Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Mohamad Zabidin Mohd Diah, Hadhariah Syed Ismail, Ahmad Nasfy Yasin JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: W-02(NCVC)(W)-1567-07-2018]

25 June 2021

Contract: Building contract - Claim for monies due under sub-contract - Respondent agreed to pay appellant monies due pursuant to terms of compromise agreement and settlement agreement - Terms of agreement, interpretation of - Whether there was no proper evaluation of evidence and pleadings by trial judge - Whether appellant proved its case and entitled to judgment

The present dispute between the parties arose from facts that occurred commonly in construction contracts. The respondent was appointed by Embassy Court Sdn Bhd ("Embassy Court") to carry out and complete piling and substructure works for a condominium project. The respondent subsequently appointed the appellant to carry out the piling works. Embassy Court then failed to make payment of monies due and owing to the respondent which resulted in the respondent terminating the contract with Embassy Court. The respondent proceeded to issue notice to the appellant informing the latter of the determination of the sub-contract work. The appellant, aggrieved with the non-payment of what it alleged as the amount due under the subcontract work, filed a claim against the respondent, claiming its entitlement for the works done up to termination. That proceeding was, however, stayed pending arbitration proceedings between Embassy Court and the respondent. Subsequently, the respondent succeeded in the arbitration proceedings and was awarded a sum of RM18,718,966.28. Premised on the arbitration award, the appellant and the respondent negotiated and agreed that the appellant would be paid a sum of RM6,121,660.34 and a Compromise Agreement was signed. The parties then signed a Settlement Agreement on similar terms as the Compromise Agreement. Subsequently, Embassy Court and its holding company, Magna Prima Berhad, and the respondent entered into a consent judgment, and it was agreed that a sum of RM16,000,000.00 was payable to the respondent by Embassy Court. This, in effect, reduced the sum payable to the respondent under the arbitration award. The appellant therefore claimed a sum of RM5,232,000.00 pursuant to the terms of the Settlement Agreement to be settled when the respondent received the instalment payments. According to the appellant, the respondent unilaterally reduced the amount payable to it to RM3,809,662.80 based on the calculation of 23.81% of RM16,000,000.00 and thereafter made payments by instalments on the reduced sums. The appellant said it objected to the unilateral reduction, but that did not stop the respondent from further reducing the appellant's entitlement another three times in succession. The appellant therefore claimed judgment in the sum of RM2,579,733.31 being the difference between the total amount due under the Settlement Agreement (RM5,232,000.00) and amounts already paid (RM2,652,266.69). The High Court Judge ("judge") ruled in favour of the respondent, resulting in the present appeal by the appellant. The core of the dispute laid in the interpretation of the terms of the Agreements in respect of the sum to be paid to the appellant by the respondent.

Held (allowing the appellant's appeal):

(1) There had been, on the facts, no proper evaluation of the evidence and pleadings by the judge. The conclusions reached by the judge were plainly wrong. The respondent's submissions on the existence of implied terms on the sharing of costs and expenses were not only misconceived but unsupported by evidence. In point of fact, cl 2 of the Settlement Agreement clearly provided that the amount payable by the respondent was equivalent to 32.70% of the amount under the arbitration award. Thus, applying the said formula when Embassy Court and the respondent agreed to settle at RM16,000,000.00, the appellant's portion at 32.70% should amount to RM5,232,000.00. As such, the respondent's contention that it was entitled to deduct the sum of RM2,660,538.84 as it was subject to the appropriate and proportionate adjustment clause militated against the weight of evidence. Clause 2 in both Agreements could not be unilaterally varied by the respondent based on its own interpretation which was clearly skewed towards it. Similarly, there was no appreciation by the judge of the evidence that the exchange of correspondence relied on by the respondent to show that the appellant had somehow agreed to a reduction and costs-sharing was nothing but an attempt to reach a compromise and could not displace the written Agreements executed by the parties. Further, it was clear that the negotiations were done on a "without prejudice" basis. The authorities on the scope and effect of "without prejudice" communications were aplenty and plain. In the present case, the "without prejudice" communication was also agreed to by the parties. Similarly, the fact that the appellant had at all times objected to the conduct of the respondent in unilaterally varying the amount payable had not been given sufficient attention, more so when that fact stood unchallenged by the respondent. Thus, a proper appreciation of the evidence would, on the balance of probabilities, point to the conclusion that the appellant had proved its case and was entitled to a judgment. (paras 35-40)

Case(s) referred to:

Balasingham v. Public Prosecutor [1959] 1 MLRH 585 (refd)

Dr Hari Krishnan & Anor v. Megat Noor Ishak Megat Ibrahim & Anor and Another Appeal [2018] 1 MLRA 535 (folld)

Ganapathy Rengasamy v. PP [1998] 1 MLRA 11 (refd)

Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 (folld)

Shirley Kathreyn Yap v. Malcom Thwaites [2016] 6 MLRA 171 (refd)

Tan Ah Tong v. Gee Boon Kee & Ors [2005] 2 MLRA 394 (folld)

Tan Kim Leng & Anor v. Chong Boon Eng & Anor [1974] 1 MLRA 147 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, s 71(1)

Counsel:

For the appellant: Harpal Singh Grewal (Reny Rao with him); M/s AJ Ariffin Yeo & Harpal

For the respondent: Sanjay Mohanasundaram (Gobinanth Karuppan with him); M/s Sanjay Mohad

JUDGMENT

Ahmad Nasfy Yasin JCA:

Introduction

[1] This is an appeal by the appellant, the plaintiff in the court below against the decision of the learned High Court Judge in dismissing the appellant's claim after trial.

[2] We have read the written submission and heard counsel for both parties.

[3] Having considered the materials placed before us in the records of appeal, we are satisfied that there are merits in the appeal. We accordingly and unanimously allowed the appeal. The following are our grounds in arriving at that decision.

Background Facts

[4] The dispute between the parties arose from facts that occurred commonly in construction contracts. It occurred in the following way. The respondent was appointed by Embassy Court Sdn Bhd on 12 July 2005 to carry out and complete the piling and substructure works for a condominium project located on part of Lot 305, Section 63, Lorong Kuda, Off Jalan Tun Razak, Kuala Lumpur. The value of this project was stated to be RM31,226,056.14. The respondent, subsequently on 30 August 2015, appointed the appellant to carry out the piling works. The value of the sub-contract between the appellant and the respondent is stated as RM10,041,468.61.

[5] Embassy Court Sdn Bhd then failed to make payment of monies due and owing to the respondent and this resulted in the respondent terminating the contract with Embassy Court Sdn Bhd on 20 January 2007. The respondent, subsequently proceeded to issue notice to the appellant informing the latter of the determination of the sub-contract work. That notice dated 20 January 2007, contained, among others, the following:

"We refer to the above sub-contract and the meeting held in our office today when we informed you that we have today exercised our right under the main contract to terminate our employment under the contract following a breach by the employer in failing to pay amounts due under interim payment certificates. Pursuant to cl 29 of the sub-contract your employment under the sub-contract is automatically determined as a consequence of our employment being terminated under the main contract."

[6] The appellant, aggrieved with the non-payment of what it alleged as the amount due under the sub-contract work, filed a claim against the respondent, vide Kuala Lumpur High Court No S-22-530-2009 claiming their entitlement for the works done up to termination. That proceeding, was however stayed pending arbitration proceeding between Embassy Court Sdn Bhd and the respondent.

[7] Subsequently, the respondent succeeded in the arbitration proceeding and was awarded a sum RM18,718,966.28 on 3 December 2012.

[8] Premised on the arbitration award, the appellant and the respondent negotiated and agreed that the appellant will be paid a sum of RM6,121,660.34 and a Compromise Agreement dated 15 February 2012 was signed. The parties then signed a Settlement Agreement on 3 July 2012 on similar terms as the Compromise Agreement.

[9] Subsequently, Embassy Court Sdn Bhd and its holding company, Magna Prima Berhad and the respondent entered into a consent judgment, and it was agreed that a sum of RM16,000,000.00 was payable to the respondent by Embassy Court Sdn Bhd. This, in effect, reduced the sum payable to the respondent under the arbitration award. It must be mentioned too that in the consent judgment the agreed sum was to be paid by instalment.

[10] The appellant therefore claimed a sum of RM5,232,000.00 pursuant to the terms of the Settlement Agreement to be settled when the respondent received the instalment payment from Magna Prima. The first instalment of RM430,000.00 was made on 18 September 2015.

[11] According to the appellant, on 12 October 2015, the respondent unilaterally reduced the amount payable to it to RM3,809,662.80 based on the calculation of 23.81% of RM16,000,000.00 and thereafter made payments by instalment on the reduced sums (first purported reduction).

[12] The appellant said it objected to the unilateral reduction, but that did not stop the respondent, who further varied the appellant's entitlement vide its letter dated 18 December 2015 reducing the entitlement to RM2,660,538.84 (second purported reduction).

[13] Despite the appellant objecting to this second purported reduction vide their letter dated 18 December 2015 the respondent further varied the sum to RM3,681,654.88 (third purported reduction).

[14] Around 21 June 2016, the respondent once again wrote to the appellant to further vary amount to RM3,006,665.80 (fourth purported reduction).

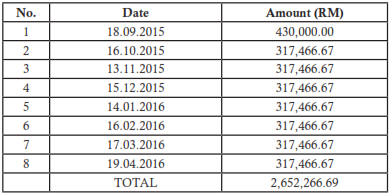

[15] It is not in dispute however that the respondent had made various payments as follows:

[16] The appellant therefore claimed judgment in the sum of RM2,579,733.31 being the difference between the total amount due under the Settlement Agreement (RM5,232,000.00) and amounts already paid (RM2,652,266.69).

At The High Court

[17] At the High Court, the learned judge after hearing the evidence and submissions of both parties ruled in favour of the respondent. Learned counsel for the appellant had referred us to the learned judge's brief decision read in open court as follows:

(i) Both the Compromise Agreement and the Settlement Agreement did not provide a specific mechanism/formula to determine the amount to be paid to the plaintiff in the event the amount paid to the defendant by Embassy Court is less than RM18,718,966.28.

(ii) There is no breach of the Settlement Agreement by the defendant as the amount of the plaintiff 's entitlement was not specified in the Settlement Agreement.

(iii) The parties have not agreed on the amount of the appropriate and proportional adjustment reflecting the final amount paid to the defendant for the corresponding costs under the main contract between Embassy Court and the defendant as stipulated in the Compromise Agreement.

(iv) The parties had entered into the Settlement Agreement with the understanding that the monies payable (if any) to the plaintiff by the defendant, are subject to the amount of monies that will be recovered by the defendant under the main contract with Embassy Court and the costs incurred by the defendant in the recovery of the monies.

(v) The costs incurred by the defendant in the recovery of the monies under the main contract with Embassy Court are the defendant's legal costs in the arbitration proceeding and not the costs for the construction works under the main contract for the project.

(vi) The parties were fully aware at the time they entered into the Settlement Agreement that the cost had not yet been awarded by the arbitrator and hence the issue of the amount of the costs of the arbitration proceeding was clearly within the contemplation of the parties when they entered into the Compromise Agreement as well as the Settlement Agreement.

(vii) The plaintiff had agreed to share 50% of the total legal cost incurred by the defendant in recovering the outstanding amount from Embassy Court, after it was explained to the plaintiff, at a meeting held on 7 December 2015 between the parties' respective representative. Thus, to ascertain the amount payable to the plaintiff, the total cost incurred by the defendant in recovering the outstanding amount from Embassy Court must be included.

[18] That, in short is how the matter came before us.

Preliminary Issue

[19] Learned counsel for the appellant begun the appeal by highlighting that the judge had retired on 31 July 2019 without furnishing any written grounds of the decision prior to retirement. This, according to learned counsel has deprived the appellant of ventilating all the issues raised in the Memorandum of Appeal.

[20] In short, the central focus of the attack mounted by the appellant is on the absence of or sufficiency of the judicial appreciation of the facts and evidence leading to the decision as there is nothing on record to show that that exercise had been undertaken.

[21] We consider it apposite at this juncture to address this issue of the absence of grounds of judgment, something that occurs more commonly now as compared to previously. In the first place, we should like to state that it is incumbent on any judge, having made a decision to provide grounds for the decision at the earliest, more so upon learning that an appeal had been filed. That is a given. For the strength of the decision lies in the reasoning and not the decision itself. It must be a speaking one (Balasingham v. Public Prosecutor [1959] 1 MLRH 585, Tan Kim Leng & Anor v. Chong Boon Eng & Anor [1974] 1 MLRA 147, Ganapathy Rengasamy v. PP [1998] 1 MLRA 11). No thunder is needed. It is a place where the language, instead of a voice, is raised, to borrow wise words from Rumi who said that it is the rain that grows flower and not the thunder. The grounds must stand scrutiny and reflects the basis upon which the decision was reached and reflect the thought processes that went in making that decision. Nothing must be left unsaid or said in coded signals as if litigants are signal readers equipped with code breakers and ready to decipher codes at will. Let no litigant wring their hands in the air and venting in frustrations said: My Lords, we are neither mind readers nor jailbreakers!

[22] In the second place we must also state that the absence of a written ground could not in all cases or ipso facto result in a new trial. That will be decided on case to case basis. A similar situation occurred before this court in Tan Ah Tong v. Gee Boon Kee & Ors [2005] 2 MLRA 394. There the following has occurred:

"[9]...There were no grounds of judgment, the trial judge having gone on retirement soon after delivering his judgment, without preparing them. In his submission in the appeal, the sole aim of learned counsel for the appellant (defendant 1), Mr Tommy Thomas, was to persuade the court of the need for a new trial of the action resulting from the absence of the judge's grounds of judgment. Counsel for the appellants in the other two appeals also participated in the hearing of appeal No 287 since if, on that appeal, a new trial was ordered the order would affect all parties. Since there was nothing else advanced in submission in support of the appeal, the result would be that if we disagreed with the plea for a retrial, the appeal must be dismissed.

[10] It was not Mr Tommy Thomas's contention that in law where no grounds of judgment are available for a civil appeal there must be a new trial. He had not been able to find any reported decision in Malaysia or England 'where absence or lack of grounds of judgment by a trial judge resulted in comments by an appellate court'. He could only rely on three cases where the grounds were available but there had been delay in their release or paucity of thinking in them and, he said, for either of those shortcomings the appellate court had criticized the court of first instance. The three cases are Tan Hun Wah v. Public Prosecutor and Another Appeal [1993] 1 MLRA 728 Flannery v. Halifax Estate Agencies Ltd [2000] 1 All ER 373 and English v. Emery Reimbold & Strick Ltd [2002] 2 All ER 385. It would follow, reasoned Mr Tommy Thomas, that the appellate court would harshly criticize a trial judge who did not at Tan Ah Tong v. Gee Boon Kee & Ors [2005] 2 MLRA 394 all produce his grounds of judgment (see paras 3 and 8 of his written submission). That may be so, but the question before us was not one of criticism but one of ordering a new trial. Justification for criticism need not also be justification for ordering a new trial."

[23] Rejecting the submissions of learned counsel for the appellant that "the absence of written reasons makes it 'impossible for an appellate court to determine how the trial judge discharged the vital function of appreciating evidence', his decision is 'unsafe' and because the decision is unsafe it is fitting and proper that a new trial be ordered under s 71(1) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964" as flawed reasoning this court, in that case, went on to state as follows:

"[12] Where, in an appeal in a civil matter, as in this appeal, reasons for the decision appealed against are not available, and not obtainable, the appeal, onerous though this may be, should proceed on an examination and assessment of the evidence to enable the appellate court to decide whether the evidence justifies the decision or otherwise. It will be as if the appellate court is sitting at first instance, except that the evidence is already before it. For reasons that are obvious or can easily be imagined, a new trial is undesirable and ought not to be ordered unless there is something crucial to a just decision in the case that can be established in the new trial but cannot be established on an assessment of the evidence. The evidence being all there already, such a thing must be very rare indeed. One that readily comes to mind is credibility in a situation where there is only the testimony of witnesses to rely on, being non-expert witnesses, and the testimony on one side appears to be equally cogent as the conflicting testimony on the other side. In such a case it may be said that a new trial is necessary so that the new trial judge will, as the appellate court will not, be able to observe the demeanour of the witnesses and credit the version of him whose demeanour is more reassuring. Even so, a correct decision may be frustrated if the opportunity to testify again gives to the witness whose testimony is not true an opportunity to improve his deportment."

[24] That passage we have stated above is in accord with our own views (which we gracefully adopt) and which in our judgment reflects the correct legal position. It is to be noted that that passage had received the endorsement of the Federal Court in Dr Hari Krishnan & Anor v. Megat Noor Ishak Megat Ibrahim & Anor and Another Appeal [2018] 1 MLRA 535. In the present case, we do not consider that it is appropriate for us to order a re-trial. Tempted as we are to offer criticism against the learned judge we find that discretion is the better part of valour. Onerous as it is we proceeded to consider and evaluate the evidence and the arguments very carefully.

The Appellant's Submission On Merits

[25] In addition, learned counsel also raised the following:

(i) The eight common issues agreed to be tried (see pp 105-107 of the Rekod Rayuan (Bahagian A) were not considered at all.

(ii) The learned judge has failed to appreciate or misunderstood the appellant's pleaded case as there is no indication at all whether the learned trial judge had considered the evidence and the pleadings.

(iii) The learned judge cannot be said to have undertaken an evaluation or analysis of the plaintiff 's pleaded cause of action to ascertain whether the pleaded cause of action had indeed been made out and proved.

(iv) The learned judge, in the absence of any evaluation of the evidence, could not be said to have made a proper finding of facts and this was plainly wrong as there is no indication whether there was sufficient judicial appreciation of the evidence; and

[26] To buttress its case the appellant had made a plethora of submissions. We trust we would not be doing an injustice to learned counsel by summarising the submissions as follows:

(a) The crux of the appellant's pleaded case against the respondent is that the respondent had breached the Settlement Agreement, which stipulated that the terms of the Compromise Agreement are incorporated into the Settlement Agreement.

(b) The appellant's sole witness Dr Soh Chee Hoon, the Managing Director of the appellant, who had full knowledge of the transactions between the parties had testified that pursuant to cl 2 of the Settlement Agreement the amount payable by the respondent shall be equivalent to 32.70% of the amount received by the respondent from Embassy Court from the arbitration award of RM18,718,966.28.

(c) Notwithstanding the arbitration award, Embassy Court and the respondent had agreed to a further compromise whereby the respondent agreed to accept the sum of RM16,000,000.00 and the appellant's portion being set at 32.70% would translate to RM5,232,000.00.

(d) The respondent unilaterally attempted to reduce the payment to the appellant to a percentage of 23.81% of the amount received by the respondent. This is referred to as the 1st reduced amount which was followed by 2nd reduced amount, 3rd reduced amount and 4th reduced amount.

(e) The respondent's interpretation of the Settlement Agreement that the appellant must bear 50% of the legal costs incurred in all the litigation against Embassy Court is misconceived.

(f) The appellant denied the Settlement Agreement provided for a reduction of a sum payable by the respondent. If at all that a reduction is to take place, it will only be applicable if the sum awarded by the arbitrator is varied.

(g) The only variation to the arbitration award was the reduction to a sum of RM16,000,000.00 which Embassy Court agreed to pay to the respondent and consequently, the appellant's entitlement will be reduced but nevertheless will be premised on 32.70% of the said sum.

(h) The appellant also submitted, that at any rate, the Compromise Agreement dated 15 February 2012 and/or the Settlement Agreement dated 3 July 2012 were illegal as they are champertous.

The Respondent's Submission

[27] The respondent contended that the appellant's pleaded case is not supported and is inconsistent with the contemporaneous documents submitted by the parties. In addition, there are two other issues that arose in the dispute between the parties. They are:

(a) Whether by the terms of the Settlement Agreement reached between the parties, the respondent is entitled to deduct the costs incurred by it in recovering the monies from Embassy Court Sdn Bhd.; and

(b) Whether an adjustment must be made to the amount payable to the appellant by the respondent depending on the amount recovered by the respondent from Embassy Court Sdn Bhd.

[28] It is submitted that the Statement of Claim filed on 22 July 2016, the appellant had specifically alleged in para 35 that it is entitled to the sum of RM2,579,733.31 but the appellant did not pray for any other sum or damages to be assessed or determined by the court. The appellant has failed to prove that it is entitled to any monies or a different sum. In addition, The appellant failed to plead for damages to be assessed. Thus, on the strength of the case of Shirley Kathreyn Yap v. Malcom Thwaites [2016] 6 MLRA 171 the learned judge was correct in dismissing the appellant's claim as the claim falls to be decided based on the evidence produced by the parties and the appellant had failed to prove that there is an agreement reached between the parties for the respondent to pay the sum of RM2,579,733.31.

[29] It was further submitted that following the award by the arbitrator the appellant and the respondent entered into what the respondent called an interim agreement. However, this was subject to an appropriate and proportional adjustment reflecting the final amount paid to the respondent under the main contract. It is further agreed that the respondent is only obliged to make payment after receiving payment from Embassy Court Sdn Bhd. In short, the arrangement is what is known in the industry as back-to-back payment. The appellant's witness, SP1, admitted that the amount payable to the appellant is subject to an appropriate and proportional adjustment.

[30] The respondent further submitted that the Compromise Agreement dated 15 February 2012 had referred to the costs incurred and intended for the same to be deducted from the total amount received from Embassy Court Sdn Bhd before deciding on the amount to be apportioned. Thus, the appellant has to bear a portion of the legal costs incurred by the respondent and further an adjustment has to be made based on the final sum received by the respondent from Embassy Court Sdn Bhd.

[31] Therefore, based on the terms of the respective agreements dated 15 February 2012 (Compromise Agreement) and 3 July 2012 (Settlement Agreement) the appellant had clearly agreed to accept a lower sum.

[32] It was highlighted to us that the amount of RM317,466.67 is precisely the amount as stated in the respondent's email dated 12 October 2015 representing the 23.81%. The respondent did exactly what was confirmed by the appellant in its letter dated 9 December 2015. Therefore, clearly the respondent was not in breach of the Settlement Agreement.

Our Decision

[33] From the above it is apparent that the facts are largely undisputed more particularly on events leading to the execution of the Compromise as well as the Settlement Agreement.

[34] The core of the dispute lies in the interpretation of the terms of the Agreements in respect of the sum to be paid to the appellant by the respondent. The core questions are, first, whether an adjustment can be made based on the actual amount recovered by the respondent under the main contract; and secondly whether the costs incurred by the respondent in the recovery of sums claimed under the main contract must also be borne by the appellant.

[35] We agree with the submissions of learned counsel for the appellant that there had been no proper evaluation of the evidence and pleadings by the learned judge resulting in the error of the findings of the judge. The Federal Court recently had the occasion to examine the circumstances under which an appellate intervention is required in the case of Ng Hoo Kui & Anor v. Wendy Tan Lee Peng & Ors [2020] 6 MLRA 193 where having examine the position in the UK as well as in Malaysia, Zabariah FCJ, delivering the judgment for the court stated:

[74] Thus, whilst there is a slight difference in approach of appellate intervention, both the UK Supreme Court and our Federal Court effectively share a common thread where it has been held that appellate intervention is justified where there is lack of judicial appreciation of evidence.

[36] It bears stating too that in the earlier part of the judgment of the Federal Court the following passages are important:

"[71] From the aforesaid authorities, there appears to be a difference in approach taken and applied by the UK Supreme Court and the approach taken by the Malaysian courts. Whilst Lord Reed in Henderson (supra) separated the four non exhaustive identifiable errors of a trial judge from the plainly wrong test:

(i) a material error of law;

(ii) a critical finding of fact which has no basis in the evidence;

(iii) demonstrable misunderstanding of relevant evidence; and

(iv) a demonstrable failure to consider relevant evidence;

(all of which justifies appellate intervention of a trial judge's decision), this court in Gan Yook Chin (supra) effectively included them under what amount to the trial judge as being "plainly wrong".

[72] The phrase "lack of judicial appreciation of evidence" used in Gan Yook Chin (supra) could very well encompass three out of four errors of a trial judge (other than the "material error of law") said to be identifiable by Lord Reed in Henderson (supra), namely:

(i) critical factual finding which has no basis in evidence;

(ii) demonstrable misunderstanding of relevant evidence; and

(iii) demonstrable failure to consider relevant evidence.

[73] Given that the issue at present is about identifying situations where the findings of fact by a trial court justify appellate intervention, the other identifiable error of "material error of law" listed by Lord Reed in Henderson (supra) can occur when a trial judge erroneously apply legal principles (eg rules of evidence) in the course of making a finding of fact, thus resulting in a lack of judicial appreciation of evidence. For example, when a trial judge erroneously placed a burden of proof on a party that will lead the judge to misdirect himself when he attempts to interpret the factual matrix before him. The commission of material error of law by the trial judge in arriving at his conclusions (eg the requirement of proof of intention in constructive trust as opposed to express trust), also justifies an appellate court reversing such conclusions."

[37] Having examined the facts and records we find that the conclusions reached by the learned judge are plainly wrong.

[38] We find that the respondent's submissions on the existence of an implied term on the sharing of costs and expenses are not only misconceived but unsupported by evidence. In point of fact, cl 2 of the Settlement Agreement clearly provides that the amount payable by the respondent is equivalent to 32.70% of the amount under the arbitration award. Thus, applying the said formula when Embassy Court and the respondent agreed to settle at RM16,000,000.00 and the appellant's portion at 32.70% would amount to RM5,232,000.00. As such, we are of the view that the respondent's contention that the respondent was entitled to deduct the sum of RM2,660,538.84 as it was subject to the appropriate and proportionate adjustment clause militates against the weight of evidence. Clause 2 in both Agreements, in our view, could not be unilaterally varied by the respondent based on its own interpretation which is clearly skewed to it.

[39] Similarly we find that there is no appreciation by the learned judge of the evidence that the exchange of correspondence relied on by the respondent to show that the appellant has somehow agreed to a reduction and costs sharing are nothing but an attempt to reach a compromise and cannot displace the written Agreements executed by the parties. Further it is as plain as a pikestaff that the negotiations were done on a "without prejudice" basis. The authorities on the scope and effect of "without prejudice" communications are aplenty and plain and we do not think we could add any further on the subject. In the present case the "without prejudice" communication was also agreed by the parties in the agreed facts. Similarly, the fact that the appellant had at all times objected to the conduct of the respondent in unilaterally varying the amount payable had not been given sufficient attention more so when that fact stood unchallenged by the respondent.

[40] In our view a proper appreciation of the evidence would, on the balance of probabilities, point to the conclusion that the appellant had proved its case and is entitled to a judgment.

Conclusion

[41] Based on the aforesaid reasons, curial intervention is required, and we accordingly do so. The appeal is therefore allowed to the extent stated below.

[42] The order of the High Court of 28 June 2018 is hereby set aside. We enter judgment for the appellant. We further order that the interest as claimed in para 35.3 of the Statement of Claim is to run from the date of the Writ.

[43] Taking into account the facts and submissions filed we award costs here and below to the appellant in the sum of RM50,000.00 subject to allocator fees. We so order.