Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Vazeer Alam Mydin Meera, Abu Bakar Jais, Darryl Goon Siew Chye JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: W-01(A)-77-02-2020]

14 January 2022

Constitutional Law: Public servants - Pension - Validity of amendments to ss 3 and 6 Pensions Adjustment Act 1980 - Whether amendments in contravention of art 147 Federal Constitution - Whether amendments resulted in less favourable situation to pensioners - Whether remedy provided by amending provision - Whether term "may" in amending provision did not ensure that constitutional guarantee provided by art 147 would not be contravened - Whether amendments rendered null and void - Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013, ss 3, 7

Statutory Interpretation: Amending legislation - Validity of - Sections 3 and 7 Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013 - Whether amendments resulted in less favourable situation to pensioners in contravention of art 147 Federal Constitution - Whether remedy provided by amending provision - Whether term "may" in amending provision did not ensure that constitutional guarantee provided by art 147 would not be contravened - Whether amendments rendered null and void - Pensions Adjustment Act 1980, ss 3, 6

Civil Procedure: Judgments and orders - Date when judgment became effective - Amendments to Pensions Adjustment Act 1980 declared null and void - Consequential repercussions on pensioners as a result thereof - Whether doctrine of prospective overruling applicable to mitigate repercussions - Whether judgment to take effect prospectively - Whether effective date was when judgment made - Pensions Adjustment Act 1980, ss 3, 6 - Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013, ss 3, 7 - Federal Constitution, art 147

This appeal stemmed from the appellant's action challenging the validity of certain amendments to the Pensions Adjustment Act 1980 ('PAA'). She brought the action on behalf of herself and on behalf of 56 retirees from the public services. She claimed that ss 3 and 6 PAA amended by ss 3 and 7 of the Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013 ('the 2013 Amendment Act') contravened art 147 of the Federal Constitution ('art 147 of the Constitution') resulting in a situation less favourable to her and the 56 retirees she represented. Prior to the amendments, pensions were adjusted whenever there was a revision or adjustment of salary for serving government employees. However, the amendments, which introduced an annual increment of 2%, resulted in a less favourable outcome. Against this, the respondents claimed that the 2013 Amendment Act brought about adjustments for the benefit and welfare of pensioners without having to wait for any salary revision in the civil service and hence the 2% annual increment. Further, should a less favourable outcome arise, the amendments provided a remedy wherein the Yang di-Pertuan Agong might prescribe different percentages of increment for different categories of recipients. The learned judge dismissed the appellant's action and the appellant now appealed.

Held (allowing the appeal):

(1) The amended s 3(2) PAA acknowledged that a less favourable situation could arise and built in a mechanism to address it ie that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong "... may by order in the Gazette prescribe an appropriate higher percentage of increment to be applied in such case". However, the term "may" imposed no obligation to act and was merely permissive. It could not be read as "shall". As such, an adjustment that would have occurred as of right under the PAA before the amendment was reduced to something that might only be acted upon by reason of the 2013 Amendment Act. That did not ensure that the constitutional guarantee provided by art 147 of the Constitution could not be contravened. Article 147 could not be contravened if it was stipulated that the adjustment was to be made automatically or that it should be implemented as of right to extinguish the less favourable situation, which was not the case here. (paras 29, 32, 33 & 34)

(2) The appellant or the pensioners she represented need not suffer actual loss or damage before art 147 of the Constitution was contravened. The existence of a risk of a less favourable situation and the mere possibility of it was sufficient to establish that a less favourable situation had come about. As such, the appellant and the pensioners she represented, or any pensioner affected by the impugned amendments, might seek the reliefs sought. The risk of a less favourable situation arising did not exist prior to the amendments brought about by the 2013 Amendment Act. That such a risk now existed with the amendments, when it did not before was in itself a less favourable situation. There was no certainty that the risk of a less favourable situation would be remedied under the amended s 3(2) PAA. The less favourable situation might persist and might not be remedied. Such would not have existed under the PAA prior to the amendments. (paras 35-37)

(3) Article 147 of the Constitution stipulated that it was the "later law" that must not be "less favourable". There was no requirement that a pensioner must first suffer actual loss or damage before the less favourable law might be held to contravene art 147. The protection afforded to pensioners from the public services against any subsequent and less favourable law was embodied in the Federal Constitution. That protection must therefore be accorded the importance and gravity equal to the Federal Constitution itself. (paras 38 & 40)

(4) The amendments to s 3 and s 6 PAA brought about by s 3 and s 7 of the 2013 Amendment Act contravened art 147 of the Constitution. Accordingly, s 3 and s 7 of the 2013 Amendment Act were void. The impugned amendments were not ultra vires art 147 as stated by the appellant in the declarations she sought but were in contravention of art 147 and void by reason of art 4(1) of the same. The respondents were not misled in any way as to the precise issue involved in this case ie the validity of the impugned amendments. (paras 41-45)

(5) The situation prevailing before the amendment to s 3 PAA would be revived and continued to apply. However, there was no order for retrospective adjustments to be made to pensions paid and for any shortfall to be paid to the appellant on the ground that the appellant did not prove she suffered any actual loss. No specific mention was made on this issue in the Memorandum of Appeal or in the appellant's written and oral submissions. (paras 48-49)

(6) The doctrine of prospective overruling was applicable to mitigate the adverse consequences and hardship the decision of this court might have on pensioners. As such, this decision was only to take effect prospectively from the date it was made ie 13 January 2022. However, it would have effect on any pending proceedings, whether pending at first instance or pending appeal, in respect of issues relating to the declarations made herein. Further too, provisions dependent on the impugned sections were declared null and void and accordingly ineffective and unenforceable. (paras 50, 59, 60 & 61)

Case(s) referred to:

Abillah Labo Khan v. PP [2002] 1 MLRA 294 (refd)

Cadder v. Her Majesty's Advocate [2010] UKSC 43 (refd)

Chintaman Rao v. The State Of Madhya Pradesh [1950] SCR 594 (folld)

Dato' Menteri Othman Baginda & Anor v. Dato' Ombi Syed Alwi Syed Idrus [1980] 1 MLRA 18 (refd)

Datuk Raja Ahmad Zainuddin Raja Omar v. Perbadanan Kemajuan Iktisad Negeri Kelantan [2014] 3 MLRA 460 (refd)

Golak Nath v. State Of Punjab [1967] AIR 1643 (SC) (folld)

Haji Wan Othman & Ors v. Government Of The Federation Of Malaya [1966] 1 MLRA 625 (refd)

L Capital Jones Ltd And Another v. Maniach Pte Ltd [2017] 1 SLR 312 (folld)

Letchumanan Chettiar Alagappan @ L Allagappan & Anor v. Secure Plantation Sdn Bhd [2017] 3 MLRA 501 (refd)

Ling Peek Hoe & Anor v. Ding Siew Ching & Another Appeal [2017] 4 MLRA 372 (folld)

Majlis Agama Islam Selangor v. Bong Boon Chuen & Ors [2009] 2 MLRA 453 (refd)

Mamat Daud & Ors v. The Government Of Malaysia [1987] 1 MLRA 292 (folld)

Mohammed v. The State [1999] 2 AC 111 (refd)

N R Sundararaj v. Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Perkhidmatan Awam Malaysia & Anor [1993] 1 MLRH 68 (refd)

PP v. Hue An Li [2014] 4 SLR 661 (folld)

PP v. Mohd Radzi Abu Bakar [2005] 2 MLRA 590 (refd)

Public Prosecutor v. Dato' Yap Peng [1987] 1 MLRA 103 (refd)

Public Prosecutor v. Manogaran S/O Ramu [1997] 1 SLR 22 (folld)

R Rama Chandran v. Industrial Court Of Malaysia & Anor [1996] 1 MELR 71; [1996] 1 MLRA 725 (refd)

Re Spectrum Plus Ltd National Westminster Bank Plc v. Spectrum Plus Ltd And Others [2005] UKHL 41 (folld)

Repco Holdings Bhd v. PP [1997] 3 MLRH 304 (folld)

Sarwan Kumar v. Madan Lal Aggrawal[2003] AIR 1475 (SC) (folld)

Tan Tek Seng v. Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan & Anor [1996] 1 MLRA 186 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Criminal Procedure Code, s 418A

Federal Constitution, arts 4(1), 121(1), 147(1)

Penal Code, s 298A

Pensions Adjustment Act 1980, ss 2, 3(1), (2), 3A(1), 3A(2)(a), 3A(2)(b), 3A(3), 3B, 6, 7

Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013, ss 3, 7

Securities Commission Malaysia Act 1993, s 39(2)

Securities Industry Act 1983, s 129(2)

Counsel:

For the appellant: Gopal Sri Ram (Lim Choon Khim, Chin Yan Leng, How Li Nee & Marcus Lee with him); M/s CK Lim Law Chambers

For the respondents: Shamsul Bol Hassan (Liew Horng Bin & Kogilambigai Muthusamy with him); AG's Chambers

JUDGMENT

Darryl Goon Siew Chye JCA:

[1] This appeal concerns the validity of certain amendments made to the Pensions Adjustment Act 1980 ("PAA 1980").

[2] The challenge to the validity of the amendments in question was premised squarely upon art 147 of the Federal Constitution. This was a challenge brought by the appellant on her own behalf and on behalf of fifty-six retirees from the public services.

[3] In essence, it was the appellant's contention that the amendments to ss 3 and 6 of the PAA 1980, brought about by ss 3 and 7 of the Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013 ("2013 Amendment Act"), contravenes art 147 of the Federal Constitution. 626 627

[4] This is the judgment of the Court.

[5] Article 147 of the Federal Constitution states as follows:

"Protection of pension rights

147. (1) The law applicable to any pension gratuity or other like allowance (in this Article referred to as an "award") granted to a member of any of the public services, or to his widow, children, dependant or personal representatives, shall be that in force on the relevant day or any later law not less favourable to the person to whom the award is made.

(2) For the purposes of this Article the relevant day is-

(a) in relation to an award made before Merdeka Day, the date on which the award was made;

(b) in relation to an award made after Merdeka Day to or in respect of any person who was a member of any of the public services before Merdeka Day, the thirtieth day of August, nineteen hundred and fifty-seven;

(c) in relation to an award made to or in respect of any person who first became a member of any of the public services on or after Merdeka Day, the date on which he first became such a member.

(3) For the purposes of this Article, where the law applicable to an award depends on the option of the person to whom it is made, the law for which he opts shall be taken to be more favourable to him than any other law for which he might have opted."

[Emphasis Added]

[6] The appellant's contention was that the amendments brought about by the 2013 Amendment Act resulted in a situation "less favourable" to the appellant when compared with the preceding retirement adjustment scheme under the PAA 1980, prior to the amendments. This, it was contended, contravened art 147(1) of the Federal Constitution.

PAA 1980 Prior To The 2013 Amendment Act

[7] Prior to the 2013 Amendment Act, s 3 of the PAA 1980 provided as follows:

"Adjustment of pensions and other benefits of officers and dependants

3.(1) Pensions and other benefits granted to officers and their dependants under any written law before or on the implementation of any current salary scale shall be adjusted in accordance with the provisions of this Act and shall be paid or be payable with effect from the date of implementation of the current salary scale.

(2) The pension or retiring allowance of an officer shall be adjusted as provided in the First Schedule."

[Emphasis Added]

[8] Section 2 of the PAA 1980, provided that:

"'current salary scale' means the latest scale which is, on or after the coming into force of this Act, applicable to officers of the public service and employees of statutory and local authorities to whom the revision of salaries made by the Federal Government with effect from 1 January 1976, or any other subsequent revision thereof made by the Federal Government from time to time, is applicable;"

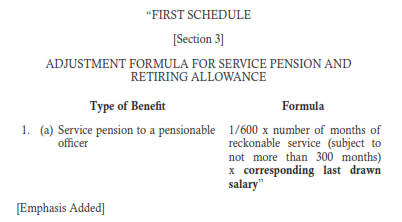

[9] The relevant portion of the First Schedule referred to in s 3(2) provided as follows:

[10] Section 2 of the PAA 1980, provided that:

"'Corresponding last drawn salary' means the corresponding last drawn salary as defined under subsection 6(2)."

[11] Prior to the 2013 Amendment Act, ss 6 of the PAA 1980 provided as follows:

"Determination of corresponding last drawn salary

6. (1) The Director General shall determine the corresponding last drawn salary of an officer.

(2) For the purposes of this Act, "corresponding last drawn salary" means, in the case of an officer to whom the current salary scale does not apply by virtue of:

(a) his not having had an opportunity to opt;

(b) his not having opted; or

(c) his not being deemed to have opted,

for the current salary scale, the equivalent salary that the officer would have drawn under the current salary scale prior to death in service or to retirement had he been in service on the implementation of the current salary scale and had it been applied to him."

[Emphasis Added]

[12] What is relevant to note for the purposes of this case is that pensions under the PAA 1980, prior to the 2013 Amendment Act, were adjusted whenever there was a revision or adjustment of salary for serving government employees in the public services.

The Impugned Amendments

[13] Section 3 of the PAA 1980 was amended by s 3 of the 2013 Amendment Act. Section 7 of the 2013 Amendment Act amended s 6 of the PAA 1980 by deleting s 6 altogether. These amendments came into effect on 1 January 2013.

[14] Section 3 of the PAA 1980 was substituted with the following:

"Adjustment of pensions and other benefits of officers and dependants

3. (1) Pensions and other benefits granted to officers and their dependants under any written law shall be adjusted annually by an increment of two percent in accordance with the provisions of this Act and shall be paid or be payable with effect from January of each year.

(2) Notwithstanding subsection (1), where the application of the specified rate of increment would result in a situation that is less favourable to an officer appointed before the coming into force of this section, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong may by order in the Gazette prescribe an appropriate higher percentage of increment to be applied in such case.

(3) For the purpose of an order under subsection (2), the Yang di-Pertuan Agong may prescribe:

(a) different percentages of increment for different categories of recipients:

(b) that the higher percentage of increment shall only apply for a specified year or any part thereof, and in such case, the date on which the adjustment shall be payable."

[15] New ss 3A and 3B were added to the amended s 3 of the PAA 1980 and they were as follows:

"Adjustments of pensions, disability pensions, retiring allowances or injury allowances

3A. (1) Pensions, disability pensions, retiring allowances or injury allowances received by an officer under any written law shall be adjusted in accordance with subsection 3(1).

(2) The amount of pension, disability pension, retiring allowance or injury allowance to be used as the basis for the first of the adjustments under subsection 3(1):

(a) in the case of an officer who retired before or on 1 January 2012, shall be the amount of pension, disability pension, retiring allowance or injury allowance which had been adjusted on that date;

(b) in the case of an officer who retired on or after 2 January 2012, shall be the amount of pension, disability pension, retiring allowance or injury allowance which had been granted to the officer.

(3) The adjustment referred to in subsection (1) is subject to any higher percentage of increment which may be made under subsection 3(2).

Adjustment of lowest pension and other benefits

3B. Where an officer is receiving the lowest amount of pension or other benefit payable pursuant to s 8, the said lowest amount shall be used as the basis for the first of the adjustments under subsection 3(1)."

[16] The amendments introduced also deleted the definition of the term "corresponding last drawn salary" under s 2 of the PAA 1980.

[17] As can be seen, instead of the previous scheme, the amended s 3(1) introduced a new method of adjusting pensions and other benefits by means of an annual increment of two percent payable from January of each year.

[18] In addition, the new s 3(2) provided a mechanism for an adjustment should the annual rate of increment result in a situation less favourable to an officer appointed before the coming into force of the amended s 3.

Article 147 Of The Federal Constitution

[19] The appellant is a pensioner having retired as a civil servant with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in September 2002, where she had served for over thirty-three years.

[20] The appellant and the fifty-six pensioners she represents had, upon their retirement, been receiving their pensions in accordance with the provisions under the PAA 1980, before it was amended by the 2013 Amendment Act.

[21] The appellant contended that the amendments introduced through ss 3 and 7 of the 2013 Amendment Act had resulted in a situation less favourable' to her and the fifty-six pensioners she represents, when compared with their position under the PAA 1980, prior to the 2013 Amendment Act.

[22] It was contended by the appellant in her affidavit that the PAA 1980, before its amendment, had "... introduced a new two pronged principle that pensions be adjusted on current salaries and intricately linked to their respective grade and rank in the civil service. This gave the pensioners an assurance of enjoying a continuous pension of comparable amounts to those retired subsequently on similar grades and rank.". 630 631

[23] Calculations were also presented by the appellant in her affidavit to demonstrate how a less favourable outcome had occurred. This was disputed by the respondents. The calculations provided by the appellant were found to be incorrect by the learned Judge. The respondents maintained that the 2013 Amendment Act, as a matter of fact, had not actually resulted in any less favourable a situation for the retirees.

[24] The respondents' contention was that the 2013 Amendment Act was introduced for the benefit of the retirees. It was conceded that the pre-amended PAA 1980 had provided for adjustments to pensions. However, it was contended that the 2013 Amendment Act brought about adjustments "for the benefit and welfare of pensioners and their dependents without having to wait for any salary revision in the civil service. Hence, the Amended Act which gives an increment of 2% annually".

[25] It was submitted on behalf of the Respondents that the intention of the 2013 Amendment Act was to benefit retirees and this was made clear by the explanation given by the Timbalan Menteri di Jabatan Perdana Menteri, Datuk Liew Vui Keong, in Parliament on 27 November 2012, recorded in the Hansard, relevant excerpts of which are reproduced below:

"Timbalan Menteri di Jabatan Perdana Menteri [Datuk Liew Vui Keong]: Tuan Yang di-Pertua, saya memohon mencadangkan supaya rang undang-undang bernama Akta Penyelerasan Pencen (Pindaan) 2012 dibaca kali yang kedua sekarang.

Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Akta Penyelerasan Pencen 1980 [Akta 238] ialah undang-undang yang mentadbir urusan penyelerasan pencen dan faedah persaraan lain bagi pesara Perkhidmatan Awam Persekutuan dan negeri serta pesara pihak berkuasa berkanun dan tempatan apabila berlakunya semakan gaji anggota sector awam.

Tuan Yang di-Pertua, tujuan pindaan yang dicadangkan adalah bagi menggantikan cara penyelerasan pencen sedia ada dengan satu kaedah baru yang lebih baik mengambil kira perubahan-perubahan terkini dalam prinsip dan struktur gaji sector awam di samping menjaga kebajikan penerima pencen

...

Tuan Yang di-Pertua, sudah tiba masanya system penyelarasan pencen yang telah pun memberikan kebaikan kepada pesara setelah sekian lama dipinda sesuai dengan perkembangan tersebut. Untuk menangani perubahan-perubahan yang berlaku ini, kita perlu menetapkan satu kadar bagi penyelerasan pencen yang tidak lagi bergantung pada semakan gaji berasaskan gaji bersamaan yang akhir diterima. Cara yang dicadangkan adalah kenaikan pencen sebanyak 2 peratus setiap tahun untuk semua anggota penerima pencen yang berkuatkuasa mulai 1 Januari 2013.

Cara penyelarasan yang dicadangkan ini akan memberikan manfaat kepada semua pesara yang bukan sahaja di kalangan pesara perkhidmatan awam persekutuan malahan termasuk juga pesara perkhidmatan awam negeri serta perkhidmatan berkuasa berkanun dan tempatan di negeri-negeri. Pencen bagi semua golongan ini dibiayai sepenuhnya oleh Kerajaan Persekutuan.

Tuan Yang di-Pertua, antara keluhan pesara dan penerima pencen pada masa ini ialah mereka terpaksa menunggu semakan gaji anggota sektor awam untuk mendapat kenaikan pencen. Semakan gaji ini biasanya dibuat dalam tempoh lima tahun. Sebaliknya, cara penyelarasan yang dicadangkan ini membolehkan pesara menikmati kenaikan pencen setiap tahun. Contohnya seseorang pesara yang menerima pencen RM1,000 pada penghujung 2012, pada 1 Januari 2013 pencennya akan meningkat kepada RM1,020. Pada 1 Januari 2014 pencennya akan meningkat kepada RM1,040.40 dan pada 1 Januari 2015 pencennya akan meningkat kepada RM1,061.20. Penyelarasan pencen setiap tahun ini untuk seumur hidup diharap dapat membantu pesara menampung kos sara hidup yang semakin meningkat dari semasa ke semasa yang disebabkan oleh inflasi.

Tuan Yang di-Pertua, adalah diakui pada masa kini pesara tidak boleh membuat perancangan kewangan mereka kerana tidak mengetahui bila dan berapa kadar kenaikan pencen mereka. Dengan pindaan yang dicadangkan ini kadar kenaikan pencen tahunan dimaktubkan dalam Undang-Undang Penyelarasan Pencen. Pelaksanaan cadangan ini akan menceriakan semua pesara sektor awam.

Tuan Yang di-Pertua, ini adalah satu hadiah daripada kerajaan yang prihatin serta mengenang bagi menghargai jasa-jasa pesara yang telah memberikan sumbangan bakti kepada negara semasa mereka berkhidmat dahulu. Bagi pegawai yang sedang berkhidmat pula, anggaplah penambahbaikan ini sebagai satu dorongan untuk terus berkhidmat secara produktif dan menyampaikan perkhidmatan dengan lebih cemerlang demi kesejahteraan rakyat. Tuan Yang di-Pertua, saya mohon mencadangkan."

[26] It was contended that the annual two per cent increment brought about by the 2013 Amendment Act cannot be said to be a less favourable pension adjustment. In addition, it was pointed out that the amended s 3(2) addresses a less favourable outcome, should it present. Should the annual two per cent increment result in a situation less favourable to an officer, an application may be made and the Yang di-Pertuan Agong may prescribe different percentages of increment for different categories of recipients to remedy the situation.

Was Article 147 Of The Federal Constitution Contravened?

[27] In resisting the appellant's contentions, the learned Senior Federal Counsel for the Respondents maintained that there is no right to a pension, citing Haji Wan Othman & Ors v. Government Of The Federation Of Malaya [1966] 1 MLRA 625. Also cited was the decision in N R Sundararaj v. Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Perkhidmatan Awam Malaysia & Anor [1993] 1 MLRH 68, where Abu Mansor J stated as follows:

"A case directly on point is the cited case of Haji Wan Othman & Ors v. Government Of The Federation Of Malaya [1966] 1 MLRA 625, where it was held that the whole tenor of the pensions legislation is permissive and no officer has therefore an absolute right to pension."

[28] However, we are not here concerned with a claim to an entitlement to pension not granted. The issue at hand is a narrow one. It is whether the amendments to ss 3 and 6 of the PAA 1980 contravenes art 147 of the Federal Constitution. It is whether the law applicable to pensions granted to members of the public services has somehow been rendered less favourable.

[29] The respondents and the learned Judge recognise that the amended s 3(2) of the PAA 1980 acknowledges that a less favourable situation could arise. At paras [30] and [32] of the learned Judge's judgment, it was stated thus:

"[30] It is clear to me on reading the amended subsections 3(1), 3(2) and 3(3) in its entirety together with the new subsections 3A(1), 3A(2)(a), 3A(2)(b) and 3A(3) that Parliament was aware that the amendment from the variable rate of pension adjustment pegged to the latest revision of the applicable salary scale to a fixed rate adjusted of two (2%) per cent per annum could result in certain pensioners or their widows, children, dependents or personal representatives being put in a position that is less favourable from their position prior to the amendments in the PAA 1980 coming into effect.

[32] Therefore in order to ensure that the constitutional guarantee enshrined in art 147 of the Federal Constitution is preserved and to protect against the likelihood of situations where pensioners or their widow, children, dependants or personal representatives are put in a less favourable position because of the change to the annual fixed rate pension adjustment, Parliament expressly provided a safeguard in subsection 3(2) of the PAA 1980."

[30] But does the amended s 3(2) of the PAA 1980 ensure that the constitutional guarantee in art 147 of the Federal Constitution is preserved? With respect, we do not think so.

[31] The amended s 3(2) of the PAA 1980, as was quite rightly pointed out, caters for a situation where the annual two per cent increment may result in a situation less favourable than under the PAA 1980, prior to its amendment.

[32] In our view, the amended s 3(2) of the PAA 1980 is in fact an acknowledgement that the amendments could result in a less favourable situation. On this, we are in agreement with the learned Judge. However, the mechanism built into s 3(2) to address a less favourable situation, should it arise, is merely permissive. This is because what is clearly stated is that should a less favourable situation materialise, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong "... may by order in the Gazette prescribe an appropriate higher percentage of increment to be applied in such case" [Emphasis Added].

[33] It is plainly obvious that the term "may", in s 3(2) of the PAA 1980 as amended, imposes no obligation to act. "May" is merely permissive (see Datuk Raja Ahmad Zainuddin Raja Omar v. Perbadanan Kemajuan Iktisad Negeri Kelantan [2014] 3 MLRA 460 at para 14). In context, it simply cannot be read as "shall" and there is also no submission by the respondents to this effect. It is evident that the word "may" is here used in contradistinction to the word "shall". This is not a case that admits of more than one possible interpretation. Thus, what would have been an adjustment that would have occurred as of right under the PAA 1980 before its amendment, is, by reason of the 2013 Amendment Act, reduced to something that may be acted upon in the manner provided by the amendments.

[34] In our view, the amended s 3(2) of the PAA 1980 does not ensure that art 147 of the Federal Constitution is not contravened. It would have been so if, should a less favourable situation arise, the machinery provided for adjustment under the amended s 3(2) were to be implemented automatically or that it shall be so implemented as of right, to extinguish the less favourable situation.

[35] Must the appellant or the pensioners she represents suffer actual loss or damage before it may be contended that art 147 of the Federal Constitution is contravened? We think not. The existence of a risk that a less favourable situation might arise and the mere possibility that it can arise, which is an acknowledgment inherent in s 3(2) as amended, suffices in establishing that a less favourable situation has indeed, already come about. As such, the appellant and the pensioners she represents, or for that matter any pensioner who may be affected by the impugned amendments, may seek the reliefs sought.

[36] The risk of a less favourable situation arising never existed prior to the amendments brought about by the 2013 Amendment Act. That such a risk now exists with the amendments, when it never did before is, in our view, in itself a less favourable situation. A similar rationale was expressed by the Supreme Court of India in Chintaman Rao v. The State Of Madhya Pradesh [1950] SCR 594 at p 765, where Mahajan J stated:

"The law even to the extent that it could be said to authorize the imposition of restrictions in regard to agricultural labour cannot be held valid because the language employed is wide enough to cover restrictions both within and without the limits of constitutionally permissible legislative action affecting the right. So long as the possibility of its being applied for purposes not sanctioned by the Constitution cannot be ruled out, it must be held to be wholly void."

[Emphasis Added]

[37] Should the risk materialise, and a less favourable situation actually presents, with actual loss suffered by pensioners, there is no certainty that the situation presented will be remedied under the amended s 3(2). The less favourable situation may persist and may never be remedied. Such, would not have existed under the PAA 1980, prior to the amendments.

[38] Under art 147 of the Federal Constitution, it is the 'later law' that must not be 'less favourable'. There is no requirement that any pensioner, for example, must first suffer actual loss or damage before the less favourable law may be held to contravene art 147.

[39] As was pointed out in the decision of the Federal Court in Dato' Menteri Othman Baginda & Anor v. Dato' Ombi Syed Alwi Syed Idrus [1980] 1 MLRA 18, by Raja Azlan Shah Ag LP (as His Royal Highness then was):

"In interpreting a constitution two points must be borne in mind. First, judicial precedent plays a lesser part than is normal in matters of ordinary statutory interpretation. Secondly, a constitution, being a living piece of legislation, its provisions must be construed broadly and not in a pedantic way - "with less rigidity and more generosity than other Acts" (see Minister Of Home Affairs v. Fisher [1979] 3 All ER 21. A constitution is sui generis, calling for its own principles of interpretation, suitable to its character, but without necessarily accepting the ordinary rules and presumptions of statutory interpretation."

[40] It is singularly significant that the protection afforded to pensioners from the public services against any subsequent and less favourable law is embodied in the Federal Constitution. That protection must therefore be accorded the importance and gravity equal to the Federal Constitution itself. As Lord Steyn observed in the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Mohammed v. The State [1999] 2 AC 111, 123:

"It will be recalled that in King v. The Queen [1969] 1 AC 304, 319, Lord Hodson observed that it matters not whether the right infringed is enshrined in a constitution or is simply a common law right (or presumably an ordinary statutory right). Their Lordships are satisfied that in King v. the Queen, which was decided in 1968, the Board took too narrow a view on this point. It is a matter of fundamental importance that a right has been considered important enough by the people of Trinidad and Tobago, through their representatives, to be enshrined in their Constitution. The stamp of constitutionality on a citizen's rights is not meaningless: it is clear testimony that an added value is attached to the protection of the right."

[Emphasis Added]

[41] We are therefore of the view that the amendments to s 3 and 6 of the PAA 1980 brought about by ss 3 and 7 of the 2013 Amendment Act contravene art 147 of the Federal Constitution.

[42] Article 4(1) of the Federal Constitution provides as follows:

"4.(1) This Constitution is the supreme law of the Federation and any law passed after Merdeka Day which is inconsistent with this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void."

[43] Accordingly, we hold ss 3 and 7 of the 2013 Amendment Act to be inconsistent with art 147 of the Federal Constitution and therefore void.

[44] The declarations sought by the appellant were predicated on a contention that the impugned amendments are ultra vires art 147 of the Federal Constitution. We do not think this is a case of the impugned amendments being ultra vires. Rather, it is a case of the impugned amendments being in contravention of art 147 of the Federal Constitution and are accordingly void by reason of art 4(1).

[45] Clearly, the respondents would not have been misled in any way as to the precise issue involved in this case ie the validity of the impugned amendments.

[46] We are satisfied that the Court has the power to mould the relief to be given including, in this case, the appropriate declaration to be made (see Tan Tek Seng v. Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan & Anor [1996] 1 MLRA 186; R Rama Chandran v. Industrial Court Of Malaysia & Anor [1996] 1 MELR 71; [1996] 1 MLRA 725; Majlis Agama Islam Selangor v. Bong Boon Chuen & Ors [2009] 2 MLRA 453).

[47] Accordingly, we make the following declarations:

i. A declaration that ss 3 and 7 of the Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013 are null and void being in contravention of art 147 of the Federal Constitution;

ii. A declaration that ss 3 and 6 of the Pensions Adjustment Act 1980 as amended by ss 3 and 7 of the Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013 and in force since 1 January 2013 are null and void being in contravention of art 147 of the Federal Constitution;

[48] In substance these declarations are not inconsistent with the actual declarations sought. With these declarations, the situation prevailing before the amendment to s 3 of the PAA 1980 will be revived and continue to apply.

[49] We however, decline to make any order for retrospective adjustments to be made to pensions paid and for any shortfall to be paid to the appellant on the ground that it has not been proven that any actual loss has been suffered by the appellant. This was the finding of fact by the learned Judge and in respect of which we find no appealable error. In addition, no specific mention was made of this issue in the Memorandum of Appeal and this issue was not submitted on by learned counsel for the appellant; neither in his written submissions nor his oral submissions.

[50] The court however, is cognisant of the consequential repercussions that its decision and the declarations made will have on pensioners who have received a two per cent annual increment pursuant to the amendments now declared null and void. It may be that they may have to refund amounts that they have received as pensions that might be more than they would have received under the former scheme before the amendments. This is therefore a decision that can have disruptive, burdensome and even oppressive consequences for such pensioners who may hitherto have no idea that the two per cent that they had been receiving may have to be refunded by reason of this court's decision.

[51] The general common law principle is that the decision of a court on a point of law is declaratory in nature. Courts declare what is and what has always been the law and it would thus have both retrospective and prospective effect as well. As was stated in the decision of this court in Abillah Labo Khan v. PP [2002] 1 MLRA 294, 'It is a fundamental principle of adjudicative jurisprudence that all judgments of a court are retrospective in effect'. However, the law has evolved to afford Courts, in appropriate cases, with a discretion to mitigate foreseeable adverse consequences and hardship, especially if it would otherwise affect a class of the citizenry. This may sometimes be achieved by invoking the doctrine of 'prospective overruling'; a ruling that is to be effective only prospectively. As Lord Nicholls described it in Re Spectrum Plus Ltd National Westminster Bank Plc v. Spectrum Plus Ltd And Others [2005] UKHL 41:

"'Prospective overruling', sometimes described as 'non-retroactive overruling', is a judicial tool fashioned to mitigate these adverse consequences. It is a shorthand description for court rulings on points of law which, to greater or lesser extent, are designed not to have the normal retrospective effect of judicial decisions."

Lord Nicholls, was prepared to countenance the adoption of the doctrine but found no justification to do so in the case itself. Lord Nicholls was however, prepared to adopt a 'never say never' approach which was an approach that met with the approval of the other judges in the case (see also Cadder v. Her Majesty's Advocate [2010] UKSC 43).

[52] This doctrine of prospective overruling was adopted and applied by the Supreme Court over 30 years ago in Public Prosecutor v. Dato' Yap Peng [1987] 1 MLRA 103, when, by a majority, the Supreme Court held s 418A of the Criminal Procedure Code to be unconstitutional and void, as being an infringement of art 121(1) of the Federal Constitution. As Abdoolcader SCJ pointed out in that case:

"The general principle of retroactivity of a judicial declaration of invalidity of a law was overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States of America in Linkletter v. Walker (at p 628) when it devised the doctrine of prospective overruling in the constitutional sphere in 1965 as a practical solution for alleviating the inconveniences which would result from its decision declaring law to be unconstitutional, after overruling its previous decision upholding its constitutionality. The doctrine was applied by the Supreme Court of India in LC Golak Nath v. State Of Punjab & Anor (at pp 1666-1669). The doctrine - to the effect that when a statute is held to be unconstitutional, after overruling a long-standing current of decisions to the contrary, the Court will not give retrospective effect to the declaration of unconstitutionality so as to set aside proceedings of convictions or acquittals which had taken place under that statute prior to the date of the judgment which declared it to be unconstitutional, and convictions or acquittals secured as a result of the application of the impugned statute previously will accordingly not be disturbed - can be applied by the Supreme Court as the highest court of the country in a matter arising under the constitution to give such retroactive effect to its decision as it thinks fit to be moulded in accordance with the justice of the cause or matter before it - to be adhibited however with circumspection and as an exceptional measure in the light of the circumstances under consideration."

See also the discussion of this doctrine in PP v. Mohd Radzi Abu Bakar [2005] 2 MLRA 590 and Letchumanan Chettiar Alagappan @ L Allagappan & Anor v. Secure Plantation Sdn Bhd [2017] 3 MLRA 501, FC.

[53] In Golak Nath v. State Of Punjab [1967] AIR 1643 (SC), the Supreme Court of India explained as follows:

"(47) Let us consider some of the objections to this doctrine. The objections are: (1) the doctrine involved legislation by courts; (2) it would not encourage parties to prefer appeals as they would not get any benefit therefrom; (3) the declaration for the future would only be obiter; (4) it is not a desirable change; and (5) the doctrine of retroactivity serves as a break on courts which otherwise might be tempted to be so facile in overruling. But in our view, these objections are not insurmountable. If a court can overrule its earlier decision - there cannot be any dispute now that the court can do so - there cannot be any valid reason why it should not restrict its ruling to the future and not to the past. Even if the party filing an appeal may not be benefited by it, in similar appeals which he may file after the change in the law he will have the benefit. The decision cannot be obiter for what the court in effect does is to declare the law but on the basis of another doctrine restricts its scope. Stability in the law does not mean that injustice shall be perpetuated."

[54] In the case of Sarwan Kumar v. Madan Lal Aggrawal [2003] AIR 1475 (SC), the Supreme Court of India stated at p 1481 as follows:

"13.... Under the doctrine of 'prospective overruling' the law declared by the Court applies to the cases arising in future only and its applicability to cases which have attained finality is saved because the repeal would otherwise work hardship to those who had entrusted to its existence. Invocation of the doctrine of 'prospective overruling' is left to the discretion of the Court to mould with the justice of the cause or the matter before the Court."

[55] In Ling Peek Hoe & Anor v. Ding Siew Ching & Another Appeal [2017] 4 MLRA 372, Richard Malanjum CJ (Sabah and Sarawak) (as His Lordship then was) in delivering the judgment of the Federal Court, after referring to the decisions of the Indian Supreme Court in Sarwan Kumar and Golak Nath, stated thus:

"[27] We are of the view that the rationale on the applicability of the doctrine of prospective overruling as discussed by the Indian Supreme court in the above cases is logical and sound. We have no good reason not to adopt it."

[56] As was pointed out by the Federal Court in Ling Peek Hoe, 'prospective overruling' has been applied by our courts. In the case of Dato' Yap Peng, the Supreme Court applied the doctrine so that its decision would leave undisturbed earlier convictions or acquittals. In Mamat Daud & Ors v. The Government Of Malaysia [1987] 1 MLRA 292, the Supreme Court by a majority declared null and void s 298A of the Penal Code as being a provision that Parliament had no power to make under the Federal Constitution but ordered that its ruling should only take effect from the date of its order, namely, 13 October 1987. The jurisdiction was again invoked in Repco Holdings Bhd v. PP [1997] 3 MLRH 304, this time by the Court of Appeal, when it declared both ss 129(2) of the Securities Industry Act 1983 and s 39(2) of the Securities Commission Malaysia Act 1993 to be unconstitutional, null and void.

[57] In Singapore, the Court of Appeal also found it had jurisdiction to apply the doctrine of prospective overruling and held that its jurisdiction unlike that of the Courts in India, would not be limited to constitutional cases. In Public Prosecutor v. Manogaran S/O Ramu [1997] 1 SLR 22, Yong Pung How CJ observed as follows:

"Like the Indian Supreme Court in Golak Nath, this is the first occasion that this court has been called upon to consider applying the doctrine of prospective overruling. It would undoubtedly be advisable to approach the matter with a measure of circumspection. Even so, we do not propose to follow the narrow path marked out in Golak Nath. There is no compelling reason why prospective overruling must be confined only to issues arising under the Constitution. In any event, while certain of the issues arising in the present case may be characterised broadly as 'constitutional issues', the primary task before us involves statutory construction."

See also the subsequent decision of the Court in PP v. Hue An Li [2014] 4 SLR 661.

[58] Of the availability of the jurisdiction in civil cases, Sundaresh Menon CJ in the decision of the Singapore Court of Appeal in L Capital Jones Ltd And Another v. Maniach Pte Ltd [2017] 1 SLR 312 stated that:

"[71] Prospective overruling has thus far only been applied in criminal cases in our courts. In that context, there will often be a more compelling need to protect a party's legitimate expectations and/or its reasonable reliance on the previously prevailing line of authority. As the court in PP v. Hue An Li observed at [110], "special considerations must come into play in the criminal context, especially where a person's physical liberty is at stake". This does not mean, however, that prospective overruling can never be justified in civil cases. Indeed, the court further observed that "the arguments in favour of prospective overruling ... cannot be restricted solely to criminal law" (PP v. Hue An Li at [123]). It nevertheless seems to us that, in contrast to criminal cases, civil cases presenting exceptional circumstances that justify invoking the doctrine of prospective overruling are likely to be few and far between."

[59] 'Prospective overruling' is clearly an exception to the general rule. We would also emphasise, and join the chorus, in cautioning that the doctrine of prospective overruling is a jurisdiction that is not to be employed lightly but with circumspection and only in exceptional circumstances. In cases involving the avoidance of a law, which has stood for some time, for being in contravention of the Federal Constitution, the doctrine of prospective overruling would be available to give effect to the raison d'etre for its existence. It would be available to the court to, in the words of Abdoolcader SCJ, '... give such retroactive effect to its decision as it thinks fit to be moulded in accordance with the justice of the cause or matter before it ...'.

[60] For the reasons given above, and to mitigate the adverse consequences and hardship that the decision of the court may have on pensioners, we are of the view that this is an appropriate case, and in the public interest, for an order that the decision of this court is only to take effect prospectively from the date of the decision of this court ie 13 January 2022, and we so order. For the avoidance of any doubt, this decision would have effect on any pending proceedings, whether pending at first instance or pending appeal, in respect of issues relating to the declarations made.

[61] We are also conscious of the implications that the declarations made may have on the other provisions introduced by the 2013 Amendment Act. In our view, provisions that are dependent on the sections declared a nullity and void are accordingly ineffective and unenforceable.

[62] Finally, we would add that we do not doubt that the 2013 Amendment Act was passed with the benefit of retirees from the public services in mind as explained in Parliament. It is however the mechanism, that has been adopted and put in place under s 3(2) to address any less favourable situation should it arise, that fails to achieve its objective. Should this limitation be addressed, art 147 of the Federal Constitution would not be contravened.

[63] For the reasons given above, the appeal is accordingly allowed. The decision of the High Court is set aside. For ease of reference, we reiterate the declarations made namely:

i. a declaration that ss 3 and 7 of the Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013 are null and void being in contravention of art 147 of the Federal Constitution; and

ii. a declaration that ss 3 and 6 of the Pensions Adjustment Act 1980 as amended by ss 3 and 7 of the Pensions Adjustment (Amendment) Act 2013 and in force since 1 January 2013 are null and void being in contravention of art 147 of the Federal Constitution;

and the order of this court that the declarations made are only to take effect prospectively from the date of this decision, ie 13 January 2022.

[64] This case concerns a matter of public interest and learned counsel for the appellant, quite appropriately, did not seek an order as to costs. Accordingly, we make no order as to costs.