Federal Court, Putrajaya

Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat CJ, Azahar Mohamed CJM, Alizatul Khair Osman Khairuddin, Idrus Harun, Nallini Pathmanathan FCJJ

[Civil Appeal Nos: 01(f)-38-10-2018(W), 01(f)-41-10-2018(W), 02(f)-95-102018(W), 02(f)-96-10-2018(W), 02(f)-97-10-2018(W) & 02(f)-98-10-2018(W)]

26 November 2019

Land Law: Housing development - Sale and purchase agreement - Delivery of vacant possession - Agreement provided for delivery of vacant possession in 36 months - Application by developer for extension of time for delivery of vacant possession - Minister granted extension - Whether decision beyond jurisdiction - Right of purchasers to be heard - Whether decision affected rights of purchasers to claim damages in event of delay

Administrative Law: Judicial review - Exercise of administrative powers - Exercise of discretion - Application by developer for extension of time for delivery of vacant possession under reg 11 Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 ("the Regulations") to the Controller of Housing - Extension of time granted - Application to quash decision by Controller of Housing for Urban Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government amending time period for delivery of vacant possession - Whether decision beyond jurisdiction - Whether the Housing Controller has the power to waive or modify any provision in the Schedule H Contract of Sale as prescribed by the Minister under Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 - Whether s 24 Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 confers power on the Minister to make regulations for the purpose to delegate the power to waive or modify the Schedule H Contract of Sale to the Housing Controller - Whether reg 11(3) Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 is ultra vires Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966

There were six related appeals before the Federal Court wherein four appeals were filed by the purchasers of individual condominium units in Sri Istana Condominium ("the project"). The developer of the project, BHL Construction Sdn Bhd filed the other two appeals. The issue in these appeals concerned reg 11(3) of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 ("the Regulations"). By a Sale and Purchase Agreement dated 3 May 2012 ("the SPA"), entered between the developer and the purchasers, it was agreed that the delivery of vacant possession of the units shall be 36 months from the date of signing of the respective SPAs. They made the SPAs pursuant to the prescribed form under Schedule H of the Regulations. Subparagraph 25(2) of Schedule H provides that if the developer fails to deliver vacant possession within 36 months, the developer shall be liable to pay the purchaser liquidated damages ("LAD"). Vide a letter dated 20 October 2014, the developer applied for an extension of time for the delivery of vacant possession of the units to the purchasers. The application for the extension of time was made to the Controller of Housing ("the Controller"), under reg 11(3) of the Regulations. By a letter dated 24 October 2014, the Controller rejected the developer's application for extension of time. Dissatisfied with the decision of the Controller, the developer, vide a letter dated 28 October 2014, appealed to the Minister of Urban Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government ("the Minister"). The appeal was made pursuant to reg 12 of the Regulations which provides that any person aggrieved by the decision of the Controller may within 14 days after been notified of the decision of the Controller, appeal against such a decision to the Minister; and the decision of the Minister made thereon shall be final and shall not be questioned in any court. The developer's appeal for the extension of time was purportedly allowed by the Minister. By a letter dated 17 November 2015, the Minister purported to grant an extension of 12 months to the developer. The developer thus had 48 months to deliver vacant possession of the condominium units to the purchasers instead of the prescribed period of 36 months. As a result of the extension of time, the purchasers were unable to claim for the LAD as provided for in the SPAs. Aggrieved by the decision of the Minister in granting the extension of time, the purchasers filed an application for judicial review against the Minister; the Controller and the developer. The High Court granted the judicial review application on the main basis that reg 11(3) was ultra vires the Act and that the Controller had no power to waive or modify the contract of sale between the purchasers and the developer. The High Court held that the Controller had no power to waive or modify the prescribed contract of sale under reg 11(3) of the Regulations which extinguished the rights of the purchasers to claim LAD. Aggrieved by the High Court's decision, the developer appealed to the Court of Appeal. The issues raised before the Court of Appeal were: (i) whether reg 11(3) of the Regulations 1989 was ultra vires the Act; (ii) whether the letter of 17 November 2015 was made without jurisdiction and was therefore invalid and of no effect; and (iii) whether the purchasers ought to have been given a right of hearing prior to the decision made by the Controller and/or Minister. The Court of Appeal allowed the developer's appeal. On the first issue, the Court of Appeal found that reg 11(3), being a provision designed to regulate and control the terms of the SPA as envisaged under para 24(2)(e) of the Act, is not ultra vires the Act. The Court of Appeal so held that the Controller has the power to exercise his discretion as granted under reg 11(3), to waive or modify the terms and conditions of the contract of sale. On whether the letter dated 17 November 2015 was invalid and was of no effect, the Court of Appeal held that the order as contained in the letter of 17 November 2015 was made without jurisdiction and was ultra vires the Act and that the order in the said letter was a nullity and of no effect. On whether the purchasers were entitled to a right to be heard, the Court of Appeal found that the purchasers must be given an opportunity to be heard prior to any decision made on the extension of time. Since no such right was afforded to the purchasers, the Court of Appeal held that the decision was null and void and was thus set aside. The developer and purchasers both appealed to the Federal Court. The issues before the Federal Court were (i) whether the Housing Controller has the power to waive or modify any provision in the Schedule H Contract of Sale as prescribed by the Minister under the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966; (ii) whether s 24 of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 confers power on the Minister to make regulations for the purpose to delegate the power to waive or modify the Schedule H Contract of Sale to the Housing Controller; (iii) whether reg 11(3) of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 is ultra vires the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966; and (iv) whether the letter granting an extension of time after an appeal pursuant to reg 12 of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 must be signed personally by the Minister and whether the Minister could delegate his duties (signing of the letter granting the extension of time) to an officer in the Ministry of Urban, Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government of Malaysia.

Held (allowing the purchasers' appeals and dismissing the developer's appeals):

(1) The Controller had no power to waive or modify any provision in the Schedule H contract of sale because s 24 of the Act does not confer power on the Minister to make regulations for the purpose of delegating the power to waive or modify the Schedule H contract of sale to the Controller. Hence, reg 11(3) of the Regulations, conferring power on the Controller to waive and modify the terms and conditions of the contract of sale is ultra vires the Act. Having regard to the object and purpose of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966, the words "to regulate and to prohibit" in subsection 24(2)(e) should be given a strict construction, in the sense that the Minister is expected to apply his own mind to the matter and not to delegate that responsibility to the Controller. The Act being a social legislation designed to protect the house buyers, the interests of the purchasers shall be the paramount consideration against the developer. The legislative intent that the duties shall remain with the Minister, may be discerned from ss 11 and 12 of the Act. Since it is the Minister who is entrusted or empowered by Parliament to regulate the terms and conditions of the contract of sale, the Minister's action in delegating the power to modify the conditions and terms of the contract of sale may be construed as having exceeded what was intended by Parliament. By delegating the power, vide reg 11(3) to the Controller to waive or modify the prescribed terms and conditions of the sale of contract, it was now the Controller who has been entrusted to regulate the terms and conditions of the contract of sale. Further, by modifying the prescribed terms and conditions and by granting the developer the extension of time, the Controller had denied the purchasers' right to claim for LAD. This modification and the granting of extension of time to the developer, did not appear to protect or safeguard the purchasers but rather the developer and this militates the intention of Parliament. (paras 36, 40, 41, 51, 56 & 60)

(2) On the letter dated 17 November 2015 which was to convey the decision of the Minister on the developer's appeal against the rejection by the Controller on the extension of time, the Federal Court held that the letter was not a valid letter granting an extension of time to the developer. The signatory to the letter had stated that he signed the letter on behalf of the Controller and not on behalf of the Minister. Surely this was not something that the signatory could choose to state either he was acting on behalf of the Controller or the Minister because an appeal cannot lie to the Controller against the decision of the Controller. Thus, it was necessary that the letter conveys the decision of the Minister and that the signatory signed on behalf of the Minister. More importantly, if the extension was granted by the Minister pursuant to an appeal against the dismissal by the Controller of the developer's application for extension of time, the applicable regulation is reg 12 and not reg 11. The fact that the letter was signed on behalf of the Controller to convey a decision by the Ministry (as opposed to the Minister) under reg 11, was clear that the decision to grant the extension of time to the developer was that of the Controller and not the Minister. This was fortified by the absence of any material before the court in the form of an affidavit by the Minister to explain the discrepancy and to state that he had indeed decided to allow the developer's appeal under reg 12 for the extension of time. (para 65)

Case(s) referred to:

Carltona, Ltd v. Commissioners Of Works And Others [1943] 2 All ER 560 (refd)

Dene Nation And The Metis Association Of The Northwest Territories v. The Queen [1984] 2 FC 942 (refd)

H Lavender & Sons v. Minister Of Housing And Local Government [1970] 3 All ER 871 (refd)

International Forest Products Ltd v. British Columbia [2006] BCJ No 322 (refd)

McEldowney v. Forde [1969] 2 All ER 1039 (refd)

Menteri Bagi Kementerian Dalam Negeri & Anor v. Jill Ireland Lawrence Bill & Another Appeal [2015] 6 MLRA 629 (refd)

Palmco Holdings Bhd v. Commissioner Of Labour & Anor [1985] 1 MLRA 419 (refd)

Palm Oil Research And Development Board Malaysia & Anor v. Premium Vegetable Oils Sdn Bhd [2004] 1 MLRA 137 (refd)

SEA Housing Corporation Sdn Bhd v. Lee Poh Choo [1982] 1 MLRA 148 (refd)

Sentul Raya Sdn Bhd v. Hariram Jayaram & Ors And Other Appeals [2008] 1 MLRA 473 (refd)

Therrien C Quebec (Minister De La Justice) [2001] 2 RCS 3 (refd)

Veronica Lee Ha Ling & Ors v. Maxisegar Sdn Bhd [2009] 2 MLRA 408 (refd)

Legislation referred to:

Courts of Judicature Act 1964, s 78(1)

Delegation of Powers Act 1956, s 5

Employment (Termination And Lay-Off Benefits) Regulations 1980, reg 8(2)

Employment Act 1955, s 60J(1), (2)

Forest Act, RSBC 1996 [Canada], s 151(1.1), (2)(n)

Housing Development (Control And Licensing) Act 1966, ss 4(2), (3), (4), 10A, 10B, 10C, 10D, 10E, 10F, 11, 12, 24(2)(e)

Housing Development (Control And Licensing) Regulations 1989, regs 11(3), 12

Counsel:

For the appellant: George Varughese (Johan Mohan Abdullah with him); M/s Johan Arafat Hamzah & Mona

For the respondent: KL Wong (Albert KY Soon, Andrew KJ Chan, Viola De Cruz & Koh Kean Kang with him); M/s KL Wong

Watching Brief for REHDA: Mark Ho Hing Kheong (Pang Li Xuan with him); M/s Chellam Wong

Watching Brief for Bar Council: Roger Tan (Nicholas Chang & Elison Wong with him)

JUDGMENT

Tengku Maimun Tuan Mat CJ:

Introduction

[1] There were six related appeals before us which were heard together. Four (4) appeals were filed by the purchasers of individual condominium units in Sri Istana Condominium ("the project"). The other two appeals were filed by the developer of the project, BHL Construction Sdn Bhd. The issue in these appeals concerns reg 11(3) of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 ("the Regulations").

Background Facts

[2] By a Sale and Purchase Agreement dated 3 May 2012 ("the SPA"), entered into between the developer and the purchasers, it was agreed that the delivery of vacant possession of the units shall be 36 months from the date of signing of the respective SPAs. The SPAs were made pursuant to the statutorily prescribed form under Schedule H of the Regulations. Subparagraph 25(2) of Schedule H provides that if the developer fails to deliver vacant possession within 36 months, the developer shall be liable to pay the purchaser liquidated damages ("LAD").

[3] Vide a letter dated 20 October 2014, the developer applied for an extension of time for the delivery of vacant possession of the units to the purchasers. The application for the extension of time was made to the Controller of Housing ("the Controller"), pursuant to reg 11(3) of the Regulations, which reads:

"(3) Where the Controller is satisfied that owing to special "circumstances or hardship or necessity compliance with any of the provisions "in the contract of sale is impracticable or unnecessary, he may, by a certificate in writing, waive or modify such provisions:

Provided that no such waiver or modification shall be approved if such application is made after the expiry of the time stipulated for the handing over of vacant possession under the contract of sale or after the validity of any extension of time, if any, granted by the Controller."

[4] Briefly, the reasons relied upon by the developer in support of its application for extension of time were:

(i) non-stop complaints by nearby residents due to extended working "hours;

(ii) stop work orders issued by the local authorities; and

(iii) investigation conducted on the piling contractor.

[5] By a letter dated 24 October 2014, the Controller rejected the developer's application for extension of time.

[6] Dissatisfied with the decision of the Controller, the developer, vide a letter dated 28 October 2014, appealed to the Minister of Urban Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government ("the Minister"). The appeal was made pursuant to reg 12 of the Regulations which provides:

"Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in these Regulations, any "person aggrieved by the decision of the Controller... may within fourteen "(14) days after been notified of the decision of the Controller, appeal "against such decision to the Minister; and the decision of the Minister made "thereon shall be final and shall not be questioned in any court."

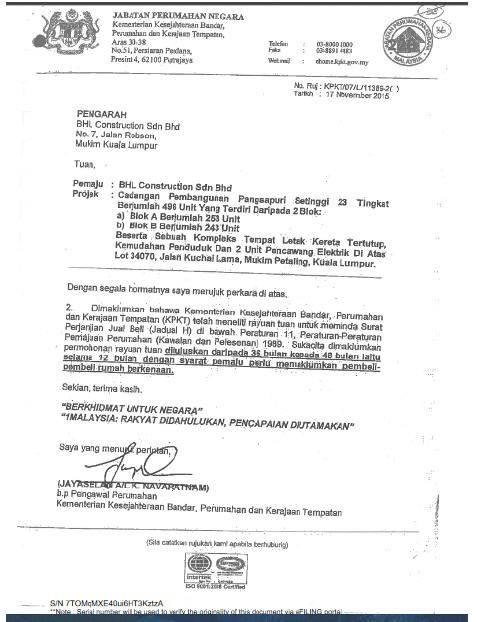

[7] The developer's appeal for the extension of time was purportedly allowed by the Minister. By a letter dated 17 November 2015, the Minister purported to grant an extension of twelve (12) months to the developer. The developer thus had 48 months to deliver vacant possession of the condominium units to the purchasers instead of the statutorily prescribed period of 36 months. As a result of the extension of time, the purchasers were unable to claim for the LAD as provided for in the SPAs.

[8] Aggrieved by the decision of the Minister in granting the extension of time, the purchasers filed an application for judicial review against the Minister; the Controller and the developer.

Proceedings In The High Court

[9] The judicial review application was premised on the following grounds:

(i) that reg 11(3) of the Regulations is ultra vires the Housing "Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 ("the Act");

(ii) that the decision made by the Controller in refusing the extension "of time was non-appealable and that the Minister had no power to hear the "appeal by the developer under reg 12;

(iii) that the Controller and/or the Minister had denied the rights of "the purchasers to be heard, and thus the decision made was null and void;

(iv) that the Minister took into account irrelevant matters in arriving "at his decision to allow the extension of time; and

(v) that the letter dated 17 November 2015 purportedly allowing the "extension of time was signed by one Jayaseelan a/l Navaratnam, on behalf of "the Controller and not on behalf of the Minister.

[10] The purchasers prayed, inter alia for the following reliefs:

(a) an order of certiorari to quash the decision of the Controller dated 17 November 2015;

(b) a declaration either jointly or in the alternative that:

(i) the letter dated 17 November 2015 signed by Jayaseelan a/l K Navaratnam on behalf of the Controller is invalid and is beyond the jurisdiction stipulated in the Act; and

(ii) reg 11(3) of the Regulations is ultra vires the provisions of the Act.

[11] The High Court allowed the judicial review application and granted the orders prayed for by the purchasers. In essence, the High Court ruled that:

(i) the Act is a piece of social legislation intended to protect the interests of the purchasers;

(ii) s 17A of the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967 expressly provides that in interpreting a provision of an Act, a construction that would "promote the purpose or object underlying the Act shall be preferred;

(iii) the Controller has no power to waive or modify the prescribed contract of sale under reg 11(3) of the Regulations which extinguish the "rights of the purchasers to claim LAD;

(i) reg 11(3) is ultra vires the Act; and

(ii) the decision dated 17 November 2015 is null and void.

[12] Dissatisfied with the decision of the High Court, the developer appealed to the Court of Appeal.

Proceedings In The Court Of Appeal

[13] Before the Court of Appeal, parties canvassed inter alia the following issues:

(i) whether reg 11(3) of the Regulations is ultra vires the Act;

(ii) whether the letter of 17 November 2015, in which the extension of 12 months was granted to complete the project, was made without jurisdiction "and is therefore invalid and of no effect; and

(iii) whether the purchasers ought to be given a right of hearing prior to the decision made by the Controller and/or the Minister granting the "developer an extension of time to complete the project.

[14] On the first issue, the Court of Appeal found that reg 11(3), being a provision designed to regulate and control the terms of the SPA as envisaged under para 24(2)(e) of the Act, is not ultra vires the Act. The Court of Appeal noted that the Controller has wide powers under the Act and hence dismissed the purchasers' contention that the power to modify or waive the contract must be exercised only by the Minister and cannot be delegated to the Controller. The Court of Appeal accordingly held that the Controller has the power to exercise his discretion as granted under reg 11(3), to waive or modify the terms and conditions of the contract of sale.

[15] On whether the letter dated 17 November 2015 was invalid and was of no effect, the Court of Appeal noted that the said letter was signed by Jayaseelan a/l K Navaratnam on behalf of the Controller and that there was no indication from the face of the letter that this decision was conveyed on behalf of the Minister or that the signatory of the letter was acting on the authority of the Minister. The Court of Appeal stated that ‘to muddy the waters further', the letter indicated that the decision was made pursuant to reg 11 instead of reg 12.

[16] The Court of Appeal further stated that The impression gained from considering the whole of the letter is that the appeal from the decision of the Controller was decided by the Controller himself which, to put it mildly, was wholly untenable. Under reg 12, any person aggrieved with the decision of the Controller under reg 11(3) can appeal to the Minister and the decision of the Minister is final and shall not be questioned in any court. Since the Minister did not file any affidavit to provide some clarity, the contention that the Minister was not the one who made the decision has merit and cannot be dismissed lightly". It was accordingly held by the Court of Appeal that the order as contained in the letter of 17 November 2015 was made without jurisdiction and was ultra vires the Act and that the order in the said letter was a nullity and of no effect.

[17] On whether the purchasers were entitled to a right to be heard, the Court of Appeal agreed with the submission for the purchasers that as their rights to claim damages in the event of delay would be adversely affected or even extinguished, the purchasers must be given an opportunity to be heard prior to any decision made on the extension of time. Since no such right was afforded to the purchasers, the Court of Appeal held that the decision was null and void and was thus set aside.

[18] Aggrieved by the decision of the Court of Appeal, both the purchasers and the developer applied for leave to appeal to this court.

Proceedings In The Federal Court

[19] Leave to appeal was granted to the purchasers on the following questions of law:

(i) whether the Housing Controller has the power to waive or modify any "provision in the Schedule H Contract of Sale as prescribed by the Minister "under the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 ("Question 1");

(ii) whether s 24 of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act "1966 confers power on the Minister to make regulations for the purpose to "delegate the power to waive or modify the Schedule H Contract of Sale to the "Housing Controller ("Question 2");

(iii) whether reg 11(3) of the Housing Development (Control and "Licensing) Regulations 1989 is ultra vires the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 ("Question 3").

[20] The developer was granted leave to appeal on the following questions of law:

(i) whether the letter granting an extension of time after an appeal "pursuant to reg 12 of the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 must be signed personally by the Minister and whether the Minister could delegate his duties (signing of the letter granting the extension of time) to an officer in the Ministry of Urban, Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government of Malaysia ("Question 4");

(ii) whether the Minister having taken into consideration the interest of the purchasers is obliged to afford the purchasers a hearing prior to the Minister granting the extension of time albeit there is no such provision or requirement in the Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Act 1966 or Housing Development (Control and Licensing) Regulations 1989 ("Question 5").

The Parties' Contention

[21] The submission for the developer may be summarised as follows:

(i) that the Minister has the absolute discretion to make a decision in respect of an appeal as per the specific provision of reg 12;

(ii) that the Minister's decision was anchored upon a thorough consideration of all the facts and relevant circumstances, especially the ‘protection of the interest of the purchasers and for matters connected therewith' as stated in the Preamble to the Act;

(iii) that the main objective of the Act is to ensure that housing units are completed and delivered to the purchasers;

(iv) that the Minister's decision to allow the extension of time for delivery of vacant possession, enabled the developer to complete the "development and deliver vacant possession to the purchasers;

(v) that the rehabilitation of abandoned housing projects is a complex process and could take a long time; and

(vi) that an abandoned development would cause greater hardship to the purchasers, which far outweighs the hardship of not being able to claim damages for late delivery, if an extension is granted.

[22] For the purchasers, the gist of the arguments were:

(i) under the Act, both the Minister and the Controller have separate and independent role;

(ii) as a general rule, the powers of the Minister may not be delegated to the Controller unless it is expressly provided under the Act;

(iii) section 24(2) of the Act expressly confers power to the Minister to make regulation for the purpose of prescribing the statutory form for the contract of sale;

(iv) the Minister is also authorised to prescribe regulation for the purpose of regulating the terms and conditions of the contract of sale "between the developer and purchasers;

(v) the word ‘regulate' is not defined in the Act;

(vi) the word ‘regulate' ordinarily means ‘to control or to govern'; and

(vii) it was not the intention of Parliament to authorise the Minister to delegate the power to prescribe and to control and govern to the Controller.

Our Decision

[23] Having read the appeal records and the written submissions filed by the purchasers and the developer and having heard the oral submissions of learned counsel for the purchasers and the developer, respectively as well as counsel holding watching briefs for the Real Estate and Housing Developers' Association (REHDA) Malaysia and the Bar Council (both REHDA and the Bar Council supported the position taken by the developer), we answer the first two questions in the negative and the third question in the affirmative.We find no necessity to answer questions four and five. Our reasons are set out below.

The Validity Of Regulation 11(3) Of The Regulations

[24] Questions 1, 2 and 3 concern the validity of reg 11(3) of the Regulations and as such, we will consider them together. We begin by setting out the following provisions of the Act:

"4. Appointment of Controller, Deputy Controllers, Inspectors and other officers and servants.

(1) For the purpose of this Act, the Minister may appoint a Controller of Housing and such number of Deputy Controllers of Housing, Inspectors of "Housing and other officers and servants as the Minister may deem fit from amongst members of the civil service.

11. Powers of the Minister to give directions for the purpose of safeguarding the interests of purchasers.

(1) Where on his own volition a housing developer informs the Controller or where as a result of an investigation made under s 10 or for any other reason the Controller is of the opinion that the licensed housing developer becomes unable to meet his obligation to his purchasers or is about to suspend his building operations or is carrying on his business in a manner "detrimental to the interests of the purchasers, the Minister may without "prejudice to the generality of the powers of the Minister to give directions under s 12 for the purpose of safe-guarding the interests of the purchasers of the licensed housing developer-

(a) ...

(b) ...

(c) ...

(d) ...

(e) take such action as the Minister may consider necessary in the circumstances of the case for carrying into effect the provisions of this Act.

24. Power to make regulations

(1) Subject to this section, the Minister may make regulations for the purpose of carrying into effect the provisions of this Act.

(2) In particular and without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing power, the regulation may-

(a) ....

(b) ....

(c) prescribe the form of contents which shall be used by a licensed housing developer, his agent, nominee or purchaser both as a condition of the grant of a license under this Act or otherwise;

(d) ...

(e) regulate and prohibit the conditions and terms of any contract between a licensed housing developer, his agent or nominee and his purchaser;"

[25] Section 24(2) of the Act empowers the Minister to prescribe the statutory form of contract for the sale and purchase agreement between the developer and the purchasers and to regulate the terms and conditions of the contract of sale. Pursuant to subsection 24(2) of the Act, the Minister promulgated the Regulations prescribing the statutory form for the contract of sale in Schedule H together with the conditions and terms of such contract.

[26] Having prescribed the Statutory Form H and the terms and conditions for the contract of sale, the Minister by reg 11(3) of the Regulations then empowers the Controller to waive or modify the conditions and terms of the contract of sale as prescribed in Schedule H. This begs the question whether by empowering the Controller to waive or modify the conditions and terms of the contract, the Minister has exceeded the scope of the authority conferred on him by the legislature? In other words, by empowering the Controller, through reg 11(3), has there been an act of sub-delegation by the Minister to the Controller which is ultra vires the Act?

[27] De Smith's Judicial Review 7th edn, stated as follows on the rule against delegation:

"A discretionary power must, in general, be exercised only by the public authority to which it has been committed. It is a well-known principle of law that when a power has been conferred to a person in circumstances indicating that trust is being placed in his individual judgment and "discretion he must exercise that power personally unless he has been expressly empowered to delegate it to another.... it is a rule of construction which makes the presumption that a discretion conferred by statute is prima facie intended to be exercised by the authority on which the statute has conferred it and by no other authority, but this presumption may be rebutted by any contrary indications found in the language, scope or object of the statute."

[28] Sir William Wade & Christopher Forsyth in the Administrative Law 11th edn, stated:

"An element which is essential to the lawful exercise of power is that it should be exercised by the authority upon whom it is conferred, and by no one else. The principle is strictly applied, even where it causes administrative inconvenience, except in cases where it may reasonably be inferred that the power was intended to be delegable. Normally the courts are rigorous in requiring the power to be exercised by the precise person or body stated in the statute, and in condemning as ultra vires action taken by agents, sub-committee or delegates, however expressly authorised by the authority endowed with the power.

...

The maxim delegatus non potest delegare is sometimes invoked as if it embodied some general principle that made it legally impossible for statutory authority to be delegated. In reality there is no such principle; the maxim plays no real part in the decision of cases, though it is sometimes used as a convenient label. In the case of statutory powers, the "important question is whether on a true construction of the Act, it is "intended that a power conferred upon A may be exercised on A's authority by B. The maxim merely indicates that this is not normally allowable.... The vital question in most cases is whether the statutory discretion remains in the hands of the proper authority, or whether some other person purports to exercise it."

[29] In Palmco Holdings Bhd v. Commissioner Of Labour & Anor [1985] 1 MLRA 419, the issue relates to s 60(J)(1) of the Employment Act 1955 and reg 8(2) of the Employment (Termination and Lay-Off Benefits) Regulations 1980. Section 60J(1) reads:

"The Minister may, by regulation made under the Act, provide for the entitlement of employees to, and for the payment by the employer of-

(a) termination benefits;

(b) lay-off benefits;

(c) retirement benefits."

Whereas reg 8(2) of the Employment (Termination and Lay-Off Benefits) Regulations 1980 reads as follows:

"If the person by whom the business is to be taken over immediately after the change occurs does not offer to continue to employ the employee in accordance with paragraph (1), the contract of service of the employee shall be deemed to have been terminated, and consequently, the person by whom the employee was employed immediately before the change in ownership occurs and the person by whom the business is taken over immediately after the change occurs shall be jointly and severally liable for the payment of all termination benefits payable under these Regulations."

[30] In Palmco Holdings (supra), the appellant had bought over the business of a beach hotel in Penang from the Casuarina Beach Hotel Sdn Bhd. It was agreed inter alia that the appellant would offer employment to all existing employees of the hotel except five persons who had passed the retirement age and were relatives of the family who were the former owners of the hotel. The five persons applied to the Director of Labour for termination benefits but the hearing of the application was adjourned to enable the appellant to challenge the vires of reg 8 of the Employment (Termination and Lay-Off Benefits) Regulations 1980. It was argued that the regulation was ultra vires as it sought to impose liability on persons other than employers and therefore contravened s 60J(1) of the Employment Act 1955, which only enables the Minister to make regulations for the payment of termination, lay-off and retirement benefits by employers. The learned trial judge held that reg 8 was not ultra vires the Employment Act 1955. The appellant appealed.

[31] In allowing the appeal, Hashim Yeop A Sani SCJ said:

"The powers of the courts on the question of determining the vires of a delegated legislation were summed up by Lord Greene MR in Carltona Ltd v. Commissioners of Works which was followed in Lewisham BC v. Roberts and Minister of Agriculture & Fisheries v. Matthews where His Lordship said:

"All that the court can do is to see that the power which it is claimed to exercise is one which falls within the four corners of the powers given by the legislature and to see that the powers are exercised in good faith. Apart from that the courts have no power at all to enquire into the reasonableness, the policy, the sense or any other aspect of the transaction."

What the court should do in the case of this nature are also clearly and "precisely explained by Lord Diplock in McEldowney v. Forde where he said:

"Parliament makes law and can delegate part of its power to do so to some subordinate authority. The courts construe law whether made by Parliament directly or by a subordinate authority acting under delegated legislative powers. The view of the courts as to whether particular statutory or subordinate legislation promotes or hinders the common weal is irrelevant. The decision of the courts as to what the words used in the statutory or subordinate legislation mean is decisive. Where the validity of subordinate legislation made pursuant to powers delegated by Act of Parliament to a subordinate authority is challenged, the court has a three-fold task: first, to determine the meaning of the words used in the Act of Parliament itself to describe the subordinate legislation which that authority is authorised to make, secondly, to determine the meaning of the subordinate legislation itself and finally to decide whether the subordinate legislation complies with that description."

...

The term ultra vires in relation to a delegated legislation can be interpreted in a double sense. First it can mean that the rule or regulation in question deals with a subject not within the scope of power conferred upon the delegated legislative authority. Second, it can also mean that although the delegated legislation in question deals with the proper subject it has gone beyond the limits prescribed by the parent law ...

Section 60J(2) of the Employment Act provides that without prejudice to "the generality of sub-section (1) regulations made by virtue of subsection (1) may provide inter alia:

"(a) for the definition of the expression "termination benefits", "layoff benefits", or "retirement benefits", as the case may be, and for the circumstances in which the same shall be payable."

Basically the word "employer" in the Act means any person who has entered into a contract of service to employ another person as an employee. In our view it is clear that the powers conferred by s 60J(1) and (2) of the Act are not wide enough to cover a person who is not an employer. The person by "whom the business is taken over immediately after the change occurs (these words appear in reg 8(2)) is not an employer as defined in the Act. The "imposition of liability on that person is never envisaged by the Parent Act. "As in the case of Morton v. Union Steamship Co of New Zealand Ltd the purpose of the Act is to impose liability upon a set of persons whereas the regulation purports to impose a liability upon another set of persons never "intended by the Legislature."

[32] Similar issue on delegation of power was dealt with by the Federal Court in Palm Oil Research And Development Board Malaysia & Anor v. Premium Vegetable Oils Sdn Bhd [2004] 1 MLRA 137. Pursuant to the Palm Oil (Research Cess) Order 1979 ("the 1979 Order") made by the Minister under the Palm Oil Research and Development Act 1979 ("the 1979 Act"), the appellants imposed research cess ("cess") on the respondent in respect of crude oil extracted from oil palm fruits ("CPO") and also in respect of crude oil extracted from oil palm kernel (CPKO"). The respondent did not dispute the imposition of cess on CPO but disputed the imposition of cess on CPKO. It brought an action in the High Court for a declaration that the appellants were not empowered to impose cess on CPKO and for a refund of the money paid. It was contended by the respondent that the 1979 Act and the 1979 Order made no reference to crude oil extracted from oil palm fruits and seeds. The appellants, on the other hand, contended that the kernel was part of the oil palm seed. As such, they had the right to impose cess on the CPKO.

[33] The High Court ruled against the respondent. The decision of the High Court was reversed by the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal held that cess could only be imposed on CPO and not on CPKO. The appellants obtained leave to appeal to the Federal Court.

[34] The central question before the Federal Court was whether the 1979 Order was ultra vires the parent statute, namely the 1979 Act. In addressing the issue, Gopal Sri Ram FCJ said:

"To recapitulate, the first submission is that the 1979 Act does not authorise the collection of cess from palm oil millers. To determine if there is merit in the complaint, all that is necessary is to examine the Act itself. There is no dispute - indeed there cannot be any - that the 1979 Act does not define the term "palm oil miller". Section 14(1) by which Parliament delegates subsidiary law making authority to the Minister reads "as follows:

14(2) The Minister may, after consultation with the Board and with the Minister of Finance, make orders for the imposition, variation or cancellation of a research cess on palm oil; and the orders may specify the nature, amount and rate and the manner of collection of the cess.

Be it noted that the section empowers the Minister, inter alia, to impose research cess on palm oil, not on palm oil millers. The point of construction here is therefore uncomplicated and straightforward. The 1979 Act did not give the Minister power to make orders imposing a research cess on palm oil millers. And it is not open to this court to read into the section an implied power enabling the Minister to do so. Such a course would constitute unauthorised judicial legislation and a breach of the doctrine of separation of powers enshrined in the Federal Constitution.

First, the 1979 Act does not authorise the imposition of the research cess upon palm oil millers. Second, s 14 of the 1979 Act does not impose any liability upon oil palm millers to pay research cess. Based on these matters "it is my considered judgment that the 1979 Order is ultra vires the "1979 Act. The 1979 Order is therefore null and void and of no effect."

[35] Having in mind the principles enunciated in the above cited cases on delegated legislation, we now proceed to ascertain the powers of the Minister and the Controller under the Regulations, by undertaking the first task as laid down in McEldowney v. Forde [1969] 2 All ER 1039, ie to determine the meaning of the words used in the Act.

[36] By s 24(2)(e) of the Act, the Minister is empowered or given the discretion by Parliament to regulate and prohibit the terms and conditions of the contract of sale. As opined by the learned authors in De Smith's Judicial Review, a discretion conferred by statute is prima facie intended to be exercised by the authority on which the statute has conferred it and by no other authority, but the presumption may be rebutted, by any contrary indication found in the language, scope or object of the Act. In our view, having regard to the object and purpose of the Act, the words "to regulate and to prohibit" in subsection 24(2)(e) should be given a strict construction, in the sense that the Minister is expected to apply his own mind to the matter and not to delegate that responsibility to the Controller.

[37] The object of the Act has been highlighted in a string of authorities. In SEA Housing Corporation Sdn Bhd v. Lee Poh Choo [1982] 1 MLRA 148, Suffian LP said at p 152:

"It is common knowledge that in recent years especially when the Government started giving housing loan making it possible for public servants to borrow money at 4% interest to buy homes, there was an upsurge in demand for housing, and that to protect home buyers, most are whom are people of modest means, from rich and powerful developers, Parliament found it necessary to regulate the sale of houses and protect buyers by enacting the Act."

[38] In the case of Sentul Raya Sdn Bhd v. Hariram Jayaram & Ors And Other Appeals [2008] 1 MLRA 473, Gopal Sri Ram JCA (as he then was) speaking for the Court of Appeal said:

"The contract which has fallen for consideration in the present case is a "special contract. It is prescribed and regulated by statute. While parties in normal cases of contract have freedom to make provisions between themselves, a housing developer does not enjoy such freedom. Hence parties "to a contract in Form H cannot contract out of the scheduled form. Terms "more onerous to a purchaser may not be imposed. So too, terms imposing "additional obligations on the part of a purchaser may not be included in the statutory form of contract."

[39] The Federal Court in Veronica Lee Ha Ling & Ors v. Maxisegar Sdn Bhd [2009] 2 MLRA 408, reiterated the object of the Act by making the following observation:

"Now, cl 23 is part of a statute based contract. In this country, the relationship between a house-buyer and a licensed developer is governed by the Housing Developers legislation. Its object is to protect house buyers against developers. A developer must execute the agreement set out in the schedule to the relevant subsidiary legislation. He cannot add other clauses in it."

[40] The Act being a social legislation designed to protect the house buyers, the interests of the purchasers shall be the paramount consideration against the developer. Parliament has entrusted the Minister to safeguard the interests of the purchasers and the Minister has prescribed the terms and conditions of the contract of sale as per Schedule H. We find no contrary indication in the language, scope or object of the Act that such duty to safeguard the interests of the purchasers may be delegated to some other authority.

[41] The legislative intent that the duties shall remain with the Minister, may be discerned from ss 11 and 12 of the Act. Under s 11, whilst the Controller is given the power to investigate on the reason why a licensed housing developer is unable to meet his obligation to the purchasers, or is about to suspend his building operations or is carrying on his business detrimental to the interests of the purchaser, it is the Minister who is empowered to give directions and to take such other measures for purposes of safeguarding the interests of the purchasers and for carrying into effect the provisions of the Act. Likewise under s 12 which provides for the powers of the Minister to give general directions as he considers fit, to the licensed housing developer for purposes of ensuring compliance with the Act. Such directions, which shall be given in writing, are binding on the developer.

[42] We now move to the second task ie to determine the meaning of the words in the Regulations. In this regard, the first point to observe is that notwithstanding the prescribed time line under Form H for the developer to complete the project, the Regulations provide for an extension of time. As regards the extension of time, the Regulations provide for a two-tier structure. The first tier is found in reg 11(3) where at the first instance, the Controller is empowered to decide on an application for extension of time. Once a decision is made by the Controller, any aggrieved party may appeal to the Minister under reg 12, which is the second tier for the appeal process.

[43] It was argued for the developer that the Minister has delegated his power to the Controller to make a decision under reg 11(3). This argument in our view cannot be sustained. If the Minister has delegated his power to the Controller to make a decision under reg 11(3), there should not and could not be an appeal process from the decision of the Controller to the Minister as it is akin to an appeal to the Minister against his own decision. Regulation 12 on the appeal would be rendered superfluous and redundant.

[44] Insofar as delegation of powers is concerned, we are mindful of s 5 of the Delegation of Powers Act 1956, which reads:

"Where by any written law a Minister is empowered to exercise any powers "or perform any duties, he may, subject to s 11, by notification in the Gazette delegate subject to such conditions and restrictions as may be prescribed in such notification the exercise of such powers or the "performance of such duties to any person prescribed by name or office."

[45] It must be noted that while s 5 expressly allows the Minister to delegate his powers or duties to any person described by name or office, such delegation must be made by notification in the Gazette. In the present case, we observe that there is no notification published in the Gazette which means that there is no delegation of powers by the Minister to any other person of his duties under the Act pursuant to the Delegation of Powers Act.

[46] In Therrien v. Quebec (Minister de la Justice) [2001] 2 RCS 3, Gonthier J said:

"It is settled law that a body to which a power is assigned under its "enabling legislation must exercise that power itself and may not delegate it to one of its members or to a minority of those members without the express or implicit authority of the legislation, in accordance with the maxim hallowed by long use in the courts, delegatus non potest delegare:.."

[47] Wills J in H Lavender & Sons v. Minister of Housing and Local Government [1970] 3 All ER 871, quashed a decision to refuse planning permission within reservation area if the Minister of Agriculture objected. His Lordship stated that "I think the Minister of Housing and Local Government has fettered himself in such a way that in this case it was not he who made the decision for which Parliament made him responsible."

[48] In Dene Nation and the Metis Association of the Northwest Territories v. The Queen [1984] 2 FC 942, the Northern Inland Waters Act, RSC 1970 (1st Supp) c 28, prohibits, subject to certain exceptions, the alteration of the flow, storage or other use of water within a water management area except pursuant to a licence issued by a board or when authorised by regulations. The relevant regulation-making authority for the latter is found in para 26(g) of the Act and it reads:

"26. The Governor in Council may make regulations ... (g) authorising the use without a licence of waters within a water management area

(i) for the use, uses or class of uses specified in the regulations,

(ii) in a quantity or at a rate not in excess of a quantity or rate specified in the regulations, or

(iii) for a use, uses or class of uses specified in the regulations and in a quantity or at a rate not in excess of a quantity or rate specified therein."

Section 11 of Regulations SOR/72-382, as amended by SOR/75-421, promulgated pursuant to that authority provides:

"11. Water may be used without a licence having been issued if the controller has stated in writing that he is satisfied that the proposed use would meet the applicable requirements of subsection 10(1) of the Act if an application described in that section for that use were made and

(a) the proposed use is

(i) for municipal purposes by an unincorporated settlement; or

(ii) for water engineering purposes;

(b) the proposed use will continue for a period of less than 270 days; or

(c) the quantity proposed to be used is less that 50,000 gallons per day."

[49] The plaintiffs brought an action seeking for a declaration that s 11 and the authorisations issued thereunder were invalid. The plaintiffs' argument was based on mainly three grounds:

(i) that s 11 of the Regulations is invalid because its scope and breadth is such as to undercut the whole purpose of the statute;

(ii) the discretion given to the controller by s 11 is not authorised by para 26(g); and

(iii) that at the very least paragraph (b) of s 11 is ultra vires because it is not a regulation respecting the ‘quantity' or ‘rate' of water used, as provided in para 26(g), but prescribes only a time period during which an authorisation will run.

[50] Reed J said:

"It is useful to begin with a description of the general scheme of the Act. Section 7 provides for the establishment of two boards: the Yukon Territory Water Board and the Northwest Territories Water Board ...

Parliament clearly intended two procedures for authorizing water uses: one through the Yukon and Northwest Territories Water Boards, exercising the quasi-judicial and discretionary powers which such bodies characteristically exercise. The other through regulation in which it was clearly intended that all requirements be met in order to use water without a licence would be specifically and exhaustively set out by the Governor in Council in the Regulations. There is nothing in the Act from which one can infer any intention that part or all of that power should be conferred on a sub-delegate to be exercised in a discretionary fashion. The principle enunciated in Brant Dairy Co Ltd et al v. Milk Commission of Ontario et al, [1973] SCR 131 is very much in point: when authority is conferred on an entity to regulate by regulation, the power must be so exercised and not exercised by setting up some sub-delegate with discretionary powers to make the decision."

[51] Similarly here. It is the Minister who is entrusted or empowered by Parliament to regulate the terms and conditions of the contract of sale. The Minister, however has delegated the power to regulate to the Controller by reg 11(3) of the Regulations. As power to regulate does not include power to delegate, the Minister's action in delegating the power to modify the conditions and terms of the contract of sale may be construed as having exceeded what was intended by Parliament.

[52] By comparison, in International Forest Products Ltd v. British Columbia [2006] BCJ NO 322, the Lieutenant Governor in Council has the statutory authority to pass regulations concerning scaling. Section 151(2)(n) of the Forest Act, RSBC 1996, c 157 provides:

"Without limiting subsection (1), the Lieutenant Governor in Council may "make regulations respecting any or all of the following:

(n) scaling including, without limitation, (i) regulations authorized "under Part 6;

(ii) the timing of a scale;

(iv) the payment of estimated stumpage; and

(v) scale site authorizations ..."

[53] The Lieutenant Governor in Council also has express statutory authority to delegate matters to other persons. Section 151(1.1) of the Forest Act provides:

"In making a regulation under this Act, the Lieutenant Governor in "Council may do one or more of the following:

(a) delegate a matter to a person;

(b) confer a discretion on a person..."

[54] The issue in International Forest Products (supra) concerns s 96(1) of the Act which provides that "A person who scales or purports to scale timber under this Act (a) must carry out the scale according to the prescribed procedures ...". The British Columbia Supreme Court held that the impugned s 96(1)(a) does not interfere with the Lieutenant Governor in Council's express statutory authority to delegate a matter or confer a discretion on a person (including in relation to scaling). Understandably so, because as regards delegation, the power to delegate is expressly provided for, whereas in our instant appeals and Dene Nation (supra), there was absent such express power to delegate.

[55] Finally, on the third task. In the instant appeals, the Schedule H contract of sale prescribed by the Regulations is to carry into effect the provisions of the Act, which is to protect the interests of the purchasers. The regulations made by the Minister must thus achieve the object of protecting the interests of the purchasers and not the interests of the developers. And at the risk of repetition, the duty to protect the interests of the purchasers is entrusted to the Minister.

[56] By delegating the power, vide reg 11(3) to the Controller to waive or modify the prescribed terms and conditions of the sale of contract, it is now the Controller who has been entrusted to regulate the terms and conditions of the contract of sale. Further, by modifying the prescribed terms and conditions and by granting the developer the extension of time, the Controller has denied the purchasers' right to claim for LAD. This modification and the granting of extension of time to the developer, does not appear to us to protect or safeguard the purchasers but rather the developer and this militates the intention of Parliament.

[57] It was submitted for the developer that the purchasers would suffer greater hardship if the project is not completed as compared to not being able to claim for LAD. With respect, we fail to see the merit of this submission. If the developer fails to obtain an extension of time to deliver vacant possession, that in itself does not mean that the developer has failed to complete and hence, have abandoned the project. Whether or not the developer is granted an extension of time does not necessarily determine the fate of the project. The extension of time only determines payment of LAD. In this regard, we must not lose sight of the purchasers' obligations to pay for progress instalment to their respective housing financier and/or payment of rental to their landlord. It is a matter of balancing the commercial interest of a multi-million housing development company against the life-time loan commitment of a purchaser for a basic living necessity. As can be seen from the long line of authorities, it is the interests of the purchasers that prevail over that of the developer. We therefore hold that in allowing the Controller to waive or modify the terms and conditions of the contract of sale and in the process, denying the purchasers' right to claim for LAD as prescribed by the Minister under Schedule H, reg 11(3) does not comply with the description of the Regulations which is designed to protect the interests of the purchasers.

[58] There is one other aspect of the legislation that must be noted, namely that the Act has specifically enumerated the respective duties and powers of the Minister, the Controller and an Inspector. The management of the Housing Development Account is under the purview of the Controller. Specific powers of an Inspector can be found in ss 10A, 10B, 10C, 10D, 10E and 10F, whilst powers to give directions for the purpose of safeguarding the interests of purchasers are specifically given to the Minister. Where powers or duties may be exercised by either the Controller or an Inspector, that has been made clear by the Act. For instance, under s 10, either the Controller or an Inspector, on his own volition or upon being directed by the Minister, may investigate the commission of any offence under the Act or investigate into the affairs of or into the accounting or other records of any housing developer.

[59] The powers and duties of the Minister, the Controller and an Inspector, respectively had thus been clearly defined. It is also pertinent to highlight, that by s 4(2), express provisions were made for the exercise of an Inspector's powers by the Controller. By subsections (3) and (4) of s 4, Parliament had expressly allowed for the delegation of the Controller's powers to named persons. But there is no such provision enabling the Controller to exercise the Minister's powers. This supports our view that Parliament did not intend for the Minister's powers to regulate the terms and conditions of a contract of sale to be delegated to the Controller.

[60] On the above analysis, we hold that the Controller has no power to waive or modify any provision in the Schedule H contract of sale because s 24 of the Act does not confer power on the Minister to make regulations for the purpose of delegating the power to waive or modify the Schedule H contract of sale to the Controller. And it is not open to us to read into the section an implied power enabling the Minister to do so. We consequently hold that reg 11(3) of the Regulations, conferring power on the Controller to waive and modify the terms and conditions of the contract of sale is ultra vires the Act.

Question 4 - Whether The Letter Granting An Extension Of Time After Appeal Pursuant To Regulation 12 Of The Housing Development (Control And Licensing) Regulations 1989 Must Be Signed Personally By The Minister? And Whether The Minister Could Delegate His Duties (Signing Of The Letter Granting The Extension Of Time) To An Officer In The Ministry Of Urban, Wellbeing, Housing And Local Government?

[61] We accept that generally, a Minister need not sign a letter personally. As stated by Lord Greene, MR in Carltona, Ltd v. Commissioners of Works and Others [1943] 2 All ER 560:

"In the administration of Government in this country the functions which are given to ministers (and constitutionally properly given to ministers because they are constitutionally responsible) are functions so multifarious that no minister could ever personally attend to them. To take the example of the present case no doubt there have been thousands of requisitions in this country by individual ministers. It cannot be supposed that this regulation meant that, in each case, the minister in person should direct his mind to the matter. The duties imposed upon ministers and the powers given to ministers are normally exercised under the authority of the ministers by responsible officials of the department. Public business could not be carried on if that were not the case. Constitutionally, the decision of such an official is, of course, the decision of the minister. The minister is responsible ..."

[62] In the instant appeals however, we find that the issue is not so much that the Minister did not sign the letter personally, but whether, on the face of the letter, it was the Minister's decision made under reg 12 and whether it was in fact signed by the officer on behalf of the Minister.

[63] The said 17 November 2015 letter purportedly granting extension of time to the developer is reproduced below for ease of reference:

[64] The developer essentially took the position that the extension of time was granted by the Minister and that the letter could have been written better, but that the problem only lies with the choice of words. It was submitted for the developer that the Controller was merely conveying the decision of the Minister to allow the appeal vide the said letter. With respect, we disagree with the developer. The letter dated 17 November 2015 borne out two points. Firstly, it was signed by Jayaseelan on behalf of the Controller and not on behalf of the Minister and secondly, the letter did not state that the decision to grant the extension of time was made by the Minister under reg 12, but it was specifically stated that the decision was made by the Ministry under reg 11.

[65] Taking a closer look at the letter dated 17 November 2015 which was to convey the decision of the Minister on the developer's appeal against the rejection by the Controller on the extension of time, it is our judgment that the letter was not a valid letter granting an extension of time to the developer. The invalidity has nothing to do with the choice of words but it has to do with the substance of the letter, namely the signatory to the letter has stated that he signed the letter on behalf of the Controller and not on behalf of the Minister. Surely this is not something that the signatory can choose to state either he is acting on behalf of the Controller or the Minister because an appeal cannot lie to the Controller against the decision of the Controller. Thus, it is necessary that the letter conveys the decision of the Minister and that the signatory signed on behalf of the Minister. More importantly, if the extension was granted by the Minister pursuant to an appeal against the dismissal by the Controller of the developer's application for extension of time, the applicable regulation is reg 12 and not reg 11. The fact that the letter was signed on behalf of the Controller to convey a decision by the Ministry (as opposed to the Minister) under reg 11, in our view made it crystal clear that the decision to grant the extension of time to the developer was that of the Controller and not the Minister. Our view is fortified by the absence of any material before the court in the form of an affidavit by the Minister to explain the discrepancy and to state that he had indeed decided to allow the developer's appeal under reg 12 for the extension of time.

[66] In this regard, we respectfully endorse the decision of the Court of Appeal in Menteri Bagi Kementerian Dalam Negeri & Anor v. Jill Ireland Lawrence Bill & Another Appeal [2015] 6 MLRA 629, where on similar issue, it states:

"[24] It was also argued before us by learned SFC that the evidence as per the relevant affidavits had shown that the letter dated 7 July 2008, although signed by Suzanah bte Hj Muin, a Senior Authorised Officer, ("Suzanah"), "she had so signed as she was just communicating the decision of the Minister to the applicant. In other words, Suzanah did not decide under s 9 but that "she was only informing or conveying to the applicant what had been decided by the Minister ...

[25] As such, it was argued before us by learned SFC that the learned judge had erred when she found as a fact that the decision under s 9 had "been made by Suzanah instead of it having been made by the Minister.

[26] In this regard, we had to look at the letter dated 7 July 2008 "itself to see whether such submission by learned SFC could be sustained. That letter ... was clearly signed by Suzanah bte Hj. Muin, a Senior Authorised Officer, from the Home Affairs Ministry. Paragraph 2 of the letter said that in exercise of the powers under s 9(1) of the Act, the Ministry ("Kementerian") had decided to withhold the publications as appeared in the Annexure ‘K' for reasons as stated therein. It was signed off by Suzanah.

[27] Learned SFC had tried to impress upon us that this decision was made by the Minister himself and that Suzanah was only instructed to convey that decision made by the Minister. We were, as was the learned judge, referred to the affidavit of then Minister which according to the learned SFC would dispel all doubts surrounding the decision maker in this case. First, we need only say that there was nothing stated in the letter dated 7 July 2008 that would convey the meaning that Suzanah was directed by the Minister to convey the Minister's decision on the fate of the publications. Secondly, para 2 spoke of the decision of the ‘Kementerian' as opposed to decision of the ‘Minister' as envisage by s 9 of the Act ...".

[33] The nett result of this conclusion by us, would mean that the letter dated 7 July 2008 that purported to confiscate the eight publications belonging to the applicant is one that was bad in law. It was done ultra vires s 9 of the Act as it was made by a person, to wit Suzanah bte Hj Muin, who was not the person who was envisaged by Parliament as the competent person who was empowered to make that order under s 9 of the Act."

[67] On the facts of this case, there being no decision by the Minister under reg 12, we decline to answer Question 4.

Question 5 - Whether The Minister Having Taken Into Consideration The Interest Of The Purchaser Is Obliged To Afford The Purchaser With A Hearing Prior To The Minister Granting An Extension Of Time Albeit There Is No Such Provision Or Requirement In The Housing Development (Control And Licensing) Regulations 1989?

[68] Question 5 is framed on the premise that it was the Minister who had granted the extension of time and that in doing so, he had taken into consideration the interest of the purchasers. As held above, there was no decision by the Minister to grant the extension of time. Question 5 is thus premised on an erroneous fact. We therefore find no necessity to answer Question 5.

Conclusion

[69] To conclude, we would answer the Questions posed as follows:

Questions 1 and 2 - Negative.

Question 3 - Affirmative.

Questions 4 and 5 - No necessity to answer.

[70] The appeals by the purchasers are consequently allowed and the appeals by the developer are dismissed. As agreed by the parties, there will be no order as to costs.

[71] This judgment is prepared pursuant to s 78(1) of the Courts of Judicature Act 1964, as Justice Alizatul Khair binti Osman Khairuddin has since retired.