Court of Appeal, Putrajaya

Hamid Sultan Abu Backer, Hanipah Farikullah, Kamaludin Md Said JJCA

[Civil Appeal No: W-02(IPCV)(W)-383-02-2019]

20 January 2020

Trade Marks: Infringement of registered trade marks and passing off - Likelihood of confusion or deception - Claim that corporate names of defendants infringed plaintiffs' trade mark - Whether defendants' corporate names resembled plaintiffs' registered trade marks and likely to deceive or cause confusion - Whether defendants were riding on goodwill of plaintiffs' trade mark - Whether plaintiffs' claim for passing off made out - Whether there was unlawful interference with trade of plaintiffs - Trade Marks Act 1976, ss 3(1),(2), 38(1)(a), (b), (c)

This was the plaintiffs' appeal against the High Court's decision which dismissed the plaintiffs' claims against the defendants for trade mark infringement, passing off and unlawful interference with trade. The plaintiffs were the registered owner of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks and claimed that the word "SkyWorld" was a prominent feature of the plaintiffs' trade marks. In this appeal, the issues to be decided were: (i) whether the defendants' names which resembled the plaintiffs' SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks could be held liable for trade mark infringement in respect of the use of the plaintiffs' trade marks; (ii) whether the defendants were trying to ride on goodwill of the plaintiffs' trade marks; (iii) whether the plaintiffs' claim for passing off was made out; and (iv) whether there was unlawful interference with trade of the plaintiffs.

Held (allowing the plaintiffs' appeal with costs):

(1) It was trite that a plaintiff in an infringement action was not required to establish that the infringing mark was identical. It would suffice for the plaintiff to establish that the infringing mark so nearly resembled the registered trade mark as was likely to deceive or cause confusion. In this instance, the 1st plaintiff had established s 38(1)(a), (b) and (c) of the Trade Marks Act 1976 ("TMA"). Further, the use of the infringing names by the defendants was likely to cause confusion or deception as the infringing names were aurally and visually similar to the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks. Therefore, the defendants had used the infringing names as trade marks in the course of their trade as defined under s 3(1) and (2) TMA. (paras 64-65)

(2) Based on the evidence adduced, the plaintiffs had established all the elements constituting trade mark infringement under s 38 TMA. Consequently, the defendants were liable for trade mark infringement in respect of their use of the mark/word resembling the plaintiffs' trade marks in the company names, domain name and project name. (para 74)

(3) The plaintiffs had adduced incontrovertible evidence in establishing that the legitimacy of the Sky World City Sabah project was suspected and that the police were investigating the developer's activities which were believed to be a fraud. Accordingly, the defendants were not genuine traders and were in fact tortfeasors attempting to ride on the plaintiffs' goodwill in the SkyWorld names and marks. The defendants had used the infringing names and marks to prey on unsuspecting investors to invest in a project that was not approved by the relevant authorities. In this regard, the trial judge had erred in failing to appreciate the above crucial evidence adduced when dismissing the plaintiffs' claim. (paras 95-96)

(4) The trial judge failed to appreciate that the plaintiffs' claim in passing off stemmed from the defendants' adoption of the SkyWorld names and marks, and was not only confined to the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks. It was trite law that a claim in passing off could be grounded on the defendants' misrepresentation arising from the use of a confusingly similar corporate or trade name. In the present case, the plaintiffs had acquired the requisite and sufficient goodwill in the SkyWorld names and marks through their extensive and substantial advertising and promotional activities and investments. On the other hand, the defendants had clearly failed to discharge their obligation to ensure that no confusion would arise from the use of the infringing names or marks. (paras 103-106)

(5) As the plaintiffs had established their claim for trade mark infringement and/or passing off, it was a natural consequence that the tort of unlawful interference with trade was also made out. (para 107)

Case(s) referred to:

Adam Opel v. Autec AG [2007] ECRI-0000 (refd)

AG Spalding Brothers v. AW Gamage, Ltd [1914-1915] All ER Rep 147 (refd)

Ahmad Najib Aris v. PP [2009] 1 MLRA 58 (refd)

Al-Baik Fast Food Distribution Co SAE v. El Baik Food Systems Co SA & Another Appeal [2016] 6 MLRA 268 (refd)

Al-Baik Fast Food Distribution Co SAE v. El Baik Food Systems Co SA [2016] 4 MLRH 361 (refd)

Anheuser-Busch v. Budejovicky Budvar, narodni podnik [2004] EUECJ C-245/02 (refd)

Arsenal Football Club [2002] ECR I-10273 (refd)

Aspect Synergy Sdn Bhd v. Banyan Tree Holdings Ltd [2008] 4 MLRH 347 (refd)

Avnet Inc v. Isoact Ltd [1998] FSR 16 (refd)

Ayamas Convenience Stores Sdn Bhd v. Ayamas Sdn Bhd [1994] 3 MLRH 222 (refd)

Beautimatic Inernational Ltd v. Mitchell International Pharmaceutical Ltd and Another [2000] FSR 267 (refd)

CDL Hotels International Ltd v. Pontiac Marina Pte Ltd [1998] 2 SLR 550 (refd)

Celine SARL v. Celine SA [Case C-17/06] (refd)

Clinique Laboratories, LLC v. Clinique Suisse Pte Ltd and Another [2010] 4 SLR 510 (refd)

Compagnie Generale Des Eaux v. Compagnie Generale Des Eaux Sdn Bhd [1996] 1 MLRH 282 (refd)

Consitex SA v. TCL Marketing Sdn Bhd [2008] 2 MLRH 380 (refd)

Danone Biscuits Manufacturing (M) Sdn Bhd v. Hwa Tai Industries Bhd [2010] 1 MLRH 76 (refd)

Dun & Bradstreet (Singapore) Pte Ltd & Anor v. Dun & Bradstreet (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [1993] 1 MLRH 211 (refd)

Elba Group Sdn Bhd v. Pendaftar Cap Dagangan Dan Paten Malaysia & Anor [1998] 1 MLRH 697 (refd)

Ellora Industries v. Banarsi Das Goela and Drs AIR 1980 Delhi 254 (refd)

Excelsior Pte Ltd v. Excelsior Sport (S) Pte Ltd [1985] 2 MLRH 434 (refd)

F&NDairies (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v. Tropicana Products, Inc and Other Appeals [2013] 6 MLRA 558 (refd)

Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v. Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] 118 IPR 239 (refd)

Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1 (refd)

Gnanasegaran Pararajasingam v. Public Prosecutor [1995] 2 MLRA 555 (refd)

Hew Chai Seng (T/A Pertiland Trading Co) v. Metronic Integrated System Sdn Bhd & Anor [2016] MLRHU 1566 (refd)

Ho Tack Sien & Ors v. Rotta Research Laboratorium SPA & Anor, Registrar of Trade Marks (Intervener) & Another Appeal [2015] 3 MLRA 611 (refd)

Hu Kim Ai & Anor v. Liew Yew Thoong [2005] 4 MLRH 718 (refd)

Insight Radiology Pty Ltd v. Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2016] 122 IPR 232 (refd)

Intel Corporation v. Intelcard Systems Sdn Bhd & Ors [2003] 3 MLRH 668 (refd)

Low Chi Yong v. Low Chi Hong & Anor [2017] 6 MLRA 412 (refd)

Megnaway Enterprise Sdn Bhd v. Soon Lian Hock (No 2) [2009] 2 MLRH 82 (refd)

Mesuma Sports Sdn Bhd v. Majlis Sukan Negara Malaysia; Pendaftar Cap Dagangan Malaysia (Intervener) [2015] 6 MLRA 331 (refd)

Mutiara Rini Sdn Bhd v. The Corum View Hotel Sdn Bhd [2015] MLRHU 1013 (refd)

Panhard v. Panhard [1901] 18 RPC 405 (refd)

Poddar Tyres Ltd v. Bedrock Sales Corporation Ltd [1993] AIR 237 (refd)

Re Pianotist Co's Application [1906] 23 RPC 774 (refd)

Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v. Borden Inc [1990]1 WLR 491 (refd)

Revertex Ltd & Anor v. Slim Rivertex Sdn Bhd & Ors [1989] 3 MLRH359 (refd)

Robelco v. Robeco Groep [2002] EUECJ C-23/01 (refd)

Saville Perfumery Ltd v. June Perfect Ltd [1941] 58 RPC 147 (refd)

Seet Chuan Seng & Anor v. Tee Yih Jia Food Manufacturing Pte Ltd [1994] 1 MLRA 68 (refd)

Sinma Medical Products (M) Sdn Bhd v. Yomeishu Seizo & Co Ltd [2004] 1 MLRA 691 (refd)

Standard Chartered Bank v. Mukah Singh [1996] 4 MLRH 438 (refd)

Syarikat Wing Heong Meat Product Sdn Bhd v. Wing Heong Food Industries & Ors [2009] 1 MLRH 947 (refd)

The Commissioners of Inland Revenue v. Muller & Co's Margarine Ltd [1901] AC 217 (refd)

The Eastman Phtographic Materials Company, Ltd v. The John Griffiths Cycle Corporation Ltdand the Kodak Cycle Company Ltd [1898] 15 RPC 105 Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v. Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 350 (refd)

Tong Guan Food Products Pte Ltd v. Hoe Huat Hng Foodstuff Pte Ltd [1991] 1 MLRA 555 (refd)

Trinity Group Sdn Bhd v. Trinity Corporation Berhad [2012] MLRHU309 (refd)

White Hudson & Co v. Asian Organization Ltd [1964] 1 MLRA 572 (refd)

Yong Sze Fun & Anor v. Syarikat Zamani Hj Tamin Sdn Bhd & Anor [2012] 2 MLRA 404 (refd)

Yong Teng Hing B/S Hong Kong Trading Co & Anor v. Walton International Limited [2012] 6 MLRA 629 (refd)

YouView TV Ltd v. Total Ltd [2012] EWHC 3158 (refd)

Y-TEQ Auto Parts (M) Sdn Bhd v. X1R Global Holding Sdn Bhd & Anor [2017] 2 MLRA 73 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Companies Act 1965, s 22

Companies Act 2006 [UK], s 69

Companies Act 2016, ss 15, 25(2), 26(1)(a), (b), (c), (2), 29

Evidence Act 1950, ss 90, 90A(2), (4)

Trade Marks Act 1976, ss 3(1), (2), 38(1)(a), (b), (c), 40(1)

Trade Marks Act 1994 [UK], s 10(4)(ce), (d), (e)

Other(s) referred to:

Augustine Paul , Evidence Practice and Procedure, 2nd edn, p 640

P Narayanan, Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off, 6th edn, pp 559-560

Trade Marks Directive [Directive 89/104/EEC] of 21 December 1988, arts 5(1), 6(1)(a)

Counsel:

For the appellants: Teo Bong Kwang (CW Wong & Eugene Ee Fu Xiang with him); M/s Chan Haryaty

For the respondent: Bani Prakash (Santhi, Deva Premila & Sheila Menon with him); M/s S San & Co

[For the High Court judgment, please refer to SkyWorld Development Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Skyworld Holdings Sdn Bhd & Ors [2019] 2 MLRH 480]

JUDGMENT

Kamaludin Md Said JCA:

Introduction

[1] This is the appellants/plaintiffs' appeal against the whole of the High Court's decision which dismissed the appellants/plaintiffs' claims against the respondents/defendants for trade mark infringement, passing off and unlawful interference with trade.

[2] The parties shall hereinafter be referred to as they were at the High Court.

[3] The plaintiffs are the registered owner of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks in Class 37 as follows:

[4] The plaintiffs claim that the word "SkyWorld" is a prominent feature of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks. In addition, the word "SkyWorld" forms part of the plaintiffs' company names and started using the "SkyWorld" Marks in 2014.

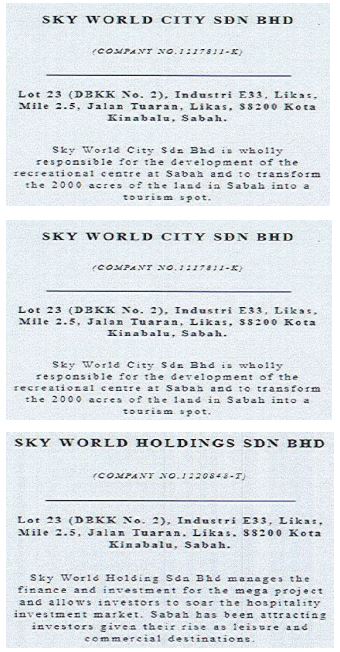

[5] The 1st to 4th defendants (Corporate Defendants) were all incorporated in 2017. The Corporate Defendants have been using the marks/words "Skyworld" and "Sky World" in relation to their company names, domain name as well as for their purported "Sky World City Sabah" project.

[6] The plaintiffs brought an action against the Corporate Defendants for using the marks/words "Skyworld" and "Sky World" in relation to their company names, domain name as well as for their purported "Sky World City Sabah" project. Hence, the defendants' corporate names had infringed the plaintiff's registered trade marks "SkyWorld". In addition, plaintiffs claim against the defendants for passing off the plaintiffs business, products and/or services by the use in the course of trade of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks, Names, Website and Domain Name and unlawful interference with trade.

[7] At the High Court, the plaintiffs' case is essentially that the defendants' corporate names and website domain name are infringing in that they so nearly resemble the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks as are likely to deceive or cause confusion in the course of the defendants' carrying out their business of developing the Sky World City project. The learned judge had dealt with the plaintiffs' claim in a full trial and delivered his decision in favour of the defendants. The grounds of judgment are found at pp 30 to 88 in Rekod Rayuan (Jilid 1-Bahagian A).

Decision Of The High Court

[8] The issue in this case is whether the defendants have used the plaintiffs' trade marks in the course of trade without consent and the unlawful usage of the trade marks owned by the plaintiffs has caused deception or confusion among the prospective customers. It is the plaintiffs' case that the defendants' corporate names and website domain name are infringing in that they so nearly resemble the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks as are likely to deceive or cause confusion in the course of the defendants' carrying out their business of developing the Sky World City project.

[9] The learned judge ascertained the deception or confusion of trade marks based on the case of Consitex SA v. TCL Marketing Sdn Bhd [2008] 2 MLRH 380 which had cited Parker J's decision in the well-known case of Re Pianotist Co's Application [1906] 23 RPC 774. The test in determining whether a mark is 'likely to deceive or cause confusion' is to judge the two words by their look and by their sound and considered all the surrounding circumstances.

[10] The Federal Court case of Yong Teng Hing B/S Hong Kong Trading Co & Anor v. Walton International Limited [2012] 6 MLRA 629 held that it is sufficient if the result of the registration of the mark will be that a number of persons will be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products came from the same source. Further, the more well-known or unusual a trade mark, the more likely is that consumers might be confused into believing that there is a trade connection between goods or services bearing the same or a similar mark.

[11] Further, the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks are composite marks and one of them is a stylish verbal mark visually comprising of the word SkyWorld (specifically with the letters "S" and "W" spelt in uppercase letter) with a stroke underneath the word "Sky" together with the phrase "design the experience". The other one of them has the same characteristics but with additional four Chinese characters underneath the phrase "design the experience".

[12] The learned judge found that there is no resemblance between them whatsoever. The principal similarity is in the defendants' corporate names and domain name and the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks arising from the word "Skyworld" audibly. In other words, the plaintiffs' contention is that the "Skyworld" and "Sky World" marks are the defendants' corporate names and domain name however the learned judge saw that they are visually different because the defendants' corporate names in their business documents as well as their web site domain name used the word "Skyworld" either wholly in uppercase or lowercase but not in mixed uppercase and lowercase as in the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks.

[13] The learned judge made an observation that the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks "SkyWorld" are not registered as word marks which might have otherwise conferred monopoly on them on the word "Skyworld". He was of the further view from the evidence adduced by the plaintiffs in their projects advertisement that the dominant mark in the Trade Names used by them is the only the word "Sky" with a wavy underline beneath it as seen in all their project names SkyArena, SkyAwani, and etc.

[14] In ascertaining whether there has been the likelihood of deception or confusion is depending on the all the circumstances of each case, the learned judge had referred to several authorities put forth before him and his position was that it centred on the degree of similarness as well as the associated business usage of the marks especially the consumer knowledge and association with them. The test is objective one (see the Singapore Court of Appeal case of Tong Guan Food Products Pte Ltd v. Hoe Huat Hng Foodstuff Pte Ltd [1991] 1 MLRA 555 which had been followed by the Court of Appeal in Yong Sze Fun & Anor v. Syarikat Zamani Hj Tamin Sdn Bhd & Anor [2012] 2 MLRA 404. It was also held that it is sufficient that a substantial proportion of persons who are probably purchasers of the goods of the kind in question would in fact be confused. Whether or not there is misrepresentation is always a question of fact to be determined by the court in the light of evidence of surrounding circumstances. The impression is entirely a matter for the judgment of the Court and not that of the witnesses.

[15] As to the similarity in the trade marks audibly and hence likely tendency to cause deception or confusion, the learned judge relied on the Brunei High Court case of Ayamas Convenience Stores Sdn Bhd v. Ayamas Sdn Bhd [1994] 3 MLRH 222, where Deny Roberts CJ held that it is not sufficient only to show that a company has been registered with a name similar to a trade mark (though this was not the same, as there has been no use of the chicken logo). It is necessary to show an actual or likely infringement. This the plaintiff has failed to do.

[16] In this case it is not disputed the word "Skyworld" is identical audibly based on the test enunciated in The Pianist Co Ltd Application. In the Supreme Court case of Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v. Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 350, there are two features of the two marks which are similar, namely, red in colour and split in wording'. However, having regard to the totality of the circumstances of the case, the learned judge was apparently satisfied that there is no similarity between the two words 'MISTER' and 'SISTER' as to be likely to cause deception or confusion. The words are different. There is similarity in the second syllable but as a whole the similarity is not close enough as to be likely to cause deception or confusion. Further, the get-up of the intervener's product is green background colour with the picture of a lady whereas the get-up of the applicant's product is white-blue-grey background colour with the picture of a lady and a man. The learned judge was of the opinion that the Tohtonku case did not lay down the proposition that there is overriding conclusion of infringement if the words are identical. It instead suggested that the marks must be compared as a whole, both audibly and visually. This was likewise done in the later celebrated trade mark cases of Danone Biscuits Manufacturing (M) Sdn Bhd v. Hwa Tai Industries Bhd [2010] 1 MLRH 76 as well as Elba Group Sdn Bhd v. Pendaftar Cap Dagangan Dan Paten Malaysia & Anor [1998] 1 MLRH 697 where the marks are audibly similar.

[17] In this case, the learned judge was satisfied that the word 'Skyworld' phonetically per se is the essential or striking feature of the plaintiffs' marks. He went on to consider the business activity of the parties in determining whether the average discerning consumer could be misled by associating one with the other. The 1st plaintiff is basically involved in the business of real estate property development. From the documentary evidence produced by the plaintiffs, they develop residential properties primarily in the Klang valley, West Malaysia for sale to the public pursuant to the Housing Development Act 1966. The plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks are also registered in Class 37 accordingly.

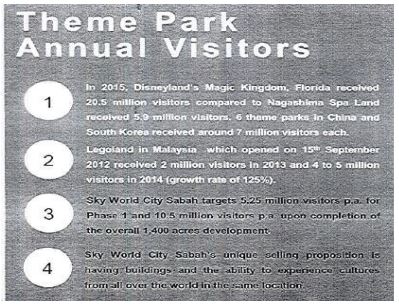

[18] The defendants on the other hand are involved in the business of tourism and is presently embarking on its maiden Sky World City project in Karambunai, Sabah, East Malaysia. From the documentary evidence produced by the defendants, the Sky World City project is a tourism theme park project. It has been described by the defendants as (a universal theme park that features replicas of landmarks and iconic buildings from countries around the globe. Visitors will be able to relive their travel experiences thorough each individual pavilions.

[19] The learned judge considered the defendants' business that despite there are residential accommodation buildings planned to be built in the Sky World City project, he found there are probably hotels to accommodate the tourists but not buildings for sale to the public. He also took into account that the 5th defendant applied to register the defendants' 'S' Trade Mark in various classes but not in Class 37. The 5th defendant on 23 April 2018 applied to register the following trade mark in Classes 9, 16, 28, 35, 36, 38, 41, 42, 43 and 44:

[20] Based on that fact, the learned judge concluded that the prospective customers of the plaintiffs and defendants amongst the public at large are not likely to be deceived or confused by reason of the stark difference in the business of the respective parties. He held that the imperfect recollection of these customers is neither relevant nor cogent here as far as the Trade Name is concerned. Likewise, it was found that there was no confusion in the case of Aspect Synergy Sdn Bhd v. Banyan Tree Holdings Ltd [2008] 4 MLRH 347 because the characteristics of purchasers of residential units there were different. The cases of Sinma Medical Products (M) Sdn Bhd v. Yomeishu Seizo & Co Ltd [2004] 1 MLRA 691 and Trinity Group Sdn Bhd v. Trinity Corporation Berhad [2012] MLRHU 309 amongst several others relied by the plaintiffs were distinguished on the facts particularly because the parties were competing in the same business and marketplace. In those circumstances, the learned judge was satisfied and found the defendants' corporate names and domain name as used in connection with the Sky Wold City project are unlikely to deceive and cause confusion in the course of trade in which the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks are registered. A similar result was achieved in the Ayamas case.

[21] The learned judge had also considered the two e-mails adduced by the plaintiffs from a Gopal and a John Smith in attempting to show that the public was actually confused. However, both Gopal and John Smith were not called as witnesses at the trial and the learned judge accordingly drew reasonable inferences from the circumstances relating to the document including the manner and purposes of its creation as well as accuracy pursuant to s 90 of the Evidence Act 1950. He found the e-mails dubious because the e-mails are perfunctory and without disclosure of their relationship with the plaintiffs. It appears to him to be merely two busy-bodies. Accordingly, he discarded both e-mails.

[22] The learned judge was of the view that if the plaintiffs had intended to show there was actual confusion, it would have been more cogent for the plaintiffs to appoint an independent consultant to undertake a market survey and analysis of the state of affairs relating to confusion based on an adequately acceptable sample size. Consequently, the learned judge held that the plaintiffs particularly the 1st plaintiff who is the only plaintiff that has legal standing to sustain the cause of action of trade mark infringement has not proved that the defendants have infringed the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks pursuant to s 38 of the Trade Marks Act 1976 (TMA). He also held that the adoption and hence usage of "Skyworld" by the parties for purposes of their corporate names as well as project name was in fact coincidental. The defendants did not purposely adopt the same to imitate or interfere with the plaintiffs' business and what more; by way of unlawful means. Finally, it is the learned judge's decision that in this case there should be concurrent use of trade name in the open Malaysian economy that thrives on free and fair trade. The plaintiffs' claim was therefore dismissed with costs of RM50,000.00 as agreed costs.

Grounds Of Appeal

[23] The plaintiffs are not happy with the decision. They raised various grounds in the memorandum of appeal to say that the learned judge had erred in law and/or in fact in dismissing the 1st plaintiff's claim with costs for trade mark infringement as follows:

Trade Mark Infringement

1. Failing to find that the "Skyworld" and "Sky World" words or marks used by the 1st to 4th respondents (hereinafter referred to as "Corporate Respondents") as part of their corporate names, property development project name "Sky World City Sabah" (hereinafter referred to as "Project Name") and domain name "Skyworldcity.net" (hereinafter referred to as "Domain Name") have infringed upon the following trade mark registration duly obtained by the 1st appellant:

SkyWorld

a. "design the experience" trade mark registered under Registration No: 2014008384 in Class 37; and

SkyWorld

b. "design the experience" trade mark registered under Registration No: 2014010514 in Class 37.

(the abovementioned marks referred to in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b) are hereinafter collectively referred to as "1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks").

3. Failing to apply the proper test for trade mark infringement as laid down in Low Chi Yong v. Low Chi Hong & Anor [2017] 6 MLRA 412 and many other case law in determining whether there is an infringement of the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks by the Respondents.

4. Failing to take into account the essential feature and/or striking feature and/or substantial portion of the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks, namely, "SkyWorld" in determining whether there is a likelihood of confusion between the Corporate Respondents' corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name which incorporated the said work/mark "Sky World" and the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks.

5. Finding that the "dominant mark" used by the appellants is only "Sky" with a wavy device beneath.

6. Failing to apply the proper test in arriving at the decision that the services provided by and/or intended to be provided by the Corporate Respondents are different from the services in respect of the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks, namely "real estate development; property development; housing development; building project development; building and construction of real property" in Class 37, among others.

7. Holding that the Corporate Respondents' corporate name and domain name used in connection with the Corporate Respondents' Project Name is unlikely to deceive and cause confusion when only a likelihood of confusion is to be considered.

8. Failing to critically consider all and every relevant evidence and to properly evaluate and appreciate the evidence when His Lordship ruled that there is no likelihood of confusion as follows:

a. the learned judge failed to take into account all relevant consideration including but not limited to the doctrines or principles of imperfect recollection and essential feature when His Lordship decided that there is no likelihood of confusion between the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks and the Corporate Respondents' corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name incorporating the word/mark "Skyworld";

b. the learned Judge erred in holding that the degree of similarity between the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Mark and the Corporate Respondents' corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name incorporating the word/mark "Skyworld" is insufficient to cause deception or confusion;

c. the learned judge had misdirected himself when His Lordship accepted and applied the Bruneian High Court case of Ayamas Convenience Stores Sdn Bhd v. Ayamas Sdn Bhd [1994] 3 MLRH 222 in deciding that there is no likelihood of confusion;

d. the learned judge erred in law and/or in fact in totally disregarding the evidence of actual confusion on the part of the members of the public as demonstrated by two e-mails which emanated from two members of the public addressed to the appellants enquiring whether the appellants and the Corporate Respondents are related (hereinafter referred to as "said e-mails"); and

e. the learned Judge erred in law and/or in fact in failing to critically and properly appreciate all documentary evidence, especially contemporaneous documentary evidence in the form of the said e-mails.

9. Failing to fully recognise and enforce the exclusive rights granted to the 1st appellant's by the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks pursuant to s 35 of the Trade Marks Act 1976 (hereinafter referred to as "Act").

Passing off

10. Finding that the Appellants had a "short corporate history" and thus failed to establish the requisite goodwill for proving the tort of passing off when in fact the 1st appellant had first used the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks and the following trade marks when it launched its first project, Ascenda Residence, as early as in 2014:

SkyWorld

a. "design the experience"; and

b. the word or marks, "SkyWorld".

(the above-mentioned marks referred to in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b) above are hereinafter collectively referred to as "Appellants' Common Law SkyWorld Trade Marks").

11. Failing to critically examine and appreciate all the evidence adduced by the appellants that the word/mark "SkyWorld" has through extensive use by the appellants acquired the requisite goodwill and reputation and is distinctive of the appellants and no others, and as such the said word/mark "SkyWorld" has in fact and in law became the badge of origin of the appellants' services.

12. Holding that the appellants' goodwill or reputation was not "sufficiently well-known" for them to sustain an action for passing off, despite having found that the appellants had established goodwill in the appellants' Common Law SkyWorld Trade Marks.

13. Failing to properly appreciate that the test on the facts which constitute the elements of likelihood of confusion in respect of an action for trade mark infringement are different from the test of proving misrepresentation in an action for passing off. In particular, the learned Judge erred in law and/or in fact when His Lordship only compared the 1st appellant's Registered Marks, instead of the appellants' badge of origin, namely, the word/mark "SkyWorld", with the Corporate Respondents' corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name in deciding whether there has been any misrepresentation on the part of the Corporate Respondents.

14. Finding that there had not been any misrepresentation by the Corporate Respondents on the ground that the services are different without taking into account that the services are very closely related or allied.

15. Failed to appreciate that the Corporate Respondents, being the subsequent users of the word/marks "SkyWorld", bear the burden to prove that their choice of the word "SkyWorld" as the prominent part of their corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name were made in good faith and such use will not lead to misrepresentation.

16. Holding that the appellants did not suffer any damage in the absence of proof of misrepresentation. Further, the learned Judge erred in law and/or in fact in failing to appreciate that the appellants are likely to suffer damage due to the Corporate Respondents having passed off their business as that of as associated with the appellants despite:

a. the misappropriation of the appellants' goodwill and reputation by the Corporate Respondents;

b. the appellants' loss of exclusivity to the 1st appellant's Registered Trade Marks and the appellants' Common Law SkyWorld Trade Marks; and

c. mistaken association between the respondents' negative reputation as and for the appellants' substantial and prestigious reputation and goodwill.

Unlawful Interference

17. Finding that the respondents had not unlawfully interfered with the 1st appellant's business when in fact the Corporate Respondents' infringing activities and acts of passing off constituted such unlawful means which in fact interfered with the appellants' legitimate businesses.

Other Grounds

18. The learned Judge erred in law and/or in fact in failing to find that the respondents' witnesses/ DW1 and DW2, were not credible witnesses, particularly, in relation to the creation and choice of the Corporate Respondents' corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name at trial.

19. The learned Judge erred in law and/or in fact in holding that the adoption and usage of the word/mark "Sky World" and/ or "Skyworld" as the Corporate Respondents' corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name were coincidental even though the respondents failed to offer any explanation on the alleged creation or choice of the Corporate Respondents' corporate names, Project Name and Domain Name used by the Corporate Respondents.

20. The learned judge erred in law and/or in fact in failing to pierce the Corporate Respondents' corporate veil and failing to rule that the 5th and 6th respondents, being the alter ego and directing minds and will of the Corporate Respondents, were liable for the Corporate Respondents' act of trade mark infringement, passing off and unlawful interference with trade.

21. The learned Judge erred in law and in concluding that there should be free trade in the Malaysian economy when His Lordship completely ignored or failed to acknowledge an enforce the statutory rights granted to the 1st appellant as the registered proprietor of the duly registered trade marks pursuant to the Trade Marks Act 1976 and the appellants' common law rights over the word/mark "SkyWorld".

[24] In gist, there is non-consideration or insufficient judicial appreciation of material evidence by the trial judge and that the findings do not accord well with the probabilities of the case. The learned judge had also misapprehended and applied the wrong principles of law in determining the issue of infringement of trade mark, passing off and unlawful interference with trade.

The Appeal

[25] Our task is to determine whether the learned judge's finding warrants an appellate intervention (see: Gan Yook Chin & Anor v. Lee Ing Chin & Ors [2004] 2 MLRA 1 and F&N Dairies (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd v. Tropicana Products Inc & Other Appeals [2013] 6 MLRA 558).

[26] The parties had filed their written submissions and we also heard their oral submissions. In this case, we noted that the infringement of plaintiffs' Trade Marks is not caused by a direct use of the said trade marks by the defendants in their products or business but instead the offending marks are part of the defendants' corporate names. Hence, the issue in our view is whether the Corporate Defendants' name which resembles the plaintiffs' Trade Marks can be held liable for trade mark infringement in respect of the use of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks as part of their company name.

[27] As parties' submissions did not fully address the issue which we thought is very relevant to the facts of this case before us, we allowed parties to file in further submissions on the specific issue that we had raised. Upon sending us the further submissions, we will study the submissions and also take into considerations of the main submissions and deliver our decision on a date to be fixed.

[28] Parties had filed in their further submissions. Firstly, it was established that the Corporate Defendants have used "Skyworld" and "Sky World" as a trade marks in the course of their trade. Secondly, whether such action is allowable under the trade mark law. If the answer is in the positive, then our view is, there is clear infringement on the plaintiffs' trade mark and consequently on the issue of passing off and unlawful interference of trade, if otherwise the judgment of the High Court may not be intended to be disturbed.

The Issue

Whether The Corporate Defendants' Name Which Resembles The Plaintiffs' Trade Marks Can Be Held Liable For Trade Mark Infringement In Respect Of The Use Of The Skyworld Registered Trade Marks As Part Of Their Company Names?

Trade Mark Infringement

[29] The law on infringement of trade marks is quite settled. The burden of proof in a trade mark infringement case lies on the plaintiffs. The current legal position is as set out in the Federal Court case of Low Chi Yong v. Low Chi Hong & Anor [2017] 6 MLRA 412 which the learned judge had cited. We agreed with him. In fact, s 38 of the TMA provision is clear on Infringement of a Trade Mark as follows:

Section 38(1)

"A registered trade mark is infringed by a person who, not being the registered proprietor of the trade mark or registered user of the trade mark using by way of permitted use, uses a mark which is identical with it or so nearly resembling it as is likely to deceive or cause confusion in the course of trade in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered in such a manner as to render the use of the mark likely to be taken either:

(a) as being use as a trade mark;

(b) in a case in which the use is use upon the goods or in physical relation thereto or in an advertising circular, or other advertisement, issued to the public, as importing a reference to a person having the right either as registered proprietor or as registered user to use the trade mark or to goods with which the person is connected in the course of trade; or

(c) In a case in which the use is use at or near the place where the services are available or performed or in an dvertising circular or other advertisement issued to the public, as importing a reference to a person having a right either as registered proprietor or as registered user to use the trade mark or to services with the provision of which the person is connected in the course of trade."

[30] As to the meaning to be ascribed to the word "use" found in s 38 TMA, s 3(2) TMA provides as follows:

"In this Act:

(a) references to the use of a mark shall be construed as references to the use of a printed or other visual representation of the mark;

(b) references to the use of a mark in relation to goods shall be construed as references to the use thereof upon, or in physical or other relation to, goods; and

(c) references to the use of a mark in relation to services shall be construed as references to the use thereof as a statement or as part of a statement about the availability or performance of services."

[31] In the case of Al-Baik Fast Food Distribution Co Sae v. El Baik Food Systems Co Sa [2016] 4 MLRH 361, the learned High Court Judge (as he was then) stated as follows:

"Under s 3 of the TMA, the use of a mark in relation to goods shall be construed as 'references to the use thereof upon, or in physical or other relation to goods'. Therefore, as our law mandates that the trade mark be used upon' the goods, then there must be actual use of the marks on goods in Malaysia."

[32] The defendants took a stand that under s 38 of the TMA, the use of a company names or trade name is not in itself usage "in relation to goods or services" for the following reasons:

(i) Section 38 TMA read with s 3(2) would mean that in order to constitute infringement, there must not only be usage of an identical or similar mark, but such usage must also be upon or in relation to goods marketed or services provided by the alleged infringer.

(ii) It is clear from the scheme of s 38 TMA (as well as the TMA as a whole) that the intended purpose of the said Section is to protect the public from being deceived or confused as to the source of goods or services, or to put it another way, to enable the public to distinguish goods or services of one party from that of the good or services of another party ie the registered proprietor of a trade mark.

[33] The defendants submitted that the plaintiffs' claim ought to be dismissed given that the Corporate Defendants' company names have been registered with the Registrar of Companies ("ROC") and is therefore a valid name. The purpose of a company name or trade name is not, of itself, to distinguish goods or services, but instead is to identify a company or business being carried on.

[34] In support, the defendants referred to the European Court's judgments which had recognised the purpose of a company name or trade name is not to distinguish goods or services:

Robelco v. Robeco Groep [2002] EUECJ C-23/01 (Approximation of law):

"34. Accordingly, where, as in the main proceedings, the sign is not used for the purposes of distinguishing goods or services, it is necessary to refer to the legal orders of the Member States to determine the extent and nature, if any of the protection afforded to owners of trade marks who claim to be suffering damage as a result of use of that sign as a trade name or company name.

35. The Member States may adopt no legislation in this area or they may, subject to such conditions as they may determine, require that the sign and the trade mark be either identical or similar, or that there be some other connection between them."

Anheuser-Busch v. Budejovicky Budvar, narodni podnik [2004] EUECJ C-245/02 (External relations):

"However, where the examinations to be carried out by the national court, referred to in para 60 of this judgment, show that the sign in question in the main case is used for purposes other than to distinguish the goods concerned - for example, as a trade or company name - reference must, pursuant to art 5(5) of Directive 891104, be made to the legal order of the Member State concerned to determine the extent and nature, if any, of the protection afforded to the trade mark proprietor who claims to be suffering damage as a result of use of that sign as a trade name or company name (see Case C-'23101 Robe/co [2002] ECR 1-'10913, paras 31 and 34)."

[35] The defendants submitted that merely using a mark as a company name or trade name cannot in itself be construed as being usage 'in relation to goods or services' within the meaning of s 38 TMA so as to constitute infringement. It was further submitted that if the usage of an identical or similar company or trade name is to constitute infringement at all, then with respect our TMA must be amended such as was done to s 10 of the UK Trade Marks Act 1994 which now specifically states that using a sign (mark) includes using the sign as a trade or company name or part of a trade or company name.

[36] It is the defendants' stand that the mere act of having or using a company name or trading name which is identical or similar to another entity's registered trade mark (or any part thereof) is not in itself an act of infringement of the registered trade mark. In other words, it is perfectly possible for one entity to have a company/trade name which is identical or similar with another entity's registered trade mark without the former entity infringing the latter's registered trade mark.

[37] On the other hand, the plaintiffs submitted that such argument is unsustainable for the following reasons:

(i) the Corporate Defendants' registration of 1st plaintiff's trade mark as their company name does not operate as a defence as the statutory defences in respect of a claim for trade mark infringement are expressly provided in s 40(1) of the TMA, which does not include the use of the mark as a company name.

(ii) the registration of the Infringing Names as company names clearly violates the prohibitions under ss 25(2) and 26 of the 2016 Act as the Corporate Defendants' name is practically identical to the plaintiffs' name (save for the generic words "Holdings", "Sabah", "Sdn" and "Bhd"). Sections 25(2) and 26 of the 2016 Act provide that:

"25. (2) A company may have as its name:

(a) an available name; or

(b) any such expression as the Registrar may assign upon its incorporation.

26 (1) A name is available if it is not:

(a) undesirable or unacceptable;

(b) identical to an existing company, corporation or business;

(c) identical to a name that is being reserved under this Act; or

(d) a name of a kind that the Minister has directed the Registrar not to accept for registration.

(2) The Registrar shall have the power to determine whether a name referred to in paragraph (1)(a), (b) or (c) is undesirable, unacceptable or identical, as the case may be.

(3) The Registrar shall publish in the Gazette any direction referred to in paragraph (1)(d)."

(iii) In determining whether a name is undesirable or unacceptable, the ROC is guided by the Guidelines on Company Names ('Guidelines'), which provide that:

"The Registrar has a full discretion in determining whether a name is undesirable or unacceptable. In exercising that discretion, the Registrar may determine that a name is undesirable or unacceptable if:

(a) contains words of an obscene nature;

(b) it is contrary to public policy including names which are set out in paras 3;

(c) it may likely offend any particular section of a community or any particular religion; or

(d) Names that are misleading as to the identity, nature, objects or purposes of a company or in any other manner."

(iv) The Guidelines further provide that in ascertaining whether the Corporate Defendants' company names are identical to the plaintiffs' company names, the following components shall be disregarded:

"(a) "The": where it is the first word of the name;

(b) "Sendirian", "Sdn", "Berhad" and "Bhd";

(c) the following words and expressions where they appear at the end of the name: "company", "and company", "corporation", "Incorporated", "Holding", "Group" "Malaysia";

(d) any word or expression which in the opinion of the Registrar, is intended to represent any word or expression in sub-paragraph (c);

(e) the plural version of the name;

(f) the type and case of letters, spacing between letters and punctuation marks; and

(g) the symbol is deemed to have the same meaning as the word "and".

[Emphasis Ours]

[https://www.ssm.com.my/Pages/LegalFramework/PDF%20Tab%202/ guidelines on names.pdf) at paras [12]-[13]

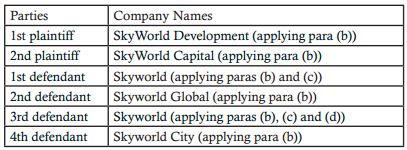

[38] Applying the Guidelines set out in paragraphs above, the plaintiffs submitted that the plaintiffs' and Corporate Defendants' names are practically identical as follows:

[39] The ROC is empowered under s 29 of the Companies Act 2016 "to direct a company to change its name if he believes on reasonable ground that a name under which the company was registered should not have been registered". Therefore, the registration of the company's name does not mean it is immune from being changed in appropriate circumstances.

[40] By reason of the aforesaid, the plaintiffs' stand is that the registration of the Infringing Names by the ROC cannot be taken to mean that the said names are valid under trade mark law. The legality of the Corporate Defendants' use of the Infringing Names should not be viewed in isolation from the TMA. Otherwise, an infringer or tortfeasor would be able to circumvent the protection conferred to a registered trade mark under the TMA by registering and using the said mark as a company name. The registration and use of the trade mark as a company name by the tortfeasor is a "back-door" entry to circumvent the registration of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks.

[41] The plaintiffs referred to the Bombay High Court's decision of Poddar Tyres Ltd v. Bedrock Sales Corporation Ltd [1993] AIR Bom 237 (at para [45]) which says as follows:

"It is open to the plaintiffs to move under the provisions of the Companies Act for cancelling the name of the 1st defendants, if so advised, but that, by itself. Do[e]s not preclude the plaintiffs from bringing an action for infringement of their registered trade mark and/or passing off?"

[42] Based on the submission, the plaintiffs' counsel urged this Court to injunct the Corporate Defendants from using the SkyWorld Names and Marks as part of their company names, domain name and project name. We were invited to adopt the English High Court's approach in Panhard v. Panhard [1901] 18 RPC 405 wherein the learned judge, Farwell J, ordered the defendant to change its company name having found that its name is colourably similar to the plaintiff's name. We sensed that this is the concession the plaintiffs' counsel was willing to accept in any event.

Our Decision

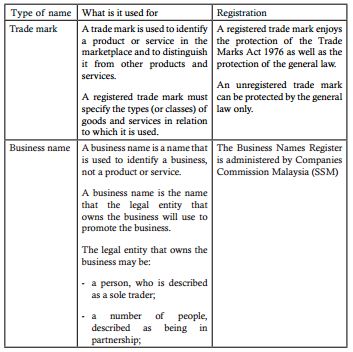

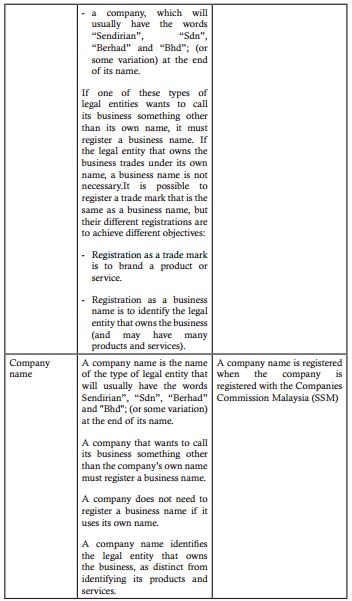

[43] To begin with, what are the difference between trade marks, business names, company names and domain names? The table below will show the differences:

[44] As alluded to earlier, the defendants' counsel had argued that once the Corporate Defendants' company names have been registered with the Registrar of Companies ("ROC") it is a valid name and the purpose of a company name or trade name is not, of itself, to distinguish goods or services, but instead is to identify a company or business being carried on. The intended purpose of the scheme of s 38 TMA (as well as the TMA as a whole) is to protect the public from being deceived or confused as to the source of goods or services, or to put it another way, to enable the public to distinguish goods or services of one party from that of the good or services of another party ie the registered proprietor of a trade mark. In other words, s 38 of TMA does not apply to the Corporate Defendants.

[45] In Malaysia, under s 22 of the Companies Act 1965 (1965 Act), the process of incorporation commences with the applicant applying in the prescribed form (Form 13A) to the Registrar of Companies for a search on the availability of the name for the intended company. The Registrar of Companies shall reserve the proposed name for a period of three months from the date of lodging the application if he is satisfied as to the bona tides of the application and the proposed name is not undesirable or is a name or a name of a kind that the Minister has directed the Registrar of Companies not to accept for registration.

[46] In contrast, the Companies Act 2016 (2016 Act) merely requires a person to apply to the Registrar of Companies to confirm the availability of the proposed company name. The Registrar of Companies may reserve the name for a period of 30 days (instead of three months under the 1965 Act) from the date of lodgment of the application together with the prescribed fee if he is satisfied that the proposed name is not undesirable or is a name or a name of kind that the Minister has directed the Registrar of Companies not to accept for registration.

[47] In comparison with s 22 of the 1965 Act, the 2016 Act has clarified the criteria for the Registrar of Companies to approve a company's name. Section 26(1) of 2016 Act provides that the name can be approved if it is not:

(a) undesirable or unacceptable;

(b) identical to an existing company, corporation or business;

(c) identical to a name that is being reserved under the 2016 Act; or

(d) a name that the Minister has directed the Registrar of Companies not to accept for registration.

[48] Where the Registrar of Companies determines that a name is undesirable, unacceptable or identical to an existing company, corporation or business or a name that is being reserved, he shall then publish in the Gazette any direction to that effect.

[49] The Corporate Defendants were all incorporated in 2017. The names had been accepted and registered by the ROC. The fact that the names had been accepted and registered, in our view, the Corporate Defendants' names are valid as the names are not being undesirable or unacceptable under para (a) and not identical to an existing company, corporation or business under para (b) of s 26(1) of the 2016 Act.

[50] The 1st plaintiff changed its name to SkyWorld Development Sdn Bhd on 5 December 2014 for the group to use a name which can also be used as their house mark for all their development projects. The "SkyWorld" mark was first used in 2014 for the plaintiffs' Ascenda Residence @ SkyArena Setapak project ("SkyArena project"). The mark "SkyWorld" (without taglines) is used in the plaintiffs' write-ups, press releases as well as in their sales galleries.

[51] It was an issue for the plaintiffs as to how the Corporate Defendants' names were approved in 2017 when the plaintiffs' names had been accepted, approved and registered earlier in 2014. It cannot be disputed that at the time the Corporate Defendants were incorporated, the plaintiffs are already in existence or incorporated. They claim that the registration of the Infringing Names as company names clearly violates the prohibitions under ss 25(2) and 26 of the 2016 Act as the Corporate Defendants' names are practically identical to the plaintiffs' names (save for the generic words "Holdings", "Sabah", "Sdn" and "Bhd")?

[52] Section 26(2) of the 2016 Act only provides that the Registrar shall have the power to determine whether a name referred to in s 26(1)(a), (b) or (c) is undesirable, unacceptable or identical, as the case may be. In our view, the Corporate Defendants' name are not identical with the plaintiffs' name except the word "Skyworld" were used. Our further view is that the Registrar's power under s 26(2) of 2016 Act does not extend to refusal of any application for registration if the names may offend any existing trade marks registered under the TMA. Moreover, the plaintiffs' companies' names and their company registration/identity numbers (s 15 of 2016 Act) are different from the Corporate Defendants' registration/identity number although the words "Skyworld" are used as parts of the names.

[53] Based on all the company names which had been approved and registered by the ROC, it is our considered view that the registration of the names using the word "Skyworld" or "SkyWorld" per se did not contravene s 26(2) of the 2016 Act if it is not identical with the existing company. The learned judge held that the adoption and hence usage of "Skyworld" by the parties for purposes of their corporate names as well as project name was in fact coincidental. The defendants did not purposely adopt the same to imitate or interfere with the plaintiffs' business and what more; by way of unlawful means. Finally, it is the learned judge's decision that in this case there should be concurrent use of trade name in the open Malaysian economy that thrives on free and fair trade.

[54] We may agree with the learned judge's opinion that the Corporate Defendants should be given the benefit of the doubt to the concurrent use of the trade name in the open Malaysian economy. However, in our view it remains an issue whether the Corporate Defendants had interfered with the plaintiffs' real estate business in respect of the usage of the names as trade marks.

[55] There are other companies that have used the word "SkyWorld". In any event, the fact that the plaintiffs have not pursued action against the other companies/parties using the word "SkyWorld" does not preclude them from pursuing this claim against the defendants. This was explained by the High Court in Intel Corporation v. Intelcard Systems Sdn Bhd & Ors [2003] 3 MLRH 668, where it was held that:

"54. From the defendant's submission, it can only be derived that it is based on a simplistic view that there are hundreds of other companies using the 'Intel' name without permission; why pick on the defendant? I cannot help but disagree with such a suggestion. Just as absurd is the defendant's suggestion that the plaintiff's action against the defendant is untenable because it has not succeeded in taking action against hundreds of companies with the 'Intel' prefix as mentioned by the defendant."

[56] The purpose of registering a business name is to ensure that consumers and businesses that one deals with are able to identify or ascertain who the operator or actual legal owner of the business is. However, registered trade marks enjoy the protection of the TMA as well as the protection of the general law.

[57] In relation to registration of a business name, company name or a website domain we come across an Australian Article by MurfettLegal Professionalism. Understanding. Result. (www.murfett.com.au), which states that:

"It is a (very) common misconception that the registration of a business name (under the Business Name Registration Act 2011 (Cth)), company name (with ASIC) or a website domain name confer some form of ownership or exclusive rights to the use of that name in Australia. It doesn't! Only if the name is registered as a trade mark does it confer such rights. Having a registered trade mark can provide legal protection for your business, its brand(s) and goodwill and gives you statutory rights to prevent another business from using the same or similar trade mark. A registered trade mark can also be most valuable marketing tool, as well as quite often an appreciating asset on you balance sheet. Choosing a business name that infringes (inadvertently or otherwise) an existing trade mark can be a costly exercise. It could mean drawn out disputes, legal costs and possibly being compelled to cease using business name. The purpose of registering a business name is to ensure that consumers and businesses that you deal with are able to identify or ascertain who the operator or actual legal owner of the business is. Registration also ensures that every business complies with the Business Name Registration Act 2011 (Cth). Registration is mandatory (with some exceptions) and it must be done before the business starts trading. Businesses who fail to register their business name can be fined."

[58] The Articles also suggests things to note when registering a business name as follows:

- always check whether your business name may infringe a registered trade mark by conducting a trade mark search using IP Australia's website (http://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/).

- If your registered business name infringes a registered trade mark, the trade mark owner may apply to the courts to cancel your business name.

- If the trade mark owner is successful, it will mean you have to trade under a new business name, change your marketing and advertising materials and signage, and lose the branding and the goodwill that you have built up under the old business name.

[59] Further, a domain name is unique website address (or more specifically the Universal Reference Locator (URL) on the internet (eg www.murfett.com. au), it is the online identity for your business. Modern technology and the increasing reliance on the internet means that domain names are important marketing tools to generate traffic for businesses. Although a third party cannot register a domain name that you have already registered, this again does not mean that you have the exclusive right to use the domain name. Similar to a business name, if your registered domain name infringes a registered trade mark, the trade mark owner may (issue a 'cease and desist' letter, demanding that you cease using the domain name. The trade mark owner can also commence proceedings against you for 'passing off' their registered trade mark. A trade mark is a right that is granted over a word, phrase, letter, number, sound, smell, shape, logo, picture or packaging your business uses to represent its goods and services. It is used to distinguish your goods or services from your competitors. A registered trade mark under the Trade Marks Act 1995 gives the exclusive legal right to use, license and sell your intellectual asset in Australia (MurfettLegal 2017).

[60] The Corporate Defendants are all involved in businesses relating to real estate activities, project development and/or retail sale of construction materials. The defendants are presently embarking on its maiden Sky World City project in Karambunai, Sabah, East Malaysia. Whereas, the 1st plaintiff is the registered proprietor of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks in Class 37 in respect of inter alia "real estate development"; "property development"; "building project management"; and "building and construction of real property". The SkyWorld name forms part of the plaintiffs' company names.

[61] The plaintiffs contended that members of the public would identify the plaintiffs' project as "SkyWorld's project" (without the tagline) and not "SkyWorld design the experience project" (with the tagline). The learned judge considered the defendants' project is residential accommodation buildings planned to be built in the Sky World City project. In other words, there are similarities in the defendants' business or project and the plaintiffs' business or project.

[62] As pointed out, the requisite elements for establishing trade mark infringement pursuant to s 38 of the TMA had been clearly stated in the Federal Court case of Low Chi Yong v. Low Chi Hong & Anor [2017] 6 MLRA 412. In other words, trade mark infringement is an unauthorised use of a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, a registered trade mark, is an infringement. A trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles the other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion. Occasionally, a 'well-known' registered mark can be infringed by the use of a similar mark on dissimilar goods or services, as the mark could indicate an apparent connection between the unrelated goods or services and the registered owner of the trade mark. This adversely affects the interests of the registered owner. For example, using 'Coca-Cola' as a trade mark in relation to sweets could infringe the legitimate 'Coca-Cola' trade mark even if it was only registered in relation to beverages.

[63] The learned judge agreed that the principal similarity is in the defendants' corporate names and domain name and the plaintiffs' Registered Trade Marks arising from the word "Skyworld". He had also agreed that the 1st plaintiff's trade mark is a stylish verbal mark visually comprising the word SkyWorld save that with the letters "S" and "W" spelt in uppercase letter with a stroke underneath the word "Sky" together with the phrase "design the experience". The other one of them has the same characteristics but with additional four Chinese characters underneath the phrase "design the experience". The learned judge found that there is no resemblance between them whatsoever. Eventually, he held that there is no infringement of 1st plaintiff's trade marks.

[64] However, we were of the view that the learned judge had erred in law as it is trite that a plaintiff in an infringement action is not required to establish that the infringing mark is identical. It would suffice for the plaintiff to establish that the infringing mark so nearly resembles the registered trade mark as is likely to deceive or cause confusion (Tohtonku Sdn Bhd v. Superace (M) Sdn Bhd [1992] 1 MLRA 350). For the purpose of ascertaining whether there is a likelihood of confusion between two competing marks, other features (if any) outside the actual trade mark used by the defendants should not be taken into account (Saville Perfumery Ltd v. June Perfect Ltd [1941] 58 RPC 147, CA at 161). We agreed with the plaintiffs that the learned judge should not be drawn into conducting a microscopic comparison of the minute differences between the Competing Marks, namely, whether the Corporate Defendants' marks/words are used in uppercase or lowercase (Hu Kim Ai & Anor v. Liew Yew Thoong [2005] 4 MLRH 718).

[65] By the given facts, we were of the view that the 1st plaintiffs had established paras (a), (b) and (c) of s 38(1) TMA. We were also of the view that the use of the Infringing Names by the Corporate Defendants is likely to cause confusion or deception as the Infringing Names are aurally and visually similar to the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks. The Corporate Defendants have used the Infringing Names as trade marks in the course of their trade as defined under s 3(1) and (2) of the TMA.

[66] It is not disputed that the Infringing Names incorporate the essential feature of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks, namely "SkyWorld". It is also not disputed that the Corporate Defendants are neither the registered proprietors nor the registered users of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks. We found that the learned judge had erred in not enquiring whether the use of the Infringing Names and Marks comes within the specification of services covered by the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks, inter alia, "real estate development"; "property development"; "building project management"; and "building and construction of real property". Instead, the learned judge was embarking on a wrong enquiry of whether the plaintiffs and the defendants were engaged in the same business in determining the issue of trade mark infringement.

[67] We agreed with the plaintiffs' submission that when the court is examining the specifications of the plaintiffs' registration in ascertaining whether the defendants' activities come within the scope of that specification, the court must have regard to the following principles:

(i) the words or phrases found in the specification of goods or services of a trade mark registration should be given their ordinary and natural meanings and should be confined to the core or substance of possible meanings (Avnet Inc v. Isoact Ltd [1998] FSR 16 at 19);

(ii) the words in the specification should be given their natural meaning within the context in which they are used. They cannot be given an unnaturally narrow meaning (Beautimatic Inernational Ltd v. Mitchell International Pharmaceutical Ltd and Another [2000] FSR 267 at p 275); and

(iii) the trade mark registration should not be allowed such a liberal interpretation that their limits become fuzzy and imprecise. Where words or phrases in their ordinary and natural meaning are apt to cover the category of goods or services in question, there is equally no justification for straining the language unnaturally, so as to produce a narrow meaning which does not cover the goods or services in question (YouView TV Ltd v. Total Ltd [2012] EWHC 3158 (Ch) at [12]).

[68] It was submitted that taking the natural and ordinary meanings of the words found in the relevant specification of services of the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks, ie "real estate development", "property development and "building and construction of real property", these words would include the Corporate Defendants' business of constructing and developing a theme park. It is undeniably true the Corporate Defendants' business activities involve property development and/or construction of real property.

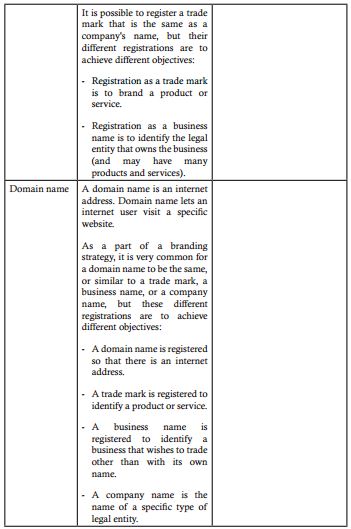

[69] The specification of services as registered under the SkyWorld Registered Trade Marks in Class 37, and the Corporate Defendants' services or business as culled from the evidence adduced are as follows:

The 1st defendant further identifies itself as "Sky World" in its presentation to its investors regarding the purported Sky World City Sabah project as shown below:

The Corporate Defendants' alleged tourism project is known as "Sky World City Sabah" is as shown below:

[70] We agreed with the plaintiffs' submission in ascertaining the likelihood of confusion, proof of actual confusion is not necessary (Ho Tack Sien & Ors v. Rotta Research Laboratorium Spa & Anor And Another Appeal; Registrar Of Trade Marks (Intervener) [2015] 3 MLRA 611 (para [29]). Notwithstanding, it would be beneficial for the plaintiffs if they are able to adduce evidence of actual confusion (Yong Sze Fun & Anor v. Syarikat Zamani Hj Tamin Sdn Bhd & Anor [2012] 2 MLRA 404 (para [237])).

[71] The plaintiffs had also adduced evidence of actual confusion vide two e-mails from the public enquiring whether the plaintiffs and the Corporate Defendants are related (see pp 1092-1095 Rekod Rayuan (Jilid 2C). The plaintiffs answered to the queries from Venugopal and John Smith that the plaintiffs' companies are not related and not connected in any form or manner howsoever with the Corporate Defendants. The plaintiffs had also adduced a certificate pursuant to s 90A(2) of the Evidence Act 1950 by SP1 (see p 1089), which dispenses the need to call the maker of these e-mails. In our opinion, a certificate under s 90A(2) is not the only method to prove a document was produced by a computer. The witness may give oral evidence to the same effect. Section 90A(4) of the Evidence Act 1950 states:

"(4) Where a certificate is given under subsection (2), it shall be presumed that the computer referred to in the certificate was in good working order and was operating properly in all respects throughout the material part of the period during which the document was produced."

[72] The authority on this point is found in the case of Ahmad Najib Aris v. PP [2009] 1 MLRA 58 (Federal Court):

"A certificate under s 90A(2) of the Evidence Act 1950 is not the only method to prove that a document was produced by a computer 'in the course of its ordinary use' under s 90A(1) of the Evidence Act 1950. Section 90A(6) deals with the admissibility of a document which was not produced by a computer in the course of its ordinary use and is only deemed to be so. The fact that a document was produced by a computer in the course of its ordinary use may be proved by the tendering in evidence of a certificate under s 90A(2) or by way of oral evidence. Such oral evidence must consist not only of a statement that the document was produced by a computer in the course of its ordinary use but also of the matters presumed under s 90A(4)."

[73] The fact can also be established by oral evidence. We absolutely agree with the above case of Ahmad Najib Arts v. PP (see also Gnanasegaran Pararajasingam v. Public Prosecutor [1995] 2 MLRA 555, Standard Chartered Bank v. Mukah Singh [1996] 4 MLRH 438 (HC) and Evidence Practice and Procedure Second Edition by Augustine Paul at p 640). In light of the evidence and the authorities above, the requirements of s 90A(4) of the Evidence Act 1950 has been complied with. The learned judge erred by disregarding the e-mails and attaching no weight to them despite the e-mails having been produced by the parties. The learned judge ought to critically examine the truth of their contents against the probabilities of the case and all of the evidence adduced before him.

[74] Based on the evidence shown, we agreed that the plaintiffs had established all the elements constituting trade mark infringement under s 38 of the TMA. We had no hesitation to find the Corporate Defendants to be held liable for trade mark infringement in respect of their use of the Infringing Names in the company names, domain name and project name.

[75] The courts in Malaysia and other common law jurisdictions have also decided that the use of a registered trade mark as a company name would amount to trade mark infringement in the following cases:

Malaysian position:

Mutiara Rini Sdn Bhd v. The Corum View Hotel Sdn Bhd [2015] MLRHU 1013:

The court allowed the plaintiff's application for summary judgment against the defendant for trade mark infringement and passing off in respect of the defendant's use of the plaintiff's registered mark, "The Curve" in the defendant's company name "The Curve Hotel Sdn Bhd". The learned judge applied the requirements under s 38 of the TMA and decided that:

"[17] Thus, the facts clearly show that the defendant has used the said trade mark 'The Curve' without the consent of the plaintiff. The defendant has used the mark as part of the business name of the defendant and the same was used in the course of the hotel business of the defendant. Therefore, all the elements of infringement have been satisfied."

Syarikat Wing Heong Meat Product Sdn Bhd v. Wing Heong Food Industries & Ors [2009] 1 MLRH 947:

The Federal Court held that the plaintiff's use of the defendant's registered mark "Wing Heong" as part of the plaintiff's company name amounted to trade mark infringement.

[76] There is a plethora of cases which held that the unauthorised use of a plaintiff's trade mark as part of the defendant's corporate name or trading style would amount to passing off. The relevant cases in a chronological order are as follows:

(a) Revertex Ltd & Anor v. Slim Rivertex Sdn Bhd & Ors [1989] 3 MLRH 359 (citing Excelsior Pte Ltd v. Excelsior Sport (S) Pte Ltd [1985] 2 MLRH 434);

(b) Dun & Bradstreet (Singapore) Pte Ltd & Anor v. Dun & Bradstreet (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd [1993] 1 MLRH 211.

(c) Compagnie Generale Des Eaux v. Compagnie Generale Des Eaux Sdn Bhd [1996] 1 MLRH 282; and

(d) Trinity Group Sdn Bhd v. Trinity Corporation Berhad [2012] MLRHU 309

Singaporean position:

Clinique Laboratories, LLC v. Clinique Suisse Pte Ltd and Another [2010] 4 SLR 510

The court held the defendants liable for trade mark infringement in respect of their use of the registered mark "CLINIQUE" in inter alia:

(i) the 1st defendant's company name "Clinique Suisse Pte Ltd"; (ii) the trading name "CLINIQUE SUISEE"; and (iii) the domain name www.cliniquesuisse.com.

Australian position:

(a) Insight Radiology Pty Ltd v. Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2016] 122 IPR 232:

The Australian Federal Court decided that Insight Radiology Pty

Ltd's ("IR") use of the registered composite mark"

" as part of inter alia its corporate name amounted to trade mark infringement.

(b) Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v. Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] 118 IPR 239:

The Australian Federal Court decided that the defendant was liable for infringing the registered mark "Flexopack" in respect of its use of the said mark as its company name. Further, the court in the passages below, went on to hold that the respondent ought to have been more careful in choosing its company name to avoid infringing the trade mark rights of others:

"[14] Generally, I found the 1st respondent's director's evidence to be unreliable. I am not prepared to accept that [the 1st respondent's director] did not know of the applicant at the time the 1st respondent adopted its company name and of the potentiality for confusion.

...

A person seeking to identify whether a name is available for use could have quickly and simply conducted a Google search. I have significant doubts as to the veracity of [the 1st respondent's director] denial on this aspect that he did not carry out such a search. It was not disputed, as I understood it, that a general Google search would have thrown up the applicant.

...

[145] Further, the 1st respondent's director did not make any enquiries of cheese manufacturers before choosing his company name. Further, he did not make any enquiries of any company selling the same type of product as he was proposing to sell before choosing a company name. These would have been straightforward steps to take if he wanted to avoid infringing the rights of others.

...

[148] The Australian Securities and Investments Commission website also provided significant information about choosing a company name. It warned company registrants that they did not have the absolute right to use a company name and that they should consider if the proposed name was similar or identical to any registered or pending trade marks. Similar information was also provided by the Australian Government through the website www. business.gov.au."

English position:

The Eastman Phtographic Materials Company, Ltd v. The John Griffiths Cycle Corporation Ltdand the Kodak Cycle Company Ltd [1898] 15 RPC 105:

The registered proprietor of the mark "KODAK" brought an action against the defendant for trade mark infringement and passing off stemming from the defendant's use of the registered mark as part of its trade name. In granting an injunction to restrain the defendant from using the "KODAK" mark as part of its company name, the English High Court decided that:

"I think it would injure the plaintiff company, and would cause the defendant company to be identified with the plaintiff company, or to be recognised by the public as being connected with it, and I think, accordingly, the defendants, The Kodak Cycle Company Ld, ought to be restrained from carrying on business under that name.

Moreover, it appears to me that they ought not to be permitted to sell their cycles under the name of the "Kodak Cycles" for similar reasons. I think it would lead to confusion; I think it would lead to deception, and I think it would be injurious to the plaintiff company."

Indian position:

(a) P Narayanan, Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off, 6th edn, pp 559560:

The learned author P Narayanan commented on the issue viz-a-viz the use of a mark as part of trading style or corporate name as follows:

"The use of a registered trade mark as part of the trading style of another dealing in the same kind of goods will constitute infringement of the mark."

(b) Ellora Industries v. Banarsi Das Goela and Ors [1980] AIR Delhi 254:

The plaintiff was the registered proprietor of the trade mark 'ELORA'. It brought an action against the defendants for trade mark infringement and passing off in respect of the defendants' use of the trade name "Ellora Industries". The Delhi High Court allowed the plaintiff's claim and went on to declare that:

"43. The defendants have caused a part of the plaintiff's reputation to be filched. They have annexed to their business name what is another men's property. The plaintiffs' trade mark "Elora" is the core or the essential part of the defendants' trading style, "Ellora Industries".

...

Thus "E[ll]ora Industries" is an "infringing designation", a misleading name and its use must be restrained by injunction so that the competitor is prohibited from gaining an unfair advantage by confusing potential customers. "The tendency of the law, both legislative and common, has been in the direction of enforcing increasingly higher standards of fairness or commercial morality in trade."

46. The appropriation of the plaintiff's trade mark by the defendants as their own badge is as much a violation of the "exclusive right" of the rival trader as the actual copy of his device. It is a misleading designation. It creates a confusion as to source in the mind of the purchasing public. The words in the defendants' trading style convey a misrepresentation that materially injures the registered proprietor of the trade mark. Many and insidious are the ways of infringement. Sometimes "the falsehood is a little subtler, the injury a little more indirect", than in ordinary cases."

(c) Poddar Tyres Ltd v. Bedrock Sales Corporation Ltd [1993] AIR Bom 237:

The Bombay High Court, in holding the defendant liable for using the plaintiff's registered mark "BEDROCK" as part of the defendant's company name, decided that: