Federal Court, Putrajaya

Azahar Mohamed CJM, Zaleha Yusof, Zabariah Mohd Yusof FCJJ

[Civil Appeal No: 02(f)-76-11-2020W]

21 April 2022

Tort: Defamation - Fair comment - Appellants sued respondent for damages for defamation - Whether respondent could rely on defence of fair comment to defeat appellants' claim - Whether all four elements of fair comment established - Malice, issue of

The 1st appellant was the chairman and director of the 2nd appellant. Both appellants sued the respondent for damages for defamation. The respondent at all material times was the director of strategy of a political party. The appellants claimed that the respondent had defamed them at a press conference by alleging that public funds were used to purchase properties for the 1st appellant's own personal and family gain, contrary to public interest. The High Court decided in favour of the appellants, concluding that the statements made by the respondent ("Impugned Statements") were defamatory of the appellants as they had the effect of lowering the estimation of the appellants in the eyes of the public. According to the High Court, a reasonable reader reading the Impugned Statements would conclude that public funds had been dishonestly misappropriated by the appellants (in order to obtain a personal loan from Public Bank) and that these funds were put at risk by the conduct of the appellants. The High Court held that the defence of fair comment was not available to the respondent as the Impugned Statements were expressed as statements of fact and did not constitute a comment. However, the respondent's appeal to the Court of Appeal was allowed and the High Court's decision was reversed. Hence, the instant appeal by the appellants in which the fundamental issue for determination was whether the respondent could rely on the defence of fair comment to defeat the appellants' claim.

Held (dismissing the appeal):

(1) An ordinary or reasonable man upon reading the Impugned Statements and the way they were expressed, the context in which they were set out and their entire content would regard them as the respondent's comments and inferences made from the facts. To constitute a statement of fact, a statement must be definitive per se about the person(s) where the statement provided a definitive portrayal of a defamed person's character, conduct etc that induced defamatory remarks against him. In the present appeal, looking objectively at how the Impugned Statements were expressed, there were no independent statements which fell within the characterisation laid down by the legal authorities to conclude that the statements were statements of fact per se and not comments or inferences of fact. Hence, the Impugned Statements were the respondent's opinion and inferences made from the facts. (paras 34, 37 & 38)

(2) In relying on the defence of fair comment the respondent must first establish a sufficient substratum of facts from which he drew inferences. Secondly, those facts on which the comment or inferences were made must be truly stated so that the readers could form their own opinion on whether the comment or inferences were well founded. In this instance, the respondent had truly stated the facts existing within his knowledge which he had relied upon to draw inferences and make the comments on the misappropriation of public funds. The breadth of the defence of fair comment only revolved around comments or inferences honestly made based on certain existing substratum of facts that were truly stated. What was required was that the comment had to identify, at least in general terms, the matters on which it was based. This, the respondent had made out to admit the defence of fair comment. After all, that was what defence of fair comment was, as opposed to the defence of justification. The primary reasoning for the creation of the defence of fair comment was the desirability that a person should be entitled to express his view freely about a matter of public interest. (paras 44, 53 & 54)

(3) As indicated earlier, there was a sufficient substratum of facts to warrant the respondent making the Impugned Statements. In this context, it was relevant to note that it was the finding of the High Court that the respondent had an honest belief that his allegations were true and that he was performing a public duty in agitating for greater accountability in respect of public funds. Given all this, the respondent's conclusion that public funds had been misused as leverage for Public Bank's loan was an opinion and inference that a fair-minded person would have honestly made in the circumstances. (paras 59-60)

(4) In light of all the above, all the four elements of fair comment as laid down in Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam v. Goh Chok Tong had been established. Therefore, the respondent could not be liable for damages for defamation. Further, the High Court had made an express finding that the respondent was not motivated by malice in making the defamatory statements. The Court of Appeal did not disturb that finding. In this regard, it was trite law that proof of malice defeated the defence of fair comment because a comment that was made maliciously was not a fair comment. Taking into account that the Impugned Statements were made without malice, the respondent could for that reason resort to the defence of fair comment. (paras 61-62)

Case(s) referred to:

Chen Cheng & Anor v. Central Christian Church and Other Appeals [1999] 1 SLR 94 (folld)

Dato' Sri Dr Mohamad Salleh Ismail & Anor v. Nurul Izzah Anwar & Anor [2021] 2 MLRA 626 (refd)

Dato' Seri Mohammad Nizar Jamaluddin v. Sistem Televisyen Malaysia Berhad & Anor [2014] 3 MLRA 92 (refd)

Hunt v. Star Newspaper Co Ltd [1908] 2 KB 309 (folld)

Joseph and Others v. Spiller and Another [2011] 1 AC 852 (folld)

Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam v. Goh Chok Tong [1989] 1 MLRA 500 (folld)

Kemsley v. Foot & Ors [1952] 1 All ER 501 (folld)

London Artists Ltd v. Littler [1969] 2 QB 375 (refd)

Syarikat Bekalan Air Selangor Sdn Bhd v. Tony Pua Kiam Wee [2015] 6 MLRA 63 (refd)

Synergy Promenade Sdn Bhd v. Datuk Seri Haji Razali Haji Ibrahim [2021] 6 MLRA 602 (refd)

Thomas v. Bradbury, Agnew & Co Ltd [1906] 2 KB 627 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Defamation Act 1957, s 10

Other(s) referred to:

Gatley on Libel and Slander , Sweet and Maxwell, 2008, 11th edn, p 339

Counsel:

For the appellants: Muhammad Shafee Abdullah (Sarah Abishegam & Noor Farhah Mustaffa with him); M/s Shafee & Co

For the respondent: Razlan Hadri (Ranjit Singh, Ng Siau Sun & Tee Yee Man with him); M/s Sun & Michele

JUDGMENT

Azahar Mohamed CJM:

Introduction

[1] The 1st appellant, Datuk Seri Dr Mohamad Salleh bin Ismail was the Chairman And Director of the 2nd appellant, National Feedlot Corporation Sdn Bhd. Both the appellants sued the respondent, Mohd Rafizi Ramli for damages for defamation. The respondent at all material times was the Director of Strategy of a political party. The appellants claimed that the respondent had defamed them at a press conference. The sting, as contended by the appellants, was the allegation by the respondent that public funds were used to purchase properties for the 1st appellant's own personal and family gain contrary to public interest.

[2] The High Court decided in favour of the appellants. The 1st appellant was awarded with the sum of RM150,000 as damages whereas a sum of RM50,000 was awarded to the 2nd appellant, as well as RM100,000 being the costs to be paid to the appellants.

[3] The respondent's appeal to the Court of Appeal was allowed and the High Court's decision was reversed. Hence, in the instant appeal, the main focus is on the defence of fair comment as raised by the respondent.

Background Facts

[4] Beginning from November 2007, the 2nd appellant entered into an Implementation Agreement and a Loan Facility Agreement with the Government of Malaysia ("the Government"). Under the Implementation Agreement, the 2nd appellant was appointed to implement the National Meat Policy 2006, in particular to develop, promote and nurture competency in the farming of beef and cattle for the production of beef and beef products through the National Feedlot Centre Project ("the Project"). The Project was intended to reduce the nation's dependency on imported meat. It was funded by the Government and the land for the project was also provided by the Government. Under the Loan Facility Agreement, the Government provided the 2nd appellant a loan facility of RM250 million to fund the Project. It is important to note that the terms of this agreement contained a covenant that the money disbursed was only to be used for the purpose of the Project.

[5] More significant still, out of the RM250 million, all but a sum of RM71 million was drawn down. That sum of RM71 million that was deposited in a fixed deposit account held by the 2nd appellant in Public Bank became embroiled in the defamation action filed by the appellants against the respondent.

[6] As events unfolded, the Project was subject to audit by the Auditor General. In November 2011, the Auditor General published its report on the status and progress of the Project, which brought to light a number of its failings. This 2011 report as described by the High Court "to be the touch-paper that ignited a conflagration of controversy".

[7] The dispute in this case arose when the respondent convened a press conference on 7 March 2012. So far as the evidence goes, at this press conference, he made a number of allegations against the appellants, the gist of which was that the sum of RM71 million that had been deposited with Public Bank was used as a leverage for personal loans that were used for the purchase eight (8) units of commercial offices in KL Eco City ("the Eight (8) units"), an office block under development in Kuala Lumpur.

[8] The basis of these allegations was founded on certain documents that the respondent claimed to have received anonymously. These documents, some of which, were appended to his press release in redacted form, were print-outs from the records of Public Bank, showing the appellants' customer profile, the companies related to the appellants and of directors of such companies, and the details of the Eight (8) units.

[9] Eventually, the appellants commenced the present action against the respondent. The appellants claimed that the press statements made by the respondent, ordinarily suggest the following imputations that:

(a) The appellants misused public funds for their own personal gain contrary to public interest, in particular the government loan given to the 2nd appellant for the Project.

(b) The 1st appellant had abused his position as the chairman and director of the 2nd appellant to misappropriate the said government loan in order to purchase the Eight (8) units.

(c) The 1st appellant took advantage of his marital status with Datuk Seri Shahrizat Jalil, during her tenure as Member of Parliament of Lembah Pantai to acquire the Eight (8) units.

[10] The appellants maintained that the statements made by the respondent at the press conference and the press release were defamatory of them. They claimed that their names and reputation had been tarnished and caused business losses and opportunities.

[11] The 1st appellant asserted that he and one of his sons had entered into several sale and purchase agreements to purchase the Eight (8) units and for this purpose, had obtained a loan offer from Public Bank. However, the loan facility was cancelled on 4 January 2012 without having been drawn down. Hence, on the date of the press conference convened by the respondent, there was no loan or any loan offer outstanding to the 1st appellant or his son.

Decision Of The High Court

[12] The High Court concluded that the following statements made by the respondent were defamatory of the appellants as they had the effect of lowering the estimation of the appellants in the eyes of the public ("the Impugned Statement"):

"1. Clearly, this proves how the public funds which were given to NFC to develop the project has been misappropriated to be used as a guarantee to obtain personal loans and to be spent by purchasing properties in their personal names.

2. The method of misappropriation of public funds to obtain a personal loan such as this is against the mandate which was given to NFC to develop a project which is of national interest."

[13] According to the High Court, a reasonable reader reading the Impugned Statement would conclude that public funds had been dishonestly misappropriated by the appellants and that these funds were put at risk by the conduct of the appellants.

[14] Having established that the Impugned Statement made by the respondent was defamatory, the High Court next considered whether his pleaded defence can be sustained. The High Court held that the defence of fair comment was not available to the respondent as the statements made by the respondent were expressed as statement of facts and did not constitute a comment. The statements were based on the documents which the respondent obtained. However, there was nothing in the documents that suggested that the deposit by the 2nd appellant had been used either as a leverage or as a security or collateral for the grant of any loan. The basic facts available to the respondent did not support the inference that he had drawn from those facts.

Decision Of The Court Of Appeal

[15] At the Court of Appeal hearing, quite unexpectedly the Court brought up the issue of s 10 of the Defamation Act 1957 (Act 286) ("DA 1957") which concerns the apology in mitigation of damages and linked it with the fact that the appellants' letter of demand did not contain any mention of the fact that the loan had been withdrawn. The issue of the letter of demand and s 10 of the DA 1957 had not been raised at all in the High Court by either party, nor in the pleadings of parties, nor in the memorandum of appeal at the Court of Appeal and submissions by both parties. However, the Court of Appeal proceeded to deal with the appeal as though the letter of demand and s 10 of the DA 1957 was the entire answer to the case in favour of the respondent. Consequently, the respondent's appeal to the Court of Appeal was allowed and the High Court's decision was reversed.

The Leave Questions

[16] It was agreed by both parties at the hearing of the appellants' application for leave to appeal to this Court that several of the grounds of the decision of the Court of Appeal were outside the pleaded case of both parties. Section 10 of the DA 1957 was not pleaded or raised by either party in the High Court or the Court of Appeal. This approach taken by the Court of Appeal cannot be right. The respondent therefore did not object to the application for leave, and leave to appeal was given with a condition that parties be allowed to ventilate the defence of fair comment before this Court.

[17] For completeness, this Court granted the appellants leave to appeal on the following questions of laws:

Question 1: Whether in a defamation action, a letter before action is a prerequisite to the statement of claim?

Question 2: Is there a co-relationship between s 10 Defamation Act 1957 (Act 286) and a letter before action in a defamation claim?

Question 4: Does the plaintiff in a defamation action, either in his letter before action or in his statement of claim, owe a duty to the defendant to elaborate the particulars of the untruthfulness of the impugned defamatory statement apart from unequivocally stating that the defamatory impugned statement simply enabled the defendant to consider seeking the benefit of s 10 of the Defamation Act 1957 (Act 286)?

Question 6 (a): Can the very same aspect of "malice" which defeated the defendant's defence of qualified privilege survive the defence of fair comment in the same course of action?

Question 6 (b): Does "malice" have different or like species relevant to the distinct defences of qualified privilege and fair comment?

[18] As Questions 1, 2 and 4 have no bearing on the outcome of this appeal, parties have agreed to focus their submissions on Question 6(a) and (b). Both parties also agreed that the present appeal really turns on the question whether the respondent had proved the defence of fair comment.

[19] Both sides have submitted that this Court should answer Question 6(a) and (b) in the negative. However, it is made clear by learned counsel for the respondent particularly, that even though the questions should be answered in the negative, such conclusion arrived from different reasoning as opposed to the appellants'.

[20] The differences of the reasoning were premised on two (2) stand points. For the appellants, the Impugned Statement made by the respondent on 7 March 2012 was not a fair comment, instead, a statement of facts. Hence, since it was a statement of facts, it had to be proven and established to be true. The appellants' learned counsel argued that the Impugned Statement particularly made at the time of publication was untrue since there was no evidence that the loan granted by Public Bank was drawn down to purchase the Eight (8) units. This is fortified by the fact that the loan facility was cancelled on 4 January 2012 via a letter by Public Bank. Consequently, the falsity of such statements renders the Impugned Statement defamatory.

[21] The respondent's stance was that the Impugned Statement was a comment and expression of opinion honestly held by the respondent because in the context of the entire statements, it was reasonable to infer this as instances of misuse of public funds by the appellants. According to respondent's learned counsel, the details exposed by the respondent via series of attachments of A to E during the press statement, were facts upon which an inference was then drawn to reach a reasonable conclusion that public funds had been misappropriated. As a result, the defence of fair comment was available to shield the respondent against the appellants' defamation action.

Findings And Analysis

[22] What is important to note in this appeal is that the correctness of the High Court's ruling that the Impugned Statement made by the respondent was defamatory to the respondent is not disputed. Before us, the respondent's main contention is that the High Court erred in holding that the defence of fair comment did not avail him.

[23] For the lack of proper reasoning in relation to the defence of fair comment in the Court of Appeal, ultimately, the focal point in this present appeal in reality, is the findings of the High Court on this issue. Flowing from the arguments raised by both sides, the fundamental issue for our determination is whether the respondent could rely on the defence of fair comment to defeat the appellants' claim.

[24] The High Court correctly directed itself in law that in order to succeed in his defence of fair comment, the respondent will need to establish the four (4) elements in Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam v. Goh Chok Tong [1989] 1 MLRA 500 PC ("Joshua Benjamin"):

i. The words complained of are comments, although they may consist or include inferences of fact;

ii. The comment is on a matter of public interest;

iii. The comment is based on facts'; and

iv. The comment is one which a fair-minded person can honestly make on the facts proved.

[25] The High Court found that the Impugned Statement concerns matters of public interest, to which, I agree. Both the parties did not address the Court on this issue. Suffice for me to say that the matter was such as to affect the people at large, so that they may be legitimately interested in, or concerned at what was going on (see London Artists Ltd v. Littler (1969) 2 QB 375).

[26] The High Court further held that the respondent failed to establish the other three (3) elements. I will now deal in turn each of these three (3) elements.

Words Must Be In The Form Of Comment/Inferences

[27] First, whether the Impugned Statement made by the respondent is a comment? It is the appellants' contention that the Impugned Statement was a statement of fact and did not constitute a comment or inferences of facts. The basis of his argument is simply contingent upon the findings of the High Court's grounds of judgment:

"[32] In my judgment, the statement made by En Rafizi were couched as statements of fact and did not constitute comment. The statement, in gist, asserted that (among others):

(a) public funds had been misused for the personal benefit of Datuk Seri Salleh's family; and

(b) public funds had been misappropriated by Datuk Seri Salleh.

[33] It may be argued that the statement made by En Rafizi were inferences of fact, which may constitute commentary according to Gatley. If so, it falls to be determined whether the facts from which the conclusions of En Rafizi were inferred had been sufficiently established."

[28] In supporting this stance, learned counsel for the appellants relied on the case of Hunt v. Star Newspaper Co Ltd [1908] 2 KB 309; CA pp 319-320 ("Hunt") cited in Kemsley v. Foot & Ors [1952] 1 All ER 501; HL ("Kemsley").

[29] Learned counsel for the respondent also relied on Kemsley (supra) to support his contentions that the Impugned Statement made by the respondent were comments and inferences of facts. Further, he also pointed out during the course of his oral submissions that in finding the Impugned Statement was a statement of facts, the High Court had overlooked the language of the Impugned Statement which made it clear that it was the respondent's opinion based on express references to admitted facts.

[30] It is important as the first task to ascertain whether the Impugned Statement is a statement of fact or is it the respondent's opinion and inferences made from the facts. The necessity to decide this is a fundamental requirement in order to determine whether the defence of fair comment is available to the respondent. This is because "if the imputation is one of fact, the defence must be justification or privilege" (see Gatley on Libel and Slander, 11th edn, Sweet and Maxwell, 2008, p 339 ("Gatley, 11th edn")) and therefore the respondent could not rely on the defence of fair comment.

[31] In addressing what constitutes fact or comment, Lord Ackner in Joshua Benjamin (supra) stated as follows at p 503:

"As regards (ii) above, it was not contested that the comment, if it was a comment and not an assertion of fact, was on a matter of public interest. Their Lordships accordingly deal seriatim with elements (i), (iii) and (iv).

(i) Were the words complained of comment?

Lord Hooson did not dissent from the following statement to be found in para 697 of the current (8th edn) of Gatley on Libel and Slander:

Comment is a statement of opinion on facts. It is comment to say that a certain act which a man has done is disgraceful or dishonourable; it is an allegation of fact to say he did the act so criticized... while a comment is usually a statement of opinion as to merits or demerits of conduct, an inference of fact may also be a comment. There are, in the cases, no clear definitions of what is comment. If a statement appears to be one of opinion or conclusion, it is capable of being comment.

Of course, if a statement is capable of being comment, whether or not it is a comment or a statement of fact, must be a matter for the jury properly directed or, in this case where trial was by judge alone, for the judge, properly directing himself, to decide.

At the press conference, after stating that the appellant had spoken at the inaugural, the respondent said that the appellant 'left the hall, and when he left the hall 200 participants left with him'. These were clearly statements of fact. He then said:

I believe the exodus was engineered. I don't think it was a spontaneous exodus. If it was, it did not speak well for the SDP. It shows that the crowd, the limited crowd still looks toward Mr Jeyaretnam, for the time being as a leader of the opposition. But I am inclined to believe that the exodus was contrived by the leader of the Workers' Parly to show who is boss at this stage. And surely Mr Chiam cannot take that trick lightly.

[Emphasis Added]

In their Lordships' judgment it was clearly open to the judge to take the view that the observations following the statement of facts were expressions of opinion or conclusions or inferences drawn from those facts and therefore capable of being comment. This being so, he was fully entitled to decide that these observations were 'a comment and not a bare or naked statement of facts. It contained the defendant's belief for his conclusions based on or drawn from certain facts'."

[Emphasis Added]

[32] In other words, a comment, opinion or inferences of fact are different from a statement of fact. However, all the former must be based on facts. It is therefore vital to refer to the Impugned Statement and assessed whether it is a statement of fact or the respondent's opinion or inferences made from facts. It is very important now to look at closely the whole of the statements (without its attachments A to E) made by the respondent (the Impugned Statement is highlighted):

"Bukti Bagaimana Dana Awam Untuk Projek Fidlot Digunakan Sebagai 'Jaminan Pinjaman Peribadi Untuk Membeli 8 Unit Hartanah Mewah Di KL Eco City, Bangsar.

Seperti yang dijanjikan, KEADILAN hari ini tampil dengan bukti kukuh bagaimana dana awam yang disalurkan kepada NFC untuk projek berimpak tinggi dan berkepentingan awam telah disalahgunakan bagi tujuan peribadi keluarga Dato' Seri Shahrizat Jalil yang memiliki NFC.

Modus operandi yang digunakan adalah mudah - sejumlah besar dana tersebut didepositkan ke dalam bank-bank tertentu. Keluarga Dato' Seri Shahrizat kemudiannya membuat pinjaman pembiayaan untuk membeli pelbagai hartanah mewah di bawah nama mereka walaupun secara peribadinya, mereka tidak mempunyai simpanan yang kukuh di bank tersebut.

Semakan dengan sebuah bank tempatan mengesahkan fakta-fakta berikut setakat 16 Februari 2012 (yang disokong dengan dokumen carian kredit rasmi bank tersebut yang disertakan bersama):

1. Lampiran A mengesahkan bahawa National Feedlot Corporation Sdn Bhd mempunyai simpanan deposit berjumlah RM71,395,617 dalam akaun 01181839801 dan RM90,972 dalam akaun 03984628723 di sebuah bank tempatan.

2. Lampiran B mengesahkan bahawa syarikat milik penuh keluarga Dato' Seri Shahrizat Jalil iaitu National Meat & Livestock Corporation Sdn Bhd mempunyai deposit berjumlah RM1,872,254 di akaun bernombor 03147802316 di bank tersebut.

3. Lampiran C mengesahkan bahawa syarikat milik penuh keluarga Dato' Seri Shahrizat Jalil iaitu Agroscience Industries Sdn Bhd mendapat kemudahan pembiayaan berbaki RM197,338 melalui pinjaman bernombor 02050032605, walaupun syarikat itu hanya mempunyai simpanan berjumlah RM927 di bank tersebut.

4. Lampiran D mengesahkan bahawa Dato' Seri Salleh Ismail mendapat pinjaman peribadi berbaki RM4,391,240 untuk membiayai secara bersama pembelian hartanah melalui pinjaman bernombor 02062369427 dan menjadi penjamin kepada satu lagi pinjaman hartanah bernombor 02073919403 berbaki RM663,743 walaupun beliau secara peribadi hanya mempunyai simpanan RM421 di bank tersebut.

5. Secara jelas, ini membuktikan bagaimana dana awam yang diberikan kepada NFC untuk mengusahakan proiek fidlot telah diselewengkan untuk dijadikan jaminan untuk mendapatkan pinjaman peribadi dan dibelanjakan dengan membeli hartanah-hartanah di atas nama peribadi mereka.?

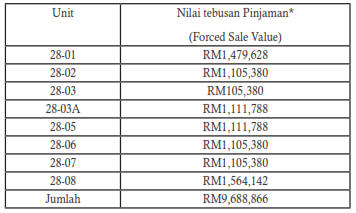

Semakan KEADILAN menunjukkan bahawa pinjaman peribadi Dato' Seri Salleh Ismail dari bank tersebut telah digunakan untuk membeli 8-unit hartanah di KL Eco City Sdn Bhd seperti berikut (bukti pembelian dan rekod pinjaman dalam Lampiran E):

Nilai tebusan pinjaman adalah anggaran harga hartanah yang dapat diperolehi semasa lelongan dan lebih rendah dari harga pasaran. Berdasarkan harga pasaran semasa unit komersil di KL ECO City iaitu RM1,000 hingga RM1,100 setiap kaki persegi, KEADILAN menganggarkan harga pasaran semasa unit-unit ini boleh mencecah RM12 juta.

Kaedah menyalahgunakan dana awam untuk mendapatkan pinjaman peribadi seperti ini adalah menyalahi mandat yang diberikan kepada NFC untuk membangunkan projek berkepentingan nasional.

Keadilan juga melahirkan rasa bimbang melihat rekod pembayaran pinjam yang buruk; termasuklah tidak membayar bayaran pinjaman dalam bulan Julai dan Ogos 2011 selama dua bulan berturut-turut. Dalam bulan Disember 2011, perkara ini berulang kembali.

Memandangkan simpanan tetap NFC sebanyak RM71.4 juta berkait rapat dengan pembelian harta-harta peribadi ini, pengurusan NFC dan Dato' Seri Shahrizat Jalil, sebagai mewakili keluarganya, perlu memberi jaminan bahawa sebarang masalah pembayaran membabitkan pinjaman peribadi mereka tidak akan memberi apa-apa kesan kepada dana awam yang disimpan di bank yang sama."

(Attachments A to E are the print-out of Public Bank's record of the appellant's bank accounts.)

[33] As correctly submitted by learned counsel for the respondent, the Impugned Statement must be read and considered in the context of the entire statements made by the respondent and not in isolation (see Synergy Promenade Sdn Bhd v. Datuk Seri Haji Razali Haji Ibrahim [2021] 6 MLRA 602 CA paras [28]-[29]).

[34] In my view, an ordinary or reasonable man upon reading the Impugned Statement and the way it was expressed, the context in which it was set out and the content of the entire statement would regard them as the respondent's comments and inferences made from the facts. The facts relied upon by the respondent will be discussed in a greater detail later in this judgment. A key point to note is that the Impugned Statement did not single-out an action nor independently alleging a particular conduct of the appellants per se . The more closely one looked at the entire statements, the more apparent it became that based on a series of facts namely the attachments A to E, inferences are derived upon "kaedah" and "modus operandi" that there is misappropriation of public funds which needed to be accounted for. Materially, as argued by learned counsel for the respondent, the language of the statements - "tampil dengan bukti kukuh" and "Secara jelas... ini membuktikan bagaimana dana awam... telah diselewengkan untuk dijadikan jaminan untuk mendapatkan pinjaman peribadi" clearly identified the facts relied on by the respondent to state his comment and inferences, which enable the readers to come to their own conclusions whether the respondent's opinion was correct.

[35] Understanding the Impugned Statement in this fashion is in accordance with how Joshua Benjamin (supra) distinguished between a statement of fact or comment. Further, Gatley (supra) is instructive on examining words of an impugned statement. Gatley (supra) at s 12.6 p 339 states this:

"Though "comment" is often equated with "opinion", this is oversimplification. More accurately it has been said that the sense of comment is "something which is or can reasonably be inferred to be a deduction, inference, conclusion, criticism, remark, observation, etc." The first step is to determine the meaning of what the defendant has said in its context and for this purpose the law adheres to the normal rule that words are treated as having a single meaning. It is possible to distinguish at least three situations.

(1) A statement may be a "pure" statement of evaluative opinion which represents the writer's view on something which cannot be meaningfully verified - "I do not think Jones are attractive".

(2) A statement which is potentially one of fact or opinion according to the context - "Jones behaves disgracefully".

(3) As statement which is only capable of being regarded as one of fact and in no sense one of opinion - "Jones took a bribe"

- but which may be an inference drawn by writer from other facts.

Fair comment clearly applies to the first situation; it applies to the second situation if, in the context, is to be understood as an expression of opinion (eg because the writer has just described some controversial act of Jones); the third situation involves greater subtlety (or uncertainty)."

[36] Another case that is instructive is the case of Chen Cheng & Anor v. Central Christian Church and Other Appeals [1999] 1 SLR 94; SGCA ("Chen Cheng ") which discussed in length on the distinction between facts and comment. LP Thean LA made some observations on cases in other jurisdictions and concluded with the following observations:

" Distinction between fact and comment

[34] The difficulty here is to distinguish between an assertion of fact and a comment. In dealing with this issue the learned judge held summarily (at 99) that a statement that a group is a cult is essentially a comment. That, with respect, is an over-simplification. Such a statement may be a statement of fact or a comment, depending on the manner in which the statement is made and the context in which it is made, and in determining this issue the whole of the article or passage in question has to be read and considered. Gatley on Libel and Slander (9th Ed) in 12.6-12.10 provides various propositions as guides in ascertaining whether a statement is one of fact or comment, but all of them, though helpful, are by no means decisive or conclusive. The learned editors say:

[12.6] The distinction. It has been said that the sense of comment is 'something which is or can reasonably be inferred to be a deduction, inference, conclusion, criticism, remark, observation, etc'.

[12.7] Fact and comment: the significance of supporting facts If a defamatory allegation is to be defended as fair comment it must be recognisable by the ordinary, reasonable reader as comment and the key to this is whether it is supported by facts, stated or indicated, upon which, as comment, it may be based

[12.8] Construction. While some indication of the supporting facts is necessary the ultimate question is how the words would strike the ordinary, reasonable reader and it is unlikely that any attempt to formulate general principles of construction will be much help

[12.9] Context. In order to determine whether the words are fact or comment the judge or jury is confined to the context of the publication in respect of which the action is brought What is necessary is that language must be used which conveys to the reader that the defendant is commenting on what the writer of the article has said

[12.10] Inferences of fact as comment. It is clear that a comment may consist of an inference or deduction of fact; that is, an author can assert, as his comment on facts stated or referred to in what he publishes, some other fact the existence of which he infers or deduces from those facts. Thus, if the author sets out facts in relation to the plaintiff 's conduct and states that his inference from those facts is that the plaintiff must have been bribed so to act, his statement will fall within the defence, though it is possible in this situation that mere honesty on his part will not suffice.

[35] At the end of the day much depends on how the defamatory statement is expressed, the context in which it is set out and the content of the entire article or passage in question. One should adopt a common-sense approach and consider how the statement would strike the ordinary reasonable reader, ie whether it would be recognizable by the ordinary reader as a comment or a statement of fact.

[Emphasis Added]

[37] Joshua Benjamin (supra), Gatley , 11th edn (supra) and Chen Cheng (supra) are authorities to support the proposition that to constitute statement of facts, a statement must be definitive per se about the person(s) where the statement provides definitive portrayal of a defamed person's character, conduct or etc. that induces defamatory remarks against him.

[38] Reverting to the present appeal, in my opinion, looking objectively on how the Impugned Statement was expressed, there is no independent statements which falls within the characterization laid by the legal authorities to conclude that the statements are statements of fact per se and not comment or inferences of fact. In my opinion, the Impugned Statement was the respondent's opinion and inferences made from the facts.

Opinion/Inferences Must Be Based On True Substratum Of Facts

[39] Which then brings me to the more delicate and difficult issue whether the Impugned Statement made by the respondent was comment or inferences based on facts that are required by the test laid down by Joshua Benjamin (supra). This is a crucial point which I must look closely.

[40] It is the nub of the appellants' learned counsel's argument that other than the Impugned Statement made was worded as statement of fact and therefore did not constitute a comment, the Impugned Statement was also unsupported and untrue. He particularly referred to the fact that the Public Bank loan granted to the 1st appellant had been withdrawn by the time the Impugned Statement was made. He argued that there were no basic facts to infer that public fund was used as a leverage or a collateral for loan to purchase the Eight (8) units. This contention is substantially based on the following reasoning of the High Court:

"Where the comments based on facts that En Rafizi established to be true?

[35] In the present case, the assertion by En Rafizi that public funds have been misappropriated by Datuk Seri Salleh was premised on the documents that En Rafizi had obtained. On the face of these documents, they showed (among others) that the second plaintiff, National Feedlot Corp Sdn Bhd, had deposited an amount of approximately RM71.4m (for ease of reference, all figures in this judgment are rounded to three significant figures) with a bank (subsequently identified as Public Bank Bhd) and that eight properties were recorded in the collateral system of the bank. The cumulative forced sale value of these properties was approximately RM9.69m. These properties were identified as the eight office units in the KL Eco City project.

[36] In my judgment, the documents by themselves cannot justify the inference that has been drawn by En Rafizi. There was nothing in the documents themselves that suggested that the deposit by the second plaintiff had been used either as leverage or as security or collateral for the grant of any loan. More importantly, in order to be able to avail himself of the defence of fair comment, it would have been necessary for En Rafizi to establish the basic fact that no loan would have been granted but for the fact of the deposit of the RM71.4m by the second plaintiff. By his own admission, En Rafizi did not have any knowledge regarding Datuk Seri Salleh's other sources of income. Hence, he was not able to say whether or not the bank would have granted the loan solely on the credit standing of Datuk Seri Salleh.

[37] In other words, the basic facts then available to En Rafizi do not in my view support the inference that he had drawn from those facts."

[41] Learned counsel for the appellants argued that it is important to ascertain the veracity of the basic facts. He added that even if the respondent succeeded in arguing that the Impugned Statement was in point of fact the respondent's opinions and inference made from the facts, that basic facts must be established to be true. To support this point, Joshua Benjamin (supra) again was relied on by learned counsel. In this context, he quoted passages at pp 503-504 as follows:

"It is of course well established that a writer may not suggest or invent facts and then comment upon them, on the assumption that they are true. If the facts upon which the comment purports to be made do not exist, the defence of fair comment must fail. The commentator must get his basic facts right.

The basic facts are those which go the pith and substance of the matter: see Cunningham-Howie v. Dimbleby [1951] 1 KB 360 364. They are the facts on which the comments are based or from which the inferences are drawn - as distinct from the comments or inferences themselves. The commentator need not set out in his original article all the basic facts: see Kemsley v. Foot [1952] AC 345 but he must get them right and be ready to prove them to be true;

(per Lord Denning MR in London Artists Ltd v. Littler [1969] 2 QB 375.)"

[42] The appellants' learned counsel also referred to the case of Hunt (supra) which was cited in Kemsley (supra) to establish the requirement that the respondent must truly state all the basic facts in making an inference of fact. He also argued that if facts and comments are intermingled, it has to be deemed as statement of facts. The specific passage relied in Hunt (supra) are as follows:

"If the facts are stated separately and the comment appears as an Inference drawn from those facts, any Injustice that It might do will be to some extent negatived by the reader seeing the grounds upon which the unfavourable inference is based. But if fact and comment be intermingled so that it is not reasonably clear what portion purports to be inference, he will naturally suppose that the injurious statements are based on adequate grounds known to the writer though not necessarily set out by him. In the one case the insufficiency of the facts to support the inference will lead fair- minded men to reject the inference. In the other case it merely points to the existence of extrinsic facts which the writer considers to warrant the language he uses ... In the next place, in order to give room for the plea of fair comment the facts must be truly stated. If the facts upon which the comment purports to be made do not exist the foundation of the plea fails. This has been so frequently laid down authoritatively that I do not need to dwell further upon it: see, for instance, the direction given by Kennedy J. to the jury in Joynt v. Cycle Trade Publishing Co, 49 which has been frequently approved of by the courts. Finally, comment must not convey imputations of an evil sort except so far as the facts truly stated warrant the imputation."

[Emphasis Added]

[43] Learned counsel for the respondent argued that the true ratio decidendi of Kemsley (supra) states that it is sufficient for the facts relied truly stated in the libel in making an inference of fact. He relied on another passage in Kemsley (supra) to establish about the manner relevant in distinguishing a statement of facts or a comment. The passage at pp 356-357 stated as follows:

"The question, therefore, in all cases is whether there is a sufficient substratum of fact stated or indicated in the words which are the subject-matter of the action, and I find my view well expressed in the remarks contained in Odgers on Libel and Slander (6th ed 1929), at p 166. "Sometimes, however," he says, "it is difficult to distinguish an allegation of fact from an expression of opinion. It often depends on what is stated in the rest of the article. If the defendant accurately states what some public man has really done, and then asserts that 'such conduct is disgraceful,' this is merely the expression of his opinion, his comment on the plaintiff's conduct. So, if without setting it out, he identifies the conduct on which he comments by a clear reference. In either case, the defendant enables his readers to judge for themselves how far his opinion is well founded; and, therefore, what would otherwise have been an allegation of fact becomes merely a comment. But if he asserts that the plaintiff has been guilty of disgraceful conduct, and does not state what that conduct was, this is an allegation of fact for which there is no defence but privilege or truth. The same considerations apply where a defendant has drawn from certain facts an inference derogatory to the plaintiff. If he states the bare inference without the facts on which it is based, such inference will be treated as an allegation of fact. But if he sets out the facts correctly, and then gives his inference, stating it as his inference from those facts, such inference will, as a rule, be deemed a comment. But even in this case the writer must be careful to state the inference as an inference, and not to assert it as a new and independent fact; otherwise, his inference will become something more than a comment, and he may be driven to justify it as an allegation of fact."

[Emphasis Added]

[44] In my view, the key principles that may be extracted from the above discussion are, first, in relying on the defence of fair comment the respondent must establish a sufficient substratum of facts upon which he draws inferences. Secondly, those facts on which the comment or inferences were made must be truly stated so that the readers may form their own opinion whether the comment or inferences were well founded. This is consistent with Joshua Benjamin (supra) that the comments made on inference of fact must be true facts. Lord Oakley in a supporting judgment in Kemsley (supra) explained what are facts truly stated at pp 360-361 as follows:

"The forms in which a comment on a matter of public importance may be framed are almost infinitely various and, in my opinion, it is unnecessary that all the facts on which the comment is based should be stated in the libel in order to admit the defence of fair comment. It is not, in my opinion, a matter of importance that the reader should be able to see exactly the grounds of the comment. It is sufficient if the subject which ex hypothesi is of public importance is sufficiently and not incorrectly or untruthfully stated. A comment based on facts untruly stated cannot be fair. What is meant in cases in which it has been said comment to be fair must be on facts truly stated is, I think, that the facts so far as they are stated in the libel must not be untruly stated."

[Emphasis Added]

[45] This essentially means, to constitute a sufficient substratum of fact it is not required that all the facts on which the respondent's comments or inferences were based on should be stated in order to admit the defence of fair comment. This makes sense as the defence of fair comment may be contrasted with the defence of justification that requires every defamatory allegations made to be true or are substantially true (see Dato' Seri Mohammad Nizar Jamaluddin v. Sistem Televisyen Malaysia Berhad & Anor [2014] 3 MLRA 92 CA ("Dato' Seri Mohammad Nizar"), Syarikat Bekalan Air Selangor Sdn Bhd v. Tony Pua Kiam Wee [2015] 6 MLRA 63 FC and Dato' Sri Dr Mohamad Salleh Ismail & Anor v. Nurul Izzah Anwar & Anor [2021] 2 MLRA 626 FC). However, the substratum of facts relied upon by the respondent in making his comments must be true and existing. It is as what Joshua Benjamin (supra) stated, that "a writer may not suggest or invent facts and then comment upon them, on the assumption that they are true". In other words, a plea of fair comment is not available to the respondent if the respondent invented or created the facts he intended to rely on.

[46] In the present case, the attachments A to E to the whole statements made by the respondent are the print-outs of Public Bank's record of the appellants' bank accounts. The attachments and their references in the statements set out the following basic facts:

a. The 2nd appellant's fixed deposit of RM71,393,617;

b. National Meat and Livestock Corporation Sdn Berhad Sdn (a company controlled by the 1st appellant's family) fixed deposit of RM1,872,254;

Bank loan of RM197,338 to Agroscience Industries Sdn Bhd (a company controlled by the 1st appellant's family), and its deposit account has a credit of RM927;

d. The 1st appellant was given a loan of RM4,391,240 and he stood as a guarantor for a loan of RM663,743 when his deposit account with the bank only had RM421;

e. Loan obtained by the 1st appellant to finance purchase of Eight (8) units of real property from KL Eco City Sdn Bhd with a total forced sale value of RM9,688,866.

[47] It is material to point out that the truth of the facts contained in these documents are not disputed. It must be said, however, that the loan was cancelled without having been drawn down. However, this information that only the appellants could have known was not even mentioned in the notice of demand dated 28 June 2012, which was sent by the appellants to the respondent. It is also noteworthy as observed by the High Court that the 2nd appellant had deposited an amount of RM71,393,617 with Public Bank and that the Eight (8) units were recorded in the collateral system of the bank and the cumulative forced sale value of these properties was approximately RM9.69m.

[48] The High Court, however, found that the inferences made by the respondent were not supported by facts. The High Court particularly referred to the fact that the loan granted by Public Bank to the 1st appellant had been withdrawn by the time the Impugned Statement was made by the respondent, and concluded that the facts relied on by the respondent was inaccurate. But in so deciding, in my view, the High Court failed to appreciate that the withdrawal of the loan confirmed that such loan had been granted to the 1st appellant and his son despite their lack of solid savings with Public Bank. And this, tellingly, coincided with the 2nd appellant's enormous fixed deposit in the sum of RM71,393,617 at the same time with the said bank. It is often the case that financial standing must certainly be an important factor for any customers seeking loans from any banks. It is therefore unsurprised that a reader reading the substratum of facts at para [46] of this Judgment will draw inferences that the RM71,393,617 deposit played a part in Public Bank's initial loan offer to the 1st appellant for the purchase of the Eight (8) units.

[49] In my opinion, having regards to the circumstances prevailing at the material times when the press conference was held, those basic facts at para [46] of this Judgment constitute sufficient substratum of facts, which are the subject matter of the appellants' defamation against the respondent. Based on these substratum of facts, the respondent made the following conclusions in the Impugned Statement, which in my view are his opinion and inferences from the facts referred to earlier:

a. Attachments A to E are "solid proofs" (bukti kukuh) that the funds for the project were misused;

b. the "modus operandi" adopted by the 2nd appellant and his family was depositing huge amount of public fund with a bank, and then take out loan to finance purchase of luxury property in their personal name, even though they personally do not have solid savings in their bank accounts;

c. the attachments show that the Project's funds were used as leverage ("jaminan") for the Public Bank loan - "secara jelas, ini membuktikan ...";

d. such action ("kaedah menyalahgunakan dana awam... seperti ini") is a breach of the mandate given to the 2nd appellant.

[50] In the most recent UK case of Joseph and Others v. Spiller and Another (Associated Newspaper Ltd and Others Intervening) [2011] 1 AC 852; UKSC ("Joseph "), the law of defence of fair comment in defamation had been extensively spelled out. Joseph (supra) had laid down the history and development of the law of defence of fair comment in great detail including deliberating the principles laid down in Kemsley (supra) and Hunt (supra).

[51] Joseph (supra) is a case of importance as it is a case to decide (i) whether the defendant can rely in support of their plea on fair comment on matters to which they made no reference in their comment and (ii) whether the matters to which the defendants did refer in their comment capable of sustaining a defence of fair comment. It also rationalises and summarises the latest requirement of the law of defence of fair comment as follows:

"98. ... There is no case in which a defence of fair comment has failed on the ground that the comment did not identify the subject matter on which it was based with sufficient particularity to enable the reader to form his own view as to its validity. For these reasons, where adverse comment is made generally or generically on matters that are in the public domain I do not consider that it is a prerequisite of the defence of fair comment that the readers should be in a position to evaluate the comment for themselves.

99. What of a case where the subject matter of the comment is not within the public domain, but is known only to the commentator or to a small circle of which he is one? Today the Internet has made it possible for the man in the street to make public comment about others in a manner that did not exist when the principles of the law of fair comment were developed, and millions take advantage of that opportunity. Where the comments that they make are derogatory it will often be impossible for other readers to evaluate them without detailed information about the facts that have given rise to the comments. Frequently these will not be set out. If Lord Nicholls's fourth proposition is to apply the defence of fair comment will be robbed of much of its efficacy.

100. ...

101. There are a number of reasons why the subject matter of the comment must be identified by the comment, at least in general terms The underlying justification for the creation of the fair comment exception was the desirability that a person should be entitled to express his view freely about a matter of public interest. That remains a justification for the defence, albeit that the concept of public interest has been greatly widened. If the subject matter of the comment is not apparent from the comment this justification for the defence will be lacking. The defamatory comment will be wholly unfocused.

102. It is a requirement of the defence that it should be based on facts that are true. This requirement is better enforced if the comment has to identify, at least in general terms, the matters on which it is based. The same is true of the requirement that the defendant's comment should be honestly founded on facts that are true.

103. More fundamentally, even if it is not practicable to require that those reading criticism should be able to evaluate the criticism, it may be thought desirable that the commentator should be required to identify at least the general nature of the facts that have led him to make the criticism. If he states that a barrister is "a disgrace to his profession" he should make it clear whether this is because he does not deal honestly with the court, or does not read his papers thoroughly, or refuses to accept legally aided work, or is constantly late for court, or wears dirty collars and bands.

104. Such considerations are, I believe, what Mr Caldecott had in mind when submitting that a defendant's comments must have identified the subject matter of his criticism if he is to be able to advance a defence of fair comment. If so, it is a submission that I would endorse. I do not consider that Lord Nicholls was correct to require that the comment must identify the matters on which it is based with sufficient particularity to enable the reader to judge for himself whether it was well founded. The comment must, however, identify at least in general terms what it is that has led the commentator to make the comment, so that the reader can understand what the comment is about and the commentator can, if challenged, explain by giving particulars of the subject matter of his comment why he expressed the views that he did. A fair balance must be struck between allowing a critic the freedom to express himself as he will and requiring him to identify to his readers why it is that he is making the criticism.

Conclusion

105. For the reasons that I have given I would endorse Lord Nicholls's summary of the elements of fair comment that I have set out at para 3 above, save that I would rewrite the fourth proposition: " Next the comment must explicitly or implicitly indicate, at least in general terms, the facts on which it is based."

[Emphasis Added]

[52] By parity of reasoning, it is unnecessary in the present case to prove that there is a loan existing at the time the Impugned Statement was made, or to go over and beyond to prove as what the High Court reasoned, that "no loan would have been granted but for the fact of the deposit of the RM71.4m by the 2nd plaintiff ". It is sufficient as Joseph (supra) held that based on the facts that are stated in general terms, as we have seen in para [46] of this Judgment, the respondent made the impugned opinion and inferences.

[53] There is much force in the argument of learned counsel that the respondent had truly stated the facts existing within his knowledge which he had relied on to draw inferences and make the comments on the misappropriation of public funds. This argument found support in law per Hunt (supra), Kemsley (supra) and ultimately Joseph (supra).

[54] The point that I want to make can now be concluded as follows. The breadth of the defence of fair comment only revolves around comments or inferences honestly made based on certain existing substratum of facts that are truly stated. What is required is that the comment has to identify, at least in general terms, the matters on which it is based. This, in my view, the respondent had made out to admit the defence of fair comment. After all, that is what defence of fair comment is, as opposed to the defence of justification. The primary reasoning for the creation of the defence of fair comment is the desirability that a person should be entitled to express his view freely about a matter of public interest.

Comment/Inferences Must Be Fair

[55] Finally, I will deal with the issue whether the comment and inferences made by the respondent are one which a fair-minded person can honestly make.

[56] In Joshua Benjamin (supra), the Privy Council confirmed the test of 'fair' comment at p 505:

"The trial judge quoted very aptly from the direction given to the jury by Diplock J (as he then was) in Silkin v. Beaverbrook Newspapers Ltd at p 749:

The matter which you have to decide and I emphasise this again, because it is so important, is not whether you, any of you, agree with that comment. You may all of you disagree with it, feel that is a comment that is not correct. But that is not the test. I will remind you of the test once more. Could a fair-minded man, holding a strong view, holding perhaps an obstinate view, holding perhaps a prejudicial view - could a fair minded man have been capable of writing this?"

[57] On this issue, the High Court did not explain its findings that the comment made by the respondent was not one that a fair-minded person could have honestly made based on the facts that were available to him at the time.

[58] In considering this issue, it is relevant to note the circumstances leading to the press conference held by the respondent on 7 March 2012. In 2011, the Auditor-General audited the performance of the Project. The Auditor- General's report was presented to Parliament in October 2011. The failures and the weakness of the Project were highlighted in the report. As public funds were involved the report by the Auditor-General drew public's attention. The disclosure created grave public concern as it raised the issue of accountability, transparency and good governance in respect of those involved in the affairs of managing public funds. It received wide media coverage and was also subject to much debate in Parliament at the material time.

[59] As I have indicated earlier there was sufficient substratum of facts to warrant the respondent making the Impugned Statement. In this context, it is relevant to note that it was the finding of the High Court that the respondent had an honest belief that his allegations were true and that he was performing a public duty in agitating for greater accountability for public funds.

[60] Given all this, in my view, the respondent's conclusion that public fund had been misused as a leverage for the Public Bank's loan was an opinion and inference that a fair-minded person would have honestly made in the circumstances.

[61] In light of all the above, all the four (4) elements of fair comment as laid down in Joshua Benjamin (supra) had been established. Therefore, the respondent could not be liable for damages for defamation.

The Issue Of Malice

[62] That leaves me to deal with Questions 6 (a) and (b). As can be seen, the crux of the questions essentially relates to the issue of malice. In this regard, it must be emphasised that the High Court made an express finding that the respondent was not motivated by malice in making the defamatory statements. In doing so, the High Court explained that "although the respondent did not care for the effect that his statements may have had on the [Appellants], ... he nonetheless had an honest belief firstly that his allegations were true and that secondly that he was performing a public duty in agitating for greater accountability for public funds", and concluded that the appellants had failed to prove malice on the part of the respondent. The Court of Appeal did not disturb those findings. In this regard, it is trite law that proof of malice defeats the defence of fair comment because a comment that is made maliciously is not fair comment (see Thomas v. Bradbury, Agnew & Co Ltd [1906] 2 KB 627 and Dato' Seri Mohammad Nizar Jamaluddin (supra)). Taking into account that the Impugned Statement was made without malice, the respondent could for that reason resort to the defence of fair comment. Consequently, it is unnecessary to answer Questions 6 (a) and (b).

Conclusion

[63] In all the above circumstances, this appeal must be dismissed. I agree with the order of the Court of Appeal though on substantially different grounds.

[64] My learned sisters Zaleha Yusof, FCJ and Zabariah Mohd Yusof, FCJ have read my judgment in draft and have expressed their agreement with it and have agreed to adopt the same as the judgment of this Court.