Federal Court, Putrajaya

Mohd Zawawi Salleh, Hasnah Mohammed Hashim, Rhodzariah Bujang FCJJ

[Civil Appeal Nos: 02(i)-47-09-2020 (W), 02(i)-48-09-2020 (W) & 02(i)-49-092020(W)]

23 August 2021

Banking: Bankers' books - Discovery - Application for - Power of court to order discovery of bankers' books under Bankers' Books (Evidence) Act 1949 - Whether s 7 of Act empowered court to provide orders for discovery independently of O 24 Rules of Court 2012 - Whether definition of "banker's book" in s 2 of Act to be construed by taking into account current practices in the ordinary business of a bank - Evidence Act 1950, s 130(3)

Civil Procedure: Discovery - Rules governing discovery - Application for discovery of bankers' books - Whether s 7 of Bankers' Book (Evidence) Act 1949 empowered court to provide orders for discovery independently of O 24 Rules of Court 2012

These appeals concerned the application and interpretation of the Bankers' Book (Evidence) Act 1949 ('BBEA'), in particular whether the BBEA empowered a court to provide orders for discovery independently of O 24 of the Rules of Court 2012 ('ROC'). In the main suit, the plaintiff claimed for breach of fiduciary duty by the 2nd and 3rd defendants for causing the plaintiff to purchase shares in oil exploration rights in Indonesia from the 1st defendant. It was further alleged by the plaintiff that the 2nd and 3rd defendants had personal interest in the 1st defendant and failed to disclose their personal interest. The dispute in this appeal centered on applications filed by the plaintiff relating to the request for entries in the bank books relating to the defendants' accounts and the documentation relating to the inflow and outflow of funds from the said accounts, which were material to the plaintiff's claim. The plaintiff contended that the provisions of the BBEA only provided a mechanism in which a document already obtained pursuant to a discovery application under O 24 r 7A of ROC may be proved at trial. On the other hand, the defendants argued that the applications filed by the plaintiff were misconceived and an abuse of process, as the court did not have the jurisdiction to grant the orders prayed for by the plaintiff. Accordingly, the leave questions to be determined in this appeal were, whether s 7 of the BBEA empowered a court to provide orders for discovery independently of O 24 ROC; and whether the definition of "banker's book" in s 2 of the BBEA was to be construed by taking into account current practices in the ordinary business of a bank.

Held (allowing Civil Appeal No 02(i)-48-09-2020(W) and Civil Appeal No 02(i)-49-09-2020(W); and dismissing Civil Appeal No 02(i)-47-09-2020 (W) with costs)

Per Rodzariah Bujang, FCJ (majority):

(1) Given the co-existence of the two legislations (BBEA and ROC) on an almost identical subject matter, the principle of generalia specialibus non derogant applied and since the BBEA was enacted to specifically deal with banking documents, that should be the law which should govern them, not the general provisions in the ROC. In addition, although the BBEA came into existence decades earlier than the ROC, that did not automatically mean that s 7 of the BBEA was subject to the procedural requirements of discovery under O 24 ROC. Upon a reading of O 24 ROC, it was obvious that inspection of documents was a natural consequence of an order for discovery and s 7 of the BBEA sidestepped that initial step by allowing inspection straight away. In the result, the first leave question was answered in the positive. (paras 26 & 32)

(2) The definition of 'banker's book' under the BBEA must be given a purposive interpretation employing an updating approach, while ensuring that such interpretation was confined within the meaning of 'other books' with "ledger, day book, cash book and account book". Hence, 'other books' should be considered ejusdem generis. Therefore, the second question posed should be answered in the affirmative only in so far as "the current practices in the ordinary business of the bank" related to the technological advances. (Sim Siok Eng & Anor v. Poh Hua Transport & Contractor Sdn Bhd (refd)). (paras 44-45)

Per Hasnah Mohammed Hashim, FCJ (minority):

(3) The documents sought to be discovered must be specified or sufficiently described in order that it could be complied and produced by the defendants. The defendants must know the basis of the potential claim that was likely to be made against them based on the documents requested. The plaintiff must satisfy the court that the documents sought were relevant to an issue arising or likely to arise in the intended proceedings. More importantly, the plaintiff must identify the person having possession, custody or power over the documents sought. In this instance, the plaintiff sought discovery of documents and information against non-parties through the provisions of BBEA and the inherent powers of the court. The documents listed as part of the plaintiff's application were derived from sources that did not fall within the definition of "banker's book" as defined under s 2 of the BBEA and none of the said documents had been verified and proven as required under the BBEA. (paras 109, 110 & 111)

(4) The legislative intent of the BBEA was to make the proof of banking transactions easier and to facilitate the production of banker's book evidence. Section 7 of the BBEA and s 130(3) of the Evidence Act 1950 ('EA'), as well as a banker's statutory duty to secrecy under the Financial Services Act 2013 should be considered as being in pari materia. BBEA was a legislation enacted specifically for banks as a bank representative who may have to produce voluminous physical bank documents in court may be of an inconvenience that may affect the bank's daily operations. Therefore, for convenience, attested copies need only be produced and a bank was not compellable to attend as witness to prove the matters recorded in its books without special cause. Section 7 of the BBEA could not be utilised as a backdoor attempt at obtaining evidence from a bank outside of the disclosure rules provided under O 24 ROC. (para 118)

(5) Where the permanent record was a computer document, the admitting of that document under the BBEA must not only fulfil the requirements of ss 3, 4 and 5 of the BBEA, it must also comply with the certification requirements under s 90A of the EA. This approach would negate any inconsistency between the BBEA and the EA. Any other reading would not only lead to a conflict between the two statutes, but also be repugnant to the BBEA and render it redundant. (para 127)

(6) Judges must be cautious when applying the definition to the current banking practice. The subjective views of a judge on what ought to be included as a "banker's book" could not prevail over what had been prescribed by the written laws. The court must interpret legislation purposively and hence could not import words that were not there. The purposive interpretation was permitted only to the extent as the law allowed. Hence, disputed documents outside the scope of the BBEA for not being copies of entries in banker's book should be excluded. The High Court Judge in this case failed to specifically identify which of the disputed documents were or were not "banker's book". In the result, both leave questions were answered in the negative. (paras 129, 130, 134 & 136)

Case(s) referred to:

Arnold and Hayes [1887] 3 Ch D 731 (refd)

Barker v. Wilson [1980] 1 WLR 884 (refd)

Chan Swee Leng v. Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation Ltd [1996] 4 MLRH 666 (refd)

Goh Hooi Yin v. Lim Teong Ghee & Ors [1975] 1 MLRH 472 (refd)

Mulley v. Manifold [1959] 13 CLR 341 (refd)

Norwich Pharmacal Co v. Customs & Excise Commissioners [1974] AC 133 (refd)

Ong Boon Hua & Anor v. Menteri Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri Malaysia & Ors [2008] 1 MLRA 759 (refd)

Pean Kar Fu v. Malayan Banking Bhd; Toh Boon Pin (Intervener) [2003] 4 MLRH 230 (refd)

R v. Walsall Metropolitan Borough Council [2014] EWHC 1918 (refd)

Shah & Co v. State of Maharashtra [1967] AIR SC 1877 (refd)

Shun Kai Finance Co Ltd v. Japan Leasing HK Ltd (No 2) [2001] 1 HKC 636 (refd)

Sim Siok Eng & Anor v. Poh Hua Transport & Contractor Sdn Bhd [1980] 1 MLRA 618 (refd)

South Staffordshire Tramways Company v. Ebbsmith [1895] 2 QB 669 (refd)

Teoh Peng Phe v. Wan & Co [2000] 4 MLRH 220 (refd)

Waterhouse v. Barker [1924] 2 KB 759 (refd)

Wee Soon Kim Anthony v. UBS AG [2003] 2 SLR(R) 91 (refd)

Williams v. Summerfield [1972] 3 WLR 131 (refd)

Yam Kong Seng & Anor v. Yee Weng Kai [2014] 4 MLRA 316 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Bankers' Books (Evidence) Act 1949, ss 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7(2)

Bankers' Books Evidence Act [UK], s 7

Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989

Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009

Companies Act 1965, s 4(1)

Companies Act 2016, s 2

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, s 25(2)

Evidence Act 1950, ss 3, 34, 90A(1), (2), 90B, 90C 130(3)

Financial Services Act 2013, ss 2, 6, 133(1), (4), 134(1), (4), 145

Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967, s 17A

Limitation Act 1953, s 27(1)

Rules of Court 2012, O 24, rr 3(1), 7(1), 7A(1), (2), 8, 9, 10(1), 11(1), O 92 r 4

Rules of the High Court 1980

Other(s) referred to:

Halsbury's Laws of England, 4th edn, Vol 13 at p 2 para 1 & p 4 para 2

Halsbury's Laws of England, 5th edn, vol 48, para 230

Paul Matthew and Hodge M Malek QC, Disclosure, 5th edn, para 10.37

Counsel:

For the appellant: S Sivaneindiren (Peter Skelchy & Joycelyn Teoh with him); M/s Cheah Teh and Su

For the respondents: Malik Imtiaz Sarwar (Khoo Suk Chyi, Lim Yvonne & Ng Keng Yeng with him); M/s BH Lawrence & Co

JUDGMENT

Rhodzariah Bujang FCJ (Majority):

[1] The appellant, who was the plaintiff in the suit filed in the High Court, has been granted by this court leave to appeal against the decision of the Court of Appeal which overturned that of the High Court in respect of two interlocutory applications heard by the learned High Court Judge. The respondents were the appellant's former directors and were sued by the appellant together with a company, PT Anglo Slavic Utama ("PT Anglo"), who was named the 1st defendant in the suit and who was allegedly under the respondents' control. The 1st defendant was also a substantial shareholder of the appellant. The claim against them was premised on an alleged conspiracy by all three of them to defraud the appellant and as against the respondents it was also grounded on breaches of their fiduciary duties owed to it which had caused a substantial monetary loss of USD27 million to the appellant. That amount, which the appellant now seeks to recover from them, was the monies the appellant had paid PT Anglo and PT Anglo Slavic Indonesia ("PT ASI") for the acquisition of 76% of the total issued share capital in the latter by the appellant, which would indirectly give the appellant the right over a licence to develop an oil field in Aceh Tamiang Regency, in the Province of Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam, Indonesia as explained in paras 9 and 10 of the appellant's statement of claim. That acquisition was done vide a sale and purchase agreement dated 28 December 2012 and which was subsequently amended vide an agreement dated 29 January 2014.

The Applications

[2] I have made a conscious decision to summarily state the rudimentary background facts above, for given the nature of the leave questions granted to the appellant to appeal to this court, these are sufficient to understand the legal dispute now troubling the parties. As stated above, the dispute centers on the two applications filed by the appellant which are inter-related. The first, encl 307, on pre-trial discovery of documents, was made pursuant to s 6 and/or s 7 of Bankers' Books (Evidence) Act 1949 ("the Act") and/ or O 92 r 4 of the Rules of Court 2012 ("ROC 2012"). The order sought under this application was for the appellant to inspect and take copies of all documents in the possession of Maybank Berhad and CIMB Bank in respect of the respondents', Nutox Limited's, Abamon Technology Sdn Bhd's and JF Apex Securities Berhad's accounts held in the said Banks. The order which was granted by the learned High Court Judge on 7 January 2019 was however stayed by the Court of Appeal but that was before the said Banks had released some of the documents sought under the said order. It has to be mentioned that following clarification sought by the respondents, the learned High Court Judge limited the said order to the period between 28 December 2012 and 22 September 2014.

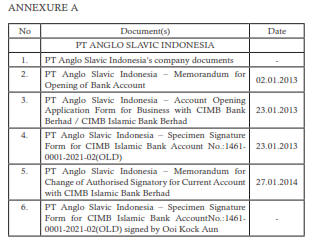

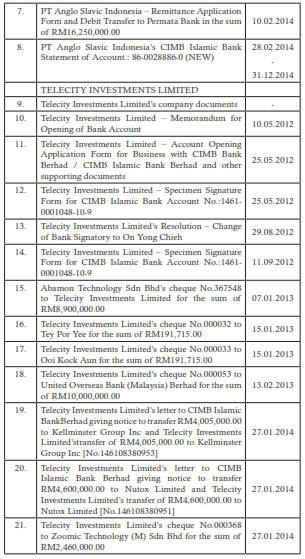

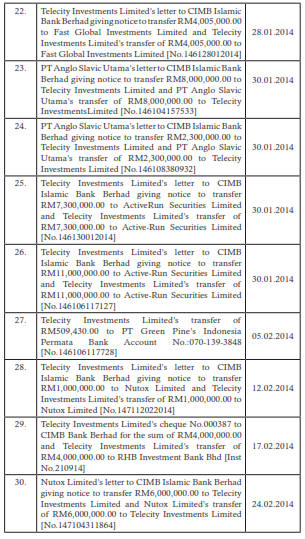

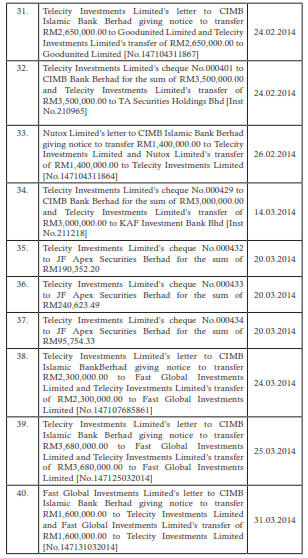

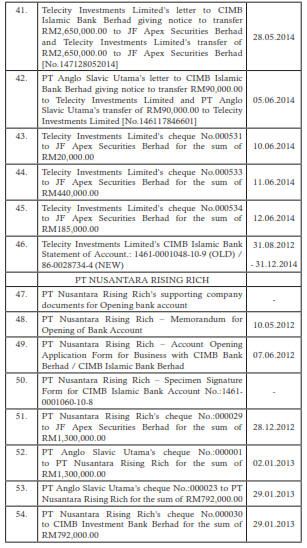

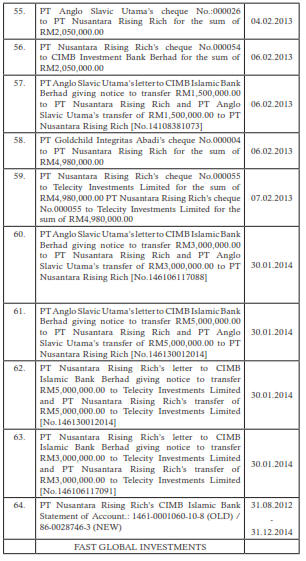

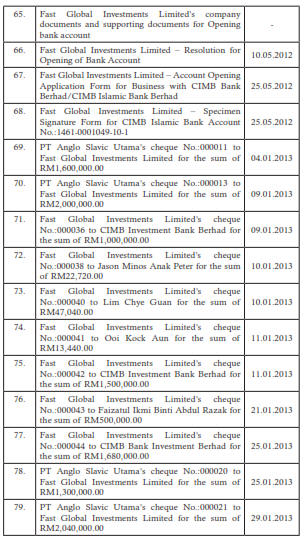

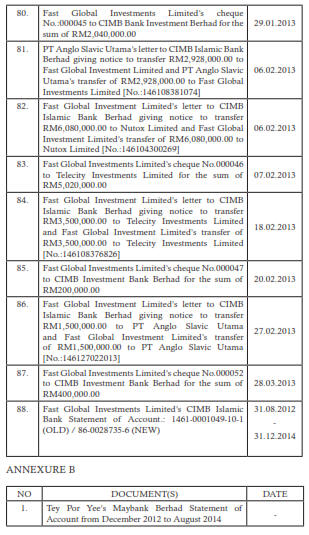

[3] The second application, encl 395, pertains to the admission of abovementioned discovered banking documents as well as the one disclosed in an application filed earlier than the said two. That first application ("encl 48"), also made under the same legal provisions as encl 307 by the appellant, and it was to inspect and take copies of all entries in the accounts of PT Anglo, PT ASI and the three related companies of the respondents, Fast Global Investments Limited, PT Nusantara Rising Rich and Telecity Investment Limited ("the three related companies") in CIMB Bank Berhad ("CIMB Bank") and CIMB Islamic Bank Berhad ("CIMB Islamic"). The appellant was moved to make this application because shortly after the appellant filed the suit in this appeal, the 1st respondent through his corporate vehicle, Kingdom Seekers Ventures Sdn Bhd, filed a derivative action against the appellant as the 7th defendant, its Managing Director, Dato' Sri Chong Ket Pen, as the 1st defendant and six other defendants for, inter alia, breach of fiduciary duties in respect of the appellant's acquisition of shares in PT ASI from PT Anglo.

[4] I paused here to note that this derivative action was struck off by the High Court on 21 April 2015 which decision was affirmed by the Court of Appeal and the matter ended there because the application for leave to appeal to the Federal Court against the said decision was dismissed. The day after that action was filed, that is, on 28 October 2014, the 1st respondent called a press conference in which he alleged that the monies the appellant paid for the acquisition of the shares were "flowed through two layers of the companies" and he identified the three related companies being some of the recipients of the monies.

[5] The respondents did not object to the application after being served with it but Fast Global Investment Limited and Telecity Investments Limited did. Nevertheless, the respondents filed and managed to obtain in the High Court a stay of the said application pending an arbitration proceeding between the appellant and PT Anglo but that stay was lifted by the Court of Appeal following an appeal filed by the appellant. Thus, an order in terms of encl 48 was granted on 25 June 2018.

[6] It was following the disclosure of the banking documents under encl 48's order, that the appellant filed that similar second one under the Act, which is, encl 307. This it did because, as submitted by the appellant's counsel before us, the documents obtained show that the respondents had personally and directly profited from the monies paid by the appellant in the acquisition of the shares and also via a circuitous route of third party entities whose names I have mentioned in para 2 above.

[7] The documents disclosed pursuant to the orders granted in encl 48 and encl 307 were enclosed in two bundles and were supposed to be adduced through the appellant's Director of Corporate Finance (PW1) but who had since passed away. However, given the objections raised by the respondents on the admissibility of the said documents, the appellant filed a formal application, that is, this encl 395 pursuant to ss 2 - 5 and/or 6 of the Act and O 92 r 4 of the ROC 2012. This move the respondents endorsed as stated by the learned High Court Judge in para 72 of his judgment as it was parties' common position that the issues as encapsulated in the two leave questions have a material impact on the admission of the said documents, thus requiring determination by His Lordship and the Court of Appeal. The disclosed documents pursuant to the aforesaid encl 48 and encl 307 were attached and marked as Annexures A & B, respectively to the said application but which I see no necessity in reproducing in this judgment of mine.

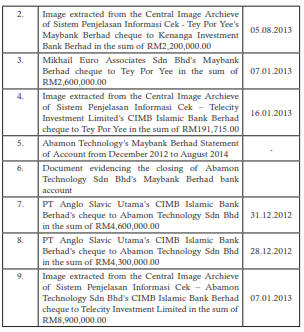

Decision Of The High Court

[8] The learned High Court Judge allowed encl 307 but dismissed encl 395 and wrote a comprehensive single judgment for both applications in which His Lordship analysed the scheme of the Act, from the time of its historical inception and the applicability of the relevant provisions of the Act and the ROC 2012. I would now reproduce the summary of the said decision which learned counsel for the appellant had ably and succinctly done in paras 43-45 of their written submission but of course with some minor editorial amendments and modifications to suit my own specific reference to the legislation in this judgment. The said summary reads:

"43. The learned High Court Judge held that the provisions of the Act entitled the appellant to seek inspection of the banker's books and to make copies of entries in such book in order to prove its assertion regarding the flow of funds back to the respondents. The learned High Court Judge held that while it is indisputably true that the intent of the legislation was to provide relief to bankers from the inconvenience of having their ledgers and other books from being removed for use in legal proceedings, the Act also, as a necessary consequence provides for a right of inspection over a banker's books as well as a right to obtain copies of entries in those books. The court held that the appellant had satisfied the test governing the principles of discovery showing the relevancy of the documents sought to the pleaded claim of the appellant. Therefore, the application did not amount to a fishing exercise.

44. The learned High Court Judge held that in applying the principles governing the provision of the Act, the court would first have to make a determination on whether the documents sought to be admitted comes within the definition of "banker's books" within the ambit of the Act. His Lordship correctly opined that that was a mixed question of fact and law. If a document satisfies the said definition, then the document may be admitted under the provisions of the Act. If a document disclosed pursuant to the order made under the Act did not come within the definition of "banker's books" within its ambit, the party in receipt of such document would be entitled to adduce that document at trial, subject to fulfilment of the requirement for proof and relevancy.

45. Finally, the learned High Court Judge held that the expression banker's books under the Act is wide enough to encompass any matter coming within the definition of "document" within the meaning of Evidence Act 1950.

According to the learned High Court Judge, in order to satisfy the said definition, a document must comprise any transaction record that is generated by the bank or must be a document which the bank maintains."

[9] Both parties appealed to the Court of Appeal against the said decision. The appellant was aggrieved by the dismissal of encl 395 and the respondents were too, not just by His Lordship's decision to allow encl 307 but also part of his decision in respect of encl 395 which allows documents that do not fall within the said definition in the Act to be admitted as evidence although subject to the usual requirements regarding proof and relevance.

Decision Of The Court of Appeal

[10] The unanimous decision of the Court of Appeal was to allow both the respondents' appeals and to dismiss that of the appellant. I am equally moved to reproduce the summary of the Court of Appeal's judgment which learned counsel for the respondents had incorporated in paras 13.1 - 4 of their written submission for just like their legal opponents, they too have ably captured the essence of the said judgment. Likewise the same is reproduced below with same editorial amendment as I had done earlier:

"13.1 A copy of any entry in a banker's book is to be received as prima facie evidence of such entry and of the matters, but the transactions and accounts therein recorded must be subject to fulfilment of ss 4 and 5 of the Act.

13.2 Enclosures 307 and 395 were in substance applications for specific discovery of documents. Such applications must conform to the rules for discovery under the Rules of Court 2012. The Act is only intended to facilitate the proving of copies of entries in bankers' books, the underlying aim of the Act being to avoid the need for bankers to give formal evidence of banker's books entries. The Act is not a means for discovery; where discovery is needed, this must be sought under the Rules of Court 2012. In this way, discovery is therefore the essential pre-requisite to the making of an order under the Act as the Act would only be called into play where a party had evidence in hand that it required formal proof from a banker to adduce.

13.3 As the Act is intended to facilitate the proving of copies of entries in banker's books thereby avoiding the requirements of the Evidence Act 1950, evidence under it can only be led where the requirements of that law are complied with in that it must be confirmed by either oral of affidavit evidence that the entry was made in the usual and ordinary course of business and the book is in the custody or control of the bank.

13.4 Given the clear legislative purpose of the Act, s 7 has to be understood in the context of its underlying legislative intention and other relevant legislation. Section 130(3) of the Evidence Act 1950 provides that no bank shall be compelled to produce its books in any legal proceeding to which it is not a party, except as provided by the law of evidence relating to banker's books. Furthermore, a banker was subject to a statutory duty of secrecy under the Financial Services Act."

[11] For clarity, the Court of Appeal's conclusion at paras 100 and 101 of its judgment are reproduced below and it is to be noted that BBEA Order 1 and BBEA Order 2 in the said excerpt refers to the orders made in encl 48 and encl 307, respectively:

"[100] Having regard to the matters stated above, our conclusion are as follows:

Enclosure 307

We agreed with the defendants that the BBEA was created to merely facilitate the proving of banking transactions through the admission of bankers' evidence. It was not intended to serve as an alternative means of discovery against bankers. The ordinary principles of discovery would not be applicable in an application under s 7 of BBEA. This is underscored by the fact that there is a specific legal framework for discovery in Malaysia, specifically O 24 of the ROC. Respectfully, the foregoing conclusions of the learned Judge were therefore erroneous. The plaintiff ought to have first establish its right to discovery under the ROC. We also agreed with the defendants that the learned Judge failed to specifically identify which of the Disputed Documents were or were not "banker's books" (Disputed Documents referred to documents purportedly obtained under BBEA Order 1 and documents purportedly obtained under BBEA Order 2. Documents such as company documents, memorandum or resolution for opening of bank account, memorandum or resolution for change of authorised signatory) are not "banker's books" as they do not permanently record transactions in the ordinary business of a bank.

Miscellaneous internal documents used by the bank (such as specimen signature form, remittance application form, account opening application form, correspondence and documents evidencing the closing of account) are not "banker's books" as they do not permanently record. transactions in the ordinary business of a bank;

Cheques and paying-in slips (such as cheque deposit receipts, transaction slips are not "banker's books" as they do not permanently record transactions in the ordinary business of a bank. They are either instructions (eg cheques) or documents evidencing the said instructions (paying-in slips) prepared merely for the purposes of customers' convenience.

Bank statements are not "banker's books" as they are created not for the purpose of permanently recording transactions in the ordinary business of a bank, but for customer's reference only.

Enclosure 395

In respect of BBEA Order 1:

The plaintiff would not be permitted to adduce under the EA documents that were improperly disclosed. Those disputed documents should be excluded for being outside the scope of the BBEA for not being copies of entries in banker's books within the meaning of s 2. The plaintiff was required to prove and verify any of the Disputed Documents that fell within the permissible scope of the BBEA Orders under ss 4 and 5 of BBEA. Failing that, the plaintiff was not permitted to rely on the Disputed Documents on the strength of the EA.

In respect of BBEA Order 2:

The plaintiff was required to prove and verify any of the Disputed Documents that fell within the permissible scope of the BBEA Orders under ss 4 and 5 of BBEA. Failing that, the plaintiff was not permitted to rely on the Disputed Documents on the strength of the EA.

[101] The learned Judge ought to have dismissed encl 307 and BBEA Order 2 ought not have been made. Enclosure 395 ought to have been treated only as applying to copies of documents produced under BBEA Order 1, and, that the end all the documents produced under BBEA Order 1 ought to have been determined as inadmissible under BBEA Orders on ground that those documents were not admissible under EA."

The Leave Questions

[12] Premised on the above judgments, it is clear that the legal grouse harboured by the parties before us is the interplay between the relevant provisions in the two laws, to wit, the Act and the ROC 2012 regarding the production and discovery of banking documents and crucially in this regard is whether the former is subject to the latter. Thus, the appellant was granted leave to appeal on these two questions of law:

Question 1

Whether s 7 of the Bankers' Books (Evidence) Act 1949 empowers a court to provide orders for discovery independently of O 24 of the Rules of Court 2012.

Question 2

Whether the definition of "banker's books" in s 2 of the Bankers' Books (Evidence) Act 1949 is to be construed by taking into account current practices in the ordinary business of a bank.

My Considerations

[13] I will begin by first reproducing the relevant provisions of the Act, starting with the definition of "banker's books", followed by those relating to proof of the same and the power of the court in relation to it.

"Section 2: "banker's books" includes any ledgers, day book, cash book, account book and any other book used in the ordinary business of a bank.

Section 3: Mode of proof of entries in bankers' books.

Subject to this Act, a copy of any entry in a banker's book shall in all legal proceedings be received as prima facie evidence of such entry and of the matters, transactions and accounts therein recorded.

Section 4: Proof that book is a banker's book.

(1) A copy of an entry in a banker's book shall not be received in evidence under this Act unless it is first proved that the book was, at the time of the making of the entry, one of the ordinary books of the bank, and that the entry was made in the usual and ordinary course of business, and that the book is in the custody or control of the bank.

(2) Such proof may be given by an officer of the bank, and may be given orally or by an affidavit sworn before any magistrate or person authorized to take affidavits.

Section 5: Verification of copy.

(1) A copy of an entry in a banker's book shall not be received in evidence under this Act unless it is further proved that the copy has been examined with the original entry and is correct.

(2) Such proof shall be given by some person who has examined the copy with the original entry, and may be given either orally or by an affidavit sworn before any magistrate or person authorized to take affidavits.

Section 6: Case in which officer of bank not compellable to produce books, etc

An officer of a bank shall not, in any legal proceedings to which the bank is not a party, be compellable to produce any banker's book the contents of which can be proved under this Act or to appear as a witness to prove the matters, transactions and accounts therein recorded, unless by order of a Judge made for special cause.

Section 7: Court or Judge may order inspection

(1) On the application of any party to a legal proceeding the Court or a Judge may order that such party be at liberty to inspect and take copies of any entries in a banker's book for any of the purposes of such proceedings.

(2) An order under this section may be made either on or without summoning the bank or any other party, and shall be served on the bank three clear days before the same is to be obeyed unless the Court of Judge otherwise directs."

[14] Order 24 of the ROC 2012 on discovery of documents contains fifteen provisions but for the purpose of my judgment, the relevant one is O 24, r 7A which in itself is a lengthy one. Therefore, suffice if I just reproduce the pertinent provision which is O 24, r 7A (1) and it reads:

"Discovery against other person (O 24, r 7A)

7A. (1) An application for an order for the discovery of documents before the commencement of proceedings shall be made by originating summons and the person against whom the order is sought shall be made defendant to the originating summons."

[15] It is apt for me to pause here to mention that O 24 r 7A was only inserted when the ROC 2012 was enacted and thus it was absent in its predecessor, the Rules of the High Court 1980. Of equal importance and pertinence, though obvious from the title of the Act itself is that the Act is a pre-Merdeka law which was legislated way back in 1949. It was modelled on United Kingdom's Bankers' Books Evidence Act 1876 which Act was re-enacted in 1879 and further amended in 1979. As explained by the learned authors, Paul Matthew and Hodge M Malek QC in their book, Disclosure 5th edn at para 10.37, that law was passed "... in order to get over the difficulty and hardship relating to the production of bankers' books. If such books contained anything which would be evidence for either of the parties, the banker or his clerk had to produce them at the trial under a subpoena duces tecum, which was an inconvenience when the books were in regular use. The leading object of this Act was to relieve bankers from that inconvenience." It also enables, said the learned authors further, for an order to be made for pre-trial disclosure of documentary evidence in the hands of the banks relating to accounts held by parties to the litigation. It is to be noted that under s 7(2) of the Act, the application for the order can be made ex parte but O 24, r 7A(2) provides that the application must be served personally on a non-party custodian of the documents.

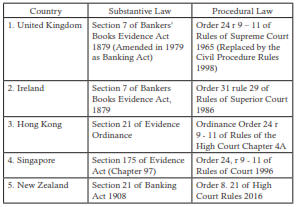

[16] At the hearing, we were also appraised by learned counsel for the appellant, and upon due verification of the same, have no reason to doubt the veracity of the facts stated by him, that not only in the United Kingdom but also in Ireland, Hong Kong and Singapore, there are similar legislations as the Act and O 24, r 7A co-existing in the aforesaid jurisdictions. Yet, submitted learned counsel further, the courts there have consistently allowed an application under the equivalent sections of the Act to inspect and make copies of banking documents despite the existence of the specific procedural law on discovery against non-parties. By way of an illustration, these legislation are tabled below:

[17] The Court of Appeal, submitted the appellant's counsel, had fallen into grave error by failing to appreciate the trite principles established by case authorities which the court must consider in granting such an order under the Act, which is, whether the documents sought are in existence, that these documents are in the possession, custody or power of the relevant banks and most importantly are relevant to the issues to be adjudicated. He cited the case of South Staffordshire Tramways Company v. Ebbsmith [1895] 2 QB 669 and Williams v. Summerfield [1972] 3 WLR 131, in support of the proposition made above.

[18] Learned counsel further submitted that the Court of Appeal was wrong to draw a distinction between discovery and inspection of document because it is elementary that in order for there to be inspection, there would first have to be production. In this connection, it is pertinent to note that O 24, r 10 of ROC 2012 is the one governing inspection of document for it provides for a notice to be served on the party who is to produce it whereas O 24 r 11 of the ROC 2012 allows for a party to make an application to court for the inspection of particular documents where the other party has not complied with r 9 or r 10(1), objects to producing the documents in question or offers inspection at an unreasonable time and venue.

[19] Learned counsel for the appellant further bolstered their argument by referring to s 130 (3) of the Evidence Act 1950 which provides that:

"(3) No bank shall be compelled to produce its books in any legal proceeding to which it is not a party, except as provided by the law of evidence relating to banker's books,"

Therefore, they submitted, the principle of generalia specialibus non derogant applies and O 24 r 7A being a subsidiary and general legislation do not abrogate but must yield to that of the Act.

[20] Learned counsel for the respondents, on the other hand, submitted that the interpretation of s 7 of the Act as providing an independent right of discovery is misconceived. This is because it directly contravenes the legislative intent underlying the Act which is to facilitate the adducing of banker's evidence and nothing more. It also fails to give due regard to the need to give a purposive interpretation of s 7 as provided in s 17A of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967 and to do so in line with statutes which are in pari materia with the Act, that is, the Evidence Act 1950 and the Financial Services Act 2013. Section 17A provides as follows:

"In the interpretation of a provision of an Act, a construction that would promote the purpose or object underlying the Act (whether that purpose or object is expressly stated in the Act or not) shall be preferred to a construction that would not promote that purpose or object."

[Emphasis Added]

[21] Citing, inter alia, Cotton LJ in Arnold and Hayes [1887] 3 Ch D 731, learned counsel stressed, as held in the cited case, that the object of the Bankers' Books Evidence Act 1879 is only to provide relief to a banker from having to attend court in order to produce at the trial his daily used books.

[22] As for their submission on the need to consider statutes in pari materia with the Act, they first referred to the decision of Shah & Co v. State of Maharashtra [1967] AIR SC 1877 which quoted Sutherland on Statutory Construction 3rd edn, Vol 2 that:

"Statutes are considered to be in pari materia - to pertain to the same subject matter - when they relate to the same person or thing, or to the same class of person or things, or have the same purpose or object and to be in pari materia , statutes need not have been enacted simultaneously or refer to one another."

[23] Therefore, said learned counsel, the Act must be construed with ss 90C and 130(3) of Evidence Act 1950 as well as s 133(1) of the Financial Services Act 2013. Section 130(3) I had reproduced earlier and I would do the same now for the said ss 90C and 133(1).

Sections 90A and 90B to prevail over other provisions of this Act, the Bankers' Books (Evidence) Act 1949, and any written law

Section 90C.

The provisions of s 90A and 90B shall prevail and have full force and effect notwithstanding anything inconsistent therewith, or contrary thereto, contained in any other provision of this Act, or in the Bankers' Books (Evidence) Act 1949 [Act 33], or in any provision of any written law relating to certification, production or extraction of documents or in any rule of law or practice relating to production, admission, or proof, of evidence in any criminal or civil proceeding.

Secrecy

Section 133.

(1) No person who has access to any document of information relating to the affairs or account of any customer of a financial institution, including:

(a) the financial institution; or

(b) any person who is or has been a director, officer or agent of the financial institution,

shall disclose to another person any document or information relating to the affairs or account of any customer of the financial institution.

(2) Subsection (1) shall not apply to any document or information relating to the affairs or account of any customer of a financial institution -

(a) that is disclosed to the Bank, any officer of the Bank or any person appointed under this Act or the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009 for the purpose of exercising any powers or functions of the Bank under this Act or the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009;

(b) that is in the form of a summary or collection of information set out in such manner as does not enable information relating to any particular customer of the financial institution to be ascertained from it; or

(c) that is at the time of disclosure is, or has already been made lawfully available to the public from any source other than the financial institution.

(3) No person who has any document or information which to his knowledge has been disclosed in contravention of subsection (1) shall disclose the same to any other person.

(4) Any person who contravenes subsections (1) or (3) commits an offence and shall, on conviction, be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years or to be a fine exceeding ten million ringgit or to both.

[24] The significance of s 90C, submitted learned counsel and which view I endorse, is that Parliament not only intended the Act to be read in tandem with the Evidence Act 1950, it also equated the Act to a written law relating to the production, admission or proof of evidence whilst s 130(3) explicity carves out the law on banker's book and recognises the Act as providing for the same.

[25] As for s 133(1) of the Financial Services Act 2013, learned counsel for the respondents submitted that given the clear prohibition against a disclosure of a customer's banking documents or information relating to his account since s 133(4) makes it an offence if this is done, s 7 of the Act should not be construed as permitting an open-ended and wide-ranging inspections. They further reinforced their argument that s 7 is not an alternative method of discovery by referring to s 25(2) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964 read with para 14 of the Schedule which provides that the High Court's power to order discovery of facts or documents by any party or person is "in such manner or may be prescribed by Rules of Court". Thus, it is their submission that by virtue of s 4 of the said Act, its provisions shall prevail over any other written law other than the Federal Constitution in the event of inconsistency or conflict between the two. Learned counsel further submitted that there is a difference between discovery and inspection from the scheme of O 24 itself where O 24, r 3(1), r 7(1) and r 7A are the provisions on discovery whereas O 24, r 9, r 10(1) and 11(1) are on inspection. Therefore, the word 'inspect' in s 7, said learned counsel cannot be equated with 'discovery' and a literal interpretation of s 7would produce unjust and absurd result. Applying the purposive approach, concluded learned counsel for the respondents, s 7 is not a tool for discovery and Question 1 should be answered in the negative.

[26] At first blush these arguments advanced by learned counsel for the respondents appear to be attractive, but I am not persuaded that is how the two legislation should be interpreted. Firstly, as rightly submitted by learned counsel for the appellant, given the co-existence of these two legislation on an almost identical subject matter, the principle of generalia specialibus non derogant applies and since the Act was enacted to specifically deal with banking documents, that should be the law which should govern them, not the general provisions in the ROC 2012. Granted that the Act came into existence decades earlier than the ROC 2012 or rather its predecessor, the Rules of High Court 1980, that does not automatically mean that s 7 is ubject to the procedural requirements of discovery under O 24. I say this because from the way O 24 itself is enacted, it is obvious that inspection of documents is a natural consequence of an order for discovery and s 7 of the Act sidesteps that initial step by allowing inspection straight away. As explained in Halsbury's Laws of England (4th edn) Vol 13 at p 2 para 1 thereof, that discovery of documents operates in three successive stages, namely:

"(1) the disclosure in writing by one party to the other of all the documents which he has or has had in his possession, custody or power relating to matters in question in the proceedings; (2) the inspection of the documents disclosed, other than those for which privilege from or other objection to production is properly claimed or raised; and (3) the production of the documents disclosed either for inspection by the opposite party or to the court."

Therefore, it would appear from an initial reading of the above passage that inspection and production of document as provided in s 7 is part and parcel of the discovery process. However, it is stated at the subsequent p 4 at para 2 that:

"Discovery should also be distinguished from the right given by various statutes to obtain inspection of particular documents, as the grounds on which discovery may be resisted are not available as defences to a claim for inspection under a statute, unless it provides that they shall be available. Thus a company incorporated under the Companies Clauses Act is bound to produce its shareholders' address book for inspection by a shareholder whatever may be his motive for requiring inspection, and a taxpayer can be compelled to produce documents relating to value added tax although they may incriminate him."

[Emphasis Added]

[27] It is also extremely important to note that in the United Kingdom, unlike Malaysia, the specific procedures relating to discovery in the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873 was enacted earlier than its Bankers' Books Evidence Act 1879. Yet the application of the former was not made subject to the latter. This goes to show that the disclosure of the banking documents specified under the Act was meant to co-exist independently of the procedural requirements under the general civil procedure rules. Given that the Act is adopted almost wholesale from that of United Kingdom, this historical perspective of interpreting the Act is relevant and it is even more so when in all the years before O 24, r 7A was enacted, there is no like provision in our civil procedural law which in any way impacted the power vested on the court by s 7 of the Act. The oneness of discovery process with disclosure or production of documents and its inspection is even acknowledged by our Court of Appeal in Ong Boon Hua & Anor v. Menteri Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri Malaysia & Ors [2008] 1 MLRA 759 when it cited Teoh Peng Phe v. Wan & Co [2000] 4 MLRH 220 which held that 'discovery' is often used to mean both disclosure and inspection.

[28] As lucidly explained in the Halsbury's Laws of England (5th edn) Vol 48 at para 230:

"The Bankers' Books Evidence Act 1879 provides that any party to a legal proceedings may apply to the court or a judge for an order that the applicant be at liberty to inspect and take copies of any entries in a banker's book for the purposes of such proceeding.

The main object of these provisions is to enable evidence to be procured and given, and to relieve bankers from the necessity of attending and producing their books. They enable a party, who formerly had the right to issue a subpoena duces tecum to compel bankers to produce their books and to attend and be examined on them, to obtain an order for leave to inspect and take copies of the books. They do not give any new power of disclosure, or alter the principles of law or the practices with regard to disclosure, or take away any previously existing ground of privilege. Nor do they enable a party to obtain disclosure, before the trial, of entries which would be privileged or protected from production, or which are, or are sworn to be, irrelevant or which are sworn to tend to incriminate, or which are not the subject of disclosure apart from the Bankers' Books Evidence Act 1879. Where, therefore, a party swears that the entries sought to be inspected are irrelevant, his affidavit is conclusive, and no order for inspection should be made before the trial."

[Emphasis Added]

[29] I fully appreciate the existence of the Financial Services Act 2013 which makes it an offence to disclose a person's banking transactions or details and that safeguard is enhanced by s 130(3) of the Evidence Act 1950 which I had reproduced earlier in para 14. However, as is clear from the words "except as provided by the law of evidence relating to banker's books" in the said subsection, it is patently obvious that the law recognises a leeway and that "law of evidence relating to banker's book" definitely refers to the Act because it was enacted earlier than the Evidence Act 1950. This consideration is further justification for me to hold that s 7 of the Act is not subject to O 24, r 7A as held by the Court of Appeal. Of course, as rightly found by the learned High Court Judge, the general rule of evidence, that is relevancy, is the cornerstone of s 7 and all other discovery applications. His Lordship was equally right when he considered that from the pleaded claim of the plaintiff, the money trail is relevant to prove or disprove its allegation of the flow of funds to the respondents.

[30] Granted, as stated in the above-mentioned excerpt from the said Halsbury's Laws of England and in Goh Hooi Yin v. Lim Teong Ghee & Ors [1975] 1 MLRH 472 and Pean Kar Fu v. Malayan Banking Bhd; Toh Boon Pin (Intervener) [2003] 4 MLRH 230 that the provisions in the Act do not create any new power of discovery, it is clear when I read the aforesaid excerpt and the said grounds of decisions, that what was meant to be emphasised is the relevancy of the banking documents sought. In Goh Hooi Yin (supra) in the last paragraph, that issue of relevancy or rather irrelevancy of the document sought is clearly stated as follows:

"Looking at the affidavit in support of the application I do not find anything to so suggest that there is some particular item in the third parties' accounts which are relevant to determine the issues before the court. The application is very much a fishing expedition."

[31] In Pean Kar Fu's case (supra), the learned High Court Judge declined to exercise his power under s 7 because His Lordship held that the application for discovery should be made in the trial court but in para 5 of the report, His Lordship acknowledged the power vested in court by s 7 when he said:

"Rightly so, there was no disagreement on the power of the court to order inspection and/or taking of copies of entries in a banker's book."

Equally pertinent to our case is the citation His Lordship made from the judgment of Roberts, CJ (Brunei) in Chan Swee Leng v. Hong Kong & Shanghai Banking Corporation Ltd [1996] 4 MLRH 666 where the utility and functions of that country's equivalent to our s 7 of the Act (which is also numbered s 7) is stated as follows:

"Although s 7 of the Act is not in terms restricted to other legal proceedings, I have no doubt that this is the object of the Act. It is to enable parties, who would otherwise not be able to do so, to inspect the books of the bank and take copies of them.

The Act is not intended to provide an alternative method of discovery for a litigant who seeks to bring legal proceedings against the bank itself.

Where the bank is itself a defendant, there is provision for an order for discovery to be made under the BHCR. Section 7 is not to be used to enable any party to those proceedings to inspect the defendant's books, in order to provide evidence such as will justify proceeding against the bank."

[Emphasis Added]

[32] Premised on the considerations above, I would answer the first leave question in the positive. In doing so, I believe that I have not run afoul of the purposive approach in the interpretation of the Act for it was clearly enacted to make adducing of evidence convenient for bankers and their customers.

Second Leave Question

[33] Section 2 of the Act defines banker's book as follows:

"banker's book" includes any ledger, day book, cash book, account book and any other book, used in the ordinary business of a bank."

This is very similar to the definition given in the United Kingdom's Act but which was amended in 1982 to move with the times and it now reads as follows:

"bankers' books" include ledgers, day books, cash books, account books and other records used in the ordinary business of the bank, whether those records are in written form or are kept on microfilm, magnetic tape or any other form of mechanical or electronic data retrieval mechanism"

In the Financial Services Act 2013, "books" carries the same meaning as that given by s 4(1) of the Companies Act 1965 and in the new Companies Act 2016.

[34] In interpreting the provisions under consideration, ss 90A to 90B of the Evidence Act 1950 are equally relevant considerations because of the clear provision of s 90C.

[35] For the purpose of this appeal, the first and last mentioned sections are the relevant ones because s 90B is merely the provision on the weight to be attached to a document or statement contained in a document which has been admitted under s 90A. Section 90C I had reproduced in full earlier and I would do so now for action s 90A.

Admissibility of documents produced by computers, and of statements contained therein

90A. (1) In any criminal or civil proceeding a document produced by a computer, or a statement contained in such document, shall be admissible as evidence of any fact stated therein if the document was produced by the computer in the course of its ordinary use, whether or not the person tendering the same is the maker of such document or statement.

(2) For the purposes of this section it may be proved that a document was produced by a computer in the course of its ordinary use by tendering to the court a certificate signed by a person who either before or after the production of the document by the computer is responsible for the management of the operation of that computer, or for the conduct of the activities for which that computer was used.

[36] In my view, what these legislative provisions simply means is that with the advent of technology, computerised versions of what is defined as banker's book are still admissible as evidence but does it mean that any other documents kept by the bank in relation to an individuals' banking account are admissible? Learned counsel for the appellant in their submission attempted to persuade us that it is so, going by the definition of 'books' in the Companies Act 2016 because under the said Act the definition is so wide that it includes any register or other record of information and any accounts or accounting records, however compiled, recorded or stored and also includes any document.

[37] This very definition is also made applicable to the Financial Services Act 2013 for as stated earlier it adopts the one under the Companies Act 1965 ie the Act prior to its amendment in 2016. Entry however is not defined under the Act but learned counsel for the appellant has referred us to the decision of Barker v. Wilson [1980] 1 WLR 884 which decision was on the definition of banker's book prior to the amendment of their Act in 1979 and which definition then is in pari materia with ours. Bridge LJ held as follows:

"The Banker's Books Evidence Act 1879 was enacted with the practice of bankers in 1879 in mind. It must be construed in 1980 in relation to the practice of bankers as we now understand it. So construing the definition of 'banker's books' and the phrase 'an entry in a banker's book', it seems to me that clearly both phrases are apt to include any form of permanent record kept by the bank of transactions relating to the bank's business, made by any of the methods which modern technology makes available, including, in particular, microfilm."

[38] This decision was cited with approval by the Singapore Court of Appeal in Wee Soon Kim Anthony v. UBS AG [2003] 5 LRC 171 where the court defined its task in the said case as interpreting the expression 'other books' in the definition of their "bankers book" which is exactly what I have to do in this case as well. The Singapore Court of Appeal held that in interpreting that expression they should take a purposive approach and recognise the changes effected in the practices of bankers. Therefore, any form of permanent record maintained by a bank in relation to the transaction of a customer should be viewed as falling within the scope of that expression and that includes correspondence between a bank and a customer which records a transaction as it formed an integral part of the account of that customer but not notes taken by a bank officer of meetings with the customer.

[39] Learned counsel for the appellant not only tried to persuade us to applythat same purposive approach but also that in accord with modern times, we should favour an 'updating' approach to statutory interpretation, which approach was adopted in R v. Walsall Metropolitan Borough Council [2014] EWHC 1918 (Admin). That approach simply means allowing the court to consider or take into account development after that law has been enacted. The justification for such an approach is explained by the court as follows:

"[45] It is not difficult to see why an updating construction of legislation is generally to be preferred. Legislation is not and could not be constantly reenacted and is generally expected to remain in place indefinitely, until it is repealed, for what may be a long period of time. An inevitable corollary of this is that the circumstances in which a law has to be applied may differ significantly from those which existed when the law was made - as a result of changes in technology or in society or in other conditions. This is something which the legislature may be taken to have had in contemplation when the law was made. If the question is asked "is it reasonable to suppose that the legislature intended a court applying the law in the future to ignore such changes and to act as if the world had remained static since the legislation was enacted?", the answer must generally be "no". A "historical" approach of that kind would usually be perverse and would defeat the purpose of the legislation."

[40] That approach this court has taken in Yam Kong Seng & Anor v. Yee Weng Kai [2014] 4 MLRA 316 when an acknowledgement of debt in a short messaging system was found to be one within the meaning of s 27(1) of the Limitation Act 1953 and it held as follows:

"It is presumed that Parliament intends the court to apply to an ongoing Act a construction that continuously updates its wordings to allow for changes since the Act was initially framed (an updating construction). While it remains law, it is to be treated as always speaking..."

[41] On the strength of these authorities, learned counsel for the appellant submitted that the Court of Appeal had fallen into error by not adopting the said approaches and in accepting respondents' submission raised for the first time in Court of Appeal that the appellant had failed to identify what were the documents sought as banker's book, when the appellant did in fact identified them in encl 48 and encl 307 as entries in the specific bank accounts of the respondents from the relevant banks as well as the specific periods of the relevant transactions.

[42] Learned counsel for the respondents whilst agreeing that 'banker's book' ought to be given an updated interpretation in accord with, and as submitted by learned counsel for the appellant as well, the definition of 'computer' and 'document' in s 3 of the Evidence Act 1950, however submitted that the definition of 'document must be construed ejusdem generis with the definition of 'bankers book' in the Act, that is, with the words "ledger, day book, cash book and account book". Therefore, the court is not at liberty, said learned counsel, to ignore the language of the Act, or its underlying purpose, when providing an updated interpretation of the definition of "banker's book" and that such an exercise is permitted only to the extent the law allows. Thus, s 90A of the Evidence Act 1950, submitted learned counsel further only allows for that updating within the scope permitted by that provision.

[43] In discharging the court's interpretative task here, learned counsel for the respondents also cautioned us against applying decisions from other jurisdictions and singled out Wee Soon Kim's case (supra), which ratio I had stated earlier. His reasons against adopting the same liberal approach here, are two-fold and couched on these words:

1. Though s 17A, of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967 obliges a Malaysian court to interpret legislation purposively, that provision does not give licence to a court to insert words that are not there. The purposive interpretation is permitted only insofar as the law allows; the courts are not at liberty to stretch any terms beyond its logical meaning and underlying purpose.

2. The courts do not legislate, they merely interpret. As observed by Abdull Hamid Embong FCJ in delivering the judgment of this Honourable Court in Dato' Seri Anwar bin Ibrahim v. Public Prosecutor [2010] 1 MLRA 131, para 35, "changes in the law is for Parliament to decide, not the judiciary. Judges interpret the law. And judges, under the guise of interpretation should not provide their own preferred amendments to statutes".

[44] Having given the submission and authorities cited by learned counsel for both parties my deepest consideration, I am persuaded that the definition of 'banker's book' under the Act must be given a purposive interpretation and that it is to be done with an updating approach as outlined earlier but in so doing I would still and must confine the meaning of 'other books' with "ledger, day book, cash book and account book". So it cannot be just any documents in the bank's possession which comes within that definition although, as I had said earlier, those very same documents produced or kept by the bank in accordance with advancement in technology such as computers and other forms of information technology should qualify. In other words, as rightly submitted by learned counsel for the respondents, 'other books' should be considered ejusdem generis. Doing so does not, in my view disentitle me from adopting the same approach taken in Wee Soon Kim's case (supra) because recorded transactions between the customer and the bank indeed qualify under record or entries kept in its "ledger, day book, cash book and account book". As rightly noted in the judgment of the Court of Appeal at para 76 thereof, entry is not defined in the Act but cross-referencing it with s 34 of the Evidence Act 1950, it should be the ones recorded in a book of account regularly kept in the course of the bank's business, which is one of the conditions of admissibility under the said section as held by the Supreme Court in Sim Siok Eng & Anor v. Poh Hua Transport & Contractor Sdn Bhd [1980] 1 MLRA 618.

[45] Based on the qualification above, I would thus answer the second question posed in the affirmative only in so far as "the current practices in the ordinary business of the bank" relates to the technological advances which I had alluded to earlier and no other. In doing so, I would affirm the ultimate decision of the learned High Court Judge as explained in para 43 of his judgment, to first determine whether the documents disclosed under the two orders come within the definition of "banker's book" before admitting them as evidence at the trial and if not, the admission of the intended documents will have to comply with the legal requirements for the said admission. This decision I make because as pointed out by learned counsel for the appellant and this fact I had mentioned earlier, the appellant did in encl 48 and encl 307, identify and specify in the said applications, the entries in the respondents' and the other named entities' bank accounts with the said banks including the specific periods of the transactions. That course of action adopted by the learned High Court Judge, in my view, is a fair and just one for both parties. Additionally, I would like to add, as held in South Staffordshire Tramsway Company v. Ebbsmith [1895] 2 QB 669 and Waterhouse v. Barker [1924] 2 KB 759, that in exercising the said power over documents which come under the aforesaid definition, the learned High Court Judge is still governed by the general rules relating to admission of documents at the trial, relevancy being the cornerstone of that. As held in the latter cited case:

"It is a strong thing to order a bank to disclose the state of its customer's account and the documents and correspondence relating to it. It should only be done when there is a good ground for thinking the money in the bank is the plaintiff's money - as, for instance, when the customer has got the money by fraud - or other wrongdoing - and paid it into his account at the bank."

[Emphasis Added]

[46] In conclusion and for the reasons stated above the decision of the learned High Court Judge is affirmed. Consequentially, I would allow appeal No 02(i)48-09-2020(W) and appeal No 02(i)-49-09-2020(W) but not appeal No 02(i)47-09-2020 (W) which is dismissed with costs to be in the cause of the trial in the High Court as agreed by the parties after the delivery of the summary of this judgment.

[47] My learned brother Justice Zawawi bin Salleh, has read this judgment in draft and has expressed his agreement with it.

Hasnah Mohammed Hashim FCJ (Minority):

Introduction

[48] The appeals concern the application and interpretation of the Bankers' Book (Evidence) Act 1949 (BBEA), in particular whether the BBEA empowers a court to provide orders for discovery independently of O 24 of the Rules of Court 2012 (ROC).

[49] The appellant appealed against the decisions of the Court of Appeal given on 6 March 2020 in respect of the following:

(i) Civil Appeal No W-02(IM)(NCC)-179-01/2019 (Appeal 179);

(ii) Civil Appeal No W-02(IM)(NCC)-715-04/2019 (Appeal 715); and

(iii) Civil Appeal No W-02(IM)(NCC)-741-04/2019 (Appeal 741).

[50] Appeal 741, Appeal 179 and Appeal 715 (collectively the COA Appeals) emanated from two separate applications filed by the Appellant in the High Court, pursuant to the BBEA, namely encl 307 and encl 395.

[51] For clarity, the parties will be referred to, like what they were referred to at the High Court as the plaintiff and the defendants respectively.

[52] Appeal 179 is the appeal filed by the defendants in respect of encl 307. Appeal 715 is the appeal filed by the defendants in respect of encl 395. Appeal 741 is the appeal filed by the plaintiff in respect of encl 395:

(i) Appeal 179 is against the whole of the High Court order dated 7 January 2019 which allowed the plaintiff's application under Encl 307 for disclosure under the provisions of the BBEA;

(ii) Appeal 715 is the 2nd and 3rd defendants' appeal against part of the High Court decision given on 15 March 2019 which dismissed the plaintiff's application (encl 395) for an order that all the documents previously disclosed under the orders granted pursuant to BBEA be admitted and/or taken as evidence and marked as exhibits; and

(iii) Appeal 741 is the plaintiff's appeal against the whole of the High Court decision given on 15 March 2019 which dismissed the plaintiff's application (encl 395) for an order that all the documents previously disclosed under the order granted pursuant to the BBEA be admitted and/or taken as evidence and marked as exhibits.

[53] The Court of Appeal allowed the 2nd and 3rd defendants' appeals in Civil Appeal 179 with an order that encl 307 be dismissed and BBEA Order 2 be set aside. The 2nd and 3rd defendants' appeal in Appeal 715 was allowed with an order that the documents produced under BBEA Order 1 are inadmissible, and that all copies of those documents be expunged from the court file. The plaintiff 's Appeal 741 is dismissed.

[54] On 25 August 2020, this court granted leave in respect of the following questions of law:

Question 1

Whether Section 7 of the BBEA empowers a court to provide orders for discovery independently of O 24 of the Rules of Court 2012; and

Question 2

Whether the definition of "banker's book" in s 2 of the BBEA is to be construed by taking into account current practices in the ordinary business of a bank.

The Factual And Procedural Background To This Appeal

[55] The facts are largely undisputed. On 22 September 2014, the plaintiff commenced an action in the High Court against the defendants. The plaintiff is a public listed company listed on the Main Board of Bursa Securities Malaysia. plaintiff's principal business is in construction, education, property development, road maintenance and other related business. The 2nd and 3rd defendants are the former directors of the plaintiff. In the main suit, the plaintiff is claiming for breach of fiduciary duty by the 2nd and 3rd defendants for causing the plaintiff to purchase shares in oil exploration rights in Indonesia from the 1st defendant. It is further alleged by the plaintiff that the 2nd and 3rd defendants had personal interest in the 1st defendant and failed to disclose their personal interest. The plaintiff seeks, among others, to recover the sum of USD 27 million from the 2nd and 3rd defendants.

[56] In its Statement of Claim (SOC), the plaintiff pleaded as follows:

(i) The defendants had induced the plaintiff to enter into the SPAs with full knowledge that the said transactions were to defraud the plaintiff;

(ii) The defendants induced the plaintiff to make a payment of USD5,000,000 by fraudulent misrepresentations;

(iii) The defendants had received payments via PT ASU and PT ASI as a result of the fraudulent act; and

(iv) The defendants had concealed the fact of the whereabouts of the proceeds of their fraud from the plaintiff.

[57] On 12 December 2014, the plaintiff filed an ex parte application (encl 48) against CIMB Bank Berhad and CIMB Islamic Bank Berhad (CIMB) for an order to allow the plaintiff to inspect and take copies of all entries in the books of the banks and all documents in CIMB's possession in relation to bank accounts belonging to the 1st defendant and third parties, PT Anglo Slavic Indonesia (PT ASI), Fast Global Investments Limited (Fast Global), PT Nusantara Rising Rich (PT NRR) and Telecity Investments Limited (Telecity). Enclosure 48 was filed pursuant to ss 6 and/or 7, BBEA and/or O 92 r 4 ROC.

[58] The basis of this application was a press statement dated 28 October 2014 which purportedly disclosed the flow of monies paid by the plaintiff pursuant to the SPAs, to PT ASI, PT NRR, Fast Global and Telecity.

[59] Enclosure 48 was allowed by the High Court on 25 June 2018 (BBEA Order 1) in the following terms:

(i) The plaintiff is at liberty to inspect and take copies of all entries in the books of CIMB relating to the bank accounts belonging to PT ASI, Fast Global, PT NRR, and Telecity. By this order, the plaintiff is given a blanket unlimited access to all information retained by the CIMB from the date the said bank account was opened with CIMB until the date of the BBEA Order 1;

(ii) The plaintiff is at liberty to inspect and take copies of all documents in CIMB's possession in relation to each of the bank accounts belonging to PT ASI, Fast Global, PT NRR, and Telecity; giving the plaintiff unlimited access to all documents of any nature that were in CIMB's possession from the date the said bank account was opened until the date of the BBEA Order 1; and

(iii) The plaintiff is at liberty to use any information obtained pursuant to BBEA Order 1 for the purposes of any legal proceedings ancillary to the Suit as the appellant deems appropriate. Thus, the use of the material so disclosed was not limited to the proceedings in the High Court.

[60] There are no written grounds of judgment by the High Court Judge giving reasons for his decision on encl 48.

[61] The plaintiff then filed another application against CIMB and Maybank Berhad on 18 October 2018 (encl 307) for an order to allow the plaintiff to, inter alia, inspect and take copies of all entries in the books of the banks as well as all documents in relation to bank accounts belonging to the defendants. Enclosure 307 was filed pursuant to s 6 and 7 BBEA and/or O 92 r 4 ROC.

[62] The basis of encl 307 was that the documents and information obtained pursuant to BBEA Order 1 were material to the plaintiff's case. In its supporting affidavit, the plaintiff's then Director of Corporate Finance deposed that BBEA Order 1 revealed further documentation in relation to the bank accounts and entries of PT ASI, Fast Global, PT NRR and Telecity. And that such information showed that these entities were in essence controlled and/or connected to and/or related to the defendants.

[63] It is further contended by the plaintiff that the entries in the books of Maybank Berhad and CIMB relating to the defendants' accounts and the documentation relating to the inflow and outflow of funds from the said accounts are extremely material to a critical issue in the plaintiff's claim. The information and documentation sought by the Order prayed for therein will reveal that the plaintiff's monies paid pursuant to the SPAs were eventually channeled into the defendants' accounts. The plaintiff, however, did not identify any of the documents sought as being "banker's book" entries within the meaning of s 2 BBEA.

[64] The defendants opposed encl 307 and argued that the application was misconceived in law for it being, in substance, an application for discovery against CIMB and Maybank Berhad. The plaintiff ought to have filed instead an application under O 24 r 7 ROC 2012. The plaintiff had not sought discovery against the defendants in respect of the said matters. The provisions in the BBEA could not be relied on to circumvent the strictures on discovery under the ROC. Furthermore, the orders sought are too wide and all encompassing, and oppressive. It is the defendants' argument that encl 307 is in effect a fishing expedition and an abuse of the process of the High Court.

[65] The High Court allowed encl 307 on 7 January 2019. Following clarification sought by the defendants, the orders granted under BBEA Order 2 were limited to allowing the plaintiff to inspect and make copies of entries made between 28 December 2012 to 22 September 2014. The BBEA Order 2 was stayed by the Court of Appeal on 14 February 2019. However, by that time the banks concerned had produced copies of some documents. Since the BBEA Order 2 had been stayed pending the determination of the appeals by the Court of Appeal, the defendants sought for the trial to be adjourned pending the determination of the appeals. The learned High Court Judge, however refused to adjourn and directed that the trial proceed. The plaintiff filed an application (encl 395) for the disputed documents to be admitted and/or taken as evidence and marked as exhibits pursuant to ss 2, 3, 4, 5 and/or 6, BBEA and/or O 92 r 4 ROC 2012.

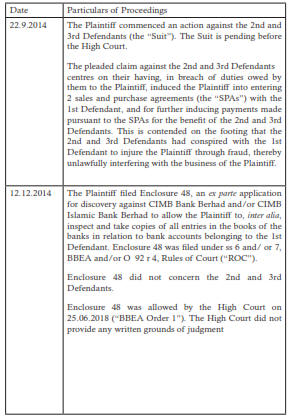

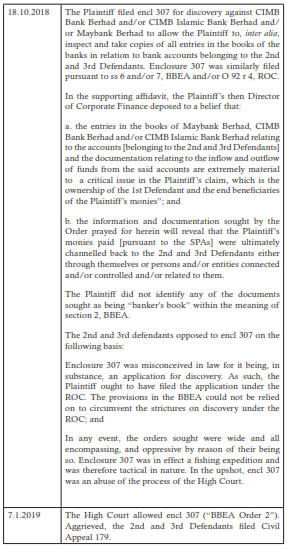

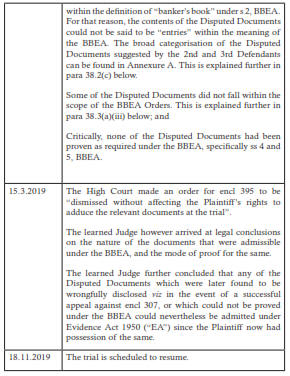

[66] The chronology of events have been articulately tabulated by the Court of Appeal through the written judgment of Kamaludin Md Said, COA Judge which I reproduced below for reference and better appreciation of the facts as well as the applications before the courts:

The High Court

[67] The learned High Court Judge made the following findings:

(i) In respect of encl 307, the learned High Court Judge was of the view that the BBEA provided an alternative and/or specific means of discovery in respect of banker's book. In determining whether to grant an order under s 7 of BBEA, the ordinary principles of discovery would be applicable. There was no need to comply with ss 4 and 5 of BBEA.

(ii) In respect of encl 395, any documents that were improperly disclosed pursuant to an order granted under s 7 of BBEA could nevertheless be admitted under the EA. There was no need to comply with ss 4 and 5 of BBEA as s 3 of the Act must be understood in the context of modern banking practice and the provisions of the EA.

(iii) In respect of BBEA Order 2, there was no necessity to comply with both ss 4 and 5 of BBEA as s 3 of BBEA must be understood in the context of modern banking practice and the provisions of the EA. If a document falls within the meaning of a banker's book as defined under s 2 BBEA, all that was required was a certificate tendered pursuant to s 90A(2) of EA. There was no need to comply with ss 4 and 5 of BBEA. Any documents that were improperly disclosed pursuant to an order granted under s 7 of BBEA could nevertheless be admitted under the EA.

The Court Of Appeal

[68] The Court of Appeal took a different view from the High Court. In respect of encl 307, the Court of Appeal agreed with the defendants that the BBEA was legislated specifically to facilitate the proving of banking transactions through the admission of bankers' evidence. It is not intended to serve as an alternative means of discovery against banks. It follows that the ordinary principles of discovery would not be applicable in an application under s 7 BBEA. Order 24 of the ROC 2012 provides a specific legal framework for discovery in Malaysia. The learned High Court Judge failed to specifically identify which of the disputed documents were or were not banker's book that is, disputed documents referred to documents purportedly obtained under BBEA Order 1 and documents purportedly obtained under BBEA Order 2. Documents such as company documents, memorandum or resolution for opening of bank account, memorandum or resolution for change of authorised signatory are not "banker's book" as they are not permanently record of transactions in the ordinary business of a bank.

[69] The Court of Appeal described in detail the different documents which can be categorised as banker's book. Miscellaneous internal documents used by the bank for example, specimen signature form, remittance application form, account opening application form, correspondence and documents evidencing the closing of account, are not "banker's book" as they do not permanently record transactions in the ordinary course of business of a bank.

[70] Cheques and paying-in slips, such as cheque deposit receipts, transaction slips are not "banker's book" as they do not permanently record transactions in the ordinary business of a bank. They are either instructions or documents evidencing the said instructions prepared for customers' convenience.

[71] Bank statements are not "banker's book" as they are created not for the purpose of permanently recording transactions in the ordinary business of a bank, but for customer's reference only.

[72] In respect of BBEA, the Court of Appeal opined that the plaintiff would not be permitted to adduce under the EA as the documents were improperly disclosed. Disputed documents should be excluded as there are outside the scope of the BBEA for not being copies of entries in banker's book within the meaning of s 2 BBEA. The plaintiff was required to prove and verify any of the disputed documents that fell within the permissible scope of the BBEA Orders under ss 4 and 5 of BBEA. Failing that, the plaintiff was not permitted to rely on the disputed documents based on the provision of the EA.

[73] In respect of BBEA Order 2, the plaintiff is required to prove and verify any of the disputed documents that fall within the required scope of the BBEA Orders under both ss 4 and 5 of BBEA. If the plaintiff fails to do so, the plaintiff is not permitted to rely on the disputed documents. Enclosure 395 ought to have been treated only as applying to copies of documents produced under BBEA Order 1, and that all the documents produced under BBEA Order 1 ought to have been regarded as inadmissible under the BBEA on the ground that those documents were not admissible under the EA.

The Legislative Framework

[74] The plaintiff's applications in the encls 307 and 395 were filed pursuant to the provisions of the BBEA and the inherent powers of the court under the ROC 2012. It is the plaintiff's argument that the provisions of the BBEA Order only provide a mechanism in which a document already obtained pursuant to a discovery application under O 24 r 7A of ROC 2012 may be proved at trial.

[75] In response, learned counsel for the defendants argued that the applications filed by the plaintiff were misconceived and an abuse of process. The court did not have the jurisdiction to grant the orders prayed for by the plaintiff.

[76] It would perhaps be more convenient and appropriate in this case to deal with the principles of law and discuss the legislation referred to by the parties in this appeal.

Rules Of Court 2012 (ROC 2012)

[77] Order 24 ROC provides the legislative procedure for discovery in proceedings in court. The application for discovery is a pre-trial procedure before the matter is set down for trial. Under O 24 r 3 ROC 2012 the court may at any time order any party to a cause or matter to give discovery by making and serving on any other party a list of the documents which are or have been in his possession, custody or power:

3. (1) Subject to the provisions of this rule and of rr 4 and 8, the Court may at any time order any party to a cause or matter (whether begun by writ, originating summons or otherwise) to give discovery by making and serving on any other party a list of the documents which are or have been in his possession, custody or power and may at the same time or subsequently also order him to make and file an affidavit verifying such a list and to serve a copy thereof on the other party.