Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Lee Swee Seng, Hadhariah Syed Ismail, Supang Lian JJCA

[Civil Appeal Nos: W-02(NCC)(W)-1528-08-2021 & W-02(NCC)(W)-1595-08- 2021]

9 June 2022

Civil Procedure: Appeal - Stay of execution of judgment - Appeal to the Court of Appeal - Stay of execution of High Court judgment sought from Court of Appeal - Whether application for stay ought to be made to High Court first - Power of Court of Appeal to preserve status quo and prevent prejudice to parties pending appeal - Courts of Judicature Act 1964, s 43

Civil Procedure: Appeal - Stay of execution of judgment - Stay of execution of High Court judgment pending appeal to Court of Appeal - Whether unsuccessful party ought to first exhaust all avenues of appeal before successful party entitled to execute judgment - Whether successful party in litigation entitled to fruits of his litigation - Whether Court ought to maintain a dynamic balance of parties' competing concerns in determining application for stay of judgment - Whether Court could explore partial conditional stay upon terms

Civil Procedure: Stay of execution of judgment - Application for - Special circumstances - Whether impecuniosity of successful litigant alone a "special circumstance" justifying unconditional stay of whole judgment debt - Successful corporate litigant in tight financial straits and running at a loss - Successful corporate litigant's assets valued at less than half of its total liabilities - Possibility of successful litigant's directors withdrawing whole judgment sum to pay creditors, themselves or make risky investments - Relative ease at which money might be withdrawn from successful corporate litigant's banking account - Whether such circumstances justified partial stay on terms

Civil Procedure: Stay of execution of judgment - Application for - "Special circumstances", how established - Whether merits or lack thereof of judgment sought to be stayed irrelevant at stay stage - Whether possibilities of failure or success of appeal against judgment sought to be stayed irrelevant at stay stage

Civil Procedure: Stay of execution of judgment - Application for - Stay of judgment pending appeal - Discretion of court, how exercised - Whether dependent on "special circumstances" - Whether appeal could stay execution of judgment - Rules of Court, O 47 r 1

The parties herein were involved in a business joint-venture that failed and resulted in inter-related civil suits among themselves. In OS 47, the appellants had sued the respondents in the High Court alleging oppression in a company - GTG - in which both the 1st appellant and 1st respondent held 50% of the shares. The High Court allowed OS 47, ordered the winding-up of GTG and further ordered the appellants to pay a sum of RM22,666,195.16 to the 1st respondent with costs of RM500,000. The appellants' application for stay was dismissed by the High Court and the appellants thus filed NU4 in the Court of Appeal seeking a stay of execution or enforcement pending their appeal to the Court of Appeal. The appellants also filed NU5 in the Court of Appeal for a stay of execution in respect of an order of costs of RM100,000 ordered against the appellants, arising out of the dismissal of a series of consolidated civil suits that the appellants had commenced against the respondents. The High Court had dismissed an earlier application for stay in the consolidated civil suits. The Court of Appeal had thus to determine both the stay applications - NU4 and NU5.

Held (allowing NU4 conditionally but dismissing NU5 with costs):

(1) The Court, pursuant to O 47 r 1(1) of the Rules of Court, had discretion to grant or not to grant a stay of execution of a judgment pending appeal depending on whether there were "special circumstances". Such special circumstances must be deposed to in the affidavits supporting the application and refuting the objection to the stay. The Court also had discretion to impose a conditional stay subject to terms of the whole or part of the judgment sum ordered. "Special circumstances" existed where if an appeal were to succeed, the appeal would nevertheless be rendered nugatory if the successful appellant were to be deprived of the results of his successful appeal. (paras 17 & 33)

(2) An appeal did not operate as a stay of execution of the payment of the judgment sum, unless the High Court that granted the judgment or the Court appealed to (Court of Appeal) so orders. Under s 43 of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 ("CJA") any stay application had to be made to the High Court first. In the instant case, such applications had been made and dismissed by the High Court. The power of the Court of Appeal generally to preserve status quo and prevent prejudice to the claims of parties pending the hearing of an appeal was also found in s 44 of the CJA. (paras 18-19)

(3) In finding whether or not "special circumstances" existed, the Court should have regard to all relevant factors. It shoud not take into consideration irrelevant factors, bearing in mind the basic general principles and the exceptions to it. Where a stay of execution of a judgment of the Court below was sought, the merits or the lack of merits was not a relevant consideration at the stay. Whether an appeal was doomed to fail or was bound to succeed was of no relevance since such matters were only to be considered in the appeal proper and not during the stay of execution of the judgment. (paras 21-22)

(4) Generally, a successful litigant was not to be deprived of the fruits of his litigation. The law did not require the unsuccessful litigant to first exhaust all avenues of appeal before the successful litigant might recover the judgment debt through execution. The Court in hearing a stay application had to balance the competing rights, interests, needs and concerns of the parties. The Court had to also maintain a dynamic balance of the competing concerns so that no one ought to be deprived of his fruits of litigation, be it having succeeded at the trial court or having lost at the trial court but succeeding on appeal. Courts had increasingly been inclined to explore a partial conditional stay upon terms to balance the competing rights, interest, needs and concerns of the parties without offending the general principle that a party successful in litigation even at first instance was entitled to the fruits of his litigation unless "special circumstances" could be shown by the unsuccessful party that was appealing. (paras 24, 28, 29 & 39)

(5) Generally, the impecuniosity or precarious financial position of the successful litigant was not by itself a "special circumstance" justifying an unconditional stay of the whole of the judgment debt. In the instant case, a huge sum of money was due to the 1st respondent Company which was in tight financial straits and running at a loss. The 1st respondent Company's assets were valued at less than half of its total liabilities. Its financials did not generate confidence. There was also the possibility of the 1st respondent Company's directors being in a position to withdraw the whole sum of money to pay creditors, pay themselves or otherwise make risky investments that could yield negative returns, at any time once the judgment debt was paid directly to the 1st respondent. (paras 46, 49, 50 & 51)

(6) The Court should not ignore the reality of the ease with which money might be withdrawn from a company's account. It was a factor to be considered where the financials of the company was not promising and precarious. In the instant case, while the situation might not have justified a complete stay of the execution of the judgment sum, the Court had to explore whether the circumstances would justify a partial stay and if so on what terms or conditions, such that neither the appellants as judgment debtor nor the 1st respondent company as judgment creditor would be unduly prejudiced while awaiting the outcome of the appeal filed. (paras 52 & 64)

(7) The fact that an investment holding company was being used as a vehicle to participate in a joint-venture where the business activities with its corresponding risks and returns were being carried, did not by itself give rise to any adverse inference that the investment holding company was more susceptible to being used as a vehicle for fraud against creditors. The Court could appreciate the appellants' concerns that the 1st respondent Company as an investment holding company did not have much of a positive cash flow, an unusually low issued capital and a negative balance with a retained loss in its account though it had survived and kept afloat in litigating and defending claims. The Court could not also ignore the case with which money paid into the 1st respondent Company could be transferred out, having regard to its weak financials and that it was a private limited company with the 2nd and 3rd respondents holding two-thirds of its shares, being able to give instructions to its bank to pay out the money. Although the circumstances might not justify an unconditional stay, the Court would in the exercise of its discretion explore whether a conditional stay of either the whole or part of the judgment debt was justified and what conditions should be fair and reasonable having regard to all relevant factors. (paras 55, 61, 62 & 64)

(8) Whilst it was natural to fear that the higher the amount of the judgment debt ordered to be paid to the judgment creditor, the greater the risk of such amount being irrecoverable or being used for risky investments, one could not equate possibility with probability. The fact that the judgment debt was an enormous sum of money was by itself not a "special circumstance" that would justify a stay of the whole judgment sum from being paid. (paras 66-67)

(9) Although the concerns raised by the appellants could not justify a total unconditional stay of execution of a judgment debt, they were nevertheless valid concerns that the Court had to address. Whilst the Court could not entertain the merits of the appeal, the Court had to accept that there were appeals that were successful with the trial court held to be wrong and the judgment set aside, resulting in the need to refund the judgment sum paid earlier on a failure to get an unconditional stay of execution of the judgment debt. A successful litigant on appeal ought not to suffer any damage, prejudice and injustice due to the fact that the judgment sum paid earlier could not after the appeal be recovered. Mere assurances that the judgment sum would be safe would not be sufficient and what was required was a more tangible assurance that what was paid would be recoverable. In such instance, the Court would need, having regard to the realities of the circumstances and the rights, interests, needs and concerns of the parties, to explore factors that it might have regard to for a conditional stay that would promote business efficacy and prevent money paid from being irrecoverable. (paras 84, 85 & 90)

(10) The Court would order a sum of RM10m to be deducted from the sum of RM22m (the judgment sum) and paid at the moment with the balance stayed pending appeal. It would be fair and reasonable for half of the balance judgment sum (RM5m) to be released to the 1st respondent Company for it to pay its just debts and expenses incurred and to act in its best interest. The sum of RM5m ought to be released against the undertaking of the 1st respondent company and its two directors (the 2nd and 3rd respondents). The undertaking should be given to the Court to refund the said sum (RM5m) or so much of it as ordered by the Court after its decision in the pending appeal. An undertaking by the 1st respondent company and its two directors given to the Court to so pay when required by the Court would address the concerns of the appellants on the difficulty or impossibility of recovery. There would also be the sanction of contempt of court in the event the undertaking given to the Court was breached. (paras 102, 103, 104, 105 & 107)

(11) The other half RM5m ought to be held by the respondents' solicitors as stakeholders. There would be no difficulty of the said sum (RM5m) being repaid to the appellants should the Court of Appeal decide in favour of the appellants or so much of it as it may decide. The sum of RM5m paid to the respondents' solicitors ought to be kept in an interest earning Fixed Deposit account which interest to go to the winning parties on appeal. (paras 108-109)

(12) The balance judgment sum (RM12m) plus interest ought to be stayed pending disposal of the appeal. If the RM10m as ordered was not paid within 60 days of the Court's instant order, there would be no stay of execution of the whole of the judgment debt plus interest. If the undertakings by the 1st respondent company and its two directors were not forthcoming, the sum of RM5m ought not to be released to the 1st respondent company by the respondent's solicitors. (paras 111-112)

(13) With regards to NU5 - the stay application with respect to payment of costs, there were no special circumstances to justify a stay. The application thus ought to be dismissed with costs. (paras 114-115)

Case(s) referred to:

Akitek Tenggara Sdn Bhd v. Mid Valley City Sdn Bhd [2007] 2 MLRA 584 (refd)

A-G v. Emerson [1889] 24 QBD 56 (refd)

Caucasia Sdn Bhd v. Malaysia National Insurance Berhad & Anor [2009] 8 MLRH 642 (refd)

Che Wan Development Sdn Bhd v. Co-Operative Central Bank Bhd [1989] 1 MLRH 267 (refd)

Dato' V Kanagalingam v. David Samuels & Ors [2006] 1 MLRH 679 (refd)

Econpile (M) Sdn Bhd v. IRDK Ventures Sdn Bhd [2016] 5 MLRH 282 (refd)

F Hoffmann-Roche & Co AG & Ors v. Secretary of State for Trade and Industry [1975] AC 295 (refd)

GS Gill Sdn Bhd v. Descente Ltd [2010] 1 MLRA 483 (refd)

Jaya Harta Realty Sdn Bhd v. Koperasi Kemajuan Pekerja-Pekerja Ladang Bhd; Tetuan Isharidah, Ho, Chong & Menon (Garnishee) [2000] 1 MLRH 316 (refd)

Kosma Palm Oil Mill Sdn Bhd & Ors v. Koperasi Serbausaha Makmur Bhd [2003] 1 MLRA 536 (folld)

Ming Ann Holdings Sdn Bhd v. Danaharta Urus Sdn Bhd [2002] 1 MLRA 214 (refd)

Omex Shipping Co Ltd v. World Aero Supplies Pte Ltd & Anor [1986] 2 MLRH 485 (refd)

Sarwari Ainuddin v. Abdul Aziz Ainuddin [1995] 4 MLRH 388 (refd)

Sohan Singh v. Gardner & Anor [1962] 1 MLRH 251 (refd)

Tan Poh Lee v. Tan Boon Thien [2022] 2 MLRA 329 (refd)

Walter Pathrose Gomez & Ors v. Sentul Raya Sdn Bhd [2005] 2 MLRH 647 (refd)

Wilson v. Church (No 2) (1879) 12 Ch D 454 (refd)

Wimbledon Construction Company 2000 Ltd v. Vago [2005] EWHC 1086 (TCC) (QBD) (refd)

Wu Shu Chen (Sole Executrix Of The Estate Of Goh Keng How, Deceased) v. Raja Zainal Abidin Raja Hussin & Anor [1995] 4 MLRH 45 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Companies Act 1965, s 181

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, ss 43, 44, 73

Rules of Court 2012, O 45

Rules of the High Court 1980, O 47 r 1(1)

Counsel:

For the appellants: Gopal Sri Ram (James Ee Kah Fuk, S Preakas, Malar Loganathan, Yasmin Soh & Manpil Singh with him); M/s KF Ee & Co

For the respondents: Prem Ramachandran (David Mathews & Roobini Stephanie Sittampalam with him); M/s Kumar Partnership

JUDGMENT

Lee Swee Seng JCA:

[1] This judgment of the Court explores whether "special circumstances" exist under which the execution of payment of a judgment debt may be stayed unconditionally and if not, whether there are factors that the Court may nevertheless have regard to that may justify a conditional stay of either the whole or part of the judgment sum pending the disposal of an appeal.

[2] The appellants were dissatisfied with part of the judgment of the High Court which heard their related disputes with the respondents in some suits consolidated and heard together. They have thus filed two applications both in encl 4 in NU 4 for Civil Appeal No: W-02(NCC)(W)-1528-08-2021 and NU5 for Civil Appeal No: W-02(NCC)(W)-1595-08-2021 to stay the execution of the judgments of the High Court below where the appellants had filed two separate appeals to the Court of Appeal.

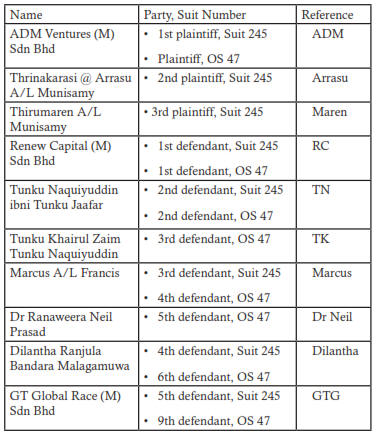

[3] The appellants may be collectively and conveniently referred to as the Renew Capital (M) Sdn Bhd's parties or "RC Parties" and the respondents as the ADM Ventures (M) Sdn Bhd's parties or the "ADM Parties". A helpful summary of the parties prepared by the appellants' solicitors as they appeared in the High Court is set out in the table below; encapsulating the enmeshment of a ruptured business joint-venture:

[4] Suit 245 is Suit No: WA-22NCC-245-06-2016 in the Kuala Lumpur High Court where the plaintiffs there are ADM, Arrasu and Maren as the 1st to the 3rd plaintiffs respectively and RC, TN, Marcus, Dilantha and GTG are the 1st to the 5th defendants respectively.

[5] OS 47 is Originating Summons No: WA-24NCC-47-02-2016 in the Kuala Lumpur High Court where ADM is the plaintiff and the RC, TN, TK, Marcus, Dr Neil, Dilantha, Faizal Maulana bin Hassan Kutti, City Motorsports Sdn Bhd and GTG as the 1st to the 9th defendants respectively.

[6] For the purpose of the application in NU 4, only OS 47 is relevant and is the more substantial application involving a stay of the execution of the monetary judgment of RM22,666,195.16 by the appellants with respect to payment of the judgment sum to ADM. This was a claim brought by ADM pursuant to s 181, Companies Act 1965 in respect of GTG. GTG is a company in which both RC and ADM hold 50% of the shares.

[7] The High Court allowed OS 47, concluding that several grounds of oppression had been made out by ADM. On that basis, the learned Judge ordered that GTG be wound-up (as a remedy for oppression) and further ordered the appellants to pay a sum of RM22,666,195.16 to ADM with a global cost of RM500,000.00. The appellants filed their appeals on 11 August 2021 in W-02(NCC)(W)-1528-08/2021. The appellants there are RC, TN, TK, Marcus and Dr Neil as the 1st to the 5th appellant respectively. The respondents in the appeal are ADM and GTG.

[8] In NU 4 the Notice of Motion filed is for stay of the execution or enforcement of the monetary part of the judgment of the High Court pending the disposal of their appeal in the Court of Appeal. The said judgment was delivered in respect of Suit 245 and OS 47 in the High Court, which were heard together.

[9] NU5 is another application filed for stay of execution with respect to a much lesser sum in the costs awarded against the appellants in a series of inter-related suits heard together in the High Court below wherein costs of RM100,000.00 had been awarded against the appellants for the dismissal of their claims against the respondents for which an appeal in W-02(NCC)(W)- 1595-08-2021 had been filed for appeal to the Court of Appeal.

[10] The relevant suits heard together were Suit No WA-22NCC-19- 01/2016 ("Suit 19"), Suit No WA-22NCC-34-01-201 ("Suit 34") dan Suit No: WA- 22NCC-272-08-2016 ("Suit 272"). For the purpose of the application before this Court, only Suit 19 is relevant. This was a claim brought by RC and TN for RM8.5 million against Arrasu and Maren for wrongfully inducing RC and TN into advancing RM8.5 million to GTG on the representation that ADM would reciprocate by advancing the same amount. RC and ADM each held 50% of the shareholding of GTG. This claim was dismissed together with the other claims of the RC Team and a global cost of RM100,000 was ordered to be paid to the ADM Parties jointly by RC, TN, TK, Marcus and Dr Neil jointly and severally in the Court Order dated 30 July 2021.

[11] The appellants there are RC and TN as the 1st and 2nd appellants respectively while the respondents are Arrasu and Maren as the 1st and 2nd respondents respectively.

[12] The two appeals are still at an early stage of case management and there have been no hearing dates fixed for the appeals as yet. The question is whether there are special circumstances warranting a stay of execution/enforcement of the judgments of the High Court pending the determination of the underlying appeals.

[13] The appellants had made a prior application in the High Court for a similar stay of execution of the judgment. That application was concerned with all monetary orders made in Suit 245 and OS 47. Apart from the damages awarded above, costs amounting to RM500,000.00 were awarded to ADM, Arrasu and Maren jointly in respect of both suits. That application was dismissed by the High Court on 28 September 2021.

[14] There was also a similar application made with respect to the stay of the payment of the costs of RM100,000.00 in Suit 19 heard together Suit 34 and Suit 272 which had also been dismissed by the High Court on 28 September 2021.

[15] As the two applications for stay emanating from the two separate appeals were heard together in NU 4 and NU5, the parties shall generally be referred to collectively as the appellants and the respondents and where necessary by their acronyms or abbreviated names.

The Law On "Special Circumstances" Justifying An Unconditional Stay Of The Payment Of The Judgment Debt

[16] The expression "special circumstances" appeared as far back as the Rules of High Court 1980 in O 47 r 1(1) and it is also the same provision in the current Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC 2012") as follows:

"O 47 r 1 Power to stay execution by writ of seizure and sale:

1(1) Where a judgment is given or an order made for payment by any person of money, and the Court is satisfied on an application made at the time of the judgment or order or at any time thereafter, by the judgment debtor or party liable to execution:

(a) that there are special circumstances which render it inexpedient to enforce the judgment or order; or

(b) that the applicant is unable from any cause to pay the money;

then, notwithstanding anything in r 2 or 3, the Court may by order stay the execution of the judgment or order by way of seizure and sale either absolutely or for such period and subject to such conditions as the Court thinks fit."

[Emphasis Added]

[17] The Court has a discretion as to whether to grant or not to grant a stay of execution of a judgment pending appeal depending on whether there are special circumstances, which circumstances must be deposed to on the affidavits supporting the application and refuting the objection to the stay. It also has a discretion to impose conditional stay subject to terms of the whole or part of the judgment sum ordered to be paid. Granted the expression "special circumstances" was used with reference to stay of the mode of execution by way of a writ of seizure and sale.

[18] Generally, an appeal does not operate as a stay of execution of the payment of the sum adjudged to be paid by a judgment of the Court unless the High Court that granted the judgment or the Court appealed to in the Court of Appeal so orders. Under s 43 of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 ("CJA") any stay application has to be made to the High Court first which had been made and dismissed by the High Court. Section 73 of the CJA provides as follows:

"73. Appeal not to operate as stay of execution

An appeal shall not operate as a stay of execution or of proceedings under the decision appealed from unless the court below or the Court of Appeal so orders and no intermediate act or proceeding shall be invalidated except so far as the court of Appeal may direct."

[Emphasis Added]

[19] The discretion is thus reposed with the Court and like all judicial discretion, it must be exercised with reference to established principles of law and not arbitrarily. The power of the Court of Appeal generally to preserve status quo and to prevent prejudice to the claims of parties pending the hearing of an appeal is also found in s 44 of the CJA as follows:

"Incidental directions and interim orders

44. (1) In any proceeding pending before the Court of Appeal any direction incidental thereto not involving the decision of the proceeding, any interim order to prevent prejudice to the claims of parties pending the hearing of the proceeding, any order for security for costs, and for the dismissal of a proceeding for default in furnishing security so ordered may at any time be made by a Judge of the Court of Appeal."

[Emphasis Added]

[20] Thus in A-G v. Emerson [1889] 24 QBD 56 it was spoken by Lord Esher MR at p 58 as follows:

"The real question is, what is the construction of this rule? It says:

'An appeal shall not operate as a stay of execution or of proceedings under the decision appealed from, except so far as the court appealed from, or any judge thereof, or the Court of Appeal, may order; and no intermediate act or proceeding shall be invalidated, except so far as the court appealed from may direct.' In all the rules the word "may" has been held to mean "may or may not". It has been held to give a discretion, which is called a judicial discretion, but is still a discretion."

[21] Therefore, in finding whether or not "special circumstances" exist, the Court shall have regard to all relevant factors and shall not take into consideration irrelevant factors, bearing in mind the basic general principles and the exceptions to it.

[22] The approach to be taken in all cases of a stay of execution of a judgment of the Court below is that the merits or the lack of it is not a relevant consideration at the stage of a stay of execution of the judgment below. Thus, whether an appeal is doomed to fail or bound to succeed is of no relevance as these are matters to be considered in the appeal proper and not in a stay of execution of the judgment of the Court below.

[23] This approach is captured in the Court of Appeal case of Ming Ann Holdings Sdn Bhd v. Danaharta Urus Sdn Bhd [2002] 1 MLRA 214, Abdul Hamid Mohamad JCA (later CJ) said:

"I agree that in an application for a stay of execution, that the appeal, if successful, would be rendered nugatory is the 'paramount consideration' or by whatever name it is called. And, I do not think that it matters whether it is considered under the head of 'special circumstances' or not, so long as it is considered and so long as he does not go so far as to say that no other factors may be considered because this is an exercise of discretion, and therefore all the relevant factors should be considered.

My difficulty with See Teow Guan, if it were to be applied to an application for a stay of execution, is that the learned judge found that the appeal would be rendered nugatory because it is doomed to failure. As I understand it, the nugatory test that the courts talk about in an application for a stay of execution goes to the subject matter of the case, not the merits of the appeal. In other words, the appeal, if successful, is worthless because the appellant cannot be put in its former position. That 'the appeal is doomed to failure' in my view, goes to the merits of the appeal, not to the execution."

[Emphasis Added]

[24] Thus it has been said ever so often that a successful litigant is generally not to be deprived of the fruits of his litigation. The law does not require that the unsuccessful litigant who is minded to appeal must be allowed to exhaust all avenues and tiers of appeal before the successful litigant, armed with a judgment of the Court, especially for the payment of a judgment debt, may proceed with the execution of the judgment debt.

[25] If a stay is invariably granted merely because there is an appeal which may reverse the finding of the trial court and thus which appeal may be allowed and the judgment of the trial court or of the first instance, set aside - then we would have a situation that by the time the various tiers of appeals are exhausted, there may not be anything left for the successful litigant to execute on. Much costs and expenses would have been spent by the unsuccessful litigant in exhausting all avenues of appeal, only to drag and delay the successful litigant from recovering the judgment debt. This is not to mention that in cases of an unscrupulous litigant, there could be more than ample opportunities to dissipate whatever assets it has so as to make itself judgment-proof.

[26] Having said that, there are also cases where a judgment debt is set aside on appeal for there are many cases too where appeals have been allowed with the result that if the judgment debt had already been paid, the process to recover it back from the respondent in the appeal may prove time-consuming, costly and even difficult, if not, impossible - a fruitless exercise as the judgment debt paid may have been dissipated and squandered.

[27] We all know that there are various modes of execution available under the Rules of Court 2012 such as a writ of seizure and sale, a prohibitory order followed by sale of the debtor's landed assets, a garnishee order absolute, a charging order absolute, to name but a few. See generally O 45 ROC 2012. Then there are other modes of recovery of debts (though not called a mode of execution) such as bankruptcy proceedings against an individual for him to be adjudged a bankrupt or winding-up proceedings in the case of a company debtor being unable to pay its debts - all these may still yield a negative return with the amount paid being irrecoverable.

[28] It is true that often times the Court in hearing a stay application would have to balance the competing rights, interests, needs and concerns of the parties and maintain a dynamic balance of the competing concerns so that no one should be deprived of its fruits of litigation be it having succeeded at the trial court or having lost at the trial court but succeeded in the appellate court on appeal. The party that first succeeded at the trial court would want an immediate bite on the assets of the losing party. Likewise, the losing party who succeeds on appeal would want to have an equally effective bite to successfully recover what has been paid.

[29] Thus whilst the successful party at first round is concerned that its judgment is recoverable immediately, the unsuccessful party who may well succeed on appeal is equally concerned that its successful appeal should not be nugatory in that whatever has been paid would be repaid back. His argument is that the appellate court's judgment is the ultimate correct judgment and if the judgment of the court of first instance has been set aside, then all the more reason to say that the judgment sum had been paid under a mistaken judgment of the court below which has been duly set aside upon a successful appeal.

[30] A grave injustice would have been done to the successful appellant if it is not able to recover back what it has paid because the execution of a judgment debt granted by the court of first instance was not stayed. Either side that has won at whichever tier of appeal is equally concerned that it should not be deprived of its fruit of litigation and more so the ultimate winning party in the various tiers of appeal that are available.

[31] This dilemma was captured in the dicta of Vincent Ng J (later JCA) in Jaya Harta Realty Sdn Bhd v. Koperasi Kemajuan Pekerja-Pekerja Ladang Bhd; Tetuan Isharidah, Ho, Chong & Menon (Garnishee) [2000] 1 MLRH 316, where His Lordship observed thus:

"The justice of the case on stay is arrived at by striking a judicious and equitable balance between the principle that the successful party in the litigation ought to be allowed to reap the fruits of that litigation and not obtain a mere barren success, and the countervailing principle that should the unsuccessful party in litigation be ultimately successful in his appeal, he ought not be deprived of the fruits of his litigation due to the result of his appeal being rendered nugatory."

[32] Courts have increasingly been more inclined to explore a partial conditional stay upon terms to balance the competing rights, interest, needs and concerns of the parties without offending the general principle that generally a party a successful litigation even at first instance is entitled to the fruit of its litigation unless "special circumstances" can be shown by the unsuccessful party that is appealing.

[33] The law on stay of execution of a monetary judgment is trite in that the Court may exercise its discretion to grant a stay of execution of the judgment debt if the judgment debtor as the applicant in the stay application could show "special circumstances" relating to the enforcement of the judgment pending appeal. It is an accepted "special circumstance" if the appeal were to succeed, the appeal would nevertheless be nugatory if the successful appellant would be deprived of the result of the successful appeal that would have set aside the payment of the judgment debt or so much of it.

[34] We need not go before or beyond the Federal Court case of Kosma Palm Oil Mill Sdn Bhd & Ors v. Koperasi Serbausaha Makmur Bhd [2003] 1 MLRA 536 for a restatement of the principle governing the exercise of the Court's discretion to grant a stay as articulated by, Augustine Paul JCA (as he then was) as follows:

"[7] The general rule is that an appeal shall not operate as a stay of execution unless the Court so orders. Accordingly, as Brown J said in Serangoon Garden Estate Ltd v. Ang Keng [1953] 1 MLRH 690 while commenting on the discretion to grant a stay:

But it is a clear principle that the Court will not deprive a successful party of the fruits of his litigation until an appeal is determined, unless the unsuccessful party can shew special circumstances to justify it.

[8] This is a re-statement of the common law rule explained in The Annot Lyle [1886] 11 PD 114 where Lord Esher MR said at p 116:

... that an appeal shall be no stay of proceedings except the court may so order. We are asked to depart from this rule, although it is admitted that there are no special circumstances in this case which afford a ground for so doing. If in any particular case there is a danger of the appellants not being repaid if their appeal is successful, either because the respondents are foreigners, or for other good reason, this must be shewn by affidavit, and may form a ground for ordering a stay. To grant the present application would, in the absence of special circumstances, clearly be to act contrary to the provisions and intention of the Rules of Court."

[Emphasis Added]

[35] A common example would be a case of land where specific performance is granted but that there is a pending appeal which if successful would have the effect of setting aside the specific performance order. However, if there had been no stay of execution of the judgment of the Court, the land may be sold and transferred to a third party who may have purchased it in good faith and for valuable consideration and the land may then have been charged to a bank by the third party. Thus the successful appellant's appeal is said to be nugatory for he cannot get the land back and may only have to settle for damages.

[36] The above example is with respect to a specific performance order rather than a stay of execution for the payment of a judgment debt and that is because it is relatively rare that a successful appeal from the payment of a judgment debt would be rendered nugatory as the successful appellant has all the methods of execution available to him under the Rules of Court 2012 to effect recovery of the judgment debt if payment had already been made to the judgment creditor which judgment has been set aside on appeal.

[37] However there may well be circumstances that would render recovery of a judgment debt paid a near impossibility because either the judgment creditors are many and scattered all over the world and mainly in a foreign state or that there is evidence that the judgment creditor is not able to repay as it is insolvent or near insolvent or already in liquidation or on the threshold of it or that there is a real likelihood and danger of dissipation of the judgment debt paid. See the cases of Che Wan Development Sdn Bhd v. Co- Operative Central Bank Bhd [1989] 1 MLRH 267 and Sarwari Ainuddin v. Abdul Aziz Ainuddin [1995] 4 MLRH 388.

[38] Learned counsel for the appellants also referred to the following cases as supporting the proposition that there is nothing wrong in law to stay even the execution of the award of costs based on the same reasons as a stay of execution of a judgment debt: Sohan Singh v. Gardner & Anor [1962] 1 MLRH 251 (High Court Singapore) and Omex Shipping Co Ltd v. World Aero Supplies Pte Ltd & Anor [1986] 2 MLRH 485 (High Court Singapore).

[39] There are various factors that the Court may consider in the exercise of its discretion to grant a stay, whether it be unconditional or conditional. It involves a fine balancing exercise in weighing and considering the relevant factors for and against a stay and if conditions are imposed, the reasonable conditions having in mind the rights, interests, needs and concerns of the parties. The various factors shall be considered below.

Whether The Poor Financial Position Of The Judgment Creditor Constitutes A "Special Circumstance" In The Circumstances Of The Case?

[40] It was contended before us that the financial position of the judgment creditor ADM is such that it would not be able to repay back the judgment sum if paid before the appeals to the Court of Appeal are heard.

[41] This, the appellants submitted, will render their appeals nugatory as any execution taken against ADM would be an exercise in futility and even if ADM were to be wound up on account of its inability to pay back the judgment debt, that would not yield any positive return.

[42] The respondents on the other hand argued that there is no evidence of ADM's insolvency in that there has not been any winding-up petition filed against ADM and that all demands for payments of debts have been met. Whilst it is not disputed that the financial position of ADM does not look promising, the respondents explained that such an unhealthy financial position was caused by the RC Team's breaches of their joint-venture agreement with ADM such that the High Court after having made a finding of fact on liability, proceeded to assess damages for the loss suffered by ADM to the tune of RM22 million.

[43] That being the case, it was urged upon this Court, that the current financial position of ADM is attributed to the appellants and surely the RC Team should not be allowed to benefit from its own breach. The principle that a person cannot rely on his own wrongdoing to obtain a benefit or an advantage has been clearly enunciated by the Federal Court in Akitek Tenggara Sdn Bhd v. Mid Valley City Sdn Bhd [2007] 2 MLRA 584 at para 53. See also Dato' V Kanagalingam v. David Samuels & Ors [2006] 1 MLRH 679 (HC), para 15.

[44] Learned counsel for the respondents also cited cases from the adjudication regime under the Construction Industry Payment and Adjudication Act 2012 ("CIPAA") where a stay would not be granted of an Adjudication Decision if it can be shown that the cause of the claimant's financial predicament is because of the non-payment by the employer applying for a stay on account of its non-payment for work done by the claimant contractor. See Econpile (M) Sdn Bhd v. IRDK Ventures Sdn Bhd [2016] 5 MLRH 282 (HC) that followed the principle laid down by Peter Coulson QC in Wimbledon Construction Company 2000 Ltd v. Vago [2005] EWHC 1086 (TCC) (QBD) where it was held that the defendant cannot rely on the claimant's financial state to suggest its inability to repay the judgment sum if the claimant's financial position was largely the defendant's own fault.

[45] Whilst we have no problem with the principle propounded in the context of CIPAA cases, we appreciate that the CIPAA regime was introduced to alleviate the problem of cash flow of the contractors for work done for which they have not been paid and so are out of pocket where costs of labour, materials and workmanship are concerned. To allow a stay of an Adjudication Decision might well work against the purpose of the CIPAA in the first place.

[46] Generally the impecuniosity or precarious financial position of the successful litigant is, not by itself, a "special circumstance" justifying an unconditional stay of the whole of the judgment debt required to be paid. In Che Wan Development Sdn Bhd v. Co-Operative Central Bank Bhd [1989] 1 MLRH 267, NH Chan J (as he then was) observed as follows:

"Insolvency (even if it can be established, but it has not been established in the present case) or the poverty of the plaintiff by itself is not a special circumstance for staying execution of a judgment in favour of the plaintiff except in the case of a money judgment (which this case is not) and where it has been deposed to on affidavit that there was no reasonable probability of getting the money back after it had been paid over if the appeal succeeded as shown in the three cases which I have referred to ( Atkins v. GW Ry [1886] 2 TLR 400, Barker v. Lavery [1885] 14 QBD 769 and The Annot Lyle [1886] 11 PD 114 ..."

[Emphasis Added]

[47] It was held in Sarwari Ainuddin v. Abdul Aziz Ainuddin [1995] 4 MLRH 388 (HC) that impecuniosity alone of the judgment creditor is not good enough to obtain a stay and that evidence must be led that the judgment creditor would not be able to repay when ordered to do so on appeal. Mahadev Shankar J (later JCA) observed at pp 389-390 as follows:

"It is not enough to contend that the plaintiff is impecunious and therefore incapable of making reimbursement. Evidence has to be adduced to prove that it is so ...

In his affidavit, the defendant says the plaintiff is unemployed, does not own any property of any sufficient value and therefore the appeal will be nugatory. Other grounds urged are that she waited 41 years to make her claim and she would not be prejudiced if she waits a little longer.

The plaintiff 's response is that although she is unemployed she is not a pauper. She avers that she has financed this litigation both in terms of legal expenses and valuation reports. She further avers that she did not at any time tell the defendant about her financial condition. She thus leaves it to be implied that the defendant's assertion that she does not own any property of value, is pure speculation. But she has not listed any of her assets. She also claims that if the defendant's claim is allowed, the result will be that the denial of justice which she has suffered all these years will be further perpetuated.

Charting a course between these contentious submissions, I would observe first of all that the onus of showing that the appeal will be nugatory unless the stay is granted is upon the defendant. It is not enough to say that the plaintiff is poor. It has also to be shown that if the money is paid over there is no reasonable probability of getting it back."

[Emphasis Added]

[48] The above case of Sarwari (supra) was cited with approval in the Federal Court case of Kosma Palm Oil (supra). Learned counsel for the respondents also cited the case of Walter Pathrose Gomez & Ors v. Sentul Raya Sdn Bhd [2005] 2 MLRH 647 at pp 654-655 where it was observed as follows:

"[24] I must categorically say that the defendant's assertion on the plaintiffs' so called 'poverty' was a one liner assertion and a bare averment unsupported by any evidence. It was purely speculative because the defendant makes reference to the poverty point only at that para 5(b) of encl 11. There was no evidence, at all that the plaintiffs are insolvent and are not in a position to reimburse the liquidated and ascertained damages in the event the defendant succeeds in the appeal in the Court of Appeal. Thus, if a stay was allowed as sought for by the defendant it would send a wrong signal to those parties who lost their cases upon the merits by wrenching the fruits of litigation from the successful parties by adopting dubious methods of keeping the litigation alive through spurious appeals without any real prospect of success and simply in the hope of gaining some respite against immediate execution on the judgment. It has become fashionable to make an assertion, without affidavit evidence, that the successful party would not be in a position to reimburse the judgment sum. The court would certainly decline to accept assertions from the bar without support from affidavit evidence."

[49] This Court is not unmindful of the fact that we are all not immune to the temptations that a huge sum of money would pose such as a sum of RM22 million sitting in the coffers of ADM and when faced with a tight financial straits situation where the company is running at a loss and where the paid up capital does not engender confidence.

[50] The issued share capital of ADM is a mere RM100.00. The total value of its assets as at 28 October 2021 is RM204,757.00, which is less than half of its total liabilities of RM472,709.00. The financials do not generate confidence.

[51] There is also the reality of directors of the company being in a position to withdraw the whole of the money out to make payments to creditors or to pay themselves or otherwise make risky investments that may yield a negative returns. Merely because none of these have been done before cannot shut the possibility that it can be done at anytime once the judgment debt is paid directly to ADM.

[52] This is where the Court cannot ignore the reality of the ease with which money could be withdrawn from a company's account. It is a factor to be taken into consideration where the financials of the company is not promising and indeed precarious. While the situation may not justify a complete stay of the execution of the judgment sum, this Court must nevertheless explore whether the circumstances would justify a partial stay and if so on what terms or conditions such that neither the appellants as judgment debtor nor the respondent ADM as judgment creditor would be unduly prejudiced while awaiting the outcome of the appeal filed.

Whether The Fact That ADM Is An Investment Holding Company And Otherwise Dormant And Holding The Shares In The JV Company GTG Would Constitute A "Special Circumstance"?

[53] It was further impressed upon us that ADM is a dormant company and that it had no business other than holding the shares of GTG. Hence ADM is the corporate vehicle of Arrasu and Maren. The appellants pointed out that in his affidavit on behalf of the respondents, Maren admitted that "ADM is an investment holding company incorporated specifically to spearhead the operations and management of GTG. ADM held a 50% ownership stake in GTG which constituted its primary asset."

[54] It is a fact that GTG was however wound up by the High Court in OS 47. Apparently, it was the appellants who had submitted that, in light of the finding of the learned High Court Judge that oppression had been made out, winding-up GTG was the only appropriate relief. ADM did not appeal against the winding-up of GTG. Thus, the appellants concluded that, as things stand, shares in GTG are not of any value.

[55] The fact that an investment holding company is being used as a vehicle to participate in a joint-venture where the business activities with its corresponding risks and returns are being carried, does not by itself, give rise to any adverse inference that the investment holding company is more susceptible to being used as a vehicle for fraud against creditors. Investment is after all a kind of business activity and like all other businesses, it may yield a positive or negative return. Depending on the type of investments, one may manage risk by putting one's eggs in different baskets to spread out one's risks.

[56] Whilst ADM's shares in GTG may be quite worthless now that GTG had been wound up, yet there is a sum to the tune of RM22 million due to the company ADM. What is owing to ADM is in accounting terms part of the assets of the company. Where and how it may want to invest this sum of about RM22 million is a matter which ADM would have to decide in the best interest of the company.

[57] One may even argue that the costs of running an investment company is more or less predictable and can be easily budgeted for whereas in a company that is running a business, there is always the need to manage one's costs, production, sales, marketing and collection and past performance is no guarantee for future returns and that if there is a reasonable track record stretching back a few years, that may engender confidence in creditors. It must be borne in mind that companies are incorporated so that individuals who pool their resources together in subscribing to the shares are personally not exposed to liability and that the debt is that of the company and not its shareholders. It is a way to buffer business risks in ventures that may prove to be risky without personally being exposed to liability other than to have one's investment in the company to be completely wiped out if the company suffers a winding-up.

[58] Similar concerns had been raised in Caucasia Sdn Bhd v. Malaysia National Insurance Berhad & Anor [2009] 8 MLRH 642 (HC) where the 1st defendant applied to stay the execution of a judgment on the basis that the plaintiff company was dormant, running at a loss and had a negative asset. Counsel for the plaintiff argued as follows:

"No evidence that company is insolvent. The only allegation is that the company is dormant although the latest account in Exhibit "D-4" shows a debit of RM13,860.00 and this does not necessarily show(s) the company is insolvent. No demand has been made on the company that it cannot pay its debt and liability which would be evidence of insolvency."

[59] Kang Hwee Gee J (later JCA) held at pp 642-643:

"I would accept the submission of the counsel for the plaintiff that the plaintiff in this case is not insolvent or impecunious. The small negative balance in its closing account for the year 2002 could only be due to its business being dormant, and certainly not by design - given the fact that its only aircraft had been destroyed. It can be reasonably supposed that the small negative balance would have to be incurred due to the fact that some administrative expenses such as payments to its company secretary, fees, etc would have to be expended to keep a company alive for so many years without income.

... There is no special circumstance to merit a stay.

The 1st defendant's application is dismissed with costs."

[60] As ADM was the vehicle set up and principally run by its two Malaysian directors, Arrasu and Maren, and as the joint-venture with RC had imploded with multiple suits and actions between the two companies and their principal players, it is not surprising that ADM has been dormant in its investment activities. However, it is active nevertheless as can be seen in its sometimes being on the offensive when commencing actions against the RC Parties with its related persona and sometimes defending actions brought about by the RC Parties.

[61] We can nevertheless appreciate the concerns of the appellants that ADM as an investment holding company does not have much of a positive cash flow and an unusually low issued capital of RM100.00 and has a negative balance with a retained loss of RM268,052.00 in its account though it has survived and kept afloat so far in litigating its claims and defending claims made against it.

[62] This Court is fully conscious of the fact that money, and a huge sum at that to the tune of about RM22 million is a temptation to both the rich and the poor. The ease with which the money paid into ADM may be transferred out cannot be ignored by the Court having regard to its financial position that is less than promising with its accounts being in the negative and being a private limited company with its two directors in Arrasu and Maren as shareholders of two-thirds of the shares in ADM, payments may be made out as easily as the directors may sign the cheques or give the necessary instructions to its bank.

[63] We are familiar that in operating a company, especially an investment holding company, money may only be paid out via dividends declared, capital reduction, to meet demands by creditors or to pay what is outstanding to directors as well as to make wise investments. The thing is that there are hardly any checks and balances where both the directors have a controlling majority of two-thirds of the shares of the company ADM and another director Dilantha, a Sri Lankan who did not appear at the trials, is nowhere to be found.

[64] Whilst the circumstances may not justify an unconditional stay, nevertheless the Court in the exercise of its discretion may explore whether the circumstances may justify a conditional stay of either the whole or part of the judgment debt and if so the conditions that may be fair and reasonable having regard to all relevant factors.

Whether There Is A Likelihood Or Real Danger Of The Judgment Debt Paid Being Dissipated And Becomes Irrecoverable Thus Constituting A "Special Circumstance"?

[65] The appellants also contended that the sum to the tune of RM22 million if paid, would be dissipated by ADM through its directors as the company has no other assets other than a miserable paltry sum left in the bank account of the company as reflected in the accounts of the company in its annual report exhibited.

[66] It may be natural to fear that the higher the amount of the judgment debt ordered to be paid to the judgment creditor the greater the risk of the amount being irrecoverable or the amount being used for risky investments that may yield a negative return. While it can be appreciated that no one is immune to the temptation that a huge sum of money may have on the directors of the company, one cannot equate what is possible with what is probable.

[67] The fact that the judgment debt is an enormous sum of money is, by itself, not a "special circumstance" that would justify a stay of the whole of the judgment sum from being paid. See Wu Shu Chen (Sole Executrix Of The Estate Of Goh Keng How, Deceased) v. Raja Zainal Abidin Raja Hussin & Anor [1995] 4 MLRH 45 (HC).

[68] The appellants submitted that there is a category of special circumstance that is recognised in law. The appellants highlighted that ADM is the alter ego of Arrasu and Maren who are brothers. They are two of the three directors of ADM, and together they control ADM, two-thirds of its shares.

[69] The third director and shareholder, Dilantha, is a Sri Lankan citizen. Dilantha did not appear at the trial and has, according to Maren in sworn evidence, absconded.

[70] The appellants said that they have a right to be anxious about ADM's issued capital being only RM100.00. The total value of its assets as at 28 October 2021 is RM204,757.00, which is less than half of its total liabilities of RM472,709.00. The appellants underscored that though the ADM Parties asserted that ADM's latest annual loss of RM1,280.00 is "inconsequential", no explanation had been given as to why, since incorporation, ADM has a retained loss of RM268,052.00.

[71] The appellants underlined the fact that ADM's total asset value of RM204,757.00 is only approximately 0.9% of the sum ordered to be paid to ADM. Hence the appellants tried to drive home the point that the liabilities of ADM, Arrasu and Maren are real, not hypothetical.

[72] The respondents, on the other hand, scoffed at the financial position of RC, likening it scornfully to a pot calling a kettle black! The financial position of RC appeared to be 10 times worse than that of ADM with a recorded loss of RM2.85 million as at 2016 which was the last account lodged with the Companies Commission of Malaysia. The saving grace is that liability is also affixed on the individuals apart from the company RC.

[73] The appellants also drew our attention to the fact that on 27 July 2018, judgment was entered against ADM, Arrasu and Maren as third parties in Suit No: WA-22NCVC-691-11-2016 between City Neon Contracts Sdn Bhd and GTG ("City Neon 3rd Party Suit") for breach of contract, fraud, and breach of fiduciary duty. The ADM Parties were third parties there brought in by GTG and are thus liable to GTG for a total of RM13,400,975.80, with interest of 5% p.a. until full settlement.

[74] The appellants informed the Court that the execution of the City Neon 3rd Party Suit has been stayed pending appeal. The stay was granted on 10 January 2019. The appellants believe that the appeal in the City Neon 3rd Party Suit would in all likelihood proceed before the Appeal in the present proceedings, giving rise to the risk that the monetary awards herein would be used to pay the ADM Parties' liability in the third party suit.

[75] The appellants raised their concerns that given that ADM has no business of its own, if the said sum of about RM22 million is paid to it, there is no reason for the funds to remain with it. According to the appellants, Arrasu and Maren are in a position to have ADM declare a dividend or pay out monies to third parties. It is their collective position that they should not be denied the fruits of the litigation should they succeed on appeal.

[76] The appellants concluded that this would result in the dissipation of the said monies and an inability to recover the same by the appellants. Learned counsel for the appellant referred to the English Court of Appeal's case of Wilson v. Church (No 2) (1879) 12 Ch D 454, where Brett LJ said:

"This is an application to the discretion of the Court, but I think that Mr Benjamin has laid down the proper rule of conduct for the exercise of the judicial discretion, that where the right of appeal exists, and the question is whether the fund shall be paid out of Court, the Court as a general rule ought to exercise its best discretion in a way so as not to prevent the appeal, if successful, from being nugatory. That being the general rule, the next question is whether, if this fund were paid out, the appeal, if successful, would be nugatory. Now it seems to me that, looking at this matter in the view of men of business, one cannot help seeing that if this fund is paid out it is impossible to say to whom it will be paid. It is quite true that the payments out will be to persons many of whom will never be able to be found; it is very possible, and most likely, that several of them will be abroad; it is most likely that several of them will be in America; and the practical result of paying this money out to the different bondholders, or to the persons who would be holding the bonds at the time, would be that the fund never could be got back again if the appeal were successful. Therefore, if this case is to be dealt with according to the general rule, it seems to me that the Court ought to stay the payment out of this fund."

[Emphasis Added]

[77] The facts of Wilson v. Church (No 2) can be easily distinguished as justifying a clear case of "special circumstance" that would constrain a stay of the execution of the judgment. It was to begin with, a representative action which was brought by a bond holder (Wilson) of a railway company on behalf of himself and other bond holders against the company. They were claiming that the money advanced by the bond holders should be returned to them instead of its being applied in the undertaking of the railway company. Judgment was entered for the plaintiff with costs with the result that the money should forthwith be distributed among the bond holders. However, the bond holders were very numerous and many were residing abroad.

[78] It was held by Cotton LJ at p 457 as follows:

"I am of opinion that we ought to take care that if the House of Lords should reverse our decision (and we must recognize that it may be reversed), the appeal ought not to be rendered nugatory. I am of opinion that we ought not to allow this fund to be parted with by the trustees, for this reason: it is to be distributed among a great number of persons, and it is obvious that there would be very great difficulty in getting back the money parted with if the House of Lords should be of opinion that it ought not to be divided amongst the bondholders. They are not actual parties to the suit; they are very numerous, and they are persons whom it would be difficult to reach for the purpose of getting back the fund."

[79] It was also singled out that, significantly, the ADM Parties have not alleged that they would face any difficulty enforcing judgment against RC, TN, TK, and Marcus if the Appeal is unsuccessful. In this regard, the appellants drew the Court's attention to Exhibit MF-9 of the Affidavit in support, enclosing CTOS file searches on TN (pp 258-274), TK (pp 275-283), and Marcus (pp 284-292).

[80] It was also prevailed upon us by the appellants that TN is a well- known Malaysian businessman who is a member of the royalty of Negeri Sembilan. His late father, Tuanku Ja'afar Ibni Al Marhum Tuanku Abdul Rahman, was the former Yang di-Pertuan Besar of that State and the 10th Yang di-Pertuan Agong. TN served as the Regent of Negeri Sembilan while his late father was the Yang di-Pertuan Agong. TN resides in Malaysia and has extensive business dealings here. His list of top five directorships and business interests are in, amongst others, two listed companies, Ann Joo Resources Berhad and Orix Leasing Malaysia Berhad.

[81] As for TK, he is TN's son. He also resides in Malaysia and has wide business dealings here. Marcus, on the other hand, is the business associate of TN and is involved in a range of ventures with him. He resides in Malaysia and has wide business dealings here.

[82] It is a case of the appellants telling the respondents that they should have no problem sleeping at night without being assailed by any anxieties that ADM would not be paid sooner or later, once the appeals are disposed of and the decisions of the High Court are affirmed. Thus it was submitted that as these parties are Malaysian citizens, residing in Malaysia, with extensive participation in profitable Malaysian enterprises, the ADM Parties would not be prejudiced by a stay of execution pending determination of the appeals.

[83] This Court was asked to take notice of the fact that a payment of the sum of RM22,666,195.16 would necessarily involve a significant change of position, including the liquidation of assets, the impact of which would not be remediable if the appeals are determined in favour of the appellants given the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the economy. It was further argued that it is pertinent as the central question for any court hearing an application for a stay of execution is: what if the appellate court reverses the first instance decision?

[84] The concerns raised, though cannot justify a total unconditional stay of execution of a judgment debt, are nevertheless valid concerns which this Court must address. Whilst it is not for us at this stage to enter into and entertain the merits of the appeal, we must nevertheless accept the fact that there are appeals that are successful with the result that the trial court had been held to be wrong and so the judgment set aside and with that the need to refund the judgment sum earlier paid on a failure to get an unconditional stay of execution of the judgment debt.

[85] It is a valid argument that because an appeal is allowed and the judgment of the trial Court set aside, it would mean that the judgment of the trial Court had been wrong. If there is no appeal from the appellate court, the judgment of the appellate court would be the final judgment. Why then should a successful litigant on appeal suffer any damage and prejudice on account of the fact that the judgment sum earlier paid could not now be recovered? An injustice would have been done to the ultimately successful litigant. It is not for the Court to say that it is just too bad because we cannot say with certainty what the successful litigant at the trial of first instance would do with the judgment sum it had received pursuant to a stay of execution that had been dismissed.

[86] We can appreciate the argument raised by all appellants each time a stay of execution is applied for where they have lost at the first instance. How is one to produce evidence of dissipation of assets because, if at all it should happen, it would be in the future? How can there be evidence of a matter that may or may not happen in the future?

[87] Neither can past conduct confirm what would happen in the future as in just because there had been proper management of one's account in the past, what assurance is there when a large sum of money is paid into that account, there would be no risk of it being improperly paid out? It has been often said that we are all a bundle of contradictions - doing that which is wrong in a moment of indiscretion. We can understand if there had been evidence of misappropriation or wrongful payment of money out of the accounts in the past which may give rise to a reasonable probability that the same may happen again once a much bigger sum of money has come into the accounts.

[88] Of course we can hear the successful judgment creditor in the High Court below saying that it is no business of the Court hearing a stay of execution to delve into the possibility of things happening, including possibility of the appellant succeeding and possibility of dissipation of assets and possibility of not being able to recover what may have been paid already.

[89] Human nature being what it is, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. The realities of the fact that the financials of the judgment creditor/ respondent being not promising at all and indeed precarious and the structure of the investment holding company with the two directors being able to dispose of all the assets of the company ADM with their two- thirds majority in ADM, it would be fair to say that the respondents must also put their mouths where the money is.

[90] Mere words of assurance that the sum paid would be safe is not good enough for words are cheap and one must be prepared to give a more tangible assurance that what is paid would be recoverable. This is where this Court would need, having regard to the realities of the circumstances and the rights, interests, needs and concerns of the parties, to explore factors that it may have regard to for a conditional stay that would promote business efficacy and prevent money paid from being irrecoverable when one should ultimately be successful though having lost at first instance.

Whether The Circumstances Alluded To By The Appellants Would Justify A Conditional Stay Of Execution Of The Judgment Debt?

[91] Granted it is difficult to say with any degree of certainty, even on a balance of probabilities that monies paid to ADM would or would not be paid out validly or be wrongfully dissipated. There is no evidence that monies in its account had been fraudulently paid out in the past.

[92] However the Court must always be conscious of the fact and caution itself that the danger of monies sitting in its coffers and especially a huge sum at that, may cause the directors running the company to fall for the temptation to dissipate it for one's own use such that it would be difficult if not impossible to recover it back.

[93] It is against the danger and risk posed, which we cannot pretend is not there, that this Court must explore whether some conditions may be imposed for a stay such as to address the rights, needs, interests and concerns of the parties.

[94] Though the Court cannot be blamed if it does not grant a stay and even if at the end of the day, the sum paid of about RM22 million could not be recovered should it be required to be repaid or so much of it, the Court should be concerned that the rights, interests, needs and concerns of the parties are properly addressed, such that irrespective of the result of the appeal, neither party is not unduly prejudiced.

[95] Likewise the Court in granting a stay cannot equally be blamed if at the end of the day the appeal should be dismissed and ADM could not be paid, though the appellants said this is rather unlikely for they are people whose reputation cannot afford to be sullied and whose wealth can easily be liquidated to meet the amount to be paid at the end of the day after the appeal is disposed of in the Court of Appeal.

[96] Of course we did hear the appellants saying that TN and TK are people of repute with royal blood and princely pedigree with TN having directorship of at least two public listed companies and that they are all genuine and successful businessmen whose integrity is unimpeachable and whose financial means have never been doubted. We do not think for a moment that learned counsel for the appellants are asking for special consideration on that score.

[97] This Court, like all other Courts, would give the same equal treatment to all and sundry who appear before it. Everyone is equal before the law and no one is more equal before the law and the Courts. The Courts do not take judicial notice of the wealth or poverty of a person unless there is evidence of it before the Court. If assets are disclosed then liabilities would have to be disclosed too. The Court can appreciate the sensitive nature of such information which is best left in the private domain.

[98] We get the message that learned counsel for the appellants is trying to say that the appellants would have no problem making payment of the judgment debt plus interest even now or better still, after all avenues for appeal have been exhausted. What appears to have been not said in so many words is that while the appellants have no problem paying the judgment sum of around RM22 million, the appellants have valid doubts as to the corresponding ability of the respondents to so repay the said sum if there is no stay of the execution of the judgment sum ordered by the High Court. What has been suggested by the appellants if not already specifically said is that the respondents lack financial and reputation standing and resources when compared to the appellants.

[99] To say that one has no problem paying when the time comes after all appeals have been exhausted and that one is more than able to pay the Court's interest for the loss of the use of the judgment sum would be cold comfort to the respondents. What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander in that if the appellants may freely use the judgment sum for whatever pursuits be it in new ventures or investment, then should not ADM who has a judgment in its favour for about RM22 million have the same liberty to put to use the same judgment sum and to return it or so much of it when called upon to do so.

[100] It would be clear by now that for every valid fear of the appellants there would be a corresponding equally valid fear of the respondents. It is thus a balancing act; weighing the factors for and against a conditional stay and if so for what portion of the judgment debt pending appeal and on what terms the stay should be.

[101] As the City Neon's 3rd Party Suit's judgment is for about RM 13 million which has been stayed pending appeal, there is thus no need to pay that sum now until the appeal is heard and then depending on the outcome of the appeal, it would be clear then whether and if so how much is to be paid or not at all.

[102] Therefore by a rough ballpark this Court is prepared to allow this sum of RM13 million to be deducted from the sum of RM22 million and to round it up to RM10 million that is required to be paid now with the balance being stayed pending appeal. We have to consider if the whole of the RM10 million is to be paid to ADM who has obtained the judgment sum in its favour or to allow only half of it to be paid to ADM and the other half to be paid to the respondents' solicitors as stakeholders pending the outcome of the appeal.

[103] To have the whole of the balance judgment sum paid to the respondents' solicitors would be a mere cold comfort for even though the money is "secured" in the sense that it is preserved with their solicitors and to be released to ADM once the Court of Appeal confirms the judgment of the High Court, there is still no way to enjoy the fruits of its litigation though it had been successful.

[104] In the circumstances of this case, it would be more fair and reasonable for half of the balance judgment sum to be released to ADM such that it may use it to pay just debts and expenses incurred and to act at all times in the best interest of the company. This Court is not unfamiliar with the fact that whilst the intention of ADM or anyone for that matter in the running of the affairs of a company may initially be above board, sometimes there is a gap between intention and action. We are often confronted with many situations where the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.

[105] This weakness can be addressed with a sanction from the Court. The sum to be released of RM5 million would be against the undertaking of ADM and its two directors Arrasu and Maren given to the Court to refund the said sum or so much of it as may be ordered by the Court of Appeal when the decision is made after the hearing of the pending appeal.

[106] The respondents may object to this on ground that the Court is converting the personal liability of the company ADM to that of its two directors Arrasu and Maren who are also its shareholders in a private limited company. We do not think so. It is plain to all that companies act through the agency of its directors. Between the two of them, they can sign all cheques and indeed to sign the whole company away. We are not saying that that would be done but we are saying that where the financials are not promising and indeed are precarious, the Court must be alert to the danger that the money, and a huge sum at that, would be difficult to recover once it leaves the company. In any event the respondents had not sought leave of the Federal Court to appeal against the terms imposed for a conditional stay with respect to the company ADM's undertaking to the Court and that of its two directors.

[107] Just as the appellants, the respondents must be prepared to put their mouths where the money is and if they say they are honest people of integrity then they should have no objections to a mechanism where if the money has been wrongfully paid out then the directors instrumental for such money being paid out, must be prepared to be personally responsible if the sum paid out is not recoverable. An undertaking by ADM and its two directors given to the Court to so pay when required by the Court would address the concerns of the appellants on the difficulty or impossibility of recovery. There would also be the sanction of contempt of court in the event the undertaking given to the Court is breached. See generally the case of GS Gill Sdn Bhd v. Descente Ltd [2010] 1 MLRA 483 (FC), Tan Poh Lee v. Tan Boon Thien [2022] 2 MLRA 329 (FC) and the case of F Hoffmann-Roche & Co AG & Ors v. Secretary of State for Trade and Industry [1975] AC 295.

[108] As for the other sum of RM5 million, there would be no difficulty of the said sum being repaid to the appellants should the Court of Appeal decide in favour of the appellants or so much of it as it may so decide. The sum is to be held by the respondents' solicitors as stakeholders.

[109] There is nothing like the feel and scent of money that has already been paid to one's solicitors; all ready to be released upon the confirmation by the Court of Appeal of the High Court that had already decided and granted in one's favour. While a digital record of money so paid may not be susceptible to touch and smell, it is the reality of it being there that would outweigh all considerations and promises to pay. Justice would be served if such a reasonable amount be paid to the respondents' solicitors as stakeholders, awaiting the outcome of the appeal, to be kept in an interest earning Fixed Deposit account which interest shall go to the winning parties on appeal or for so much of it.

Decision

[110] We had thus for NU4, granted a conditional stay with respect to the payment of the monetary sum excluding costs of RM500,000.00 awarded (for which costs there shall be no stay) by the High Court on the following terms:

The appellants shall, jointly and severally, pay to the respondent ADM's solicitors the sum of RM10 million within 60 days from the date of the order as follows:

(1) The sum of RM5 million shall be released to the ADM against ADM's undertaking and that of its directors' ie, Arrasu and Maren's undertaking, given to this Court to repay the said sum or so much of it as may be allowed by the Court of Appeal;

(2) The balance of another RM5 million shall be kept by the respondent ADM's solicitors as stakeholders pending the disposal of appeal in the Court of Appeal in a Fixed Deposit interest earning account and the interest shall go to the successful party in the appeal to the Court of Appeal.

[111] The balance of the judgment sum plus interest shall be stayed pending the disposal of the appeals. Needless to say if the above sum of RM10 million is not so paid within 60 days from the date of the order, then there shall be no stay of the execution of the whole of the judgment debt plus interest.

[112] In the event that the undertakings are not forthcoming from ADM and the two directors Arrasu and Maren under condition 1 above, then the said sum of RM5 million shall not be released by the respondent ADM's solicitors to ADM.

[113] We made no order as to costs.

[114] As for NU5, the stay application is with respect to payment of the costs of RM100,000.00 in some related suits heard together for which the appellants have appealed. We see no special circumstances to justify a stay of the payment of costs. Costs have been incurred by the ADM Parties in defending the claims made against them. It is common for costs to follow the event.

[115] The application in NU5 was dismissed with costs of RM10,000 to the respondents, subject to allocatur.