Federal Court, Putrajaya

Abang Iskandar Abang Hashim CJSS, Vernon Ong, Zabariah Mohd Yusof, Hasnah Mohammed Hashim, Harmindar Singh Dhaliwal FCJJ

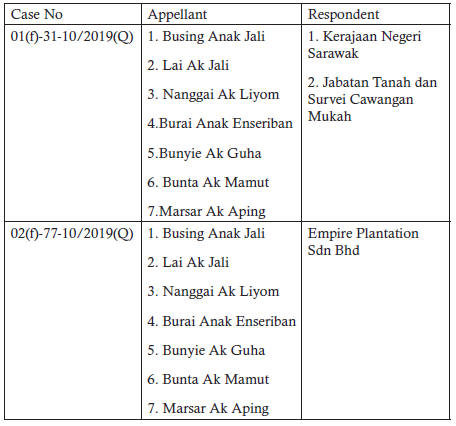

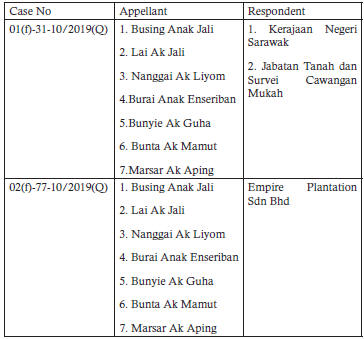

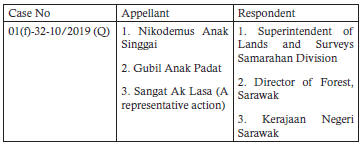

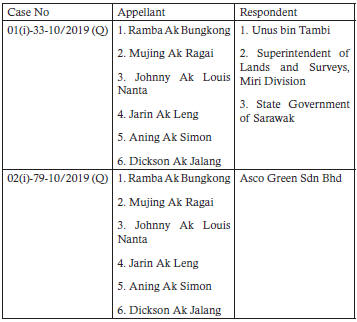

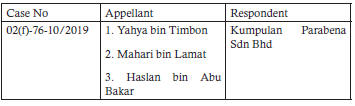

[Civil Appeal Nos: 01(f)-31-10-2019(Q), 02(f)-77-10-2019(Q), 01(f)-32-10- 2019(Q), 01(i)-33-10-2019(Q), 02(i)-79-10-2019(Q) & 02(f)-76-10-2019(Q)]

24 November 2021

Constitutional Law: Courts - Federal Court - Review of previous decision - Whether any reasons for court to review its previous decision

Land Law: Customary land - Proof of custom - Customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau - Whether decision relating to said practices in Director of Forest, Sarawak & Others v. TR Sandah Tabau & Others and Other Appeals could be reviewed - Whether amendments to Land Code (Sarawak) (Cap 81) preserved said practices - Whether native customary rights was a qualifying factor to indefeasibility of title - Whether an extinguishment exercise of native customary rights over land required prior to alienation of lease of State Land - Whether provisions of s 6A of the Land Code (Sarawak) (Cap 81) applicable in these appeals

Native Law and Customs: Land dispute - Customary rights over land - Customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau - Whether decision relating to said practices in Director of Forest, Sarawak & Others v. TR Sandah Anak Tabau & Others and Other Appeals could be reviewed - Whether amendments to Land Code (Sarawak) (Cap 81) preserved said practices

Statutory Interpretation: Retrospective operation - Legislative intention - Section 6A of Land Code (Sarawak) (Cap 81) - Whether said section applied to present appeals

These appeals concerned the appellants' dispute over their native customary right ('NCR') in Sarawak. At the High Court, the trial judge decided that the appellants had proved the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau over land within the district of Simunjan, Sarawak ('the said land'). On appeal, the Court of Appeal reversed the decision of the High Court and ruled that based on the decision of Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals ('TR Sandah 1'), the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau were not customs or usages having the force of law in the Sarawak State Laws; and that the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau must be for the whole community, and since the claim was not a representative action but was only for the seven appellants, it must fail. Consequently, the main issues for determination in these appeals were, whether the majority decision of the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1 should be reviewed and overturned, and Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau restored as customary practices having the force of law; whether the amendment to the Land Code (Sarawak) (Cap 81) ('SLC') in 2018 which came into force on 1 August 2019 had the effect of reversing the ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau in TR Sandah 1; whether the Federal Court should depart from the decision in TH Pelita Sadong Sdn Bhd & Ors v. TR Nyutan Ak Jami & Ors and Another Appeal ('TR Nyutan') on the indefeasibility of the lease of State Land; whether an extinguishment exercise of NCR over land as provided under s 15 of the SLC was required prior to the alienation of lease of State Land; and whether the provisions of s 6A of the SLC were applicable in these appeals.

Held, per Abang Iskandar Abang Hashim, CJSS:

(1) In the present case, there was no conflicting apex court's decision or per incuriam. In fact, TR Sandah 1 had gone through at least three judicial scrutinises in TR Sandah Ak Tabau & Ors v. Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor And Other Appeals; Jeli Naga & Ors v. Tung Huat Pelita Niah Plantation Sdn Bhd & Ors; and Binglai Anak Buassan & 9 Ors v. Entrep Resources Sdn Bhd & 3 Ors; and in those cases, the majority ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau in TR Sandah 1 was not shown to be made per incuriam. There was also no prior Federal Court decision in direct conflict with TR Sandah 1. Applying the guidance on the apex court departing from its own ruling in Tunde Apatira & Ors v. PP, the ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau was based on an extensive assessment of the laws, both written and unwritten, and the differences, if any, between the judges in TR Sandah 1 were due to their individual interpretation and construction of the written laws vis-a-vis the unwritten law, ie the customary law. It was therefore not appropriate for this court to determine whether or not they interpreted or applied the law correctly, for that was a matter of opinion. Moreover, the ruling in TR Sandah 1 had been addressed through a legislative intervention by way of amendments made to the SLC in 2018. Such intervention was what the Federal Court in Dalip Bhagwan Singh v. PP had referred to as "the correction of error was normally dependent on the legislative process." Hence, there was no need to revisit or review TR Sandah 1. (paras 60-64)

(2) Although the 2018 amendments to the SLC did not contain any express provision to say that those amendments were intended for it to operate retrospectively, the words in s 6A(6) of the SLC in respect of the Native Territorial Domain provided a "saving" clause to courts' decisions that had been finally decided prior to 1 August 2019, as opposed to those which had not been finally decided, as either pending trial, or appeals which had yet to be finally determined. Therefore, all final decisions following TR Sandah 1 handed down before 1 August 2019 were preserved. (paras 78-79)

(3) While NCR was statutorily acknowledged in the SLC, in the absence of a clear and unambiguous express provision, it could not be concluded that NCR, in the scheme of the SLC was a qualifying factor to indefeasibility of title. As it stood, fraud was the only stated factor, if pleaded and established by the party who asserted it, that could render a registered title defeasible. Even a failure to comply with s 15 of the SLC on extinguishment prior to alienation could not defeat a registered title so obtained. As held by the apex court in TR Nyutan, the remedy open to the aggrieved party was in damages by way of compensation, under s 197 of the SLC. Consequently, the phrase "Subject to this Code" in s 132(1) of the SLC did not make the NCR as the qualifying factor to indefeasibility other than what was expressly stated therein. (paras 124-125)

(4) The SLC was clearly protective of NCR whereby alienation of State Land or use for a public purpose were prohibited for land which was encumbered with NCR lawfully created under s 5 of the SLC or land which had been issued with native communal title under s 6A of the NLC until and unless all native customary rights had been surrendered or extinguished or provisions for compensating the persons entitled thereto have been made. Further, s 5(3) of the SLC provided proper procedures for extinguishment of NCR created under the said provision. Accordingly, an extinguishment exercise of NCR over land as provided under s 15 of the SLC was required prior to the alienation of lease of State Land. (paras 128, 129 & 131)

(5) As at 1 August 2019, s 6A of the SLC should be the governing provision on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau for the lban community; and from that same date onwards, the ruling in TR Sandah 1 on the said matter had no force of law, was no longer a valid authority; and the court was duty bound to give effect to the statutory law. In this instance, given the peculiar circumstances of these appeals whereby they were commenced under s 5 of the SLC and proceeded throughout until they reached the apex court when the amendments had already been in force, s 6A of the SLC was applicable here. (paras 155-157)

Case(s) referred to:

AG. v. Prince Ernest Augustus of Hanover [1957] AC 436 (refd)

Alma Nudo Atenza v. PP & Another Appeal [2019] 3 MLRA 1 (refd)

Arulpragasan Sandaraju v. PP [1996] 1 MLRA 588 (refd)

Asean Security Paper Mills Sdn Bhd v. Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance (Malaysia) Bhd [2008] 2 MLRA 80 (refd)

B Surinder Singh Kanda v. The Government Of The Federation Of Malaya [1962] 1 MLRA 233 (refd)

CTEB & Anor v. Ketua Pengarah Pendaftaran Negara Malaysia & Ors [2021] 4 MLRA 678 (refd)

Dalip Bhagwan Singh v. PP [1997] 1 MLRA 653 (refd)

Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [2021] 2 MLRA 190 (refd)

Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91 (folld)

Golden Star & Ors v. Ling Peek Hoe & Ors [2021] 2 MLRA 150 (refd)

Government Of The Federation Of Malaya v. Surinder Singh Kanda [1960] 1 MLRA 458 (refd)

Heydon's Case 76 Er 637; (1584) 3 Co Rep 7; [1584] 1 WLUK 42 (refd)

Husli Mok v. Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys & Anor [2015] 2 MLRA 195 (refd)

Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Shri Raj Narain [1975] 2 SCC 159 (refd)

Inland Revenue Commissioners v. Hinchy [1960] 1 All Er 505 (refd)

Ireka Engineering & Construction Sdn Bhd v. PWC Corporation Sdn Bhd & Other Appeals [2019] 6 MLRA 1 (refd)

Jeli Naga & Ors v. Tung Huat Pelita Niah Plantation Sdn Bhd & Ors [2019] 6 MLRA 287 (refd)

Khoo Hi Chiang v. Public Prosecutor And Another Case [1993] 1 MLRA 701 (refd)

Kleinwort Benson Ltd v. Lincoln City Council [1998] 3 WLR 1095 (refd)

Letchumanan Chettiar Alagappan @ L Allagappan & Anor v. Secure Plantation Sdn Bhd [2017] 3 MLRA 501 (refd)

Ling Peek Hoe & Anor v. Ding Siew Ching & Another Appeal [2017] 4 MLRA 372 (refd)

Mabo and Others v. Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1 (refd)

Majlis Agama Islam Wilayah Persekutuan v. Victoria Jayaseele Martin & Another Appeal [2016] 3 MLRA 1 (refd)

Maxwell v. Murphy (1957) 96 CLR 261 (refd)

Muhammed Hassan v. PP [1997] 2 MLRA 311 (refd)

Munusamy Vengadasalam v. PP [1986] 1 MLRA 292 (refd)

Nikodemus Singai & Ors v. Sibu Slipway Sdn Bhd & Ors [2010] 14 MLRH 269 (refd)

PP v. Mohd Radzi Abu Bakar [2005] 2 MLRA 590 (refd)

PP v. Richard Kwan [1970] 1 MLRH 92 (refd)

PP v. Tan Tatt Eek & Other Appeals [2005] 1 MLRA 58 (refd)

Public Prosecutor v. Dato' Yap Peng [1987] 1 MLRA 103 (refd)

R v. Zeoikowski [1989] 1 SCR 1378 (refd)

Ramanathan Yogendran v. PP [1995] 2 SLR 563 (refd)

Smith v. London Transport Executive [1951] AC 555; [1951] 1 All ER 667 (refd)

Sinnaiyah & Sons Sdn Bhd v. Damai Setia Sdn Bhd [2015] 5 MLRA 191 (refd)

Spectrum Plus Ltd, Re; National Westminster Bank Plc v. Spectrum Plus Ltd [2005] UKHL 41 (refd)

ST Sadiq v. State Of Kerala [2015] 4 SCO 400 (refd)

Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys Bintulu v. Nor Nyawai & Ors And Another Appeal [2005] 1 MLRA 580 (refd)

Tan Boon Kean v. PP [1995] 2 MLRA 28 (refd)

TH Pelita Sadong Sdn Bhd & Anor v. TR Nyutan Jami & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 2 SSLR 543; [2017] 6 MLRA 189 (folld)

TR Sandah Ak Tabau & Ors v. Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor And Other Appeals [2019] 5 MLRA 667 (folld)

Tunde Apatira & Ors v. PP [2000] 1 MLRA 800 (refd)

Warburton v. Loveland d. Iview (1828), 1 Hud & B 623 (refd)

Yong Tshu Khin & Anor v. Dahan Cipta Sdn Bhd & Anor And Other Appeals [2021] 1 MLRA 1 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Administration of Islamic Law (Federal Territories) Act 1993, s 59(1)

Federal Constitution, arts 140(1), 144(1), 160(2)

Rules of Court 2012, O 14A, O 18 r 19

Rules of the Federal Court 1995, r 137

Sarawak Land Code (Cap 81), ss 2, 4(4), 5(3), (7), 6, 6A(6), 10, 13(1), 15, 18, 18A, 28, 29(1), 82, 88, 130(2), 132(1), 197

Other(s) referred to:

NS Bindra, Interpretation of Statutes, 2002, 9th edn, p 645

Maxwell, Interpretation of Statutes,3rd edn, p 28

Sullivan on the Construction of Statutes, LexisNexis, 2014, 6th edn, p 405

Counsel:

For the Civil Appeal No: 01(f)-31-10-2019 (Q)

For the appellant: Mekanda Singh Sandhu (M Izayyeem Azim & Paul Raja with him); M/s Sagau, Raja & Co

For the respondent: Mohd Adzrul Adzlan (Anisa Fadhillah Mohamed Jamel with him); AG's Chambers, Sarawak

For the Civil Appeal No: 02(f)-77-10-2019 (Q)

For the appellant: Mekanda Singh Sandhu (M Izayyeem Azim & Paul Raja with him); M/s Sagau, Raja & Co

For the respondent: Danny Huang Dung Po; M/s Huang & Co Advocates

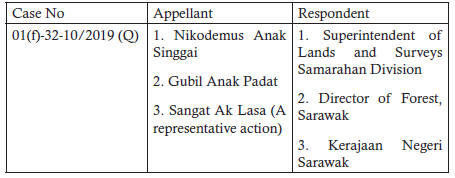

For the Civil Appeal No: 01(f)-32-10-2019 (Q)

For the appellant: Dominique Ng Kim Ho (Berrylin Ng Phuay Lee with him); M/s Dominique Ng & Associates

For the respondent: Mohd Adzrul Adzlan (Ronald Felix Hardin with him); AG's Chambers, Sarawak

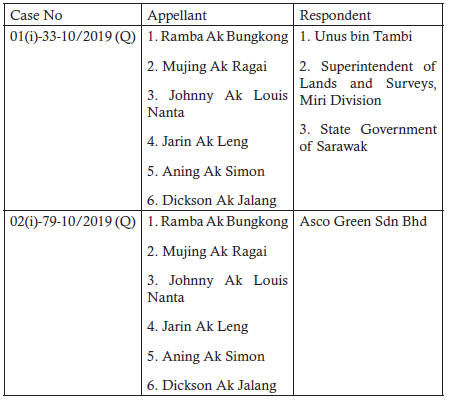

For the Civil Appeal No: 01(i)-33-10-2019 (Q)

For the appellant: Simon Siah (Clarice Chan & Joshua Baru with him); M/s Simon Siah Chua and Chow Advocates

For the respondent: Mohd Adzrul Adzlan (Ronald Felix Hardin with him); AG's Chambers, Sarawak

For the Civil Appeal No: 02(i)-79-10-2019 (Q)

For the appellant: Simon Siah (Clarice Chan & Joshua Baru with him); M/s Simon Siah, Chua and Chow Advocates

For the respondent: Gabriel CH Kok (Amanda Yong with him); M/s Khoo & Co Advocates

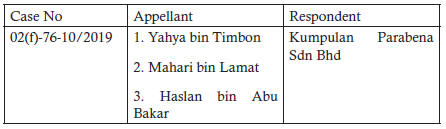

For the Civil Appeal No: 02(f)-76-10-2019 (Q)

For the appellant: Dominique Ng Kim Ho (Berrylin Ng Phuay Lee with him); M/s Dominique Ng & Associates

For the respondent: Tony Lim Lee Tom (Nathan Ting with him); M/s Satem, Chai & Dominic Lai Advocates

JUDGMENT

Abang Iskandar Abang Hashim CJSS:

Introduction

[1] There are six appeals that were heard together despite there being different parties involved, except in two cases - Case A and Case C (which will be enumerated later) where the parties are the same. We heard oral submissions by all learned counsel representing the respective parties on two separate dates. At the end of those submissions, we stood down for the panel members to deliberate. Unfortunately, we were not able to come up with a decision on that day. We therefore indicated to all learned counsel that we needed a bit of time to consider the respective submissions and that they would be informed once a decision is reached pertaining to each of these appeals, in due course. We have now reached our decisions and what follow below are our deliberations of the issues raised and our reasons as to why we have so decided.

[2] My learned brothers Justices Vernon Ong and Harmindar Singh Dhaliwal and my learned sisters Justice Zabariah Mohd Yusof and Justice Hasnah Mohammed Hashim had read this judgment in draft and they had indicated to me their agreement with it and that it becomes the judgment of this Court.

[3] Although there have been not a few issues raised in the questions that were posed before this Court for our considerations, we observed that there were some common issues that transcended most of the appeals. The main commonality in these cases has been the very subject matter of dispute - the native customary right ("NCR") in Sarawak; and the questions of law for this Court's determination - on matters relating to the Federal Court decisions in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91 ("TR Sandah 1"), TH Pelita Sadong Sdn Bhd & Anor v. TR Nyutan Jami & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 2 SSLR 543; [2017] 6 MLRA 189 ("TR Nyutan") and the Court of Appeal decision in Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys Bintulu v. Nor Nyawai & Ors And Another Appeal [2005] 1 MLRA 580 ("Nor Ak Nyawai") vis-a-vis the 2018 Amendments to the Sarawak Land Code ("SLC").

[4] For clarity and better understanding of the issues in question, it is pertinent for us to provide a brief history of the facts of each case which finally culminated in the framing of the questions for the Court's determination.

Brief Background Of The Cases

CASE A

[5] The question of law for this court's determination is framed in the following manner:

Whether it is correct in law or proper for the Court of Appeal to set aside the trial judge's finding of fact that the plaintiffs have acquired and/or created individual or communal native customary rights over State land in Sarawak on the application as a matter of law of the decision in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91.

[6] In this case, the High Court Judge had, on 3 February 2014, decided upon a full trial that the appellants had acquired and/or created individual or communal NCR over 1391.42 acres of land within the 4460.00 hectares more or less of the Provisional lease Lot 11 granted to Empire Plantation Sdn Bhd In his judgment, the Judge was satisfied, on the balance of probabilities that the appellants had proved the NCR of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau over the said land. The aggrieved defendants appealed against that decision.

[7] On appeal, the Court of Appeal reversed the decision of the High Court Judge and ruled that based on the decision of TR Sandah 1, the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau were not customs or usages having the force of law in the Sarawak State Laws as defined in art 160(2) of the Federal Constitution.

[8] The Court of Appeal further stated that the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau must be for the whole community, and since the claim was not a representative action but was only for the seven appellants, it must necessarily fail. It was this aspect of the Court of Appeal's decision that the appellants sought this court's consideration to answer additional question as to "whether the claim for NCR based on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau must be for the whole community and not for the appellants only" (the Court of Appeal's decision was made on 13 July 2017).

[9] Clearly, the question for this court's determination concerns the correctness of the Court of Appeal's application of the majority ruling in TR Sandah 1 in respect of the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau to the finding of facts and the decision of the High Court Judge.

CASE B

[10] The question of law for the court's determination is as follows:

Whilst the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau do not appear in any codified law under the Rajahs, their existence had been acknowledged in the Reports and historical texts, whereas it is axiomatic that customary rights do not owe their existence to statute; instead, they are recognised as a source of unwritten laws, and as such, whether the majority decision of Federal Court in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91 with respect to customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau should be reviewed, and overturned, and Pemakai Menoa and Pulau restored as customary practices having the force of law.

[11] This case is a representative action brought on behalf of the claimants and all others who claimed native customary rights over land at or around Kampung Spaoh, Kampung Menat Ulu and Kampung Menat Hi at Gedong in the district of Simunjan, Sarawak.

[12] In this case, there were initially six respondents including the three above, namely Sibu Slipway Sdn Bhd, the holder of Forest Licence No 8393; Lambang Sinar Mas Sdn Bhd, the holder of two leases described as Lot 226 Block 4 Sedilu-Gedong Land District and Lot 1 Block 9 Sedilu-Gedong Land District; and Indranika Jaya Sdn Bhd, the holder of a lease described as Lots 164, 162 and 173 of Sedilu-Gedong Land District.

[13] However, these three parties were removed from the suit by virtue of their successful striking out applications primarily due to their holding of the indefeasibility of title of the license and the lease as demonstrated in Nikodemus Singai & Ors v. Sibu Slipway Sdn Bhd & Ors [2010] 14 MLRH 269 ("Nikodemus 1"). Hence, the full trial of the matter proceeded only against the Superintendent of Lands and Surveys Samarahan Division, Director of Forest, Sarawak and Kerajaan Negeri Sarawak.

[14] At the High Court, the Judge found on 11 August 2014, on the strength of the evidence presented after a full trial, that the appellants had successfully proved, on the balance of probabilities, that they had acquired, created and/ or inherited NCR prior to the 1 January 1958 over the disputed areas of 8001 hectares over which the forest timber license and leases were issued. Of the 8001 hectares, were cultivation mosaics measuring approximately 300 hectares.

[15] However, in view of the earlier judgment in Nikodemus 1 on indefeasibility of titles, the Judge varied the earlier order and decided that an award of general damages to be assessed by the SAR against the respondents for loss of the appellants' native customary rights over the entire disputed areas which have been alienated to the named licensee and lessees above. This variation order was made on 10 September 2014.

[16] On Appeal, the Court of Appeal decided on 13 July 2017 that the appellants are only entitled to the NCR over the 300 hectares of cultivation mosaics - the agreed temuda, but not to the entire areas of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau, based on the decision of the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1.

CASE C

[17] At the High Court, Asco Green Sdn Bhd was the plaintiff, and the appellants were the defendants while Unus bin Tambi, Superintendent of Lands and Surveys, Miri Division and State Government of Sarawak were made 3rd parties. Asco Green sued the appellants for a right to vacant possession; order of eviction; and declarations that the appellants were trespassers and illegal occupiers on the land it held on a lease.

[18] Asco Green then sought for a summary judgment under O 14A of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC") as well as for striking out the appellants' defence and counterclaim under O 18 r 19 of the ROC. The 3rd parties similarly filed for striking out of the appellants' statement of claim against them. These applications were allowed on 3 November 2017, hence the appellants' defence and counterclaim against Asco Green Sdn Bhd and their statement of claim against the 3rd party were struck out.

[19] Judgment was also entered against the appellants under O 14A of the ROC based on the following main reasons:

i. That Asco Green Sdn Bhd, as the registered proprietor of an area approximately 707 hectares described as Lot 130 Block 3 Bakong Land District for the lease of the said land holds an indefeasible title.

ii. Based on the affidavit evidence, the disputed area of Lot 130 was a primary forest in 1947 and 1963 with no proof of cultivation or settlement.

iii. The claim of NCR over the area for foraging food, deriving valuable medicines, wildlife and other forest produce for livelihood and sustenance in the context of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau are not maintainable because they are customs that have no force of law as ruled by the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1.

[20] The Court of Appeal upheld the decision of the High Court on 20 February 2019 and ruled that the disposal of the matter summarily under O 14A; and O 18 r 19 of the ROC against the appellants was proper on the facts and circumstances of the case.

[21] The question of indefeasibility of title held by Agro Green was a non-issue, on top of the absence of any allegation of fraud in the pleading either against Agro Green or the 3rd parties. Hence the absence of any vitiating factor defeating Agro Green's right as the registered proprietor of Lot 130.

[22] The Court of Appeal also held that the legal status of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau have been firmly established by the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1 as having no force of law, that they cannot be grounds for claims of NCR. As a corollary, the question of extinguishment of NCR land did not arise.

[23] Following the decision of the Court of Appeal, four questions of law were framed by the appellants for this Court's determination, as follows:

(i) Whether the Court of Appeal's decision in Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys Bintulu v. Nor Nyawai & Ors And Another Appeal [2005] 1 MLRA 580 that the rights of the natives are confined to the area where they settled and not where they foraged for food is a correct statement of law relating to the extent and nature of rights to land claimed under native customary rights in Sarawak.

(ii) Whether the alleged practice of the Iban to preserve an area of jungle or forests as "Pulau" for access for food, wildlife and forest produce, gives rise to exclusive rights to the land in the "Pulau".

(iii) Whether an extinguishment exercise of native customary rights over land as provided under s 15 of the Sarawak Land Code (Cap 81) is required prior to the alienation of lease of state land; and

(iv) If the answer to (iii) is in the positive, whether the lease of state land alienated without prior extinguishment of native customary rights is therefore null and void and/or the areas encumbered with native customary rights to be excised out or excluded from the lease of state land.

CASE D

[24] At the High Court, the respondent initially filed separate Originating Summonses ("OS") against each appellant for, inter alia, vacant possession and quiet enjoyment of the lands described as Lots 187 and Lot 188 of Block 10 Lambir Land District which are held on lease for a term of 60 years from 1 September 2009. The said OS were converted to writ actions and jointly tried.

[25] Upon evaluating the evidence, the High Court Judge had, on 17 January 2018, allowed the respondent's claim and dismissed the appellants' counterclaim of NCR over the disputed areas, primarily due to the unsatisfactory and to a certain extent, contradictory evidence.

[26] It was held that in light of the Federal Court's decision in TR Sandah 1, NCR claim does not extend to areas where the natives used to roam to forage for their livelihood. Moreover, there was no evidence of the said lands being cleared or cultivated before 1 January 1958 for the said lands was a virgin forest in 1951 and remained the same in 1961.

[27] The High Court Judge also found that the respondent, as the registered proprietor held indefeasible title over the disputed lands which title was not shown on evidence to have been issued fraudulently or without complying to due processes.

[28] On Appeal, the Court of Appeal unanimously confirmed the findings and the decision of the High Court Judge on 8 January 2019 mainly based on the application of the Federal Court's decision in TR Sandah 1 on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau; and TR Nyutan on indefeasibility of title. The Court of Appeal further noted that amendments to the Land Code in ss 6A and 28 have no bearing on the case as the amendments took effect only on 1 August 2019.

[29] Stemming from the Court of Appeal decision, the following question of law was framed for the Federal Court's determination:

Whether the Federal Court should depart from the decision of the Federal Court in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91 on the question of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau having no force of law and that of TH Pelita Sadong Sdn Bhd & Anor v. TR Nyutan Jami & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 2 SSLR 543; [2017] 6 MLRA 189 on the indefeasibility of the Lease of State Land and if so, whether those cases have any significant bearing on the decision of the Learned Judicial Commissioner in any event?

The Commonality Of The Questions Of Law

[30] Upon analysing the various questions framed for this court's determination, we identified the commonalities of those questions which we would categorise into three main issues and sub-issues as follows:

(i) Reviewing or revisiting earlier decision/s of the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1 (Case B, D) and TR Nyutan (Case D) and of the Court of Appeal in Nor Ak Nyawai (Case C):

(a) The correctness of applying TR Sandah 1 to the trial judge's finding of facts on NCR (Case A).

(b) Communal versus individual NCR (added question in Case A).

(ii) TR Nyutan - on indefeasibility of title and extinguishment of NCR (Case C, D).

(iii) The effects of the 2018 Amendments to the Sarawak Land Code.

Reviewing Or Revisiting Earlier Decisions

[31] There are two modes where this court may assess and examine earlier decisions - through a proper review application under r 137 of the Rules of the Federal Court 1995, or by way of an appeal proper.

[32] The application of r 137 has been succinctly explained by this court in Asean Security Paper Mills Sdn Bhd v. Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance (Malaysia) Bhd [2008] 2 MLRA 80 ("Asean Security") that was followed subsequently by this Court in a number of recent cases such as Golden Star & Ors v. Ling Peek Hoe & Ors [2021] 2 MLRA 150, Yong Tshu Khin & Anor v. Dahan Cipta Sdn Bhd & Anor And Other Appeals [2021] 1 MLRA 1, Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim v. Government Of Malaysia & Anor [2021] 2 MLRA 190, to name a few. In gist, there must be very exceptional circumstance for a review to take place. But we are not concerned with this type of application in this case.

[33] In the present case, three earlier decisions are sought to be revisited - two are the Federal Court's decisions - TR Sandah 1 and TR Nyutan; and one Court of Appeal decision - Nor Ak Nyawai. At the risk of repetition, we find the need to reproduce the three related questions posed to us which are framed in the following manner:

"... whether the majority decision of Federal Court in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91 with respect to customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau should be reviewed, and overturned, and Pemakai Menoa and Pulau restored as customary practices having the force of law. (Case B)

Whether the Court of Appeal's decision in Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys Bintulu v. Nor Nyawai & Ors And Another Appeal [2005] 1 MLRA 580 that the rights of the natives are confined to the area where they settled and not where they foraged for food is a correct statement of law. (Case C)

Whether the Federal Court should depart from the decision of the Federal Court in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91 on the question of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau having no force of law and that of TH Pelita Sadong Sdn Bhd & Anor v. TR Nyutan Jami & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 2 SSLR 543; [2017] 6 MLRA 189 on the indefeasibility of the lease of State Land and if so, whether those cases have any significant bearing on the decision of the Learned Judicial Commissioner in any event. (Case D)"

[34] It was on the basis of the manner as to how the questions of law framed for this court's determination, that the Respondents urged this Court to dismiss the appeals, because these questions sought to review the substantive merits of the Federal Court decision in TR Sandah 1, which should be initiated by a proper review application under r 137 of the Rules of the Federal Court 1995.

[35] In all fairness, there is merit in this argument by the respondents, in that although the words used are review, overturn, restore and depart, these questions have the effect, in pith and substance, of questioning the correctness or otherwise of those very decisions in TR Sandah 1, TR Nyutan and Nor Ak Nyawai.

[36] In fact, we found that the question framed in this case in respect of the correctness of the Court of Appeal's statement in Nor Ak Nyawai to be exactly similar as Question 3 posed to the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1 and Question 1 and 2 in Jeli Naga & Ors v. Tung Huat Pelita Niah Plantation Sdn Bhd & Ors [2019] 6 MLRA 287 ("Jeli Anak Naga") as follows:

TR Sandah 1

"(c) Whether the Court of Appeal's decision in Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys Bintulu v. Nor Nyawai & Ors And Another Appeal [2005] 1 MLRA 580 that the rights of the natives is confined to the area where they settled and not where they foraged for food is a correct statement of the law relating to the extent and nature of rights to land claimed under native customary rights in Sarawak. (Question 3)"

Jeli Anak Naga

"1. Whether the Court of Appeal's decision in Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys Bintulu v. Nor Nyawai & Ors And Another Appeal [2005] 1 MLRA 580 that the rights of the natives is confined to the area where they settled and not where they foraged for food is a correct statement of the law relating to the extent and nature of rights to land claimed under native customary rights in Sarawak [Question 1]"

"2. Whether the alleged practice of the Iban to preserve an area of jungle or forests as "Pulau" for access for food, wildlife and forest produce, give rise to exclusive rights to the land in the "Pulau"? [Question 2]"

[37] Clearly, it could not escape our observation that the questions posed to us which related to the Court of Appeal statements in Nor Ak Nyawai are another attempt of relitigating similar questions of law which this court had, with respect, already answered in TR Sandah 1 and in Jeli Anak Naga.

[38] Having said that however, these six appeals are coming up from the decisions of the Court of Appeal, revolving around issues of the application of TR Sandah 1, TR Nyutan, and Nor Ak Nyawai which directly relate to the 2018 Amendments of the Sarawak Land Code.

[39] For these reasons, we think it is improper to simply dismiss the appeals on the basis of procedural impropriety as submitted by the respondents. These appeals come within what Abdul Hamid Mohamad CJ stated in Asean Security as an attempt to revisit earlier decisions:

"if a party is dissatisfied with a judgment of this court that does not follow the court's own earlier judgments, the matter may be taken up in another appeal in a similar case. That is what is usually called "revisiting"."

What Does TR Sandah 1 Decide?

[40] The main controversial decision of the majority of 3:1 in TR Sandah 1 is the ruling by Raus Sharif PCA [as he then was], agreed to by Ahmad Maarop FCJ [as he then was] that the customs of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau are customs that the laws of Sarawak do not recognise as forming part of the customary laws of the natives of Sarawak and as such, they are customs which have no force of law as envisaged under art 160(2) of the Federal Constitution.

[41] Such view effectively affirmed what the Court of Appeal held in Nor Ak Nyawai that the rights of the natives are confined to the area where they settled and not where they foraged for food, as a correct statement of the law relating to the extent of natives' rights to land claimed under native customary rights in Sarawak.

[42] Following the decision in TR Sandah 1, an application for review under r 137 of the Rules of the Federal Court 1995 was filed and heard. By a majority of 4:1, the Federal Court dismissed the review application. This is reported in TR Sandah Ak Tabau & Ors v. Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor And Other Appeals [2019] 5 MLRA 667 ("TR Sandah 2").

[43] We had occasion to peruse the decisions in both TR Sandah 1 and TR Sandah 2 and found that the approach taken in questioning the decision of the majority in TR Sandah 1 is similar with what was raised in TR Sandah 2 and the present appeals. In fact, similar argument was also taken up and raised in the Federal Court case of Jeli Anak Naga.

[44] We hereby summarise the gist of the parties' submissions on this issue.

The Parties' Submissions

Errors In TR Sandah 1

[45] The appellants submitted that the majority in TR Sandah 1 fell into a serious error when ruling that Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau as having no force of law, based on the following reasons:

(i) Failure to consider the recognition of English common law on custom as part of the laws of Sarawak in Rajah's Order No L-4 1928; and the Notes for the Guidance of Officers in Interpreting Order No L-4,1928. The customs of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau satisfy the tests and the essential elements of a custom in the above laws and are therefore legally enforceable rights.

(ii) The nature of the native customary law as being unwritten and sui generis, flexible and adaptable to the needs of the community. They do not owe their existence to statute. Rather, the binding effect of the customs comes from the custom being generally accepted and having the assent of the native community. Acknowledgment of only codified customs in statute, which become positive law, undermines the position of the native custom or native customary law as "existing law" under art 162 of the Federal Constitution.

(iii) The failure to recognise the method of establishing customary right to land by way of "any other lawful method" in s 5(2)(f) of the Sarawak Land Code.

[46] On points (i) and (ii) above, the respondents argued before us that the appellants' line of arguments above have been dealt with and ventilated in extenso by the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1.

[47] It was further contended on behalf of the respondents that the Rajah's Order No L-4 1928; and the Notes for the Guidance of Officers in Interpreting Order No L-4, 1928 are applicable only in respect of certain branches of law which are silent or where laws are yet to be enacted for. Hence, they do not cover land matters because they are already governed by various existing laws such as the Rajah's Order 1875; the Fruit Trees Order 1899; the Land Order 1920; the Land Settlement Ordinance 1933; Secretariat Circular 1939; Tusun Tunggu; and s 5 of the Land Code. As such, the customary practice of Temuda or clearing of virgin forest for cultivation and the principle of continuous occupation are the only recognised and enforceable NCR. In other words, the omissions in relation to Pemakai menoa and Pulau Galau must have been deliberate.

[48] The respondents further submitted that the decision of the majority in TR Sandah 1 stands as good law and was followed by subsequent Federal Court decisions in Jeli Anak Naga and Binglai Anak Buassan & 9 Ors v. Entrep Resources Sdn Bhd & 3 Ors (unreported). The dismissal of the review application in TR Sandah 2 further strengthens the case that there is no justifiable reason for departing from the ruling in TR Sandah 1 in respect of the customs of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau.

[49] Regarding point (iii), the respondents argued that it was not possible for the Federal Court to consider "any other lawful method" under para (f) as the customs claimed must firstly be proved to be lawful within the meaning of art 160(2) of the Federal Constitution. Therefore, although the practices of Pemakai Menoa or Pulau Galau exist as Iban customs, they are nevertheless not legally enforceable.

The Ruling On Pemakai Menoa And Pulau Galau - 3:1 Or 2:2? Legal Reasoning Versus Decision

[50] The appellants submitted that it is the legal reasoning and not the decision that binds the courts below in the application of the principle of stare decisis. Hence, stare decisis was argued to be operative only when there is conclusive legal precedent.

[51] In this respect, the appellants argued that revisiting TR Sandah 1 is necessary for want of clarity on the legal position because a close scrutiny of the ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau reveals that there was, in actual fact, a split of 2:2 and not 3:1. This is because, Abu Samah Nordin FCJ who formed part of the majority viewed that Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau are legally recognised customs - consistent with the dissenting view of Zainun Ali, FCJ - but which must be proved on evidence, which in his view, the appellants had failed to do.

[52] Therefore, the appellants urged that this court would, in fact be obliged to look at the reasoning rather than the decision in TR Sandah 1 on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau. The appellants argued that since there is no majority decision on the principle of law relating to Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau, there is no obligation by the courts below, by way of stare decisis, to apply the decision of TR Sandah 1, and so, this Court is at liberty to differ from what Raus Sharif PCA and Ahmad Maarop FCJ held on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau.

[53] The respondents on the other hand contended that this line of argument has been raised in TR Sandah 2, Jeli Anak Naga and Binglai Anak Buassan and the Federal Court has consistently confirmed that the decision in TR Sandah 1 is a decision of the majority of 3:1 and not 2:2.

[54] The respondents further argued that departing from TR Sandah 1 would mean departing from all other decisions of the Federal Court adopting and confirming the said decision, which effectively will result in further uncertainties and chaos, considering the statutory intervention by the 2018 Amendments to the Sarawak Land Code.

Judicial Precedent In The Apex Court - When To Depart From Earlier Decision?

[55] At the outset, we are fully aware of the facts that these lines of submissions challenging/defending TR Sandah 1 were raised, presented and argued in TR Sandah 2, Jeli Anak Naga and Binglai Anak Buassan and the Federal Court had, in these cases found no reasons to depart from its earlier decision in TR Sandah 1.

[56] Faced with similar application of reviewing or revisiting this court's earlier decisions, we think it is proper to first lay down the legal principles governing the exercise of power to revisit earlier decisions in the context of the rule of judicial precedent in the apex court.

[57] The case of Dalip Bhagwan Singh v. PP [1997] 1 MLRA 653 ("Dalip Bhagwan") provides guidance as to what factors to consider when dealing with the question of judicial precedent and its exceptions. The first factor where this Court may depart from earlier decision is the existence of conflicting decisions of the Federal Courts over the same subject matter. The other factor is decision made per incuriam - which correction of error is normally dependent on legislative process. It was held that:

"The rule of judicial precedent in relation to the House of Lords was stated in London Tramways v. London County Council [1898] AC 375 that it was bound by its own previous decision in the interests of finality and certainty of the law, but a previous decision could be questioned by the House when it conflicted with another decision of the House or when it was made per incuriam, and that the correction of error was normally dependent on the legislative process.

However, in 1966, Lord Gardiner LC made the following statement on behalf of himself and all the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary commonly known as the Practice Statement (Judicial Precedent) 1966 which is set out below:

Their Lordships regard the use of precedent as an indispensable foundation upon which to decide what is the law and its application to individual cases, it provides at least some degree of certainty upon which individuals can rely in the conduct of their affairs, as well as a basis for orderly development of legal rules.

Their Lordships nevertheless recognise that too rigid adherence to precedent may lead to injustice in a particular case and also unduly restrict the proper development of the law. They propose, therefore, to modify their present practice and, while treating former decisions of this House as normally binding, to depart from a previous decision when it appears right to do so."

[58] Our judicial history shows that this Court had previously undertaken such exercise of overruling or departing from earlier decisions in the context of the standard of proof at the end of prosecution's case. We see how the law had developed where the ruling of the Supreme Court in this respect in Munusamy Vengadasalam v. PP [1986] 1 MLRA 292, was overruled by the Supreme Court in Khoo Hi Chiang v. Public Prosecutor And Another Case [1993] 1 MLRA 701 which subsequently was partly overruled by the Federal Court in Tan Boon Kean v. PP [1995] 2 MLRA 28. Tan Boon Kean was in turn overruled by the majority judgment of the Federal Court in Arulpragasan Sandaraju v. PP [1996] 1 MLRA 588. The 'beyond reasonable doubt standard' by the majority of 4:3 in Arulpragasan led to the amendment to the Criminal Procedure Code in 1997 via Act A979 which took effect on 31 January 1997, which saw the articulation of the prima facie proof that the prosecution is obligated to establish before the accused person is legally obliged to enter on his or her defence.

[59] So, we see how the Federal Court in Dalip Bhagwan case guides us in dealing with the questions of the application of judicial ruling for the courts below by way of stare decisis and the impact of a legislative action in the following manner:

"When leave was granted in February 1991 to refer Question 2 posed to us and as set out above, and for that matter, when the High Court heard the appeal in 1990 from the decision of the sessions court in question, the legal position of the burden of proof at the close of the prosecution's case was still governed by the test of prima facie case as in Munusamy's case, so in answering the question cast in the past tense to indicate 1990, it should be borne in mind that the position of law referred to was as in 1990.

The answer to Question 2 therefore is in the affirmative.

In this connection, if Question 2 had not been framed in the past tense so as to require an answer applicable in 1990 about the burden of proof at the close of the prosecution's case, but if it were cast in the present tense instead, then it is piquant that the sessions court would have been right in so assessing the reliability, etc of prosecution witnesses at the close of the prosecution's case, because, at the time of our hearing this reference, the burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt at the close of the prosecution's case as enjoined by the ratio of the Arulpragasan's case would be applicable subject to what we have to say about the latest amendment to the Criminal Procedure Code (FMS Cap 6).

...

The true position of the legal burden of proof at the close of the prosecution's case with regard to the amendment to the Criminal Procedure Code in question would have to be dealt with as the said amendment had already come into effect before we heard this criminal reference. We should deal with it presently.

...

The said amendment would apply, in our view, only to an act or omission constituting a criminal offence committed on or after 31 January 1997, and not to any such act or omission before 31 January 1997. For such act or omission committed before 31 January 1997, the test laid down in Arulpragasan's case, ie that of proof beyond a reasonable doubt at the close of the prosecution's case, would still apply. We have to and we would presently give our reasons for saying so.

Parliament has plenary power to make retrospective criminal and civil law vide Loh Kooi Choon v. Government of Malaysia [1975] 1 MLRA 646, but when it makes such retrospective criminal law, it must steer clear of art 7, or for the purpose of the instant case, art 7(1) of the Federal Constitution."

[60] In the present case, both factors mentioned in Dalip Bhagwan case above are absent - conflicting apex court's decisions or per incuriam. In fact, TR Sandah 1 has gone through at least three judicial scrutinies in TR Sandah 2, Jeli Anak Naga and Binglai Anak Buassan and in these cases, the ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau by Raus Sharif PCA supported by Ahmad Maarop FCJ was not shown to be made per incuriam. There was also no prior Federal Court decision in direct conflict with TR Sandah 1. Therefore, the question that needs to be asked is whether there is a necessity to revisit or review TR Sandah 1?

[61] With respect, our answer is that we do not find the need to do so. In the Federal Court case of Tunde Apatira & Ors v. PP [2000] 1 MLRA 800 ("Tunde Apatira"), the prosecution invited the Court to depart from its ruling against double presumption in Muhammed Hassan v. PP [1997] 2 MLRA 311 that was argued to be wrongly decided and ought no longer to be applied. In rejecting the prosecution's submission on the alleged errors in Muhammed Hassan, Gopal Sri Ram JCA delivering the judgment of the court stated three reasons for such rejection - recent superior court decision; certainty; and the logic and reasoning of earlier decision based on the construction of statutory provision. He held as follows:

"With respect, we are unable to accept the learned deputy's invitation to depart from Muhammed bin Hassan for three reasons. In the first place Muhammed bin Hassan is a very recent decision of this court. It is bad policy for us as the apex court to leave the law in a state of uncertainty by departing from our recent decisions. Members of the public must be allowed to arrange their affairs so that they keep well within the framework of the law. They can hardly do this if the judiciary keeps changing its stance upon the same issue between brief intervals. The point assumes greater importance in the field of criminal law where a breach may result in the deprivation of life or liberty or in the imposition of other serious penalties. Of course, if a decision were plainly wrong, it would cause as much injustice if we were to leave it unreversed merely on the ground that it was recently decided. In a case as the present this court will normally follow the approach adopted by the apex courts of other Commonwealth jurisdictions as exemplified by such decisions as R v. Shivpuri [1986] 2 All ER 334.

The second reason is closely connected to the first. It also has to do with certainty in the law. The decision in Muhammed bin Hassan has been affirmed by our courts (see PP v. Ong Cheng Heong [1998] 2 MLRH 345) and convictions have been quashed by this court acting on its strength. See, for example Haryadi Dadeh v. PP [2000] 1 MLRA 397. If we accept the learned deputy's invitation to depart from Muhammed bin Hassan, it will throw the law into a state of uncertainty and cast doubt on the accuracy of the pronouncements made in those cases that have so recently applied the interpretation formulated in that case. It is bad policy for us to keep the law in such a state of flux especially upon a question of interpretation of a statutory provision that comes up so often for consideration before the courts.

Lastly - and this is the most important reason - we agree with the interpretation placed by the learned Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak on s 37(da) of the Act. The logic and reasoning for interpreting that subsection in the way in which it was done in Muhammed Hassan appear sufficiently from the judgment in that case. It requires no repetition. All we need say is that para (da) of s 37 is differently constructed from para (d) of that section and must therefore carry a different meaning. As the Act is a penal statute, any ambiguity in language should be resolved in an accused's favour: Sweet v. Parsley [1970] AC 132.

For the foregoing reasons, we reject the argument of the respondent to the effect that Muhammed bin Hassan was wrongly decided and ought no longer to be applied."

[62] In fact, the decision of the Federal Court in Muhammed bin Hassan was also attacked by the prosecution who sought to revisit the ruling on the "double presumption" in subsequent case of PP v. Tan Tatt Eek & Other Appeals [2005] 1 MLRA 58, where, by a majority of 6:1, it was held that there was no valid basis or justification for revisiting Muhammed bin Hassan.

[63] Applying the above guidance, in particular the third reason on the aspect of interpreting the law in Tunde Apatira, we found that the ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau was based on an extensive assessment of the laws - both written and unwritten. And the differences, if any, between the judges in TR Sandah 1 were due to their individual interpretation and construction of the written laws vis-a-vis the unwritten law - the customary law. It is therefore not appropriate for this Court to determine whether or not they interpreted or applied the law correctly, for that is a matter of opinion (Asean Security).

[64] Moreover, the ruling in TR Sandah 1 has been addressed through a legislative intervention by way of amendments made to the Sarawak Land Code in 2018. Such intervention is what the Federal Court in Dalip Bhagwan case had referred to as "the correction of error was normally dependent on the legislative process".

Pemakai Menoa And Pulau Galau - Termed As "Native Territorial Domain" In 2018 Amendments

[65] The appellants argued that Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau - the recognised customs in the 2018 Amendments to the Land Code render TR Sandah 1 as being legally obsolete and overturned.

[66] It was submitted that the amendment to the Sarawak Land Code in 2018 which came into force on 1 August 2019 had the effect of reversing the wrong ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau in TR Sandah 1, hence the need to apply the amendment to these appeals as they have not been finally concluded.

[67] In this regard, the respondents replied that s 6A that was added to the Sarawak Land Code does not apply to the present cases because the appellants in the present appeals have not applied for the said Native Territorial Domain ("NTD").

[68] It was further submitted that NTD under s 6A is an additional claim above a claim for NCR under s 5 of the Sarawak Land Code. Therefore, the 2018 Amendments do not in any way nullify or reverse or overturn TR Sandah 1, nor does it have any retrospective effect, for these cases were filed, heard and decided at the courts below way before its date of in force on 1 August 2019.

[69] The respondents contended that the 2018 Amendments also render the questions seeking to review the ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau in TR Sandah 1 and Nor Ak Nyawai as academic because the amendments clearly recognise these customs as having the force law subject to the requirements and limitations under the said Sarawak Land Code.

[70] It is to be emphasised at the outset that none of the posed questions of law for this court's decision explicitly requires a determination of the effects of the 2018 Amendments to the Sarawak Land Code to TR Sandah 1 or TR Nyutan or Nor Ak Nyawai. Nevertheless, we find that a discussion on the effects of the 2018 Amendments to be inevitable for that legislative move was specifically undertaken in response to the Federal Court's decision in TR Sandah 1 and TR Nyutan. We noted that all relevant parties in these appeals had submitted on the amendments, orally as well as in the written form.

[71] Clearly, one of the objectives of the 2018 Amendments is to statutorily recognise Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau within the scheme of the present SLC, as customs having the force of law in s 6A, but which is termed as Native Territorial Domain for inclusiveness, on which a Native Communal Title in perpetuity will be conferred and be treated as any title granted under the Land Code and the proprietary interest in that title would be indefeasible by virtue s 132 of the SLC.

[72] The key aspects of s 6A, apart from the legal recognition of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau, is the issuance of native communal title in perpetuity, free of any premium, rent or other charges, in the name of a person or body of persons in trust for the native community named therein. And although the claim is limited for up to 500 hectares or 1000 hectares accordingly, the NTD rights exercisable within the NTD may be claimed above and over a NCR under s 5 of the SLC.

[73] The Deputy Chief Minister and Minister for Modernisation Agriculture, Native Land and Regional Development YB Datuk Amar Douglas Uggah Embas, on the second reading of the Land Code (Amendment) Bill, 2018 on 11 July 2018 stated in clear terms the background to the amendment and the objectives it sought to achieve in respect of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau as follows:

"... Tuan Speaker today is a historic moment for the natives of Sarawak. Why? Because we are finally going to see the light of day in respect of native land rights on Pemakai Menoal Pulau Galau territorial domain with the tabling of this amendment bill.

Tuan Speaker, the landmark outcome of this proposed Land Code (Amendment) Bill, 2018 is to enable native communal title in perpetuity to be issued over an area to be described as native territorial domain ...

Tuan Speaker, for the natives of Sarawak, land is regarded as an important part of their livelihood. Their customs and their culture revolve around their lands which are their heritage, passed on or inherited from generation to generation.

Tuan Speaker, more importantly, the natives rely on the land for farming, foraging for food, hunting, fishing and as an important source of materials for domestic purposes. Because of this cultural significance, they have very strong sentiment and attachment to their land.

By adopting the Torrens System for the State's Land Administration System, these cherished customs and practices were not all incorporated into our Land Laws for the creation or acquisition of ownership and proprietary rights to land which the natives have long regarded as their ancestral land. Specifically, our written laws did not expressly stipulate the existence of customs Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau, or the equivalent native territorial domain of other communities and thus this has affected its recognition.

This shortcoming in our laws is manifested in the Judgment of the Federal Court in the case of Director of Forests, Sarawak and State Government of Sarawak v. Tuai Rumah Sandah anak Tabau and 7 Ors, delivered on 20 December 2016. In this case, The Federal Court had ruled that the native customs of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau, although practised by the Iban communities, have no force of law in Sarawak. As a result, the claim by Tuai Rumah Sandah and his anak biaks to ownership rights over land which, according to their own custom, is their Pulau, was dismissed by the Federal Court.

The Federal Court had also ruled that the practice of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau was never recognised to have created customary rights to land by any of the laws passed by or during the Brooke's era or by the State's Legislature. Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau or its equivalent customs of other natives are also not expressly provided for in any of the codified Natives' Adats.

The Federal Court's decision presented the State Government with the opportunity to review the existing laws relating to the acquisition of rights to land based upon the customs of the native communities in Sarawak. Through this review, any legal impediment to all the native communities to lawfully acquire proprietary right in land would be addressed, to meet the expectations of all native communities to get legal recognition of their rights to land acquired in accordance with their own customary laws. The Judgment of the apex Court of this country has a profound impact on the rights of the natives which, in accordance with their customs, is their land. Leaving the Judgment as its stands is not an option ...

The amendments are necessary to give the customs and practices relating to territorial domain, the force of law.

Under the Bill, we use the term native territorial domain instead of Pemakai Menua and Pulau Galau for inclusiveness - because the practice relating to native territorial domain is not only practised by the ibans, but also all other native communities in Sarawak. In the case of Rambli Kawi, Supertindent of Land and Survey, the courts have also recognised the concept of "car/ makan" of the Malay s equivalent to Pemakai Menua and Pulau Galau. Thus, this amendment is inclusive and relevant to all the natives.

Tuan Speaker, it must be noted, although the dissenting judgment of Yang Arif Zainun Ali, in Tuai Rumah Sandah's case gives legal recognition to Pemakai Menua and Pulau Galau, but such right is only limited to usufructuary rights, this means that the natives have the right to only use the resources within the Pulau Galau and Pemakai Menoa for their livelihood but they do not have any legal ownership any propriety rights of the land within those area.

Tuan Speaker, this Land Code (Amendment) Bill, 2018, will not only recognise but also give legal effect to the territorial domain. Clause 2 of the Bill through the definition of "native communal title" expressly provided that a title in perpetuity will be issued in accordance with s 6A over a native territorial domain and that such native communal title shall be held to be a title under the Land Code. This means, that the right under native territorial domain is a statutory proprietary right and not just limited to usufructuary right as recognised under common law and the decision in Tuai Rumah Sandah's case."

[74] Upon perusing s 6A, we are of the opinion that subsection 6 is a crucial provision for it places importance on the date of in force of the amendment - 1 August 2019 and the finality of court's decision in respect of a claim on NTD. Above all else, the customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau have been given statutory recognition, having the force of law, the very crucial element that was found wanting or lacking by the Federal Court decision of TR Sandah 1 and TR Sandah 2 that had denied those customary practices legal enforceability.

[75] This provision prevents a claim for NTD to be made or allowed on any area or land where there is a final decision by a court of competent jurisdiction prior to 1 August 2019. Subsection 6 of s 6A reads as follows:

"(6) Any claim for a native territorial domain shall not be made or allowed in respect of any area or land where, before the coming into force of this section, there is a final decision by a court of competent jurisdiction that no usufructuary rights have subsisted or have been lost or abandoned by members of the native community making that claim."

[76] Considering the background to the 2018 Amendments, with the introduction of s 6A, this provision means that whatever the Federal Court has decided, as a final arbiter, as in TR Sandah 1 or TR Nyutan in respect of the NCR thereof, any claim over those lands or areas concerned shall not be made or allowed, with the coming into force of the 2018 Amendments on 1 August 2019 that statutorily recognised Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau. In other words, subsection 6 of s 6A preserves those disputed area or land in TR Sandah 1 or TR Nyutan from any further claim based on NTD under s 6A.

[77] It also means that a claim for NTD can be made in respect of any area or land where there is no final decision by a court of competent jurisdiction before or after 1 August 2019. The final decision in this provision refers to a decision by the highest court of the land - the Federal Court; and not by the trial High Court or the Court of Appeal, because any decision obtained at these two stages are appealable further rendering their decision as not a 'final decision' within the meaning of s 6A (6). Unless, of course, subject to an important caveat, which is that there was no appeal filed against such decisions so obtained in the lower courts.

[78] Hence, although the 2018 Amendments to the SLC do not contain any express provision to say that those amendments are intended for it to operate retrospectively, the words in s 6A (6) in respect of the NTD provide a "saving" clause to courts' decisions that had been finally decided prior to 1 August 2019, as opposed to those which have not been finally decided, as either pending trial, or appeals which have yet to be finally determined.

[79] The 2018 Amendments have the effect of statutorily overturning the ruling in TR Sandah 1 in respect of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau effectively on 1 August 2019. In other words, the majority ruling on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau in TR Sandah 1 stands as good law from the date of its decision on 20 December 2016 until 31 July 2019. And all final decisions following TR Sandah 1 handed down before 1 August 2019 are, by necessary implication, similarly preserved.

[80] Based on the foregoing deliberations, to revert to the questions of law on the need to review or depart from earlier decision in TR Sandah 1, TR Nyutan; to assess the correctness of the Court of Appeal statement in Nor Ak Nyawai, our answers are as follows.

[81] On the question of law in Case A as to whether it is correct in law or proper for the Court of Appeal to set aside the trial judge's finding of fact based on the application of the decision in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91, our answer is in the affirmative.

[82] It is to be highlighted that when the Court of Appeal heard and decided the appeal on 13 July 2017, it was still legally bound by the principle of stare decisis to follow the ruling of the Federal Court made on 20 December 2016.

We refer specifically to the guidance by the Federal Court in Dalip Bhagwan's case as stated at paragraph [56] of this judgment.

[83] As for the question of law in Case B as to whether the majority decision of Federal Court in Director Of Forest Sarawak & Anor v. TR Sandah Tabau & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 1 SSLR 97; [2017] 2 MLRA 91 with respect to customary practices of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau should be reviewed, and overturned, and Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau restored as customary practices having the force of law, our answer is in the negative based on the reasons stated above at paras [54] to [78]. As explained, Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau are customs having statutory force in the current scheme of a communal title in s 6A of the SLC as opposed to individual title.

[84] As for questions (i) in Case C in respect of the correctness or otherwise of the decision of the Court of Appeal in Nor Ak Nyawai that the rights of the natives is confined to the area where they settled and not where they foraged for food, our answer is in the affirmative for reasons stated at paras [54] to [78] above, in particular that this question has been dealt with quite extensively by this court in TR Sandah 1 which upheld and affirmed the said statement by the Court of Appeal; and so, the same question was posed in Jeli Anak Naga and was answered affirmatively as well. We find there is no valid reason for reviewing or revisiting the correctness or otherwise of the Court of Appeal said decision, especially when this matter has been put to rest by the 2018 Amendments to the SLC, acknowledging Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau as part of legally enforceable NCR.

[85] As a corollary, by answering question (i) of Case C above in the affirmative, the question at (ii) as to whether the alleged practice of the Iban to preserve an area of jungle or forests as Pulau for access for food, wildlife and forest produce, give rise to exclusive rights to the land in the Pulau shall be answered in the negative.

[86] As for the question in Case D which asks whether the Federal Court should depart from the decision of the Federal Court in TR Sandah 1 on the question of Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau having no force of law and that of TR Nyutan on the indefeasibility of the Lease of State Land and if so, whether those cases have any significant bearing on the decision of the Learned Judicial Commissioner in any event, our answer to the first part of the question is in the negative. The reasons are as stated in paras [54] to [78] above. At the risk of repetition, we shall state that those decisions in TR Sandah 1 and TR Nyutan stand as good law as at the date of the pronouncement of those judgments until the date of in force of the 2018 Amendments of the SLC on 1 August 2019.

[87] And effectively, those decisions shall have significant bearing on the decision of the learned Judicial Commissioner at the time of his decision on 17 January 2018. The case of TR Nyutan shall be elaborated further in the later part of this judgment.

[88] At the risk of repetition, when the High Court and the Court of Appeal heard these cases, the legal position on Pemakai Menoa and Pulau Galau and the question of indefeasibility of title and extinguishment (which will be elaborated later) were still governed by the ruling in TR Sandah 1 and TR Nyutan respectively.

[89] Based on the foregoing reasons, on the main question of reviewing or revisiting the case of TR Sandah 1 and TR Nyutan, we find that there is no reason for so departing from those decisions; and hence, the application of these decisions by the courts below, in their decisions which were made prior to the date of in force of the 2018 Amendments to the SLC, was correct and proper as those decisions stand as good law until the legislative intervention which takes effect on 1 August 2019.

TR Nyutan - On Indefeasibility Of Title And Extinguishment Of NCR

[90] Three questions of law relate to the issue of indefeasibility of title and extinguishment of NCR in these appeals. They are Questions 3 and 4 in Case C and part of the question posed in Case D, as follows:

Case C

"(iii) Whether an extinguishment exercise of native customary rights over land as provided under s 15 of the Sarawak Land Code (Cap 81) is required prior to the alienation of lease of state land; and

(iv) If the answer to (iii) is in the affirmative, whether the lease of state land alienated without prior extinguishment of native customary rights is therefore null and void and/or the areas encumbered with native customary rights to be excised out or excluded from the lease of state land."

Case D

"Whether the Federal Court should depart from the decision of the Federal Court in... TH Pelita Sadong Sdn Bhd & Anor v. TR Nyutan Jami & Ors And Other Appeals [2017] 2 SSLR 543; [2017] 6 MLRA 189 on the indefeasibility of the Lease of State Land and if so, whether those cases have any significant bearing on the decision of the Learned Judicial Commissioner in any event?"

What Does TR Nyutan Decide?

[91] The Federal Court in TR Nyutan held that unless there is proof of fraud, "s 132 of the Sarawak Land Code pertaining to indefeasibility of title remains applicable even if it could be shown that NCR had been created over land in the manner prescribed under the same Code. A claim for NCR does not defeat the indefeasibility of title of land, even though the interest stated in the issue document of title was issued after NCR was asserted".

[92] The Federal Court further held that "the proper remedy for the infringement of NCR as a result of the issuance of title or alienation of NCR, where such rights subsist without extinguishment thereof, is an award of damages and not a declaration to nullify the title issued or the rectification of such title issued to third parties".

The Parties' Submissions

[93] It was submitted on behalf of the appellants that alienation of NCR land prior to its legal extinguishment under the Sarawak Land Code is illegal, void and of no effect and consequently the question of indefeasibility of title under s 132 of the SLC does not arise or becomes irrelevant.

[94] It was further claimed that indefeasibility of title can be set aside not only on the basis of fraud but also on grounds of insufficient or void instrument or where the title or interest is unlawfully acquired - based on the clear words of "Subject to this Code" appearing at the opening of s 132. Indefeasibility of title in s 132 must therefore be examined together with other provisions in the SLC.

[95] Hence, TR Nyutan's decision on indefeasibility of title must not only be distinguished due to the factual and contextual differences of that case and the present appeals, but also be overruled for lack of clarity on the "net effect of the principle of indefeasibility" which is subject to certain circumstances, which in the context of the SLC, be subject to other provisions of the SLC - in this case, on the rights of the natives to NCR land.

[96] In this respect, NCR over a land is argued to be an encumbrance on the radical title held by the State, as well as on the title held by a registered proprietor. Therefore, the issuance of a lease does not automatically confer indefeasibility of title if NCR is proven to be within the said lease.

[97] Consequently, where NCR exists, alienation of the land is prohibited until and unless there is prior extinguishment of the said NCR, based on s 15. Furthermore, the SLC does not provide for automatic extinguishment or termination of NCR once a provisional lease is issued. Other provisions were highlighted as conferring statutory protections to NCR. They are ss 4(4), 5(3), 13(1), 15, 18 and 28 of the SLC.

[98] The Respondents on the other hand argued that based on the decision of the Federal Court in Husli Mok v. Superintendent Of Lands & Surveys & Anor [2015] 2 MLRA 195 ("Husli") and TR Nyutan, alienation of the disputed land to third parties had the effect of extinguishing NCR, hence the right to seek for compensation from the State is provided under s 197 of the SLC.

[99] The respondents also cited the case of Mabo and Others v. Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1 to show that at common law, if the sovereign government grants an interest to another party which is inconsistent with the native rights, then this extinguishes the native title for the area concerned.

[100] Moreover, the respondents argued that fraud was never pleaded in these appeals, and as such the registered proprietor held indefeasible title to the land in question.

[101] On the issue of indefeasibility of title, the respondents further submitted that the 2018 Amendments affect provisional lease only and not a lease proper. Therefore, a registered proprietor issued with a lease of State land holds an indefeasible title.

Is NCR A Factor Subjecting Indefeasibility Of Title?

[102] It is undeniable, at first blush, that the argument advanced by the Appellant on the reading of s 132 of the SLC is rather compelling - that what controls indefeasibility of title is not only confined to what has been expressly stated in the said provision - namely, the fraud factor, but also other vitiating factors - such as, the NCR, based on the opening words of s 132 - "Subject to this Code".

[103] Section 132 of the SLC reads:

"(1) Subject to this Code, the registered proprietor of any estate or interest in land to which this section applies shall, except in the case of fraud, hold such estate or interest subject to the interests noted on the Register but free from all other interest except ..."

The Variations Of The Meaning Of Words In The Phrase "Subject To"

[104] The meaning of "subject to" has been defined by the Federal Court in Majlis Agama Islam Wilayah Persekutuan v. Victoria Jayaseele Martin & Another Appeal [2016] 3 MLRA 1 as "conditional or dependent upon something", indicating that the provision containing such words "does not stand alone on its own and must not be read on its own". Hence, the words in the phrase "subject to" must be a factor to be considered in interpreting any section in a statute, in the context of that case, the term "subject to" in the beginning of s 59(1) of the Administration of Islamic Law (Federal Territories) Act 1993 is not merely an enabler, but is an important part of the provision which may determine the manner in which the provision is to be read and construed.

[105] In Government Of The Federation Of Malaya v. Surinder Singh Kanda [1960] 1 MLRA 458, the main issue relates to the construction of the meaning of "subject to the provisions of any existing law" in art 140(1) of the Federal Constitution and "Subject to the provisions of any existing law and to the provisions of this Constitution" in art 144(1) of the Federal Constitution. Thomson CJ considered the words "subject to" as words of limitation or restriction in conformity with what was said in Smith v. London Transport Executive [1951] AC 555 565; [1951] 1 All ER 667 where Lord Simonds stated that the words "are apt to enact that the powers thereafter given are subject to restrictions or limitations to be found elsewhere". His Lordship further said:

"The words 'subject to the provisions of this Act'... are naturally words of restriction. They assume an authority immediately given and give a warning that elsewhere a limitation upon that authority will be found."

[106] Neal J (dissenting) in his endeavor to ascertain the meaning of the words "subject to", found that the words are given not one meaning but varied meanings. We reproduce below what Neal J had thereby stated, like so: