciary is confined to ascertaining from the words that the law-maker has approved as expressing its intention what that intention was, and to giving effect to it. Where the meaning of the words is plain and unambiguous it is not for Judges to invent fancied ambiguities as an excuse for failing to give effect to its plain meaning because they themselves consider that the consequences of doing so would be inexpedient, or even unjust or immoral or to paraphrase the words of Lord Scarman at p 551 in the same case, in the field of statute law the Judge must be obedient to the will of the lawmaker as expressed in its enactments, the Judge has power of choice where differing constructions are possible, but he must choose the construction which in his judgment best meets the legislative purpose of the enactment. Even if the result is unjust but inevitable, he must not deny the statute; unpalatable statute law may not be disregarded or rejected, simply because it is unpalatable; the Judge's duty is to interpret and apply it."

[Emphasis Added]

[60] Reverting to the present case, the respondent was tried by a court of law in Kuala Lumpur. He was represented by counsel throughout the trial and having perused the notes of proceedings, we find that the respondent had put up a complete defence. The prosecution had called 31 witnesses to establish its case whilst there were 4 witnesses for the defence which includes both the accused. In the circumstances, we find there is no failure or miscarriage of justice against the respondent. As such, the Judicial Commissioner was wrong in law in setting aside the conviction and sentence against the respondent on the ground of nullity for want of local limits of jurisdiction.

Whether Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court Was Assigned With Its Local Limits Of Jurisdiction?

[61] We find, that this is an important issue for determination and our findings will have consequences on the application of Practice Direction No 2 of 2008 (PD 2/2008) issued by the Chief Justice of Malaya with effect from 5 September 2008. The directive under PD 2/2008 inter alia is that all Security Commission cases be heard and tried at the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court.

[62] One of the provisions of law to look at in determining this issue is s 59 of the Subordinate Courts Act 1948 ("the SCA 1948") which provides:

"Constitution and territorial jurisdiction of Sessions Courts

59. (1) The Yang di-Pertuan Agong may, by order, constitute so many Sessions Courts as he may think fit and shall have power, if he thinks fit, to assign local limits of jurisdiction thereto.

(2) Subject to this Act or any other written law, a Sessions Court shall have jurisdiction to hear and determine any civil or criminal cause or matter arising within the local limits of jurisdiction assigned to it under this section, or, if no such local limits have been assigned, arising in any part of Peninsular Malaysia.

(3) Each Sessions Court shall be presided over by a Sessions Court Judge appointed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong on the recommendation of the Chief Judge.

(4) Sessions Courts shall ordinarily be held at such places as the Chief Judge may direct, but should necessity arise they may also be held at any other place within the limits of their jurisdiction."

[63] Section 59(1) of the SCA 1948 provides that the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong ("YDPA") by order, may constitute Sessions Courts and assign its local limits of jurisdiction if the YDPA thinks fit. However, if no local limits of jurisdiction have been assigned, the Sessions Court may hear and determine any case arising in any part of Peninsular Malaysia as stated under s 59(2) of the same Act.

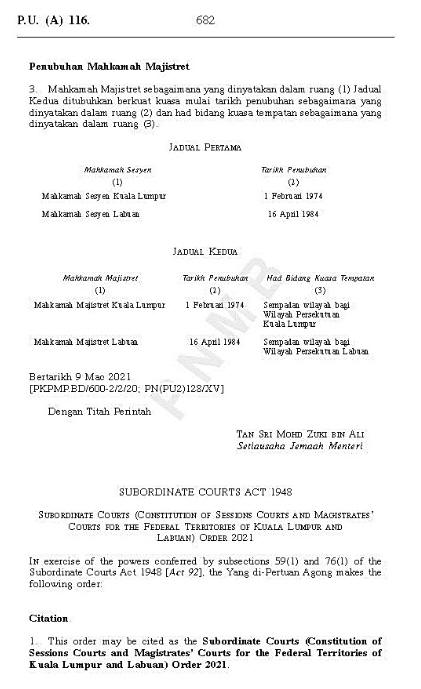

[64] The next piece of document which is pertinent to this issue is the Gazette dated 17 March 2021. For ease of reference the gazette is reproduced below:

[65] By this Gazette dated 17 March 2021, the YDPA makes the order for the constitution of the Kuala Lumpur and Labuan Sessions Courts under s 59(1) of the SCA 1948 and the constitution of the Kuala Lumpur and Labuan Magistrate Courts under s 76(1) of the same act. In addition, the YDPA also makes the order assigning the territorial jurisdiction of the Magistrate Courts Kuala Lumpur and Labuan. However, no assignment was made as regards the territorial jurisdiction of the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur and Labuan.

[66] In the circumstances, we are of the considered view that since there is no assignment of local or territorial limits of jurisdiction to the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court, s 59(2) of the SCA 1948 comes into play, the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court may hear and determine any case arising in any part of Peninsular Malaysia.

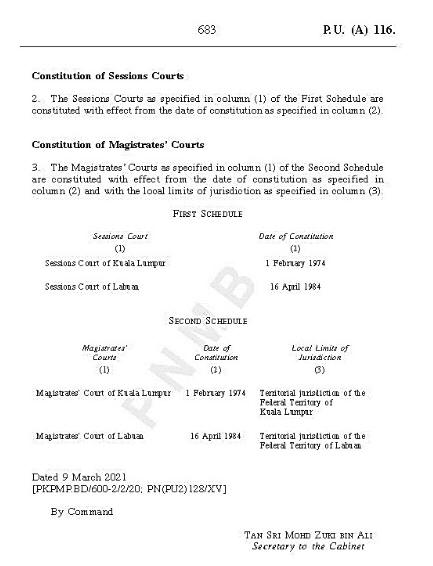

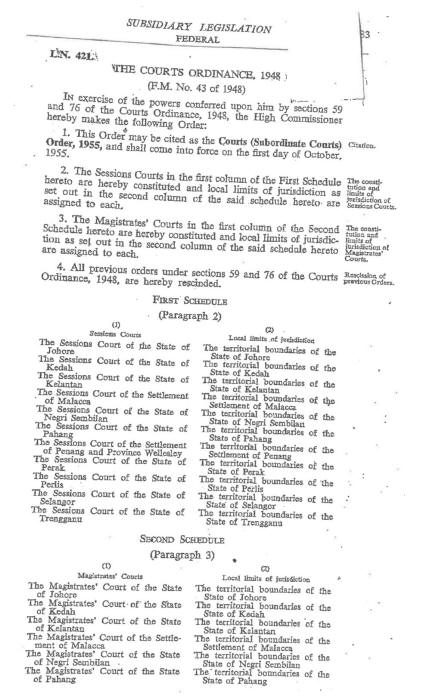

[67] The reasoning of the Judicial Commissioner in the present case, that the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court was assigned with its local limits of jurisdiction under the 1955 Order, we find was flawed. The 1955 Order only assigned the local limits of jurisdiction to the Sessions Court of the State of Selangor. Undoubtedly, this is because the Federal Territory Kuala Lumpur and Labuan were then not in existence. For ease of reference, we reproduced the 1955 Order below:

[68] The Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur was established on 1 February 1974 by the Constitution (Amendment) (No 2 Act 1973 (Act A206). Section 3 of the Act provides the exclusion of the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur from the State of Selangor and s 4 of the same Act confers the jurisdiction over the Federal Territory to the Federation.

Section 3 states:

The Federal Territory shall cease to form part of the State of Selangor and the Ruler of the State of Selangor shall relinquish and cease to exercise any sovereignty over the Federal territory and all power and jurisdiction of the Ruler and the Legislative Assembly of the State of Selangor in or in respect of the Federal territory shall come to an end.

Section 4 provides:

The Federation shall exercise sovereignty over the Federal territory and all power and jurisdiction in or in respect of the Federal territory shall be vested in the Federation.

[Emphasis Added]

[69] The establishment of the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur is also stipulated under art 1(4) of the Federal Constitution which states:

"(4) The territory of the State of Selangor shall exclude the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur established under the Constitution (Amendment) (No 2 Act 1973 [Act A206] and the Federal Territory of Putrajaya established under the Constitution (Amendment) Act 2001 [Act A1095] and the territory of the State of Sabah shall exclude the Federal Territory of Labuan established under the Constitution (Amendment) (No 2) Act 1984 [Act A585], and all such Federal Territories shall be territories of the Federation."

[Emphasis Added]

[70] Hence, the 1955 Order which was made by the High Commissioner, firstly, is not an order that assigned local limits of jurisdiction to the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court, and secondly, not the order for assignment of local or territorial jurisdiction by the YDPA as envisaged under s 59(1) of the SCA 1948.

[71] In the circumstances, the Sessions Court Kuala Lumpur which has not been assigned with any local limits of jurisdiction, may hear and try any case arising in any part of Peninsular Malaysia as empowered under s 59(2) of the SCA 1948. Likewise, in the present case, the issue of local limits of the jurisdiction of the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court to try the respondent's case does not arise.

[72] Consequentially, as the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court has the jurisdiction to try any case arising in any part of Peninsular Malaysia, the PD 2/2008 for Securities Commission cases in Peninsular Malaysia to be tried in the Kuala Lumpur Sessions Court is in accordance with the law. This is apart from the provisions of ss 123 and 125 of the CPC discussed earlier or any other related provisions on the jurisdiction of the courts.

Conclusion

[73] Based on the aforesaid reasons, it is our unanimous decision that the appeal by the Public Prosecutor is allowed, and the decision of the Judicial Commissioner is set aside. The case is sent back to the High Court to hear the appeal on its merits by another High Court Judge.