Federal Court, Putrajaya

Nallini Pathmanathan, Zabariah Mohd Yusof, Rhodzariah Bujang FCJJ

[Civil Appeal No: 02(F)-12-02-2020(W)]

8 December 2021

Trade Marks: Infringement of - Registered trade mark and passing off - Breach of dealership agreement - Whether court, in a trade mark infringement action, ought to consider disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with essential features in registered trade mark for purpose of deciding whether there was likelihood of confusion and/or deception - Whether, in a tort of passing off case, goodwill of a business could be destroyed completely by mere publication(s) of documents that made no specific reference to business owner

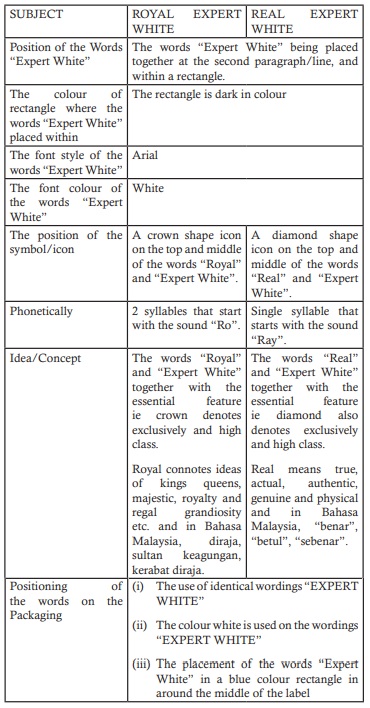

The appellant/plaintiff was a distributing company for "Royal Expert" beauty products. These products bore a "Royal Expert White" trade mark which had been registered in the Register of Trade Marks under the Trade Marks Act 1976 ("TMA") for goods in Class 3 (inter alia, creams for wrinkles and skin whitening). In that regard, the plaintiff was the owner of the registered trade mark. The 1st respondent/defendant ("D1"), the wife of the 2nd respondent/defendant ("D2"), entered into a dealership agreement ("Agreement") with the plaintiff. D2 was the sole proprietor of Rafica Resources and had distributed (together with D1) the plaintiff's products. D1 had sold skin whitening cream bearing the trade mark "Real Expert White" as well as packaging which was allegedly similar to the plaintiff's products. As a result, the plaintiff commenced an action against the defendants for the following causes of action: (i) breach of the Agreement, namely cls 7.4 and 14.4; (ii) trade mark infringement of the plaintiff's trade mark under s 38(1)(a) of the TMA when the defendants had sold "Real Expert White" products; and (iii) passing off "Real Expert White" products as the plaintiff's products.

The High Court allowed the plaintiff's claim. The defendants were held liable on all the three causes of actions and assessment of damages was ordered accordingly. On appeal, the Court of Appeal held that there was no breach of the Agreement as there was no infringement of the plaintiff's registered trade mark and the plaintiff failed to prove passing off by D1 and D2. As a result, it unanimously allowed the appeal and set aside the High Court's decision. The plaintiff was then granted leave to appeal to the Federal Court on the following questions of law: (a) whether in a trade mark infringement and passing off action, the court ought to consider the disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there was a likelihood of confusion and/or deception ("1st Question"); (b) in a tort of passing off case, could the goodwill of a business be destroyed completely by mere publication(s) of documents that made no specific reference to the business owner ("2nd Question")? The publication in this instance was a press release issued by the Ministry of Health ("MOH") that banned the product "Royal Expert Whitening Cream" for containing mercury. Given the press release, the Court of Appeal held that fundamentally the plaintiff had failed to prove that the defendants in selling the Real Expert White Cream was passing off a product of the plaintiff as the goodwill of the plaintiff's product had been destroyed.

Held (allowing the appeal with costs):

(1) The 1st Question referred to the role of disclaimers and essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there was likelihood of confusion and/or deception in the determination of infringement of a trade mark and the tort of passing off. However, the way the 1st Question was drafted was incorrect. A reading of the said question had combined/mixed the role of disclaimers in a trade mark infringement action and the tort of passing-off. The law on disclaimers vis-à-vis in the context of infringement of trade mark and in the context of the tort of passing-off was different and distinct. In trade mark infringement cases, it was the plaintiff who attached a disclaimer in the application from trade mark registration. Whereas, in a passing-off case, a disclaimer was where the defendant used a mark which was distinctive of the plaintiff, but attached a disclaimer to its usage to indicate that there was no link or nexus between the defendant's mark with that of the plaintiff. The facts in the present case showed that the defendant did not have a disclaimer stating the non-nexus between the plaintiff's goods and the defendant's. Given the aforesaid, the way the 1st Question was drafted failed to take into account this distinction of the role of disclaimers in trade mark infringement and in the tort of passing-off. Hence, the 1st Question, as it stood, was misconceived. Therefore, the 1st Question was amended to read: "Whether in a trade mark infringement action, the court ought to consider the disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there was a likelihood of confusion and/or deception?" ("Amended 1st Question"). (paras 47-50)

(2) In a trade mark infringement action, the question of whether the court ought to consider disclaimed words in juxtaposition and/or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there was a likelihood of confusion and/or deception, would be answered in the affirmative, upon the approach of the "Imperfect Recollection Test". As such, there was infringement of the trade mark. The plaintiff had, on the facts, proven all the five ingredients to constitute an infringement of its trade mark. The High Court Judge ("Judge") did not err in his findings with regards to the infringement of trade mark by the defendants. The Court of Appeal failed to compare and analyse the essential features of the trade mark of the plaintiff which was the Crown device and the Diamond shaped device on the impugned mark, but misdirected itself by focussing on the difference of the word "Royal" and "Real" which was irrelevant in determining the likelihood of confusion and/or deception in an infringement action. Case law authorities had established that where disclaimers (or referred to as "common marks") were included in the trade mark to be compared, or in one of them, the proper course was to look at the marks as a whole and not to disregard the parts which were disclaimed. The Court of Appeal disregarded the disclaimers entirely when comparing the marks of the plaintiff and the defendants. It also failed to consider the imperfect recollection of customers/customers test when making purchases in determining the likelihood of confusion/deception, but premised its decision merely on the side by side comparison test, which was erroneous. (para 112)

(3) In the present appeal, there were findings of fact by the Judge that misrepresentation had been proven by the plaintiff when he held that: (i) there existed a likelihood of confusion/deception between plaintiff's trade mark and Real Expert White mark; (ii) a phonetic comparison of the marks in question should be undertaken. A pronunciation of the plaintiff's registered trade mark and Real Expert White mark sounded confusingly similar and/or deceptively alike; and (iii) a visual comparison of the plaintiff's get-up and the get-up of Real Expert White goods showed that both get-ups had the same white and blue colours. Such similarities supported the existence of a likelihood of confusion/deception. These were findings of facts by the Judge and such findings had not been impeached by the Court of Appeal. In other words, it was not shown by the Court of Appeal that the Judge was plainly wrong in making such findings. Thus, this court was in no position to interfere with such findings. What was more telling was the fact that there was indeed clear direct evidence of ordinary sensible members of the public being confused as to whether "Royal Expert White" and "Real Expert White" were the same. The defendants (who were dealers for both Royal Expert White products and Real Expert White products) answered that they were the same. Thus, not only was there evidence of confusion by the consumer on the product of the plaintiff with that of the defendants, the defendants themselves contributed to the confusion/deception when they affirmed that both Royal Expert White cream and Real Expert White cream were the same. This was a classic passing off action, where a defendant was trying to pass his goods off as those of the plaintiff. Therefore, having regard to all the circumstances of the case, the use by the defendants in connection with the goods of the mark, name or get-up in question impliedly represented such goods to be the goods of the plaintiff, was indeed calculated to deceive. (paras 122-124)

(4) The products of the plaintiff and Real Expert White products were in direct competition with each other. In such a situation, the court would readily infer likelihood of damage to the plaintiff's goodwill through loss of sales and loss of exclusive use of the plaintiff's registered trade mark and the plaintiff's get-up. As this was a case where a defendant was trying to pass his goods off as those of the plaintiff, damage might be proven through a loss of sales or existing trade - that trade had been diverted away from the plaintiff and towards the defendant. In the present case, the Judge found that the plaintiff proved actual loss in the form of the loss of gross profits. (para 125)

(5) The Court must consider the get-up of the product as a whole and all the surrounding circumstances of the case, as such, in the determination of the likelihood of confusion and/or deception under the element of misrepresentation in the action of passing off. In the present case, there was direct evidence that the defendants were passing off the defendants' products as the plaintiff's. Hence, the Judge did not err when making findings that the tort of passing off had been made out against the defendants. (paras 126-127)

(6) As for the 2nd Question, this Court disagreed with the Court of Appeal's findings. Firstly, the press release had got nothing to do with the plaintiff's products but the products of another entity, Ortus Expert Cosmetic Sdn Bhd. There was nothing in evidence that the notification of the plaintiff's goods pursuant to the Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 ("CDCR 1984") had been cancelled by the Director of Pharmaceutical Services. With the notification, the plaintiff could sell and distribute its products. Secondly, even if it were true that the plaintiff's goods contained mercury which were contrary to the CDCR 1984 or contravening any law and that the manufacture, distribution, supply, sale and use of the plaintiffs' goods might be prohibited (which had not been proven), such a fact in itself did not mean that the use of the plaintiff's registered trade mark was contrary to law under s 14(1)(a) of the TMA. Nor did this mean that the plaintiff's registered trade mark was not entitled to protection by the Court under s 14(1)(b) of the TMA. There was a difference between the trade mark as an intangible intellectual property right and the contents of the actual goods itself. A registered trade mark conferred on its owner a form of intellectual property and statutory right under s 35(1) of the TMA. The statutory rights attached to the registered trade mark were distinct from the goods and services which bore the registered trade mark. Goodwill was attached to the brand, not the goods. (paras 133-136)

(7) If the proposition by the Court of Appeal were accepted, namely that goodwill of the products were destroyed by negative press releases, it would lead to an absurd and untenable situation where a trade mark owner would be constrained from relying on goodwill attached to its goods to prevent a third party from acts of infringement and passing off, in the event that there was negative publicity being made against its brand although the said brand could have been established in the market over a period of time. There were instances where branded goods which had established goodwill in its brand were subjected with negative publicity, yet that did not mean such branded goods lost its goodwill in the goods. The Court of Appeal had erred when it decided that the plaintiff's business no longer had any goodwill merely by the alleged banning of the product of the plaintiff by the MOH. In any event, there had been no criminal prosecution against the plaintiff nor any statutory penalties imposed. (paras 137-139)

(8) Having regard to the law and the established authorities, the Amended 1st Question was answered in the affirmative and the 2nd Question in the negative. (para 148)

Case(s) referred to:

Bata Ltd v. Sim Ah Ba & Ors [2006] 1 MLRA 762 (refd)

Bristol Conservatories Ltd v. Conservative Customs Built Ltd [1989] RPC 455 (refd)

British-American Tobacco Co Ltd v. Tobacco Importers & Manufacturers Ltd & Ors [1963] 1 MLRH 83 (refd)

Consitex SA v. TCL Marketing Sdn Bhd [2008] 2 MLRH 380 (refd)

Danone Biscuits Manufacturing (M) Sdn Bhd v. Hwa Tai Industries Bhd [2010] 1 MLRH 76 (refd)

De Cordova and Others v. Vick Chemical Company [1951] 68 RPC 10 (refd)

Elba Group Sdn Bhd v. Pendaftar Cap Dagangan Dan Paten Malaysia & Anor [1998] 1 MLRH 697 (refd)

General Cigar Co Inc v. Partagas Y Cia SA [2005] All ER (D) 505 (Jul); [2005] EWHC 1729 (Ch) (folld)

Granada Trade Mark [1979] RPC 303 (refd)

Ho Tack Sien & Ors v. Rotta Research Laboratorium Spa & Anor And Another Appeal; Registrar Of Trade Marks (Intervener) [2015] 3 MLRA 611 (folld)

Huan Schen Bhd v. SRAM, LLC (Encl 1) [2016] MLRHU 828 (refd)

J S Staedtler & Anor v. Lee & Sons Enterprise Sdn Bhd [1993] 5 MLRH 433 (refd)

Jyothy Laboratories Limited v. Perusahaan Bumi Tulin Sdn Bhd [2019] 3 MLRH 454 (refd)

John Roberts Power School v. Tessenohn [1995] FSR 947 (refd)

Low Chi Yong v. Low Chi Hong & Anor [2017] 6 MLRA 412 (folld)

M I & M Corporation & Anor v. A Mohamed Ibrahim [1964] 1 MLRA 439 (refd)

Merck KGaA v. Leno Marketing (M) Sdn Bhd: Registrar of Trade Marks (Interested Party) [2017] MLRAU 364 (refd)

Mohd Nor Afandi Mohamed Junus v. Rahman Shah Alang Ibrahim & Anor [2007] 3 MLRA 247 (refd)

Parker-Knoll Limited v. Knoll International Limited [1962] RPC 265 (refd)

Pioneer Ht-Bred CORN Co v. Hy-line Chicks Pty Ltd [1977] RPC 410 (refd)

Reckitt & Coleman Products Limited v. Borden Inc [1990] 1 AER 873 (refd)

Re Farrow's Application (1890) 7 RPC 26 (refd)

Re Lovens Kemiske Fabrik Ved A Konsted's Application For Registration Of Trade Mark "Leocillin" [1953] 1 MLRH 640 (refd)

Re Pianotist Co Ltd [1906] 23 RPC 774 (refd)

Sanbos (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v. Tiong Mak Liquor Trading (M) Sdn Bhd [2008] 1 MLRH 328 (refd)

Sarika Connoisseur Cafe Pte Ltd v. Ferrero SpA [2013] 1 SLR 531 (folld)

Saville Perfumery Ltd v. June Perfect Ltd and FW Woolworth & Co Ltd (1941) 58 RPC 147 (refd)

Seet Chuan Seng & Anor v. Tee Yih Jia Food Manufacturing Pte Ltd [1994] 1 MLRA 318 (refd)

Shizens Cosmetic Marketing (M) Sdn Bhd v. LVMH Perfumes & Cosmetics (M) Sdn Bhd [2019] 3 MLRH 623 (refd)

Sinma Medical Products (M) Sdn Bhd v. Yomeishu Seizo Co Ltd & Ors [2004] 1 MLRA 691 (refd)

Solavoid Trade Mark [1977] RPC 1 (refd)

Syarikat Kemajuan Timbermine Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Negeri Kelantan Darul Naim [2015] 2 MLRA 205 (refd)

Takako Sakao v. Ng Pek Yuen & Anor [2009] 3 MLRA 74 (refd)

Tan Hap & Anor v. Liang Ann Hock [1988] 2 MLRH 223 (refd)

Taw Manufacturing Co Ltd v. Notek Engineering Co Ltd (1951) 68 RPC 271 (refd)

The Commissioners of Inland Revenue v. Muller & Co's Margarine, Limited [1901] AC 217 (refd)

The Polo/Lauren Co, LP v. Shop-in Department Store Pte Ltd [2006] 2 SLR(R) 690 (folld)

Tint Shop (M) Sdn Bhd v. Infinity Audio Marketing Sdn Bhd [2017] MLRHU 363 (refd)

Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v. Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 350 (folld)

Valentino Globe BV v. Pacific Rim Industries Inc [2010] 2 SLR 1203 (folld)

Yong Sze Fun & Anor v. Syarikat Zamani Hj Tamin Sdn Bhd & Anor [2012] 2 MLRA 404 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984, reg 18A(1), (2), (8)

Evidence Act 1950, s 114(g)

Trade Marks Act 1976, ss 14(1)(a), (b), 18(2), 35(1), 36, 38(1)(a), 40(2), 45(1)(a)

Other(s) referred to:

Kerly's Law of Trade Marks, 8th edn, p 150

Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off in Singapore, Sweet & Maxwell, 3rd edn, vol I, pp 657-658, paras [12.031], [12.032], [12.033] & [12.040], vol II, pp 98-99, paras [19.033]-[19.035], pp 177-178, paras [19.203] & [19.205]

Counsel:

For the appellant: Eow Khean Fatt (Esther Ong Hui Chuen, Etrus Tan Chen Hee & Intan Noor Asykin with him); M/s Esther Ong Tengku Saiful & Sreeby Advocates & Solicitors

For the respondents: Rajashree Suppiah (Rex Kuan Kai Tat & Amira Nur Nadia Azhar with him); M/s Rajashree Advocates & Solicitors

JUDGMENT

Zabariah Mohd Yusof FCJ:

Introduction

[1] The appellant, Ortus Expert White Sdn Bhd was granted leave to appeal to the Federal Court on the following questions of law:

(a) Whether in a trade mark infringement and passing off action, the court ought to consider the disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there is a likelihood of confusion and/or deception?;

(b) In a tort of passing off case, can the goodwill of a business be destroyed completely by mere publication (s) of documents that make no specific reference to the business owner?

[2] In this judgment we shall refer to the parties as they were before the High Court.

[3] The plaintiff commenced an action against the defendants in the High Court premised on three causes of action, namely, infringement of trade mark of the plaintiff, breach of dealership agreement and the tort of passing off.

[4] After a full trial the learned High Court Judge decided in favour of the plaintiff on all the three causes of actions. However, upon appeal to the Court of Appeal, the decision was reversed in favour of the defendants with costs of RM40,000 to be paid to the defendants. Hence, the appeal by the plaintiff before us on the aforesaid questions of law.

Background

[5] The plaintiff is a distributing company for "Royal Expert" beauty products. These products bear a "Royal Expert White" trade mark which has been registered in the Register of Trade Marks under the Trade Marks Act 1976 (TMA) for goods in Class 3 (inter alia, creams for wrinkles and skin whitening). In that regard, the plaintiff is the owner of the registered trade mark which is set out below:

[6] The 1st defendant (D1) is the wife of the 2nd defendant (D2).

[7] D1 entered into a dealership agreement (Agreement) dated 9 September 2019 with the plaintiff. D2 is the sole proprietor of Rafica Resources (RR) and has distributed (together with D1) the plaintiff's products.

[8] D1 had sold skin whitening cream bearing the trade mark "Real Expert White" as well as packaging which is allegedly similar to the plaintiff's products. The defendants' products "Real Expert White" cream bears the mark as shown below:

[9] As a result, the plaintiff commenced an action against the defendants for the following causes of action:

(i) breach of the Agreement, namely cls 7.4 and 14.4;

(ii) trade mark infringement of the plaintiff's trade mark under s 38(1)(a) of the TMA when the defendants have sold "Real Expert White" products; and

(iii) passing-off "Real Expert White" products as the plaintiff's products.

[10] The plaintiff claims against the defendants for, inter alia:

(i) general damages for losses incurred;

(ii) an order for the defendants to give an account of all profits made by the defendants by manufacturing and/or distributing and/or selling whitening cream under the brand "Real Expert White"; and

(iii) an injunction to restrain the defendants or their agents from manufacturing and/or distributing and/or selling whitening cream under the brand "Real Expert White".

Proceedings At The High Court

[11] The case went for full trial in the High Court and at the close of the plaintiff's case, the defendants elected not to adduce any oral evidence.

[12] At the end of the trial, the High Court allowed the plaintiff's claim. The defendants were held liable on all the three causes of actions and assessment of damages was ordered accordingly.

[13] The issues addressed before the High Court were:

(i) What is the effect when the defendants elected not to adduce oral evidence in this case;

(ii) Whether the defendants have breached the Agreement by selling Real Expert White Products;

(iii) Whether the defendants could rely on a press release from the Ministry of Health pertaining to the application of reg 18A of the Control of Drugs and Cosmetics Regulations 1984 (CDCR 1984);

(iv) Whether the defendants infringed the plaintiff's registered trade mark under s 38(1)(a) TMA by selling Real Expert White Products. In determining whether there was an infringement of the trade mark, the following issues arose:

a. pursuant to ss 18(2), 35(1) and 40(2) TMA, what is the effect of a "Disclaimer/Condition" in the plaintiff's Registered Trade Mark; and

b. can the defendants rely on s 14(1)(a) and (b) TMA when there is no counterclaim by the defendants under s 45(1)(a) TMA to remove the plaintiff's registered trade mark from the Register. In this regard, is there a distinction between the use of a registered trade mark and the contents of goods bearing the registered trade mark?; and

(v) Whether the defendants committed the tort of passing off Real Expert White products as the plaintiff's goods.

The Effect Of The Defendant In Not Adducing Oral Evidence

[13] The learned trial Judge referred to Takako Sakao v. Ng Pek Yuen & Anor [2009] 3 MLRA 74, where the court presumed that the plaintiff's evidence to be true. The court found that the witnesses, SP1, SP2 and SP3 are credible witnesses and their evidence was not undermined during cross-examination. The court invoked an adverse inference under s 114(g) of the Evidence Act 1950 when the defendant failed to adduce any evidence to rebut the evidence of the plaintiff.

[14] The basis for such holding by the learned trial Judge are:

(a) If the defence wishes to make a submission of no case to answer, then the trial court is under an obligation to put to the election of the defence counsel that he would not call any evidence. The reason for such obligation is that no judge should be asked for his conclusion or opinion on the evidence until such evidence is concluded.

(b) If the party on whom the burden of proof lies, gives or calls evidence, then the judge is bound to call upon the other party, and has no power to hold that the first party has failed to prove his case. At this stage the truth or falsity of the evidence is immaterial. For the purpose of testing whether there is a case to answer, all the evidence given must be presumed to be true.

(c) Therefore, once a defendant elects not to call evidence, then all the evidence led by the plaintiff must be assumed to be true.

Whether The Defendants Have Breached The Agreement By Selling Real Expert White Products?

[15] It was held that the Agreement was between D1 and the plaintiff. D2 was never a party to the Agreement although the Agreement states that D1 traded under RR's name and that she was an employee of RR. As a result, the court found that D2 could not be held liable under the Agreement premised on the doctrine of privity of contract.

[16] Consequently, the court was satisfied that D1 has breached clause of the Agreement which provides:

"7.4 The Dealer shall at all times conduct its business in such a manner as to enhance the reputation and credibility of the Company and Products. It shall, in particular:

7.4.1. refrain from participating in any unlawful, unfair, deceitful or immoral practices and refrain from selling the Products to any other dealer or organisation, which has recourse to such practices; and

7.4.2. present the Products in a fair and appropriate manner. For such purpose, the Dealer shall not disparage the Company and the Products and shall not make statements concerning the characteristics or capabilities of the Products which may not be in accordance with those described in this documentation; nor shall the Dealer market the Products for correspondence."

D1's sales of Real Expert White products was to enhance the reputation and credibility of the plaintiff and the plaintiff's products, as clearly stated in the said Clause.

[17] It was also found that D1 has breached cl 14.4 of the Agreement when she failed to notify the plaintiff promptly regarding the "actual, threatened or suspected" infringement of the plaintiff's registered trade mark and the tort of passing off. Clause 14.4 provides:

"14 April The dealer must promptly and fully notify the Company of any actual, threatened or suspected infringement in the Territory of any intellectual property of the Company that comes to the dealer's notice, and of any claim by any third party coming to his notice that the importation of the Products into the Territory or their sale in it infringes any rights of any other person."

Whether The Defendants Can Rely On A Press Release From The Ministry Of Health Pertaining To The Application Of Regulation 18A Of The Control Of Drugs And Cosmetics Regulations 1984?

[18] D1 contended that based on the Ministry's Press Release, Ortus Expert White's registered trade mark should not have been registered by the Registrar of Trade Marks as the use of the same would be contrary to law, namely, reg 18A of the CDCR 1984 (as provided under s 14(1)(a) of the TMA) and is not entitled to protection by the court (as provided under s 14(1)(b) of the TMA).

[19] The learned High Court Judge rejected such argument by D1 and held that D1 is precluded from relying on the Ministry's Press Release as it concerned Ortus Expert Cosmetics Sdn Bhd (OEC) products and not that of the plaintiff, Ortus Expert White. Based on trite principle of separate legal entity, Ortus Expert White is a legal entity which is distinct and separate from Ortus Expert Cosmetics Sdn Bhd The court could not lifted the corporate veil of the plaintiff and OEC as the defendants failed to plead that OEC and plaintiff are part of a single group entity and neither was such evidence adduced by the defendants during trial.

[20] The plaintiff's products are included in the list of Registered/Notified Products, therefore they are "notified cosmetic" within the meaning of reg 18A(1) and (2) of the CDCR 1984. Under the CDCR 1984, reg 18A(1) provides:

"(1) No person shall manufacture, sell, supply, import, possesses any cosmetics-

(a) unless the cosmetic is a notified cosmetic;"

Regulation 18A(2) provides that:

"(2) For the purpose of subregulation (1), "notified cosmetics" means a cosmetic as specified in the notification issued by the Director of Pharmaceutical Services, in the manner as he deems fit."

Under the CDCR 1984, it is an offence for anyone to manufacture, sell, supply, import, possesses any cosmetics without prior notification to the Director of Pharmaceutical Services. In the present case there was no evidence to show that the Director of Pharmaceutical Services has cancelled the notification of the plaintiff's products pursuant to reg 18A (8) of the CDCR 1984. With this notification, the plaintiff is entitled to "sell, supply, import, possess or administer" the plaintiff's products.

As the Ministry's Press Release is in reference to another entity which is not the plaintiff, it therefore follows that the defendants cannot rely on the Ministry's Press Release to argue that the plaintiff's registered trade mark should not have been registered by the Registrar of Trade Marks, relying on ss 14(1)(a) and (b) of the TMA.

[21] D1 also failed to adduce evidence to prove that the plaintiff, Ortus Expert White has been investigated, prosecuted and/or convicted of any offence under the CDCR 1984 regarding Ortus Expert White's beauty products.

Whether The Defendants Infringed The Plaintiff's Registered Trade Mark Under Section 38(1)(a) TMA By Selling Real Expert White Products?

[22] The High Court relied on the Federal Court decision in Low Chi Yong v. Low Chi Hong & Anor [2017] 6 MLRA 412, (at paras 35-37) which held that five elements must be proven to show that there was an infringement of s 38 of the TMA. The High Court found that the present case satisfies all the five elements of trade mark infringement under s 38(1)(a) of the TMA, namely:

(i) The defendants have used Real Expert White mark which so nearly resembles the plaintiff's registered trade mark so as to cause a likelihood of confusion or deception between the consumers of the plaintiff's products and Real Expert White products;

(ii) The defendants are neither the registered proprietors nor the registered users of the plaintiff's registered trade mark;

(iii) The defendants have used Real Expert White mark in the course of trade;

(iv) The defendants have used Real Expert White products within the scope of registration of the plaintiff's registered trade mark; and

(v) The defendants have used Real Expert White mark in such a manner as to render its use likely to be taken as being used as a trade mark or as importing a reference to the plaintiff or the plaintiff's registered trade mark.

[23] The learned trial Judge was satisfied that the plaintiff has discharged the legal and the evidential burden to prove the existence of a likelihood of confusion/deception through visual comparison and similarity in the types of products and descriptions. This was explained by the learned High Court Judge at para 28 of His Lordship's judgment which can be summarised as follows:

(i) There are two "distinguishing" or "essential features" of the plaintiff's registered trade mark which strike the eye and fix themselves in the recollection of the users of the plaintiff's goods ie the "Crown Device" and the "rectangle". The trial court further held that Real Expert White mark has a Diamond-shaped device which is similarly confusing and/or deceptive as the Crown Device. The Diamond-shaped device is placed at the top and the middle of Real Expert White mark (the same position as the Crown Device in the plaintiff's registered trade mark). Real Expert White mark has a rectangle (same as the plaintiff's registered trade mark);

(ii) There is a likelihood of confusion/deception because a visual comparison between the plaintiff's registered trademark and Real Expert White mark has the two distinguishing features of a Diamond-shaped device and the rectangle;

(iii) The plaintiff's goods and Real Expert White products are both cosmetics products and there is a similarity of the description between the two, namely, whitening cream;

(iv) The consumers of the plaintiff's goods and the Real Expert White products are of the same category;

(v) There is a similarity of ideas or concepts between the two products as both marks are similarly applied on the box packaging of the goods; and

(vi) Applying the "general recollection test" as explained in the Federal Court case of M I & M Corporation & Anor v. A Mohamed Ibrahim [1964] 1 MLRA 439, that a reasonable consumer with an average memory and an imperfect recollection, is likely to be deceived and/or confused between the plaintiff's registered trade mark and Real Expert White mark.

[24] The learned High Court Judge held that the court cannot consider the disclaimer in the plaintiff's registered trade mark in deciding the existence of a likelihood of confusion or deception by the defendants' use of Real Expert White mark pursuant to ss 18(2), 35(1) and 40(2) of the TMA. Therefore, no action for infringement lies in respect of the use or imitation of the disclaimed particulars.

[25] However, the learned High Court Judge held that there is a likelihood of confusion or deception by the defendants' use of Real Expert White mark based on para 23(ii) above.

On Section 14(1)(a) And (b) Of The TMA

[26] The learned High Court Judge held that the defendants cannot rely on ss 14(1)(a) and (b) of the TMA, because they did not counterclaim to remove the plaintiff's registered trade mark from the Register of Trade Marks. There is a distinction between the use of a registered trade mark and the contents of goods bearing the registered trade mark.

[27] The contents of goods, whether it is contrary to any laws or not, have no bearing on the use and/or viability of a registered trade mark. Further, a defendant in a trade mark infringement action cannot rely upon s 14(1)(a) and (b) of the TMA unless a counterclaim to expunge a plaintiff's registered trade mark is initiated.

[28] Section 14(1)(a) and (b) of the TMA provides for certain conditions for the registration of trade mark. However, the plaintiff's trade mark has already been registered. Therefore, the plaintiff's registered trade mark is prima facie valid pursuant to s 36 of the TMA.

[29] For the defendants to avail themselves of s 14(1)(a) and (b) of the TMA, they should have applied under s 45(1)(a) of the TMA to expunge the plaintiff's registered trade mark.

Whether The Defendants Committed The Tort Of Passing Off Real Expert White Products As The Plaintiff's Goods?

[30] Case laws recognised that there are tests to be fulfilled so as to constitute the tort of passing off. Essentially, the test requires a plaintiff in a passing off action based on a mark or get-up, to prove that the plaintiff enjoys goodwill in the business regarding the mark or get-up, misrepresentation and damage caused by the misrepresentation to the plaintiff's goodwill.

The learned High Court Judge was satisfied that the plaintiff's registered trademark and get-up of the plaintiff's products attract businesses and customers premised on the evidence of SP 1 and SP 2.

[31] The learned High Court Judge found that there is misrepresentation by the defendants in which the defendants have misrepresented Real Expert White products as the plaintiff's goods and is proven by the following:

(i) the existence of likelihood of confusion/deception;

(ii) a pronunciation of the plaintiff's registered trade mark and Real Expert White mark sound confusingly similar and deceptive alike;

(iii) A visual comparison of the plaintiff's get-up and the get-up of Real Expert White products shows that both get-ups have a similar white and blue colour. Such similarities support the existence of the likelihood of confusion and deception; and

(iv) There was no denial by the defendants of the allegation by the plaintiff regarding the defendants' misrepresentation in the plaintiff's demand.

[32] The plaintiff's products and Real Expert White products are in direct competition with each other, and in such situation, the Court will readily infer likelihood of damage to the plaintiff's goodwill through loss of sales and loss of exclusive use of the plaintiff's registered trade mark and the plaintiff's get-up (Refer to Seet Chuan Seng & Anor v. Tee Yih Jia Food Manufacturing Pte Ltd [1994] 1 MLRA 318). In this case, the plaintiff proved actual loss in the form of the loss of gross profit. Therefore, the tort of passing-off has been made out.

[33] As the plaintiff has proven all the three causes of action on a balance of probability, the learned trial Judge allowed the plaintiff's claim with costs.

Proceedings At The Court Of Appeal

The Effect Of The Defendants' Election In Not Adducing Evidence After The Close Of The Plaintiff's Case

[34] The primary focus for consideration at the Court of Appeal was whether the Plaintiff had fully discharged the burden of proving the infringement of trade mark or the tort of passing-off by the Defendants.

[35] The Court of Appeal accepted the position of the law that once a defendant elects not to call for evidence, apart from being bound by such election, all the evidence led by the plaintiff must be assumed to be true (Syarikat Kemajuan Timbermine Sdn Bhd v. Kerajaan Negeri Kelantan Darul Naim [2015] 2 MLRA 205). However, the fact that the defendant led no evidence or call any witness does not absolve the plaintiff from discharging its burden to prove its claim in law. The evidence adduced by the plaintiff must be sufficient to prove the claim (Mohd Nor Afandi Mohamed Junus v. Rahman Shah Alang Ibrahim & Anor [2007] 3 MLRA 247). In this case, the Court of Appeal found that the evidence adduced by the plaintiff was insufficient to substantiate its claim for infringement of trademark and the tort of passing off.

Infringement Of Trade Mark

[36] On the infringement of trade mark, the Court of Appeal was of the view that, the comparison of essential features by the High Court was gravely flawed. The only striking similarities between the two marks, are the disclaimed words "Expert White", which are not protected under the trade mark registration.

[37] The Court of Appeal held that the ideas and concept of the registered trade mark and the alleged infringing trade mark is "Royal Expert White" and "Real Expert White" which are completely distinct and different and cannot be confused with each other.

[38] Since the legal and evidential burden of proof was of the mark used by the defendants, was identical or similar, was not established by the plaintiff during the trial on the infringement of trademark, the defendant's counsel was correct when he made a no case to answer at the close of the plaintiff's case.

[39] Even if the plaintiff's evidence is unopposed and presumed to be true on the basis that the defendants elected not to adduce evidence, the law requires that the evidence adduced by the plaintiff must be sufficient to prove that the defendants had infringed the plaintiff's registered trade mark.

[40] The Court of Appeal held that comparison must be made between the plaintiff's registered trade mark and the defendants' mark as it appeared in actual use, following the guideline on the essential feature concept as set out by Mohamed Dzaiddin J in J S Staedtler & Anor v. Lee & Sons Enterprise Sdn Bhd [1993] 5 MLRH 433.

[41] It further held that the type of the plaintiff's registered trade mark is 'combined', which means that the words, picture or logo used combined together make up the registered trade mark. They must appear in this same combination for the protection against infringement of trade mark.

[42] As the plaintiff has no right to the exclusive use of the disclaimed words "Royal" and "Expert White", and based on ss 18(2), 35(1) and 40(2) of the TMA, the court cannot consider the disclaimed words in deciding the existence of a likelihood of confusion or deception. Therefore, it was held that there is no clear evidence that the defendants have used Real Expert White mark which resembles the plaintiff's registered trade mark. It was also held that the defendant's Real Expert White mark could not cause a likelihood of confusion or deception, because:

(i) On visual comparison, the plaintiff's registered trade mark has a crown device, while the defendants' Real Expert White mark has a Diamond-shape device. Therefore, they are not similar;

(ii) The ideas and concepts of the words "Royal" and "Real" are completely distinct and different, as the word, "Royal" connotes ideas of kings, queens, majestic, royalty and regal grandiosity. On the other hand, "Real" means true, actual, authentic, genuine and physical, and in Bahasa Malaysia, benar, betul, sebenar, etc.

(iii) Mere similarity phonetically in one of two words marks is not sufficient to make a case of infringement of trade mark. "Royal" has two syllables that starts with the sound 'Ro'. On the other hand, "Real" has single syllable that starts with the sound 'Ray'.

[43] Hence, the Court of Appeal held that D1 and D2 do not infringe the plaintiff's mark and not likely to cause confusion or deception. The Court of Appeal held that the plaintiff failed to discharge its burden of proof that there was an infringement of trade mark of the plaintiff.

Tort Of Passing-Off

[44] On the issue of passing off, the court held that the plaintiff failed to prove the same, for the following reasons:

(a) The element of goodwill for the product of the plaintiff ie "Royal Expert Whitening Cream" was destroyed by the Ministry's Press Statement that it contained mercury.

(b) The learned trial Judge had wrongfully referred to the list of Registered/Notified Products, whereby the list does not include the "Royal Expert Whitening Cream", and that the list contained products of the plaintiff and of another non-party to the suit. Therefore, the plaintiff had failed to prove that the defendants in selling the Real Expert Whitening Cream was passing off a product of the plaintiff and the goodwill of the plaintiff.

(c) Since there was no infringement of the plaintiff's registered trade mark, then the alleged misrepresentation also fails.

Decision Of The Court Of Appeal

[45] As there was no infringement of the plaintiff's registered trade mark and the plaintiff failed to prove passing off by the D1 and D2, the Court of Appeal held that there was no breach of the Agreement. As a result, the Court unanimously decided that the appeal was allowed with cost and the High Court's decision was set aside.

Proceedings At The Federal Court

[46] The plaintiff premised its appeal on the following grounds that the Court of Appeal had erred in holding that there was no infringement of trade mark and no likelihood of confusion and/or deception as the Court of Appeal:

(i) failed to take into consideration of the disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark in the determination of the infringement of registered trade mark and the tort of passing off (this is a novel point of law in which a question was framed for the determination of this Court);

(ii) failed to appreciate the essential features of the registered trade mark;

(iii) failed to consider the circumstances of the trade of both of the plaintiff's products and the defendants' products;

(iv) failed to consider the evidence of confusion; and

(v) took into account the defendants' unpleaded defence, namely non-use of the trade mark.

Our Decision

The 1st Question Of Law

[47] The 1st Question of law refers to the role of disclaimers and essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there is likelihood of confusion and/or deception in the determination of infringement of trade mark and the tort of passing off.

[48] However, before we proceed to determine the 1st Question of law, we need to state our view on the way the 1st Question of law was drafted, which we view as being incorrect. A reading of the said question has combined/mixed the role of disclaimers in trade mark infringement action and the tort of passing-off.

[49] The law on disclaimers vis-a-vis in the context of infringement of trade mark and in the context of the tort of passing-off is different and distinct. In trade mark infringement cases, it is the plaintiff who attaches a disclaimer in the application from trade mark registration. Whereas, in a passing-off case, a disclaimer is where the defendant uses a mark which is distinctive of the plaintiff, but attaches a disclaimer to its usage to indicate that there is no link or nexus between the defendant's mark with that of the plaintiff. We also need to state at the outset that the facts in the present case show that the defendant did not have a disclaimer stating the non-nexus between the plaintiff's goods and the defendant's.

[50] Given the aforesaid, the way the 1st Question of law was drafted failed to take into account this distinction of the role of disclaimers in trade mark infringement and in the tort of passing-off. Hence, the 1st Question of law as it stands, is misconceived. This was also in accordance to the submission of the plaintiff. Therefore, on our own motion, we amend the 1st Question of law to read:

Whether in a trade mark infringement action, the court ought to consider the disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there is a likelihood of confusion and/or deception?

(hereinafter referred to as "the Amended Question 1")

We now proceed to answer the Amended Question 1.

The Amended Question 1

[51] There is a disclaimer in the plaintiff's registered trade mark, in that the plaintiff has no right to the exclusive use of the words "Royal" and "Expert White".

[52] The Court of Appeal is of the view that the court cannot consider the disclaimed words in deciding on the existence of a likelihood of confusion and deception and it is to be borne in mind that the trade mark of the plaintiff is a "combined" trade mark. This means the words used, the picture or logo used combined together make up the registered trade mark of the plaintiff. When the type of trade mark is combined, the registration will not protect the words only or the picture only in isolation. Hence, they must appear in this same combination mark for protection against infringement of trade mark. Moreover the disclaimed words are not protected under the TMA pursuant to ss 18(2), 35(1) and 40(2) of the same.

[53] However, counsel for the plaintiff submits that the Court of Appeal had erred when it failed to take into consideration the disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark in a trade mark infringement.

[54] The plaintiff's stand is that the disclaimed word(s) ought to be taken into consideration together with all the essential features of a trade mark or get-up when determining whether there is a likelihood of confusion and deception in a trade mark infringement instead of disregarding the disclaimed word(s) in totality. Otherwise, infringers can easily escape liability by relying on the presence of the disclaimed words in their products, as is illustrated by the present appeal where the defendants' products consist of so many similarities in several aspects.

Whether There Is Infringement Of Trade Mark?

[55] In determining whether there was infringement of trade mark of the plaintiff, s 38 of the TMA and the case of Low Chi Yong provides and established the ingredients that needs to be proved for such a cause of action:

"[37] Under s 38 of the TMA 1976 the appellant needs to establish the following ingredients, inter alia:

(i) The respondent used a mark identical with or so nearly resembling the trade mark as is likely to deceive and/or cause confusion ...:

(ii) The respondent is not the registered proprietor or the registered user of the trade mark;

(iii) The respondent was using the offending trade mark in the course of trade;

(iv) The respondent was using the offending trade mark in relation to goods or services within the scope of the registration; and

(v) The respondent used the offending mark in such a manner as to render the use likely to be taken either as being used as a trade mark or as importing reference to the registered proprietor or the registered user or to their goods or services."

[56] The first ingredient as laid down in Low Chi Yong is known as "the test of Likelihood of Confusion or Deception". In this regard, the Supreme Court in the case of Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v. Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 350 sets out what constitutes an infringement of a registered trade mark when it held as follows:

"Under s 38 of the Trade Marks Act 1976, a registered trade mark is infringed by a person who uses a mark which:

(a) is identical with it; or

(b) so nearly resembling it as is likely to deceive; or

(c) so nearly resembling it as is likely to cause confusion."

[Emphasis Added]

[57] Section 38 TMA explicitly requires the court to consider whether such resemblance of the trade mark is likely to deceive or cause confusion. Mere resemblance is insufficient. The resemblance must be such as to cause a likelihood of deception or confusion amongst customers.

[58] The word, "likely" denotes what is required to be established is only a probability or possibility of confusion/deception (as per Azahar Mohamed J (as he then was) in the High Court case of Danone Biscuits Manufacturing (M) Sdn Bhd v. Hwa Tai Industries Bhd [2010] 1 MLRH 76).

[59] As for the word, "deceived", we are aided by the judgment of the Court of Appeal of New Zealand in the case of Pioneer Ht-Bred CORN Co v. Hy-line Chicks Pty Ltd [1977] RPC 410, to mean, "the creation of an incorrect belief or mental impression". As to the words "cause confusion" it "means perplexing or mixing up the minds of the purchasing public".

[60] In the infringement of a trade mark action, the determination of whether there is likelihood of confusion/deception of the public ultimately lies with the Court and not for the witnesses to decide. Support for this proposition can be found in the Federal Court case of Ho Tack Sien & Ors v. Rotta Research Laboratorium Spa & Anor And Another Appeal; Registrar Of Trade Marks (Intervener) [2015] 3 MLRA 611; Judgment of Lord Hodson in Parker-Knoll Limited v. Knoll International Limited [1962] RPC 265, 285).

[61] The issue as to whether the mark used by the defendant is identical with, or so nearly resembling the trade mark of the plaintiff, as is likely to deceive or cause confusion, is a question of fact having regard to the particular circumstances of the case (refer to M I & M Corporation & Anor v. A Mohamed Ibrahim [1964] 1 MLRA 439; Tan Hap & Anor v. Liang Ann Hock [1988] 2 MLRH 223). It is the duty of the court to conduct an enquiry as to whether a mark resembles another and this involves the eye as well as the ear together with some composite factors like phonetics and semantics.

[62] Whilst there is no formula to determine the degree of resemblance before one can determine that a mark so nearly resembles another as is likely to cause confusion, there are however, several guidelines devised by the courts through decided cases, which we will elaborate in the later part of this judgment.

The Legal Position Of "Disclaimed" Words In A Registered Trade Mark

[63] Section 18 of the TMA provides that a disclaimer is a condition upon the Register of Trade Mark, that the proprietor shall disclaim any right to the exclusive use of any such part or matter. Further provisions can be found in ss 35(1) and 40(2) of the TMA which provide that the proprietor of a registered trade mark does not have exclusive right to use in relation to the disclaimer.

[64] Ambrose J in the Singapore case of British-American Tobacco Co Ltd v. Tobacco Importers & Manufacturers Ltd & Ors [1963] 1 MLRH 83, accepted the following passage from Kerly's Law of Trade Marks, 8th edn, p 150, as a correct statement of the law with regards to the effect of disclaimers on proprietors of registered trade marks when His Lordship said at p 198 of the judgment:

"The effect of a disclaimer is that the proprietor of the registered trade mark cannot claim any trade mark rights in respect of the parts of the mark to which the disclaimer relates, so that, for instance, no action for infringement lies in respect of the use or imitation of the disclaimed particulars."

[65] As no exclusive trade mark rights may be claimed in relation to disclaimers, a subsequent application for a trade mark is free to use that component. A third party may use such parts in their trade mark for registration. In our present appeal, the plaintiff therefore has no exclusive right to the use of the disclaimed words "Royal" and "Expert White".

[66] Our High Courts have, over the years, the occasion to decide on the effect of disclaimer found in a mark in the following cases:

(a) Tint Shop (M) Sdn Bhd v. Infinity Audio Marketing Sdn Bhd [2017] MLRHU 363; HC ("Tint Shop");

(b) Jyothy Laboratories Limited v. Perusahaan Bumi Tulin Sdn Bhd [2019] 3 MLRH 454; HC ("Jyothy Laboratories")

(c) Shizens Cosmetic Marketing (M) Sdn Bhd v. LVMH Perfumes & Cosmetics (M) Sdn Bhd [2019] 3 MLRH 623; HC ("Shizens")

(d) Sanbos (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v. Tiong Mak Liquor Trading (M) Sdn Bhd [2008] 1 MLRH 328; HC ("Sanbos"),

but none provided a clear answer to the question of whether the courts can consider disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there is a likelihood of confusion and/or deception. The cases appear to decide as follows:

(a) The principles are only confined to the extent that the court cannot decide on trade mark infringement upon the use of disclaimed words. In other words, the court cannot decide that there is trade mark infringement solely on the basis that the defendant uses the disclaimed words itself. It does not expand further, than holding that the court cannot consider the disclaimed words at all in a holistic manner.

(b) In Sanbos, the court held that the plaintiff had no exclusive right over the numerals "99" and "999", and therefore the court disregarded the same when comparing whether the defendant's mark is confusingly similar to the plaintiff's registered trade mark. However, the court took cognisance that the plaintiff and the defendant's marks are to be looked at as a whole in order to determine the essential features of the plaintiff's registered trade mark. This will involve considering the phonetic, visual and get-up of the whole marks which would include the disclaimed words altogether, although disclaimers are not considered as essential particulars (paras 20-24). Sanbos held that the get-up which contains words and numerals in gold with a red background is not peculiar and/or distinctive of the plaintiff. Further, the numeral '9' and get-up is common to the trade. The court also finds that the plaintiff has failed to adduce any evidence on use of the "CLUB 999" mark.

(c) In Shizens, the court held that it cannot consider the disclaimed word "Lip" in deciding whether the defendant's mark infringed the plaintiff's registered trade mark, because the plaintiff had no exclusive use of the disclaimed word. However, the Court proceeded to decide the issue of infringement based on the plaintiff and defendant's marks as a whole which would mean including the disclaimed word in terms of phonetic, visual and trade channel aspects (paragraph 48 of the judgment). The court placed great emphasis on the substantial reputation of the LVMH brand or products as compared to Shizen's and thus there is no likelihood of deception/confusion between reasonable purchasers that LVMH's DIOR mark (ie Dior Addict LIP TATOO Products) will distinguish it from Shizens' LIP TATOO mark.

Given the aforesaid authorities, the current state of the law in Malaysia as to whether courts can consider disclaimed words together with essential features in trade mark infringement, is unclear. However, we take note of Shizens, which demonstrated that the court can proceed to decide the issue of infringement based on the plaintiff and defendant's marks as a whole which would include the disclaimed word in terms of phonetic, visual and trade channel aspects. We will be addressing whether courts ought to adopt this approach and whether it is legally justified to do so.

[67] As early as 1953, it has been held that in comparing marks, due allowance must be given to the fact that a mark is a whole thing and therefore should be considered in its entirety (Re Lovens Kemiske Fabrik Ved A Konsted's Application For Registration Of Trade Mark "Leocillin" [1953] 1 MLRH 640 and Tan Hap & Anor v. Liang Ann Hock [1988] 2 MLRH 223). When comparing the marks, one ought not to break down a mark into parts and compare each part with the corresponding part of the other mark to determine resembling features.

[68] Ambrose J in British-American Tobacco, agreed with the view as expressed by Lloyd-Jacob in Taw Manufacturing Co Ltd v. Notek Engineering Co Ltd (1951) 68 RPC 271 when His Lordship held that a disclaimed feature cannot be regarded as an essential particular and that a disclaimed feature is the antithesis of an essential particular. Further, Ambrose J accepted the following passage from Kerly's Law of Trade Marks, 8th edn, p 150, as a correct statement of the law, which states:

"The effect of a disclaimer is that the proprietor of the registered trade mark cannot claim any trade mark rights in respect of the parts of the mark to which the disclaimer relates, so that, for instance, no action for infringement lies in respect of the use or imitation of the disclaimed particulars."

[Emphasis Included]

[69] This particular passage by Ambrose J, has often been cited in support of the proposition that courts cannot consider disclaimed words in deciding whether there is infringement of trade mark and comparing whether there is likelihood of confusion or deception. However, such a proposition is misconceived upon a full consideration of Ambrose J's Judgment in the said case.

[70] In fact, after Ambrose J held that "no action for infringement lies in respect of the use or imitation of the disclaimed particulars", His Lordship proceeded to decide that when comparing the marks, the proper course is to look at the marks as wholes and not to disregard the parts which are common. From His Lordship's judgment, it appears that disclaimed words which was referred to as the "common parts" in the marks ought to be considered by the Court in a holistic manner in reaching a decision as to whether there is likelihood of confusion or deception. The case made specific reference to words having being disclaimed by the plaintiffs may be treated as something common to the trade. This is evident from His Lordship's view at pp 86-87 of the judgment, as reproduced below:

"The second proposition of counsel for the plaintiffs was that where common marks are included in the trade marks to be compared, or in one of them, the proper course is to look at the marks as wholes and not to disregard the parts which are common. He cited Re Farrow's Application (1890) 7 RPC 260, as authority for it. The proposition is to be found in Kerly's Law of Trade Marks 8th edn, at p 407. It was conceded by counsel for the defendants. And I accepted it as a correct statement of the law. Counsel for the plaintiffs said that the words "Gold Leaf" having been disclaimed by the plaintiffs may be treated as something common to the trade. The expression "common to the trade" has two meanings: (1) in common use in the trade; (2) open to the trade to use. Counsel meant that the words "Gold Leaf" were open to the trade to use. I found on the evidence before me that the words "Gold Leaf" were in common use in the trade; and also that red and white panels were in common use in the trade. Before applying the above proposition to the facts of this case, I had to consider the evidence adduced by the plaintiffs as to actual confusion.

...

For the proper principle to apply in comparing marks is to look at the marks as wholes and not to disregard the parts which are common."

[Emphasis Added]

[71] Similar proposition has also been held in the English case of Re Farrow's Application (1890) 7 RPC 260, where the High Court said that:

"It has been said and argued that the distinguishing feature of the applicant's trade mark is the word 'Nitedals', and that we are to regard that, and not to regard other matters contained on the trade mark, which are said to be common to the trade. It may be that those other matters are common to the trade, but in dealing with matters which are common to the trade, I think we must look at the combination of those different matters common to the trade, their collocation and arrangement; and if we find things that are common to the trade, all inserted in a similar position in a similar form, and in similar arrangements, so as to make the whole so similar as to be calculated to deceive, I think that is enough."

[Emphasis Added]

Whether Disclaimed Words Could Only Be Considered In An Action Of Expungement, Not Infringement?

[72] The plaintiff has directed our attention to the English case of Granada Trade Mark [1979] RPC 303, which was referred to, by the learned High Court Judge in Jyothy Laboratories, where His Lordship there, made a distinction between an action for infringement and expungement and held that disclaimed words could only be considered in an action of expungement not infringement. This can be discerned from His Lordship's judgment at para 54(2) which reads:

"(2) although the court cannot refer to the subject matter of a Disclaimer when an owner of a registered trade mark enforces his or her exclusive right to the use of the registered trade mark, the court may however, refer to the subject matter of the Disclaimer in deciding whether the registered trade mark should be removed from the Register on the ground of existence of a Likelihood of Deception/Confusion pursuant to the first limb of s 14(1)(a) read with ss 37(b) and 45(1)(a) TMA. This is understandable as the purpose of the first limb of s 14(1)(a) TMA is to protect the public from being deceived or confused regarding the origin or quality of goods and services by the use of a registered trade mark.

Our first limb of s 14(1)(a) TMA is similar to s 12(1) of United Kingdom's (UK) Trade Marks Act 1938 [TMA 1938 (UK)]. As such, decisions of UK's Registrar of Trade Marks (UK's Registrar) on s 12(1) TMA 1938 (UK) may be referred to in the construction of our first limb of s 14(1)(a) TMA. I rely on the following decisions of UK's Registrar-

(a) in Granada Trade Mark [1979] RPC 303, at 306, Mr Myall (from the office of UK's Registrar) ..."

[73] However, General Cigar Co Inc v. Partagas Y Cia SA [2005] All ER (D) 505 (Jul); [2005] EWHC 1729 (Ch); HC, held that such a distinction (between the effect of a disclaimer upon registration matters and infringement) is misconceived and based on a false premise. This is evident from the judgment:

"87. I accept the argument for the Registrar that General Cigar's suggested distinction between the effect of a disclaimer upon registration matters and infringement issues is based upon a false premise. A disclaimer only applies to part of a mark (because the whole of a valid mark could never be disclaimer, otherwise it would not be distinctive), and so a disclaimer only has any relevance when the marks under consideration are similar, rather than identical. This is because a disclaimer operates to affect the scope of protection by influencing the analysis of the likelihood of confusion. This concept is common to both s 10 (infringement) and s 5 (registrability), and should be applied equally in each scenario."

[Emphasis Added]

[74] General Cigar established the proposition that there should not be any difference in the approach to be taken on the effect of a disclaimer in determining confusion for the purposes of opposition to a proposed registration of a trade mark from that applicable to determine confusion in an infringement action. The Singapore Court of Appeal also adopted this approach as evident in Valentino Globe BV v. Pacific Rim Industries Inc [2010] 2 SLR 1203; CA, when it held that:

"Whilst we recognised that the case of Polo was concerned with the question of confusion relating to infringement under s 27(2) of the [1998 Act], we were unable to see why the approach to be taken for determining confusion for the purposes of opposition to a proposed registration under s 8(2) should be any different from that applicable to determine confusion under s 27(2). Moreover, and more importantly, the material words of the two provisions are identical."

[Emphasis Added]

We are also inclined to adopt such an approach in this matter.

[75] Hence, following from the abovesaid authorities, the justifications for the test of likelihood of confusion and/or deception is to be applied equally in expungement and infringement actions, namely, the court ought to consider the marks as a whole and take into account the disclaimed words in infringement action as it does in expungement actions.

[76] Thus, discerning from the aforesaid authorities, we are of the view that:

(a) In a trade mark infringement action, the court ought to consider disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in the registered trade mark for the purpose of deciding whether there is a likelihood of confusion and/or deception;

(b) The court cannot decide the issues of infringement of trade mark and likelihood of confusion and/or deception solely upon the basis of the use of disclaimed words;

(c) Disclaimed words cannot be regarded as essential feature;

(d) The court can consider disclaimed words in terms of phonetic, visual, and trade channel aspects for comparison to decide whether there is likelihood of confusion and/or deception;

(e) The court shall consider the marks as wholes and not to disregard the disclaimed words, and whether their collocation and arrangement all inserted in similar form and similar position or arrangement so as to make the whole so similar as to be calculated to confuse and/or deceive. The end purpose is whether the mark is so similar as to be calculated to cause a confusion and/or deception.

[77] To sum up, it is our judgment that the court can consider disclaimed words in juxtaposition or in combination with the essential features in determining the likelihood of confusion in a trade mark infringement action. However to determine the applicable test for likelihood of confusion and/or deception in a trade mark infringement action, it is pertinent to look at the nature and legal position of essential features.

The Legal Position Of Essential Features

[78] In the determination of the likelihood of confusion/deception in a trade mark infringement action, case law has held that the court would also consider what are the "essential" features of the registered trade mark.

[79] As to what constitutes "essential features" was explained by Sir Wilfred Green MR in the English case of Saville Perfumery Ltd v. June Perfect Ltd and FW Woolworth & Co Ltd (1941) 58 RPC 147, at p 162 line 2-9, where His Lordship held as follows:

"... traders who have to deal with a very large number of marks used in the trade in which they are interested, do not, in practice, and indeed cannot be expected to, carry in their heads the details of any particular mark, while the class of customer among the public which buys the goods does not interest itself in such details. In such cases the marks come to be remembered by some feature in it which strikes the eye and fixes itself in the recollection. Such a feature is referred to sometimes as the distinguishing feature, sometimes as the essential feature, of the mark."

[Emphasis Added]

[80] Our Court of Appeal in the case of Sinma Medical Products (M) Sdn Bhd v. Yomeishu Seizo Co Ltd & Ors [2004] 1 MLRA 691 not only affirmed and adopted the aforesaid proposition by Saville Perfumery Ltd as to what constitutes an "essential" feature but has expanded it to include the sound and significance of the word forming part of the registered trade mark used in trade, when it held as follows:

"[24] In De Cordova and Others v. Vick Chemical Co (1951) 68 RPC 103, the Privy Council held that the word 'VapoRub' was an essential feature of the trade mark, that the words 'vapour rub' so closely resembled that word as was likely to deceive, and that the mark was infringed. In his judgment, Lord Radcliffe said:

... A trade mark is undoubtedly a visual device; but it is well- established law that the ascertainment of an essential feature is not to be by ocular test alone. Since words can form part, or indeed the whole, of a mark, it is impossible to exclude consideration of the sound or significance of those words. Thus it has long been accepted that, if a word forming part of a mark has come in trade to be used to identify the goods of the owner of the mark, it is an infringement of the mark itself to use that word as the mark or part of the mark of another trader, for confusion is likely to result. ..."

[Emphasis Added]

[81] The issue then arises - how does one find or determine these "essential" or "distinguishing" features in a registered trade mark? In this regard, Sir Wilfred Green MR in Saville Perfumery Ltd at p 162 line 10-13 of the judgment, provided guidance "In deciding whether or not a feature is of this class, not only ocular examination, but the evidence of what happens in practice in the particular trade is admissible.".

[82] As to who determines these "essential" or "distinguishing" features was explained by Ambrose J in British-American Tobacco at p 86, when it held that:

"I had, however, to consider the evidence placed before the Court as to what the public regards as essential feature s of the plaintiffs' registered trade mark. The identification of an essential feature depends partly on the Court's own judgment and partly on the burden of the evidence that is placed before it: De Cordova v. Vick Chemical Co [1951] 68 RPC 103 at p 106. In that case the Privy Council said:

If a word forming part of a mark has come in trade to be used to identify the goods of the owner of the mark, it is an infringement of the mark itself to use that word as the mark or part of the mark of another trader, for confusion is likely to result."

[Emphasis Added]

[83] The above proposition was also adopted by Mohamed Dzaiddin J (as he then was) in J S Staedtler & Anor v. Lee & Sons Enterprise Sdn Bhd [1993] 5 MLRH 433, where His Lordship held that:

"Identification of these features depended partly on the court's own judgment and partly on the burden of the evidence that was placed before the Court (De Cordova v. Vick Chemical Coy [1951] 68 RPC 103, 106). In De Cordova, the Privy Council held that the word "Vepo Rub" was an essential feature of the trade mark, that the words "vapour rub" so closely resembled that word as was likely to deceive, and that the mark was infringed.

...

A trademark is a visual device and it is a well-established law that one way of ascertaining its essential features is by ocular test (De Cordova (supra), p 106)."

[Emphasis Added]

[84] A mark has been held to be infringed if one of more of its essential features are used by another trader. As was held by the Privy Council case of De Cordova and Others v. Vick Chemical Company [1951] 68 RPC 103 that:

"... They have not used the mark itself on the goods that they have sold, but a mark is infringed by another trader if, even without using the whole of it upon or in connection with his goods, he uses one or more of its essential features."

[Emphasis Added]

[85] This was followed and adopted by an English case of Taw Manufacturing Co Ltd at p 273 where the High Court held that:

"A trade mark is infringed if a person other than the registered proprietor or authorised user uses, in relation to goods covered by the registration, one or more of the trade mark's essential particulars. The identification of an essential feature depends partly upon the court's own judgment and partly upon the burden of the evidence that is placed before the court. As Lord Radcliffe observed in De Cordova v. Vick Chemical Coy (1951) 68 RPC 13 at 106: 'In most persons the eye is not an accurate recorder of visual detail and marks are remembered rather by general impressions or by some significant detail than by any photographic recollection of the whole'."

[Emphasis Added]

[86] The case of British-American Tobacco also held the same at p 84, as evident from its holding as follows:

"The first proposition of counsel for the plaintiffs was that "a trade mark is infringed if a person other than the registered proprietor or authorized user uses, in relation to goods covered by the registration, one or more of the trade mark's essential particulars". The authority cited for this proposition was a passage to that effect from the judgment of Lloyd-Jacob J. in Taw Manufacturing Co Ltd v. Notek Engineering Co Ltd (1951) 68 RPC 271 at p 273. I accepted this proposition."

[Emphasis Added]

[87] A mark cannot be said to resemble another mark within the meaning of s 38 TMA although it shares many identical features with that other mark, because the essential features of that mark are not incorporated in the other. In considering whether the two marks resemble each other, the significant factors are the essential features (Re Pianotist Co Ltd [1906] 23 RPC 774; Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v. Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 350). JS Staedtler & Anor provides a good illustration where the plaintiff's trade mark consisted of the words "Staedtler Noris" together with yellow and black thick and thin stripes running along the hexagonal wooden casing of the pencil. The defendant's products which were put on the market were of similar hexagonal wooden casing pencils which were with thick black and yellow stripes and the word "NIKKI" printed on the wooden casing. Looking at the products side by side, it is clear that both marks were definitely not identical. However, the issue was whether they nearly resembled each other. In deciding on this issue, the court found that the essential features of the marks are the striking black and yellow stripes, not the words "Staedtler Noris" or "NIKKI". Base on a visual comparison, the court found that the striking black and yellow stripes of the defendant's mark, nearly resembled that of the plaintiff's essential features of the striking black and yellow stripes mark and therefore the plaintiff's infringement action succeeded. It is the striking black and yellow stripes which is the essential features of the plaintiff's pencils.

[88] Therefore, premised on the above authorities we can collate the following principles to be borne in mind, in determining essential features in a trade mark infringement action, namely:

(a) the particular mark is remembered by some feature in it which strikes the eye and fixes itself in the recollection or mind of a consumer;

(b) a word forming part of a mark has come in the usual course of trade to be used to identify the goods belonging to the owner of the mark;

(c) essential features can be ascertained through ocular test, as well as consideration of sound and the significance of the words in the mark, because "in most persons the eye is not an accurate recorder of visual detail and marks are remembered rather by general impressions or by some significant detail than by any photographic recollection of the whole";

(d) identification of essential features is achieved through the court's own judgment and evidence; and

(e) use of one or more of a trade mark's essential features will lead to infringement of the trade mark.

[89] Therefore, upon determining the nature and legal positions of disclaimed words and essential features, we shall now proceed to consider the test for likelihood of confusion and/or deception.

The Test For Likelihood Of Confusion And/Or Deception

[90] It was argued by the plaintiff in submission that the correct test to be applied is the imperfect recollection test, and not the side by side comparison test as applied by the Court of Appeal.

[91] Authorities have established that the side by side test is not the only test to be used in determining the likelihood of confusion and/or deception. As early as 1906, Parker J in Re Pianotist Co's Application [1906] 23 RPC 774 at p 777, laid down the test to be applied, in determining whether a mark is "likely to deceive or cause confusion", in which he said:

"You must take the two words. You must judge them, both by their look and by their sound. You must consider the goods to which they are to be applied ... In fact, you must consider all the surrounding circumstances; and you must further consider what is likely to happen if each of the trade marks is used in the normal way as a trade mark for the goods of the respective owners of the mark."

[92] Our Supreme Court in Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v. Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 350 and Elba Group Sdn Bhd v. Pendaftar Cap Dagangan Dan Paten Malaysia & Anor [1998] 1 MLRH 697, adopted the tests as laid down by Parker J in Re Pianotist Co Application. This is evident from what was held by the Supreme Court in Tohtonku, that:

"We are in agreement, having regard to the "tests" as mentioned by Wan Adnan J in Chong Fok Shang, citing with approval Parker J's judgment in Re Pianotist Co Ltd, the trial Judge was correct when he concluded that:

Applying the above test and considering the appearance of the two marks together with their features I find it is not likely that ordinary purchasers would be deceived into regarding the intervener's product to be the product of the applicant."

[93] However subsequent case laws developed further tests and principles which are widely accepted and applied which are as follows:

(a) The idea conveyed by both trade marks must be compared;

(b) The marks as a whole must be compared;

(c) The 1st syllable of the trade marks is important;

(d) The effect on the ear as well as the eye must be considered;

(e) The imperfect recollection of customers/potential customers must be considered;

(f) The essential features of the trade marks must also be compared.

[94] "The imperfect recollection" of customers/potential customers is the idea or impression which each mark produces or suggests to the minds of potential customers. This is premised on the norm and reality that the average customer does not have a photographic recollection of the details of the whole mark but merely a general impression of the mark and remembers the mark by this general impression" (Blanco White TA & Jacob Robin on Patents, Trade Marks, Copyright and Industrial Designs).